Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the proportion of the American population who would merit metformin treatment, according to recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) consensus panel recommendations to prevent or delay the development of diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Risk factors were evaluated in 1,581 Screening for Impaired Glucose Tolerance (SIGT), 2,014 Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), and 1,111 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 (NHANES 2005–2006) subjects, who were non-Hispanic white and black, without known diabetes. Criteria for consideration of metformin included the presence of both impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), with ≥1 additional diabetes risk factor: age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, family history of diabetes, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, hypertension, or A1C >6.0%.

RESULTS

Isolated IFG, isolated IGT, and IFG and IGT were found in 18.0, 7.2, and 8.2% of SIGT; 22.3, 6.4, and 9.4% of NHANES III; and 21.8, 5.0, and 9.0% of NHANES 2005–2006 subjects, respectively. In SIGT, NHANES III, and NHANES 2005–2006, criteria for metformin consideration were met in 99, 96, and 96% of those with IFG and IGT; 31, 29, and 28% of all those with IFG; and 53, 57, and 62% of all those with IGT (8.1, 9.1, and 8.7% of all subjects), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

More than 96% of individuals with both IFG and IGT are likely to meet ADA consensus criteria for consideration of metformin. Because >28% of all those with IFG met the criteria, providers should perform oral glucose tolerance tests to find concomitant IGT in all patients with IFG. To the extent that our findings are representative of the U.S. population, ∼1 in 12 adults has a combination of pre-diabetes and risk factors that may justify consideration of metformin treatment for diabetes prevention.

Diabetes is a public health epidemic (1) associated with high morbidity, mortality (1), and cost (2). Currently, an estimated 38 million Americans have the disease, nearly 40% of which is undiagnosed, and another 87 million have pre-diabetes: impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (3). Diabetes develops insidiously over several years, during which time glucose metabolism progresses slowly from normal to pre-diabetes and then more rapidly to diabetes. Based on observational and prospective studies, ∼25–40% of individuals with pre-diabetes go on to develop diabetes over 3–8 years (4–6), and there is evidence of complications in 50% of patients at the time of diagnosis of diabetes (7).

Because progression from pre-diabetes can be prevented or delayed by lifestyle change and/or medication (4–6), the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has issued a consensus statement recommending early identification and preventive treatment in high-risk individuals (8). The panel statement recommends that individuals with both IFG and IGT and one additional risk factor (age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, family history of diabetes in first-degree relative, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, or A1C >6.0%) should be considered for treatment with metformin, in addition to lifestyle modification, which includes weight loss and physical activity.

To determine what proportion of the American population presenting with either IFG or IGT would merit consideration for metformin treatment in accordance with the recent ADA recommendations, we evaluated healthy volunteers without known diabetes who were screened for diabetes/pre-diabetes by the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

In cross-sectional analyses, we evaluated the likelihood that Americans with previously unrecognized pre-diabetes would meet ADA consensus panel recommendations for consideration of metformin in addition to change in lifestyle. Criteria for consideration of metformin included the presence of both IFG and IGT, with ≥1 additional diabetes risk factor: age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, family history of diabetes, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, hypertension, or A1C >6.0%.

Between 1 December 2005 and 31 March 2008, subjects were recruited to participate in the Screening for Impaired Glucose Tolerance (SIGT) study (9), a cross-sectional study that was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board. The invitation to participate was extended to employees of the Grady Health System, Emory HealthCare, and Emory University and Morehouse Schools of Medicine as well as to members of the community. Criteria for eligibility were age ≥18 years, non-Hispanic white or black race, no prior diagnosis of diabetes, not pregnant or breast-feeding, not taking glucocorticoids, and being well enough to have worked during the previous week (without requiring actual employment). During recruitment, 4,024 individuals expressed initial interest in the study, among whom 2,111 were scheduled for first visits (selected largely on the basis of need to balance participant sex and race), 1,658 completed first visits, and 1,581 completed the protocol. All study visits were performed in the General Clinical Research Centers at Emory University Hospital and Grady Memorial Hospital. All subjects gave written informed consent before study participation.

We also evaluated subjects who took part in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (10) and the continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 (NHANES 2005–2006) (11). NHANES is a program of studies conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that include both interviews and physical examinations in a nationally representative sample to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the U.S. NHANES III was conducted between 1988 and 1994. In 1999, the survey became a continuous program examining ∼5,000 individuals each year, which includes NHANES 2005–2006.

Measurements in the SIGT study population

Demographic information was collected by self-report and included family history of diabetes in a first-degree relative, race, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, and current medication use. Height was measured with a stadiometer after shoes were removed. Weight was measured using digital scales with subjects in light clothing. Blood pressure was measured with digital manometers after subjects had been seated quietly for 5 min.

Classification of glucose tolerance was determined by a 75-g OGTT in accordance with ADA diagnostic criteria (12): normal glucose tolerance (NGT)—fasting plasma glucose (FPG) <100 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose <140 mg/dl; isolated IFG—FPG 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose <140 mg/dl; isolated IGT—FPG <100 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose 140–199 mg/dl; any IFG—FPG 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose <199 mg/dl; any IGT—FPG <126 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose 140–199 mg/dl; combined IFG and IGT—FPG 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge glucose 140–199 mg/dl; and diabetes—FPG ≥126 mg/dl or 2-h postchallenge glucose ≥200 mg/dl. Isolated IFG was further subcategorized into fasting glucose between 100 and 109 mg/dl (IFG 100–109) and fasting glucose between 110 and 125 mg/dl (IFG 110–125). All OGTTs were begun before 11:00 a.m. after an overnight fast, with blood samples drawn at baseline, 1 h, and 2 h. Blood samples were also obtained for measurement of plasma lipids and A1C. Plasma glucose samples were obtained using sodium fluoride/oxalate preservative. Plasma samples were centrifuged, separated, and frozen within 30 min. All samples were stored at −80°C until assayed. Chemical analyses were performed in the central clinical laboratory of the Grady Health System using an LX-20 analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA); A1C measurement with this system is National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program-certified.

Statistical analysis

In the NHANES III database, a subset of adults aged ≥40 years had an OGTT performed. We analyzed only those who had no known history of diabetes, had completed the OGTT in the morning before 11:00 a.m. after an overnight fast of at least 9 h, for whom the 2-h postchallenge glucose level was measured between 100 and 135 min after ingestion of the glucose load, and had a survey weight value >0. Among this subset (n = 2,833), we included only those who were non-Hispanic black or white (to match our study population) (n = 2,057).

In the NHANES 2005–2006 population, all subjects ≥12 years who were seen in the morning session were asked to have an OGTT performed. Subjects were eligible for the OGTT if they had fasted overnight for at least 9 h, reported no use of oral medications or insulin for diabetes, were not pregnant, did not have hemophilia, and did not receive cancer chemotherapy in the previous 3 weeks. All blood samples for the 2-h glucose measurement were drawn between 100 and 135 min after ingestion of the glucose load. For our analysis, we included only those who were ≥18 years, had no known history of diabetes, were non-Hispanic black or white (to match our study population), and had a survey weight value >0 (n = 1,154). Because some subjects had more than one blood pressure measurement, the average of the measurements was used for the analysis.

For the SIGT, NHANES III, and NHANES 2005–2006 subjects, age, BMI, and A1C were categorized using the cutoffs recommended by the ADA: age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and A1C >6.0% (8). Other risk factors for diabetes that were not specifically defined by the ADA were categorized according to the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome (12): presence of hypertension by history, systolic blood pressure >130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >85 mmHg, triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dl, and HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women. Given the high number of subjects in NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2006 whose reporting of the diabetes status of one or more first-degree relatives was either not known or left blank (NHANES III, n = 1,163; NHANES 2005–2006, n = 116), relatives whose diabetes status was missing or not known were assumed to not have diabetes, a method that was also implemented for the analysis of the SIGT study group. In addition, subjects with missing values for the remaining risk factors were excluded from analysis (NHANES III: 1 missing blood pressure measurement or hypertension history, 7 missing A1C values, 27 missing triglyceride values, and 35 missing HDL cholesterol values; NHANES 2005–2006: 32 missing blood pressure measurements or hypertension history, 8 missing BMI measurements, 2 missing A1C values, 4 missing triglyceride values, and 4 missing HDL values), leaving 2,014 subjects in NHANES III and 1,111 subjects in NHANES 2005–2006 to be analyzed for metformin consideration.

Means and frequencies were determined in aggregate and by subgroup analysis of the different glucose tolerance categories. All SIGT analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). All NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2006 analyses were conducted using SUDAAN statistical software (version 10) to account for the complex survey design, and all estimates were weighted (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

RESULTS

Among 1,581 volunteers who completed OGTTs in the SIGT study, average age was 48 years and BMI was 30.3 kg/m2, 42% were male, and 58% were black (Table 1). In the selected NHANES III population (n = 2,014), the average age was 55 years and BMI was 27.3 kg/m2, 47% were male, and 10% were black, and in NHANES 2005–2006 (n = 1,111), the average age was 46 years and BMI was 28.5 kg/m2, 49% were male, and 13% were black (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| SIGT | NHANES III | NHANES 2005–2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1,581 | 2,014 (weighted) | 1,111 (weighted) |

| Age (years) | 48 ± 0.3 | 55 ± 0.5 | 46 ± 1.0 |

| Male sex (%) | 42 ± 0.01 | 47 ± 1.1 | 49 ± 1.7 |

| Black (%) | 58 ± 0.01 | 10 ± 0.8 | 13 ± 2.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 ± 0.2 | 27 ± 0.2 | 28 ± 0.2 |

| A1C (%) | 5.4 ± 0.01 | 5.4 ± 0.02 | 5.3 ± 0.02 |

| Glucose tolerance categories (%) | |||

| NGT | 62.1 ± 0.01 | 54.3 ± 1.5 | 59.1 ± 3.2 |

| IFG isolated | 18.0 ± 0.01 | 22.3 ± 1.4 | 21.8 ± 1.9 |

| IGT isolated | 7.2 ± 0.007 | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.9 |

| IFG and IGT | 8.2 ± 0.007 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 9.0 ± 1.3 |

| Diabetes | 4.6 ± 0.005 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.7 |

Data are means ± SEM.

In the SIGT population, 62.1% had normal fasting glucose and NGT, 18.0% had isolated IFG, 7.2% had isolated IGT, 8.2% had both IFG and IGT, and 4.6% had diabetes, similar to the proportions in NHANES III (54.3% had NGT, 22.3% had isolated IFG, 6.4% had isolated IGT, 9.4% had both IFG and IGT, and 7.6% had diabetes) and NHANES 2005–2006 (59.1% had NGT, 21.8% had isolated IFG, 5.0% had isolated IGT, 9.0% had both IFG and IGT, and 5.2% had diabetes). All three populations had a comparable portion with either IFG or IGT (33.4% in SIGT, 38.1% NHANES III, and 35.8% in NHANES 2005–2006).

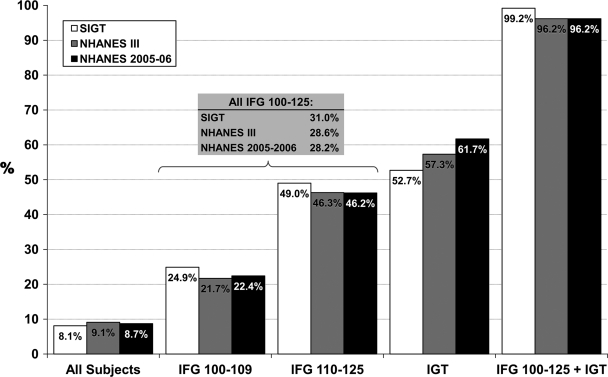

When the associated risk factors for diabetes, as specified by the ADA consensus statement (8), were considered, among those with both IFG and IGT, the presence of each risk factor was generally higher among SIGT subjects, compared with subjects in NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2006, with the exception of elevated triglycerides and A1C levels (Table 2). Even with the differences in the prevalence of risk factors, almost all subjects with both IFG and IGT in all three populations had at least one risk factor (99% in SIGT, 96% in NHANES III, and 96% in NHANES 2005–2006), which was similar among those with IFG (isolated or with IGT: 99% in SIGT, 96% in NHANES III, and 83% in NHANES 2005–2006) and those with IGT (isolated or with IFG: 99% in SIGT, 96% in NHANES III, and 94% in NHANES 2005–2006). Among all subjects with IFG (isolated or with IGT), one-quarter to one-third (31% in SIGT, 29% in NHANES III, and 28% in NHANES 2005–2006) met the recommended criteria for metformin treatment, and among all subjects with IGT (isolated or with IFG), one-half to two-thirds (53% in SIGT, 57% in NHANES III, and 62% in NHANES 2005–2006) did so (Fig. 1). Overall, ∼1 in 12 individuals in these populations met the criteria for consideration of metformin (8.1% in SIGT, 9.1% in NHANES III, and 8.7% in NHANES 2005–2006).

Table 2.

Prevalence of risk factors for diabetes in study subjects

| SIGT |

NHANES III |

NHANES 2005–2006 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | IFG (±IGT) | IGT (±IFG) | IFG + IGT | All subjects | IFG (±IGT) | IGT (±IFG) | IFG + IGT | All subjects | IFG (±IGT) | IGT (±IFG) | IFG + IGT | |

| n | 1,581 | 2,014 (weighted) | 1,111 (weighted) | |||||||||

| Age <60 years | 84 | 79 | 76 | 77 | 66 | 62 | 51 | 48 | 80 | 72 | 60 | 51 |

| BMI ≥35 kg/m2 | 22 | 27 | 30 | 38 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 23 | 27 | 30 |

| Family history of diabetes | 46 | 49 | 54 | 55 | 28 | 29 | 31 | 34 | 36 | 39 | 50 | 51 |

| Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl | 13 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 37 | 45 | 53 | 50 | 28 | 37 | 47 | 55 |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol* | 47 | 54 | 57 | 64 | 40 | 44 | 47 | 50 | 21 | 23 | 29 | 29 |

| Hypertension† | 49 | 63 | 68 | 69 | 41 | 44 | 57 | 54 | 28 | 37 | 42 | 49 |

| A1C <6.0% | 7 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 17 |

| ≥1 risk factor | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 95 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 74 | 83 | 94 | 96 |

| Metformin indicated‡ | 8.1 | 31.0 | 52.7 | 99.2 | 9.1 | 28.6 | 57.3 | 96.2 | 8.7 | 28.2 | 61.7 | 96.2 |

Data are %. Glucose tolerance categories: IFG (±IGT), IFG with or without IGT; IGT (±IFG), IGT with or without IFG; IFG + IGT, both IFG and IGT.

*Reduced HDL cholesterol defined as ≤40 mg/dl in men and ≤50 mg/dl in women.

†Hypertension defined by any of the following: history of hypertension, systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg.

‡Metformin indicated per the ADA consensus statement (8) criteria of the presence of both IFG and IGT and one of the following diabetes risk factors: age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, family history of diabetes, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, and A1C >6.0%. Risk factors for diabetes that were not specifically defined by the ADA were categorized according to the AHA/NHLBI diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome (12): presence of hypertension by history, systolic blood pressure >130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >85 mmHg, triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dl, and HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of metformin indication, stratified by glucose tolerance category. Metformin is indicated per the ADA consensus statement criteria of the presence of both IFG and IGT and one of the following diabetes risk factors: age <60 years, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, family history of diabetes, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, and A1C >6.0% (8). Risk factors for diabetes that were not specifically defined by the ADA were categorized according to the AHA/NHLBI diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome (12): presence of hypertension by history, systolic blood pressure >130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >85 mmHg, triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dl, and HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women. Glucose tolerance categories are as follows: IFG 100–109, FPG levels 100–109 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose <140 mg/dl; IFG 110–125, FPG 110–125 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose <140 mg/dl; all IFG, isolated IFG (FPG 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose <140 mg/dl); IGT, isolated IGT; and IFG 100–125 + IGT, all IFG and IGT.

CONCLUSIONS

In consideration of the enormous public health impact of diabetes and the evidence of benefit from pharmacological treatment for the prevention of diabetes, the ADA issued a consensus statement recommending preventive treatment in individuals at high risk of developing diabetes, defined as those with more severe pre-diabetes (both IFG and IGT as well as an additional risk factor) (8). To determine the proportion of individuals who would be targeted by such a recommendation, we examined a relatively healthy population without previously diagnosed diabetes (SIGT) and representative samples of the U.S. population (NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2006) and found that one-quarter to one-third had pre-diabetes. Among those with IFG, nearly one-third of subjects met the criteria for consideration of metformin treatment to prevent diabetes in accordance with the recent ADA consensus statement, more than one-half of all of the subjects with IGT qualified, and almost all of those with both IFG and IGT qualified. Overall, 8–9% met the recommended criteria. Assuming that our data are generalizable to the U.S. population, ∼24 million Americans might benefit from pharmacological treatment in addition to lifestyle modification.

The epidemic of diabetes and the insidious onset of its complications have prompted a call for early identification and preventive treatment of the disease. Diabetes is currently the leading cause of blindness, end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, and nontraumatic amputations in the U.S. and increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke by two- to fourfold, compared with those without diabetes (1). It is the seventh leading cause of death (1) and in 2007 cost $174 billion in both direct and indirect health care expenditures (2). In addition, the prevalence of diabetes has been on the rise in the adolescent population (13), indicating that the epidemic is likely to continue into the next generation.

Pre-diabetes, the stage preceding the development of diabetes, increases the risk for the development of diabetes, such that 25–39% of patients with IFG or IGT go on to develop diabetes over a period of 5–10 years (14,15). Moreover, pre-diabetes alone has been associated with an increased risk for the development of cardiovascular disease (16,17) and microvascular complications typically seen with diabetes (18). Given these risks, prospective studies have been conducted to identify preventive treatment. In addition to lifestyle modification, pharmacological treatment with acarbose (5), rosiglitazone (6), orlistat (19), or metformin (4) has shown efficacy in preventing or delaying the onset of diabetes in individuals with pre-diabetes. The relative risk reduction for diabetes in the pre-diabetic population was 25% over 3.3 years in patients treated with acarbose (5), 52–62% over 2–4 years with orlistat (19), 62% over 3 years with rosiglitazone (6), and 26–31% over 2.5–2.8 years with metformin (4). However, because many individuals with pre-diabetes are generally healthy, the benefit of preventive treatment must outweigh any associated side effects or additional risks, particularly because none of these medications have U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the indication of diabetes prevention. Gastrointestinal side effects are commonly associated with acarbose (5) and orlistat (19), leading to poor patient compliance, whereas an increased risk of bone loss (20), worsening or new-onset edema (21), and heart failure (22) are associated with rosiglitazone. Therefore, metformin, which has been used for many years and is both generally well tolerated and relatively safe, has become the leading candidate for preventive treatment.

In addition to the recommendations of the ADA, the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) has recently issued their consensus statement on the management of pre-diabetes (23). Similar to the ADA recommendations, the ACE statement recognizes the need for preventive treatment, beginning with lifestyle modification, but also emphasizes the importance of treating relevant comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity, and provides a looser set of criteria regarding the initiation of pharmacological treatment. Acarbose and metformin are their recommended treatments for individuals who are at high risk of developing diabetes, which include, but are not limited to, those with IFG, IGT, and/or the metabolic syndrome, worsening glycemia, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a history of gestational diabetes, or polycystic ovary syndrome. Taking into account the target populations as defined by the ADA and the ACE, >8% of Americans could benefit from pharmacological treatment to prevent or delay development of diabetes.

Use of pharmacological agents for the many Americans who may benefit from preventive treatment would incur substantial costs: at current generic rates for metformin, possibly $4/month × 12 months × 24 million Americans = $1.15 billion per year. However, several studies suggest that diabetes prevention or delay with metformin is likely to be cost-effective and/or cost-saving (24); further evaluation using a variety of cost analysis methods may be required to reach a definitive conclusion regarding the cost of preventive treatment.

To our knowledge, our findings are the first evaluation of the proportion of relatively healthy individuals who might benefit from metformin treatment for the prevention or delay of development of diabetes. However, our study has limitations. Because all SIGT subjects were recruited on a volunteer basis, there may have been a selection bias toward higher family history of diabetes and/or other risk factors for diabetes. Therefore, the SIGT population may represent a group of individuals at higher risk. However, because many SIGT subjects were recruited from university and health care settings, they may also follow healthier lifestyles, which could offset such a bias. Moreover, the proportion with diabetes or pre-diabetes in SIGT was no higher than that in NHANES III and was comparable to that in the more recent NHANES 2005–2006, both of which represent randomized, stratified samples of the American population.

The morbidity, mortality, and cost of the epidemic of diabetes have prompted a call for primary prevention of diabetes in high-risk individuals by the use of metformin in addition to lifestyle changes. To the extent that our findings are representative of the U.S. population, close to 1 in 12 American adults may meet the recommended guidelines for consideration of metformin treatment for diabetes prevention or delay. Notably, eligibility for metformin use appeared to be almost completely determined by impaired glucose metabolism alone, because 99% of the SIGT population and 96% of the NHANES populations with both IFG and IGT had at least one risk factor. Therefore, once the presence of both IFG and IGT has been established, the presence of additional risk factors could almost be assumed, and initiation of metformin should be considered. Moreover, because nearly one-third of all subjects with IFG met the criteria for metformin treatment, providers should perform OGTTs in all patients with IFG to test for the presence of IGT (or unrecognized diabetes) and thereby determine whether they merit consideration of metformin treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants DK-070715 and RR-017643 (to M.K.R.), HS-07922 and DK-066204 (to L.S.P., W.S.W., P.K., and V.V.), VA HSR&D SHP 08-144 and IIR 07-138 (to L.S.P.), K24-HL-077506, K24-HL-077506, R01-HL-68630, and R01-AG-026255 (to V.V.), and RR-00039.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 68th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Francisco, California, 6–10 June 2008.

We thank the other members of the SIGT research group: Jack Kaufman, Aisha Bobcombe, Rincy Varughese, Eileen Osinski, Jade Irving, Amy Barrera, Lennisha Pinckney, Jane Caudle, and Circe Tsui. We also appreciate the support of the Emory General Clinical Research Center and its staff.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Diabetes in the United States, 2007. Atlanta, GA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 596– 615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, Eberhardt MS, Byrd-Holt DD, Li C, Williams DE, Gregg EW, Bainbridge KE, Saydah SH, Geiss LS: Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 287– 294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM: the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393– 403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M: the STOP-NIDDM Trial Research Group. Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 2072– 2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Bosch J, Pogue J, Sheridan P, Dinccag N, Hanefeld M, Hoogwerf B, Laakso M, Mohan V, Shaw J, Zinman B, Holman RR: DREAM (Diabetes REduction Assessment with ramipril and rosiglitazone Medication) trial. Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006; 368: 1096– 1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). VIII. Study design, progress and performance. Diabetologia 1991; 34: 877– 890 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nathan DM, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA, Heine RJ, Henry RR, Pratley R, Zinman B: Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: implications for care. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 753– 759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Weintraub WS, Vaccarino V, Rhee MK, Chatterjee R, Narayan KM, Koch DD: Glucose challenge test screening for prediabetes and undiagnosed diabetes. Diabetologia 2009; 52: 1798– 1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994, NHANES III. Hyattsville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nh3data.htm Accessed 4 August 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES 2005–2006. Hyattsville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2005–2006/nhanes05_06.htm Accessed 4 August 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F: Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005; 112: 2735– 2752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P: The global spread of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 2005; 146: 693– 700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warram JH, Sigal RJ, Martin BC, Krolewski AS, Soeldner JS: Natural history of impaired glucose tolerance: follow-up at Joslin Clinic. Diabet Med 1996; 13: S40– S45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meigs JB, Muller DC, Nathan DM, Blake DR, Andres R: The natural history of progression from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Diabetes 2003; 52: 1475– 1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G, Hamsten A, Efendíc S, Rydén L, Malmberg K: Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet 2002; 359: 2140– 2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The DECODE Study Group on behalf of the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria: collaborative analysis of diagnostic criteria in Europe. Lancet 1999; 354: 617– 621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barr EL, Wong TY, Tapp RJ, Harper CA, Zimmet PZ, Atkins R, Shaw JE: Is peripheral neuropathy associated with retinopathy and albuminuria in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism? The 1999–2000 AusDiab. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1114– 1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L: XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 155– 161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grey A: Skeletal consequences of thiazolidinedione therapy. Osteoporos Int 2008; 19: 129– 137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollenberg NK: Considerations for management of fluid dynamic issues associated with thiazolidinediones. Am J Med 2003; 115( Suppl. 8A): 111S– 115S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW: Congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes given thiazolidinediones: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2007; 370: 1129– 1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American College of Endocrinology Task Force on Pre-Diabetes. American College of Endocrinology Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Pre-Diabetes in the Continuum of Hyperglycemia—When Do the Risks of Diabetes Begin? Washington, DC, American College of Endocrinology Task Force on Pre-Diabetes, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, Hicks K, Sorensen S, Zhang P, Hamman RF, Ackermann RT, Engelgau MM, Ratner RE: the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 323– 332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]