Abstract

The mismatch correction (MMC) system repairs DNA mismatches and single nucleotide insertions or deletions postreplication. To test the functions of MMC in the obligate human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae, homologues of the core MMC genes mutS and mutL were inactivated in strain FA1090. No mutH homologue was found in the FA1090 genome, suggesting that gonococcal MMC is not methyl directed. MMC mutants were compared to a mutant in uvrD, the helicase that functions with MMC in Escherichia coli. Inactivation of MMC or uvrD increased spontaneous resistance to rifampin and nalidixic acid, and MMC/uvrD double mutants exhibited higher mutation frequencies than any single mutant. Loss of MMC marginally enhanced the transformation efficiency of DNA carrying a single nucleotide mismatch but not that of DNA with a 1-kb insertion. Unlike the exquisite UV sensitivity of the uvrD mutant, inactivating MMC did not affect survival after UV irradiation. MMC and uvrD mutants exhibited increased PilC-dependent pilus phase variation. mutS-deficient gonococci underwent an increased frequency of pilin antigenic variation, whereas uvrD had no effect. Recombination tracts in the mutS pilin variants were longer than in parental gonococci but utilized the same donor pilS loci. These results show that gonococcal MMC repairs mismatches and small insertion/deletions in DNA and also affects the recombination events underlying pilin antigenic variation. The differential effects of MMC and uvrD in gonococci unexpectedly reveal that MMC can function independently of uvrD in this human-specific pathogen.

Mismatch correction (MMC) is a system conserved in prokaryotes and eukaryotes that repairs base pair mismatches and small insertion-deletion loops which arise following DNA replication or as a consequence of recombination (23, 41). MMC is a stepwise process involving a conserved set of proteins that recognize the mismatch, remove it from the nontemplate strand of DNA, and repair the lesion to the parental sequence. In Escherichia coli, which harbors the best-understood bacterial MMC system, mismatch recognition is mediated by the ATPase MutS. Another ATPase, MutL, stabilizes the MutS-mismatch complex and recruits the endonuclease MutH, which selectively nicks the nontemplate strand of DNA at hemi-methylated 5′-GATC-3′ sequences. The UvrD (MutU) helicase unwinds the DNA strands, exonucleases remove the mismatch-containing DNA, DNA polymerase III fills in the gapped region, and DNA ligase seals the repaired DNA. In contrast to E. coli, many bacterial species lack MutH homologues. In this situation, the mismatch-containing nontemplate strand may be distinguished by the presence of Okazaki fragments (as discussed in reference 23), and endonuclease activity may be provided by MutL, whose latent nicking activity is activated in a MutS- and DNA polymerase subunit-dependent manner (17).

Inactivation of mutS, mutL, mutH, and uvrD yields mutator strains of bacteria, which can be detected by increased frequencies of mutations that confer resistance to certain antibiotics (e.g., nalidixic acid, rifampin, or spectinomycin) (3). Mutator strains also undergo higher frequencies of phase variation due to slipped strand mispairing at mononucleotide tracts in the coding or promoter regions of the phase-variable gene (25). In addition, mutator strains can exhibit increased homeologous recombination, or the ability to recombine foreign DNA with reduced homology with the resident sequences during genetic transfer (15, 36, 58). Although an increased mutation rate can result in fitness costs to an individual organism, mutator strains may be valuable on a population level because they serve as a source of mutated genes to aid adaptation to changing host or environmental conditions (41).

Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonococci [Gc]) are obligate human pathogens that undergo extensive phase and antigenic variation, processes that often aid the bacteria in immune evasion and adaptation to new host niches (19, 54). Over 100 of the ∼2,000 open reading frames (ORFs) in the pathogenic Neisseria are potentially phase variable and subject to correction by MMC (47). Many of the phase-variable genes in the pathogenic Neisseria encode or produce antigenic outer membrane surface structures, including lipooligosaccharide, opacity-associated (Opa) proteins, iron acquisition proteins, meningococcal capsule, and type IV pili (48). Pilus phase variation, the phenotypic switch between piliated and nonpiliated states, is mediated by two distinct mechanisms. Antigenic variation of the pilin protein (pilin Av) occurs by high-frequency RecA-dependent gene conversion of the pilE expression locus with sequences encoded at transcriptionally silent pilS loci (reviewed in references 12 and 19). A subset of pilE variants encode truncated or nonfunctional pilins, resulting in a nonpiliated phenotype (5, 9, 51, 52). The pilus structural protein PilC also undergoes phase variation but via RecA-independent slipped strand mispairing at a mononucleotide tract in the coding regions of the two pilC genes (16). Phase variation of pilC1/2 leads to on/off phase variation of the pilus (16, 30) and may also provide for alternative effects on transformation competence and host cell adhesion conferred by the two PilC versions in N. meningitidis (31, 33, 35, 40).

MMC plays an important role in the natural history of meningococcal infections. In a survey of serogroup A meningococcal strains, those isolated from individuals with invasive disease exhibited an increased frequency of phase variation of hmbR and hpuAB loci (37, 38). Many of these strains were found to carry inactivating mutations in mutS and mutL (38). The overrepresentation of MMC-deficient bacteria in invasive disease isolates suggests an increased mutation rate drives the generation of strains that are especially fit for causing epidemics of meningococcal meningitis. Because the Neisseria are naturally competent for transformation, mutant alleles that arise as a consequence of MMC deficiency can be rapidly exchanged among bacteria, enhancing the overall fitness of the population. The influence of MMC on other aspects of neisserial recombination and repair activities remains to be elucidated.

To systematically define the functions of MMC in N. gonorrhoeae, the mutS and mutL homologues of strain FA1090 were inactivated and the resulting mutants were compared to parental and uvrD mutant bacteria. Absence of MMC enhanced the frequency of PilC-dependent phase transitions and resistance to antibiotics. Unexpectedly, the absence of mutS, but not uvrD, enhanced the frequency of pilin Av as measured in a DNA sequencing assay. We conclude that in addition to its roles in repairing base-pairing errors and insertion-deletion loops, the gonococcal mismatch repair system limits the frequency of RecA-dependent gene conversion events at pilE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli OneShot TOP10 and DH10B competent cells (Invitrogen) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar at 37°C for plasmid propagation. Plate media contained 15 g of agar per liter.

Gc strains were maintained on Gc medium base (Difco) plus Kellogg's supplements I and II (18) (GCB) and routinely grown for 16 to 20 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Gc used in this study were translucent derivatives of strain FA1090 encoding pilin variant 1-81-S2 (46). The recA6 background contains an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-regulatable Gc recA allele and allows for control of recA expression and recA-dependent processes (44). IPTG was used at a 1 mM final concentration to provide maximal induction of recA transcription, which yields RecA expression levels and RecA-dependent phenotypes similar to that of strains with a wild-type recA gene (50).

Minitransposon construction.

A recombinant mini-Tn5 transposon conferring erythromycin resistance was created using the EZ::Tn5 transposon construction system (Epicentre). The EZ::TN pMOD-2<MCS> plasmid (Epicentre) was digested with HindIII and PstI and ligated with an identically cut fragment from plasmid pErmUP containing the ermC gene linked to a gonococcal uptake sequence (20). The ligation was transformed into DH10B E. coli, and transformants were selected on plates containing100 μg/ml ampicillin and 275 μg/ml erythromycin to yield plasmid pMODErmC. To produce the recombinant transposon, pMODErmC was linearized with AatII, and the transposon was amplified with KOD HotStart (Novagen) using FP-1 and RP-1 primers (Epicentre) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR product was digested with PshAI at 25°C for 18 h followed by DpnI digestion at 37°C to degrade the remaining plasmid template, and the transposon preparation was cleaned using a QiaQuick PCR purification column (Qiagen). The resulting transposon was designated mini-Tn5<ERM>.

Construction of MMC mutants.

A 1,730-bp internal fragment of mutS (NG1930) was amplified with KOD HotStart (Novagen) using primers MUTS-1GCU (5′-GAGCCGTCTGAAGTGGAAGCGGCGAAATTGTTGG-3′) (the gonococcal uptake sequence is underlined) and MUTS-2REV (5′-CATATAGGTGGATTTGCCGCCC-3′), with an annealing temperature of 53°C. The resulting PCR product was gel purified and ligated into pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen), and the ligation mix was transformed into TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transformants were selected on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Plasmid containing mutS was subjected to in vitro transposition using mini-Tn5<ERM> following the pMOD<MCS> protocol from Epicentre. The in vitro-transposed plasmids were transformed into TOP10 E. coli. Transposon insertion sites in erythromycin-resistant (Ermr) clones were mapped by PCR using SqRP and FP primers (Epicentre). One clone where the mini-Tn5<ERM> had inserted at the 5′ end of mutS was selected, and DNA sequencing with mutS-specific and transposon-specific primers showed that the transposon had inserted 794 bp downstream of the start codon of mutS on the noncoding strand (Fig. 1). The mutS::erm clone was transformed into FA1090 1-81-S2 and the recA6 derivative, and transformants were selected on plates containing 0.75 μg/ml erythromycin. Replacement of the parental mutS allele with mutS::erm was verified by PCR and Southern blotting of BfaI-digested chromosomal DNA with a mutS gene probe.

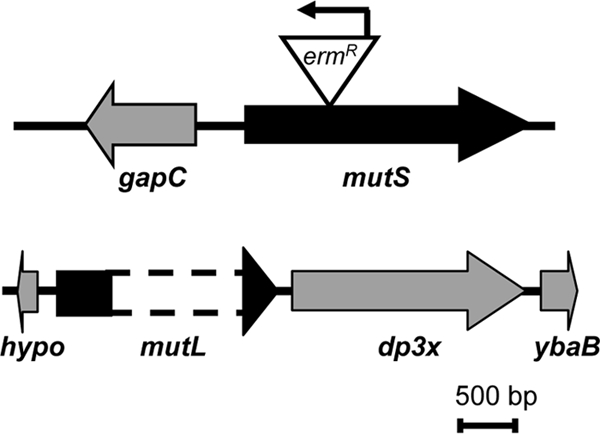

FIG. 1.

mutS and mutL genes in Gc strain FA1090. Open reading frames are indicated by open block arrows, which point in the direction of transcription. Names of open reading frames are shown underneath the arrows (hypo, hypothetical protein encoded by NG0745). Solid lines connecting block arrows are predicted intergenic regions. The triangle denotes the position of the mini-Tn5<ERM> transposon insertion in mutS, with the arrow pointing in the direction of Erm transcription. The region deleted in mutL is indicated by the dotted lines. Drawings are to scale. Bar, 500 bp.

To create an in-frame deletion of the central 1,062 bp of mutL, the 5′ fragment of mutL was amplified with primers MUTL-3 (5′-CCGCGGCAGTGAGCGTATTCGGTGTTTTCG-3′) and MUTL-4 (5′-GCTTACATTGATGTCGCAGGCGG-3′), and the 3′ fragment of mutL was amplified using primers MUTL-1 (5′-CGTAAGACGAATTGTAGGCAGC-3′) and MUTL-2 (5′-CCGCGGGCTTATTCCCGTAACCTTTGCC-3′) (SacII restriction sites in MUTL-2 and MUTL-3 are underlined). Each was ligated into pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen) and transformed into TOP10 E. coli, and the products were verified by diagnostic digestion and DNA sequencing. A SpeI/SacII fragment from pMutL3-4 was ligated into XbaI- and SacII-digested pMutL1-2 to create pMutLΔ. pMutLΔ was spot transformed into FA1090 1-81-S2 and the recA6 derivative. Clones that exhibited enhanced pilus-dependent colony morphology changes (PDCMC), potentially indicative of an MMC deficiency, were passaged on GCB. Clones retaining enhanced PDCMC on passage were screened by PCR for deletion of mutL by using the primer set MUTLSCREENFWD (5′-GGCGGTTGATGTGGAACTGG-3′) and MUTLSCREENREV (5′-CGGATTTGCCCAACATTACGG-3′). Clones with the mutL deletion were verified by Southern blotting with HpaII-digested chromosomal DNA and a mutL gene probe.

Complementation.

MMC mutants were complemented using the neisserial insertional complementation system (NICS) (27), in which a functional copy of the gene of interest is inserted into the Gc chromosome between the lctP and aspC genes, an ectopic site unlinked to the original mutations. mutS was amplified from FA1090 chromosomal DNA with KOD HotStart polymerase using primers MUTSCOMPREV (5′-ATCGATGCATATAAAGTTTATCCACAGATTTTTCC-3′) (SalI restriction site underlined) and MUTSCOMPFWD (5′-ACGTGTCGACAATTTCGCTATTTCAAAAACGCGC-3′) (NsiI restriction site underlined), with a 60°C annealing temperature. This primer set amplifies 322 bp upstream of the mutS start codon and 58 bp downstream of the stop codon. The PCR product was ligated into pCR-Blunt, the plasmid mix was transformed into OneShot TOP10 E. coli, and transformants were selected on LB with 50 μg/ml kanamycin to yield pBluntMutS. The cloned mutS was sequenced on forward and reverse strands to verify that no mutations had been introduced during PCR amplification. pBluntMutS was digested with SalI and NsiI to liberate the mutS fragment, which was ligated into SalI-NsiI-digested pGCC5 complementation vector. The ligation mix was transformed into TOP10 E. coli, and transformants were selected on LB agar containing 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol, yielding pGCC5MutS. pGCC5MutS was spot transformed into FA1090 mutS mutants, and transformants were selected on 0.75 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Incorporation of the complement construct into the NICS site was validated by Southern blotting with ClaI-digested chromosomal DNA and a mutS-specific gene probe.

To complement the mutL mutant, the region encompassing the mutL coding sequence and putative promoter was amplified using KOD HotStart and the primers MUTLCOMPFWDSAL (5′-GTCGACGGTTGAGGAATTGTGTGGC-3′) (the SalI restriction site is underlined) and MUTLCOMPREVNSI (5′-ATGCATGGCGTAGAACTTGATAGGCC-3′) (NsiI restriction site is underlined). This primer pair amplifies 187 bp upstream of the mutS start codon and 118 bp downstream of the stop codon. The product was ligated into pCRIIBlunt-TOPO (Invitrogen), transformed into TOP10 E. coli, and selected on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. From the resulting plasmid, pBluntMutL, the mutL gene was sequenced on forward and reverse strands to verify that no errors were introduced during amplification. pBluntMutL was digested with SalI and NsiI, and the mutL-containing fragment was ligated into SalI- and NsiI-digested pGCC5. Ligations were transformed into TOP10 E. coli, and transformants were selected on LB agar with 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The resulting plasmid, pGCC5MutL, was spot transformed into FA1090 mutL mutants, and transformants were selected on 0.6 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Incorporation of the complement into the NICS site was validated by Southern blotting with ClaI-digested chromosomal DNA and a mutL-specific gene probe.

Construction of MMC double mutants with uvrD or ΔpilE.

The FA1090 uvrD::kan mutant and complement have been described (23a). uvrD::kan genomic DNA was transformed into FA1090 1-81-S2 MMC mutants, and colonies were isolated that were resistant to 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The presence of the uvrD mutation and retention of the MMC mutation were confirmed by Southern blotting with gene probes specific for uvrD, mutS, and/or mutL.

To generate nonpiliated derivatives of MMC-deficient Gc, ΔpilE genomic DNA (2) was transformed into FA1090 1-81-S2 MMC mutants, and colonies were isolated with nonpiliated (P−) morphology. Deletion of pilE was confirmed by Southern blotting on ClaI-digested chromosomal DNA using a pilE-specific probe, and retention of the MMC mutation in strains lacking pilE was confirmed by Southern blotting with mutS- or mutL-specific gene probes.

Spontaneous mutation assays.

FA1090 ΔpilE derivatives of the indicated strains were collected into GCBL at a concentration of 107 to 108 CFU/ml. The starting CFU/ml values were determined after 24 h of growth of diluted Gc cultures on nonselective GCB plates. A 0.1-ml aliquot of each culture was plated on each of five GCB plates containing 50 ng/ml rifampin or 0.8 μg/ml nalidixic acid. Antibiotic-resistant CFU were enumerated after ∼40 h growth. The frequency of spontaneous antibiotic resistance was calculated by dividing the number of antibiotic-resistant CFU/ml by the total CFU/ml. Experiments were conducted 10 times for each strain, and results are presented as the median frequency of spontaneous mutation, with the 25th and 75th percentiles indicated. Statistical comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and differences were considered significant at a P level of <0.05.

UV sensitivity assays.

Piliated (P+) FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 and the isogenic mutS and uvrD mutants were serially diluted onto GCB plates either containing IPTG to activate recA expression or without IPTG to repress recA expression. Plates were exposed to 0 to 80 J/m2 of UV irradiation using a Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). CFU were quantified after 24 h of growth, and survival was calculated relative to unirradiated Gc of the same strain. Statistical differences were calculated using Student's two-tailed t test on log10-transformed data at matched UV fluences and were considered significant at a P level of <0.05.

Transformation assays.

P+ FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 and isogenic mutants in mutS and mutL were suspended in transformation medium (1.5% proteose peptone no. 3 [Difco], 0.1% NaCl, 200 mM HEPES [Sigma], 5 mM MgSO4, 1 mM IPTG, and Kellogg supplements I and II, pH 7.2) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼1.5. Thirty microliters of each cell suspension was added to tubes containing 2 ng transforming DNA (see below). After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, transformation mixtures were added to prewarmed transformation medium and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 for 4 h. Serial dilutions of each mixture were spotted on GCB plates in the presence and absence of the appropriate antibiotic selection. Transformation efficiencies are reported as antibiotic-resistant CFU divided by total CFU and are the means of six replicates. Statistical differences were calculated using Student's two-tailed t test and were considered significant at a P level of <0.05.

Transformation substrates: point mutation.

Genomic DNA was prepared from a spectinomycin-resistant (Spcr) isolate of FA1090 1-81-S2. Spectinomycin resistance in this isolate is due to a point mutation (A70C) in the rpsE gene. The rpsE locus was amplified by PCR with KOD HotStart polymerase (Novagen) using primers rpsE2top (5′-TCCAATATCACGGTCGTGTG-3′) and rpsE3botGUS (5′-CATGCCGTCTGAAGATTCAATTGTACCAATCAGGC-3′), with an annealing temperature of 55°C, cloned into pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen), and transformed into TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen).

Transformation substrates: insertion.

Plasmid pNGO554::Kan-2 and the resulting Gc strain, FA1090 1-81-S2 ngo554:kan, have been described previously (49).

PDCMC assay.

Pilin variation was measured using a modified version of the PDCMC assay, in which P− outgrowths emerging from several P+ colonies are monitored over time (42). Colony variation in 10 P+ Gc colonies grown on agar medium was scored at 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 h of growth using a stereomicroscope, with 0 denoting no P− outgrowths, 1 a single P− outgrowth, etc. Colonies with four or more P− outgrowths were given a score of 4. Results are the averages of 6 to 10 independent experiments per strain ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences were calculated using Student's two-tailed t test at matched time points and were considered significant at a P level of <0.05.

PilC expression.

P+ FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 mutS and mutL Gc were grown on GCB without IPTG. Single P− outgrowths arising from each of four P+ colonies from each strain were isolated and streak purified for the presence of homogeneous P− colonies. Lysates from the P− isolates were immunoblotted for PilC expression using anti-PilC antiserum (33) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Chemicon). FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 served as a positive control for PilC expression.

Opa phase variation assay.

Single transparent colonies of FA1090 ΔpilE and the isogenic mutS and mutL mutants and complements were collected into 1 ml GCBL. The suspensions were serially diluted and plated onto GCB agar. The frequency of Opa phase variation was determined by dividing the number of CFU exhibiting an opaque phenotype, indicative of expression of Opa proteins, by the total number of CFU present. The average frequency of Opa phase variation was calculated from 10 colonies per strain. Parental and MMC-deficient Gc were not statistically significantly different in Opa phase variation as determined by Student's two-tailed t test at a P level of <0.05.

Sequencing assay of Av.

The sequencing assay of pilin Av was performed with P+ FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 Gc and the uvrD and mutS derivatives as originally described (5). Given the frequency of P− colony emergence in uvrD- and mutS-deficient backgrounds, care was taken to selectively passage P+ colonies that had no P− outgrowths. Progeny pilE sequences were aligned with the 1-81-S2 parental pilE sequence and the 21 pilS copies in the FA1090 genome using the AlignX function of Vector NTI software (Invitrogen). The experiment was conducted twice, each time with an independently derived mutS mutant, and results are presented as the median frequency of pilin Av, with 25th and 75th percentiles indicated. Statistical differences were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and were considered significant at a P level of <0.05.

pilE sequence analysis of P− mutS Gc.

FA1090 1-81-S2 recA6 mutS Gc were passaged on GCB plates containing 1 mM IPTG to activate recA expression. Ninety-six P+ colonies were passaged individually on GCB plates lacking IPTG. Two P− progeny were isolated from each of the 96 colonies and individually streak purified to ensure maintenance of the P− phenotype. pilE genes were sequenced and analyzed as above.

RESULTS

Identification and mutagenesis of MMC genes in Gc.

One mutS and one mutL homolog were identified in the annotated genome of Gc strain FA1090 (GenBank accession number AE004969; annotation at http://stdgen.northwestern.edu). The 2,592-bp mutS gene (NG1930) is predicted to encode an 863-amino acid (aa) protein with 48.1% identity and 60.9% similarity to MutS from E. coli K-12 (MG1655; GenBank accession number NC_000913). Gc MutS possesses Walker A and B motifs at its C terminus, comprising the putative ATP binding domain, as found in MutS proteins from other organisms (23). Gc mutS does not appear to be in an operon (Fig. 1). In contrast, the Gc mutL gene (NG0744) is the first gene in a putative operon with dp3x, encoding the tau and gamma subunits of DNA polymerase III, followed by a 333-bp ORF with similarity to ybaB of E. coli (Fig. 1). The 1,974-bp Gc mutL gene is predicted to encode a 657-aa protein with 32.0% identity and 45.6% similarity to E. coli MutL. Gc MutL has several domains conserved in other MutL proteins, including the N-terminal histidine kinase-like ATPase domain, the central transducer domain, and a C-terminal dimerization domain (23). As reported for Neisseria meningitidis (1), BLAST analysis revealed no MutH endonuclease homolog in the genome of FA1090 or any other Gc strain (sequences available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/neisseria_gonorrhoeae/MultiHome.html). Therefore, Gc possess an intact MMC system that may not be methyl directed.

To inactivate Gc mutS, a mini-Tn5 transposon carrying erythromycin resistance was inserted at the 5′ end of the gene (Fig. 1). Because mutL appeared to be in an operon, a mutL in-frame deletion was constructed (Fig. 1). Each mutant was complemented with a functional copy of the gene inserted at an ectopic site in the chromosome unlinked to the original mutation. Neither of the mutants exhibited any growth defects on solid or liquid medium (data not shown).

Increased frequency of spontaneous mutation in Gc MMC mutants.

To examine whether the Gc mismatch repair mutants exhibited higher amounts of spontaneous mutation, the frequency of spontaneous nalixidic acid-resistant bacteria (Nalr) was measured in mutS and mutL mutants. Nalr arises from point mutations in DNA gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV (56). Disruption of mutS or mutL led to a 4- to 5-fold increase in the median frequency of appearance of Nalr colonies, a statistically significant increase over the parental strain (Fig. 2). Complementation of the mutants with wild-type copies of mutS or mutL restored the frequency of spontaneous mutation to wild-type levels (Fig. 2). Similar low increases in the frequency of spontaneous mutation have previously been reported for mutS and mutL mutants in N. meningitidis (7, 26, 38). Therefore, mutS and mutL are functional MMC genes in Gc and have modest effects on the correction of point mutations in this organism.

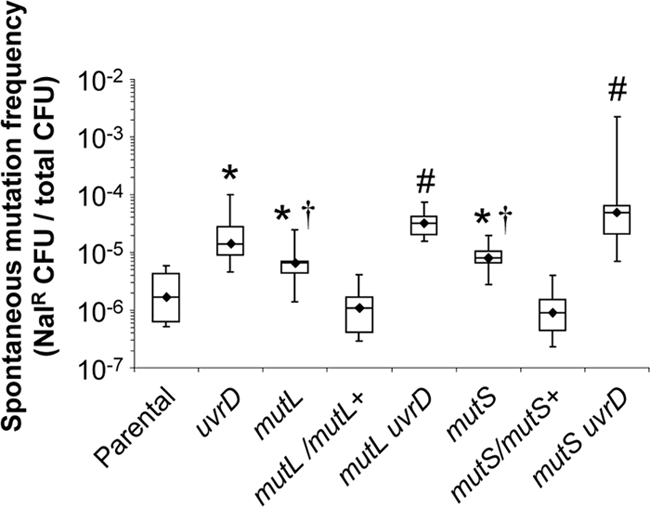

FIG. 2.

Increased frequency of spontaneous resistance to nalidixic acid in MMC-deficient Gc. FA1090 parental Gc, isogenic single or double mutants in mutS, mutL, or uvrD, and complements of mutS and mutL were plated on GCB containing nalidixic acid, and the frequency of spontaneous nalidixic acid resistance (Nalr) was calculated as the number of Nalr CFU divided by the total number of CFU plated. All strains carried a deletion of pilE to prevent pilus-mediated bacterial aggregation. Diamonds indicate the median frequencies of antibiotic resistance for 10 independent measurements per strain. Boxes below and above the median indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles of measured frequencies, respectively. Bars indicate the low and high ranges of the data points. Statistical significance was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with the following comparisons showing significance at P < 0.025: *, mutant versus parental Gc; †, mutant versus isogenic complement; #, MMC mutant versus isogenic double mutant with uvrD.

In our study on nucleotide excision repair in Gc, we reported that Gc lacking uvrD also have a higher frequency of spontaneous mutation to Nalr, which we attributed to an additional role for the UvrD helicase in MMC (23a). However, the frequency of spontaneous mutation in the Gc uvrD mutant was 2-fold higher than in the mutS and mutL mutants (Fig. 2). This effect was not specific to nalidixic acid, since the frequency of spontaneous resistance to rifampin, which is due to point mutants in rpoE, was three times higher in uvrD Gc than in mutL or mutS mutants (data not shown). Inactivating uvrD alongside mutL or mutS significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous mutation to Nalr compared to any of the single mutants (Fig. 2). These results strongly suggest that MMC and UvrD have separable effects on preventing spontaneous mutations in Gc.

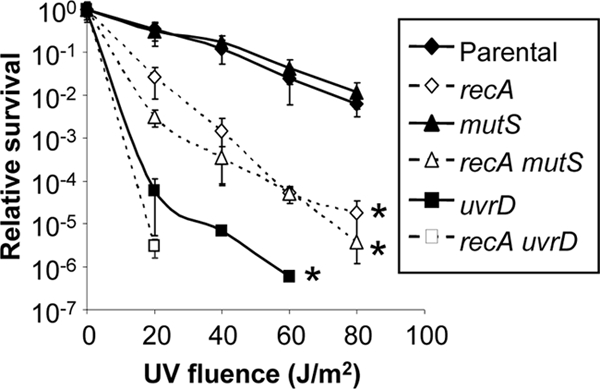

Gc MutS and MutL do not participate in survival to UV irradiation.

In E. coli, repair of DNA damaged by UV irradiation occurs primarily through recombinational repair and nucleotide excision repair, with minor contributions from MMC (29, 41, 55). To examine the involvement of MMC in repairing UV-induced DNA lesions in Gc, survival of mutS mutants was assessed after exposure to UV light. The Gc mutS mutant did not exhibit any increased sensitivity to UV irradiation than the parental strain (Fig. 3). In contrast, uvrD mutant Gc were exquisitely sensitive to UV irradiation (Fig. 3) (23a). Gc lacking recA, which is required for recombinational DNA repair, were ∼2 orders of magnitude more sensitive to UV irradiation than recA+ bacteria, but loss of mutS in the recA-deficient background had no additional effect on Gc sensitivity to irradiation, whereas survival of uvrD recA Gc was more compromised after UV exposure than either single mutant (Fig. 3) (23a). We conclude that MMC does not correct the bulky DNA lesions induced by UV irradiation and that the sensitivity of uvrD to UV damage is due to its role in Gc nucleotide excision repair.

FIG. 3.

MMC does not protect Gc from UV-induced damage. Serial dilutions of FA1090 recA6 Gc (parental) and isogenic mutants in mutS and uvrD were plated on GCB containing IPTG to activate recA expression or on GCB lacking IPTG to repress recA expression (recA). Gc were exposed to UV light at the indicated intensities. Survival was calculated relative to that of unirradiated Gc. No CFU were recovered for uvrD Gc at 80 J/m2 UV and for uvrD recA Gc at UV of >20 J/m2. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed t test on log10-transformed data, and asterisks indicate P < 0.05 for the indicated mutant relative to parental at matched UV fluences (except for recA at 20 J/m2). There was no statistically significant difference in survival between mutS and parental Gc or between mutS recA and recA Gc.

MMC does not affect Gc transformation frequencies.

Reports from a variety of organisms indicate that MMC differentially affects transformation, depending on the DNA substrate: single base pair mismatches in the recombining DNA are repaired by MMC, while larger insertions or deletions are not (4, 15, 34). To test the role of the Gc MMC system in recombination of transforming DNA in this naturally competent organism, transformation efficiencies were measured in parental, mutS, and mutL bacteria. Transforming DNA contained either a single base change in rpsE (A70C), which confers resistance to spectinomycin, or a 1.1-kb kan-2 cassette, which encodes kanamycin resistance. Incorporation of the point mutation occurs at the native rpsE gene, while the kan-2 cassette is flanked by sequences identical to the ngo554 open reading frame, a locus which is not known to have any effects on DNA uptake or transformation (A.K. Criss, E. A. Stohl, and H. S. Seifert, unpublished results). Gc were transformed with these markers either as chromosomal DNA from Gc or as cloned fragments in plasmids that are unable to replicate in Gc. For the rpsE(A70C) substrate, concentrations of DNA were chosen to produce transformation frequencies that were 100- to 1,000-fold higher than the reported spontaneous mutation frequency for specinomycin resistance in Gc (45) but were not saturating for transformation (P. D. Duffin and H. S. Seifert, unpublished results).

The transformation efficiency of the Spcr point mutation was 2- to 3-fold higher in the MMC mutants when either chromosomal or cloned plasmid DNA was used as the transformation substrate. However, these increases were only statistically significant in mutL Gc transformed with chromosomally encoded rpsE(A70C) (Table 1). No difference in transformation efficiency was observed for kan-2, whether presented as chromosomal or plasmid DNA (Table 2). We conclude that the Gc MMC machinery plays a marginal role in correcting single nucleotide mismatches incorporated via transformation in this naturally competent organism and has no effect on insertion of large sequences into the chromosome.

TABLE 1.

Transformation frequencies to spectinomycin resistance (Spcr) in parental and MMC-deficient Gc

| DNA form | Strain | Transformation frequencya | Fold increaseb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal | FA1090 | 3.83 (±1.62) × 10−6 | |

| DNA | mutL | 11.8 (±3.09) × 10−6 | 3.1c |

| mutS | 10.3 (±5.12) × 10−6 | 2.7 | |

| Cloned plasmid | FA1090 | 3.85 (±0.98) × 10−6 | |

| DNA | mutL | 10.6 (±4.03) × 10−6 | 2.7 |

| mutS | 4.43 (±2.11) × 10−6 | 1.2 |

Number of Spcr CFU/total number of CFU (± SEM).

The increase compared to the FA1090 parent.

The increase in transformation frequency relative to the FA1090 parent was statistically significant (P < 0.05, by Student's two-tailed t test).

TABLE 2.

Transformation frequencies to kanamycin resistance in parental and MMC-deficient Gc

| DNA form | Strain | Transformation frequencya | Fold increaseb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal | FA1090 | 9.24 (±3.46) × 10−5 | |

| DNA | mutL | 11.8 (±3.09) × 10−5 | 1.3 |

| mutS | 8.30 (±1.62) × 10−5 | 0.9 | |

| Cloned plasmid | FA1090 | 19.3 (±9.03) × 10−5 | |

| DNA | mutL | 29.6 (±7.44) × 10−5 | 1.5 |

| mutS | 19.2 (±7.56) × 10−5 | 1.0 |

Number of Kanr CFU/total number of CFU (± SEM).

The increase compared to the FA1090 parent. None of the increases in transformation to kanamycin resistance was statistically significant relative to the FA1090 parent.

Increased PilC phase variation but not Opa phase variation in MMC-deficient Gc.

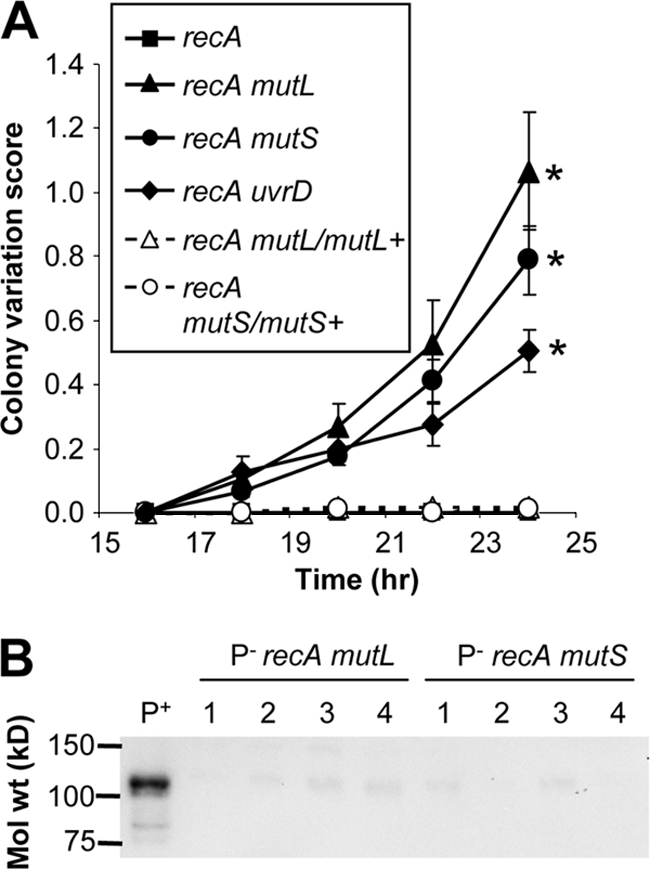

P+ FA1090 1-81-S2 Gc transformed with the mutS and mutL mutant constructs yielded colonies with a P− phenotype more frequently than in untransformed bacteria, suggesting that Gc MMC mutants undergo increased pilus phase variation. Pilus-dependent colony morphology changes were quantified using a kinetic assay for the appearance of P− outgrowths from colonies that were initially uniformly P+ (42). The colony variation index was significantly increased in the mutS and mutL mutants over that of the parental Gc (Fig. 4A). Complementation of the mutants restored pilus phase variation to parental levels (Fig. 4A). Thus, inactivation of the Gc MMC machinery enhances pilus phase variation events.

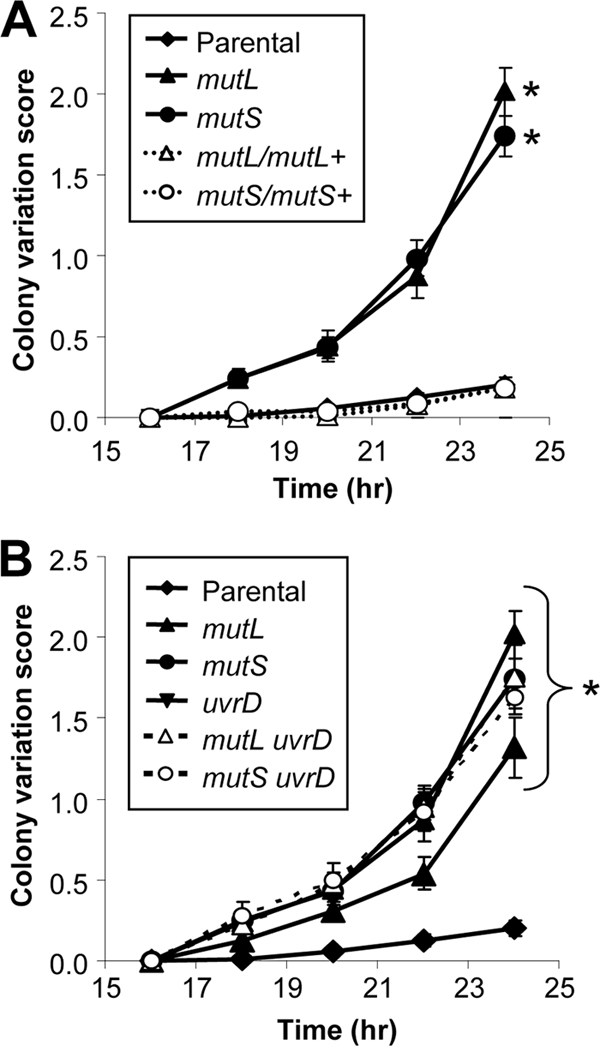

FIG. 4.

Increased frequency of pilus-dependent colony variations in MMC-deficient Gc. (A) Increased colony variation in MMC mutant Gc. FA1090 recA6 (parental) and isogenic mismatch repair-deficient and complemented strains were grown on GCB containing IPTG to induce recA expression. At the indicated times, 10 P+ colonies of each strain were examined for the emergence of P− outgrowths and scored as follows: 1, one P− outgrowth; 2, two P− outgrowths, etc. Colonies with four or more P− outgrowths were given a score of 4. The colony variation score was averaged for the 10 colonies. Results presented are the averages of 6 to 10 independent experiments per strain ± the SEM. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed t test for the indicated mutant relative to the parent at matched time points at >16 h, and asterisks indicate P < 0.01. Parental Gc grown on plates lacking IPTG to prevent recA expression did not undergo any colony morphology changes in the time course of this assay. (B) Effects of uvrD inactivation on colony variations in MMC-deficient Gc. FA1090 recA6 and single and double mutants for mutS, mutL, and uvrD were subjected to the colony variation assay as described for panel A. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed t test. All mutants exhibited significantly increased colony variation relative to the parent at matched time points (>16 h); asterisks indicate P < 0.01. There were no significant differences in colony variation for any of the single or double mutants relative to one another.

Work from our laboratory has shown that loss of uvrD also enhances the frequency of PDCMC in Gc, which we attributed to a role for uvrD in MMC (23a). FA1090 1-81-S2 uvrD Gc produced a PDCMC index that was statistically indistinguishable from that of the MMC mutants but significantly higher than that of the parent (Fig. 4B). When both MMC and uvrD were inactivated in Gc, the PDCMC index was no different from the single mutants (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that uvrD functions with MMC to correct pilus phase variation events.

Pilus phase variation can be caused by loss of PilC expression and pilin Av, but only pilin Av requires RecA, while PilC phase variation is due to RecA-independent slipped strand mispairing (16, 22). In the absence of recA expression, the mutL and mutS mutants maintained significantly higher PDCMC than parental Gc, which did not undergo any pilus phase variation in this assay (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the P− outgrowths from recA mutL and recA mutS mutants did not express PilC protein, based on immunoblotting results (Fig. 5B). Similar observations were made with uvrD-deficient Gc (23a). These findings show that some of the pilus phase variation events in MMC-deficient Gc are due to increased PilC phase variation.

FIG. 5.

Increased frequency of PilC phase variation in MMC-deficient Gc. (A) Increased colony variation in Gc lacking recA and MMC. FA1090 recA6 Gc and isogenic mutS and mutL mutants and complements were assayed for pilus-dependent colony variations as described for Fig. 4, except bacteria were grown on GCB lacking IPTG to repress recA expression. Statistical significance was calculated as for Fig. 4. The MMC and uvrD mutants exhibited a significantly higher PDCMC score than either the parental strain or its isogenic complement; asterisks indicate P < 0.025 at matched time points (>16 h). (B) Absence of PilC in P− outgrowths isolated from Gc lacking recA and MMC. P+ FA1090 recA6 Gc lacking mutL or mutS were grown on GCB without IPTG to repress recA expression. Lysates from four P− colonies for each strain were isolated (labeled 1 to 4). Lysates from the P− bacteria and FA1090 recA6 (P+) were immunoblotted for expression of the 110-kDa PilC protein.

While the PilC phase varies with the length of a monoguanosine repeat tract in the PilC signal sequence, phase variation of the outer membrane Opa proteins is due to changes in the number of CTCTT repeats in the 5′ end of the opa genes (32). The frequency of Opa phase variation was measured as the percentage of phenotypically Opa+ bacteria arising in an Opa− background. No significant difference in Opa phase variation frequency was measured between parental and MMC-deficient Gc (data not shown). We conclude that MMC limits slipped strand mispairing within monomeric repeat tracts in Gc but does not affect the variation within pentameric repeats.

Increased frequency of pilin Av in Gc MMC mutants.

The colony variation score for MMC-deficient Gc was higher for bacteria expressing RecA than those without RecA (compare axes in Fig. 4 and 5A), indicating that PilC phase variation could not account for all the pilus phase variations occurring in Gc. To test whether MMC-deficient Gc also underwent an increase in pilin Av, changes at pilE were measured using a DNA sequencing assay (5). This assay is independent of pilus phase transitions, since it detects sequence changes in P+ progeny arising from a P+ parent carrying a defined pilE. The frequency of pilin Av was enhanced 3-fold in mutS Gc compared to the isogenic parent, a statistically significant difference (Table 3). In contrast, inactivation of uvrD did not change the frequency of pilin Av (Table 3) (23a). Therefore, inactivation of MMC in Gc also enhances the frequency of recombination at pilE, and this occurs independently of UvrD helicase.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of pilin Av in mutS- and uvrD-deficient Gc

| Strain | Expt 1 |

Expt 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Variant pilEa | Frequency of pilin Avb | % Variant pilEa | Frequency of pilin Avb | |

| Parent | 12.5 (8.3, 12.5) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.13) | 8.3 (6.4, 14.6) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.15) |

| mutS | 27.1 (20.8, 31.1)c | 0.27 (0.22, 0.31)c | 26.1 (25.5, 38.3)c | 0.28 (0.26, 0.40)c |

| uvrD | 8.5 (4.3, 12.5) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.13) | NDd | ND |

Median percentage of variant (nonparental) pilE sequences; the 25th and 75th percentiles are shown in parentheses.

Median frequency of pilin Av, defined as the number of recombination events per pilE; the 25th and 75th percentiles are shown in parentheses.

The increase was statistically significant relative to the FA1090 parent (P < 0.005, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

ND, not determined.

In the mutS mutant, pilE sequence changes could have arisen either from uncorrected replication errors or from pilE/pilS recombination. Only 1 of the 153 pilE variants arising in two independent experiments with mutS Gc had a sequence change attributable to the absence of mismatch correction: a single A→T change at nucleotide 187 of 1-81-S2 (no pilS copy in FA1090 has a T at this position). The other 152 pilE recombination events appeared to arise from pilE/pilS recombination, because the same sequence changes were present in at least one pilS copy and also occurred in MMC-proficient Gc. The increase in pilin Av in mutS Gc was due to a higher percentage of progeny with nonparental pilE sequences as well as an increased number of recombination events per pilE sequence (Table 4). These recombination events appeared to be an expansion of the events detected in parental Gc and involved the same subset of pilS copies (5).

TABLE 4.

Recombination events at pilE in parental and mutS Gc

| Strain | Expt no. | No. of recombination events | No. of bp different from 1-81-S2a | Length of recombinant tractb | Shared pilE/pilS sequence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′c | 3′d | |||||

| Parental | 1 | 25 | 7 | 48 | 41 | 45 |

| 2 | 27 | 7 | 15 | 55 | 40 | |

| Avg of 1 and 2 | 26 | 7 | 31.5 | 48 | 42.5 | |

| mutS | 1 | 71 | 7 | 39 | 55 | 45 |

| 2 | 81 | 9 | 50 | 27 | 45 | |

| Avg of 1 and 2 | 76e | 8 | 44.5 | 41 | 45 | |

Median number of base pairs in the recombination tract that differed from the 1-81-S2 parental pilE sequence.

Median minimum length of contiguous pilS sequence incorporated into 1-81-S2 pilE.

Median amount of contiguous sequence identity between pilE and pilS 5′ to the pilE recombination tract.

Median amount of contiguous sequence identity between pilE and pilS 3′ to the pilE recombination tract.

The difference between parental and mutS Gc is statistically significant for the number of recombination events at pilE (P = 0.01, Student's t test) but not for any of the other parameters reported in the table.

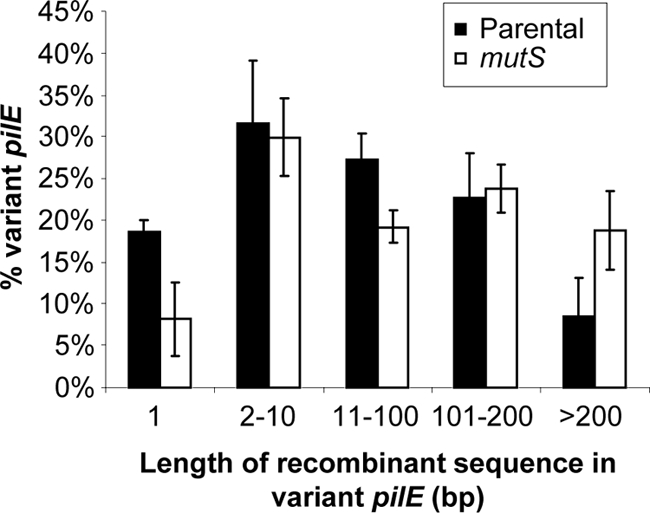

We examined the length and position of the recombination tracts in variant pilE sequences in parental and mutS-deficient Gc. Since the points of recombination between pilE and pilS cannnot be absolutely identified, the length of the recombination tracts was defined as the minimum stretch of contiguous pilS sequence that would produce the variant when introduced into pilE. Inactivation of mutS did not affect the overall position of recombinant sequence in pilE (e.g., semivariable versus hypervariable regions) (data not shown). However, the length of the recombination tracts in mutS-deficient pilin variants was 1.5-fold longer that of the parent strain (Table 4). In addition, pilE variants in the mutS background underwent fewer single base pair changes and more recombination events of >200 bp in length (Fig. 6). However, the number of base pairs of shared pilE/pilS sequence flanking the recombination tracts was similar between the parental and mutS pilin variants (Table 4). Thus, in the absence of MMC, Gc produces more pilin antigenic variants, and the variants exhibit longer stretches of recombinant sequence at pilE.

FIG. 6.

Increased length of the recombinant sequence at pilE in mutS Gc. The minimum length of pilS sequence donated to pilE was measured in P+ antigenic variants arising from parental and mutS-deficient FA1090 Gc. Results are expressed as the percentage of the total number of variant pilE sequences examined in two independent experiments. The differences between parental and mutS Gc did not achieve statistical significance.

To examine the contribution of pilin Av to the appearance of P− colonies in MMC-deficient Gc, the mutS mutant was subjected to a modified sequencing assay, where P− progeny arising from the 1-81-S2 precursor were examined for changes at pilE. Sixty-seven percent of the P− mutS isolates retained 1-81-S2 pilE sequence (58%) or carried a pilE sequence known to otherwise produce P+ morphology (9%) and were therefore characterized as PilC phase variants. In contrast, PilC phase variation only accounted for 15% of P− progeny from parental 1-81-S2 Gc (5). Correspondingly, 28% of mutS progeny carried variant pilE sequences that could give rise to P− phenotypes, compared with 59% of parental bacteria which coded for both full-length and truncated pilins (5). Four percent of mutS progeny had a deletion of the pilE locus where the gene could not be amplified with pilE-specific primers.

Taken together, these results show that MMC-deficient Gc undergo a substantial increase in pilus phase transitions due to increases in the frequencies of both PilC phase variation and pilin Av. From these results we draw two main conclusions. First, MMC in Gc prevents changes to mononucleotide stretches of DNA, which may involve the UvrD helicase. Second, MMC also limits recombination events at pilE in pilin Av, both in number and length of recombinant sequence, and this process is independent of UvrD.

DISCUSSION

In this study we took a genetic approach to examine the roles of MMC in the human-specific pathogenic Gc, and we have drawn several conclusions. First, Gc encode a functional MMC system comprised of MutL and MutS gene products. Second, Gc MMC repairs mismatches and single nucleotide insertions/deletions to limit spontaneous mutations and slipped-strand mispairing, respectively. Third, Gc MMC has a minor but detectable role in preventing single base pair mismatches introduced via natural transformation and homologous recombination. Fourth, Gc MMC has the previously unrecognized capability of correcting pilE/pilS recombination events underlying pilin Av. We postulate that in Gc, the effectiveness of the MMC system dictates the frequency of variation of a variety of surface-exposed structures, which are likely to aid bacterial evasion of human humoral immune surveillance.

This work reveals that there are notable differences between Gc MMC and the E. coli paradigm. In E. coli, MMC mutants exhibit a striking increase in the frequency of spontaneous mutation to antibiotic resistance (reviewed in reference 3), whereas the increase in mutation frequency to Nalr in MMC-deficient Gc was only 4- to 5-fold above the parental strain. This observation is in agreement with the effects of MMC inactivation in N. meningitidis (7, 26, 38). While in E. coli uvrD (also termed mutU) and mutS/L mutants have similar effects on spontaneous mutation (28), in Gc the mutation frequency in uvrD MMC double mutants is significantly higher than any single mutant. Therefore, UvrD appears to have an additional role beyond MMC in this organism in repairing DNA lesions that create point mutations. Intriguingly, that role is unlikely to be through uvrD's other ascribed function in nucleotide excision repair, as uvrABC mutants do not exhibit an increase in spontaneous mutations (23a).

Another striking difference between the Gc and E. coli pathways for MMC is the absence of a MutH endonuclease homologue in Gc, which in E. coli discriminates the newly synthesized, mutated, unmethylated strand of DNA from the methylated parent. Gc are among many organisms, including humans, that lack MutH homologues, and MutL itself may compensate for the absence of MutH in these organisms through its latent endonucleolytic activity (1). Notably, Gc MutL contains the D[M/Q]HA(X)2E(X)4E motif that defines the nuclease domain in human MutLα (17), and Gc MutL was shown to possess nicking endonuclease activity on DNA in vitro in a divalent cation-dependent manner (8). From these analyses, we infer that recognition and repair of mismatches in Gc differs substantially from E. coli, and the genetic tractability of Gc makes this organism an attractive model for exploring the mechanism underlying methyl-independent MMC.

At least 5% of the open reading frames of the pathogenic Neisseria are proposed to be subject to phase variation due to the presence of repeat tracts that would be subject to slipped strand mispairing during replication (47). Gc MMC mutants exhibited higher rates of phase variation at a monoguanosine repeat tract in PilC, leading to pilus-dependent colony morphology changes. These results are in agreement with the increased frequency of phase variation at monomeric nucleotide tracts in the hmbR and hpuAB genes in N. meningitidis MMC mutants (37). Although we expected the Gc uvrD mutant to exhibit the same frequency of pilus phase variation as the mutS/L mutants, PilC-dependent phase variation was marginally higher in the absence of mutS or mutL compared to uvrD; however, Gc lacking MMC along with uvrD did not show enhanced pilus phase variation relative to single mutants. We attribute this slight increase in pilus phase variation to the additional role of MMC in pilin Av, with some of the antigenic variants conferring a P− phenotype on the bacterial colonies (see below).

Gc are naturally competent for DNA uptake and use transformation as their primary route for genetic exchange (19). Transformation requires components of the neisserial type IV pilus apparatus, including the PilQ secretin, PilT retraction ATPase, the major pilin encoded by pilE, and minor pilins, as well as a specific 12-bp sequence on the incoming DNA (reviewed in reference 10). Incorporation of exogenous DNA into the genome requires RecA-dependent homologous recombination (22). Our results show that MMC has a minor effect on correcting transformation-induced changes to the FA1090 genome. The modest effect of MMC on transformation with the the rpsE(A70C) construct conferring spectinomycin resistance may reflect that Gc are extremely efficient at recombining DNA into the genome, leaving little opportunity for MMC-based correction. Alternatively, Gc MMC may not effectively recognize mismatched DNA in the context of the strand invasion intermediate postulated for RecA-dependent recombination, as suggested for E. coli MMC (57).

Like natural transformation, the Neisseria-specific process of pilin Av requires RecA-dependent strand invasion for incorporation of unexpressed pilS sequence into the pilE locus and resolution of Holliday junction-type intermediates through RuvABC and RecG activities (12, 19). However, unlike transformation, pilin Av is considered a form of gene conversion, as only the pilE locus is changed while the donor pilS copy remains unchanged (9, 43, 52). Also, in contrast to transformation with discrete substrates harboring single mismatches to DNA, pilS copies contain multiple mismatches relative to pilE that are flanked by short (≥2-bp) stretches of conserved sequence (5, 14). Because of the limited sequence identity among pilS copies with pilE, similarities have been drawn between pilin Av and homeologous recombination, a process which is limited by MMC (15, 36, 58). Here we have shown that gonococcal MMC similarly limits the frequency of pilin Av. Because of the cost of large-scale sequencing for the pilin Av sequencing assay, we did not measure pilin Av in the mutL mutant, but we expect it to be similarly enhanced, given the identical phenotypes of mutL and mutS mutants throughout this work. Although it was recently reported that inactivation of mutS in Gc strain MS11 did not affect pilin Av (12), we believe this discrepancy to be due to the different methodologies employed for measuring pilin Av rather than differences between Gc strains. We make this argument based on our observations that inactivation of MMC did not skew the complement of pilS copies appearing in the variant pilE genes, nor did it affect the location of the pilS sequence within pilE (i.e., semivariable or hypervariable regions). The MS11 study used reverse transcription-PCR to detect incorporation of a subset of pilS sequences into one variable region of pilE, while the DNA sequencing assay we employed has the ability to identify any variant sequence changes at any position in pilE (discussed in reference 11).

Use of the sequencing assay revealed that the pilE variants emerging in the mutS background were an expansion of those previously described for this parental strain (5), ranging from single base pair changes to replacement of the entire variable region of pilE with a corresponding pilS copy, and did not appear to be due to mutation processes. Inactivation of mutS decreased the appearance of antigenic variants with single base pair changes and increased the appearance of variants with >200 bp of incorporated pilS sequence. Thus, MMC limits the number of antigenic variants recovered from Gc and constrains the length of the pilE/pilS recombination tract. The P− pilE variants arising in the mutS background were also an expansion of those seen in the parental background. Although some pilS copies possess monocytosine repeat tracts that have been shown to be subject to slipped strand mispairing and production of P− antigenic variants (22), none of the P− variants we examined had undergone this event (data not shown). The absence of these sequences may be attributed to the small number of P− antigenic variants relative to PilC phase variants we recovered and the infrequency of detecting the recombination of pilS copies carrying the monocytosine repeat tracts into the 1-81-S2 starting pilE (5, 39).

The enhanced pilin Av in MMC-deficient Gc differs substantially from the situation in uvrD mutant Gc, where the frequency of pilin Av is no different from that of the parent. These results suggest that a helicase other than UvrD functions with MMC during pilin Av, or that helicase activity is not required at the step(s) of pilin Av where MMC activity is required. Several gene products annotated as helicases in the Gc genome have been examined for their effect on pilin Av, but none of the corresponding mutants exhibits the increase in pilin Av seen in the mutS mutant. In fact, Rep, RecQ, RuvAB, and RecG helicases all show decreased pilin Av when insertionally inactivated (21, 27, 42). Determining which, if any, helicase functions with MMC in pilin Av will require a more thorough understanding of the DNA dynamics underlying recombination at pilE. Models postulated for pilin Av include the generation of a circular pilE-pilS hybrid intermediate (13) and a single-stranded pilE-pilS fusion product that invades pilE by a successive half-crossing-over mechanism (27). Together, these results suggest the interplay between MMC and recombinational repair during pilin Av, but whether these processes function simultaneously or at discrete steps awaits further analysis.

Although enhanced mutation frequencies are generally considered detrimental to an individual organism, mutator strains provide a given population with a wellspring of genetic diversity that enhances the overall fitness of the species. This is especially true for the pathogenic Neisseria strains, where mutators are frequently isolated from epidemic-associated, invasive strains of N. meningitidis compared to related strains that colonize the nasopharynx and rarely cause invasive disease (38). Disrupted genes in N. meningitidis that produce a mutator phenotype include mutS and mutL as well as the fpg and mutY glycosylases of base excision repair and 8-oxo-guanine repair pathways (6, 37, 38, 53). The role of mutators in the natural history of Gc is less well understood, but we presume that mutator clinical isolates of Gc do exist and will be found to lack active MutS or MutL. Generation of genetic diversity through mutators would contribute to the pathogenic potential of Gc, since having a more diverse repertoire of genes available to the population would facilitate bacterial adaptation to and survival within a single host. Additionally, the natural history of sexually transmitted infections invokes the presence of a core group of individuals that reinfect one another at high rates (24). The combination of increased genetic diversity in Gc with enhanced phase variation of bacterial surface structures would allow Gc to continually reinfect this core group, in spite of induction of host humoral immunity. We postulate that the generation of genetic diversity by mutators lacking the MMC system or by a transient downregulation of MMC activity, in combination with natural competence for uptake of mutator-produced allelic variants, confers on the pathogenic Neisseria strains a remarkable and robust system for exchanging genetic traits that have the overall outcome of enhancing bacterial survival and persistence within the human population.

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present members of the Seifert laboratory for helpful discussions on this project.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI044239, R01 055977, and R37 AI033493 to H.S.S. A.K.C. was partially supported by NIH grants F32 AI056681 and K99 TW008042.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambur, O. H., T. Davidsen, S. A. Frye, S. V. Balasingham, K. Lagesen, T. Rognes, and T. Tonjum. 2009. Genome dynamics in major bacterial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:453-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, C. J., D. M. Tobiason, C. E. Thomas, W. M. Shafer, H. S. Seifert, and P. F. Sparling. 2004. A mutant form of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilus secretin protein PilQ allows increased entry of heme and antimicrobial compounds. J. Bacteriol. 186:730-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra, I., A. J. O'Neill, and K. Miller. 2003. The role of mutators in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Drug Resist. Updat. 6:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claverys, J. P., V. Mejean, A. M. Gasc, and A. M. Sicard. 1983. Mismatch repair in Streptococcus pneumoniae: relationship between base mismatches and transformation efficiencies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:5956-5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Criss, A. K., K. A. Kline, and H. S. Seifert. 2005. The frequency and rate of pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 58:510-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidsen, T., M. Bjoras, E. C. Seeberg, and T. Tonjum. 2005. Antimutator role of DNA glycosylase MutY in pathogenic Neisseria species. J. Bacteriol. 187:2801-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidsen, T., H. K. Tuven, M. Bjoras, E. A. Rodland, and T. Tonjum. 2007. Genetic interactions of DNA repair pathways in the pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 189:5728-5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duppatla, V., C. Bodda, C. Urbanke, P. Friedhoff, and D. N. Rao. 2009. The C-terminal domain is sufficient for endonuclease activity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MutL. Biochem. J. 423:265-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagblom, P., E. Segal, E. Billyard, and M. So. 1985. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature 315:156-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton, H. L., and J. P. Dillard. 2006. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 59:376-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helm, R. A., and H. S. Seifert. 2009. Pilin antigenic variation occurs independently of the RecBCD pathway in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 191:5613-5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill, S. A., and J. K. Davies. 2009. Pilin gene variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: reassessing the old paradigms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:521-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell-Adams, B., and H. S. Seifert. 2000. Molecular models accounting for the gene conversion reactions mediating gonococcal pilin antigenic variation. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1146-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell-Adams, B., L. A. Wainwright, and H. S. Seifert. 1996. The size and position of heterologous insertions in a silent locus differentially affect pilin recombination in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 22:509-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humbert, O., M. Prudhomme, R. Hakenbeck, C. G. Dowson, and J. P. Claverys. 1995. Homeologous recombination and mismatch repair during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: saturation of the Hex mismatch repair system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:9052-9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson, A. B., G. Nyberg, and S. Normark. 1991. Phase variation of gonococcal pili by frameshift mutation in pilC, a novel gene for pilus assembly. EMBO J. 10:477-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadyrov, F. A., L. Dzantiev, N. Constantin, and P. Modrich. 2006. Endonucleolytic function of MutLα in human mismatch repair. Cell 126:297-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellogg, D. S., Jr., W. L. Peacock, Jr., W. E. Deacon, L. Brown, and D. I. Pirkle. 1963. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J. Bacteriol. 85:1274-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kline, K. A., E. V. Sechman, E. P. Skaar, and H. S. Seifert. 2003. Recombination, repair and replication in the pathogenic Neisseriae: the 3 R's of molecular genetics of two human-specific bacterial pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 50:3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kline, K. A., and H. S. Seifert. 2005. Mutation of the priA gene of Neisseria gonorrhoeae affects DNA transformation and DNA repair. J. Bacteriol. 187:5347-5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kline, K. A., and H. S. Seifert. 2005. Role of the Rep helicase gene in homologous recombination in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 187:2903-2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koomey, M., E. C. Gotschlich, K. Robbins, S. Bergstrom, and J. Swanson. 1987. Effects of recA mutations on pilus antigenic variation and phase transitions in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Genetics 117:391-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunkel, T. A., and D. A. Erie. 2005. DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:681-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.LeCuyer, B., A. K. Criss, and H. S. Seifert. Genetic characterization of the nucleotide excision repair system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Liljeros, F., C. R. Edling, and L. A. Nunes Amaral. 2003. Sexual networks: implications for the transmission of sexually transmitted infections. Microbes Infect. 5:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovett, S. T. 2004. Encoded errors: mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1243-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, P., L. Sun, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2004. Involvement of genes of genome maintenance in the regulation of phase variation frequencies in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiology 150:3001-3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehr, I. J., and H. S. Seifert. 1998. Differential roles of homologous recombination pathways in Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin antigenic variation, DNA transformation and DNA repair. Mol. Microbiol. 30:697-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, K., A. J. O'Neill, and I. Chopra. 2002. Response of Escherichia coli hypermutators to selection pressure with antimicrobial agents from different classes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:925-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, R. V., and T. A. Kokjohn. 1990. General microbiology of recA: environmental and evolutionary significance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44:365-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morand, P. C., E. Bille, S. Morelle, E. Eugene, J. L. Beretti, M. Wolfgang, T. F. Meyer, M. Koomey, and X. Nassif. 2004. Type IV pilus retraction in pathogenic Neisseria is regulated by the PilC proteins. EMBO J. 23:2009-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morand, P. C., M. Drab, K. Rajalingam, X. Nassif, and T. F. Meyer. 2009. Neisseria meningitidis differentially controls host cell motility through PilC1 and PilC2 components of type IV Pili. PLoS One 4:e6834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy, G. L., T. D. Connell, D. S. Barritt, M. Koomey, and J. G. Cannon. 1989. Phase variation of gonococcal protein II: regulation of gene expression by slipped-strand mispairing of a repetitive DNA sequence. Cell 56:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nassif, X., J. L. Beretti, J. Lowy, P. Stenberg, P. O'Gaora, J. Pfeifer, S. Normark, and M. So. 1994. Roles of pilin and PilC in adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:3769-3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker, B. O., and M. G. Marinus. 1992. Repair of DNA heteroduplexes containing small heterologous sequences in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:1730-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman, M., H. Kallstrom, S. Normark, and A. B. Jonsson. 1997. PilC of pathogenic Neisseria is associated with the bacterial cell surface. Mol. Microbiol. 25:11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rayssiguier, C., D. S. Thaler, and M. Radman. 1989. The barrier to recombination between Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is disrupted in mismatch-repair mutants. Nature 342:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson, A. R., and I. Stojiljkovic. 2001. Mismatch repair and the regulation of phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:645-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson, A. R., Z. Yu, T. Popovic, and I. Stojiljkovic. 2002. Mutator clones of Neisseria meningitidis in epidemic serogroup A disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6103-6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohrer, M. S., M. P. Lazio, and H. S. Seifert. 2005. A real-time semi-quantitative RT-PCR assay demonstrates that the pilE sequence dictates the frequency and characteristics of pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:3363-3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudel, T., H. J. Boxberger, and T. F. Meyer. 1995. Pilus biogenesis and epithelial cell adherence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilC double knock-out mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 17:1057-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schofield, M. J., and P. Hsieh. 2003. DNA mismatch repair: molecular mechanisms and biological function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:579-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sechman, E. V., M. S. Rohrer, and H. S. Seifert. 2005. A genetic screen identifies genes and sites involved in pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 57:468-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal, E., P. Hagblom, H. S. Seifert, and M. So. 1986. Antigenic variation of gonococcal pilus involves assembly of separated silent gene segments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:2177-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seifert, H. S. 1997. Insertionally inactivated and inducible recA alleles for use in Neisseria. Gene 188:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seifert, H. S., R. S. Ajioka, D. Paruchuri, F. Heffron, and M. So. 1990. Shuttle mutagenesis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: pilin null mutations lower DNA transformation competence. J. Bacteriol. 172:40-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seifert, H. S., C. J. Wright, A. E. Jerse, M. S. Cohen, and J. G. Cannon. 1994. Multiple gonococcal pilin antigenic variants are produced during experimental human infections. J. Clin. Invest. 93:2744-2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snyder, L. A., S. A. Butcher, and N. J. Saunders. 2001. Comparative whole-genome analyses reveal over 100 putative phase-variable genes in the pathogenic Neisseria spp. Microbiology 147:2321-2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snyder, L. A., J. K. Davies, C. S. Ryan, and N. J. Saunders. 2005. Comparative overview of the genomic and genetic differences between the pathogenic Neisseria strains and species. Plasmid 54:191-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stohl, E. A., A. K. Criss, and H. S. Seifert. 2005. The transcriptome response of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to hydrogen peroxide reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in oxidative damage protection. Mol. Microbiol. 58:520-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stohl, E. A., and H. S. Seifert. 2006. Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA recombination and repair enzymes protect against oxidative damage caused by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 188:7645-7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swanson, J., S. Bergstrom, O. Barrera, K. Robbins, and D. Corwin. 1985. Pilus- gonococcal variants. Evidence for multiple forms of piliation control. J. Exp. Med. 162:729-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swanson, J., S. Bergstrom, K. Robbins, O. Barrera, D. Corwin, and J. M. Koomey. 1986. Gene conversion involving the pilin structural gene correlates with pilus+ in equilibrium with pilus− changes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Cell 47:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tibballs, K. L., O. H. Ambur, K. Alfsnes, H. Homberset, S. A. Frye, T. Davidsen, and T. Tonjum. 2009. Characterization of the meningococcal DNA glycosylase Fpg involved in base excision repair. BMC Microbiol. 9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Woude, M. W., and A. J. Baumler. 2004. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:581-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Houten, B., D. L. Croteau, M. J. DellaVecchia, H. Wang, and C. Kisker. 2005. ‘Close-fitting sleeves’: DNA damage recognition by the UvrABC nuclease system. Mutat. Res. 577:92-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, and M. M. Navia. 1999. Molecular basis of quinolone resistance acquisition in gram-negative bacteria. Rec. Res. Dev. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 3:323-344. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westmoreland, J., G. Porter, M. Radman, and M. A. Resnick. 1997. Highly mismatched molecules resembling recombination intermediates efficiently transform mismatch repair proficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 145:29-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zahrt, T. C., and S. Maloy. 1997. Barriers to recombination between closely related bacteria: MutS and RecBCD inhibit recombination between Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella typhi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:9786-9791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]