Abstract

Odontogenic tumors originate from the remains of migrating enamel epithelium after the completion of normal tooth genesis. These enamel epithelium remnants exhibit the ability to recapitulate the events that occur during tooth formation. Several lines of evidence suggest that aberrance in the signaling pathways similar to the ones that are used during tooth development, including the WNT pathway, might be the cause of odontogenic tumorigenesis and maintenance. In this study we demonstrated that WNT5A expression was intense in both the epithelial component of ameloblastomas, the most common epithelial odontogenic tumor, and in this tumor's likely precursor cell, the enamel epithelium located at the cervical loop of normal developing human tooth buds. Additionally, when WNT5A was overexpressed in enamel epithelium cells (LS-8), the clones expressing high levels of WNT5A (S) exhibited characteristics of tumorigenic cells, including growth factor independence, loss of anchorage dependence, loss of contact inhibition, and tumor formation in immunocompromised mice. Moreover, overexpression of WNT5A drastically increased LS-8 cell migration and actin reorganization when compared with controls. Suppression of endogenous WNT5A in LS-8 cells (AS) greatly impaired their migration and AS cells failed to form significant actin reorganization and membrane protrusion was rarely seen. Taken together, our data indicate that WNT5A signaling is important in modulating tumorigenic behaviors of enamel epithelium cells in ameloblastomas.

Odontogenic tumors comprise a group of lesions in the oral and maxillofacial region, ranging from benign to malignant neoplastic tissue. Similar to normal odontogenesis, odontogenic tumors exhibit characteristics of epithelium-mesenchyme interactions that occur during tooth genesis. After the formation of the tooth crown, enamel epithelium cells at the cervical loop directionally proliferate to the root area. After tooth formation is completed, these enamel epithelium cells are left in the periodontal ligament space and are believed to give rise to several epithelial odontogenic tumors.1,2 According to the World Health Organization in 2005, odontogenic tumors are classified in relation to their tissues of origin into epithelial, epithelial-ectomesenchymal, and ectomesenchymal neoplasms.3

Ameloblastoma, a usually benign but locally invasive tumor, is the most common odontogenic tumor derived from odontogenic epithelium. It is slow growing but has persistent growth that produces marked deformity of the face. The term “ameloblastoma” is derived from the histology of the tumor that resembles the developing enamel organ of the tooth germ.4,5 Ameloblastoma has a high recurrence rate (50 to 90%); therefore, wide surgical resection is the preferred treatment. The molecular determinants driving initiation and maintenance of ameloblastoma remain unclear. Evidence suggests that alteration in signaling pathways that are important for normal tooth development such as tumor necrosis factor, fibroblast growth factor, Sonic Hedgehog, and wingless-type (WNT) pathways could contribute to the etiology of ameloblastoma.6–9

WNT5A (wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A) belongs to the WNT family that controls several processes during embryogenesis including cell fate specification, tissue patterning, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and cell migration.10 While WNT5A also is implicated to play an important role in a variety of cancers, the function of WNT5A in tumorigenesis is obscure and contradictory.11 Evidence suggests that WNT5A possesses oncogenic properties and that WNT5A enhances the aggressive and malignant behaviors of cells in malignant melanoma,12 gastric cancer, lung cancer,13 and prostate cancer.14,15 On the other hand, WNT5A has been considered a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and primary dukes B colon cancer.16–18 In the case of odontogenic tumors, WNT5A expression in ameloblastoma has been reported,19 but its biological consequence has not been explored.

In the present study, we demonstrate strong WNT5A expression in the epithelial compartment of human ameloblastomas and in the enamel epithelium cells at the cervical loop during normal human tooth development. Furthermore, when overexpressed in enamel epithelium cells, LS-8, WNT5A promotes cell survival, instilling a loss of contact inhibition, loss of anchorage dependence, and increased tumor formation rate in nude mice. Overexpression of WNT5A also enhances cell migration, increases actin reorganization and filopodia/lamellipodia formation in LS-8 cells. Our results demonstrate that WNT5A overexpression has multiple effects on enamel epithelium cell behaviors that are all important characteristics of tumorigenic cells.

Materials and Methods

Samples Collection

Human tissue samples were obtained according to the institutional review board approved protocols. First occurrence, multicystic/solid ameloblastomas, were collected through the Oral Pathology Service at the University of North Carolina from 1998 to present. Tumors were obtained along with the patients’ clinicopathological and demographic data. Human primary tooth germs from 10th- to 19 6/7th-week-old fetus were obtained from patients undergoing abortion through the University of North Carolina Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Any fetuses with known genetic anomalies or medical conditions were excluded. All tissue samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and used for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Goat anti-mouse WNT5A polyclonal antibody (1:200) and recombinant mouse WNT5A were obtained from R and D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Specificity and the sensitivity of anti-WNT5A antibody were tested on mouse small intestine, hair follicles, and liver paraffin-embedded sections. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4-μm thick, paraffin-embedded sample sections by using the Elite Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Deparaffinized sections were blocked with normal serum and then incubated with anti-WNT5A antibody (1:200) at 4°C overnight. A biotinylated rabbit anti-goat antibody was used as the secondary antibody, and immunoreaction was visualized by using the 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine substrate kit for peroxidase (Vector Laboratories). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and evaluated for immunoreactivity.

Cell Culture

Mouse enamel epithelium cells established by immortalizing primary cultures of new born mouse enamel epithelium with Simian virus 40 large T antigen, LS-8 (generously provided by Dr. Malcolm Snead, University of Southern California), were cultured as previously described.20 Briefly, the cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco). Culture medium was replaced twice weekly.

Isolation of Wnt5a cDNA and Constructs Generation

Total RNA was isolated from mouse kidney by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Two micrograms of total RNA was used for reverse transcription (RT) and the cDNA was synthesized by using the Superscript RT kit (Invitrogen) followed by PCR with primers specific for full-length mouse Wnt5a. Primer sequences were as follows: 5′-CACCATGAAGAAGCCCATTGG-3′ and 5′-TTTGCACACGAACTGATC C-3′. The PCR products were verified and confirmed the expected size at 1140 bp. The Wnt5a-PCR products were then ligated into pcDNA3.1 V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) by using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The molecular weight of the ligated insert was analyzed by restriction enzymes HindIII and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Plasmids were then analyzed by sequencing at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, DNA sequencing facility.

Transfection and Stable Clone Establishment

The sense, antisense constructs (pcDNA3.1/Wnt5a and pcDNA3.1/ASWnt5a) or pcDNA 3.1/V5-HisA vector (empty vector [EV]) (Invitrogen), were transfected into LS-8 cell by using Fugene 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). After 48 hours, cells were trypsinized and plated at a low density. Cells were maintained and selected in the presence of Geniticin (600 μg/ml) (G418, Invitrogen) for up to 3 to 4 weeks. Single-cell derived stable clones were prepared by cloning rings and the expression of WNT5A from each clone was analyzed by Western blot.

Triton X-114 Phase Separation and Western Blot Analysis

To ensure the WNT5A secretion from stable clones, separation of Wnt5a in conditioned medium was performed according to the protocol for WNT3A separation with modification.21 In brief, conditioned medium collected from stable clones was mixed 1:1 with ice cold 4.5% Triton X-114, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, incubated on ice for 5 minutes, then at 31°C for 5 minutes, and centrifuged at 2000 × g at 31°C for 5 minutes. Equal volumes of detergent and aqueous phases of Triton X-114 were then evaluated for the presence of WNT5A by using Western blot.

Since the majority of secreted WNT5A was bound to the proteoglycans component of extracellular matrices,22 WNT5A bound to extracellular matrices and cell surface were collected, normalized against β-actin, and used to compare the level of WNT5A expression. Cells were washed twice with PBS and gently lysed in lysis buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1% TritonX-100) containing the P1860 protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich). The supernatant was collected for analysis. Equal volumes of each sample for Western blot were dissolved in SDS sample buffer in the presence of 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen), and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Biorad, Hercules, CA). WNT5A protein was detected by anti-WNT5A antibody (R and D Systems) (1 μg/ml), and the anti-goat conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used as a secondary antibody. β-actin was detected by anti- β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and the secondary antibody, anti-rabbit conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling). The immunoreactivity was visualized by using the ECL Plus kit (GE Health care, Piscataway, NJ).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from wild-type LS-8, EV clones, LS-8 clones derived overexpressing higher (S) and lower (AS) levels of Wnt5a by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Two micrograms of total RNA was used for RT by using the SuperArray Reaction Ready First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (SA Bioscience, Frederick, MD) containing random primers following the instructions provided in the user's manual. Real-time PCR was performed by using the RT2 SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (SA Bioscience) and sequence specific primers (SA Bioscience). The primers used were as follows: Wnt5a (number Mm.287544) and Gapdh (number Mm.343110). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by using the following cycling parameters: 10 minutes at 95°C; 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C; and 1 minute at 60°C. Dissociation curve analyses were performed by using the instrument's default setting immediately after each PCR run.

Cell Proliferation Assay

LS-8, EV, S, and AS clones were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cell/well and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 7 days. Cells were trypsinized and counted at days 1, 3, 5, and 7. Three independent experiments were performed.

Growth Transformation Assays

Serum dependence of cells for growth was determined as described previously.23 Briefly, LS-8, EV, S, and AS clones were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cell/well and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and allowed to adhere to the culture dish. Then, culture medium was changed to DMEM containing 1% FBS and cells were cultured for 7 days. Cells were trypsinized and counted at days 1, 3, 5, and 7.

To determine the ability of transfected cells to grow as multiple layers and form foci, focus formation assay was performed as previously described with modification.23 LS-8, EV, S, and AS clones were seeded in triplicate of 1 × 105 cell/60-mm cultured dish and maintained for 3 weeks. After that, cells were fixed with 3:1 (v/v) methanol:acetic acid, stained with 0.4% crystal violet in 20% ethanol, and photographed. Stained foci were counted to quantify the transforming activity.

To determine the anchorage-independent growth, soft agar assay was performed as previously described with modification.23 LS-8, EV, S, and AS clones were cultured and trypsinized to obtain single-cell suspensions. A total of 5 × 103 cells were suspended in DMEM containing 0.3% agar and were then seeded onto a 0.5% agar base in six-well plates. DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the top of the agar and was replaced twice weekly. Colony growth was assayed at 4 weeks after the initial seed. The number of colonies larger than 50 μm in diameter (containing >30 cells per colony) was counted in five random three-dimensional fields per well and photographed under 4× objective lens.

In Vivo Tumor Formation

To evaluate the tumorigenicity of the transfected cells, EV cells or cells highly overexpressing WNT5A (SH) were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nude mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) at seeding densities of 2 × 106 cells per site. Tumor development was monitored at an animal studies core facility (Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). Tumor measurements in three dimensions (length × width × depth) were taken by calipers three times per week over 12 weeks or until the tumor burden reached a volume of 1 cm3. At this point, tumors were excised immediately following euthanization, divided in half, and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological analysis or RNA-later solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) for RT-PCR. For histological analysis, tumors were embedded in paraffin and stained with H&E. For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated from each tumor by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized by using the Superscript RT kit (Invitrogen) followed by PCR. For WNT5A overexpressing tumors, PCR was performed by using T7 promoter (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) and Wnt5a (5′-TTTGCACACGAACTGATCCAC-3′) specific primers. For tumors formed by the EV group, PCR was done by using T7 promoter (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) and Bovine Growth Hormone (5′-CTAGAAGGCACAGTCGAGGCT-3′) primers.

Wound Healing Assay

Cells were grown on fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich) coated 60-mm dish supplemented with completed medium (10% FBS). After the cells reached 90% confluence, the medium was switched to 2.5% FBS and a wound was created by scratching a line across the monolayer of cells with a pipette tip.24 The number of cells migrating in to the space at 24 hours were counted in five random fields per group, photographed, and fixed with 3:1 (v/v) methanol: acetic acid, and stained with 0.4% crystal violet in 20% ethanol. Five independent experiments were performed with two replicates.

Actin Filament Staining

To visualize the change in actin filament organization, cells were grown on fibronectin coated glass coverslips, rinsed, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at 4°C. Next, cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at 4°C. Actin filaments were stained with a 50 μg/ml of fluorescein isothiocyanate phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The nuclei were counterstained with TOPRO-3 dye (Invitrogen). Fluorescent images were examined with Olympus FluoView FV500 confocal fluorescent microscope (Olympus Inc., Center Valley, PA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses in all experiments, except the immunohistochemistry, were performed by using Sigma stat software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test at P = 0.05. For immunohistochemical analysis, ameloblastoma samples were categorized into positive and negative groups, based on expression of WNT5A, and were then compared in regard to each clinicopathological variable including age, gender, tumor location, and histological types. The χ2 test was used for statistical analysis and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Expression of WNT5A in Ameloblastoma

We validated the specificity and sensitivity of anti- WNT5A antibody before using it in further experiments. Strong WNT5A expression was detected in mouse small intestine and hair follicle (Supplemental Figure 1, A and C, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org) since WNT5A is essential for mouse small intestine elongation and hair follicle development.25,26 As previously reported,27 weak or absent WNT5A expression was observed in adult mouse liver (Supplemental Figure 1E, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The results of immunohistochemistry demonstrated the presence of WNT5A in ameloblastomas (Figure 1A). The epithelial nests and/or strands exhibited strong positive staining. Slight WNT5A expression was also detected in the stromal component of ameloblastomas. WNT5A immunoreactivity in ameloblastoma was confirmed since the staining in both epithelium and stroma was absent when anti-WNT5A antibody was blocked with a recombinant WNT5A protein.

Figure 1.

Expression of WNT5A in ameloblastoma and during human tooth development. A: Ameloblastomas were immunostained with anti-WNT5A antibody (1:200) and images were captured under ×100 magnifications. Sections incubated with normal horse serum and recombinant WNT5A (rWNT5A) (2 μg/ml) blocked antibody were used as negative controls. Scale bar = 100 μm; n = 52. B: At the cap stage, WNT5A was localized in both outer (OE) and inner enamel epithelium (IE) but weakly detected in dental mesenchyme (DM). During the early bell stage, WNT5A remained in IE and presecretory ameloblasts (PAM) with intense expression around enamel knots (EK) and cervical loops (CL). At the late bell stage, WNT5A expression remained in EK and CL but was absent from mature or secretory ameloblasts (MAM), as well as dental papilla (DP) and developing odontoblasts (OD). Scale bar = 50 μm; n = 3. Arrows identify structures and cells defined by abbreviations.

Among 52 samples of first occurrence, solid/multicystic ameloblastoma, we found the major histological pattern of the tumors was the mixture of plexiform and follicular patterns (44%), followed by follicular (29%) and plexiform (27%) patterns. Expression of WNT5A was observed in 46 ameloblastomas (88%) regardless of the variation in histological subtype. We detected comparable levels of WNT5A expression among histologically different ameloblastoma patterns. Negative WNT5A expression was found in six cases (12%) and the major subtype of these ameloblastomas was the mixed plexiform and follicular pattern (67%). We were able to retrieve the clinicopathological features of tumors from 34 cases, and the data along with statistical analysis are shown in Table 1. Statistical analysis showed no significant correlation between WNT5A expression in ameloblastomas and any variables, such as age, gender, tumor location, and histological subtypes.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Features of Ameloblastoma in Relation to WNT5A Expression

| Variables | n | WNT5A+ | WNT5A− | χ20.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 34 | 30 | 4 | 0.78 |

| 0–20 | 9 | 8 | 1 | — |

| 20–40 | 13 | 12 | 1 | — |

| >40 | 12 | 10 | 2 | — |

| Sex | 34 | 30 | 4 | 0.92 |

| Male | 18 | 16 | 2 | — |

| Female | 16 | 14 | 2 | — |

| Tumor location | 34 | 30 | 4 | 0.73 |

| Maxilla | 11 | 10 | 1 | — |

| Mandible | 23 | 20 | 3 | — |

| Histological types | 52 | 46 | 6 | 0.53 |

| Follicular | 15 | 14 | 1 | — |

| Plexiform | 14 | 13 | 1 | — |

| Mixed | 23 | 19 | 4 | — |

Expression of WNT5A during Human Enamel Epithelium Development

To better understand the possible role of WNT5A in odontogenic tumors, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of the WNT5A expression during the development of normal human teeth (Figure 1B). Human molars at cap stage (13 to 16 gestational weeks) showed WNT5A localized in both outer and inner enamel epithelium but was weakly detected in dental mesenchyme. During early bell stage (16 to 18 gestational weeks), WNT5A expression was maintained in the inner enamel epithelium, outer enamel epithelium, and presecretory ameloblasts with intense expression around the enamel knot and cervical loop. At late bell stage (18 to 20 gestational weeks) when there was some deposition of enamel matrix, WNT5A expression remained in the enamel knot and cervical loop but was absent from secretory ameloblasts as well as dental papilla and developing odontoblasts.

Establishment and Characterization of LS-8 Derived Stable Clones

To determine the biological consequences of WNT5A expression in enamel epithelium, we overexpressed or underexpressed WNT5A in LS-8 cells. Full-length mouse Wnt5a constructs were generated and verified as bands at the expected size at 1140 bp (Supplemental Figure 2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The Wnt5a-PCR products were then ligated into pcDNA3.1 V5-His-TOPO mammalian expression vector. We stably transfected LS-8 cells with sense (pcDNA3.1/Wnt5a) or antisense (pcDNA3.1/ASWnt5a) constructs, and stable clones were selected in the presence of G418 (600 μg/ml) in 4 to 5 weeks after transfection. The EV clones (pcDNA3.1/V5-His B) were subjected to the same selection procedure and were used as controls. To ensure the secretion of WNT5A, expression of WNT5A into the conditioned medium generated from each stable clone was verified by Western blot. Due to WNT5A's highly hydrophobic nature, we adopted the Triton X-114 phase separation technique to concentrate and maintain solubility of WNT5A in conditioned medium.21,22 Results shown in Figure 2A illustrate that most secreted WNT5A partitioned to the detergent phase (De). Bands at the size of 42 kDa (asterisks in Figure 2A) represented endogenous WNT5A expressed in LS-8 (wild-type), S, and EV clones, while it disappeared from AS clone. Bands at approximately 47 kDa (arrow in Figure 2A) represented WNT5A recombinant proteins that were only expressed in sense transfected clones and confirmed the production of WNT5A from transfected constructs. Faint staining bands were seen at 47 kDa in the EV and wild-type cells and higher molecular weight bands in all cells representing weak binding to non-WNT5A proteins.

Figure 2.

Level of WNT5A production from different transfection. A: Secreted Wnt5a in conditioned medium was partitioned in detergent phase (De) but not aqueous phase (Aq) after Triton X-114 phase separation. The 42 kDa band of endogenous WNT5A (asterisks) was faintly visible in wild-type (WT), overexpressed (S) and empty vector (EV) transfections. The 47 kDa band of WNT5A fusion protein (arrow) was only detected in S transfected clones while WNT5A production was suppressed in AS transfections. B: Stable clones established from S transfection were selected and categorized according to level of expression in to high (SH), moderate (SM), and low (SL) overexpressing WNT5A clones. C: The endogenous Wnt5a (42 kDa) in EV clones was comparable with wild-type, while it was suppressed in AS stable clones. Cell lysate from NIH3T3 cell was used as a negative control. Three independent clones from each S group, together with EV and AS clones were selected for further experiments. D: Quantification of Wnt5a expression in selected stable clones by real-time PCR. Selected stable clones from S transfection showed increase in Wnt5a expression compared with wild-type and EV clones, 2.37-, 4.5-, and 7.97-fold increase in SL, SM, and SH respectively. Wnt5a expressions in stable clones from AS transfection were decreased by 0.13-fold.

When comparing the expression of WNT5A collected from cell surface and cell matrices, the level of WNT5A from S clones was classified into the following three groups: high; moderate; and low overexpression (SH, SM, and SL clones) as shown in Figure 2B. The endogenous WNT5A expression in EV clones was comparable with wild-type, while it was suppressed in AS stable clones (Figure 2C). Expression of Wnt5a in each selected clone was then quantified by real-time PCR (Figure 2D). Average expressions of Wnt5a in SH, SM, and SL clones showed 7.97, 4.5, and 2.3 fold increases respectively when compared with wild-type and EV clones. Wnt5a expression was decreased in selected AS clones by 0.13-fold. Three independent clones from each transfection were selected for next experiments.

Effects of WNT5A on In Vitro Cell Growth Transformation of Enamel Epithelium

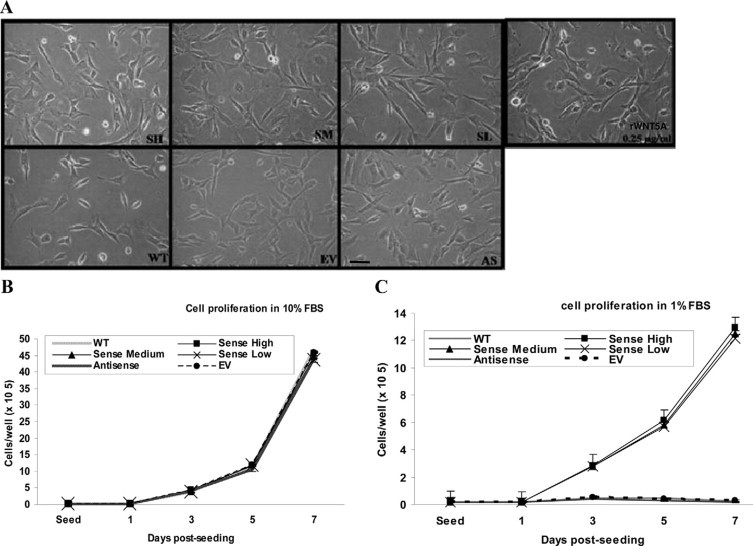

We next evaluated the growth properties of selected stable clones by in vitro cell growth transformation assay. EV, S, and AS clones showed similar morphology to wild-type (Figure 3A). Increased expression of WNT5A in enamel epithelium did not affect cell proliferation when cells were maintained in medium containing 10% FBS (Figure 3B). Interestingly, when cultured in serum-reduced condition that contained 1% FBS, only the WNT5A overexpressing clones survived in the serum-starved condition. S clones had dramatically decreased proliferation rates but survived up to 7 days in culture while wild-type, EV, and AS clones did not survive under reduced serum conditions (Figure 3C). This result suggested that WNT5A could promote less dependence of growth factor property on enamel epithelium.

Figure 3.

Cell morphology and proliferation assay of stable clones. A: No significantly different morphology was observed among wild-type (WT), EV, S, and AS clones. When recombinant WNT5A (rWNT5A) (0.25 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium, WNT5A treated LS-8 showed similar phenotype to wild-type. B: 1 × 105 cells WNT5A from each clone were plated and supplemented with medium containing 10% FBS. Proliferation rates were similar among all groups. C: When the same number of cells were cultured in 1% FBS medium, sense clones had a dramatically decreased proliferation rate but still survived in serum-reduced condition up to 7 days of culture. Wild-type, EV, and AS clones could not survive under these conditions. Original magnification, ×200. Scale bar = 100 μm.

WNT5A overexpressing clones also exhibited loss of contact inhibition of growth after confluence when tested with focus formation assay. Allowing growth beyond confluence, SH, SM, and SL clones formed multilayered of foci on culture dishes for up to 20 days (Figure 4A). Few foci were found in wild-type, EV, and AS clones. Numbers of foci formed by WNT5A overexpressing clones were correlated with the level of WNT5A expression (Figure 4B) suggesting that WNT5A could promote loss of contact inhibition in enamel epithelium in a dose dependent manner.

Figure 4.

WNT5A promoted loss of contact inhibition and anchorage-independent growth in enamel epithelium. A: SH, SM, and SL formed multilayered foci on culture dishes after being cultured for 3 weeks while few foci formations were found in wild-type (WT), EV, or AS clones. B: Numbers of foci formation were correlated with the level of WNT5A expression in overexpressed clones suggesting dose dependent effect. C: S clones formed visible colonies in soft agar within 2 weeks after seeding, whereas wild-type, EV, and AS clones failed to form visible colonies by bare eyes. D: The number of colonies formed by S clones corresponded to the level of WNT5A expression. Original magnification ×40. Scale bar = 200 μm. *P < 0.05 vs EV, **P < 0.05 vs. SH.

Next, we analyzed anchorage-independent of growth in these clones by soft agar assay. S clones formed visible colonies within 2 weeks after seeding (Figure 4C), whereas wild-type, EV, and AS clones did not form colony visible by bare eyes even after 4 weeks of culture. Similar to what we found in foci formation, the numbers of colony formed in soft agar by WNT5A overexpressing clones corresponded to their level of WNT5A expression (Figure 4D).

Finally, we determined if WNT5A overexpression could affect the tumorigenicity of LS-8 cells when subcutaneously transplant into nude mice. SH cells formed palpable tumors (approximately 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm3) in the mice within 4 days after injection (Figure 5A). Interestingly, EV cells also exhibited tumor formation at 18 days after injection. After monitoring for up to 48 days, all mice in the experiment developed tumors; however, SH cells appeared to develop tumors earlier than EV control cells. On average, mice injected with SH cells exhibited tumors within 18 days post implantation in contrast to the EV controls that developed tumors in 32 days. SH cells also had a faster tumor growth rate compared with the EV group when total tumor volume was calculated (Figure 5B). All tumors were solid masses, nonencapsulated but well circumscribed by peripheral connective tissue stroma. Connective tissue infiltrating area was rarely seen in these tumors. Histology of the tumors from both groups appeared to be similar (Figure 5C). They both were composed of a mixture of epithelium and mesenchyme. The tumors did not display a typical ameloblastoma-like histological appearance but did develop duct-like or follicular structures (arrow in Figure 5C) formed by cuboidal epithelium that were randomly distributed in the tumor with mesenchymal cells making up the majority of the tumor. Most of the mesenchymal cells were fibroblast-like, poorly differentiated, and were in active mitosis as shown by dense chromatin condensation. No calcifying areas or tooth-forming structure were observed in any of the tumors.

Figure 5.

Tumor formation in nude mice. WNT5A overexpressing (SH) or EV-LS-8 cells (2 × 106) were subcutaneously transplanted into nude mice (n = 8 per group). A: SH cells formed tumors within 4 days after injection. EV groups also exhibited tumor growth at 18 days. In average, SH cells exhibited tumors within 18 days post implantation compared with 32 days in the EV group. B: SH groups also showed faster tumor growth rates when total tumor volume was calculated. Tumor formation was monitored for up to 83 days. C: H&E staining of tumors formed in nude mice. Tumors histology appeared similar in both groups. The majority of the tumor mass comprised of mesenchyme with epithelium that randomly formed a duct-like structure (arrows). Scale bar = 50 μm; n = 8.

We performed RT-PCR to confirm the origin of the tumors. For tumors formed by SH cells, PCR using T7 forward and Wnt5a reverse primers generated the products approximately 1150 bp of the transfected and integrated Wnt5a plasmid (Supplemental Figure 3A, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). For tumors formed by EV group, PCR using T7 forward and Bovine Growth Hormone reverse primes yielded the 250 bp bands of integrated pcDNA3.1 V5-HisA empty vectors (Supplemental Figure 3B, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The detection of these PCR products indicated that tumors formed in nude mice were developed from injected enamel epithelium and not from the indigenous mouse cell populations.

WNT5A Increased Cell Migration and Actin Polymerization of Enamel Epithelium

Since WNT5A activation has been shown to promote cell migration,11 we examined whether WNT5A could induce actin filament rearrangement to regulate cell migration in enamel epithelium. A scratch wound was created on 90% of confluent monolayer of cells in culture medium containing 2.5% FBS to stimulate cell migration (Figure 6A). At 17 hours after scratching, the highest numbers of cells migrating into the created wounds were from S clones, moderate numbers from wild-type and EV and fewest numbers from AS clones. At 24 hours, cells from S clones were able to close the wound (Figure 6B). Although additional cells from wild-type and EV migrated to the space when compared with the results at 17 hours, they did not close the wound. Interestingly, only small number of cells from AS clones migrated into the created wound suggesting that WNT5A regulated enamel epithelium cell migration.

Figure 6.

WNT5A increased cell migration in enamel epithelium cells. A: 2 × 106 of cells were seeded onto the fibronectin coated 60-mm dish and supplemented with 2.5% FBS in DMEM. A scratch was made and cell migration into the space was monitored at 17 and 24 hours. WNT5A overexpressing cells (S) showed enhanced migration compared with EV control. In contrast, WNT5A underexpressing cells (AS) had greatly decreased cell migration. B: The number of migrated cells in to the space was quantified from five random fields. Original magnification ×100; scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 vs EV. C: Actin cytoskeleton was stained by using fluorescein isothiocyanate phalloidin (bright) and examined by using confocal microscopy. WNT5A overexpressing (S) cells showed a greatly increased density of stress fiber formation when compared with EV and AS cells. Filopodia and lamellipodia (arrows) were generally seen in WNT5A-S. D: The number of filopodia/lamellipodia was counted and shown as mean ± SD value from 20 cells/group. Original magnification ×600; scale bar = 20 μm.

Since the change in stress fiber formation is a necessary process in cell migration,28–30 we evaluated the role of WNT5A in this process by actin filament staining. Cells were plated on fibronectin coated coverslips. Actin cytoskeleton was stained by using fluorescein isothiocyanate phalloidin (Figure 6C). Consistent with the results of our cell migration assay, stress fiber formation density was greatly increased in the cells from S clones, but largely decreased in the cells from AS clones, when they were compared with EV cells. Interestingly, filopodia and lamellipodia, structures both of which are important for cell migration, were generally seen in WNT5A overexpressing cells (Figure 6, C and D), while WNT5A underexpressing cells appeared to form clusters with migratory structures rarely being seen. These results confirm that WNT5A induces enamel epithelium cell migration and this process involves actin cytoskeleton reorganization.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that ameloblastomas are highly consistent in their expression of WNT5A. While WNT5A expression is often associated with malignant tumors, ameloblastomas are benign but highly invasive tumors. Detection of WNT5A expression in granular cell ameloblastoma has been suggested by others,19 but for the first time our study reports the molecular consequences of WNT5A signaling activation in enamel epithelium cell.

In the present study, it is notable that comparable levels of WNT5A expression were found in the plexiform, follicular and mixed plexiform/follicular histological subtypes, the two most common variants of ameloblastoma. Interestingly, our study finds no statistically significant relationship between WNT5A expression and clinicopathological or demographic features. One possible reason for this result could be due to the relative consistency of tumor variety in our sample since the recurrence and/or malignant ameloblastomas are excluded. The authors of future studies evaluating recurrent ameloblastomas should investigate the distribution and level of WNT5A expression. Unfortunately the aggressiveness of ameloblastomas is not evaluated since all samples are graded as benign tumors and they are typically removed immediately following diagnosis.3,5,31 Although there is a difference in occurrence rates observed between subtypes, authors report no correlation among each histologically different pattern and aggressiveness of ameloblastoma.4,5,31

Enamel epithelial remnants from migrating enamel epithelium in the cervical loops are believed to give rise to odontogenic tumors. Interestingly, WNT5A expression in ameloblastoma is also intense in the epithelial compartment, which is similar to WNT5A detection in cervical loop. In the cancer stem cell theory, we know that many cancer cells display a stem-cell like phenotype. The result of cervical loop cells strongly expressing WNT5A provides further support for the assumption that enamel epithelium remnants from cervical loop are the cell of origin for odontogenic tumors.

One major difficulty in studying the molecular pathology of odontogenic tumors is the lack of appropriate cell lines and animal models. For the cell origin of odontogenic tumors, LS-8 cell exhibits several characteristics including the expression of enamel matrix genes, such as amelogenin and ameloblastin, making it suitable for these studies.20,32 LS-8 cells are the most widely use in vitro model to study enamel epithelium biology and gene regulation of ameloblast development.32–35 Since LS-8 cells are immortalized by Simian virus 40 large T antigen, the interpretation of our results should be done with some caution. Interestingly, we observed in in vivo tumor formation assays that LS-8 cell populations had already acquired some growth transformation properties. Although wild-type LS-8 and EV cells form fewer colonies in soft agar and tumors in nude mice, statistically significant differences were observed with S cells that showed robust activities in all cell growth transformation assays. In the in vivo tumor formation assay, SH cells formed tumors 2 weeks earlier and exhibited faster tumor growth rates compared with EV cells. These phenomena could be partly explained by the potential function of WNT5A as an oncogenic enhancer. LS-8 cells potentially obtained some tumorigenicity from Simian virus 40 large T antigen, and WNT5A, therefore, enhances tumorigenicity of these cells. WNT5A was categorized as nontransformed WNT due to the inability to transform mammary epithelial cells,36,37 but its transforming property has rarely been tested in other cell models. In fact, WNT5A signaling outcomes are largely dependent on receptors availability.11,38 More recently, the line of evidence leans toward the fact that the major role of WNT5A in cancer is to promote the aggressiveness of cancer cells rather than cancer initiation.11 Our observations from cell growth transformation assays also suggest that WNT5A functions as an enhancer to increase the oncogenic properties in LS-8 cells. Whether WNT5A can function as an oncogenic transformer is still inconclusive.

It is notable that histology of the tumors formed in both groups appears to be similar with the bulk of the cells being mesenchymal even though the cells being injected were epithelial. RT-PCR showed that these tumors developed from the injected enamel epithelium cells since the integrated empty vector and Wnt5a plasmids were detected from tumor RNA. It is possible that the LS-8 cells could have undergone epithelium-mesenchyme transition. Additionally, WNT5A has been associated with the loss of E-cadherin and epithelium-mesenchyme transition expression in squamous cell carcinoma.39 Another possible explanation is based on the fact that enamel epitheliums are able to induce proliferation and differentiation of surrounding mesenchyme (odontoblast during tooth development). LS-8 cells might induce improper proliferation and differentiation of surrounding mesenchyme and secreted WNT5A from LS-8 cells could function in a paracrine manner to help accelerate this process. Although the histology of these tumors differed from the typical ameloblastoma and the area of tooth forming-like structure was not observed, this result was not surprising. Since the environment at the inoculating sites was considerably different from the jaws, the lack of reciprocal dental related cells could explain this finding. Injection of LS-8 cells into the jaw area should be considered in future experiments to create a potentially more appropriate environment for odontogenic tumor development.

The function of WNT5A in cell migration is another controversial subject evaluated by our studies. WNT5A suppresses migration and invasion of breast epithelial cells.40,41 On the other hand, WNT5A increases cell migration and invasion in melanoma cell, fibroblast, and breast cancer.12,42,43 In our study, we found that WNT5A drastically promoted cell migration in LS-8 cells. This effect was due to increased cell migration rather than cell proliferation since the experiment was done in cultured medium containing 2.5% FBS and WNT5A had no effect on LS-8 cells when tested with the cell proliferation assay. Cells overexpressing WNT5A also exhibited actin rearrangement and formed lamellipodia and filopodia at the edges of the cells. When endogenous WNT5A was suppressed, AS cells failed to form significant actin reorganization and membrane protrusion was rarely seen. Therefore, our data indicate a role for WNT5A in regulating enamel epithelium cell motility by increasing actin reorganization and extension that generates the force for cell movement.

The fact that WNT5A is shown to promote cancer aggressiveness and metastasis in many types of cancer could suggest the possible role of WNT5A in ameloblastoma progression. In melanoma, WNT5A was predominantly detected in the leading front of cancer invasion while other areas showed weaker expression,12 suggesting the effect of differential WNT5A expression on tumor cell behavior. This could be extrapolated to the slow growing nature of ameloblastomas that might be regulated by the temporal WNT5A expression where tumors actively grow when WNT5A is expressed, and the tumor cells are in resting stage when WNT5A expression is down-regulated. In summary, our results demonstrate that WNT5A overexpression has multiple effects on enamel epithelial cells. WNT5A has the effect of promoting cell survival, instilling a loss of contact inhibition and loss of anchorage dependence, and allowing an increase in cell migration, which are all important characteristics of tumorigenic cells. Taken together, this knowledge strongly suggests the importance of WNT5A during ameloblastoma development and inhibition of WNT5A signaling could possibly serve an effective therapeutic approach to preserve the jaw from radical excision treatment and prevent the recurrence of this tumor.

Acknowledgements

We thank Malcolm Snead (University of Southern California) for providing LS-8 cells; and Bernard Weissman, Eric Everett, Yoshiyuki Mochida, and Valerie Murrah (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants DE533921 (J.T.W.) and Anandamahidol Foundation Ph.D. Scholarship (W.S.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

Web Extra Material

Validation of WNT5A antibody specificity. Strong WNT5A expression was detected in mouse small intestine (a) and hair follicles (c) and the immunoreactivity was diminished when the antibody was blocked with recombinant WNT5A (2 μg/ml) ((b) and (d)). Adult mouse liver was used as a negative control where no expression of WNT5A was detected when WNT5A antibody alone (e) and blocked WNT5A antibody (f) were used. (Antibody dilution 1:200), (Magnification x100), (Bar, 100 μm)

Wnt5a PCR product and restriction enzyme analysis of pcDNA3.1 vectors harboring Wnt5a cDNA. The full length-Wnt5a amplicon from mouse kidney is 1140 bp (lane 4). pcDNA3.1/Wnt5a digested with HindIII and XhoI demonstrated that the correct size of full length-Wnt5a was inserted in to the vectors. Uncutted pcDNA3.1 vectors harboring Wnt5a cDNA is seen in lane 1. The sense construct is shown in lane 2 and the antisense construct was appears in lane 3. Orientation of all inserts was verified by DNA sequencing.

RT-PCR of the tumors formed in nude mice. (A), Bands of integrated Wnt5a plasmid approximately 1150 bp were detected in tumors overexpressing Wnt5a using T7 forward and Wnt5a reverse primers. (B), Tumors formed in the EV group yielded the approximately 250 bp band of integrated pcDNA3.1 V5-HisA Empty vectors when evaluated using PCR with T7 forward and BGH reverse primers.

References

- 1.Hamamoto Y, Hamamoto N, Nakajima T, Ozawa H. Morphological changes of epithelial rests of Malassez in rat molars induced by local administration of N-methylnitrosourea. Arch Oral Biol. 1998;43:899–906. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(98)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Ogawa I, Suei Y, Takata T. The inflammatory paradental cyst: a critical review of 342 cases from a literature survey, including 17 new cases from the author's files. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichert P, Sidransky D. World Health Organization classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. IARC Press; Lyon: 2005. pp. 1–430. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neville BW. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia; Toronto: 2008. pp. 1–984. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology. Mosby; St. Louis: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Chen XM, Sun ZJ, Bian Z, Fan MW, Chen Z. Epithelial expression of SHH signaling pathway in odontogenic tumors. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohki K, Kumamoto H, Ichinohasama R, Sato T, Takahashi N, Ooya K. PTC gene mutations and expression of SHH, PTC, SMO, and GLI-1 in odontogenic keratocysts. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumamoto H, Ooya K. Immunohistochemical detection of beta-catenin and adenomatous polyposis coli in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:401–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassanein AM, Glanz SM, Kessler HP, Eskin TA, Liu C. beta-Catenin is expressed aberrantly in tumors expressing shadow cells: pilomatricoma, craniopharyngioma, and calcifying odontogenic cyst. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:732–736. doi: 10.1309/EALE-G7LD-6W71-67PX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danielson KG, Pillarisetti J, Cohen IR, Sholehvar B, Huebner K, Ng LJ, Nicholls JM, Cheah KS, Iozzo RV. Characterization of the complete genomic structure of the human WNT-5A gene, functional analysis of its promoter, chromosomal mapping, and expression in early human embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31225–31234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pukrop T, Binder C. The complex pathways of Wnt 5a in cancer progression. J Mol Med. 2008;86:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weeraratna AT, Jiang Y, Hostetter G, Rosenblatt K, Duray P, Bittner M, Trent JM. Wnt5a signaling directly affects cell motility and invasion of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CL, Liu D, Nakano J, Ishikawa S, Kontani K, Yokomise H, Ueno M. Wnt5a expression is associated with the tumor proliferation and the stromal vascular endothelial growth factor: an expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8765–8773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Williamson M, Bott S, Brookman-Amissah N, Freeman A, Nariculam J, Hubank MJ, Ahmed A, Masters JR. Hypomethylation of Wnt5a, CRIP1 and S100P in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:6560–6565. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dejmek J, Dejmek A, Safholm A, Sjolander A, Andersson T. Wnt-5a protein expression in primary dukes B colon cancers identifies a subgroup of patients with good prognosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9142–9146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iozzo RV, Eichstetter I, Danielson KG. Aberrant expression of the growth factor Wnt-5A in human malignancy. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3495–3499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang H, Chen Q, Coles AH, Anderson SJ, Pihan G, Bradley A, Gerstein R, Jurecic R, Jones SN. Wnt5a inhibits B cell proliferation and functions as a tumor suppressor in hematopoietic tissue. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sathi GS, Han PP, Tamamura R, Nagatsuka H, Hu H, Katase N, Nagai N. Immunolocalization of cell signaling molecules in the granular cell ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LS, Couwenhoven RI, Hsu D, Luo W, Snead ML. Maintenance of amelogenin gene expression by transformed epithelial cells of mouse enamel organ. Arch Oral Biol. 1992;37:771–778. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(92)90110-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR, 3rd, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurayoshi M, Yamamoto H, Izumi S, Kikuchi A. Post-translational palmitoylation and glycosylation of Wnt-5a are necessary for its signalling. Biochem J. 2007;402:515–523. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox AD, Der CJ. Biological assays for cellular transformation. Methods Enzymol. 1994;238:277–294. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)38026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valster A, Tran NL, Nakada M, Berens ME, Chan AY, Symons M. Cell migration and invasion assays. Methods. 2005;37:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cervantes S, Yamaguchi TP, Hebrok M. Wnt5a is essential for intestinal elongation in mice. Dev Biol. 2009;326:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy S, Andl T, Bagasra A, Lu MM, Epstein DJ, Morrisey EE, Millar SE. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XH, Pan MH, Lu ZF, Wu B, Rao Q, Zhou ZY, Zhou XJ. Expression of Wnt-5a and its clinicopathological significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazaki D, Kurisu S, Takenawa T. Regulation of cancer cell motility through actin reorganization. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambrechts A, Van Troys M, Ampe C. The actin cytoskeleton in normal and pathological cell motility. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1890–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soames JV, Southam JC, editors. Oral pathology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z, Sargeant TD, Hulvat JF, Mata A, Bringas P, Jr, Koh CY, Stupp SI, Snead ML. Bioactive nanofibers instruct cells to proliferate and differentiate during enamel regeneration. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1995–2006. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou YL, Lei Y, Snead ML. Functional antagonism between Msx2 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha in regulating the mouse amelogenin gene expression is mediated by protein-protein interaction. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29066–29075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Tannukit S, Zhu D, Snead ML, Paine ML. Enamel matrix protein interactions. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1032–1040. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubota K, Lee DH, Tsuchiya M, Young CS, Everett ET, Martinez-Mier EA, Snead ML, Nguyen L, Urano F, Bartlett JD. Fluoride induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in ameloblasts responsible for dental enamel formation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23194–23202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong GT, Gavin BJ, McMahon AP. Differential transformation of mammary epithelial cells by Wnt genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6278–6286. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson DJ, Papkoff J. Regulated expression of Wnt family members during proliferation of C57mg mammary cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikels AJ, Nusse R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taki M, Kamata N, Yokoyama K, Fujimoto R, Tsutsumi S, Nagayama M. Down-regulation of Wnt-4 and up-regulation of Wnt-5a expression by epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jonsson M, Andersson T. Repression of Wnt-5a impairs DDR1 phosphorylation and modifies adhesion and migration of mammary cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2043–2053. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.11.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonsson M, Dejmek J, Bendahl PO, Andersson T. Loss of Wnt-5a protein is associated with early relapse in invasive ductal breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishita M, Yoo SK, Nomachi A, Kani S, Sougawa N, Ohta Y, Takada S, Kikuchi A, Minami Y. Filopodia formation mediated by receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is required for Wnt5a-induced cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:555–562. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pukrop T, Klemm F, Hagemann T, Gradl D, Schulz M, Siemes S, Trumper L, Binder C. Wnt 5a signaling is critical for macrophage-induced invasion of breast cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5454–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509703103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Validation of WNT5A antibody specificity. Strong WNT5A expression was detected in mouse small intestine (a) and hair follicles (c) and the immunoreactivity was diminished when the antibody was blocked with recombinant WNT5A (2 μg/ml) ((b) and (d)). Adult mouse liver was used as a negative control where no expression of WNT5A was detected when WNT5A antibody alone (e) and blocked WNT5A antibody (f) were used. (Antibody dilution 1:200), (Magnification x100), (Bar, 100 μm)

Wnt5a PCR product and restriction enzyme analysis of pcDNA3.1 vectors harboring Wnt5a cDNA. The full length-Wnt5a amplicon from mouse kidney is 1140 bp (lane 4). pcDNA3.1/Wnt5a digested with HindIII and XhoI demonstrated that the correct size of full length-Wnt5a was inserted in to the vectors. Uncutted pcDNA3.1 vectors harboring Wnt5a cDNA is seen in lane 1. The sense construct is shown in lane 2 and the antisense construct was appears in lane 3. Orientation of all inserts was verified by DNA sequencing.

RT-PCR of the tumors formed in nude mice. (A), Bands of integrated Wnt5a plasmid approximately 1150 bp were detected in tumors overexpressing Wnt5a using T7 forward and Wnt5a reverse primers. (B), Tumors formed in the EV group yielded the approximately 250 bp band of integrated pcDNA3.1 V5-HisA Empty vectors when evaluated using PCR with T7 forward and BGH reverse primers.