Abstract

Low-copy-number plasmids generally encode a partitioning system to ensure proper segregation after replication. Little is known about partitioning of linear plasmids in Streptomyces. SLP2 is a 50-kb low-copy-number linear plasmid in Streptomyces lividans, which contains a typical parAB partitioning operon. In S. lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor, a parAB deletion resulted in moderate plasmid loss and growth retardation of colonies. The latter was caused by conjugal transfer from plasmid-containing hyphae to plasmidless hyphae. Deletion of the transfer (traB) gene eliminated conjugal transfer, lessened the growth retardation of colonies, and increased plasmid loss through sporulation cycles. The additional deletion of an intrahyphal spread gene (spd1) caused almost complete plasmid loss in a sporulation cycle and eliminated all growth retardation. Moreover, deletion of spd1 alone severely reduced conjugal transfer and stability of SLP2 in S. coelicolor M145 but had no effect on S. lividans TK64. These results revealed the following three systems for SLP2 maintenance: partitioning and spread for moving the plasmid DNA along the hyphae and into spores and conjugal transfer for rescuing plasmidless hyphae. In S. lividans, both spread and partitioning appear to overlap functionally, but in S. coelicolor, spread appears to play the main role.

Soil bacteria of the genus Streptomyces possess terminal protein (TP)-capped linear chromosomes (23) and often harbor one or more linear plasmids with similar structures (29). Like their circular counterparts, many of these linear plasmids mediate conjugation and transfer of themselves and the chromosomes (reviewed in references 12 and 13).

Conjugation in Streptomyces often produces a unique transfer-related phenotype known as “pocking” or “lethal zygosis” (4, 5). On certain solid media, transfer of a conjugative plasmid from donor to recipient leads to a growth inhibition zone (“pock”), reflecting retarded growth and development of recipient mycelia. Different plasmids display distinct pock morphology.

Streptomyces plasmids often contain only a single transfer gene (tra or kil) for mobilization of the plasmid from donor to recipient hyphae. The Streptomyces TraB proteins resemble the SpoIIIE protein of Bacillus subtilis, which translocates double-stranded chromosomal DNA during prespore formation (35). The genetic study of Possoz et al. (27) suggests that pSAM2, a circular Streptomyces plasmid, is transferred in double-stranded form. In support of this, Reuther et al. (28) showed that the TraB protein of the circular Streptomyces plasmid pSVH1 binds specifically to a 14-bp direct repeat downstream of the traB gene without any detectable nicking activity, which is required for conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA in single-stranded form via rolling circle replication.

Overexpression of the Streptomyces traB genes is lethal to the host (hence the name kil in some cases), and the presence of kil override (kor) genes is necessary for viability of the host (17). Mutations in the tra or kil gene completely abolish conjugal transfer and pocking. The mechanism of killing by traB or kil is unknown.

After the entry into the recipient mycelium, spreading of the incoming plasmid along the recipient hyphae has been proposed to rely on the plasmid-carried spread (spd) genes. The conjugative plasmids of Streptomyces usually contain two or more spd genes, which encode small hydrophobic proteins that often do not show extensive sequence similarity to one another or to other proteins in the database (9). Inactivation of a single spd gene is sufficient to cause a reduction in pock sizes (16, 19), and it was therefore postulated that the spd genes promote migration of plasmid copies inside the recipient mycelium (19).

Recently, Tiffert et al. (33) showed that overexpression of Spd2, like that of TraB, was also lethal to the host. They also demonstrated that in vitro, a spread gene product, SpdB2, formed oligomers and interacted with the TraB protein. Those authors proposed that TraB, SpdB2, and other spread proteins formed a channel at the septal cross walls for intrahyphal spread of the plasmid DNA. Involvement of TraB in spreading has also been suggested by Kataoka et al. (16), Kosono et al. (21), and Pettis and Cohen (26). This postulated involvement of Spd proteins and TraB in intrahyphal spread has, however, not yet been experimentally demonstrated.

During vegetative growth, distribution of low-copy-number plasmids in dividing bacterial cells usually involves a functional partitioning system. In Streptomyces, proper postreplicational partitioning of low-copy-number plasmids is important during the development of haploid spores from aerial hyphae to avoid plasmid loss in the subcultures, and this task is generally assumed to rely on a parAB operon, which is also used in the partitioning of many other bacterial chromosomes and plasmids (reviewed in reference 8). ParB is a DNA binding protein, which binds specifically to one or more centromere-like parS sites. ParA, a membrane-associated ATPase, is recruited by ParB to the parS site and forms a cytoskeletal structure required for the symmetric movement of the ParB-parS complex during partitioning. The involvement of conjugal transfer, spread, and partitioning in the movement of plasmids in a Streptomyces colony is depicted in Fig. 1A.

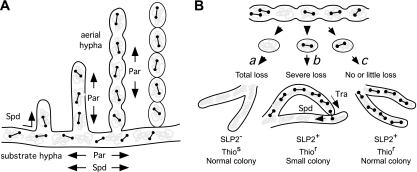

FIG. 1.

Models for partitioning, transferring, and spreading of SLP2 and their interactions in Streptomyces. (A) During vegetative growth of the mycelium, the spread of the low-copy-number plasmid SLP2 (dumbbells) along the substrate and into the aerial hyphae is aided by both the parAB partitioning system (Par) and the spread system (Spd). The proper partitioning of the plasmids into the haploid spores also involves the partitioning system. Gray blotches represent the chromosomes. (B) Involvement of conjugal transfer (Tra) and Spd systems in compensation of SLP2 loss and growth retardation caused by the ΔparAB mutation. Partitioning defect during formation of spores from aerial hyphae (top) results in the absence of SLP2tsrΔpar plasmids in some spores (path a). Colonies developed from the plasmidless spores would be of normal size and produce Thios spores. If a plasmid-containing spore suffers severe plasmid loss during colony development (path b), extensive Tra-mediated interhyphal transfer and Spd-mediated intrahyphal transfer of the plasmid (arrows) would result in acute growth retardation, and the spores produced would contain SLP2tsrΔpar and be Thior. If the plasmid suffers no or little loss during colony formation (path c), conjugal transfer and growth retardation would be minimal, and most of the spores produced would be Thior.

One or more parAB operons are found on low-copy-number plasmids in Streptomyces, the linear SLP2 plasmid in Streptomyces lividans (15), and the linear SCP1 plasmid (2) and the circular plasmid SCP2 (11) in Streptomyces coelicolor, all of which are stably maintained in their hosts. Of these, the parAB system of SCP2 has been demonstrated to be important for stable maintenance of SCP2 through sporulation cycles in S. coelicolor (11). Supposedly, the parAB system in the linear plasmids plays the same functional role.

The linear chromosome of Streptomyces also possesses a parAB operon. In S. coelicolor, about 20 parS sequences are clustered within 520 kb of oriC (3, 20). Disruption of the parAB operon on the S. coelicolor chromosome resulted in 13% of anucleate spores (20). Interestingly, this defect can be suppressed by the presence of an integrated form of the linear plasmid SCP1 (the NF state), which contains two parAB homologs (2). Other than these studies, little is known about the mechanisms of stable maintenance of low-copy-number plasmids in Streptomyces, especially the linear ones.

In this study, we initiated a study of the genetic controls of SLP2 stability. SLP2, a 50-kb linear plasmid originally identified in S. lividans 1326 (6, 15), may be conjugally transferred to and stably maintained in various other species (14). It contains 43 putative genes, including 3 involved in conjugation, spd1 (SLP2.18), traB (SLP2.19), and spd2 (SLP2.26), and a putative par operon consisting of parA (SLP2.30c) and parB (SLP2.29c) (15). We discovered that deletion of parAB (ΔparAB) causes only a mild defect in maintenance of SLP2 and surprisingly resulted in growth retardation of SLP2-containing colonies. We present evidence showing that the mild effect of the ΔparAB mutation was due to recovery of the plasmid through traB-mediated conjugal transfer from plasmid-containing to plasmidless hyphae during growth, and the growth retardation was caused by the interhyphal conjugal transfer and spd1-mediated intrahyphal spread. In addition, the intrahyphal spread function is also important for SLP2 maintenance during vegetative growth. It appears to overlap fully with the partitioning function in S. lividans (the original host) but dominates over the partitioning function in S. coelicolor, such that deletion of spd1 caused little effect on S. lividans but severely reduced the stability and conjugal transfer efficiency of SLP2 in S. coelicolor.

In contrast to unicellular bacteria, the involvement of multiple mechanisms for plasmid maintenance reflects the demand for efficient movement of plasmid DNA along the substrate and aerial hyphae before partitioning into the spores during the relatively complex life cycle of Streptomyces.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The following Streptomyces strains were used in this study: S. lividans TK64 (pro-2 str-6 SLP2− SLP3−) (14) and S. coelicolor M145 (SCP1− SCP2−) (18). Escherichia coli BW25113/pIJ790 (10) was used for the gene replacements (see below). Plasmid SLP2tsr was derived from SLP2, on which the KpnI-PstI fragment of Tn4811 was replaced by tsr (a gift from Y.-S. Lin) (Fig. 2A). Microbiological and genetic manipulations in E. coli and Streptomyces were performed as described previously (18). Throughout this study, solid medium R5 supplemented with 20 μM CuCl2 (designated R5Cu) to enhance sporulation was used for propagation of Streptomyces colonies.

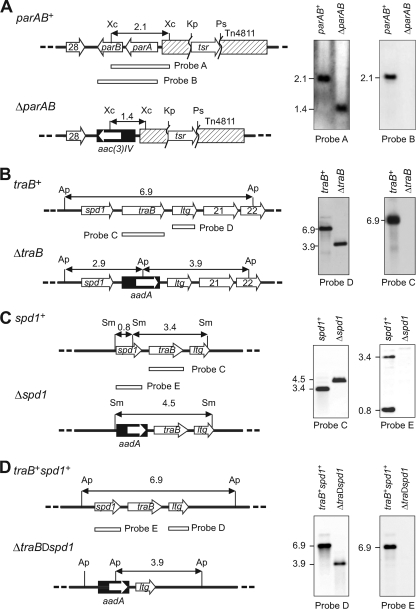

FIG. 2.

Creation of various mutations in SLP2tsr. (Left) Maps of the respective wild-type and the deletion alleles (on SLP2tsr or its derivatives) and the surrounding genes. The deleted gene(s) is replaced by a cassette (filled box) containing a resistance gene (open arrow). The extents of the hybridization probes, A to E, are indicated by the open boxes. The restriction sites (Ap, ApaLI; Kp, KpnI; Ps, PstI; Sm, SmaI; Xc, XcmI) and the expected sizes of the hybridizing fragments are indicated. (Right) Southern hybridization analyses of the mutant derivatives of SLP2tsr. Genomic DNA from strains TK64 (A, B, and C) and M145 (D) harboring SLP2tsr derivatives containing the respective wild-type or deletion mutation was digested with the restriction enzyme, separated by electrophoresis, and hybridized with the two probes as indicated. (A) ΔparAB mutation. The map shows the partial replacement of Tn4811 (truncated hashed box) by tsr on SLP2tsr. 28, SLP2.28; aac(3)IV, apramycin resistance cassette. (B) ΔtraB mutation. aadA, spectinomycin resistance cassette; ltg, putative lytic transglycosylase gene (SLP2.20); 21, SLP2.21 (hypothetical); 22, SLP2.22 (hypothetical). (C) Δspd1 mutation; (D) ΔtraB Δspd1 mutation.

Gene replacement.

The REDIRECT procedure of Gust et al. (10) was used to replace the parAB locus on a parAB-containing E. coli plasmid with a resistance marker. Primers were designed to amplify the aac(3)IV apramycin resistance cassette, and the 5′ ends were 39-bp tails matching the sequences flanking parAB. This cassette was used to transform E. coli BW25113/pIJ790 harboring a plasmid containing parAB and 2-kb flanking sequences to create a ΔparAB::aac(3)IV allele, which was subsequently used for gene replacement in Streptomyces spp. harboring an SLP2 derivative via conjugal transfer from E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (25). To confirm full disruption of the parAB genes, kanamycin-sensitive (Kms) and Aprr candidate colonies were analyzed by Southern blotting. Deletion of traB and spd1 was performed by the same method using the apramycin resistance cassette or the spectinomycin resistance cassette.

Plasmid stability analysis.

About 108 to 109 spores of cultures containing SLP2tsr and its derivatives were seeded onto a thiostrepton-containing R5Cu medium and incubated at 30°C for 14 days. Spores were collected, vortexed with glass beads for 10 min, diluted, and plated on medium with and without thiostrepton to determine the fraction of thiostrepton-resistant (Thior) spores. This sporulation cycle was repeated twice using R5Cu medium without thiostrepton to allow for loss of SLP2tsr (or its derivatives) in the absence of selection. For each colony count, at least 600 colonies were scored, representing a standard error of 4% or less.

Colony size determination.

Spores were plated on R5Cu and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. Digital photographs of the colonies were then taken, and their diameters were measured using the ruler in Canvas (version 10; Deneba) on a personal computer.

Streptomyces conjugation.

Conjugation between strain TK64 harboring SLP2tsr or its derivatives (pro donor) and M145 (pro+ recipient) was performed according to the methods of Kieser et al. (18). About 106 to 107 spores of the donor and recipient were mixed, plated on solid medium, and incubated at 30°C for 14 days. The spores produced by the mating culture were plated and counted on selective minimal medium with or without thiostrepton to score SLP2 transfer frequency. The frequency of plasmid transfer was determined by dividing the number of colonies on the thiostrepton-containing selective medium by the number of colonies on selective medium without thiostrepton.

RESULTS

The parAB operon was involved in SLP2 partitioning.

In order to evaluate its importance for SLP2 stability, the parAB operon was deleted from SLP2 (Fig. 2A). The parAB sequence on an E. coli plasmid was first replaced by an aac(3)IV cassette (conferring apramycin resistance) in E. coli, and the plasmid was conjugally transferred to S. lividans TK64 harboring SLP2tsr, which was an SLP2 derivative with a thiostrepton resistance (tsr) gene inserted in Tn4811 (Fig. 2A, left, parAB+). Apramycin-resistant transformants that contained a copy of the plasmid inserted into SLP2 through homologous recombination were isolated. Spontaneous Kms segregants, in which parAB on SLP2 had been replaced by aac(3)IV through a double crossover, were identified by Southern hybridization (Fig. 2A, right). The ΔparAB variant of SLP2tsr was designated SLP2tsrΔpar.

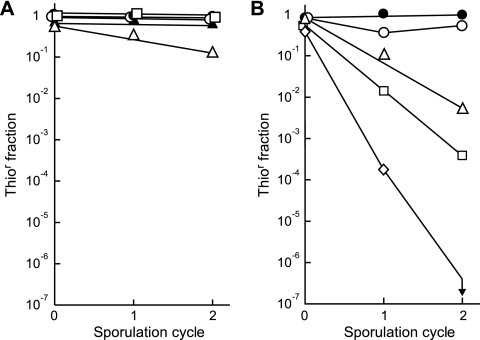

The stability of SLP2tsrΔpar in strain TK64 was examined by measuring the frequency of loss of sporulation in each cycle in the absence of thiostrepton selection. In TK64, SLP2tsrΔpar was lost in 14% of the spores after two cycles of sporulation (Fig. 3A). To repeat the test in a heterologous host, SLP2tsrΔpar was transferred to S. coelicolor M145 by conjugation, and the stability of the plasmid in this host was similarly tested (Fig. 3B). In strain M145, SLP2tsrΔpar was lost at a higher rate than in TK64—about a 50% loss in two sporulation cycles. In comparison, SLP2tsr was stably maintained in both TK64 and M145.

FIG. 3.

Stability of SLP2tsr and its derivatives. The initial spores (cycle 0) were collected from a thiostrepton-containing R5Cu medium seeded with spores collected from a colony on a thiostrepton-containing medium. In the subsequent two sporulation cycles (cycles 1 and 2), the cultures were propagated on thiostrepton-free R5Cu medium. (A) Stability in strain TK64. Filled circles, SLP2tsr; open circles, SLP2tsrΔpar; filled triangles, SLP2tsrΔtra; open triangles, SLP2tsrΔparΔtra; open squares, SLP2tsrΔspd. (B) Stability in strain M145. Filled circles, SLP2tsr; open circles, SLP2tsrΔpar; open triangles, SLP2tsrΔparΔtra; open squares, SLP2tsrΔspd; open diamonds, SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd. The vertical arrow indicates a fraction of less than 10−7 (no survival detected).

The partitioning defect caused growth retardation.

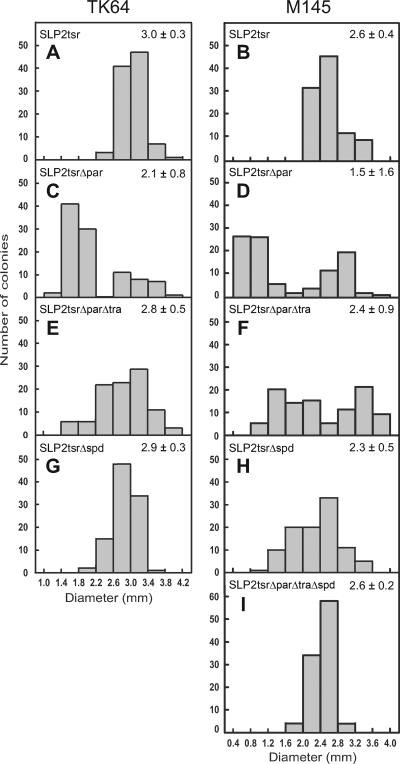

Besides causing a defect in plasmid partitioning, the ΔparAB mutation on SLP2 also conferred an unexpected phenotype on the hosts. When growing on solid medium (R5Cu) without thiostrepton selection, both TK64/SLP2tsrΔpar and M145/SLP2tsrΔpar segregated many colonies of reduced size. In the populations, there appeared to be two size classes (bimodal distribution) of colonies (Fig. 4C and D), with one class being similar to the TK64/SLP2tsr and M145/SLP2tsr colonies in size (Fig. 4A and B) and the other being about half of those or less in size. The growth retardation caused by the ΔparAB mutation was more severe in M145/SLP2tsrΔpar than in TK64/SLP2tsrΔpar (Fig. 4C and D). This is in line with the stronger effect of the ΔparAB mutation on plasmid stability in M145 than in TK64 (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 4.

Suppression of growth retardation caused by the ΔparAB mutation by the ΔtraB and Δspd1 mutations in strains TK64 (left) and M145 (right). The diameters of 100 colonies of TK64 and M145 harboring various SLP2tsr derivatives in an arbitrary area of the plates were measured and tabulated. The mean diameter (in mm) and standard deviation of each population are listed at the top right.

Examination of these colonies using the thiostrepton resistance test (backed by PCR or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analyses) showed that SLP2tsrΔpar was present in essentially all the spores from the smaller colonies but absent in significant fractions of the spores from the normal-sized colonies (20% in TK64 and 46% in M145 [Fig. 5]).

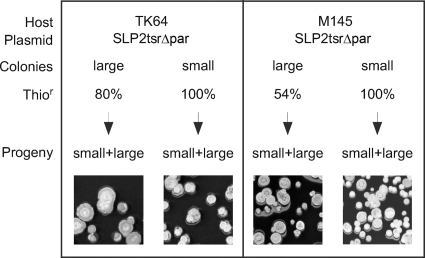

FIG. 5.

Segregation of SLP2tsrΔpar in normal and small colonies of strains TK64 and M145. Fifty small colonies and fifty normal-sized colonies of each culture were tested for thiostrepton resistance on R5Cu medium. The presence of the plasmid in the Thior colonies was confirmed by PCR in selected samples. Spores of Thior colonies derived from normal-sized and small colonies were collected and plated on nonselective medium (Progeny), and both small and normal-sized colonies were found in all cases, as exemplified in the photos.

Both the normal-sized and small colonies sporulated normally. Spores from both classes of colonies were collected and tested for segregation of small colonies. Spores from normal-sized thiostrepton-sensitive (Thios; plasmidless) colonies produced only normal-sized colonies. Spores from the Thior colonies, whether normal-sized or small, segregated both normal-sized and small colonies (Fig. 5). This indicated that the growth retardation observed in the small colonies was not a stably inherited trait but a physiological effect.

Conjugal transfer rescued the partitioning defect and caused growth retardation.

To account for the growth retardation in SLP2tsrΔpar-harboring cultures, we reasoned that if SLP2tsrΔpar was lost in some hyphae during colony growth, the plasmidless hyphae would act as recipients for plasmids transfer from nearby plasmid-containing hyphae (Fig. 1B, path b). Such conjugal transfer would cause growth inhibition (lethal zygosis) of the recipient hyphae (4, 5) and result in the reduced colony size. The fact that essentially all the spores derived from the small colonies contained SLP2tsr (Fig. 5) was consistent with this hypothetical scenario.

Under this premise, the normal-sized Thior colonies produced by SLP2tsrΔpar-harboring cultures would represent those in which SLP2tsrΔpar suffered little or no loss during colony development (Fig. 1B, path c), and the normal-sized Thios colonies would represent those developing from spores that had lost SLP2tsrΔpar in the previous round of sporulation (path a).

This model predicted that, on solid media suitable for conjugation, a defect in conjugal transfer of SLP2 would aggravate the loss of SLP2tsr and reduce the number of small colonies growing under thiostrepton selection. A putative traB gene is carried by SLP2 (15). The predicted TraB product is similar to many Tra- and SpoIIIE-like proteins and contains a typical FtsK/SpoIIIE Pfam domain. We again used the REDIRECT procedure (10) to delete traB from SLP2tsr and replace it with a copy of aac(3)IV (Fig. 2B). The resulting plasmid was designated SLP2tsrΔtra. As expected, conjugal transfer of SLP2tsrΔtra from TK64 to M145 was abolished (<10−7), while SLP2tsr was transferred at 100% efficiency (Table 1). This confirmed the essential role of traB in conjugal transfer of SLP2.

TABLE 1.

Conjugal transfer frequencies of SLP2tsr and its derivatives

| Donor (genotype) | Recipient (genotype) | Plasmid transfer frequencya |

|---|---|---|

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsr | M145 | 0.98b |

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsrΔspd | M145 | 1.38 × 10−4b |

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsr | TK54 (his-2 leu-2 spc-1) | 1.10c |

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsrΔtra | TK54 (his-2 leu-2 spc-1) | <1.53 × 10−7c |

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsrΔspd | TK54 (his-2 leu-2 spc-1) | 1.02c |

| TK64 (pro-2 str-6)/SLP2tsrΔpar | TK54 (his-2 leu-2 spc-1) | 0.83c |

Frequencies of spontaneous mutation giving rise to the recombinant type in the donors and recipients were all lower than 3 × 10−7.

Pro+ Thior colonies divided by Pro+ colonies.

Pro+ Thior Spcr colonies divided by Pro+ Spcr colonies.

Next, traB was similarly deleted from SLP2tsrΔpar in strains TK64 and M145, and the resulting plasmid was designated SLP2tsrΔparΔtra. The maintenance of SLP2tsrΔparΔtra was examined (Fig. 3). As expected from the proposed model, SLP2tsrΔparΔtra was lost at a higher rate than SLP2tsrΔpar in TK64 (Fig. 3A) and M145 (Fig. 3B). After two cycles of sporulation, about 80% of the TK64 spores and 99% of the M145 spores had lost their plasmids. In contrast, SLP2tsrΔtra was only slightly unstable in TK64, being lost at about the same frequency as SLP2tsrΔpar (10% loss after two cycles) (Fig. 3A). These results supported the predicted role of conjugal transfer in the maintenance of SLP2tsr.

The loss of SLP2tsrΔparΔtra from strain M145 was about 1 order of magnitude greater than the loss of it from TK64, whereas the stability of SLP2tsrΔpar was about the same in both strains. This indicated that conjugal transfer compensated the ΔparAB defect better in M145 than in TK64. This was consistent with the fact that the M145/SLP2tsrΔparΔtra colonies suffered more severe growth retardation than the TK64/SLP2tsrΔparΔtra colonies (Fig. 4E and F).

Deletion of spd1 had different effects on S. coelicolor and S. lividans.

Growth retardation was reduced but not eliminated in TK64/SLP2tsrΔparΔtra and M145/SLP2tsrΔparΔtra. Although the mean sizes of the colonies were significantly larger than those of TK64/SLP2tsrΔpar and M145/SLP2tsrΔpar colonies (Fig. 4C and D), a significant fraction (about 10%) of small colonies (less than 2.2 mm in diameter) was still present (Fig. 4E and F). We reasoned that the residual growth retardation observed might have been caused by intrahyphal spread mediated by the spread (spd) genes carried by SLP2, which might have exerted lethal zygosis like the spd genes in other plasmids (33).

Two spd homologues (spd1 and spd2) were present on SLP2 (15) that are similar to spdB2 and spdB3 of circular plasmid pJV1, respectively (30). Since SpdB2 (the Spd1 homolog) is the only Spd protein that has a clear homolog in all conjugative Streptomyces plasmids (33), we attempted to delete this gene. Deletion of spd1 was readily achieved on SLP2tsr in TK64 (Fig. 2C) and M145 (not shown) and resulted in SLP2tsrΔspd. Interestingly, the Δspd1 mutation conferred different effects on TK64 and M145. While SLP2tsrΔspd was as stably maintained as SLP2tsr in TK64, it was highly unstable (more unstable than SLP2tsrΔparΔtra) in M145 (Fig. 3A and B).

The result indicated that, in M145, spd1 was functional during vegetative growth and that it played a more crucial role in SLP2 maintenance than par and tra combined. This was in contrast to the situation in TK64, in which spd1 appeared to play a less important role than par and traB combined (Fig. 3A). This does not necessarily mean that spd1 was not important in TK64. It was likely that its functional role overlapped with that of parAB. This was consistent with the fact that a single deletion of either spd1 or traB had little effect on SLP2 stability.

The plasmid-destabilizing effect of the Δspd1 mutation on M145 was also reflected in the appearance of smaller colonies in M145/SLP2tsrΔspd (Fig. 4H), which presumably represented growth retardation during conjugal transfer between plasmid-containing and plasmidless hyphae. As expected, the colonies of TK64/SLP2tsrΔspd exhibited essentially no such growth retardation (Fig. 4G).

The Δspd1 mutation also exerted different effects on conjugal transfer of SLP2tsr from TK64 to TK54 and M145. Transfer of SLP2tsrΔspd to TK54 was as efficient (about 100%) as that of SLP2tsr (Table 1). In comparison, transfer of SLP2tsrΔspd from TK64 to M145 was slower (1.38 × 10−4) than that of SLP2tsr (about 100%) by 4 orders of magnitude. This was expected, because plasmid transfer in Streptomyces was scored in spores collected from the mating mycelia, and the severe effect of the Δspd1 defect on intrahyphal transfer in the M145 recipient was expected to result in a deficiency of SLP2 in the aerial hyphae and the spores developed from them. That the Δspd1 mutation exerted no effect on SLP2 transfer from TK64 to TK54 was also consistent with the lack of effect on SLP2 maintenance in TK64 during vegetative growth. The Δspd1 defect was presumably compensated by the partitioning system of SLP2 in TK64 but not in M145. This implied that the partitioning system of SLP2 was insufficiently expressed in M145.

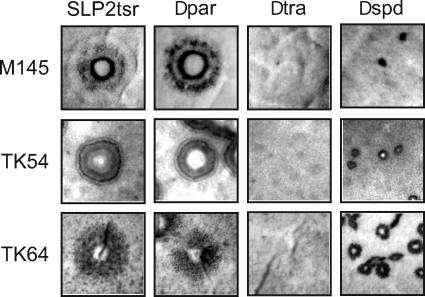

The effects of the Δspd1 mutation on pock size were examined. When TK64/SLP2tsrΔspd was plated on lawns of plasmidless recipients TK54 and M145, the pocks produced were significantly smaller than those produced by TK64/SLP2tsr or TK64/SLP2tsrΔpar (Fig. 6). As expected, in both matings, the ΔparAB mutation did not affect the pock size, and the ΔtraB mutation eliminated pock formation. These results confirmed the effect caused by the mutation in a spread gene on the pock sizes, as observed with circular plasmids (16, 19).

FIG. 6.

Pocks caused by conjugal transfer of SLP2tsr and its variants. Serial dilutions of spores of TK64 harboring SLP2tsr or its variants (-Δpar, -Δtra, and -Δspd) were made and spotted on R5 medium seeded with about 108 spores of M145 (top), TK54 (middle), or TK64 (bottom). The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 to 4 days. Pocks formed around single-donor colonies were photographed. Note that no pocks were visible in the SLP2tsrΔtra samples.

The triple mutant SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd was extremely unstable in S. coelicolor.

To create triple mutations in parAB, traB, and spd1, an attempt was made to delete the neighboring spd1 and traB genes together from SLP2tsrΔpar (Fig. 2D). This proved to be extremely difficult. Although transformants, in which the knockout plasmid was integrated by a single crossover, were readily isolated, only one double-crossover transformant (resulting in a deletion of spd1 and traB) was isolated in M145 (but not in TK64) after screening about 6,000 independent transformants. The deletion of spd1 and traB on SLP2tsrΔpar was confirmed by Southern hybridization (Fig. 2D), and this SLP2 derivative was designated SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd.

Attempts to create the triple mutations by deleting spd1 and traB from SLP2tsrΔpar in TK64 were not successful after screening more than 2,000 transformants. Transfer of SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd from M145 to TK64 by conjugation or transformation also failed.

Colonies of M145/SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd exhibited a size distribution similar to that of M145/SLP2tsr (Fig. 5H), i.e., essentially without small colonies. In this culture, SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd displayed a dramatic instability. Even in the presence of thiostrepton selection during a sporulation cycle, about 34% of the spores had lost the plasmid (cycle 0) (Fig. 3B). After another round of sporulation without the selection (cycle 1), only about 0.02% of the spores had retained the plasmid, and after another sporulation cycle without selection (cycle 2), no plasmid-harboring spore was detected (<10−7). These results suggested that the partitioning (par), transfer (traB), and spread (spd1) systems constitute the major components in the maintenance of SLP2 in M145.

DISCUSSION

Nordström and Austin (24) pointed out the following three common mechanisms that act to maintain stably low-copy-number plasmids in bacteria: (i) partitioning systems that accurately partition sister replicons into daughter cells during division; (ii) toxin-antidote systems that kill bacteria that have lost the plasmid; and (iii) efficient site-specific recombination systems that resolve multimers, which are generated by homologous recombination, into monomers. In Streptomyces, the first strategy is common in circular and linear low-copy-number plasmids, as is evident from the presence of one or more parAB operons on these plasmids. The functionality of this system has previously been demonstrated for a circular Streptomyces plasmid, SCP2 (11), and is shown here for a linear plasmid, SLP2. The second strategy has not been found in Streptomyces so far. The third strategy was identified in the circular plasmid SCP2 and found to play a major role in stabilization (11) but has not been found in SLP2 or other linear plasmids, probably because homologous recombination between linear replicons does not generate multimers that require active enzymatic resolution.

In this paper, we identified two additional SLP2-encoded genes, traB and spd1, that are also involved in SLP2 stabilization. While traB assumes a rescue role by mediating conjugal transfer that introduces the plasmid into hypha segments that have lost the plasmid during growth, spd1 appears to assist the intramycelial movement of the plasmid during vegetative growth and during conjugal transfer. In the absence of the partitioning, transfer, and spread systems, the plasmid (SLP2tsrΔparΔtraΔspd) was almost completely lost after a sporulation cycle in S. coelicolor. Although we could not create such a triple mutation in SLP2tsr in S. lividans, the mini-SLP2 plasmids created by Xu et al. (36), which contained only the basic replication locus of SLP2, were also highly unstable in S. lividans (about 99% loss), supporting the importance of the three systems in SLP2 maintenance.

The spread and partitioning systems are both involved in postreplicative movement of the plasmid DNA along the hyphae (Fig. 1A) and thus appear to overlap in cellular functions. We propose that, in TK64, the functional overlap between the spread and partitioning systems is extensive, such that a defect in either system resulted in relatively moderate instability. The Δspd1 mutation causes no SLP2 instability, while the Δpar mutation resulted in about 14% loss of SLP2tsr in two sporulation cycle in TK64. The latter presumably reflects the lack of proper partition during the spore formation, a function that cannot be substituted by the spread system. In M145, the spread system appears to be significantly more important than the partitioning system in intrahyphal spreading, such that the Δspd1 mutation resulted in a more severe effect than the Δpar mutation.

It is not clear why the partitioning system of SLP2 is relatively weaker in M145 than in TK64. This may be attributed to the fact that S. lividans (of which TK64 is a derivative) is the original natural host of SLP2 (14), and SLP2 probably has developed robust and aggressive stabilization systems to minimize loss in S. lividans through evolution. For example, the expression of the parAB operon may be more efficiently and precisely regulated in S. lividans than in S. coelicolor.

The relatively small effect of the single Δpar and Δspd1 mutations on TK64 might also be attributed to the existence in S. lividans (but not in S. coelicolor) of an unidentified system that complements these defects. However, we think that this is unlikely, considering our failure to create Δpar ΔtraB Δspd1 triple mutations in SLP2tsr in TK64. In the presence of a complementing system, such a triple mutation should be readily created.

The involvement of spd1 in vegetative maintenance of SLP2 is surprising, because the spd genes were previously assumed to act only during conjugal transfer (16, 19). The fact that, in one sporulation cycle of the M145/SLP2tsrΔspd culture, the plasmid is lost from more than 99% of the spores (Fig. 3B) indicates that the defect has severely deprived the aerial mycelia of the plasmid, such that most spores formed are plasmidless. This indicates that spd1 is important in moving the plasmid DNA into aerial mycelia during vegetative growth of M145 (Fig. 1A). In this regard, it is noteworthy that the Orfgp25 early gene of φC31 phage of Streptomyces is an spd homolog, which supposedly functions in spreading the phage DNA within the Streptomyces hyphae, resulting in a more efficient infection (32).

The involvement of spd1 in conjugal transfer is also demonstrated in M145. The frequency of transfer of SLP2tsrΔspd (scored by the presence of the plasmid in the recipient spores) was about 4 orders of magnitude higher than that of SLP2tsr (Table 1). The same plasmid was transferred to TK54 at a frequency of about 100%. The clear distinction between the Δspd1 effects on S. coelicolor and those on S. lividans further supports our postulation that the partitioning system of SLP2 in S. lividans is functionally adequate to compensate for a defective spread system but not so in S. coelicolor.

Typically, two to six spd genes are present on a conjugative plasmid and often form one or two operons with translational coupling. Some of them are very small (50- to 90-amino-acid) hydrophobic proteins and are not similar to other Spd proteins. Most of the larger Spd proteins contain three to four transmembrane helices (33). No specific motifs or signatures are present in the Spd proteins, except for a Pfam TolA domain found in SpdB2SL of pSLS and SpdB2 of pJV1 (33). TolA is involved in the uptake of colicins and single-stranded DNA (7, 34). Grohmann et al. (9) speculated that the Spd proteins may interact to form a cross wall-traversing complex to support translocation of the plasmid DNA to the neighboring mycelial compartments. Recently, Tiffert et al. (33) showed that SpdB2 of the pSVH1 plasmid (Spd1 homolog) is an oligomeric integral membrane protein that binds to double-stranded DNA nonspecifically and to the transfer protein TraB, which recognize the clt (cis-acting locus of transfer) locus of pSVH1 DNA (28). They proposed that plasmid DNA moves through a membrane-traversing channel formed by oligomeric SpdB2 and other Spd proteins at the septal cross walls and that TraB interacts with this complex to pump the plasmid DNA through the channel into the neighboring hyphal compartment.

There exists discord regarding the proposed role of traB in intrahyphal spread in the model shown by Tiffert et al. (33) and in our results. In our genetic analysis, a single Δspd1 mutation caused severe instability of SLP2, whereas a single ΔtraB mutation caused little instability in TK64. Based on the model shown by Tiffert et al., in which Spd2 and TraB work together to perform intrahyphal spread, a deletion of either spd2 or traB would exert a similar instability of SLP2. If anything, the ΔtraB mutation would cause more severe instability than Δspd1, because traB is also involved in plasmid rescue. We cannot offer any simple explanation for the discord except to point out that the plasmid they studied was circular and the plasmid we studied was linear.

The main role of the transfer function (traB) of SLP2 in plasmid maintenance appears to be that of a rescuer. If the partitioning system is intact in SLP2, the effect of ΔtraB on plasmid stability was insignificant (Fig. 3A). In E. coli, conjugal transfer has also been shown to be involved in stable maintenance of low-copy-number plasmid RK2 (31). In this case, defect in conjugal transfer (caused by a mutation in traJ or traG) resulted in plasmid loss in colonies growing on solid medium (where conjugation is favored). The contribution of conjugal transfer to maintenance of plasmid pKJK5 in E. coli has also been demonstrated in gastrointestinal tracts of rats (1). More recently, a study by Lin and Liu (22) showed that a Pantoea stewartii plasmid, pSW100, is stabilized by the F conjugation system in E. coli. Those authors showed that mutations in genes encoding the sex pilus reduced plasmid stability and hypothesized that pSW100 might use sex pilus assembly as a partitioning apparatus to maintain stability. An alternative explanation would be that the lost pSW100 is regained by conjugal transfer, as proposed here for SLP2.

The involvement of conjugal transfer and spread function in the SLP2 maintenance and colony growth retardation observed here might also be true for some other linear and circular plasmids. In the previous study of the circular plasmid SCP2 (11), the plasmid constructs used to test the parAB operon did not contain tra, and therefore, any possible interplay between the two systems would not have been observed. The participation of transfer and spread in maintenance may not play a significant role for high-copy-number plasmids. For one such plasmid pIJ101, derivatives lacking the spd genes are stably maintained (19).

Retrospectively, the involvement of traB and spd in plasmid maintenance was explicable, when one considers the nature of the development of Streptomyces colonies. In contrast to unicellular bacteria, the filamentous Streptomyces require the replicated plasmid to be distributed along the substrate hyphae and across the branch junctions into the aerial mycelia, where they are properly partitioned into haploid spores. The intrahyphal movement of plasmid DNA is more important than the partitioning system for stable maintenance of plasmid. A defect in intrahyphal movement of plasmid DNA can readily deplete the aerial hyphae of the plasmid DNA and resulted in all plasmidless spores. In comparison, a defective partitioning system would result maximally in 25% of plasmidless spores for a single-copy plasmid and exponentially less for plasmids with a high copy number.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tobias Kieser and David Hopwood for critical reading of the manuscript and Günther Muth for helpful discussions.

This study was funded by research grants from the National Science Council, ROC (grants NSC95-2321-B-010-002 and NSC96-2321-B-010-001), and a grant (Aim for the Top University Plan) from the Ministry of Education, ROC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahl, M. I., L. H. Hansen, T. R. Licht, and S. J. Sorensen. 2007. Conjugative transfer facilitates stable maintenance of IncP-1 plasmid pKJK5 in Escherichia coli cells colonizing the gastrointestinal tract of the germfree rat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:341-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley, S. D., S. Brown, L. D. Murphy, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, J. Parkhill, B. G. Barrell, J. R. McCormick, R. I. Santamaria, R. Losick, M. Yamasaki, H. Kinashi, C. W. Chen, G. Chandra, D. Jakimowicz, H. M. Kieser, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2004. SCP1, a 356,023 base pair linear plasmid adapted to the ecology and developmental biology of its host, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 51:1615-1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A.-M. Cerdeño-Tárraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibb, M. J., and D. A. Hopwood. 1981. Genetic studies of the fertility plasmid SCP2 and its SCP2* variants in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Gen. Microbiol. 126:427-442. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibb, M. J., J. M. Ward, and D. A. Hopwood. 1978. Transformation of plasmid DNA into Streptomyces at high frequency. Nature 274:398-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, C. W., T.-W. Yu, Y. S. Lin, H. M. Kieser, and D. A. Hopwood. 1993. The conjugative plasmid SLP2 of Streptomyces lividans is a 50 kb linear molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 7:925-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Click, E. M., and R. E. Webster. 1998. The TolQRA proteins are required for membrane insertion of the major capsid protein of the filamentous phage f1 during infection. J. Bacteriol. 180:1723-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh, S. K., S. Hajra, A. Paek, and M. Jayaram. 2006. Mechanisms for chromosome and plasmid segregation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:211-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grohmann, E., G. Muth, and M. Espinosa. 2003. Conjugative plasmid transfer in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:277-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haug, I., A. Weissenborn, D. Brolle, S. Bentley, T. Kieser, and J. Altenbuchner. 2003. Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) plasmid SCP2*: deductions from the complete sequence. Microbiology 149:505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopwood, D. A. 2006. Soil to genomics: the Streptomyces chromosome. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopwood, D. A., and T. Kieser. 1993. Conjugative plasmids of Streptomyces, p. 293-311. In D. B. Clewell (ed.), Bacterial conjugation. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 14.Hopwood, D. A., T. Kieser, H. M. Wright, and M. J. Bibb. 1983. Plasmids, recombination, and chromosomal mapping in Streptomyces lividans 66. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:2257-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, C. H., C. Y. Chen, H. H. Tsai, C. Chen, Y. S. Lin, and C. W. Chen. 2003. Linear plasmid SLP2 of Streptomyces lividans is a composite replicon. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1563-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kataoka, M., Y. M. Kiyose, Y. Michisuji, T. Horiguchi, T. Seki, and T. Yoshida. 1994. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Streptomyces nigrifaciens plasmid, pSN22: genetic organization and correlation with genetic properties. Plasmid 32:55-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendall, K. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1987. Plasmid transfer in Streptomyces lividans: identification of a kil-kor system associated with the transfer region of pIJ101. J. Bacteriol. 169:4177-4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieser, T., M. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 19.Kieser, T., D. A. Hopwood, H. M. Wright, and C. J. Thompson. 1982. pIJ101, a multi-copy broad host-range Streptomyces plasmid: functional analysis and development of DNA cloning vectors. Mol. Gen. Genet. 185:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, H. J., M. J. Calcutt, F. J. Schmidt, and K. F. Chater. 2000. Partitioning of the linear chromosome during sporulation of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) involves an oriC-linked parAB locus. J. Bacteriol. 182:1313-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosono, S., M. Kataoka, T. Seki, and T. Yoshida. 1996. The TraB protein, which mediates the intermycelial transfer of the Streptomyces plasmid pSN22, has functional NTP-binding motifs and is localized to the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 19:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, M. H., and S. T. Liu. 2008. Stabilization of pSW100 from Pantoea stewartii by the F conjugation system. J. Bacteriol. 190:3681-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin, Y.-S., H. M. Kieser, D. A. Hopwood, and C. W. Chen. 1993. The chromosomal DNA of Streptomyces lividans 66 is linear. Mol. Microbiol. 10:923-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordström, K., and S. J. Austin. 1989. Mechanisms that contribute to the stable segregation of plasmids. Annu. Rev. Genet. 23:37-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paget, M. S., L. Chamberlin, A. Atrih, S. J. Foster, and M. J. Buttner. 1999. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor sigmaE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 181:204-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pettis, G. S., and S. N. Cohen. 2000. Mutational analysis of the tra locus of the broad-host-range Streptomyces plasmid pIJ101. J. Bacteriol. 182:4500-4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Possoz, C., C. Ribard, J. Gagnat, J. L. Pernodet, and M. Guerineau. 2001. The integrative element pSAM2 from Streptomyces: kinetics and mode of conjugal transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 42:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reuther, J., C. Gekeler, Y. Tiffert, W. Wohlleben, and G. Muth. 2006. Unique conjugation mechanism in mycelial streptomycetes: a DNA-binding ATPase translocates unprocessed plasmid DNA at the hyphal tip. Mol. Microbiol. 61:436-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakaguchi, K. 1990. Invertrons, a class of structurally and functionally related genetic elements that include linear plasmids, transposable elements, and genomes of adeno-type viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 54:66-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Servin-Gonzalez, L., A. I. Sampieri, J. Cabello, L. Galvan, V. Juarez, and C. Castro. 1995. Sequence and functional analysis of the Streptomyces phaeochromogenes plasmid pJV1 reveals a modular organization of Streptomyces plasmids that replicate by rolling circle. Microbiology 141:2499-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sia, E. A., R. C. Roberts, C. Easter, D. R. Helinski, and D. H. Figurski. 1995. Different relative importances of the par operons and the effect of conjugal transfer on the maintenance of intact promiscuous plasmid RK2. J. Bacteriol. 177:2789-2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, M. C., R. N. Burns, S. E. Wilson, and M. A. Gregory. 1999. The complete genome sequence of the Streptomyces temperate phage straight φC31: evolutionary relationships to other viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:2145-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiffert, Y., B. Gotz, J. Reuther, W. Wohlleben, and G. Muth. 2007. Conjugative DNA transfer in Streptomyces: SpdB2 involved in the intramycelial spreading of plasmid pSVH1 is an oligomeric integral membrane protein that binds to dsDNA. Microbiology 153:2976-2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster, R. E. 1991. The tol gene products and the import of macromolecules into Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1005-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, L. J., P. J. Lewis, R. Allmansberger, P. M. Hauser, and J. Errington. 1995. A conjugation-like mechanism for prespore chromosome partitioning during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 9:1316-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu, M., Y. Zhu, R. Zhang, M. Shen, W. Jiang, G. Zhao, and Z. Qin. 2006. Characterization of the genetic components of Streptomyces lividans linear plasmid SLP2 for replication in circular and linear modes. J. Bacteriol. 188:6851-6857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]