Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass is essential to preserve sufficient insulin levels for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Previously, we reported that DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) resulting from nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) deficiency induce apoptosis and, when combined with p53 deficiency, progressed rapidly into lymphomagenesis in mice. Combination of NHEJ deficiency with a hypomorphic mutation, p53R172P, leads to the abrogation of apoptosis, upregulation of p21, and senescence in precursor lymphocytes. This was sufficient to prevent tumorigenesis. However, these mutant mice succumb to severe diabetes and die at an early age. The aim of this study was to determine the pathogenesis of diabetes in these mutant mice.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We analyzed the morphology of the pancreatic islets and the function, proliferation rate, and senescence of β-cells. We also profiled DNA damage and p53 and p21 expression in the pancreas.

RESULTS

NHEJ-p53R172P mutant mice succumb to diabetes at 3–5 months of age. These mice show a progressive decrease in pancreatic islet mass that is independent of apoptosis and innate immunity. We observed an accumulation of DNA damage, accompanied with increased levels of p53 and p21, a significant decrease in β-cell proliferation, and cellular senescence in the mutant pancreatic islets.

CONCLUSIONS

Combined DSBs with an absence of p53-dependent apoptosis activate p53-dependent senescence, which leads to a diminished β-cell self-replication, massive depletion of the pancreatic islets, and severe diabetes. This is a model that connects impaired DNA repair and accumulative DNA damage, a common phenotype in aging individuals, to the onset of diabetes.

Classic nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) is one of the two major pathways for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (1). The factors involved in this conserved pathway are the DNA-dependent kinase complex (DNA-PKcs) and Ku heterodimer, the DNA ligase complex (DNA ligase IV, XRCC4, Cernunnos/XLF), and a DNA repair factor Artemis (2). DNA ligase IV and XRCC4 are absolutely required for the classic NHEJ pathway; deficiencies of either render the cell hypersensitive to DNA-damaging agents, such as ionizing radiation, and premature senescence (3).

Mice deficient for NHEJ factors other than Cernunnos/XLF (4) develop severe combined immunodeficiency due to their failure to join DNA breaks generated during early lymphoid development in a DNA rearrangement process termed V(D)J recombination (5). NHEJ deficiency results in the accumulation of unrepaired DNA breaks and p53-dependent apoptosis in developing lymphoid cells. Some NHEJ-deficient mice also exhibit defective neuronal development, and an accumulation of DNA damage in the central nervous system that leads to p53-dependent apoptosis, in severe cases such as ligase IV (Lig4)−/− or XRCC4−/−, results in embryonic lethality (6–8).

The embryonic lethality is rescued by p53 deficiency (6,9). Lig4−/− or XRCC4−/− in the p53−/− background can survive after birth, but succumb to aggressive pro-B lymphomas at an early age (10). All these lymphomas carry chromosomal translocations between the immunoglobulin and the proto-oncogene c-MYC loci and a complicon structure that leads to amplification of the MYC genes. Interestingly, a hypomorphic mutant p53, p53R172P (referred to as p53p/p), which is defective in apoptosis but not in cell cycle arrest (11), not only rescues embryonic lethality but also entirely eliminates lymphomagenesis in the Lig4−/− (12). Analyses of Lig4−/−p53p/p mice revealed extensive senescence in developing lymphocytes with increased levels of p53 and p21. This indicates that V(D)J recombination-mediated DSBs, which are unrepaired due to a lack of end-joining, activate the hypomorphic p53, thereby transactivating p21 and ultimately driving these cells into senescence. This p53-p21–driven senescence has proven effective for suppressing genomic instability and tumorigenesis in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice.

Despite its potent tumor suppressor activity, cellular senescence has been described as a mechanism to prevent cell proliferation as well as resistance to apoptosis. These properties may cause aging-related diseases (13). Although DNA damage–induced senescence successfully prevents lymphomagenesis, all Lig4−/−p53p/p mice have an aging appearance and die before they reach 6 months of age. We hypothesize that DNA damage–induced senescence may lead to a decrease in cellular proliferation and organ regeneration or renewal capability. As a result, the maintenance of homeostasis is compromised. Indeed, analysis of these mice revealed a gradual depletion of pancreatic islets and progressive diabetes.

Diabetes arises because of defects in pancreatic β-cells, affecting either cell proliferation and growth or insulin production, which are crucial for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. β-Cell replication and islet mass are highly regulated by intrinsic genetic programs, extrinsic growth factors, and hormone levels in response to various challenges and physiological demands (14,15). Regulation of β-cell mass includes constant cell proliferation throughout life, although at different rates over time; continual cellular turnover is governed by the renewal and loss of β-cells by mechanisms such as apoptosis (16). Disruption of this balance leads to rapid changes in β-cell mass and pathological conditions such as diabetes. Because in adult mice β-cell self-replication is the main mechanism to regenerate and maintain the β-cell mass (17–20), DNA damage and its cellular response may disrupt cell proliferation thus leading to an imbalance of β-cell mass maintenance. Several reports have revealed that senescence induced by telomeric shortening or other means has been linked to limiting β-cell proliferation and diabetes (21,22). DNA damage has been considered an extrinsic factor contributing to cellular senescence, but its impact on pancreatic β-cells has not been addressed. In this report, we describe the first animal model that progressively develops diabetes with a depletion of pancreatic β-cell mass due to accumulated DNA damage and a p53-dependent response that drives cells into senescence. Our model indicates that age-related DNA damage accumulation in the pancreatic β-cells, and its associated senescence, may be one cause of diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Animals.

Mutant mice (mixed C57BL/6 and 129SV) maintenance has been previously described (12). The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Measurement of blood glucose and insulin levels.

For the glucose tolerance test, mice were fasted for 16 h and injected intraperitoneally with glucose at 1.0 g/kg body wt. For the insulin tolerance test, mice were fasted for 6 h and injected intraperitoneally with insulin at 0.75 units/kg (Sigma). Glucose levels were measured using a glucose analyzer (Bayer Contour). Blood insulin levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Pancreatic histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence.

Pancreata were fixed in Shandon Cryomatrix (Thermo Scientific) and placed at −20°C or Bouin solution (Ricca Chemical Company) overnight, dehydrated through ethanol, and embedded in paraffin for histological analysis. Sections (6 μm) were incubated with antibodies against insulin, glucagon (Cell Signaling), F480 (eBioscience), Cd11b, Nk1.1 (BD), p53 and p21 (Santa Cruz), or γH2AX (Abcam). For immunohistochemistry, horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies were applied per the manufacturer's recommendations. A 3,3′-diaminodbenzidine (DAB)-chromogen substrate mixture was applied or combined with 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (AEC) for double immunohistochemical detection. Slides were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) staining and examined by light microscopy (Olympus BX41). For immunofluorescence, secondary antibodies were applied according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Slides were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy.

Analysis of pancreatic morphology.

Pancreata sections were prepared as described; insulin was detected by immunohistochemistry and counterstained with H-E. Each section was subjected to morphometric analysis using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD). The area of the pancreas and the area of each islet in the tissue were measured. Raw data were statistically analyzed.

TUNEL assay.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (Promega) was used to detect apoptosis with DNase-1–treated sections as positive controls (12).

Pancreatic β-cell proliferation.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was injected intraperitoneally at 100 mg/kg. After 4 h, pancreata were sectioned. Slides were incubated with anti-BrdU (Serotec) and anti-insulin antibodies and analyzed.

Cell senescence.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity was detected by a staining kit (Cell Signaling). Blocks were sectioned (6 μm), and insulin was detected by immunohistochemical staining. Slides were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Labs).

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as the means ± SEM. Differences were determined using a two-tailed, unpaired Student t test with CI of 95%. A P value <0.05 was denoted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Lig4−/−p53p/p mutant mice exhibit glucose intolerance and impaired insulin production.

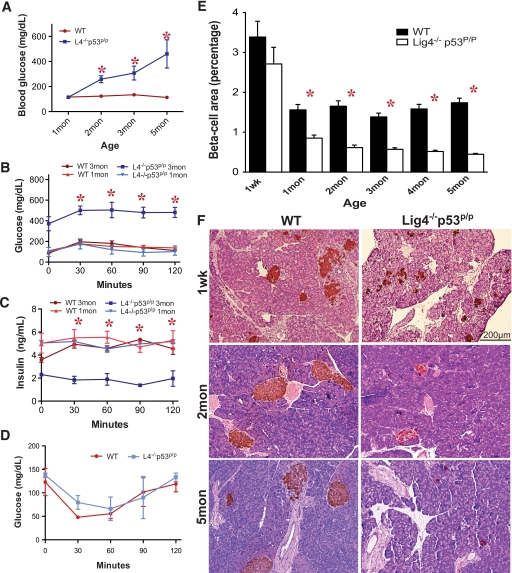

We previously showed that Lig4−/−p53p/p mice do not develop lymphomas or any other type of tumors, but die within 6 months of age (12). These mice appeared emaciated, lethargic, and dehydrated prior to death and presented severe hyperglycemia. We monitored nonfasting Lig4−/−p53p/p mice at different ages and found a progressive increase of blood glucose levels that was significantly different from the age-matched wild-type mice (Fig. 1A). Significant hyperglycemia was recorded as early as 2 months of age, suggesting a postnatal development of diabetes in the Lig4−/−p53p/p mice.

FIG. 1.

Lig4−/−p53p/p mice succumb to progressive diabetes and reduction of pancreatic islets. A: Blood glucose concentrations from nonfasting animals at indicated ages. Glucose levels were significantly higher in mutant mice starting at 2 months of age. Each data point was an average of at least three animals. B: Blood glucose concentrations measured from a glucose tolerance test in wild-type and Lig4−/−p53p/p mice at 1 and 3 months. Three mice from each genotype were tested. C: Blood insulin concentrations were measured by ELISA. D: Standard insulin tolerance test for insulin sensitivity in 1-month-old wild-type and Lig4−/−p53p/p mice. E: Islet morphometric quantification of Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice. Multiple sections were analyzed for each pancreas, and three to four mice per group were analyzed; data represent the means ± SEM. F: Representative pancreatic sections from Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice stained by immunohistochemistry for insulin. *P < 0.0001 versus wild type. Mon, month; Wk, week; WT, wild type. (A high-quality color digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

To determine the time of diabetes onset, we performed a standard glucose tolerance test in 1- and 3-month-old mutant mice with wild-type mice as controls. The glucose tolerance test at 1 month of age did not exhibit a significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 1B). However, 3-month-old Lig4−/−p53p/p mice showed hyperglycemia at point zero, and after the glucose injection the levels increased and remained high during the assay. These results indicate a progressive impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in the mutant mice. We next determined the blood insulin levels by ELISA in these mice. Although blood insulin levels were not significantly different at 1 month of age, insulin levels in the 3-month-old mutant mice were significantly lower and were irresponsive to the glucose injection, suggesting insulin insufficiency in these mice (Fig. 1C). Insulin tolerance test performed on 1-month-old mutant and wild-type mice revealed no difference between the two genotypes, indicating a normal insulin sensitivity in these mutant mice prior to diabetes onset (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these results indicate a progressive insufficient production of insulin that results in impaired glucose tolerance in the mutant mice.

Progressive depletion of pancreatic β-cells in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice.

Insulin insufficiency is a common characteristic in both types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes results from the combined effects of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors that destroy pancreatic β-cells (23). Type 2 diabetes results from a progressive islet dysfunction leading to defective β-cell secretion and insulin resistance (24,25). In both cases β-cell mass decreases, and residual functional β-cells still exist but are insufficient in number to maintain glucose tolerance. To determine whether the hyperglycemia observed in the Lig4−/−p53p/p mice was the result of a progressive decrease in β-cell mass, we examined the morphological changes in the pancreatic islets by H-E and immunohistochemical staining for insulin. As shown in Fig. 1E, mutant mice have a relatively normal size of pancreatic islets compared with the wild-type at 1 week of age. However, as mutant mice aged, the size of the pancreatic islets gradually declined. As shown in Fig. 1F, a significant decrease in islet size was observed in the mutant mice as early as 1 month of age. An almost complete depletion of the pancreatic islets was observed in the 5-month-old mutant mice. Immunohistochemical staining for glucagon, indicative of α-cells that signal the liver to break down glycogen to produce glucose upon hypoglycemia, did not reveal any abnormalities in these mutant mice. A full panel of islet histology is shown in supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, which are available in the online appendix at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/db09-0792/DC1.

To obtain a quantitative measurement and assess the differences of β-cell mass in Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice, we determined the ratio of islet area to total pancreas area. Islet size was nearly normal at 1 week of age (P < 0.2452; Fig. 1E). In general, older mutant mice observed a major reduction in pancreatic islet area. A 46% reduction in islet area was observed in the mutant mice at 1 month (P < 0.0001), although there was no difference in the ratio of pancreas to body weight between mutant and wild-type mice (supplementary Fig. 3). By 5 months of age, a 73% decrease was observed in the mutant mice (P < 0.0001). These results clearly indicate a severe reduction of the pancreatic islet mass in the mutant mice, correlating with progressive onset of diabetic phenotype.

Depletion of the pancreatic islets is not due to apoptosis or innate immunity.

Many diabetic models with resulting β-cell loss are due to an increase in islet-specific apoptosis (26,27). Although the p53R172P mutation prevents the induction of apoptosis, programmed cell death may occur independently of p53 expression (28). To test whether apoptosis is the cause of pancreatic islet depletion observed in mutant mice, we performed a TUNEL assay in pancreatic sections. No apoptosis was observed in 1-month-old mutant pancreatic sections, whereas only a very low level of apoptosis was observed in wild type at this age (supplementary Fig. 4) compared with an NHEJ-deficient thymus section. Similar results were obtained with mice at different ages (results not shown). These data suggest that pancreatic islet depletion observed in the Lig4−/−p53p/p mice is not due to DNA damage–induced apoptosis.

Type 1 diabetes is caused by activated immune cells specifically attacking pancreatic islets that leads to β-cell depletion. This is unlikely to happen in the Lig4−/−p53p/p mice as they are deficient in lymphocytes due to an incomplete V(D)J recombination. Instead, we examined whether the innate branch of immunity has any involvement in β-cell depletion. Pancreatic sections from mice of different ages were stained for CD11b surface markers, which identify infiltrated granulocytes, monocytes, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Although many cells were CD11b positive in the control spleen section, very few cells were stained positive for CD11b in both mutant and wild-type pancreatic sections, with undistinguishable differences. We also stained for the presence of infiltrated macrophages and mast cells using the F4-80 antibody and toluidine blue, respectively. Similar to CD11b staining, macrophage and toluidine blue–positive cells were rarely detected in pancreatic sections from both wild-type and mutant mice (supplementary Fig. 5). Collectively, these results suggest that it is unlikely that innate immune cells are responsible for the destruction of the pancreatic islets in the mutant mice.

Accumulated DNA damage in the pancreas of Lig4−/−p53p/p mutant mice.

Due to the high energy consumption, pancreatic β-cells are particularly susceptible to DNA damage caused by intrinsic metabolic agents such as reactive oxygen species (29). Because these cells are able to self-replicate, it is absolutely vital to have an efficient DNA damage repair machinery to maintain the integrity of the genome. Therefore, we hypothesized that the NHEJ pathway may be very active in pancreatic β-cells. To test this hypothesis, we performed a Western blot on purified wild-type pancreatic islets. Our results showed that indeed DNA ligase IV level is high in pancreatic islets (supplementary Fig. 6) and is comparable with the level detected in the testis, a tissue that is known to have high DNA ligase expression (30).

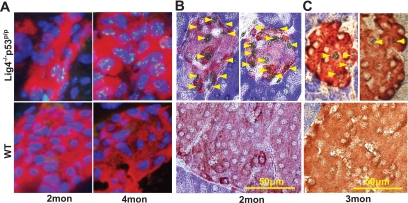

The high expression level of DNA ligase IV in pancreatic islets led us to predict that DNA damage should accumulate in pancreatic islets of Lig4−/−p53p/p mice (3). To determine whether γH2AX foci, indicative of DNA damage, accumulate in the mutant pancreas, we stained 2- and 4-month-old pancreatic sections from the Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice. γH2AX foci were detected throughout the 2-month-old mutant but not in the wild-type sections. By 4 months, intense γH2AX foci were observed in most mutant sections, indicating DNA damage was accumulative; this is in clear contrast to the absence of foci observed in the wild-type pancreas. Furthermore, sections that were costained for insulin and γH2AX showed high DNA damage in the pancreatic islets (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that in the absence of classic NHEJ, pancreatic islets suffer from gross accumulative DNA damage.

FIG. 2.

Accumulation of DNA damage and elevated p53 and p21 in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice. A: Pancreatic sections were stained for insulin by immunofluorescence (red), γH2AX foci (green), and DAPI (blue) in 2- and 4-month-old Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice. γH2AX foci visualized in Lig4−/−p53p/p are more intense in 4- than in 2-month-old mutant mice. No γH2AX foci were visible in wild-type mice. Double immunohistochemical staining of pancreatic sections from 2- or 3-month-old Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice for (B) p21 and (C) p53 (black) in combination with insulin (red-brown). Magnification ×40. Mon, month; WT, wild type. (A high-quality color digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Elevation of p53 and p21 results in cellular senescence in the pancreas of Lig4−/−p53p/p mutant mice.

NHEJ deficiency results in the failed end-joining of Rag-mediated DNA breaks in the thymus and bone marrow of Lig4−/−p53p/p mice, leading to activation of p53 and p21, as previously reported (12). We asked whether accumulated DNA damage in the pancreas also stimulates p53 and p21 expression in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice. Because DNA damage occurs randomly in the pancreas, as opposed to the programmed DNA damage in developing lymphocytes, we did not detect a similar expression of p53 and p21. However, p53 and p21 were detected in some pancreatic islets of mutant mice (Fig. 2B and C). Virtually no p53 or p21 was detected in age-matched wild-type pancreatic sections. These results indicate that accumulated DNA damage induces a p53-p21–dependent response in the pancreas of the Lig4−/−p53p/p mice.

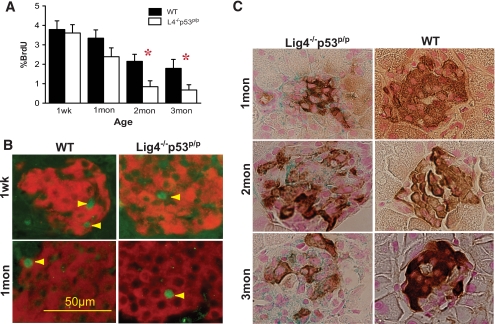

Decreased proliferation of β-cells in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice.

Slow proliferation is a major source for the maintenance of pancreatic β-cell mass and glucose homeostasis (17,18). We hypothesized that exposure to chronic DNA damage could lead to suppression in β-cell proliferation that eventually results in the loss of β-cell mass in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice. To test this hypothesis, we compared the β-cell proliferation rates by BrdU incorporation. Proliferating pancreatic cells, positive for incorporated BrdU, were identified by immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent staining. No differences in proliferation rates were observed at 1 week of age, but a discrete nonsignificant 28% decrease (P < 0.285) in β-cell proliferation was observed in pancreas of 1-month-old Lig4−/−p53p/p mice (Fig. 3A). A significant decrease of 60% (P < 0.0001) and 62% (P < 0.05) in β-cell proliferation was observed in 2- and 3-month-old mutant mice, respectively, as opposed to their wild-type counterparts. Representative sections are shown in Fig. 3B. These results strongly correlate with the appearance of the diabetic phenotype, suggesting a direct relationship between the decline in β-cell proliferation, due to the accumulation of DNA damage, and the onset of diabetes.

FIG. 3.

Decreased β-cell proliferation and increased cellular senescence in Lig4−/−p53p/p mice. A: Percentage of BrdU incorporation in β-cells of the total β-cells was measured in each age group of Lig4−/−p53p/p mice and plotted in comparison with age-matched wild-type mice. n ≥ 2 mice per time point. Data are the means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus wild type. B: Representative islet proliferation of pancreatic sections incubated with anti-BrdU antibody (green) and costained with anti-insulin antibody (red). Arrows indicate BrdU-positive cells. Magnification ×40. C: Immunohistochemical staining for insulin (brown) and β-gal (blue) staining of pancreatic sections from age-matched Lig4−/−p53p/p and wild-type mice. Counterstaining with nuclear fast red. Magnification ×100. Mon, month; Wk, week; WT, wild type. (A high-quality color digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Activated p53-p21 promotes cellular senescence as a mechanism to suppress genomic instability and tumorigenesis in the thymus and bone marrow of the mutant mice. We asked whether the random accumulation of DNA damage, which induces p53-p21 activation, could also render pancreatic cells to undergo cellular senescence. Pancreata from mutant and age-matched wild-type mice were stained for acidic β-gal activity, which indicates cellular senescence. The results demonstrated progressive β-gal accumulation in all three mutant mice at 1, 2, and 3 months of age. Importantly, positive β-gal staining is colocalized with insulin-positive islets, indicating those insulin-producing β-cells were undergoing senescence (Fig. 3C). No senescent cells were detected in age-matched wild-type pancreatic sections. Remarkably, whereas DNA damage induction of p53-p21 and senescence is beneficial in the developing lymphocytes to suppress genomic instability and prevent tumorigenesis, senescence in the pancreatic β-cells actually halts cell proliferation, leading to a depletion of islets and insulin insufficiency, resulting in diabetes.

DISCUSSION

Our study presents a unique animal model in which accumulating DNA damage, due to a deficiency of end-joining, leads to upregulation of p53-p21 and senescence in pancreatic β-cells. This p53 activity diminishes the self-replication capability of β-cells, resulting in a severe loss of the pancreatic islet number and diabetes. Our animal model further emphasizes the importance of cell replication in already differentiated β-cells for the homeostasis of islet mass and glucose metabolism. This is also a unique animal model that implicates the accumulation of DNA damage due to impaired DNA repair, a typical phenotype of aging, leading to the onset of diabetes. Therefore, this is significant for our understanding of diabetogenesis and offers potential insight into future therapies.

Diabetes occurs when β-cells fail to produce enough insulin for metabolic demands due to their dysfunction or just simply failure to maintain the islet cell mass (14,31). In adult mice, this β-cell mass is maintained by self-replication rather than differentiation from stem cells or neogenesis (17,18). Therefore, factors mediating β-cell proliferation directly impact their maintenance; mice deficient for these factors have defective β-cell replication leading to a reduction in cell number and the development of diabetes. Such examples are CDK4-deficient (32,33) or Cyclin D2–deficient (18,34) mice; both models have a progressive reduction of β-cell number and gross onset of diabetes with features of hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. Conversely, overexpression of Cyclin D1 (35) or CDK4 (32) in the pancreas leads to hyperplasia of pancreatic islet cells, indicating the importance of these key molecules and highlighting the critical role of cell proliferation in the maintenance of β-cells. Our results are in line with these models. Furthermore, it appears that neonatal and adulthood β-cell maintenance is dictated by different mechanisms. While both Cyclin D2– and CDK4-deficient newborn mice have relatively normal pancreatic islets, a progressive reduction in β-cell mass occurs as the animals age. The Lig4−/−p53p/p mice have a very similar pattern of progressive development of diabetes, strongly suggesting that the reduction in β-cell proliferation leads to the decrease in β-cell numbers and results in severe diabetes.

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, the Kip and Cip family of proteins along with the INK4/ARF family, play essential roles in regulating cell proliferation (15) and therefore directly impact β-cell maintenance. Overexpression of p16INK4a (36) or p27kip1 (37) leads to a decrease in β-cell proliferation rate and reduction in β-cell mass. Conversely, p16INK4a (36), p18INK4c, or p27kip1 (38) deficiency results in pancreatic islet hyperplasia. These results indicate that these CDK inhibitors are important regulators of cell proliferation in the pancreatic β-cells. Although cell cycle inhibitor and p53 downstream target p21 is expressed in pancreatic β-cells (39,40), islets grow and function normally in p21 deficiency, suggesting that other cell cycle inhibitors may function to compensate for the absence of p21. Interestingly, p21 is upregulated in murine pancreatic islets when overexpressing potent mitogens such as hepatocyte growth factor or placental lactogene, depicting the importance of p21 in the inhibition of growth factor–driven proliferation in murine islets. Therefore, p21, although not vital for normal β-cell proliferation and function, plays an important role when β-cells are under stress. Our previous study demonstrated that in response to genetically programmed DNA damage, p53 and its downstream target p21 are critical for driving cells into cell cycle arrest and senescence in developing lymphocytes (12). In this study, the same DNA damage–responsive pathway is activated, driving β-cells into senescence. Such a strong inhibitory mechanism of cell proliferation plays a pivotal role blocking β-cell proliferation.

The maintenance of homeostasis is dependent on a fine regulation of cellular proliferation potential, and the tumor suppressor p53 plays a key role in this regulation. Our NHEJ-deficient mice are unique models to demonstrate this concept. NHEJ deficiency in the absence of p53 leads to rapid tumorigenesis in the developing lymphoid cells, due to the presence of unrepaired physiological DNA breaks in proliferating cells that lead to chromosomal translocation and oncogene activation (10,41). The hypomorphic p53R172P successfully rescued this tumorigenic process because the residual p53 activity is able to respond to physiological or other DNA damage and blocks cell proliferation to prevent genomic instability. But this potent tumor suppression mechanism comes with a price. We propose that persistent DNA damage due to NHEJ deficiency leads to p53-dependent senescence, a program that requires cells to undergo dramatic chromatin remodeling. This leads to the shutdown of DNA replication, preventing the cells from entering the cell cycle. Senescence also leads to the silencing of many genes related to cell metabolism and cell growth. This accumulative event speeds the aging process and is deleterious to those organs that require constant regeneration and renewal, such as in pancreatic islets. We propose that Lig4−/−p53p/p mice develop severe diabetes due to the incapability of β-cell proliferation and the failure to maintain the critical β-cell mass. Accumulative DNA damage and p53-induced senescence may be the main contributors to the inhibition of β-cell proliferation. However, we cannot rule out that other effects accompanying senescence, such as the silencing of critical genes required for sensing growth signals, lead to β-cell irresponsiveness. Further investigation is required to address this matter. Additionally, due to the severe reduction of β-cell number in 3-month-old and older mice there must be a mechanism to remove senescent β-cells by means other than apoptosis. In this context, autophagy may play a role to clear out senescent cells and to recycle proteins/nutrients; further investigation is currently ongoing. Similar results have been recently reported on mice deficient for the pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG), which encodes an inhibitor for separase, which regulates chromatid separation during meiosis. Interestingly, deficiency of PTTG leads to a progressive upregulation of p21 that drives pancreatic β-cells into senescence that eventually results in insulinopenic diabetes (42).

It has been hypothesized that both accumulative DNA damage and cellular response to DNA damage are potential contributing factors for aging (43). Consistent with this hypothesis, our studies on this unique animal model showed accumulation of DNA damage, and its p53-dependent responses have a profound impact on the proliferation rate and functions of pancreatic β-cells. Deficiency in DNA repair factors accelerates DNA damage accumulation. Spontaneous damage occurs frequently in pancreatic β-cells (29), and NHEJ activity is important to repair the damage and maintain the integrity of the genome. It is the mutation in DNA damage response that gradually leads to the halting of the cellular proliferation. Both accumulation of DNA damage and gene mutations may require a long process to develop and could be major causative factors of aging. Interestingly, our study highlights the importance of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 in regulating β-cell proliferation in response to genomic stress. DNA damage–induced cellular senescence may be a potent tumor suppressing mechanism, yet it also diminishes regeneration/renewal capacity of certain organs and leads to aging-related diseases, such as diabetes with depletion of pancreatic islets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported in part by NIH Grant CA-116933, the Leukemia Research Foundation, and the American Cancer Society–Bonnie Kies Lymphatic System Research Scholar grant (to C.Z.).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

We are grateful to Drs. G. Lozano and F. Alt for providing mutant mice used in this study and the M.D. Anderson histology core facility for assistance.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahaney BL, Meek K, Lees-Miller SP: Repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks by non-homologous end-joining. Biochem J 2009;417:639–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Giblin W, Kubec M, Westfield G, St Charles J, Chadde L, Kraftson S, Sekiguchi J: Impact of a hypomorphic Artemis disease allele on lymphocyte development, DNA end processing, and genome stability. J Exp Med 2009;206:893–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills KD, Ferguson DO, Essers J, Eckersdorff M, Kanaar R, Alt FW: Rad54 and DNA Ligase IV cooperate to maintain mammalian chromatid stability. Genes Dev 2004;18:1283–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li G, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Brush JW, Goff PH, Murphy MM, Franco S, Zhang Y, Zha S: Lymphocyte-specific compensation for XLF/cernunnos end-joining functions in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell 2008;31:631–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puebla-Osorio N, Zhu C: DNA damage and repair during lymphoid development: antigen receptor diversity, genomic integrity and lymphomagenesis. Immunol Res 2008;41:103–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank KM, Sharpless NE, Gao Y, Sekiguchi JM, Ferguson DO, Zhu C, Manis JP, Horner J, DePinho RA, Alt FW: DNA ligase IV deficiency in mice leads to defective neurogenesis and embryonic lethality via the p53 pathway. Mol Cell 2000;5:993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Sun Y, Frank KM, Dikkes P, Fujiwara Y, Seidl KJ, Sekiguchi JM, Rathbun GA, Swat W, Wang J, Bronson RT, Malynn BA, Bryans M, Zhu C, Chaudhuri J, Davidson L, Ferrini R, Stamato T, Orkin SH, Greenberg ME, Alt FW: A critical role for DNA end-joining proteins in both lymphogenesis and neurogenesis. Cell 1998;95:891–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank KM, Sekiguchi JM, Seidl KJ, Swat W, Rathbun GA, Cheng HL, Davidson L, Kangaloo L, Alt FW: Late embryonic lethality and impaired V(D)J recombination in mice lacking DNA ligase IV. Nature 1998;396:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Ferguson DO, Xie W, Manis JP, Sekiguchi J, Frank KM, Chaudhuri J, Horner J, DePinho RA, Alt FW: Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genomic stability and development. Nature 2000;404:897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu C, Mills KD, Ferguson DO, Lee C, Manis J, Fleming J, Gao Y, Morton CC, Alt FW: Unrepaired DNA breaks in p53-deficient cells lead to oncogenic gene amplification subsequent to translocations. Cell 2002;109:811–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G, Parant JM, Lang G, Chau P, Chavez-Reyes A, El-Naggar AK, Multani A, Chang S, Lozano G: Chromosome stability, in the absence of apoptosis, is critical for suppression of tumorigenesis in Trp53 mutant mice. Nat Genet 2004;36:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Nguyen T, Puebla-Osorio N, Pang H, Dujka ME, Zhu C: DNA damage-induced cellular senescence is sufficient to suppress tumorigenesis: a mouse model. J Exp Med 2007;204:1453–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.d'Adda di Fagagna F: Living on a break: cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8:512–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackermann AM, Gannon M: Molecular regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass development, maintenance, and expansion. J Mol Endocrinol 2007;38:193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YC, Nielsen JH: Regulation of beta cell replication. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009;297:18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meijer AJ, Codogno P: Autophagy: a sweet process in diabetes. Cell Metab 2008;8:275–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA: Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 2004;429:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgia S, Bhushan A: Beta cell replication is the primary mechanism for maintaining postnatal beta cell mass. J Clin Invest 2004;114:963–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yesil P, Lammert E: Islet dynamics: a glimpse at beta cell proliferation. Histol Histopathol 2008;23:883–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teta M, Rankin MM, Long SY, Stein GM, Kushner JA: Growth and regeneration of adult beta cells does not involve specialized progenitors. Dev Cell 2007;12:817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halvorsen TL, Beattie GM, Lopez AD, Hayek A, Levine F: Accelerated telomere shortening and senescence in human pancreatic islet cells stimulated to divide in vitro. J Endocrinol 2000;166:103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sone H, Kagawa Y: Pancreatic beta cell senescence contributes to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in high-fat diet-induced diabetic mice. Diabetologia 2005;48:58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kukreja A, Maclaren NK: Autoimmunity and diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:4371–4378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeFronzo RA: Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Neth J Med 1997;50:191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaca M, Magnan C, Kargar C: Functional pancreatic beta-cell mass: involvement in type 2 diabetes and therapeutic intervention. Diabete Metab 2009;35:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC: Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003;52:102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scaglia L, Cahill CJ, Finegood DT, Bonner-Weir S: Apoptosis participates in the remodeling of the endocrine pancreas in the neonatal rat. Endocrinology 1997;138:1736–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam SY, Lee MK, Sabapathy K: The tumour-suppressor p53 is not required for pancreatic beta cell death during diabetes and upon irradiation. J Physiol 2008;586:407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenzen S: Oxidative stress: the vulnerable beta-cell. Biochem Soc Trans 2008;36:343–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei YF, Robins P, Carter K, Caldecott K, Pappin DJ, Yu GL, Wang RP, Shell BK, Nash RA, Schär P: Molecular cloning and expression of human cDNAs encoding a novel DNA ligase IV and DNA ligase III, an enzyme active in DNA repair and recombination. Mol Cell Biol 1995;15:3206–3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masiello P: Animal models of type 2 diabetes with reduced pancreatic beta-cell mass. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2006;38:873–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rane SG, Dubus P, Mettus RV, Galbreath EJ, Boden G, Reddy EP, Barbacid M: Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat Genet 1999;22:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsutsui T, Hesabi B, Moons DS, Pandolfi PP, Hansel KS, Koff A, Kiyokawa H: Targeted disruption of CDK4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27(Kip1) activity. Mol Cell Biol 1999;19:7011–7019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushner JA, Ciemerych MA, Sicinska E, Wartschow LM, Teta M, Long SY, Sicinski P, White MF: Cyclins D2 and D1 are essential for postnatal pancreatic beta-cell growth. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:3752–3762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Gaspard JP, Mizukami Y, Li J, Graeme-Cook F, Chung DC: Overexpression of cyclin D1 in pancreatic beta-cells in vivo results in islet hyperplasia without hypoglycemia. Diabetes 2005;54:712–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE: p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature 2006;443:453–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uchida T, Nakamura T, Hashimoto N, Matsuda T, Kotani K, Sakaue H, Kido Y, Hayashi Y, Nakayama KI, White MF, Kasuga M: Deletion of Cdkn1b ameliorates hyperglycemia by maintaining compensatory hyperinsulinemia in diabetic mice. Nat Med 2005;11:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rachdi L, Balcazar N, Elghazi L, Barker DJ, Krits I, Kiyokawa H, Bernal-Mizrachi E: Differential effects of p27 in regulation of beta-cell mass during development, neonatal period, and adult life. Diabetes 2006;55:3520–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cozar-Castellano I, Weinstock M, Haught M, Velázquez-Garcia S, Sipula D, Stewart AF: Evaluation of beta-cell replication in mice transgenic for hepatocyte growth factor and placental lactogen: comprehensive characterization of the G1/S regulatory proteins reveals unique involvement of p21cip. Diabetes 2006;55:70–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cozar-Castellano I, Haught M, Stewart AF: The cell cycle inhibitory protein p21cip is not essential for maintaining beta-cell cycle arrest or beta-cell function in vivo. Diabetes 2006;55:3271–3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Difilippantonio MJ, Petersen S, Chen HT, Johnson R, Jasin M, Kanaar R, Ried T, Nussenzweig A: Evidence for replicative repair of DNA double-strand breaks leading to oncogenic translocation and gene amplification. J Exp Med 2002;196:469–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chesnokova V, Wong C, Zonis S, Gruszka A, Wawrowsky K, Ren SG, Benshlomo A, Yu R: Diminished pancreatic beta-cell mass in securin-null mice is caused by beta-cell apoptosis and senescence. Endocrinology 2009;150:2603–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campisi J, Vijg J: Does damage to DNA and other macromolecules play a role in aging? If so, how? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:175–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.