Abstract

Silver nitrate and aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) are often used to inhibit perception and biosynthesis, respectively, of the phytohormone ethylene. In the course of exploring the genetic basis of the extensive interactions between ethylene and auxin, we compared the effects of silver nitrate (AgNO3) and AVG on auxin responsiveness. We found that although AgNO3 dramatically decreased root indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) responsiveness in inhibition of root elongation, promotion of DR5-β-glucuronidase activity, and reduction of Aux/IAA protein levels, AVG had more mild effects. Moreover, we found that that silver ions, but not AVG, enhanced IAA efflux similarly in root tips of both the wild type and mutants with blocked ethylene responses, indicating that this enhancement was independent of ethylene signaling. Our results suggest that the promotion of IAA efflux by silver ions is independent of the effects of silver ions on ethylene perception. Although the molecular details of this enhancement remain unknown, our finding that silver ions can promote IAA efflux in addition to blocking ethylene signaling suggest that caution is warranted in interpreting studies using AgNO3 to block ethylene signaling in roots.

INTRODUCTION

The phytohormones auxin and ethylene regulate many aspects of plant growth and development. Auxin directs embryonic patterning, root and stem elongation, lateral organ development, and leaf expansion, whereas ethylene modulates fruit ripening, senescence, seed germination, abscission, and stress responses (reviewed in Davies, 2004).

Ethylene synthesis is controlled by the activity of the rate-limiting 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS) enzymes. Several ACS proteins, such as ACS5/ETHYLENE OVERPRODUCER2 (ETO2), are posttranscriptionally regulated by the ETO1 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Loss-of-function eto1 mutations and gain-of-function acs5/eto2 mutations confer ethylene overproduction, which results in short hypocotyls in dark-grown seedlings and short roots in light-grown seedlings (Figure 1A; reviewed in Chae and Kieber, 2005). Ethylene is perceived by transmembrane histidine kinase receptors that use a copper cofactor for ethylene binding (reviewed in Benavente and Alonso, 2006). ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2 (EIN2) acts downstream of ethylene perception and is required for ethylene response (Alonso et al., 1999).

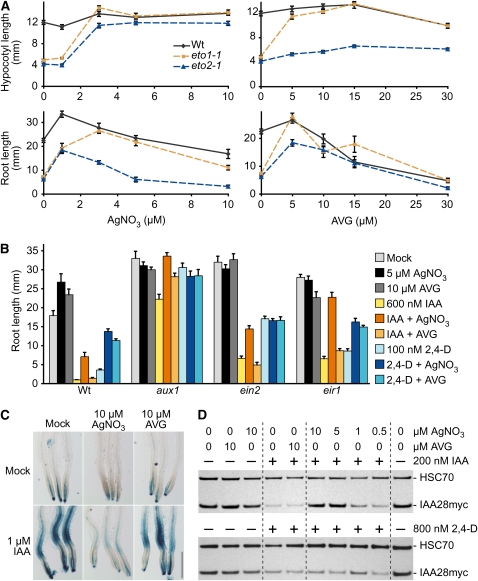

Figure 1.

AgNO3 Dampens IAA Responses in Roots.

(A) Silver nitrate and AVG are similarly effective in restoring eto1 mutant phenotypes. Wild-type (Col-0), eto1-1, and eto2-1 seedlings were grown on medium supplemented with various concentrations of AgNO3 or AVG. Hypocotyls were measured 4 d after transfer of 1-d-old seedlings to the dark (top panels). Primary roots of 8-d-old seedlings were measured after growth under continuous white light (bottom panels). Error bars represent se (n = 12).

(B) Root elongation inhibition response of the wild type (Col-0), aux1-7, ein2-1, and eir1-1 to IAA and 2,4-D in the presence and absence of AgNO3 or AVG. Primary root lengths of 8-d-old seedlings grown under continuous yellow-filtered light on mock (ethanol)-supplemented medium or medium supplemented with 600 nM IAA or 100 nM 2,4-D with or without 5 μM AgNO3 or 10 μM AVG are shown. Error bars represent se (n ≥ 12).

(C) Silver nitrate decreases IAA-induced DR5-GUS expression. Eight-day-old light-grown wild-type (Col-0) seedlings carrying the DR5-GUS transgene (Ulmasov et al., 1997) were mock treated or treated with 1 μM IAA for 2 h in medium lacking or containing 10 μM AgNO3 or 10 μM AVG and then stained for GUS activity. Bar = 0.5 mm.

(D) Silver nitrate decreases IAA-induced IAA28myc degradation. Ten-day-old wild-type (Col-0) seedlings carrying the IAA28myc construct (Strader et al., 2008a) were treated for 10 min with the indicated combinations of IAA (top panel), 2,4-D (bottom panel), AgNO3, and AVG in liquid media. Anti-myc and anti-HSC70 antibodies were used to detect IAA28myc and HSC70 (loading control), respectively, on immunoblots of protein prepared from roots of treated seedlings.

Extensive crosstalk exists between ethylene and auxin at the levels of synthesis, signaling, and transport. Ethylene stimulates synthesis of the auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (Ruzicka et al., 2007; Swarup et al., 2007), and auxin stimulates ethylene synthesis by increasing ACS transcription (reviewed in Yang and Hoffman, 1984; Tsuchisaka and Theologis, 2004). Many ethylene signaling mutants are also auxin resistant, and many auxin signaling mutants are also ethylene resistant (Stepanova et al., 2007), suggesting that some facets of auxin response require ethylene response and some aspects of ethylene response require auxin response. In further support of this interconnection, mutants with decreased IAA synthesis are mildly ethylene resistant (Stepanova et al., 2005, 2008). In addition to effects on synthesis and signaling, ethylene affects auxin transport. Ethylene inhibits polar auxin transport in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) stem sections and pea (Pisum sativum) epicotyls (Burg and Burg, 1966; Morgan and Gausman, 1966) and increases acropetal and basipetal [3H]-IAA transport in Arabidopsis thaliana roots (Negi et al., 2008). Moreover, root ethylene responses require basipetal auxin transport (Ruzicka et al., 2007).

Two compounds commonly used to differentiate between blocking ethylene biosynthesis and response are aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) and silver nitrate (AgNO3). AVG, an inhibitor of pyridoxal phosphate-mediated reactions, decreases ethylene production (Adams and Yang, 1977) by inhibiting ACS activity (Yang and Hoffman, 1984). The 1976 discovery that silver ions block ethylene responses (Beyer, 1976) has led to extensive use of AgNO3 for both agronomic and research purposes. Ag+ is thought to occupy the copper binding site of ethylene receptors and interact with ethylene but inhibits the ethylene response (Rodriguez et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2002; Binder et al., 2007). Either silver or AVG can restore eto1-1 root and hypocotyl elongation (Figure 1A; Guzman and Ecker, 1990). In this study, we present evidence suggesting that AgNO3 promotes IAA efflux in roots and that this promotion acts independently of AgNO3 effects in blocking ethylene response.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A point mutation of E1-CONJUGATING ENZYME-RELATED1 (ECR1) confers both indole-3-propionic acid resistance and certain ethylene overproduction phenotypes (Woodward et al., 2007). Blocking ethylene response with AgNO3 was required to reveal that ecr1 was resistant not only to indole-3-propionic acid but also to IAA (Woodward et al., 2007). Intriguingly, much higher IAA levels were required to inhibit wild-type root elongation in the presence of AgNO3 (Woodward et al., 2007), suggesting that part of the reduced root elongation in response to exogenous IAA might be attributable to the inhibitory effects of ethylene synthesized following IAA treatment.

We further explored this hypothesis by examining the impact of pharmacological ethylene blockers on auxin responsiveness of the wild type, the auxin influx mutant aux1 (Marchant et al., 1999), the ethylene response mutant ein2 (Alonso et al., 1999), and the auxin efflux mutant eir1 (Luschnig et al., 1998). We assayed root elongation inhibition responses to IAA and the auxinic compound 2,4-D in the presence and absence of AVG or AgNO3. We expected that either blocking ethylene production with AVG or blocking ethylene response with AgNO3 would similarly reduce auxin responsiveness. Instead, we found that AgNO3 blocked wild-type IAA response more effectively than AVG (Figure 1B). AgNO3 and AVG were similarly effective in restoring hypocotyl and root elongation to eto1-1 (Figure 1A), suggesting that both were active in our conditions, and similarly reduced wild-type root elongation inhibition in response to 2,4-D (Figure 1B). We concluded that the interaction between AgNO3 and IAA is different from that of AgNO3 and 2,4-D.

We expected that AgNO3 and AVG would not affect the auxin responsiveness of ein2 because ein2 is completely ethylene insensitive (Alonso et al., 1999) and presumably would not respond to ethylene produced in response to auxin treatment. Indeed, ein2 resistance to the auxin analog 2,4-D was unaffected by AgNO3 or AVG (Figure 1B). However, AgNO3, but not AVG, reduced ein2 response to IAA (Figure 1B), suggesting that AgNO3 decreased IAA response independently of ethylene response. Similarly, the diminished IAA sensitivity of eir1/pin2 in the presence of AgNO3 but not AVG (Figure 1B) suggested that AgNO3 did not reduce IAA sensitivity by enhancing PIN2-mediated IAA efflux. Although nearly insensitive to IAA at the concentration tested, aux1 also displayed further decreased IAA sensitivity in the presence of AgNO3 (Figure 1B), suggesting that AgNO3 reduced IAA sensitivity without reducing AUX1-mediated IAA influx.

To determine the site in the IAA response pathway that was impacted by silver ions, we examined two auxin-responsive reporters, DR5-β-glucuronidase (GUS), which monitors auxin-responsive transcription (Ulmasov et al., 1997), and IAA28myc, which monitors auxin-stimulated protein degradation (Strader et al., 2008a). We found that AgNO3 greatly reduced the ability of IAA to induce the DR5-GUS transcriptional reporter in root tips (Figure 1C), whereas AVG had only a mild effect (Figure 1C), suggesting that AgNO3 dampened auxin response upstream of auxin-responsive gene expression. Because Aux/IAA proteins repress auxin-induced gene expression, we examined the effect of AgNO3 and AVG on IAA-induced IAA28myc destabilization in roots. A 10-min IAA treatment is sufficient to dramatically decrease IAA28myc levels (Figure 1D; Strader et al., 2008a). We found that 10 μM AVG had no apparent effect on IAA-induced instability of IAA28myc in this assay (Figure 1D). By contrast, including AgNO3 with the applied IAA reduced the IAA effects on IAA28myc levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1D), suggesting that AgNO3 acted upstream of Aux/IAA destabilization. Because the interaction between AgNO3 and IAA is different from that of AgNO3 and 2,4-D (Figure 1B), we also examined the effect of AgNO3 or AVG on 2,4-D-induced IAA28myc destabilization. We found that neither inhibitor had an apparent effect on 2,4-D-induced stability of IAA28myc in this assay (Figure 1D). Because Aux/IAA destabilization is very rapid and because the Aux/IAA protein itself forms a part of the IAA receptor complex (Tan et al., 2007), these data suggested that the AgNO3 effect on IAA28myc levels was not solely due to the ability of silver ions to block ethylene signaling.

Because our data suggested that the effect of silver ions on root IAA responsiveness was upstream of the known signaling components, we examined the effect of AgNO3 on [3H]-IAA accumulation in an excised root tip assay (Ito and Gray, 2006; Strader et al., 2008b; Strader and Bartel, 2009). We found that AgNO3, but not KNO3 (Figure 2A) or AVG (Figure 2B), dramatically decreased [3H]-IAA accumulation following a 1-h incubation. We also examined the effect of AgNO3 and AVG on [3H]-IAA accumulation in aux1-7, ein2-1, and eir1-1 root tips. We found that aux1-7, as previously reported (Strader et al., 2008a), accumulated less [3H]-IAA than the wild type in this assay, consistent with the role of AUX1 in IAA uptake. Like the wild type, aux1 root tips accumulated less [3H]-IAA in the presence of AgNO3 (Figure 2B), suggesting that AgNO3 does not reduce [3H]-IAA accumulation by decreasing AUX1-mediated IAA influx. ein2 (Figure 2B), etr1 (Figure 2C), and ers2 (Figure 2C) root tips accumulated similar [3H]-IAA as the wild type and similarly reduced [3H]-IAA accumulation in the presence of AgNO3, indicating that an intact ethylene signaling pathway was not necessary for normal [3H]-IAA accumulation and that AgNO3 does not reduce [3H]-IAA accumulation by blocking ethylene signaling. We also tested mutants defective in various proteins implicated in auxin efflux and found that eir1, pen3, mdr1, mdr4, pgp1, and pgp1 mdr1 root tips responded like the wild type to AgNO3 by accumulating less [3H]-IAA (Figures 2C and 2D), suggesting that AgNO3 does not reduce [3H]-IAA accumulation by increasing IAA efflux by EIR1/PIN2, PEN3/PDR8/ABCG36, MDR1/ABCB19, MDR4/ABCB4, or PGP1/ABCB1.

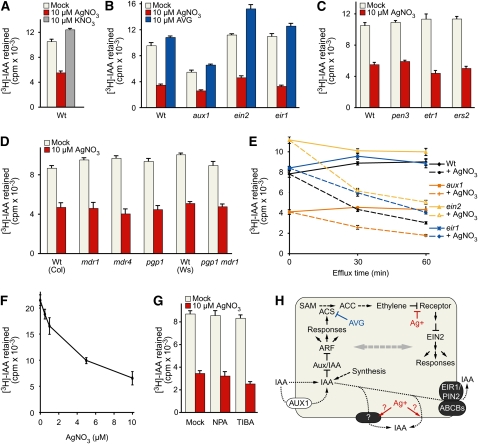

Figure 2.

AgNO3 Promotes [3H]-IAA Efflux from Root Tips.

(A) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt) seedlings were incubated for 1 h in uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA, 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM AgNO3, or 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM KNO3, rinsed three times with uptake buffer, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(B) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt), aux1-7, ein2-1, and eir1-1 seedlings were incubated for 1 h in uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA, 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM AgNO3, or 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM AVG, rinsed three times with uptake buffer, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(C) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt), pen3-4, etr1-1, and ers2-1 seedlings were incubated for 1 h in uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA or 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM AgNO3, rinsed three times with uptake buffer, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(D) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt), mdr1-3, mdr4-1, pgp1-100, Ws-2 (Wt), and pgp1-1 mdr1-1 (in the Wassilewskija background) seedlings were incubated for 1 h in uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA or 25 nM [3H]-IAA and 10 μM AgNO3, rinsed three times with uptake buffer, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(E) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt), aux1-7, ein2-1, and eir1-1 seedlings were incubated for 1 h in 80 μL uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA, rinsed three times, incubated for an additional 30 or 60 min in 400 μL buffer with or without 10 μM AgNO3 or 10 μM AVG, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(F) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt) seedlings were incubated for 1 h in 80 μL uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA, rinsed three times, incubated for an additional 1 h in 400 μL buffer containing 0, 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 μM AgNO3, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

(G) Root tips of Col-0 (Wt) seedlings were incubated for 1 h in 80 μL uptake buffer containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA, rinsed three times, incubated for an additional 30 min in 400 μL buffer containing mock (ethanol), 100 μM NPA, or 100 μM TIBA, and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

For all experiments, data are from six replicates of assays with five root tips (5-mm sections) of 8-d-old light-grown seedlings of each genotype. Error bars represent se.

(H) A model for the effects on AgNO3 and AVG on auxin and ethylene signaling. IAA is transported into cells by AUX1 and related transporters and via diffusion through the membrane and is removed by effluxers such as EIR1/PIN2 and the ABCB proteins. In the cell, IAA stimulates the degradation of Aux/IAA proteins to relieve repression of auxin-responsive transcription (reviewed in Woodward and Bartel, 2005), leading to various responses, including induction of ACS transcription and ethylene production (reviewed in Yang and Hoffman, 1984; Tsuchisaka and Theologis, 2004). ACS activity can be blocked with AVG (Yang and Hoffman, 1984), and signaling by ethylene receptors, such as ETR1 and ERS2, can be blocked with Ag+ (Rodriguez et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2002; Binder et al., 2007). EIN2 is required for ethylene signaling and acts downstream of ethylene perception (Alonso et al., 1999). The double-headed gray arrow represents extensive crosstalk between auxin and ethylene pathways. Solid black arrows depict signaling, dashed black arrows depict hormone synthesis, and dotted black arrows represent transport. Silver ions appear to stimulate IAA efflux independently of known IAA efflux components, such as EIR1/PIN2 and the ABCB proteins. Whether the Ag+-stimulated IAA efflux is transporter mediated or results from an effect on membrane permeability is unknown.

During the 1-h labeling period, the amount of [3H]-IAA accumulated within root tips reflects the balance of [3H]-IAA influx and efflux. To separate influx from efflux, we incubated root tips in [3H]-IAA for 1 h, rinsed the root tips thoroughly with buffer, and then incubated the root tips for additional time in a large buffer volume (to minimize reuptake of effluxed [3H]-IAA) with or without 10 μM AgNO3. We found that the effect of AgNO3 when provided only during an efflux period (Figure 2E) was similar to its effects when provided continually (Figures 2A to 2D), suggesting that AgNO3 reduced [3H]-IAA accumulation by increasing [3H]-IAA efflux. We also found that the effect of AgNO3 on [3H]-IAA efflux was dose dependent in a 1-h efflux period (Figure 2F). To determine whether auxin transport inhibitors could alter AgNO3-responsive [3H]-IAA efflux, we examined the effects of including 1-N-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) or 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) during the efflux period. We found that inclusion of NPA or TIBA did not affect the accumulation of [3H]-IAA with or without AgNO3 in this assay (Figure 2G).

Our data suggest that, in addition to blocking ethylene responsiveness, silver ions can promote IAA efflux and thereby reduce accumulation of applied IAA in roots. This observation could explain why AgNO3 reduces the efficacy of IAA treatment in root elongation inhibition (Figure 1B), gene expression (Figure 1C), and Aux/IAA degradation (Figure 1D) bioassays. The AgNO3 promotion of IAA efflux appears to be independent of AUX1, EIN2, and known auxin efflux proteins (Figure 2) and thus may be mediated by an unidentified auxin effluxer or an effect on membrane permeability. Although the molecular details of this enhancement remain unknown, our finding that silver ions can impact IAA efflux independent of effects on ethylene signaling suggest that caution is warranted in interpreting studies using AgNO3 to dissect the extensive interactions between ethylene and auxin pathways in roots.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Phenotypic Assays

The Columbia (Col-0) accession of Arabidopsis thaliana was used as the wild type for all experiments, unless noted otherwise. Surface-sterilized seeds (Last and Fink, 1988) were plated on PN (plant nutrient medium; Haughn and Somerville, 1986) supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) sucrose (PNS) and solidified with 0.6% (w/v) agar and grown under continuous illumination at 22°C. Hormone stocks were dissolved in ethanol; AgNO3 and AVG stocks were dissolved in water.

For hypocotyl elongation assays, seeds were plated on media supplemented with various concentrations of AgNO3 or AVG. After 1 d in the light, plates were wrapped with aluminum foil and incubated for an additional 4 d in the dark before lengths of hypocotyls were measured. For AgNO3- or AVG-responsive root elongation assays, seedlings were grown for 8 d under continuous illumination on media supplemented with various concentrations of AgNO3 or AVG, and the lengths of primary roots were measured.

For auxin-responsive root elongation assays, seedlings were grown for 8 d under continuous illumination through yellow long-pass filters (yellow 2208, 1/8-inch-thick plexiglass; A&C Plastics) to slow indolic compound breakdown (Stasinopoulos and Hangarter, 1990) on PNS with the indicated auxin, AgNO3, or AVG concentrations, and the lengths of primary roots were measured.

For GUS activity assays, 8-d-old light-grown seedlings were removed from PNS plates and treated for 2 h in liquid PN media containing various combinations of mock (ethanol) treatment, 1 μM IAA, 10 μM AgNO3, and 10 μM AVG and then stained for GUS activity overnight (Bartel and Fink, 1994). Seedlings were then mounted and imaged using a dissecting microscope.

To visualize IAA28myc, eight 10-d-old wild-type (Col-0) seedlings carrying the IAA28myc construct (Strader et al., 2008a) were removed from PNS medium and floated in liquid PN supplemented with either ethanol, 200 nM IAA, or 800 nM 2,4-D and the indicated concentrations of AgNO3 or AVG. After 10 min, roots from these eight seedlings were excised and protein was extracted and separated by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris; Invitrogen). Protein was transferred to a Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and analyzed by immunoblotting as previously described (Strader et al., 2008a). After incubation overnight with a 1:500 dilution of anti-c-Myc (monoclonal 9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology SC-40) and a 1:250,000 dilution of anti-HSC70 (Stressgen Bioreagents SPA-817) antibodies, membranes were rinsed three times and incubated for 4 h in a 1:5000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rinsed again, and then visualized using LumiGLO reagent (Cell Signaling) and detection using x-ray film (ISC BioExpress). Multiple film exposures from each biological replicate showed similar results, and data shown are representative of at least three biological replicates of each experiment.

Auxin Accumulation Assays

For auxin accumulation assays, 5-mm sections of root tips from 8-d-old light-grown seedlings were excised and incubated for 10 min at room temperature in 40 μL uptake buffer (20 mM MES, 10 mM sucrose, and 0.5 mM CaSO4, pH 5.6) supplemented with the indicated concentrations of KNO3, AgNO3, or AVG. Additional uptake buffer supplemented with the indicated concentrations of KNO3, AgNO3, or AVG containing radiolabeled IAA was added for a final volume of 80 μL containing 25 nM [3H]-IAA (20 Ci/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals). After 1 h at room temperature, root tips were rinsed with three changes of uptake buffer supplemented with the indicated concentrations of KNO3, AgNO3, or AVG and then removed and analyzed by scintillation counting in 3 mL of Cytoscint scintillation cocktail (Fisher Scientific).

For auxin retention assays, root tips were incubated as described above. After 1 h at room temperature, root tips were rinsed with three changes of uptake buffer and placed in 400 μL fresh uptake buffer supplemented with the indicated concentrations of KNO3, AgNO3, AVG, NPA, or TIBA. After 30 or 60 min incubation at room temperature, root tips were removed and analyzed by scintillation counting.

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifiers of genes used in this study are as follows: AUX1, At2g38120; EIN2, At5g03280; EIR1/PIN2, At5g57090; ERS2, At1g04310; ETO1, At3g51770; ETO2/ACS5, At5g65800; ETR1, At1g66340; MDR1/ABCB19, At3g28860; MDR4/ABCB4, At2g47000; PEN3/PDR8/ABCG36, At1g59870; and PGP1/ABCB1, At2g36910.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Woodward for valuable discussions; Matthew Lingard, Naxhiely Martinez, and Sarah Ratzel for critical comments on the manuscript; Mark Estelle for aux1-7; Edgar Spalding for mdr1-3, mdr4-1, pgp1-100, and pgp1-1 mdr1-1; and the ABRC for ein2-1, eir1-1, ers2-1, etr1-1, and pen3-4. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB-0745122 to B.B.), the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1309 to B.B.), and the National Institutes of Health (F32-GM075689 to L.C.S.). E.R.B. was supported by an American Society of Plant Biologists' Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship and an Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professor's Grant (52005717 to B.B.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Bonnie Bartel (bartel@rice.edu).

References

- Adams, D.O., and Yang, S.F. (1977). Methionine metabolism in apple tissue: Implication of S-adenosylmethionine as an intermediate in the conversion of methionine to ethylene. Plant Physiol. 60 892–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.M., Hirayama, T., Roman, G., Nourizadeh, S., and Ecker, J.R. (1999). EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress response in Arabidopsis. Science 284 2148–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, B., and Fink, G.R. (1994). Differential regulation of an auxin-producing nitrilase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 6649–6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavente, L.M., and Alonso, J.M. (2006). Molecular mechanisms of ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biosyst. 2 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, E.M. (1976). A potent inhibitor of ethylene action in plants. Plant Physiol. 58 268–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder, B.M., Rodriguez, F.I., Bleecker, A.B., and Patterson, S.E. (2007). The effects of Group 11 transition metals, including gold, on ethylene binding to the ETR1 receptor and growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 581 5105–5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg, S.P., and Burg, E.A. (1966). The interaction between auxin and ethylene and its role in plant growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 55 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae, H.S., and Kieber, J.J. (2005). Eto Brute? Role of ACS turnover in regulating ethylene biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 10 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.J. (2004). Introduction. In Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! P.J. Davies, ed (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers), pp. 1–35.

- Guzman, P., and Ecker, J.R. (1990). Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughn, G.W., and Somerville, C. (1986). Sulfonylurea-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Gen. Genet. 204 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H., and Gray, W.M. (2006). A gain-of-function mutation in the Arabidopsis pleiotropic drug resistance transporter PDR9 confers resistance to auxinic herbicides. Plant Physiol. 142 63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last, R.L., and Fink, G.R. (1988). Tryptophan-requiring mutants of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 240 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luschnig, C., Gaxiola, R.A., Grisafi, P., and Fink, G.R. (1998). EIR1, a root-specific protein involved in auxin transport, is required for gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 12 2175–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, A., Kargul, J., May, S.T., Muller, P., Delbarre, A., Perrot-Rechenmann, C., and Bennett, M.J. (1999). AUX1 regulates root gravitropism in Arabidopsis by facilitating auxin uptake within root apical tissues. EMBO J. 18 2066–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P.W., and Gausman, H.W. (1966). Effects of ethylene on auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 41 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi, S., Ivanchenko, M.G., and Muday, G.K. (2008). Ethylene regulates lateral root formation and auxin transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 55 175–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, F.I., Esch, J.J., Hall, A.E., Binder, B.M., Schaller, G.E., and Bleecker, A.B. (1999). A copper cofactor for the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Science 283 996–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzicka, K., Ljung, K., Vanneste, S., Podhorska, R., Beeckman, T., Friml, J., and Benkova, E. (2007). Ethylene regulates root growth through effects on auxin biosynthesis and transport-dependent auxin distribution. Plant Cell 19 2197–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasinopoulos, T.C., and Hangarter, R.P. (1990). Preventing photochemistry in culture media by long-pass light filters alters growth of cultured tissues. Plant Physiol. 93 1365–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova, A.N., Hoyt, J.M., Hamilton, A.A., and Alonso, J.M. (2005). A link between ethylene and auxin uncovered by the characterization of two root-specific ethylene-insensitive mutants in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 2230–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova, A.N., Robertson-Hoyt, J., Yun, J., Benavente, L.M., Xie, D.Y., Dolezal, K., Schlereth, A., Jurgens, G., and Alonso, J.M. (2008). TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 133 177–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova, A.N., Yun, J., Likhacheva, A.V., and Alonso, J.M. (2007). Multilevel interactions between ethylene and auxin in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 19 2169–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader, L.C., and Bartel, B. (2009). The Arabidopsis PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE8/ABCG36 ATP binding cassette transporter modulates sensitivity to the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. Plant Cell 21 1992–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader, L.C., Monroe-Augustus, M., and Bartel, B. (2008. a). The IBR5 phosphatase promotes Arabidopsis auxin responses through a novel mechanism distinct from TIR1-mediated repressor degradation. BMC Plant Biol. 8 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader, L.C., Monroe-Augustus, M., Rogers, K.C., Lin, G.L., and Bartel, B. (2008. b). Arabidopsis iba response5 (ibr5) suppressors separate responses to various hormones. Genetics 180 2019–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup, R., Perry, P., Hagenbeek, D., Van Der Straeten, D., Beemster, G.T., Sandberg, G., Bhalerao, R., Ljung, K., and Bennett, M.J. (2007). Ethylene upregulates auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings to enhance inhibition of root cell elongation. Plant Cell 19 2186–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X., Calderon-Villalobos, L.I., Sharon, M., Zheng, C., Robinson, C.V., Estelle, M., and Zheng, N. (2007). Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchisaka, A., and Theologis, A. (2004). Unique and overlapping expression patterns among the Arabidopsis 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene family members. Plant Physiol. 136 2982–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov, T., Murfett, J., Hagen, G., and Guilfoyle, T.J. (1997). Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9 1963–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, A.W., and Bartel, B. (2005). Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 95 707–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, A.W., Ratzel, S.E., Woodward, E.E., Shamoo, Y., and Bartel, B. (2007). Mutation of E1-CONJUGATING ENZYME-RELATED1 decreases RELATED TO UBIQUITIN conjugation and alters auxin response and development. Plant Physiol. 144 976–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.F., and Hoffman, N.E. (1984). Ethylene biosynthesis and its regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 35 155–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.C., Qu, X., Mathews, D.E., and Schaller, G.E. (2002). Effect of ethylene pathway mutations upon expression of the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 130 1983–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]