Abstract

Bcl2-modifying factor (Bmf) is a member of the BH3-only group of proapoptotic proteins. To test the role of Bmf in vivo, we constructed mice with a series of mutated Bmf alleles that disrupt Bmf expression, prevent Bmf phosphorylation by the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) on Ser74, or mimic Bmf phosphorylation on Ser74. We report that the loss of Bmf causes defects in uterovaginal development, including an imperforate vagina and hydrometrocolpos. We also show that the phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 can contribute to a moderate increase in levels of Bmf activity. Studies of compound mutants with the related gene Bim demonstrated that Bim and Bmf exhibit partially redundant functions in vivo. Thus, developmental ablation of interdigital webbing on mouse paws and normal lymphocyte homeostasis require the cooperative activity of Bim and Bmf.

Bmf is a proapoptotic BH3-only member of the Bcl2-related protein family that is implicated in cell death caused by anoikis (23, 26, 27), arsenic trioxide (19), histone deacetylase inhibitors (33, 34), transforming growth factor β (24), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (8). Mice with a loss of Bmf expression exhibit B-cell hyperplasia and increased sensitivity to γ-radiation-induced B-cell lymphoma (14). These observations indicate that Bmf represents an important mediator of cell death signaling pathways.

The structure of Bmf includes a BH3 domain that is essential for apoptosis induction. In addition, Bmf contains a sequence motif that is required for interactions with dynein light chain 2 (DLC2), a component of the myosin V motor complex (23). The interaction of Bmf with DLC2 is required for the recruitment of Bmf to the cytoskeleton. The release of Bmf from complexes sequestered on the cytoskeleton may contribute to anoikis (23). Interestingly, this regulatory mechanism is shared by the related proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim, which interacts via a similar sequence motif with dynein light chain 1 (DLC1), a component of the dynein motor complex (22).

The similarities between Bmf and Bim include the presence of a conserved phosphorylation site (Bmf Ser74 and Bim Thr112) that is a substrate for the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) (15). Data from biochemical studies indicate that the JNK-mediated phosphorylation of Bmf and Bim may increase apoptotic activity (15). Indeed, mice with a germ line point mutation in the Bim gene (Thr112 replaced with Ala) exhibit decreased apoptosis (10). These studies indicate that Bmf and Bim may mediate, in part, proapoptotic signaling by JNK (3, 30).

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of Bmf using mouse models with germ line defects in the Bmf gene, including mice with Bmf alleles that disrupt Bmf expression, prevent Bmf phosphorylation, or mimic Bmf phosphorylation. We examined the effects of these mutations in mice with both wild-type and mutant alleles of the related gene Bim. The results of our analysis demonstrate that Bmf and Bim exhibit partially redundant functions, that phosphorylation on Ser74 is not essential for Bmf activity, and that phosphorylation on Ser74 can contribute to increased levels of Bmf activity in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Bim−/− mice (1) and wild-type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories. We described BimΔEL/ΔEL, BimT112A/T112A, and Bim3SA/3SA mice on the C57BL/6J stain background previously (10). Mice with Bmf gene mutations were constructed by using standard methods. Mouse strain 129/Svev genomic bacterial artificial chromosome clones of the Bmf gene were isolated by hybridization analysis using a random-primed Bmf cDNA probe. Targeting vectors designed to disrupt the Bmf gene (Fig. 1A) or to introduce point mutations at Ser74 (replacement with Ala or Asp) (see Fig. 3A) were constructed with a floxed Neor cassette for positive selection and a thymidine kinase cassette for negative selection by using standard techniques. Embryonic stem (ES) cells were electroporated with these vectors and selected with 200 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) and 2 μM ganciclovir (Syntex). ES cell clones identified by Southern blot analysis were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to create chimeric mice that transmitted the mutated Bmf alleles through the germ line. The floxed Neor cassette was excised by using Cre recombinase. The mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J strain (Jackson Laboratories) for 10 generations. Homozygous Bmf mutant mice were obtained by crossing heterozygous Bmf mutant animals. The mice were housed in a facility accredited by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care. The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

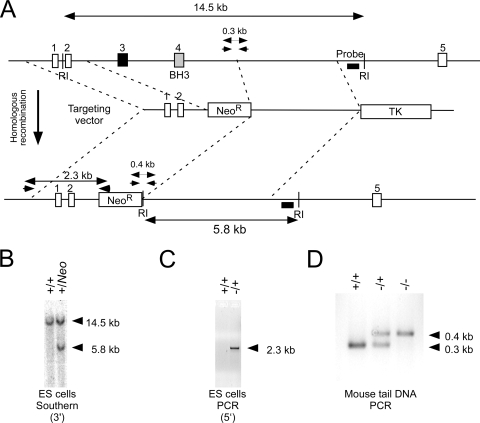

FIG. 1.

Disruption of the murine Bmf gene. (A) Strategy for construction of Bmf−/− mice. The structure of the Bmf genomic locus and the targeting vector are illustrated. EcoRI (RI) restriction sites are indicated. Homologous recombination causes the replacement of Bmf exons 3 and 4 with a Neor cassette. The PCR amplimers to confirm 5′ integration and the Southern blot probe to confirm 3′ integration of the targeting vector are indicated. The PCR amplimers employed for genotype analysis are also illustrated. (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA confirms 3′ integration of the targeting vector in ES cells. (C) PCR analysis of genomic DNA confirms the 5′ integration of the targeting vector in ES cells. (D) Genomic DNA isolated from wild-type, Bmf−/+, and Bmf−/− mice was examined by PCR analysis.

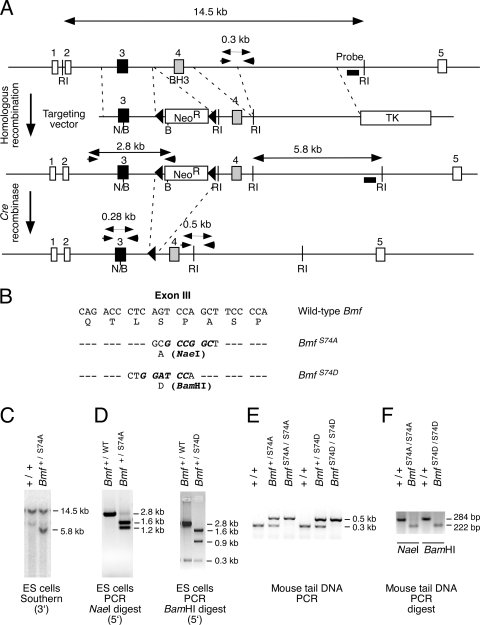

FIG. 3.

Construction of mice with disrupted Bmf phosphorylation. (A) Strategy for construction of mice with mutation of the Bmf phosphorylation site at Ser74. The structure of the Bmf genomic locus and the targeting vectors are illustrated. Homologous recombination causes the replacement of Bmf exon 3 with a mutated form of exon 3 together with the insertion of a floxed Neor resistance cassette. The PCR amplimers to confirm 5′ integration and the Southern blot probe to confirm 3′ integration of the targeting vector are indicated. The PCR amplimers employed for genotype analysis are also illustrated. Restriction endonuclease sites are also illustrated (BamHI [B], EcoRI [RI], and NaeI [N]). (B) The point mutations in exon 3 introduced by the targeting vectors are illustrated. (C and D) Homologous integration was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (3′ end) (C) and by PCR (5′ end) (D). The presence of S74A (NaeI) and S74D (BamHI) was detected by digestion of the 2.8-kb PCR product with the indicated restriction enzymes. (E) Mouse tail DNA was genotyped by PCR. (F) The genotype at codon 74 was examined by restriction digestion (NaeI and BamHI) of PCR products obtained using amplimers that span Bmf exon 3.

Genotype analysis.

The genotype at the Bmf locus was examined by Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-restricted genomic DNA by probing with a random-primed 32P-labeled probe (405 bp) that was isolated by PCR using a genomic bacterial artificial chromosome clone as the template and the amplimers 5′-TATCAGAGGCTGTGAACCCCAC-3′ and 5′-CGCAAAGCAATGTCCCTACCTATG-3′. The genotype was also determined by using a PCR-based assay. The wild-type (306-bp) and knockout (402-bp) Bmf alleles were detected by PCR analysis of genomic DNA using the amplimers 5′-AAGTAGAAACCCCTGACACCTTACC-3′, 5′-CCAACCTTTATCATTGCCCAGTC-3′, and 5′-TGGATGTGGAATGTGTGCGAG-3′. The wild-type (306-bp) and Ser74 point mutant (500-bp) Bmf alleles were detected by PCR amplification of genomic DNA with primers 5′-AAGTAGAAACCCCTGACACCTTACC-3′, 5′-CCAACCTTTATCATTGCCCAGTC-3′, and 5′-CAATGGGATGGCTTCCTGTAGTC-3′. The genotype at Bmf codon 74 was also examined (see Fig. 3E) by PCR using amplimers that span exon 3 (5′-ATGGAGCCACCTCAGTGTGTGGAGG and 5′-AGTCTCTGGGGTTCCTCTGTCAC) and restriction digestion (NaeI and BamHI) to obtain a 284-bp fragment (wild type) or a 222-bp fragment (NaeI for BmfS74A and BamHI for BmfS74D).

Tissue culture.

CD4 and CD8 T cells were purified from spleen and lymph nodes by negative selection by depleting cells expressing major histocompatibility complex class II, NK1.1, CD11b, and CD8 (for CD4 T-cell purification) or CD4 (for CD8 T-cell purification) (4, 5). The cells were cultured for 4 days in the presence of culture medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum. The number of viable cells was measured by trypan blue staining.

Flow cytometry.

Cells (1 × 106) were incubated (30 min at 4°C) with R-phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 (L3T4), allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD8α (Ly-2), and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-B220 antibodies (Pharmingen); washed with phosphate-buffered saline plus 2% bovine serum albumin; fixed in phosphate-buffered saline plus 2% formaldehyde; and examined by flow cytometry.

RESULTS

Generation of mice with germ line mutations in the Bmf gene.

We designed a targeting vector to disrupt the Bmf gene by the replacement of exon 3 and exon 4 (which encodes the BH3 domain) with a Neor cassette (Fig. 1A). This vector was electroporated into ES cells, and clones with the Bmf gene correctly targeted by homologous recombination were identified by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B) and confirmed by PCR analysis (Fig. 1C). These ES cells were employed to create chimeric mice that were bred to obtain germ line transmission of the disrupted Bmf allele. The Bmf−/+ mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J strain background (10 generations). Intercrosses of Bmf−/+ mice generated wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous knockout littermates in the expected Mendelian ratios. No obvious developmental defects in the male Bmf−/− mice were detected, although the spleen was moderately enlarged. This finding is consistent with data from a previous report that established a requirement of Bmf for B-cell homeostasis (14).

Failure of vaginal introitus development in Bmf−/− mice.

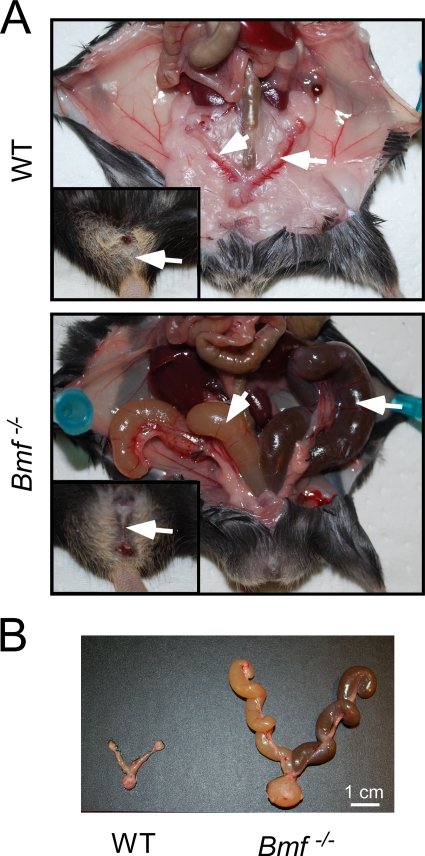

Examination of female Bmf−/− mice demonstrated defects in uterovaginal development, including an imperforate vagina and hydrometrocolpos (Fig. 2). This phenotype was observed for 22% of female Bmf−/− mice and was not detected in female Bmf−/+ mice. Previous studies demonstrated that the development of the vaginal introitus requires apoptosis of the vaginal mucosa (25) and that defects in apoptosis can result in an imperforate vagina (16, 25).

FIG. 2.

Uterovaginal abnormalities in Bmf−/− mice. (A) (Upper panel) Reproductive tract of a wild-type (WT) female mouse with a normal uterus and fallopian tubes (arrow) and vagina (insert). (Lower panel) Reproductive tract of a Bmf−/− female mouse with an imperforate vagina (insert) and hydrometrocolpos (arrow). (B) Dissected female genital tracts of wild-type and Bmf−/− female mice.

Role of JNK-mediated phosphorylation of Bmf.

The apoptotic activity of Bmf may be regulated by phosphorylation. Indeed, the phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 was previously proposed to increase apoptotic activity (15). The phosphorylation of Bmf on this site is mediated by the JNK protein kinase (15). To test the role of Bmf phosphorylation, we constructed mice with germ line point mutations in the Bmf gene.

We designed a targeting vector to introduce a point mutation at the Bmf phosphorylation site at Ser74 (replacement with Ala or Asp) together with a floxed Neor cassette in intron 3 (Fig. 3). ES cells with the correctly targeted Bmf alleles were identified by Southern blot analysis and confirmed by PCR analysis (Fig. 3). The floxed Neor cassette was excised with Cre recombinase. Three ES cell clones with a LoxP site inserted into intron 3 of the Bmf gene were selected for the creation of chimeric mice (Bmf+/S74A, Bmf+/S74D, and Bmf+/WT). Germ line transmission of the mutated Bmf alleles was obtained, and the mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J strain background (10 generations). Intercrosses of the heterozygous mice generated wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant littermates in the expected Mendelian ratios. No defects in uterovaginal development were detected in the homozygous female mutant mice (Bmf S74A/S74A, BmfS74D/S74D, and BmfWT/WT). This observation indicates that phosphorylation on Ser74 may not be essential for normal Bmf activity.

Compound mutation of the Bmf and Bim genes.

The Bmf protein is structurally similar to Bim. Both proteins contain a BH3 domain, a binding site that mediates interactions with cytoskeletal motor proteins, and sites of phosphorylation by JNK (15, 22, 23). These similarities indicate that compensation by Bim may contribute to the phenotype of Bmf mutant mice. We therefore made compound mutant mice with defects in both Bmf and Bim.

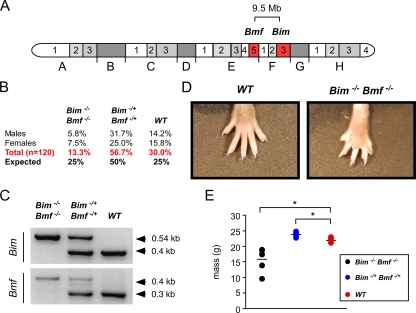

The Bmf and Bim genes are linked on mouse chromosome 2 (Fig. 4A). Progeny derived from crosses of Bim−/+ Bmf−/+ mice with Bmf−/− mice were screened for the genotype Bim−/+ Bmf−/−. Mice with the correct genotype were obtained with an efficiency of approximately 0.4%. These mice were crossed with a wild-type mouse to obtain Bim−/+ Bmf−/+ mice that have one wild-type chromosome 2 and one mutant chromosome 2. Intercrosses of these mice generated progeny with the genotypes Bim−/− Bmf−/−, Bim−/+ Bmf−/+, and Bim+/+ Bmf+/+ (Fig. 4B). Genotype analysis confirmed the presence of compound mutant Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice (Fig. 4C). The number of double-knockout mice was reduced compared with the expected Mendelian inheritance (Fig. 4B), and these mice were smaller than wild-type and Bim−/+ Bmf−/+ littermates (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Mice with compound deficiency of Bim and Bmf. (A) The location of the Bim and Bmf genes on chromosome 2 is illustrated. These genes are present within a 9.5-Mb region of mouse chromosome 2. (B) Mice with one wild-type chromosome 2 and one Bim/Bmf mutant chromosome 2 were intercrossed. The numbers of wild-type, double-heterozygous, and double-homozygous progeny are presented as the percentage of the total progeny (n = 120). The expected Mendelian ratios of progeny are also shown. (C) Genotype analysis of a wild-type mouse and compound mutant mice (Bim−/+ Bmf−/+ and Bim−/− Bmf−/−) was performed by PCR amplification of genomic DNA. (D) The webbed foot of a Bim−/− Bmf−/− mouse is compared with the foot of a wild-type mouse. (E) The masses of wild-type, Bim−/+ Bmf−/+, and Bim−/−Bmf −/− mice (aged 6 weeks) were measured. The masses of six individual mice per group are shown. The mean mass is illustrated with a horizontal line. Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05).

Examination of viable compound mutant Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice demonstrated the persistence of interdigital tissue (Fig. 4D). Interdigital webs were observed on both the front and rear paws of all Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice. No interdigital webbing was observed for Bmf−/− mice, Bim−/− mice, or Bim−/+ Bmf−/+ mice. This finding suggests that Bim and Bmf serve partially redundant functions during paw development. Interdigital webs, like those found in Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice (Fig. 4D), were also observed for Bax−/− Bim−/− mice (11) and Bax−/− Bak−/− mice (16).

We examined interdigital webbing in mice with other combinations of Bim and Bmf gene mutations, including mice lacking the sites of JNK phosphorylation on both Bmf and Bim (BimT112A/T112A BmfS74A/S74A) and mice with an acidic mutation at the site of Bmf phosphorylation by JNK (Bim−/− BmfS74D/S74D). No interdigital webbing was detected for these mice. This observation suggests that the persistence of interdigital webs requires the complete loss of function of both Bmf and Bim. This contrasts with the observed defects in uterovaginal development caused by a Bmf deficiency that were similar for Bmf−/− mice and compound mutant Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice.

Bmf and Bim are required for normal lymphocyte homeostasis.

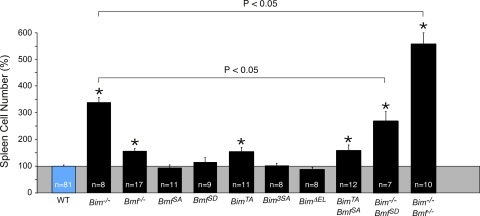

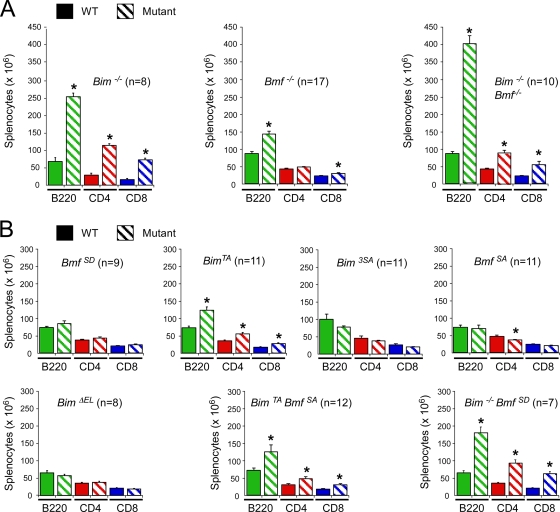

The proapoptotic genes Bmf and Bim are implicated in the homeostatic maintenance of lymphocytes (14, 28). We therefore examined splenocytes from mice with Bmf and Bim gene defects (Fig. 5 and 6). We found a large increase in the number of B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells in the spleen of Bim−/− mice, but Bmf−/− mice exhibited only a moderate increase in the number of B cells and CD8 T cells. However, no significant change in the number of splenocytes was detected in studies of mice with phosphorylation-defective Bmf proteins (BmfS74A/S74A and BmfS74D/S74D). Similarly, no increase in the number of splenocytes was detected for mice with defects in the sites of Bim phosphorylation by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase group of mitogen-activated protein kinases (BimΔEL/ΔEL and Bim3SA/3SA) (10). In contrast, a moderate increase in the number of B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells was detected for mice with a defect in Bim phosphorylation by JNK (BimT112A/T112A) (10).

FIG. 5.

Bim and Bmf deficiency causes splenomegaly. The relative numbers of splenocytes isolated from wild-type mice (100%) and mice with homozygous defects in the Bim and/or Bmf gene are presented (means ± standard deviations). Statistically significant differences between mutant mice and wild-type mice are indicated (*, P < 0.05). The figure also shows statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Bim−/− mice and Bim−/− BmfSD/SD or Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice.

FIG. 6.

Bim and Bmf deficiency causes an increase in the number of B cells and T cells in the spleen. (A and B) Spleen cells were examined by flow cytometry to identify B cells and T cells using antibodies to cell surface B220, CD4, and CD8 (means ± standard deviations). Statistically significant differences between wild-type and mutant mice are indicated (*, P > 0.05).

To test whether a mutation of the JNK phosphorylation site on Bmf (Ser74) might alter lymphocyte homeostasis in the context of altered Bim function, we examined splenocytes of mice with compound mutations in Bim and Bmf (Fig. 5 and 6). The combined loss of JNK phosphorylation of both Bim and Bmf (BimT112A/T112A BmfS74A/S74A mice) caused no further increase in the number of B cells or T cells beyond that detected for mice with defects in JNK phosphorylation of Bim alone (BimT112A/T112A mice). This observation suggested that Bmf phosphorylation on Ser74 is not essential for Bmf function.

The phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 may increase Bmf activity (15). However, a phosphomimetic mutation (replacement of Ser74 with Asp) did not significantly change (P > 0.05) the number of splenocytes in BmfS74D/S74D mice (Fig. 5). If the phosphomimetic mutation caused only a moderate increase in Bmf function, we reasoned that this might be detected in mice with a loss of Bim function. Indeed, the number of B cells and T cells in the spleen of Bim−/− BmfS74D/S74D mice was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) compared with that in the spleen of Bim−/− mice (Fig. 5 and 6). These data indicate that a phosphomimetic mutation at Ser74 on Bmf can partially suppress the effects of a Bim deficiency, consistent with the conclusion that the phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 may cause a moderate increase in levels of Bmf apoptotic activity.

The mechanism that accounts for the phosphorylation-dependent increase in Bmf activity is unclear. However, it was previously established that Bmf interacts with the myosin V motor complex that may recruit Bmf to the cytoskeleton (23). The phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 disrupts the interaction of Bmf with DLC2, a component of the myosin V complex (15). The release of Bmf from the cytoskeleton may therefore contribute to an increased level of apoptotic activity caused by Bmf phosphorylation on Ser74.

Functional cooperation of Bmf and Bim.

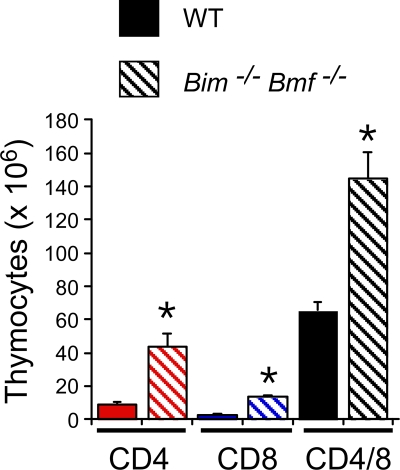

Comparison of the splenocytes from wild-type mice, Bmf−/− mice, Bim−/− mice, and Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice demonstrated that the combined loss of both Bmf and Bim caused a larger increase in cell number than did the loss of Bim or Bmf alone (Fig. 5 and 6). Flow cytometry demonstrated that Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice have increased numbers of B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells in the spleen compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). Similarly, Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice have increased numbers of CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD4/CD8 double-positive thymocytes compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 7). These observations suggest that Bmf and Bim may function cooperatively to maintain lymphocyte homeostasis.

FIG. 7.

Effect of compound mutation of Bim and Bmf on thymocytes. Thymocytes isolated from wild-type and Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice were examined by flow cytometry using antibodies to cell surface CD4 and CD8 (means ± standard deviations; n = 6). Statistically significant differences between wild-type and mutant cells are indicated (*, P < 0.05).

The effect of Bim and Bmf gene ablation to change the relative number of B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells in the spleen (Fig. 6) differs from the effect of the transgenic expression of Bcl2 in hematopoietic cells that increases the total number of splenocytes (21). Furthermore, the increased percentage of CD4/CD8 double-positive thymocytes caused by Bim and Bmf gene mutation (Fig. 7) differs from the effects of transgenic Bcl2 expression to increase the percentage of mature CD4 and CD8 T cells and decrease the percentage of immature CD4/CD8 double-positive T cells in the thymus (21). These observations indicate that Bim and Bmf exert stage-specific and cell type-dependent effects on lymphocyte homeostasis.

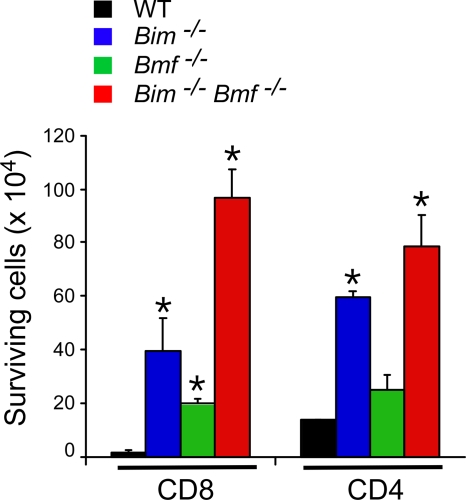

Bim and Bmf regulate survival of CD4 and CD8 T cells.

To test the relative effects of Bim and Bmf on cell survival, we examined the effect of Bim and Bmf gene disruption during in vitro culture of T cells (Fig. 8). CD4 T cells were dependent primarily upon the Bim deficiency for survival during culture in vitro (Fig. 8). In contrast, CD8 T cells were partially protected by a deficiency of either Bim or Bmf (Fig. 8). Studies of compound mutant Bim−/− Bmf−/− CD8 T cells demonstrated increased viability in vitro compared with that of Bmf−/− CD8 T cells or Bim−/− CD8 T cells (P < 0.05). These observations suggest that Bim and Bmf may cooperate to regulate the death of CD8 T cells.

FIG. 8.

Bmf and Bim deficiency causes reduced T-cell apoptosis. Purified CD4 and CD8 T cells (1 × 106 cells) were incubated in medium (4 days), and the number of viable cells was counted (means ± standard deviations; n = 5). Statistically significant differences between wild-type and mutant cells are indicated (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of proapoptotic signaling by BH3-only proteins is not fully understood. However, it is established that Bim is able to interact with antiapoptotic members of the Bcl2 family (including Bcl2 and Bcl-xl) and displace the proapoptotic effector proteins Bax and Bak (31). Bim can also interact directly with Bax to induce apoptosis (6). Both mechanisms (interaction with antiapoptotic Bcl2/Bcl-xl and proapoptotic Bax) may contribute to Bim-induced cell death in vivo (18). It is likely that Bmf may cause cell death by similar mechanisms.

The major phenotype that we detected in Bmf−/− mice was a defect in uterovaginal development, including an imperforate vagina and hydrometrocolpos. Vaginal introitus formation requires the apoptosis of the vaginal mucosa (25). Defects in apoptosis caused by the ectopic expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 (25) or the combined loss of expression of the proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak (16) also caused an imperforate vagina. Similarly, the persistence of interdigital webbing observed for Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice (Fig. 3) was found in Bax−/− Bak−/− mice (16). These data suggest that the effect of Bmf on apoptosis may be mediated by Bax/Bak and negatively regulated by Bcl2 in vivo. It is interesting that the imperforate vagina and interdigital webbing phenotypes have not been described for Apaf-1−/− mice (2, 9, 32) or Casp9−/− mice (7, 13). This finding suggests that the cytochrome c pathway may not fully account for the proapoptotic actions of Bmf. One possibility is that this form of Bmf-induced apoptosis requires functional contributions from other mitochondrial proapoptotic molecules (e.g., AIF, Smac, and Endo G).

The JNK signaling pathway is implicated in cell death (3, 30). Targets of the JNK pathway include members of the Bcl2 protein family, including the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 (20) and the proapoptotic proteins Bmf and Bim (10, 15). JNK can trigger the rapid ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Mcl-1, leading to an increased sensitivity to stress-induced apoptosis (20). In contrast, JNK phosphorylation of Bmf and Bim was previously proposed to increase apoptotic activity (15). Indeed, germ line mutation of the Bim gene (replacement of the phosphorylation site at Thr112 with Ala) causes reduced apoptosis in vivo (10). Here we demonstrate that a mutation of the site of JNK phosphorylation on Bmf (Ser74 replaced with Ala) does not cause apoptotic phenotypes that resemble the effect of a Bmf deficiency, including an imperforate vagina and (in a Bim-deficient genetic background) the persistence of interdigital webbing, or splenomegaly. These data demonstrate that the Bmf phosphorylation site at Ser74 is not essential for normal Bmf activity. Nevertheless, a phosphomimetic mutation at Ser74 was able to partially suppress splenomegaly caused by a Bim deficiency. We conclude that the phosphorylation of Bmf on Ser74 causes a moderate increase in levels of Bmf apoptotic activity in vivo.

A major conclusion of this study is that the related genes Bim and Bmf have partially redundant functions. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies that suggested cooperative actions of Bim and Bmf during cell death. Thus, it was suggested that lumen development in the breast epithelium may depend on the proapoptotic activity of both Bim (17) and Bmf (26). Similarly, both Bmf and Bim are implicated in cell death caused by infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (12) or treatment with cytotoxic drugs (19, 29). Here we demonstrate that Bmf and Bim cooperate during apoptosis induction in vivo. This is illustrated by the finding of persistent interdigital webbing in Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice but not in Bim−/− mice, Bmf−/− mice, or wild-type mice. Moreover, the splenomegaly present in Bim−/− Bmf−/− mice was significantly greater than that in Bim−/− mice, Bmf−/− mice, or wild-type mice. Together, these data demonstrate functional cooperation between the proapoptotic proteins Bim and Bmf in vivo.

In conclusion, the results of our analysis demonstrate that Bmf and Bim exhibit partially redundant functions, that phosphorylation on Ser74 is not essential for Bmf activity, and that phosphorylation on Ser74 can contribute to increased Bmf activity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Jones for blastocyst injections; Linda Evangelista for ES cell culture; Tammy Barrett, Judith Reilly, Linda Lesco, and Vicky Benoit for expert technical assistance; and Kathy Gemme for administrative assistance.

These studies were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Core facilities were supported by the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center of the University of Massachusetts (grant P30-DK52530). R.A.F. and R.J.D. are Investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouillet, P., D. Metcalf, D. C. Huang, D. M. Tarlinton, T. W. Kay, F. Kontgen, J. M. Adams, and A. Strasser. 1999. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science 286:1735-1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cecconi, F., G. Alvarez-Bolado, B. I. Meyer, K. A. Roth, and P. Gruss. 1998. Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development. Cell 94:727-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, R. J. 2000. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 103:239-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diehl, S., C. W. Chow, L. Weiss, A. Palmetshofer, T. Twardzik, L. Rounds, E. Serfling, R. J. Davis, J. Anguita, and M. Rincon. 2002. Induction of NFATc2 expression by interleukin 6 promotes T helper type 2 differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 196:39-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farley, N., G. Pedraza-Alva, D. Serrano-Gomez, V. Nagaleekar, A. Aronshtam, T. Krahl, T. Thornton, and M. Rincon. 2006. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates the Fas-induced mitochondrial death pathway in CD8+ T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:2118-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavathiotis, E., M. Suzuki, M. L. Davis, K. Pitter, G. H. Bird, S. G. Katz, H. C. Tu, H. Kim, E. H. Cheng, N. Tjandra, and L. D. Walensky. 2008. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature 455:1076-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakem, R., A. Hakem, G. S. Duncan, J. T. Henderson, M. Woo, M. S. Soengas, A. Elia, J. L. de la Pompa, D. Kagi, W. Khoo, J. Potter, R. Yoshida, S. A. Kaufman, S. W. Lowe, J. M. Penninger, and T. W. Mak. 1998. Differential requirement for caspase 9 in apoptotic pathways in vivo. Cell 94:339-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hitomi, J., D. E. Christofferson, A. Ng, J. Yao, A. Degterev, R. J. Xavier, and J. Yuan. 2008. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell 135:1311-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honarpour, N., C. Du, J. A. Richardson, R. E. Hammer, X. Wang, and J. Herz. 2000. Adult Apaf-1-deficient mice exhibit male infertility. Dev. Biol. 218:248-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubner, A., T. Barrett, R. A. Flavell, and R. J. Davis. 2008. Multisite phosphorylation regulates Bim stability and apoptotic activity. Mol. Cell 30:415-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutcheson, J., J. C. Scatizzi, E. Bickel, N. J. Brown, P. Bouillet, A. Strasser, and H. Perlman. 2005. Combined loss of proapoptotic genes Bak or Bax with Bim synergizes to cause defects in hematopoiesis and in thymocyte apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 201:1949-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepp, O., K. Gottschalk, Y. Churin, K. Rajalingam, V. Brinkmann, N. Machuy, G. Kroemer, and T. Rudel. 2009. Bim and Bmf synergize to induce apoptosis in Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuida, K., T. F. Haydar, C. Y. Kuan, Y. Gu, C. Taya, H. Karasuyama, M. S. Su, P. Rakic, and R. A. Flavell. 1998. Reduced apoptosis and cytochrome c-mediated caspase activation in mice lacking caspase 9. Cell 94:325-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labi, V., M. Erlacher, S. Kiessling, C. Manzl, A. Frenzel, L. O'Reilly, A. Strasser, and A. Villunger. 2008. Loss of the BH3-only protein Bmf impairs B cell homeostasis and accelerates gamma irradiation-induced thymic lymphoma development. J. Exp. Med. 205:641-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei, K., and R. J. Davis. 2003. JNK phosphorylation of Bim-related members of the Bcl2 family induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:2432-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsten, T., A. J. Ross, A. King, W. X. Zong, J. C. Rathmell, H. A. Shiels, E. Ulrich, K. G. Waymire, P. Mahar, K. Frauwirth, Y. Chen, M. Wei, V. M. Eng, D. M. Adelman, M. C. Simon, A. Ma, J. A. Golden, G. Evan, S. J. Korsmeyer, G. R. MacGregor, and C. B. Thompson. 2000. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol. Cell 6:1389-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailleux, A. A., M. Overholtzer, T. Schmelzle, P. Bouillet, A. Strasser, and J. S. Brugge. 2007. BIM regulates apoptosis during mammary ductal morphogenesis, and its absence reveals alternative cell death mechanisms. Dev. Cell 12:221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merino, D., M. Giam, P. D. Hughes, O. M. Siggs, K. Heger, L. A. O'Reilly, J. M. Adams, A. Strasser, E. F. Lee, W. D. Fairlie, and P. Bouillet. 2009. The role of BH3-only protein Bim extends beyond inhibiting Bcl-2-like prosurvival proteins. J. Cell Biol. 186:355-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales, A. A., D. Gutman, K. P. Lee, and L. H. Boise. 2008. BH3-only proteins Noxa, Bmf, and Bim are necessary for arsenic trioxide-induced cell death in myeloma. Blood 111:5152-5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morel, C., S. Carlson, F. M. White, and R. J. Davis. 2009. Mcl-1 integrates the opposing actions of signaling pathways that mediate survival and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:3845-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogilvy, S., D. Metcalf, C. G. Print, M. L. Bath, A. W. Harris, and J. M. Adams. 1999. Constitutive Bcl-2 expression throughout the hematopoietic compartment affects multiple lineages and enhances progenitor cell survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:14943-14948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puthalakath, H., D. C. Huang, L. A. O'Reilly, S. M. King, and A. Strasser. 1999. The proapoptotic activity of the Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by interaction with the dynein motor complex. Mol. Cell 3:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puthalakath, H., A. Villunger, L. A. O'Reilly, J. G. Beaumont, L. Coultas, R. E. Cheney, D. C. Huang, and A. Strasser. 2001. Bmf: a proapoptotic BH3-only protein regulated by interaction with the myosin V actin motor complex, activated by anoikis. Science 293:1829-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramjaun, A. R., S. Tomlinson, A. Eddaoudi, and J. Downward. 2007. Upregulation of two BH3-only proteins, Bmf and Bim, during TGF beta-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 26:970-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez, I., K. Araki, K. Khatib, J. C. Martinou, and P. Vassalli. 1997. Mouse vaginal opening is an apoptosis-dependent process which can be prevented by the overexpression of Bcl2. Dev. Biol. 184:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmelzle, T., A. A. Mailleux, M. Overholtzer, J. S. Carroll, N. L. Solimini, E. S. Lightcap, O. P. Veiby, and J. S. Brugge. 2007. Functional role and oncogene-regulated expression of the BH3-only factor Bmf in mammary epithelial anoikis and morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:3787-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Show, M. D., C. M. Hill, M. D. Anway, W. W. Wright, and B. R. Zirkin. 2008. Phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (MAPK8) is associated with germ cell apoptosis and redistribution of the Bcl2-modifying factor (BMF). J. Androl. 29:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strasser, A., H. Puthalakath, P. Bouillet, D. C. Huang, L. O'Connor, L. A. O'Reilly, L. Cullen, S. Cory, and J. M. Adams. 2000. The role of bim, a proapoptotic BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family in cell-death control. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 917:541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanBrocklin, M. W., M. Verhaegen, M. S. Soengas, and S. L. Holmen. 2009. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition induces translocation of Bmf to promote apoptosis in melanoma. Cancer Res. 69:1985-1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weston, C. R., and R. J. Davis. 2007. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19:142-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willis, S. N., J. I. Fletcher, T. Kaufmann, M. F. van Delft, L. Chen, P. E. Czabotar, H. Ierino, E. F. Lee, W. D. Fairlie, P. Bouillet, A. Strasser, R. M. Kluck, J. M. Adams, and D. C. Huang. 2007. Apoptosis initiated when BH3 ligands engage multiple Bcl-2 homologs, not Bax or Bak. Science 315:856-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida, H., Y. Y. Kong, R. Yoshida, A. J. Elia, A. Hakem, R. Hakem, J. M. Penninger, and T. W. Mak. 1998. Apaf1 is required for mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis and brain development. Cell 94:739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, Y., M. Adachi, R. Kawamura, and K. Imai. 2006. Bmf is a possible mediator in histone deacetylase inhibitors FK228 and CBHA-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 13:129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, Y., M. Adachi, R. Kawamura, H. C. Zou, K. Imai, M. Hareyama, and Y. Shinomura. 2006. Bmf contributes to histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated enhancing effects on apoptosis after ionizing radiation. Apoptosis 11:1349-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]