Abstract

Fetal growth restriction (FGR), a clinically significant pregnancy disorder, is poorly understood at the molecular level. This study investigates idiopathic FGR associated with placental insufficiency. Previously, we showed that the homeobox gene HLX is expressed in placental trophoblast cells and that HLX expression is significantly decreased in human idiopathic FGR. Here, we used the novel approach of identifying downstream targets of HLX in cell culture to detect potentially important genes involved in idiopathic FGR. Downstream targets were revealed by decreasing HLX expression in cultured trophoblast cells with HLX-specific small interfering RNAs to model human idiopathic FGR and comparing these levels with controls using a real-time PCR-based gene profiling system. Changes in candidate HLX target mRNA levels were verified in an independent trophoblast cell line, and candidate target gene expression was assessed in human idiopathic FGR-affected placentae (n = 25) compared with gestation-matched controls (n = 25). The downstream targets RB1 and MYC, cell cycle regulatory genes, showed significantly increased mRNA levels in FGR-affected tissues compared with gestation-matched controls, whereas CCNB1, ELK1, JUN, and CDKN1 showed significantly decreased mRNA levels (n = 25, P < 0.001, t-test). The changes for RB1 and CDKN1C were verified by Western blot analysis in FGR-affected placentae compared with gestation-matched controls (n = 6). We conclude that cell cycle regulatory genes RB1, MYC, CCNB1, ELK1, JUN, and CDKN1C, which control important trophoblast cell functions, are targets of HLX.

Fetal growth restriction (FGR), also known as intrauterine growth retardation, is a significant pregnancy disorder associated with major perinatal complications including stillbirth, prematurity, fetal compromise, infant morbidity and mortality. Moreover, later in life, FGR-affected individuals also have an increased risk of chronic disorders such as ischemic heart disease, maturity onset diabetes, and psychiatric disorders.1,2 A common definition of FGR is a birth weight at or below the 10th percentile for gestational age and gender, failure of the fetus to grow to its genetically determined potential size, and the likely presence of an underlying pathological process that inhibits the expression of the normal intrinsic growth potential. Obvious causes of FGR are fetal (eg, genetic defects), placental (eg, infarcts), and maternal factors (eg, maturity onset diabetes, certain autoantibody disorders, alcohol abuse, and smoking), but these factors account for only 30% of FGR cases. The remaining 70% of FGR cases with no obvious causes are classified as “idiopathic” and are commonly attributed to uteroplacental insufficiency.

Placental insufficiency is associated with abnormal trophoblast function in FGR. Villous outgrowth, which is determined by trophoblast proliferation, is reduced in the FGR-affected placenta together with increased apoptosis of these cells.3 Defective trophoblast function also results in growth restriction of the fetus due to the reduction in transfer of nutrients and growth factors to the fetus.4 Another significant defect in FGR is uteroplacental ischemia due to failure of the specialized extravillous trophoblast cells to proliferate, invade, and subsequently transform and remodel the maternal spiral arteries in the placental bed.5 Villous structural defects, vascular abnormalities, and reduced branching of the villous structure are also seen in FGR.6–8 These defects also prevent adequate nutrient transfer to the fetus.9

Mouse knockout studies of transcription factors provide genetic proof of the critical role of transcription factors in regulating placental development.10–14 Some knockout gene phenotypes show the hallmarks of major human placental disorders13 and thus may play an important role in the pathogenesis of human idiopathic FGR.

The homeobox gene family of transcription factors is extensively characterized in the human placenta and embryo.15,16 These genes are known to play important roles in implantation, placentation, and embryonic development in the mouse.11–13,17–20 Only a few studies of human homeobox genes have provided evidence that homeobox genes are important in human placental development and particularly in trophoblast development and differentiation.10,16,21,22 Targeted disruption of the Hlx homeobox gene in the mouse has shown that Hlx also plays a fundamental role in visceral organogenesis.23 Hlx mutant mice resulted in developing gut and liver diverticulum defects. In addition, Hlx mutation also showed a defect in proliferation and resulted in embryonic death due to liver failure.23

Our interest is in the homeobox gene HLX, the human homologue of mouse Hlx homeobox gene, which is highly expressed in hematopoietic progenitors and shows decreased expression levels in activated lymphocytes.24 HLX inactivation impairs CD34+ bone marrow cell proliferation in response to stimulation by cytokines while inducing differentiation of these cells. Moreover, HLX inactivation reduces the levels of c-myc, c-fos, cyclin B, and p34cdc2 mRNA expression,24 which are cell cycle regulator genes implicated in trophoblast cell function.25 Therefore, c-myc, c-fos, cyclin B, and p34cdc2 were the first identified targets of HLX.

Slavotinek et al26 have described HLX mutations in human congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients. In this study, the HLX gene was sequenced in 119 congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients, because HLX is in the deleted interval at ch1q41-1q42 for human congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and four amino acid substitution mutations (p.A235V, p.S12F, p.S18L, and p.D173Y) resulted in congenital diaphragmatic hernia phenotype.26 Slavotinek et al26 concluded that HLX mutations are etiologically important in human diaphragm formation by interaction with other genetic or environmental factors. Furthermore, Suttner et al27 have determined that HLX gene variants influence the development of childhood asthma. Their study identified 19 polymorphisms in the HLX gene, and two tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms representing seven polymorphisms were associated with childhood asthma in a study population of 3099 German children. Suttner et al27 concluded that genetic alterations in HLX contributed to the pathogenesis of childhood asthma.

Previously, we provided evidence that HLX is expressed primarily in the proliferating cytotrophoblast cell types in early placental development.28 Furthermore, we postulated that reduced levels of HLX are required for cytotrophoblast differentiation and that dysregulation of HLX expression contributed to the aberrant cytotrophoblast proliferation and differentiation associated with placental pathologies.28 Recently, we also provided evidence of HLX regulation by growth factors and cytokines and established that HLX is an important regulator for signal transduction-mediated proliferation of human trophoblast cells.29 By using four independent small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides, we have reported a significant 60 to 85% decrease in HLX mRNA and 73 to 87% decrease in protein expression by HLX siRNA transfection compared with the mock-transfected control trophoblast cells.29 Finally, we showed that HLX mRNA and protein expression is significantly decreased in human idiopathic FGR,30 suggesting that HLX expression may be of pathological significance.

The focus of this study is to identify downstream target genes of HLX in cultured trophoblast and to identify the molecular pathways that are affected in human idiopathic FGR.

Signal transduction pathways that regulate trophoblast functions include the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt, protein kinase A, protein kinase C, p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase, Jak-Stat, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.31–33 Of these, the two pathways that are frequently used by trophoblast cells are the Jak-Stat and MAPK pathways.33 The human MAPK signaling pathway PCR array was used in this study.

We hypothesize that placental HLX downstream target gene expression will be significantly altered in human idiopathic FGR pregnancies compared with uncomplicated pregnancies. In this study, an in vitro cell culture model using HLX siRNA, in trophoblast cells, was used. PCR array comparisons were made between HLX siRNA-treated cells and control cells transfected with a siRNA that does not target human genes. Candidate HLX target gene expression levels were then assessed by real-time PCR, using validated probes, in human idiopathic FGR-affected placentae compared with gestation age-matched control placentae.

Materials and Methods

Patient Details and Tissue Sampling

Human placentae from pregnancies complicated by idiopathic FGR (n = 25) and gestation-matched control pregnancies (n = 25) were obtained with informed patient consent and with approval from the Research and Ethics committees of The Royal Women's Hospital. These samples have been characterized and used in our previous gene expression studies.30,34 Ultrasound was used for the prospective identification of growth-restricted fetuses. The clinical characteristics of FGR-affected pregnancies and the gestation age-matched controls used in this study are as previously published by Murthi et al.30,34 As described,30,34 the inclusion criteria for this study were a birth weight less than the 10th percentile for gestation age using Australian growth charts35 and any two of the following criteria diagnosed on antenatal ultrasound: abnormal umbilical artery Doppler flow velocimetry, oligohydramnios as determined by amniotic fluid index <7 on antenatal ultrasound performed before delivery, or asymmetric growth of the fetus as quantified from the head circumference-to-abdominal circumference ratio (>1.2). Placental tissue subjected to maternal smoking, chemical dependency, multiple pregnancies, pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, prolonged rupture of the membranes, fetal congenital anomalies, or suspicion of intrauterine viral infection were excluded from this study. Pre-eclampsia cases with associated FGR were also excluded from this study. The last menstrual period dates were used to calculate the gestation age for both FGR and control patients and further confirmed by early pregnancy ultrasound. Control patients were selected to match FGR cases according to gestation. All control patients presented with either spontaneous labor or required elective delivery by induction of labor/cesarean section. Preterm control patients presented in spontaneous idiopathic preterm labor or underwent elective delivery for conditions not associated with placental dysfunction (eg, elective cesarean section due to maternal breast cancer). Particularly, control patients did not have clinical evidence of FGR, pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, prolonged rupture of the membranes, or ascending infection. All control patients gave birth to normally formed babies with birth weights appropriate for gestation. All control placentae obtained were grossly normal with no observed abnormalities such as infarcts.

Placental tissues were excised from randomly selected areas of central placental cotyledons, after dissecting away any attached decidua. Samples were processed within 10 minutes of delivery of the placenta. Samples of fresh placental tissues were divided into small pieces and thoroughly washed in 0.9% PBS to minimize blood contamination and then snap frozen and stored at −80°C for RNA analysis.

Cell Culture

Human trophoblast cell lines are a well established model for examining trophoblast function in vitro. In this study, two well-characterized, human extravillous trophoblast cell lines SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo were used, because these cell lines retain many features of normal extravillous trophoblast cells, including human placental lactogen, human chorionic gonadotropin, and HLA-Class1.36,37 The cell lines used in this study are long term, which senesce after ∼30 passages. For this work, SGHPL-4 cells (passages 5 to 12) were cultured in supplemented Ham's F-10 medium, and the HTR-8/Svneo cells (passages 16 to 19) were cultured in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium, as described previously.29

Inactivation of HLX by siRNA

Inactivation of HLX by siRNA was performed as previously described.29 Briefly, cultured trophoblast cells were grown in Ham's F-10 nutrient mixture/RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum for 48 hours (2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates) and then transfected with two individual HLX siRNAs [HLX-si1 sequence: r(UGAAUUUCUUGGGUUCGAG)d(TT); HLX-si2 sequence: r(AAACCUUUUCUCCAGG CCU)d(TT)], using RNAiFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Victoria, Australia). The mock-transfected control wells received all reagents, except the siRNA oligonucleotide. Cells were returned to incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Negative control siRNAs consisted of a pool of enzyme-generated siRNA oligonucleotides of 15 to 19 bp in length, which were not specific for any known human gene (catalog number 0652-13-7000, Superarray Bioscience, Frederick, MD) and showed no sequence similarity to HLX.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA from excised placental tissue was isolated as described previously by Murthi et al.30,34 Briefly, 300 mg of placental tissue was homogenized, and total RNA was isolated by acid guanidium isothiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction and lithium chloride precipitation according to the method of Chomzynski and Sacchi38 and as modified by Puissant and Houdebine.39 Total cellular RNA from cultured trophoblast cells was isolated using the QIAShredder and an RNeasy Microkit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand synthesis for real-time PCR cDNA preparation was performed on 2 μg of total RNA from placental tissue and cultured cells, using Superscript III ribonuclease H-reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Victoria, Australia). First-strand synthesis of cDNA for RT2-profiler PCR array was performed using the RT2 First Strand kit (catalog number c-03; SuperArray Bioscience). Briefly, 10 μl of reverse transcriptase mixture (containing reverse transcriptase buffer, primer, external control mix and reverse transcriptase enzyme mix) was added to 10 μl of genomic DNA elimination mixture (containing 1 μg of RNA, gDNA elimination buffer, and RNase-free water) and incubated at 42°C for 15 minutes. RNA degradation and reverse transcriptase inactivation were performed by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes.

PCR Array

The downstream target genes of HLX were determined using the real-time PCR based “RT2 profiler PCR array” for gene profiling (SuperArray Bioscience Corporation, catalog no. PHAS-061). The human MAPK signaling pathway PCR array was used in this study. This commercially available PCR array encompassed the gene expression profiles of 84 genes related to the MAPK signaling pathway, which is an important signaling pathway in the regulation of human trophoblast function.33 Members of the MAP kinase kinase kinase (MKKK), MAP kinase kinase (MKK), and MAPK families are represented on this array as well as transcription factors and genes whose expression is induced by MAPK signaling. In addition, the array also included genes related to scaffolding and anchoring. Furthermore, the PCR array chosen in this study contained several cell cycle regulatory genes, including CCNB1, MYC, CDKN1C, and JUN, which have been previously identified to be the targets of HLX in hematopoietic progenitor cells.24

Procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, diluted cDNA prepared using the RT2 First-Strand kit (as described above) was added to a master mix containing the fluorescent SYBR green/ROX dye. Aliquots from this mix were added to a 96-well plate that contained 84 predispensed gene-specific primer sets. The plates (one for each HLX-siRNA and controls) were then placed in an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (PerkinElmer-Applied Biosystems, Victoria, Australia) for quantitation of gene expression under the following cycling parameters: 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and primer extension at 60°C for 1 minute. Each plate contained a panel of five housekeeping gene primers for normalization of the PCR array data, as well as estimation of the linear dynamic range of the assay. The housekeeping gene panel consisted of β2-micrglobulin (B2M), hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltansferase 1 (HPRT1), ribosomal protein L13a (RPL13A), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and β-actin (ACTB). Furthermore, for each reaction, both negative control (no reverse transcriptase enzyme added) and template control (no cDNA added) were included as controls. Raw data were acquired and processed with ABI Sequence Detector System software version 1.0 (PerkinElmer-Applied Biosystems) to calculate the threshold cycle (Ct) value. Relative gene expression values (fold change) were subsequently determined according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the fold change for each gene from the mock control array and the HLX-siRNA-treated array was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt, normalized to the average Ct value of the five housekeeping genes. Fold changes >1 were fold increase, and for fold changes <1, the negative inverse of the result was reported as a fold decrease. Candidate gene prioritization was based on the highest positive and lowest negative fold change differences.

Real-Time PCR

Verification of candidate HLX target gene mRNA expression (identified from PCR array) in mock control and HLX siRNA-transfected SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/Svneo cells was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 (PerkinElmer-Applied Biosystems) using prevalidated TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (RB1 Assay ID Hs00153108_m1, EGR1 Assay ID Hs00152928_m1, MYC Assay ID Hs00153408_m1, JUN Assay ID Hs00277190_s1, Cyclin B1 Assay ID Hs00259126_m1, ELK1 Assay ID Hs00428286_g1, and CDKN1C Assay ID Hs00175938_m1; Applied Biosystems). Gene expression quantitation was performed as the second step in a two-step RT-PCR protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 20 μl of PCR mix containing TaqMan Universal PCR master mix, TaqMan Gene Expression Assay mix and 3.5 ng of cDNA was used. Amplification was performed for 40 cycles, including denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 60 seconds. Gene expression for the housekeeping gene GAPDH was co-amplified with HLX in the same reaction well. Murthi et al34 from our laboratory previously showed that GAPDH is a suitable endogenous reference gene for relative gene expression studies in placental tissues from human idiopathic FGR, and its expression is not altered in FGR placentae compared with control placentae. The GAPDH primers (5′-GCACCACCAACTGCTTAGCA-3′ and 5′-GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGATG-3′) and TaqMan probe (5′-VIC-TCGTGGAAGGACTCATGACCACAGTCC-TAMRA-3′) were designed using Primer Express 1.5 software (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions for GAPDH were as per the HLX target genes. Relative quantitation of HLX target gene expression normalized to GAPDH was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen,40 using the mock control as a calibrator (ABI Prism 7700 Sequence detection system, User Bulletin number 2, 2001). These candidate HLX target genes were then further tested for expression in FGR-affected human placental samples compared with gestation age-matched controls, as per the protocol described above.

Western Immunoblotting

Samples were electrophoresed on a 10% PAGE/0.1% SDS gel in running buffer (250 mmol/L Tris and 1.92 mmol/L glycine) and transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 30 minutes in transfer buffer (255 mmol/L Tris, 1.92 mmol/L glycine, and 0.1% SDS). The filter was blocked with 10% (w/v) nonfat milk powder/TBS for 1 hour. Incubation with the RB1 (0.5 μg/ml), CDKN1C (1 μg/ml) (Sapphire Biosciences, New South Wales, Australia) or GAPDH (0.5 μg/ml) (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) antibodies was performed overnight at 4°C. The filter was then washed in Tris-buffered saline and incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (1.5 μg/ml) (Amersham Life Sciences, New South Wales, Australia) in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk powder/TBS for at least 1 hour at room temperature. Streptavidin-HRP (1.5 μg/ml) in 2% nonfat milk powder/Tris-buffered saline buffer was added and incubation was performed at room temperature for 1 hour. Tyramide signal amplification was then performed, according to the manufacturer's instructions (PerkinElmer), for CDKN1C blots. RB1 and GAPDH antibodies did not require tyramide signal amplification. Detection of protein bands was performed using ECL-Lumilyte autoradiography kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (PerkinElmer).

Data Analysis

All parameters for the gestation age-matched, FGR-affected pregnancies and controls were described as mean ± SEM. Differences between the clinical characteristics of the FGR-affected pregnancies and the control patients were investigated using either χ2 test or Student's t-test where appropriate. The difference in mRNA expression of the HLX target genes between siRNA-treated and control-cultured trophoblast cells and between FGR-affected and control pregnancies was assessed by t-test. A value of P < 0.001 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of HLX Downstream Targets

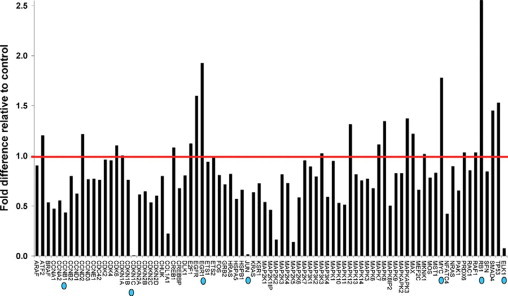

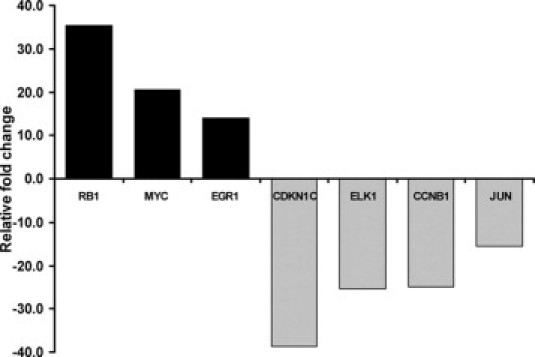

The SGHPL-4 human trophoblast cell line was transfected with two independent siRNA oligonucleotides designed to target different regions of the HLX cDNA as described in Materials and Methods. HLX-si3 and HLX-si4 were chosen for this study, because they resulted in a maximal decrease of HLX expression in both SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo cell lines from our previous experiments.29 The HLX gene was inactivated at the mRNA and protein levels, in cultured trophoblast cells as described previously.29 PCR array for identification of potential HLX downstream targets was performed using the human MAPK pathway specific array. Gene expression (fold change) was calculated relative to five different housekeeping genes included in the array. The relative mRNA expression of the 84 predispensed genes following siRNA-mediated reduction of HLX expression is shown in Figure 1. Of the 84 genes in the array, genes that showed significantly altered mRNA levels with HLX inactivation using two individual HLX siRNAs were prioritized as candidate downstream targets of HLX. As shown in Figure 2, retinoblastoma-1 (RB1), myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (MYC), and early growth response-1 (EGR-1) mRNA levels were highly increased with positive fold changes of 35.41, 20.57, and 13.98, respectively. On the other hand, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor-1C (CDKN1C), ELK1 (a member of the ETS oncogene family), cyclin B1 (CCNB1), and JUN oncogene mRNA levels were substantially decreased as a result of HLX gene reduction, with negative fold changes of 38.7, 25.29, 24.98, and 15.55 respectively.

Figure 1.

Identification of HLX downstream target genes. RNA was extracted from SGHPL-4 cells transfected with HLX siRNA, transcribed into first strand cDNA, and the RT2 profiler PCR array was performed for gene profiling. Following initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, the 84 predispensed genes and a panel of housekeeping genes were amplified for 40 cycles including denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and primer extension at 60°C for 1 minute. Relative gene expression values (fold change above or below threshold value of 1) were subsequently calculated for the HLX siRNA-treated plate, relative to the mock control plate, normalized to the housekeeping gene panel. The red line shows the threshold value at 1. The prioritized candidate HLX target genes are indicated by blue dots.

Figure 2.

Prioritized HLX downstream target genes. HLX downstream target genes, as identified in Figure 1, were prioritized on the basis of most increased and most decreased gene expression with HLX siRNA transfection, compared with the control. Fold changes greater than 1 were reported as fold increase, and for fold changes <1, the negative inverse of the result was reported as a fold decrease.

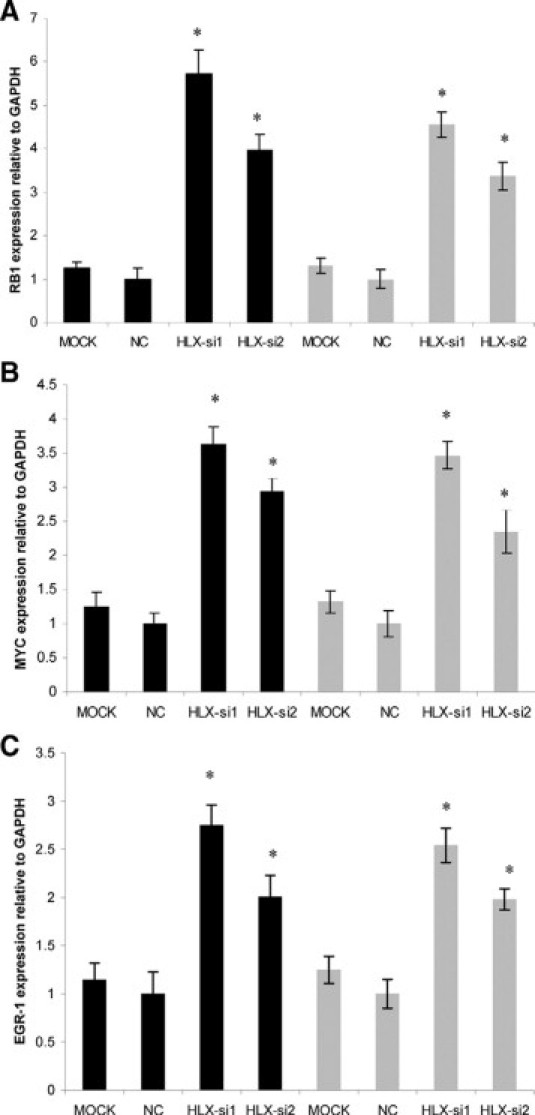

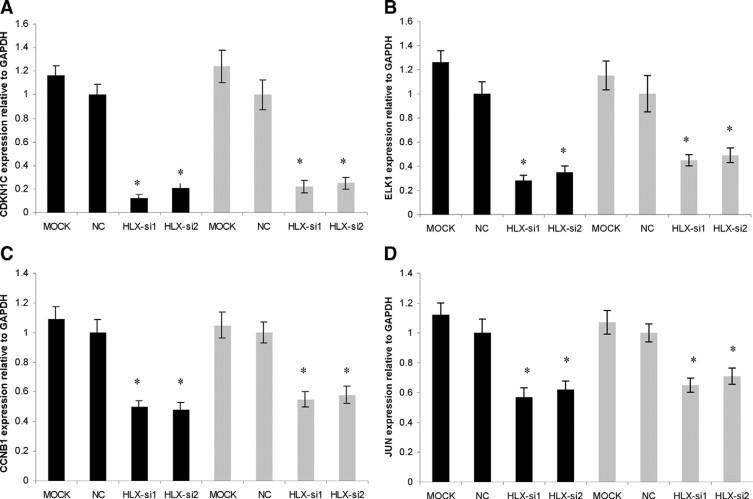

Validation of Prioritized HLX Target Genes in Independent Trophoblast Cell Lines

The prioritised HLX downstream target genes identified from PCR-array were further validated by individual real-time PCR using independent gene-specific PCR primers (validated Taqman Assays), in both trophoblast cell lines SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo, using the two siRNA oligonucleotides HLX-si3 and HLX-si4. The independent validation results were consistent with the PCR-array. RB1, MYC, and EGR-1 mRNA levels were significantly increased (n = 3, P < 0.001, t-test) (Figure 3), whereas CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN mRNA levels were significantly decreased (n = 3, P < 0.001, t-test) with HLX inactivation using HLX-si3 and HLX-si4, in both the cell lines tested (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Validation of target genes that showed increased expression following siRNA-mediated HLX silencing. cDNA (3.5 ng) from SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo cells transfected with HLX-siRNA and the mock control were amplified for 40 cycles including denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 60 seconds (using prevalidated Taqman gene expression assays from Applied Biosystems). Gene expression quantitation for the housekeeping gene GAPDH was coamplified with each HLX target gene. Relative quantification of RB1, MYC. and EGR1 (A, B, and C, respectively) expression in SGHPL-4 and HTR-8 cells normalized to GAPDH was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen,40 using the mock control as a calibrator. Significance at *P < 0.001 (n = 3, t-test). The black and gray bars represent the SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo cell lines, respectively.

Figure 4.

Validation of target genes that showed decreased expression following siRNA-mediated HLX silencing. Relative quantification of CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN (A–D) expression in SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo cells normalized to GAPDH was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen,40 using the mock control as a calibrator. Significance at *P < 0.001 (n = 3, t-test). The black and gray bars represent the SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo cell lines, respectively.

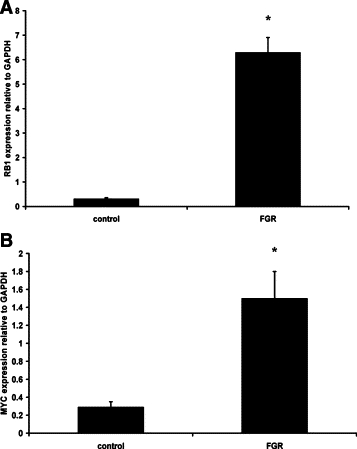

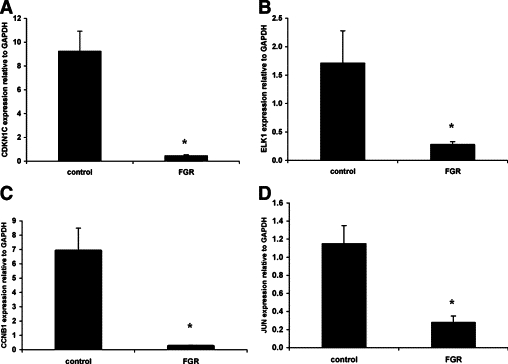

mRNA Expression of HLX Target Genes in Human Idiopathic FGR

Expression of the HLX downstream target genes identified in cultured trophoblast cells were tested in FGR-affected placentae compared with gestation age-matched control placentae. As shown in Figure 5, RB1 and MYC mRNA levels were significantly increased (n = 25, P < 0.001, t-test) whereas CCNB1, ELK1, JUN, and CDKN1C mRNA levels were significantly decreased (n = 25, P < 0.001, t-test) (Figure 6). However, the mRNA level of EGR-1 was unchanged in FGR-affected placentae compared with controls (4.8 ± 0.77 control versus 4.55 ± 0.93 FGR, n = 25, P = 0.83, t-test).

Figure 5.

Increased HLX target gene expression in FGR-affected placentae. Real-time PCR for relative quantitation of RB1 (A) and MYC (B) normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH were performed in all gestation-matched controls (n = 25) and FGR-affected placentae (n = 25). Data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen.40 Statistical comparisons were performed using t-test. Significance at *P < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Decreased HLX target gene expression in FGR-affected placentae. Relative quantitation of CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN (A–D) normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH were performed in all controls (n = 25) and FGR-affected placentae (n = 25). Real-time PCR data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen.40 Statistical comparisons were performed using t-test. Significance at *P < 0.001.

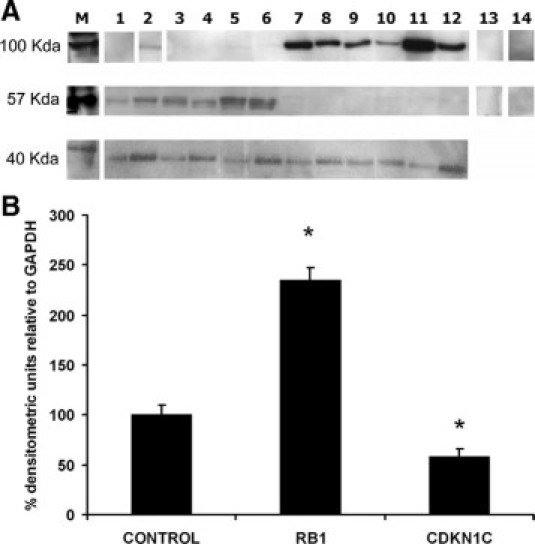

Protein Expression of RB1 and CDKN1C in Human Idiopathic FGR

The expression of RB1 and CDKN1C, which showed the highest increase and decrease in mRNA levels, respectively, in FGR-affected placental tissues, was further assessed at the protein level. As shown in Figure 7, RB1 protein expression was significantly increased in FGR-affected placentae (n = 6, P < 0.001, t-test) (Figure 7A), whereas CDKN1C protein expression was significantly decreased in FGR-affected placentae compared with gestation-matched controls, relative to the housekeeping gene GAPDH (n = 6, P < 0.001, t-test), which was consistently expressed in all samples used (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

HLX target protein expression in FGR-affected placentae. Following protein extraction of human idiopathic FGR-affected placentae (n = 6) and control placentae (n = 6), protein assays were performed. Protein samples (25 μg) were then electrophoresed and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was performed using commercially available RB1, CDKN1C, and GAPDH rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Composite images of autoradiographic detection of RB1 (100 kDa), CDKN1C (57 kDa), and GAPDH (40 kDa) are shown in A. Lanes 1–6 are control placentae, whereas lanes 7–12 are FGR-affected placental samples. Lanes 13 and 14 are the primary antibody omitted and rabbit serum negative controls, respectively. B: The densitometric quantitation of RB1 and CDKN1C in A, as the percentage densitometric values relative to GAPDH. Significance at *P < 0.001, n = 6, t-test. Where indicated by white dividing lines, lanes 1 and 2 are from different areas of the same blot, whereas lanes 13 and 14 are from independent blots.

Discussion

Homeobox genes control transcription by binding to the regulatory elements in the promoter regions of their target genes. These downstream targets of homeobox genes often perform specialized roles in controlling various cell functions. Therefore, homeobox target genes are referred to as genes that act downstream of the homeobox, which may be involved, directly or indirectly, in the mediation of homeobox gene function.

In this study, a well-defined group of human pregnancies with severe idiopathic FGR, which is frequently associated with uteroplacental insufficiency, were used. These samples have been used in gene expression studies from this laboratory.30,34 The pregnancies complicated by FGR are at risk due to poor placental function41 and are characterized by asymmetric growth of the fetus, altered umbilical artery diastolic velocities, and reduced liquor volume.6,42 Typically, the placentae are smaller than controls and have a variety of morphological and functional defects. Hence, in this study, the expression levels of HLX target genes were determined in placental samples that meet the clinical selection criteria for FGR.30

Previous studies have shown that reduced trophoblast proliferation41 and increased apoptosis43 occur in the villous core of FGR-affected placentae, whereas decreased trophoblast invasion44 and migration45 are seen in the FGR placental bed. We have previously shown that siRNA-mediated HLX inactivation significantly decreases trophoblast proliferation in the SGHPL-4 and HTR8-SV/neo cell lines by up to 80%, compared with mock-transfected cells, and that HLX is a mediator of the cytokine colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent trophoblast proliferation.29 We have also shown that trophoblast migration significantly decreases by 70% with HLX-siRNA transfection and that HLX is a mediator of hepatocyte growth factor-dependent trophoblast migration, but siRNA-mediated HLX inactivation does not affect trophoblast invasion (our unpublished data). Therefore, a functional correlation between HLX and trophoblast function is evident and the placental samples used in this study reflect the functional activity of HLX in the human placenta (ie, trophoblast proliferation and migration).

A key pathway in trophoblast function is the MAPK pathway.33 This study has shown that reduced HLX expression in cultured trophoblast cells significantly alters genes in the MAPK pathway. Therefore, HLX may play an important role in directly signaling trophoblast function via the MAPK pathway, which consists of several tumor suppressor genes and cell cycle regulators.

In this study, we have identified cell cycle regulatory genes as downstream targets of the homeobox gene HLX in cultured trophoblast cells, namely RB1, MYC, EGR1, CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN. RB1 and MYC mRNA expression was increased with HLX inactivation, whereas EGR1, CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN mRNA expression was decreased compared with mock-transfected control cells. These findings are not only consistent in two independent trophoblast cell lines, SGHPL-4 and HTR-8/SVneo, but also reflected in FGR-affected human placental tissue that is associated with abnormal trophoblast function. RB1 and MYC mRNA expression was significantly increased in idiopathic FGR placentae, whereas CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN expression was significantly decreased. Although a significant increase in EGR-1 mRNA expression in HLX-inactivated cultured trophoblast cells was observed, EGR-1 expression was not significantly altered in idiopathic FGR placental tissue compared with control placentae. This difference in EGR-1 expression between cultured trophoblast cells and human placental tissue suggests that multiple cell types present in the whole placenta may regulate EGR-1 expression.

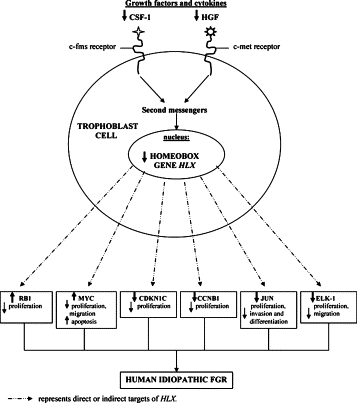

Various studies have shown that RB1, MYC, EGR1, CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN are expressed in human extravillous trophoblast cells and are implicated in the regulation of cell proliferation and migration.46–52 This is consistent with our finding of HLX expression in the human placenta in actively proliferating and migrating trophoblast cells.28 Results from this study suggest that RB1, MYC, EGR1, CDKN1C, ELK1, CCNB1, and JUN are direct or indirect targets of homeobox gene HLX and that HLX-mediated target gene expression in trophoblast cells may cause the reduction in trophoblast proliferation and in migration associated with idiopathic FGR. The gene expression changes of HLX downstream targets in trophoblast cells, and their interrelationship with human idiopathic FGR is summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram: Summary of HLX downstream target gene expression changes that alter trophoblast cell functions associated with human idiopathic FGR.

Mouse knockout studies for HLX target genes identified in this study provide evidence that HLX target gene mutations directly result in an FGR-like phenotype due to placental defects. Targeted disruption of c-myc gene (homolog of MYC) in the mouse model system results in severe placental defects and embryonic death due to placental insufficiency.53

The product of the RB1 gene is a nuclear phosphoprotein that may act as an inhibitor of cell proliferation.54 Wu et al55 have demonstrated that reduction of RB1 gene expression in the mouse model system results in excessive proliferation of trophoblast cells and a severe disruption of the normal labyrinth architecture in the placenta. This is accompanied by a decrease in vascularization and a reduction in placental transport function and ultimately embryonic death.55 In our results, RB1 showed the highest increase in mRNA levels in FGR-affected placentae compared with control placentae, and this was shown to be reflected in increased protein levels. Therefore, increased RB1 expression levels in FGR may reduce trophoblast proliferation and result in a fewer number of trophoblast cells available to migrate and invade into the maternal decidua. This reduction in trophoblast proliferation may lead to the shallow, inadequate remodeling of the maternal spiral arteries associated with FGR.

Studies have shown that targeted disruption of CDKN1C in the mouse model system results in severe placental defects.56 CDKN1C knockout mice have displayed an array of pre-eclampsia-like symptoms, including placental abnormalities, hypertension, proteinuria, and premature labor.56 CDKN1C is a maternally imprinted gene that is important in the regulation of embryonic implantation and development, placental growth, and the pathogenesis of proliferative trophoblastic diseases.48 This is consistent with our data, suggesting that HLX-mediated reduction of CDKN1C expression may reduce trophoblast proliferation. Because CDKN1C was the most decreased gene in FGR out of the prioritized HLX target genes, its expression was also confirmed at the protein level. These results show that CDKN1C protein expression is also significantly decreased in idiopathic human FGR placentae compared with controls. Therefore, the reduced levels of HLX may directly or indirectly cause the reduction in CDKN1C mRNA and protein expression seen in idiopathic FGR.

Most importantly, the four HLX downstream target genes CCNB1, MYC, CDKN1C, and JUN, previously identified as HLX target genes in hematopoietic progenitor cells,24 were confirmed as HLX targets in cultured trophoblast cells in this study. Therefore, this study has demonstrated that the HLX homeobox gene targets cell cycle regulatory genes in two independent cell types, and these targets are significantly altered in human idiopathic FGR placentae compared with gestation age-matched controls.

In conclusion, this is the first study to identify downstream targets of a homeobox gene in the human placenta. This study shows that candidate downstream target genes of the homeobox gene HLX are significantly altered in human idiopathic FGR-affected placentae, compared with gestation-matched control placentae from uncomplicated pregnancies. Most importantly, the findings of this study demonstrate that in vitro models for siRNA-mediated knockdown of HLX expression in cultured trophoblast cells show consistent changes to those observed in human idiopathic FGR where HLX levels are reduced. These results suggest that reduced levels of HLX seen in FGR cause direct or indirect effects on target genes that have been shown to be altered in FGR. Therefore, reduced HLX levels directly or indirectly cause gene expression changes in targets that have deleterious effects on trophoblast function.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Clinical Research Midwife Ms. Susan Nisbet for the collection of placental tissues and Dr. Joanne Said for the characterization of clinical samples used in this study.

Footnotes

Supported by National Health and Medical Research Council project grant 509140. The authors would also like to thank Lynne Quayle Charitable Trust Fund (Equity Trustees) and the Marian E.H. Flack Trust for funding support for this project and also the University of Melbourne for the award of an Early Career Researcher Grant (to P.M.) G.R was awarded the Felix Meyer Postgraduate Scholarship from the University of Melbourne and the Royal Women's Hospital Postgraduate Scholarship.

References

- 1.Rosso IM, Cannon TD, Huttunen T, Huttunen MO, Lonnqvist J, Gasperoni TL. Obstetric risk factors for early-onset schizophrenia in a Finnish birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:801–807. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gale CR, Martyn CN. Birth weight and later risk of depression in a national birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axt R, Kordina AC, Meyberg R, Reitnauer K, Mink D, Schmidt W. Immunohistochemical evaluation of apoptosis in placentae from normal and intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1999;26:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regnault TR, Marconi A, Smith C, Glazier J, Novak D, Sibley C, Jansson T. Placental amino acid transport systems and fetal growth restriction—a workshop report. Placenta. 2006;26(Suppl A):S76–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and pre-eclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingdom J, Huppertz B, Seaward G, Kaufmann P. Development of the placental villous tree and its consequences for fetal growth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaddha V, Viero S, Huppertz B, Kingdom J. Developmental biology of the placenta and the origins of placental insufficiency. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;9:357–369. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arroyo JA, Winn VD. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in the IUGR placenta. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:172–177. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed A, Perkins J. Angiogenesis and intrauterine growth restriction. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14:981–998. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knoefler M, Kalionis B, Huelseweh B, Bilban M, Morrish DW. Novel genes and transcription factors in placental development—a workshop report. Placenta. 2000;21(Suppl A):S71–S73. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemberger M, Cross JC. Genes governing placental development. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossant J, Cross JC. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:538–548. doi: 10.1038/35080570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapin V, Blanchon L, Serre AF, Lemery D, Dastugue B, Ward SJ. Use of transgenic mice model for understanding the placentation: towards clinical applications in human obstetrical pathologies? Transgenic Res. 2001;10:377–398. doi: 10.1023/a:1012085713898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross JC, Baczyk D, Dobric N, Hemberger M, Hughes M, Simmons DG, Yamamoto H, Kingdom JC. Genes, development and evolution of the placenta. Placenta. 2003;24:123–130. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn LM, Johnson BV, Nicholl J, Sutherland GR, Kalionis B. Isolation and identification of homeobox genes from the human placenta including a novel member of the Distal-less family, DLX4. Gene. 1997;187:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murthi P, So M, Gude NM, Doherty VL, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeobox genes are differentially expressed in macrovascular human umbilical vein endothelial cells and microvascular placental endothelial cells. Placenta. 2007;28:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maas R, Bei M. The genetic control of early tooth development. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:4–39. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080010101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus P, Lufkin T. Mammalian Dlx homeobox gene control of craniofacial and inner ear morphogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 1999;Suppl 32–33:133–140. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1999)75:32+<133::aid-jcb16>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rinkenberger JL, Cross JC, Werb Z. Molecular genetics of implantation in the mouse. Dev Genet. 1997;21:6–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)21:1<6::AID-DVG2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons DG, Cross JC. Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2005;284:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn LM, Latham SE, Kalionis B. The homeobox genes MSX2 and MOX2 are candidates for regulating epithelial-mesenchymal cell interactions in the human placenta. Placenta. 2000;21(Suppl A):S50–S54. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murthi P, Hiden U, Rajaraman G, Liu H, Borg AJ, Coombes FJ, Desoye G, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Novel homeobox genes are differentially expressed in placental microvascular endothelial cells compared with macrovascular cells. Placenta. 2008;29:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hentsch B, Lyons I, Li R, Hartley L, Lints TJ, Adams JM, Harvey RP. Hlx homeobox gene is essential for an inductive tissue interaction that drives expansion of embryonic liver and gut. Genes Dev. 1996;10:70–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kehrl JH, Deguchi Y. Potential roles for two human homeodomain containing proteins in the proliferation and differentiation of human hematopoietic progenitors. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;10:173–176. doi: 10.3109/10428199309145879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrish DW, Dakour J, Li H. Life and death in the placenta: new peptides and genes regulating human syncytiotrophoblast and extravillous cytotrophoblast lineage formation and renewal. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2001;2:245–259. doi: 10.2174/1389203013381116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slavotinek AM, Moshrefi A, Lopez Jiminez N, Chao R, Mendell A, Shaw GM, Pennacchio LA, Bates MD. Sequence variants in the HLX gene at chromosome 1q41-1q42 in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Genet. 2009;75:429–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suttner K, Ruoss I, Rosenstiel P, Depner M, Pinto LA, Schedel M, Adamski J, Illig T, Schreiber S, Von Mutius E, Kabesch M. HLX1 gene variants influence the development of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajaraman G, Murthi P, Quinn L, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeodomain protein HLX is expressed primarily in cytotrophoblast cell types in the early human placenta. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2008;20:357–367. doi: 10.1071/rd07159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajaraman G, Murthi P, Leo B, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeobox gene HLX1 is a regulator of colony stimulating factor-1 dependent cell proliferation. Placenta. 2007;28:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murthi P, Doherty V, Said J, Donath S, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeobox gene HLX1 expression is decreased in idiopathic human fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:511–518. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaMarca HL, Dash PR, Vishnuthevan K, Harvey E, Sullivan DE, Morris CA, Whitley GS. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated extravillous cytotrophoblast motility is mediated by the activation of PI3-K, Akt and both p38 and p42/44 mitogen activiated protein kinases. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1733–1741. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knerr I, Schubert SW, Wich C, Amann K, Aigner T, Vogler T, Jung R, Dotsch J, Rascher W, Hashemolhosseini S. Stimulation of GCMa and syncytin via cAMP mediated PKA signaling in human trophoblastic cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3991–3998. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzgerald JS, Busch S, Wengenmayer T, Foerster K, de la Motte T, Poehlmann TG, Markert UR. Signal transduction in trophoblast invasion. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;88:181–199. doi: 10.1159/000087834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murthi P, Fitzpatrick E, Borg AJ, Donath S, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. GAPDH, 18S rRNA and YWHAZ are suitable endogenous reference genes for relative gene expression studies in placental tissues from human idiopathic fetal growth restriction. Placenta. 2008;29:798–801. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauran RL, Wein P, Sheedy M, Walstab J, Beischer NA. Update of growth percentiles for infants born in an Australian population. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;34:39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1994.tb01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choy MY, Manyonda IT. The phagocytic activity of human first trimester extravillous trophoblast cells. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2941–2949. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.10.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiverick KT, King A, Frank H, Cartwright JE, Schneider H. Cell culture models of human trophoblast II: trophoblast cell lines a workshop report. Placenta. 2001;22(Suppl A):S104–S106. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chomzynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puissant C, Houdebine LM. An improvement of the single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Biotechniques. 1990;8:148–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔC(T) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen CP, Bajoria R, Aplin JD. Decreased vascularization and cell proliferation in placentas of intrauterine growth-restricted fetuses with abnormal umbilical artery flow velocity waveforms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:764–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson MR, Walsh AJ, Morrow RJ, Mullen JB, Lye SJ, Ritchie JW. Reduced placental villous tree elaboration in small-for-gestation age pregnancies: relationship with umbilical artery doppler waveforms. J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 Pt 1):518–525. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huppertz B, Kadyrov M, Kingdom JC. Apoptosis and its role in the trophoblast. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;(69) 1:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burrows TD, King A, Loke YW. Trophoblast migration during human placental implantation. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2:307–321. doi: 10.1093/humupd/2.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quenby S, Brazeau C, Drakeley A, Lewis-Jones DI, Vince G. Oncogene and tumour suppressor gene products during trophoblast differentiation in the first trimester. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:477–481. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roncalli M, Bulfamante G, Viale G, Springall DR, Alfano R, Comi A, Maggioni M, Polak JM, Coggi G. c-Myc and tumour suppressor gene product expression in developing and term human trophoblast. Placenta. 1994;15:399–409. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chilosi M, Piazzola E, Lestani M, Benedetti A, Guasparri I, Granchelli G, Aldovini D, Leonardi E, Pizzolo G, Doglioni C, Menestrina F, Mariuzzi GM. Differential expression of p57kip2, a maternally imprinted cdk inhibitor, in normal human placenta and gestational trophoblastic disease. Lab Invest. 1998;78:269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kauma S, Hayes N, Weatherford S. The differential expression of hepatocyte growth factor and met in human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:949–954. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.3.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korgun ET, Celik-Oxenci C, Acar N, Cayli S, Desoye G, Demir R. Location of cell cycle regulators cyclin B1, cyclin A, PCNA, Ki67 and cell cycle inhibitors p21, p27 and p57 in human first trimester placenta and deciduas Histochem. Cell Biol. 2006;125:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bamberger AM, Bamberger CM, Aupers S, Milde-Langosch K, Loning T, Makrigiannakis A. Expression pattern of the activating protein-1 family of transcription factors in the human placenta. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:223–228. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takai N, Ueda T, Narahara H, Miyakawa I. Expression of c-Ets1 protein in normal human placenta. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:15–20. doi: 10.1159/000087855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubois NC, Adolphe C, Ehninger A, Wang RA, Robertson EJ, Trumpp A. Placental rescue reveals a sole requirement for c-Myc in embryonic erythroblast survival and hematopoietic stem cell function. Development. 2008;135:2455–2465. doi: 10.1242/dev.022707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeanblanc M, Mousli M, Hopfner R, Bathami K, Martinet N, Abbady AQ, Siffert JC, Mathieu E, Muller CD, Bronner C. The retinoblastoma gene and its product are targeted by ICBP90: a key mechanism in the G1/S transition during the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2005;24:7337–7345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu L, de Bruin A, Saavedra HI, Starovic M, Trimboli A, Yang Y, Opavska J, Wilson P, Thompson JC, Ostrowski MC, Rosol TJ, Woollett LA, Weinstein M, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. Extra-embryonic function of Rb is essential for embryonic development and viability. Nature. 2003;421:942–947. doi: 10.1038/nature01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knox KS, Baker JC. Genome-wide expression profiling of placentas in the p57Kip2 model of pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:251–263. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]