Abstract

Acute gonorrhea in women is characterized by a mucopurulent exudate that contains polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) with intracellular gonococci. Asymptomatic infections are also common. Information on the innate response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae in women is limited to studies with cultured cells, isolated immune cells, and analyses of cervicovaginal fluids. 17β-Estradiol-treated BALB/c mice can be experimentally infected with N. gonorrhoeae, and a vaginal PMN influx occurs in 50 to 80% of mice. Here, we compared the colonization loads and proinflammatory responses of BALB/c, C57BL/6 and C3H/HeN mice to N. gonorrhoeae. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were colonized at similar levels following inoculation with 106 CFU of N. gonorrhoeae. BALB/c, but not C57BL/6, mice exhibited a marked vaginal PMN influx. Tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), and keratinocyte-derived chemokine were elevated in vaginal secretions from infected BALB/c mice, but not in those from C57BL/6 mice. MIP-2 levels positively correlated with a vaginal PMN influx. In contrast to BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, C3H/HeN mice were resistant to infection, and there was no evidence of an inflammatory response. We conclude that N. gonorrhoeae causes a productive infection in BALB/c mice that is characterized by the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment of PMNs. Infection of C57BL/6 mice, in contrast, is more similar to asymptomatic infection. C3H/HeN mice are inherently resistant to N. gonorrhoeae infection, and this resistance is not due to an overwhelming inflammatory response to infection. Host genetic factors can therefore impact susceptibility and the immune response to N. gonorrhoeae.

Uncomplicated gonorrhea is most commonly an infection of the urethra in men and the cervix. The female urethra may also be infected, and rectal and pharyngeal infection can occur in either sex. The hallmark of symptomatic gonococcal infection is the presence of a purulent exudate containing numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), many of which contain intracellular gonococci. Asymptomatic infections are also common, particularly in females. Epithelial cells that line the genital mucosal surface are the first line of defense against this human-specific pathogen, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae produces a robust proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine response when incubated with cultured human vaginal, endocervical, ectocervical (12, 33), urethral (17), endometrial (3), and fallopian tube (31) tissue culture cells. Similarly, studies using the complex fallopian tube organ culture model suggest that N. gonorrhoeae induces the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (29). Signaling through cellular receptors on epithelial cells results in the activation and recruitment of phagocytic cells, including PMNs and macrophages. Primary macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells also elicit a proinflammatory response when incubated with N. gonorrhoeae (30, 34, 39). These innate immune cells further contribute to the array of proinflammatory cytokines and antimicrobial factors.

Due to the multiple cell types that contribute to the host innate response to infection, it is important that whole model systems be utilized to measure the impact of N. gonorrhoeae infection on the host immune response. Experimental urethral colonization in male volunteers with N. gonorrhoeae evokes a strong innate response that is characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines (37, 38). Similar studies with female subjects are not feasible due to the risk of complications of gonococcal infection in women. Therefore, features of the innate response to N. gonorrhoeae in the female genital tract are predicted solely from tissue culture systems and the analysis of clinical samples. It is unclear whether women elicit a cytokine response to gonococcal infection. The reason why some infections are asymptomatic is also not known. Hedges et al. (18, 19) were unable to detect local proinflammatory cytokines in cervicovaginal secretions from infected women and detected a low anti-gonococcal antibody response. Based on these observations, it was proposed that N. gonorrhoeae fails to induce host inflammatory responses or is actively immunosuppressive. This finding is in marked contrast with the robust induction of proinflammatory cytokines observed from in vitro cell lines that constitute the female genital tract. The absence of various other cell types in tissue culture cell models could influence the cytokine response to infection; alternatively, the timing of sample collection from infected subjects may also influence the data. Therefore, a systematic analysis of cytokine induction over the course of infection in a female animal model is needed.

The 17β-estradiol-treated mouse model is the only small-animal model available for studying the immune response to N. gonorrhoeae genital tract infection. While the mechanism by which estradiol promotes long-term colonization in female mice is not known, it is likely that promotion of an estrus-like state is beneficial for the gonococcus based on the fact that untreated mice can be transiently colonized with N. gonorrhoeae provided they are inoculated in the proestrus stage of the reproductive cycle (7, 46). The 17β-estradiol-treated mouse model has been a useful system for studying many aspects of gonococcal infection, including gonococcal evasion of PMN killing (43, 49) and antimicrobial peptides (23, 48), antigenic variation in vivo (41), and interactions between N. gonorrhoeae and commensal flora (32). This model is based on the use of BALB/c mice. Approximately 50 to 80% of infected BALB/c mice that are treated with a slow-release estradiol pellet exhibit a significant vaginal PMN response following inoculation with N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 based on examination of stained vaginal smears (21, 22, 43), and PMNs and macrophages are also found in vaginal and cervical tissue samples from infected mice (44). Gonococci are localized within vaginal and cervical tissue, and similar to that which occurs in humans, an insignificant and transient humoral response to N. gonorrhoeae occurs which was not protective against reinfection with the same strain (44). A recent modification of the model utilizes water-soluble estradiol to reduce the length of time that mice are exposed to nonphysiological concentrations of estradiol. A vaginal PMN influx also occurs during infection of mice treated with water-soluble estradiol, and as with pelleted mice, infection persists despite the presence of PMNs (44).

One advantage of using inbred mouse strains for studies of infectious diseases is that environmental and genetic components can be controlled. Interestingly, the susceptibility to infectious agents can often vary with the genetic background of the mouse. One example in the area of sexually transmitted infections is that genetically controlled differences in the development of infertility in inbred mouse strains following inoculation with chlamydia have been reported, with pregnancy rates following infection of C3H/HeN mice being significantly lower than those of C57BL/6 mice (10). Darville and colleagues (8) found similar results, and their data suggested that an earlier and more severe acute inflammatory response in the C57BL/6 strain may lead to earlier eradication of the infection, thus protecting the upper tract from disease. Numerous examples of vulnerability have been found for other infectious agents, including Leishmania major, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Plasmodium chabaudi, Legionella pneumophila, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (reviewed by Kramnik and Boyartchuk [27]).

In this study, we sought to characterize in greater detail the cytokine and inflammatory response to genital tract infection with N. gonorrhoeae in 17β-estradiol-treated BALB/c mice and to determine if susceptibility to colonization and the host inflammatory response to infection vary between inbred mouse strains. Our data demonstrate that BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mouse strains differ widely in their response to infection. While both BALB/c and C57BL/6 strains support colonization with the gonococcus, only the BALB/c strain appears to mount an inflammatory response. In contrast, the C3H/HeN strain appears to be resistant to colonization with the gonococcus. These data demonstrate significant divergence among inbred mouse strains in terms of susceptibility and inflammatory response to gonococcal infection, and they suggest that future studies can be designed to correlate genetic markers with the host response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 (porB1b, AHU [an auxotype for arginine, hypoxanthine, and uracil], and serum resistant) was originally isolated from a female with disseminated gonococcal infection and has been extensively tested in male volunteers (4). Frozen stocks of FA1090 bacteria were clonally passaged on solid GC agar containing Kellogg's supplement I (24) and 12 μM Fe(NO3)3 and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 7% CO2 incubator. GC agar with antibiotic selection (vancomycin, colistin, nystatin, trimethoprim sulfate, and streptomycin [VCNTS]) and heart infusion agar were used to isolate N. gonorrhoeae and facultatively anaerobic commensal flora from murine vaginal mucus as described previously (21). All media were from Difco.

Experimental infection of mice.

Female C57BL/6J (H-2b), BALB/cJ (H-2d), and C3H/HeN (H-2k) mice (4 to 6 weeks old) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, and treated with water-soluble 17β-estradiol (Sigma) to promote long-term susceptibility to N. gonorrhoeae as described previously (21). Mice were also given streptomycin sulfate and vancomycin (0.24 mg and 0.04 mg, respectively, intraperitoneally, twice daily) and trimethoprim sulfate (0.04 g/100 ml of drinking water) to inhibit the overgrowth of commensal flora that occurs under the influence of estradiol as described previously (21). Two days after the first dose of estradiol, groups of BALB/c (n = 10), C57BL/6 (n = 9) and C3H/HeN (n = 10) mice were vaginally inoculated with 1 × 106 CFU of N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 as described previously (21). Control groups consisted of mice of each background (n = 5) that were inoculated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Vaginal mucus was collected from all mice daily for 10 days with a sterile swab, and samples of undiluted and diluted swab contents were cultured on GC-VCNTS agar. The percentage of PMNs among 100 vaginal cells was determined by microscopic examination of stained vaginal smears.

RNA isolation from vaginal washes and relative real-time PCR.

Groups of estradiol-treated BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with strain FA1090 (test mice; n = 7) or PBS (control mice; n = 4) as described above. Dacron swabs were inserted into the vagina of mice on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinoculation. The swab contents were serially diluted and cultured for N. gonorrhoeae, and a sample was stained for visualization of PMNs. A second swab was collected and suspended in 100 μl of PBS and centrifuged for cytokine analysis by real-time PCR. The resultant pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of RNA-later (Ambion) reagent, and samples were stored at −80°C. The experiment was repeated three times to test reproducibility. For each experiment, total RNA was extracted from stored samples by using Qiagen mini-RNAeasy isolation kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total extracted RNA was then treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion) to eliminate contaminating DNA. cDNA was synthesized using reverse transcriptase SuperScript III RNaseH (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 ng to 1 μg of RNA treated with DNase I (DNase Free Turbo; Ambion) in a 10-μl volume was mixed with 1 μl (300 ng) of random hexamers (Invitogen) and 1 μl (10 mM) deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (Promega). This mixture was incubated at 65°C for 5 min and quickly chilled on ice. A cocktail containing 4 μl of 5× first-strand buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 1 μl of RNAseOut (Invitrogen) was then added to each tube. After a brief centrifugation, the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction mixtures were preincubated at 50°C for 2 min, before adding 1 μl of SuperScript III. cDNA synthesis was allowed to proceed at 50°C for 50 min, followed by incubation at 70°C for 15 min to inactivate the reaction. Nuclease-free water (1 μl) was added to reaction mixtures in place of Superscript for controls. A SYBR green master mix kit (ABI) was used to perform real-time PCR assays. cDNA reaction mixtures (20 μl) were diluted to a final volume of 100 μl with nuclease-free double-distilled water. Five microliters of diluted cDNA template was then subjected to PCR amplification in a 7500 sequence detector (ABI) in a total volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 μl SYBR green master mix, 1 μl of each primer (10 μM) and 5.5 μl double-distilled water. The reactions were performed according to the following parameters: 10 min at 95°C, then 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and at 60°C for 1 min. Data were analyzed using the Sequence Detector v.1.7a software (ABI). The cycle threshold (CT) was defined as the cycle number corresponding to the point at which the amplification plot of all samples is linear. We used the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT) for relative quantification of cytokine and chemokine gene expression, and constitutively expressed β-actin served as the active reference control (normalizer). The expression of genes of interest in each sample was measured by normalizing to the constitutively expressed β-actin gene. The calculation used included the difference between the CT values of the normalizer (β-actin) and the CT values of cytokines and chemokines (C&C) in individual samples, as follows: ΔCT(infected or uninfected) = CT(β-actin) − CT(C&C). The relative difference in gene expression between the infected and uninfected group on each day was determined by the difference of normalized gene expression levels, as follows: 2ΔΔCT = ΔCT(uninfected) − ΔCT(infected). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used for this analysis are shown in Table 1

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer (5′-3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| IL-1α gene | AGACCATCCAACCCAGATCA | TGACAAACTTCTGCCTGACG |

| IL-6 gene | CCGGAGAGGAGACTTCACAG | TCCACGATTTCCCAGAGAAC |

| TNF-α gene | ACGGCATGGATCTCAAAGAC | GTGGGTGAGGAGCACGTAGT |

| KC gene | GCACCCAAACCGAAGTCATA | TGGGGACACCTTTTAGCATC |

| MIP-2 gene | TCCAGAGCTTGAGTGTGACG | TTCAGGGTCAAGGCAAACTT |

| β-Actin gene | GCGCAAGTACTCTGTGTGGA | CATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCTG |

| 18 sRNA gene | CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA | GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT |

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Groups of estradiol-treated BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with strain FA1090 (test mice; n = 5) or PBS (control mice; n = 5) as described above. Dacron swabs were inserted into the vagina of mice on days 1 to 10 postinoculation. The swab contents were serially diluted and cultured for N. gonorrhoeae, and a sample was stained for visualization of PMNs. On days 1, 3, 5, and 7, vaginal mucus samples were also collected an hour after the cultures were taken by pipetting 50 μl PBS in and out of the vaginas of control and test mice 20 times. The lavage fluid was then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was frozen immediately and stored at −70°C until further analyzed. Analysis was performed with the Bio-Plex system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as described previously (5).

Statistical analysis and animal assurances.

The average durations of recovery and colonization loads over time were compared between groups by an unpaired t test and repeated measure of variance, respectively. Cytokine/chemokine levels as measured by ELISA and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) were compared by an unpaired t test. Pearson's correlation was applied to determine correlation coefficients between chemokine levels and PMN influx. GraphPad software was used for all statistical analyses. All animal experiments were conducted at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, a facility fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, under a protocol that was approved by the university's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

Inbred mouse strains differ in their ability to support vaginal colonization with N. gonorrhoeae.

Our previous studies with the 17β-estradiol-treated mouse model have relied on the use of the BALB/c strain. In order to compare the susceptibility and infection kinetics of gonococcal infection in mice of different genetic backgrounds, in two separate experiments, we intravaginally inoculated groups of 17β-estradiol-treated BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mice with 1 × 106 CFU of N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090. Mice of the same background received PBS as a control. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were similarly susceptible to experimental gonococcal infection, with 80% of mice of each strain colonized on day 3 and high numbers of gonococci recovered from the vaginas through the entire 10-day course of the experiment (Fig. 1A). In contrast, C3H/HeN mice were resistant to colonization, as evidenced by the recovery of low numbers of gonococci from only 2 of 10 mice on days 1 to 3 postinoculation. The average duration of colonization in C3H/HeN mice was significantly shorter (mean, 0.75 days; range, 0 to 3 days) than that of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (P < 0.01), from which gonococci were recovered for an average of 6.6 days and 6.25 days, respectively (range, 0 to 10 days for both mouse strains). The resistance to colonization in the C3H/HeN mice did not appear to be dose related, as they were also not susceptible to N. gonorrhoeae infection following inoculation with a 10-fold higher inoculum (1 × 107 CFU) of FA1090 bacteria (data not shown). The majority of mice had negative heart infusion agar cultures throughout the experiment; lactobacilli and a few gram-positive cocci were isolated from some of the mice, but there was no correlation between these commensal bacteria and colonization. All mouse strains responded to the estradiol, based on the presence of mostly squamous epithelial cells in stained vaginal smears from PBS control mice over the course of the 10-day experiment.

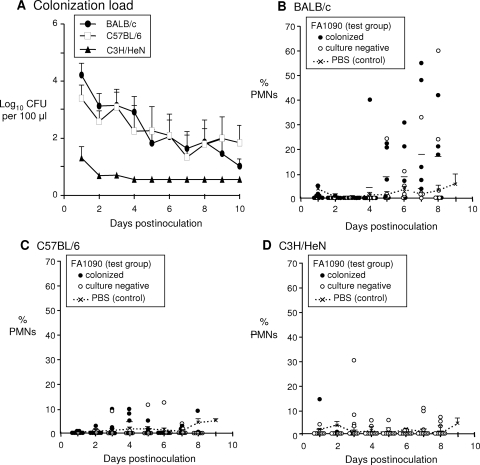

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of gonococcal infection in BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mice. Groups of BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mice (9 to 10 mice per group) were inoculated vaginally with 1 × 106 CFU of strain FA1090 as described in Materials and Methods, which is the 80% infective dose for this strain. Control mice of each background (n = 5 per group) were inoculated with PBS. (A) The average number of gonococci (log10 CFU) recovered from each group (± standard error) is shown over time. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were colonized with N. gonorrhoeae to similar levels, but C3H/HeN mice were resistant to infection. The limit of detection (4 CFU/100 μl vaginal swab suspension) was used for mice that were culture negative. (B to D) The number of PMNs among 100 vaginal cells over time. Each data point corresponds to an individual mouse, and the horizontal lines indicate the mean percentage. Solid circles indicate mice that were culture positive at that time point; open circles correspond to culture-negative mice. The average percentage of PMNs detected in vaginal smears from in PBS controls was used as a baseline and is represented by a dotted line on each graph with standard error bars shown. A marked influx of PMNs into the vagina above baseline levels was observed only in BALB/c mice.

Inbred mouse strains differ in their inflammatory response to infection.

As reported previously, N. gonorrhoeae induces a PMN influx in BALB/c mice that is detected in tissue on day 2 postinoculation and in vaginal smears on day 5 (44). Consistent with these reports, a higher percentage of PMNs was detected in vaginal smears from BALB/c mice on days 5 to 9 than that detected in those from the PBS-treated BALB/c mouse control group (Fig. 1B). Five of 10 (50%) BALB/c mice showed a PMN influx of at least 15%, which is higher than that of the average number recovered from placebo controls (Fig. 1B). Infection persisted in 4/5 mice that had a PMN influx. In contrast, only a slight increase in the percentage of PMNs was observed in stained vaginal smears from C57BL/6 test mice compared to that observed in those from PBS-treated C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1C). With the exception of one test mouse on day 1, very few samples from C3H/HeN test mice showed vaginal PMNs relative to those from PBS-treated mice of the same background (Fig. 1D). While the absence of a PMN influx in C3H/HeN mice was not surprising since they were relatively resistant to gonococcal colonization, the lack of an inflammatory response in the C57BL/6 mice was unexpected given that they had similar gonococcal colonization levels as the BALB/c mice.

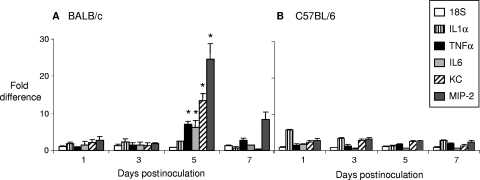

To better assess the basis for the observed difference in PMN influx in BALB/c versus C57BL/6 mice, we next used real-time RT-PCR to measure the expression kinetics of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) and chemokines (keratinocyte-derived chemokine [KC] and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 [MIP-2]) compared to those of uninfected controls in both mouse backgrounds. As shown in Fig. 2, BALB/c mice showed a slight elevation (∼2-fold) of IL-1α in response to FA1090 on days 1 through 5, which then dropped on day 7 (Fig. 2A). TNF-α and IL-6 transcript levels were increased on day 1 and day 3 (∼2-fold), peaked on day 5 (∼6- to 8-fold) and decreased on day 7 (∼2-fold). The expression patterns for chemokines KC and MIP-2 were similar to those of TNF-α and IL-6, but the peak responses of KC and MIP-2 were of a higher magnitude (∼20- to 30-fold) on day 5. C57BL/6 mice demonstrated a remarkable difference in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in response to FA1090. Expression of IL-1α, TNF-α, IL-6, KC, and MIP-2 was minimally elevated and remained constant from days 1 through 7 (Fig. 2B). There was no evidence of a peak in the expression of these cytokines/chemokines in C57BL/6 mice as was observed in BALB/c mice on day 5.

FIG. 2.

Induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in BALB/c but not C57BL/6 mice. Total RNA in vaginal washes was isolated from vaginal swabs of BALB/c (A) and C57BL/6 (B) mice on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 and reverse transcribed into cDNA. Cytokine and chemokine levels were examined by relative RT-PCR in infected samples, normalized to β-actin levels, and then compared to those of normalized uninfected samples. The difference in cytokine expression levels is shown as an n-fold increase in arbitrary units in the levels of expression of cytokines and chemokines in the infected animals over uninfected controls (± standard error of the ratios). Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were induced greatly on day 5 in BALB/c but not in C57BL/6 mice. *, P < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t test).

Vaginal MIP-2 levels correlate with vaginal PMNs.

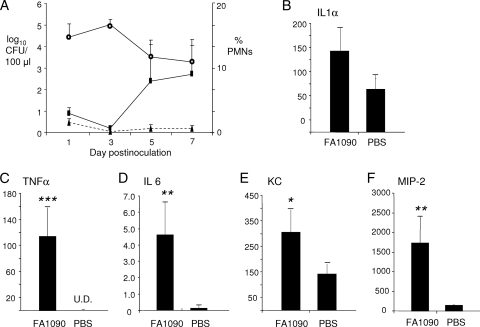

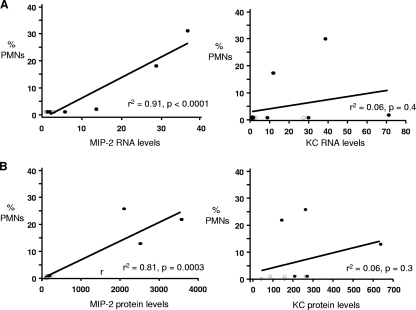

To confirm the real-time RT-PCR results, we repeated the experiment in BALB/c mice and collected vaginal wash samples on day 5 for ELISA, which, as in the RT-PCR experiments, is when a PMN influx was first observed. As before, an influx of vaginal PMNs was observed on day 5 (Fig. 3A). As with the RT-PCR results, we detected a slight elevation in IL-1α (∼2-fold) that was not statistically significant (Fig. 3B). An ∼8-fold increase in IL-6 was detected (Fig. 3D), and significant increases were also observed for TNF-α, which was detected only in the infected group (Fig. 3C), and the chemokines KC and MIP-2, which were elevated ∼2 to 3-fold and ∼10 to 15-fold, respectively (Fig. 3E and F). We conclude that N. gonorrhoeae induces a classic proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine response in BALB/c mice and that the degree of induction in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice mirrors the vaginal PMN response to N. gonorrhoeae. Interestingly, we also found that MIP-2 but not KC transcript and protein levels correlated with the degree of PMN influx in BALB/c mice. Mice that produced larger amounts of MIP-2 had larger percentages of vaginal PMNs, but a similar correlation was absent when KC expression levels were compared to the degree of PMN influx (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Confirmation of the proinflammatory cytokine response in the BALB/c mice by ELISA. In a separate experiment from that shown in Fig. 2, BALB/c mice were inoculated with N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 (test mice) or PBS (control mice) (n = 5 mice per group). Vaginal mucus was cultured for N. gonorrhoeae and stained for PMNs, and vaginal washes were collected for cytokine analysis by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. A PMN influx was observed on day 5 in test mice, and mice inoculated with strain FA1090 produced significant levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines compared to control mice. (A) The recovery of gonococci from BALB/c over time is expressed as average log10 CFU per 100 μl of vaginal swab suspension (± standard error) (open circles). PMN influx was expressed as the average number of PMNs out of 100 vaginal cells in stained smears from test mice (rectangles, solid line) and control mice (triangles, broken line). (B to F) The average concentration of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-6, and TNF-α) and chemokines (KC and MIP-2) in vaginal lavages from test and control mice. Single, double, and triple asterisks denote P values of <0.05, <0.005, and <0.0001, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Correlation between MIP-2 levels and PMN influx. The relationship between the number of PMNs and the levels of MIP-2 and KC was examined in two different experiments using Pearson's correlation. (A) The levels of MIP-2 and KC transcripts were measured on day 5 postinoculation in the test mice (closed circles; n = 7) and control mice (open circles; n = 4) used in the RT-PCR experiments shown in Fig. 2. Results are expressed as n-fold increase compared to uninfected mice. MIP-2, but not KC, production was significantly associated with an influx of vaginal PMNs (P < 0.005). (B) MIP-2 and KC protein levels were measured by ELISA in the test mice (closed circles; n = 5) and control mice (open circles; n = 5) used in the experiments shown in Fig. 3. Only MIP-2 protein levels correlated with a PMN influx in infected mice on day 5 of infection.

DISCUSSION

N. gonorrhoeae is a common sexually transmitted pathogen that is most often associated with infections of the lower genital tract. In women, the infection can be associated with acute cervicitis; however, asymptomatic infections are not uncommon. The immunological events that lead to inflammation versus asymptomatic colonization are not defined. Here, we used a mouse infection model to characterize the induction of proinflammatory cytokines during lower-genital-tract infection of a female host, and consistent with the occurrence of inflammation, we found increased levels of TNF-α, IL-6, MIP-2, and KC in infected BALB/c mice. Increased levels of MIP-2, which is the functional homologue of IL-8 in mice and has potent PMN-attracting properties (2, 25), correlated with a PMN influx into the genital tract. Initially, N. gonorrhoeae may induce proinflammatory cytokines via interactions with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2) expressed on epithelial cells, as suggested by studies with cultured human vaginal and cervical cells (11). The recruitment of other cell types to the site of infection over time may further modulate the cytokine milieu by bringing into play additional innate immune receptors as well as negative regulatory mechanisms.

In the three experiments reported here, the influx of vaginal PMNs occurred in 5/10 (50%), 3/5 (60%), and 2/7 (29%) of infected mice. This range of “responders” is consistent with previous data from our laboratory. In studies in which a placebo control group was used to measure the baseline level of vaginal PMNs, an influx of PMNs occurred in ca. 50 to 80% of infected BALB/c mice that were treated with a slow-release estradiol pellet to promote susceptibility (21, 22, 43) and in 30% to 50% of BALB/c mice that were treated with water-soluble estradiol to promote susceptibility (B. T. Mocca and A. E. Jerse, unpublished data). In our model, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were significantly increased in test mice over those in placebo controls on day 3 of infection, with a peak response at day 5, followed by a decline to basal levels by day 7. The basis for the observed kinetics is not known. Estradiol may play an immunosuppressive role in cytokine production by epithelial cells and cytokine-producing innate immune cells (reviewed extensively by Straub [45]). We utilized water-soluble estradiol in this study, which returns to physiological levels by day 3 of infection (44). Therefore, the initial delay in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines could be due to the administration of estradiol early during infection. The downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines on day 7 without the eradication of N. gonorrhoeae suggests that, at later time points, N. gonorrhoeae infection may negatively regulate inflammation. A similar pattern of localized MIP-2 and IL-6 production occurs during chlamydial genital tract infection of progesterone-treated BALB/c mice (9), suggesting that this pattern of cytokine induction may reflect a dynamic that is inherent to the immune responses of the lower female genital tract.

Cytokines were measured in test mice that were colonized for 3 to 5 days or longer. Only MIP-2 correlated with PMN influx. The detection of PMNs in vaginal smears is probably less sensitive than are other measures of inflammation, and it is possible that low numbers of PMNs or other effectors of inflammation were present in the other mice. It is not known at this time whether the increase in IL-6 in N. gonorrhoeae-infected mice, which was significant but at low concentration, is biologically significant. Continued investigation of the murine response to N. gonorrhoeae by our laboratory and others may answer these questions.

It is also not known whether phase-variable expression of gonococcal surface molecules during infection differentially triggers the innate response and thus contributes to the observed peak and subsequent decline in proinflammatory cytokines. Neither gonococcal pili nor the opacity (Opa) proteins are known to activate TLRs, and although phase variation of the glycosyltransferases genes used to build the oligosaccharide chain of gonococcal lipooligosaccharide (LOS) occurs in vivo (40), different LOS variants induce the same proinflammatory cytokines in isolated human monocytes (35). Therefore, it seems unlikely that phase variation of pili, Opa, or the carbohydrate moieties of LOS during infection are responsible for changes in cytokines over time. Perhaps a more relevant question is how phase-variable expression of surface structures might allow the gonococcus to persist during periods of high versus low induction of proinflammatory cytokines and downstream factors. Interestingly, the recovery of Opa protein-expressing gonococci from mice has a similar pattern as we observed for the induction of proinflammatory cytokines. Opa-positive variants are recovered early during infection (days 1 to 3 postinoculation), followed by a predominance of Opa-negative variants and then a return of Opa-positive variants (41). Whether this cyclical selection for Opa protein expression is driven by immunological events is not yet known.

Another important finding of our study was the demonstration of three distinct outcomes following the inoculation of estradiol-treated BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H-HeN mice with N. gonorrhoeae. C57BL/6 mice, while colonized to the same degree as were BALB/c mice, did not exhibit a marked PMN influx or significant increases in cytokine or chemokine levels in response to infection. The upregulation of chemokine secretion and the subsequent influx of PMNs are most likely driven by the innate immune system. Since there is no obvious difference between the BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice in terms of innate immunity, the explanation for this observation remains unclear. Certainly, C57BL/6 mice are capable of mounting an inflammatory cytokine and PMN response following intravaginal inoculation with Chlamydia muridarum (9), so the innate immune response of the lower genital tract would appear to be intact in both strains. Thus, the genetic basis of the observed difference in inflammation in response to N. gonorrhoeae between the two strains remains unclear. One possible explanation could be the presence of high levels of secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) in BALB/c mice, while C57BL/6 mice are genetically deficient for this enzyme (26). sPLA2 may play an important role in the generation and amplification of inflammation by the production of lipid mediators (28) and the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from immune cells (15, 47). Moreover, sPLA2 affects migration of human neutrophils in vitro (14) and could serve to explain the differential PMN influxes in these two diverse mouse backgrounds. Recently, it was reported that N. gonorrhoeae induces a T helper type 17 (Th17) response during murine infection (B. Feinen, S. L. Gaffen, A. E. Jerse, and M. W. Russell, submitted for publication), which may regulate the immune response by induction of suppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) (20). Since polarization of immune responses is known to be biased in different mouse backgrounds, an investigation of these responses in BALB/c versus C57BL/6 mice might further elucidate the basis for genetic differences in the proinflammatory response to N. gonorrhoeae.

In addition to BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, estradiol-treated SLC:ddY mice are also susceptible to infection, but in this early study, the development of a PMN influx in SLC:ddY mice cleared infection (21). Mice of the outbred strain CD1 have been successfully infected with N. gonorrhoeae for prolonged periods of time (A. E. Jerse, unpublished observation). Our demonstration that C3H/HeN mice, in contrast to these mouse strains, is resistant to N. gonorrhoeae is important in that it suggests the existence of protective host factors. The resistance shown by C3H/HeN mice was observed within 1 day postinoculation, and therefore, we hypothesize that host factors present early during infection are responsible. We found no difference in the capacity of N. gonorrhoeae to survive in serum from C3H/HeN mice versus BALB/c mice (data not shown), and thus, the possibility that antimicrobial factors in serum are responsible seems unlikely. The C3H/HeN mouse strain appears to display resistance to infection with a number of intracellular mouse pathogens, including Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (36), Leishmania donovani (1), and Mycobacterium bovis BCG (16). The genetic basis for resistance against these pathogens has been attributed to the presence of natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (Nramp1), recently renamed SLC11A1, which transports divalent metals from the phagosome and thereby limits access to essential metals, such as iron and manganese (13). Whether Nramp1 plays any role in gonococcal pathogenesis is not known. However, gonococci survive and even replicate within human PMNs (6, 42), so a role for Nramp1 during this intracellular phase is not inconceivable. While PMNs are not generally seen in vaginal smears until day 5 of infection in BALB/c mice, they were detected in tissue within 2 days after inoculation with N. gonorrhoeae (44). Finally, differences in commensal flora among the different mouse strains tested could also explain or contribute to the observed strain-dependent differences in susceptibility and host response. We found no differences in number or type of facultative anaerobic bacteria recovered from vaginal mucus during infection; however, strict anaerobes or fastidious flora would not have been isolated in this study.

In summary, these data further detail the early innate immune response to lower-genital-tract infection of female mice with N. gonorrhoeae and correlate peak PMN influx with the chemokine MIP-2. Our observation that BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mouse strains differ in their ability to support colonization with N. gonorrhoeae and mount an inflammatory response to N. gonorrhoeae in our model demonstrates a significant role for genetics in controlling host-pathogen interactions. Future comparisons between the innate response of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice may facilitate studies of the complex interactions that promote symptomatic versus asymptomatic gonococcal infections, and the observed host differences in susceptibility may lead to the identification of factors that could be exploited to protect against gonococcal infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grants RO1 AI42053 (to A.E.J.) and RO1 AI46613 (to R.R.I.).

We thank Rachel Vonck for her helpful reading of the manuscript.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradley, D. J. 1974. Letter: genetic control of natural resistance to Leishmania donovani. Nature 250:353-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacalano, G., J. Lee, K. Kikly, A. M. Ryan, S. Pitts-Meek, B. Hultgren, W. I. Wood, and M. W. Moore. 1994. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science 265:682-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christodoulides, M., J. S. Everson, B. L. Liu, P. R. Lambden, P. J. Watt, E. J. Thomas, and J. E. Heckels. 2000. Interaction of primary human endometrial cells with Neisseria gonorrhoeae expressing green fluorescent protein. Mol. Microbiol. 35:32-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen, M. S., J. G. Cannon, A. E. Jerse, L. M. Charniga, S. F. Isbey, and L. G. Whicker. 1994. Human experimentation with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: rationale, methods, and implications for the biology of infection and vaccine development. J. Infect. Dis. 169:532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cone, R. A., T. Hoen, X. Wong, R. Abusuwwa, D. J. Anderson, and T. R. Moench. 2006. Vaginal microbicides: detecting toxicities in vivo that paradoxically increase pathogen transmission. BMC Infect. Dis. 6:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criss, A. K., B. Z. Katz, and H. S. Seifert. 2009. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to non-oxidative killing by adherent human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1074-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalal, S. J., J. S. Estep, I. E. Valentin-Bon, and A. E. Jerse. 2001. Standardization of the Whitten Effect to induce susceptibility to Neisseria gonorrhoeae in female mice. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 40:13-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darville, T., C. W. Andrews, Jr., K. K. Laffoon, W. Shymasani, L. R. Kishen, and R. G. Rank. 1997. Mouse strain-dependent variation in the course and outcome of chlamydial genital tract infection is associated with differences in host response. Infect. Immun. 65:3065-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darville, T., C. W. Andrews, Jr., J. D. Sikes, P. L. Fraley, and R. G. Rank. 2001. Early local cytokine profiles in strains of mice with different outcomes from chlamydial genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 69:3556-3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Maza, L. M., S. Pal, A. Khamesipour, and E. M. Peterson. 1994. Intravaginal inoculation of mice with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar results in infertility. Infect. Immun. 62:2094-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichorova, R. N., A. O. Cronin, E. Lien, D. J. Anderson, and R. R. Ingalls. 2002. Response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae by cervicovaginal epithelial cells occurs in the absence of toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling. J. Immunol. 168:2424-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fichorova, R. N., P. J. Desai, F. C. Gibson III, and C. A. Genco. 2001. Distinct proinflammatory host responses to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 69:5840-5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes, J. R., and P. Gros. 2001. Divalent-metal transport by NRAMP proteins at the interface of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol. 9:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gambero, A., E. C. Landucci, M. H. Toyama, S. Marangoni, J. R. Giglio, H. B. Nader, C. P. Dietrich, G. De Nucci, and E. Antunes. 2002. Human neutrophil migration in vitro induced by secretory phospholipases A2: a role for cell surface glycosaminoglycans. Biochem. Pharmacol. 63:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granata, F., A. Petraroli, E. Boilard, S. Bezzine, J. Bollinger, L. Del Vecchio, M. H. Gelb, G. Lambeau, G. Marone, and M. Triggiani. 2005. Activation of cytokine production by secreted phospholipase A2 in human lung macrophages expressing the M-type receptor. J. Immunol. 174:464-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gros, P., E. Skamene, and A. Forget. 1981. Genetic control of natural resistance to Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) in mice. J. Immunol. 127:2417-2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey, H. A., D. M. Post, and M. A. Apicella. 2002. Immortalization of human urethral epithelial cells: a model for the study of the pathogenesis of and the inflammatory cytokine response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Infect. Immun. 70:5808-5815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedges, S. R., M. S. Mayo, J. Mestecky, E. W. Hook III, and M. W. Russell. 1999. Limited local and systemic antibody responses to Neisseria gonorrhoeae during uncomplicated genital infections. Infect. Immun. 67:3937-3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedges, S. R., D. A. Sibley, M. S. Mayo, E. W. Hook III, and M. W. Russell. 1998. Cytokine and antibody responses in women infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: effects of concomitant infections. J. Infect. Dis. 178:742-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imarai, M., E. Candia, C. Rodriguez-Tirado, J. Tognarelli, M. Pardo, T. Perez, D. Valdes, S. Reyes-Cerpa, P. Nelson, C. Acuna-Castillo, and K. Maisey. 2008. Regulatory T cells are locally induced during intravaginal infection of mice with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 76:5456-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerse, A. E. 1999. Experimental gonococcal genital tract infection and opacity protein expression in estradiol-treated mice. Infect. Immun. 67:5699-5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerse, A. E., E. T. Crow, A. N. Bordner, I. Rahman, C. N. Cornelissen, T. R. Moench, and K. Mehrazar. 2002. Growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the female mouse genital tract does not require the gonococcal transferrin or hemoglobin receptors and may be enhanced by commensal lactobacilli. Infect. Immun. 70:2549-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jerse, A. E., N. D. Sharma, A. N. Simms, E. T. Crow, L. A. Snyder, and W. M. Shafer. 2003. A gonococcal efflux pump system enhances bacterial survival in a female mouse model of genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 71:5576-5582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellogg, D. S., Jr., W. L. Peacock, Jr., W. E. Deacon, L. Brown, and D. I. Pirkle. 1963. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J. Bacteriol. 85:1274-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly, K. A., and R. G. Rank. 1997. Identification of homing receptors that mediate the recruitment of CD4 T cells to the genital tract following intravaginal infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 65:5198-5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy, B. P., P. Payette, J. Mudgett, P. Vadas, W. Pruzanski, M. Kwan, C. Tang, D. E. Rancourt, and W. A. Cromlish. 1995. A natural disruption of the secretory group II phospholipase A2 gene in inbred mouse strains. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22378-22385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramnik, I., and V. Boyartchuk. 2002. Immunity to intracellular pathogens as a complex genetic trait. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo, I., and M. Murakami. 2002. Phospholipase A2 enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 68-69:3-58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Maisey, K., G. Nardocci, M. Imarai, H. Cardenas, M. Rios, H. B. Croxatto, J. E. Heckels, M. Christodoulides, and L. A. Velasquez. 2003. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines and receptors by human fallopian tubes in organ culture following challenge with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 71:527-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makepeace, B. L., P. J. Watt, J. E. Heckels, and M. Christodoulides. 2001. Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with mature human macrophage opacity proteins influence production of proinflammatory cytokines. Infect. Immun. 69:1909-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales, P., P. Reyes, M. Vargas, M. Rios, M. Imarai, H. Cardenas, H. Croxatto, P. Orihuela, R. Vargas, J. Fuhrer, J. E. Heckels, M. Christodoulides, and L. Velasquez. 2006. Infection of human fallopian tube epithelial cells with Neisseria gonorrhoeae protects cells from tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 74:3643-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muench, D. F., D. J. Kuch, H. Wu, A. A. Begum, S. J. Veit, M. E. Pelletier, A. A. Soler-Garcia, and A. E. Jerse. 2009. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli inhibit gonococci in vitro but not during experimental genital tract infection. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1369-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naumann, M., S. Wessler, C. Bartsch, B. Wieland, and T. F. Meyer. 1997. Neisseria gonorrhoeae epithelial cell interaction leads to the activation of the transcription factors nuclear factor kappaB and activator protein 1 and the induction of inflammatory cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 186:247-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrone, J. B., S. E. Bish, and D. C. Stein. 2006. TNF-alpha-independent IL-8 expression: alterations in bacterial challenge dose cause differential human monocytic cytokine response. J. Immunol. 177:1314-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patrone, J. B., and D. C. Stein. 2007. Effect of gonococcal lipooligosaccharide variation on human monocytic cytokine profile. BMC Microbiol. 7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plant, J., and A. A. Glynn. 1976. Genetics of resistance to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 133:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsey, K. H., H. Schneider, A. S. Cross, J. W. Boslego, D. L. Hoover, T. L. Staley, R. A. Kuschner, and C. D. Deal. 1995. Inflammatory cytokines produced in response to experimental human gonorrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 172:186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsey, K. H., H. Schneider, R. A. Kuschner, A. F. Trofa, A. S. Cross, and C. D. Deal. 1994. Inflammatory cytokine response to experimental human infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 730:322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rarick, M., C. McPheeters, S. Bright, A. Navis, J. Skefos, P. Sebastiani, and M. Montano. 2006. Evidence for cross-regulated cytokine response in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells exposed to whole gonococcal bacteria in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 40:261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider, H., J. M. Griffiss, J. W. Boslego, P. J. Hitchcock, K. M. Zahos, and M. A. Apicella. 1991. Expression of paragloboside-like lipooligosaccharides may be a necessary component of gonococcal pathogenesis in men. J. Exp. Med. 174:1601-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simms, A. N., and A. E. Jerse. 2006. In vivo selection for Neisseria gonorrhoeae opacity protein expression in the absence of human carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecules. Infect. Immun. 74:2965-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simons, M. P., W. M. Nauseef, and M. A. Apicella. 2005. Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with adherent polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 73:1971-1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler-Garciá, A. A., and A. E. Jerse. 2007. Neisseria gonorrhoeae catalase is not required for experimental genital tract infection despite the induction of a localized neutrophil response. Infect. Immun. 75:2225-2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song, W., S. Condron, B. T. Mocca, S. J. Veit, D. Hill, A. Abbas, and A. E. Jerse. 2008. Local and humoral immune responses against primary and repeat Neisseria gonorrhoeae genital tract infections of 17beta-estradiol-treated mice. Vaccine 26:5741-5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straub, R. H. 2007. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 28:521-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streeter, P. R., and L. B. Corbeil. 1981. Gonococcal infection in endotoxin-resistant and endotoxin-susceptible mice. Infect. Immun. 32:105-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triggiani, M., F. Granata, A. Oriente, M. Gentile, A. Petraroli, B. Balestrieri, and G. Marone. 2002. Secretory Phospholipases A2 induce cytokine release from blood and synovial fluid monocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:67-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warner, D. M., W. M. Shafer, and A. E. Jerse. 2008. Clinically relevant mutations that cause derepression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump system confer different levels of antimicrobial resistance and in vivo fitness. Mol. Microbiol. 70:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, H., A. A. Soler-Garcia, and A. E. Jerse. 2009. A strain-specific catalase mutation and mutation of the metal-binding transporter gene mntC attenuate Neisseria gonorrhoeae in vivo but not by increasing susceptibility to oxidative killing by phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 77:1091-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]