Abstract

The human coronaviruses (CoVs) severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV and NL63 employ angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) for cell entry. It was shown that recombinant SARS-CoV spike protein (SARS-S) downregulates ACE2 expression and thereby promotes lung injury. Whether NL63-S exerts a similar activity is yet unknown. We found that recombinant SARS-S bound to ACE2 and induced ACE2 shedding with higher efficiency than NL63-S. Shedding most likely accounted for the previously observed ACE2 downregulation but was dispensable for viral replication. Finally, SARS-CoV but not NL63 replicated efficiently in ACE2-positive Vero cells and reduced ACE2 expression, indicating robust receptor interference in the context of SARS-CoV but not NL63 infection.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) emerged in 2002 in Guangdong province, China, and its subsequent spread to 26 countries was associated with 8,096 infections and 774 deaths (29). The human coronavirus NL63 was discovered in 2004 in the Netherlands (7, 33) and was shown to be globally distributed (2, 3, 6, 23, 31). NL63 infection seems to be acquired during childhood (2, 3, 6, 11, 23, 31) and is usually not associated with severe disease (2, 3, 6, 23, 31-33). Both SARS-CoV and NL63 employ angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as receptor for infectious entry into target cells (11, 19, 34). Several lines of evidence suggest that ACE2 plays a key role in SARS-CoV spread: (i) ACE2 is expressed on the major SARS-CoV target cells, type II pneumocytes (4, 9, 25, 30), as well as on ciliated airway epithelial cells (28), (ii) ACE2 expression in cell lines correlates with susceptibility to SARS-CoV spike protein (SARS-S)-driven entry (11, 26), and (iii) knockout of ACE2 in mice abrogates permissiveness to SARS-CoV infection (16). For NL63, ACE2 expression was also shown to correlate with susceptibility to infection (11), and the virus has been found to infect ciliated bronchial epithelial cells in culture (1, 5), but the NL63 target cells in infected patients have not been defined, and an animal model for NL63 replication has not been established.

ACE2 is a component of the renin-angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure (14, 17). In addition, Kuba and colleagues and Imai and colleagues showed that pulmonary ACE2 expression protects against experimentally induced lung injury (13, 16). Treatment of mice with soluble SARS-S reduced cell surface expression of ACE2 and thereby exacerbated experimentally induced lung disease (16), suggesting that interactions of SARS-S with its cellular receptor could promote acute lung injury in infected patients. Notably, it has recently been proposed that binding of SARS-CoV but not NL63 to ACE2 induces ACE2 shedding from the cell surface, and evidence has been presented that this process is required for cellular uptake of SARS-CoV (8). Whether ACE2 shedding is indeed a prerequisite to infectious entry and contributes to the previously observed ACE2 downregulation by SARS-S (16) remains to be determined. In addition, it is unclear if SARS-S and NL63-S differentially interfere with ACE2 expression, which might contribute to the differential pathogenicity of these viruses.

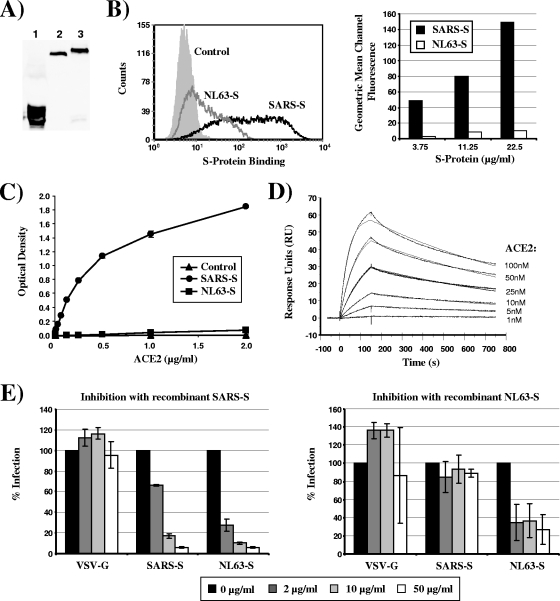

To address the questions raised above, we first investigated if SARS-S and NL63-S bind to ACE2 with different efficiencies, which could result in differential ACE2 downregulation. For this, the S1 units of the viral S proteins (SARS-S, amino acids 13 to 714; NL63-S, amino acids 16 to 741), fused to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin, were transiently expressed in 293T cells and purified from the culture supernatants by chromatography with protein A columns (Fig. 1A). Purified SARS-S bound to ACE2-expressing cells with much higher efficiency than equal amounts of NL63-S (Fig. 1B). Similarly, binding studies in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format revealed highly efficient capture of recombinant ACE2 by SARS-S, while binding of ACE2 to NL63-S was barely detectable (Fig. 1C). In addition, SARS-S binding to ACE2 was readily observed in a BIAcore system-based analysis (Fig. 1D), while NL63-S did not specifically bind to ACE2 (data not shown). Finally, preincubation of ACE2-transfected cells with recombinant SARS-S blocked subsequent infection with lentiviruses pseudotyped with SARS-S and NL63-S, while inhibition with recombinant NL63-S was much less pronounced (Fig. 1E). In summary, our results and those of previous studies (20, 22) indicate that SARS-S binds to ACE2 with higher efficiency than NL63-S.

FIG. 1.

SARS-S binds to ACE2 with higher efficiency than NL63-S. (A) For production of recombinant SARS-S and NL63-S proteins, the S1 unit of the respective proteins was fused to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin, and the soluble S proteins and the Fc control protein were transiently expressed in 293T cells. The S proteins and the Fc control protein were purified from the culture supernatants by protein A chromatography, and protein content was analyzed by Western blot analysis using an anti-human Fc antibody. Lane 1, Fc control; lane 2, SARS-S; lane 3, NL63-S. (B) 293T cells stably expressing ACE2 were incubated with SARS-S, NL63-S, and Fc control protein at a concentration of 22.5 μg/ml, and protein binding was analyzed by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). Results from a representative experiment are shown in the left panel, and the geometric mean channel fluorescence measured upon analysis of duplicate samples is shown in the right panel. (C) Binding of SARS-S and NL63-S to ACE2 was assessed by employing a sandwich ELISA. The ELISA plate was coated with anti-human Fc antibody to capture the soluble spike Fc proteins or a Fc control protein (2 μg/ml), followed by addition of different concentrations of recombinant ACE2 labeled with a FLAG tag, which was detected using an anti-FLAG antibody-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate. (D) An anti-human Fc antibody was immobilized onto a BIAcore chip surface, and SARS-S Fc protein was added. Subsequently, unbound protein was removed, and binding of different concentrations of recombinant ACE2 was assessed. The binding of the receptor was measured by a decreased angle of the surface plasma resonance (SPR), which is illustrated in response units (RU) over time. (E) 293T cells overexpressing ACE2 were incubated with the indicated concentrations of recombinant SARS-S (left) or NL63-S (right) for 1 h at 37°C and infected with lentiviruses pseudotyped with SARS-S, NL63-S, or vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G). At 72 h postinfection, the luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined using a commercially available kit. The results of a representative experiment are shown and are graphed as relative infection efficiency. Upon infection in the absence of recombinant spike protein, the following luciferase counts per second (c.p.s.) were measured: VSV-G, 3,612,752 ± 2,523,541 c.p.s.; SARS-S, 2,290,442 ± 347,006 c.p.s.; NL63-S, 168,575 ± 20,581 c.p.s.

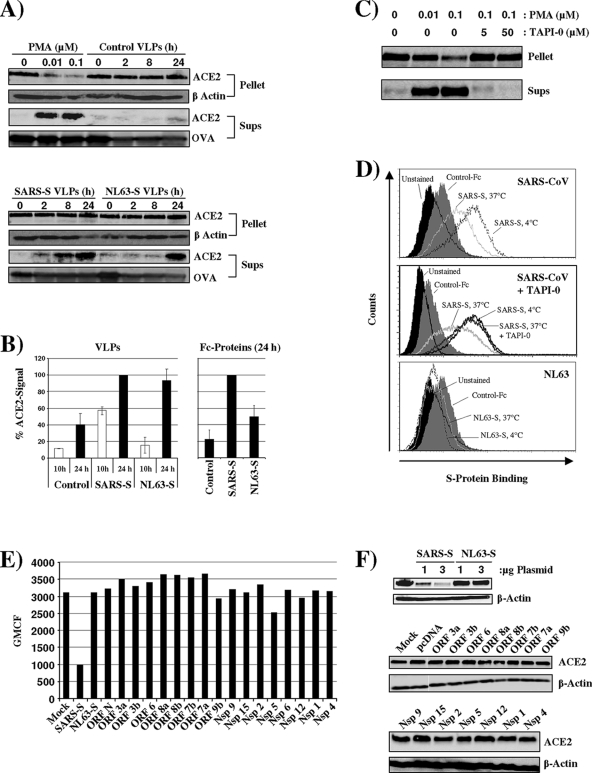

We next asked if ACE2 expression is differentially downregulated by the viral S proteins. Recent work by Haga and colleagues demonstrated that binding of recombinant and virion-associated SARS-S to ACE2 induces ACE2 shedding in a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17 (ADAM17)/tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-converting enzyme (TACE)-dependent manner (8, 18). These observations indicate that ACE2 shedding might reduce ACE2 surface expression. We therefore investigated ACE2 shedding from Vero E6 cells, which express endogenous ACE2. ACE2 expression in cell lysates and the presence of ACE2 in trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-precipitated cell culture supernatants was detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). Detection of β-actin served as a loading control for the analysis of cell lysates. For control of comparable precipitation efficiency, ovalbumin (OVA) was added to supernatants and also detected by Western blot analysis. Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) treatment induced shedding of ACE2 into the cellular supernatants and reduced the amount of cell-associated ACE2, in agreement with previous results (Fig. 2A, top) (8, 18). Incubation of cells with control virus-like particles (VLPs) bearing no viral glycoprotein did not induce ACE2 shedding. In contrast, VLPs bearing SARS-S triggered ACE2 shedding over time (Fig. 2A). The levels of cell-associated ACE2 remained constant, suggesting that ACE2 release was less efficient than release from PMA-treated cells. Notably, ACE2 shedding was also observed upon incubation of cells with VLPs bearing NL63-S, albeit the kinetics were delayed compared to cells exposed to SARS-S-bearing VLPs (Fig. 2A, bottom, and 2B). Similarly, ACE2 shedding was induced by soluble NL63-S but with lower efficiency than virion-associated protein (Fig. 2B). Collectively, SARS-S and to a lesser extent NL63-S can induce ACE2 shedding.

FIG. 2.

SARS-S but not NL63-S induces efficient ACE2 shedding. (A) Vero E6 cells were incubated for 0, 2, 8, and 24 h with VLPs harboring SARS-S, NL63-S, or control particles containing no viral glycoprotein. As a positive control for ACE2 shedding, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of PMA for 1 h. Thereafter, the supernatants were harvested, OVA was added, and the samples were precipitated with TCA. In parallel, the cells were lysed, pellets were obtained upon TCA precipitation, and cell lysates were analyzed for ACE2 expression by Western blot analysis. As precipitation and loading control, respectively, OVA content (supernatants) and β-actin expression (cell lysates) were also determined by Western blot analysis. (B) The signals obtained for ACE2 in the culture supernatants examined in panel A (left) or in the supernatants of cells treated with Fc control protein, SARS-S Fc, or NL63-S Fc protein (right) were quantified employing ImageJ software. The average of two independent experiments is shown in the left panel. The right panel depicts the average of three independent experiments. (C) To confirm the importance of TACE for ACE2 shedding, Vero E6 cells were incubated with 0.1 μM PMA in the presence of the indicated concentrations of TAPI-0, a TACE inhibitor. ACE2 shedding was analyzed as described for panel A. (D) Vero E6 cells were incubated with SARS-S for 3 h at 4°C or 37°C in the absence (top) and presence (middle) of TAPI-0. Alternatively, cells were incubated with NL63-S protein for 3 h at 4°C or 37°C (bottom). Thereafter, unbound protein was removed by washing, and protein binding was determined by FACS analysis. (E) 293T cells engineered to express high levels of ACE2 were transiently transfected with 3 μg of plasmids encoding SARS-S, NL63-S, or the indicated SARS-CoV proteins, and ACE2 surface expression was determined by FACS analysis. (F) The experiment was carried out as described in panel E. However, the cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection, and ACE2 expression in cell lysates was analyzed by Western blot analysis. Expression of β-actin was determined as a loading control.

We then assessed if shedding contributes to ACE2 downregulation. For this, we employed TAPI-0, a TACE inhibitor (24). Incubation of PMA-treated cells with TAPI-0 abrogated ACE2 release (Fig. 2C), as expected (8, 18), confirming that the compound was active at the concentrations used. If ACE2 shedding contributes to ACE2 downregulation, as previously observed by Kuba and colleagues (16), we reasoned that this process should be sensitive to inhibition by TAPI-0. Following the previously established FACS-based protocol, binding of S proteins to Vero E6 cells was analyzed at 37°C (to allow shedding) in the presence and absence of TAPI-0. In addition, binding of S proteins to Vero E6 cells at 4°C (to prevent shedding) was determined as a control. SARS-S but not a control Fc protein bound efficiently to Vero E6 cells maintained at 4°C (Fig. 2D, top). Binding of SARS-S was markedly diminished when cells were incubated at 37°C (Fig. 2D, top), in agreement with published results (16). Notably, this effect could be completely reversed by incubation of cells with TAPI-0 (Fig. 2D, middle). Thus, ACE2 shedding accounted for the reduced SARS-S binding and was most likely responsible for the diminished ACE2 surface expression previously observed under these conditions (an antibody for detection of ACE2 on Vero cells by FACS was not available for the present study) (16). In contrast, appreciable binding of NL63-S to Vero E6 cells was not observed (Fig. 2D, bottom), in agreement with the less-efficient ACE2 binding (Fig. 1) and less-efficient ACE2 shedding (Fig. 2A) by NL63-S compared to SARS-S.

We next determined if coexpression of SARS-S or NL63-S with ACE2 can also reduce ACE2 expression. One rationale behind this approach is the observation that interactions of viral glycoproteins with their cognate cellular receptors within the secretory pathways of infected cells can lead to formation of receptor-glycoprotein complexes and subsequent receptor degradation (12). In addition, ligation of ACE2 on neighboring cells by surface-expressed S protein could contribute to ACE2 downregulation under these conditions. To investigate if coexpression of SARS-S and NL63-S interferes with ACE2 expression levels, we coexpressed these proteins in 293T cells stably expressing ACE2. Expression of SARS-S but not expression of NL63-S or other SARS-CoV proteins reduced ACE2 levels in transiently transfected 293T cells (Fig. 2E and F), at least under optimal transfection conditions, indicating that expression of SARS-S but not other SARS-CoV proteins in infected cells could interfere with ACE2 expression.

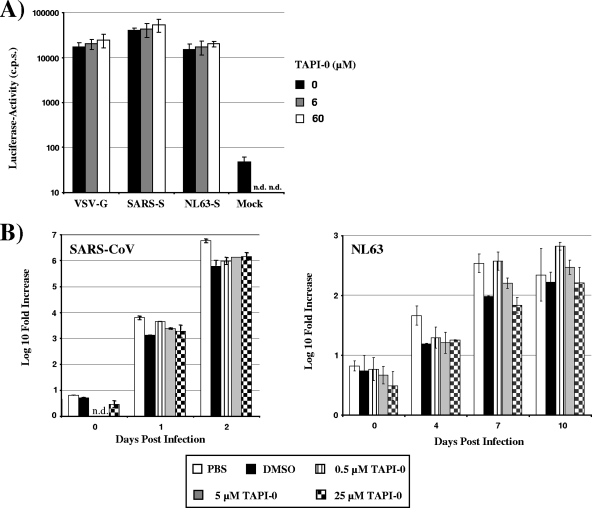

Haga and colleagues suggested that ACE2 shedding upon binding to SARS-S is required for uptake of SARS-CoV particles into 293T cells (8). We therefore assessed if ACE2 shedding is required for productive SARS-CoV and NL63 infection. To this end, we investigated if TAPI-0, which prevented ACE2 shedding in the experimental settings described above (Fig. 2C and D), could inhibit transduction of cells by a lentiviral vector pseudotyped with SARS-S and NL63-S. Preincubation of target cells with TAPI-0 did not inhibit transduction of ACE2-transfected 293T cells by SARS-S- and NL63-S-bearing pseudotypes (Fig. 3A). More importantly, TAPI-0 did not inhibit replication of SARS-CoV and NL63 in Vero E6 cells (Fig. 3B), indicating that S protein-induced ACE2 shedding is dispensable for replication of SARS-CoV and NL63.

FIG. 3.

Shedding of ACE2 is dispensable for SARS-CoV and NL63 spread. (A) In order to determine the importance of TACE activity for SARS-S- and NL63-S-driven infectious entry, ACE2-transfected 293T cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of TAPI-0 and infected with infectivity-normalized lentiviral pseudotypes bearing the indicated glycoproteins. At 72 h postinfection, the cells were lysed and the luciferase activities in cell lysates were determined by employing a commercially available kit. (B) To assess the importance of ACE2 shedding to SARS-CoV and NL63 spread, Vero E6 cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of TAPI-0 or pretreated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a control and then infected with SARS-CoV (Frankfurt strain) or NL63 at an MOI of 0.001. Supernatants of the infected and noninfected cells were taken at the indicated time points postinfection, and the number of viral genome copies was determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). The following primers and probes were used for detection of the SARS-CoV genome: BNITMSARS1 (5′-TTATCACCCGCGAAGAAGCT-3′) (forward primer), BNITMSARAs2 (5′-CTCTAGTTGCATGACAGCCCTC-3′) (reverse primer), BNITMSARP (5′-FAM-TCGTGCGTGGATTGGCTTTGATGT-TAMRA-3′) (probe). For detection of the NL63 genome, the following primers and probes were used: 63RF2 (5′-CTTCTGGTGACGCTAGTACAGCTTAT-3′) (forward primer), 63RR2 (5′-AGACGTCGTTGTAGATCCCTAACAT-3′) (reverse primer), and 63RP (5′-FAM-CAGGTTGCTTAGTGTCCCATCAGATTCAT-3′-TAMRA) (probe). The SARS-CoV and NL63-specific primers both recognize ORF1B sequences. The result of a representative experiment carried out in duplicates is shown.

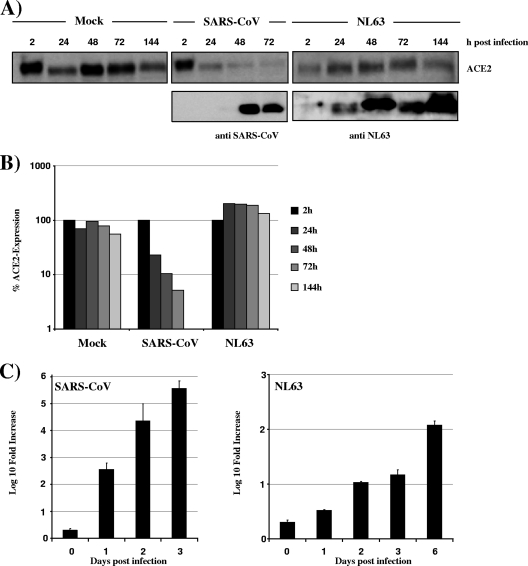

Our results indicated that SARS-S binds to ACE2 with higher efficiency than NL63-S and that this correlates with more efficient ACE2 shedding. We then examined how these findings related to ACE2 expression in SARS-CoV- and NL63-infected cells. Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV (Frankfurt strain) and NL63 at an equal multiplicity of infection (MOI), and ACE2 expression in cell lysates (Fig. 4A and B) and viral copy numbers in the cellular supernatants (Fig. 4C) were analyzed. SARS-CoV replicated with higher efficiency than NL63, with RNA levels in supernatants of SARS-CoV-infected cells at day 1 postinfection being comparable to those in NL63 cultures at 6 days postinfection (Fig. 4C). Replication of SARS-CoV was associated with efficient downregulation of ACE2 expression (Fig. 4A and B), which correlated inversely with viral RNA levels and expression of Nsp8 in cell lysates. In contrast, no appreciable ACE2 downregulation was observed in NL63-infected cell cultures, despite an increase in RNA levels and expression of NL63 proteins (Fig. 4A to C). Thus, SARS-CoV downregulates its receptor, and the S protein might be instrumental to receptor interference. A direct comparison of ACE2 downregulation in SARS-CoV- and NL63-infected cultures was not possible due to the differential replication efficiencies. However, it can be speculated that relatively inefficient ACE2 engagement by NL63 might contribute to the reduced replication and ACE2 downmodulation compared to SARS-CoV.

FIG. 4.

Downmodulation of ACE2 expression in SARS-CoV-infected cells. (A) Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV (Frankfurt strain) or NL63 at an MOI of 0.001 in duplicates. At the indicated times postinfection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lysed with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer, and analyzed for expression of ACE2 or viral proteins by Western blot analysis. For detection of viral proteins, an antibody directed against SARS-CoV Nsp8 and a serum reactive against NL63-infected cells were used. (B) The signals for ACE2 in the cellular lysates shown in panel A were quantified using ImageJ software and are shown relative to the signals measured at 2 h postinfection. (C) The supernatants of the infected cells described above were analyzed for viral genome copies by real-time RT-PCR.

Collectively, our data indicate that SARS-S engages ACE2 more efficiently than NL63-S and that this capacity correlates with more efficient induction of ACE2 shedding. Shedding of soluble ACE2 into the cellular supernatants upon binding of the viral S protein might be mainly responsible for the markedly reduced ACE2 expression in the context of SARS-CoV infection (Fig. 2 and 4) (8, 16), albeit trapping and subsequent degradation of ACE2 in the constitutive secretory pathway of infected cells might contribute (Fig. 2E and F), a possibility that deserves further investigation. Previous studies demonstrated that soluble ACE2 can be released in the supernatants of cells exposed to SARS-S or PMA (8, 18) and that release is facilitated by ADAM10 (PMA) and/or ADAM17/TACE (PMA, SARS-S), which are believed to cleave ACE2 between amino acids 716 and 741 (15). Notably, it was suggested that TACE-dependent ACE2 release is induced by SARS-S but not NL63-S binding to ACE2 and that this process is required for infectious SARS-CoV entry (8). However, the latter conclusion was supported only by virus uptake experiments (8), and it was not determined if uptake indeed resulted in infection. For instance, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is readily taken up by HeLa cells, but uptake does not result in productive infection (21), indicating that measuring uptake might not be appropriate to determine the efficiency of infectious entry. Our results confirm that SARS-S promotes ACE2 shedding, albeit this effect was not exclusive to SARS-S and was also observed with NL63-S. More efficient induction of ACE2 shedding by virion-associated, trimeric NL63-S compared to soluble, dimeric NL63-S (Fig. 2) was not unexpected, since the former binds to ACE2 with higher avidity. Notably, inhibition experiments with TAPI-0, an ADAM17/TACE inhibitor (24) previously shown to abrogate PMA- and SARS-S-induced ACE2 shedding (8, 18), demonstrated that shedding is dispensable for efficient viral spread (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that ACE2 shedding is a mere byproduct of SARS-CoV and NL63 infection and is not required for infectious entry. Whether shedding of ACE2 promotes the release of infectious particles by preventing interactions between SARS-S on progeny virions and cellular ACE2 remains to be determined (since genome copies and not infectivity in cellular supernatants were quantified in Fig. 3B). Anyway, soluble ACE2 might impact viral spread, since binding to soluble receptor has been shown to block SARS-S-dependent infectious entry (10). It also remains to be clarified if S protein-induced ACE2 release promotes lung injury. While soluble ACE2 can be used to combat lung injury (13, 16), the reduction of local concentrations of membrane-associated ACE2 might indeed promote SARS development.

Replication of SARS-CoV in Vero E6 cells was robust and resulted in efficient ACE2 downregulation (Fig. 4). In contrast, NL63 replicated in Vero E6 cells with relatively low efficiency and did not induce ACE2 downregulation, at least under the conditions tested. In conjunction with the results obtained for recombinant S proteins (Fig. 1), these observations suggest that relatively inefficient ACE2 binding of NL63 relative to SARS-CoV could result in both reduced viral replication and ACE2 downregulation. Conversely, acquisition of increased ACE2 binding capacity might cause emergence of pathogenic NL63 variants. Ultimately, these questions can be addressed only by generation of chimeric viruses and their analysis in animal models for SARS. The recent establishment of a reverse genetic system for NL63 (5) and an aged mouse model for SARS pathogenesis (27) will be instrumental to these research endeavors.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. F. Schulz for support and BMBF (01 KI 0705 to F.W.; 01KI 0703 to I.G., S.B., and S.P.) and the Center for Infection Biology (I.S.) at Hannover Medical School for funding. G.S. was supported by grant R01AI074986 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banach, S., J. M. Orenstein, L. M. Fox, S. H. Randell, A. H. Rowley, and S. C. Baker. 2009. Human airway epithelial cell culture to identify new respiratory viruses: coronavirus NL63 as a model. J. Virol. Methods 156:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastien, N., K. Anderson, L. Hart, P. Van Caeseele, K. Brandt, D. Milley, T. Hatchette, E. C. Weiss, and Y. Li. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63 infection in Canada. J. Infect. Dis. 191:503-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu, S. S., K. H. Chan, K. W. Chu, S. W. Kwan, Y. Guan, L. L. Poon, and J. S. Peiris. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63 infection and other coronavirus infections in children hospitalized with acute respiratory disease in Hong Kong, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1721-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding, Y., L. He, Q. Zhang, Z. Huang, X. Che, J. Hou, H. Wang, H. Shen, L. Qiu, Z. Li, J. Geng, J. Cai, H. Han, X. Li, W. Kang, D. Weng, P. Liang, and S. Jiang. 2004. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J. Pathol. 203:622-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson, E. F., B. Yount, A. C. Sims, S. Burkett, R. J. Pickles, and R. S. Baric. 2008. Systematic assembly of a full-length infectious clone of human coronavirus NL63. J. Virol. 82:11948-11957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebihara, T., R. Endo, X. Ma, N. Ishiguro, and H. Kikuta. 2005. Detection of human coronavirus NL63 in young children with bronchiolitis. J. Med. Virol. 75:463-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fouchier, R. A., N. G. Hartwig, T. M. Bestebroer, B. Niemeyer, J. C. de Jong, J. H. Simon, and A. D. Osterhaus. 2004. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:6212-6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haga, S., N. Yamamoto, C. Nakai-Murakami, Y. Osawa, K. Tokunaga, T. Sata, N. Yamamoto, T. Sasazuki, and Y. Ishizaka. 2008. Modulation of TNF-alpha-converting enzyme by the spike protein of SARS-CoV and ACE2 induces TNF-alpha production and facilitates viral entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:7809-7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamming, I., W. Timens, M. L. Bulthuis, A. T. Lely, G. J. Navis, and H. van Goor. 2004. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 203:631-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann, H., M. Geier, A. Marzi, M. Krumbiegel, M. Peipp, G. H. Fey, T. Gramberg, and S. Pöhlmann. 2004. Susceptibility to SARS coronavirus S protein-driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 319:1216-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmann, H., K. Pyrc, L. van der Hoek, M. Geier, B. Berkhout, and S. Pöhlmann. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:7988-7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoxie, J. A., J. D. Alpers, J. L. Rackowski, K. Huebner, B. S. Haggarty, A. J. Cedarbaum, and J. C. Reed. 1986. Alterations in T4 (CD4) protein and mRNA synthesis in cells infected with HIV. Science 234:1123-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai, Y., K. Kuba, S. Rao, Y. Huan, F. Guo, B. Guan, P. Yang, R. Sarao, T. Wada, H. Leong-Poi, M. A. Crackower, A. Fukamizu, C. C. Hui, L. Hein, S. Uhlig, A. S. Slutsky, C. Jiang, and J. M. Penninger. 2005. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 436:112-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwai, M., and M. Horiuchi. 2009. Devil and angel in the renin-angiotensin system: ACE-angiotensin II-AT(1) receptor axis vs. ACE2-angiotensin-(1-7)-Mas receptor axis. Hypertens. Res. 32:533-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia, H. P., D. C. Look, P. Tan, L. Shi, M. Hickey, L. Gakhar, M. C. Chappell, C. Wohlford-Lenane, and P. B. McCray, Jr. 2009. Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 297:L84-L96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuba, K., Y. Imai, S. Rao, H. Gao, F. Guo, B. Guan, Y. Huan, P. Yang, Y. Zhang, W. Deng, L. Bao, B. Zhang, G. Liu, Z. Wang, M. Chappell, Y. Liu, D. Zheng, A. Leibbrandt, T. Wada, A. S. Slutsky, D. Liu, C. Qin, C. Jiang, and J. M. Penninger. 2005. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 11:875-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert, D. W., N. M. Hooper, and A. J. Turner. 2008. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and new insights into the renin-angiotensin system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 75:781-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert, D. W., M. Yarski, F. J. Warner, P. Thornhill, E. T. Parkin, A. I. Smith, N. M. Hooper, and A. J. Turner. 2005. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). J. Biol. Chem. 280:30113-30119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, W., M. J. Moore, N. Vasilieva, J. Sui, S. K. Wong, M. A. Berne, M. Somasundaran, J. L. Sullivan, K. Luzuriaga, T. C. Greenough, H. Choe, and M. Farzan. 2003. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426:450-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, W., J. Sui, I. C. Huang, J. H. Kuhn, S. R. Radoshitzky, W. A. Marasco, H. Choe, and M. Farzan. 2007. The S proteins of human coronavirus NL63 and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus bind overlapping regions of ACE2. Virology 367:367-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maréchal, V., F. Clavel, J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 1998. Cytosolic Gag p24 as an index of productive entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2208-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathewson, A. C., A. Bishop, Y. Yao, F. Kemp, J. Ren, H. Chen, X. Xu, B. Berkhout, L. van der Hoek, and I. M. Jones. 2008. Interaction of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus and NL63 coronavirus spike proteins with angiotensin converting enzyme-2. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2741-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moës, E., L. Vijgen, E. Keyaerts, K. Zlateva, S. Li, P. Maes, K. Pyrc, B. Berkhout, L. van der Hoek, and M. Van Ranst. 2005. A novel pancoronavirus RT-PCR assay: frequent detection of human coronavirus NL63 in children hospitalized with respiratory tract infections in Belgium. BMC Infect. Dis. 5:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohler, K. M., P. R. Sleath, J. N. Fitzner, D. P. Cerretti, M. Alderson, S. S. Kerwar, D. S. Torrance, C. Otten-Evans, T. Greenstreet, K. Weerawarna, et al. 1994. Protection against a lethal dose of endotoxin by an inhibitor of tumour necrosis factor processing. Nature 370:218-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mossel, E. C., J. Wang, S. Jeffers, K. E. Edeen, S. Wang, G. P. Cosgrove, C. J. Funk, R. Manzer, T. A. Miura, L. D. Pearson, K. V. Holmes, and R. J. Mason. 2008. SARS-CoV replicates in primary human alveolar type II cell cultures but not in type I-like cells. Virology 372:127-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie, Y., P. Wang, X. Shi, G. Wang, J. Chen, A. Zheng, W. Wang, Z. Wang, X. Qu, M. Luo, L. Tan, X. Song, X. Yin, J. Chen, M. Ding, and H. Deng. 2004. Highly infectious SARS-CoV pseudotyped virus reveals the cell tropism and its correlation with receptor expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321:994-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts, A., C. Paddock, L. Vogel, E. Butler, S. Zaki, and K. Subbarao. 2005. Aged BALB/c mice as a model for increased severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome in elderly humans. J. Virol. 79:5833-5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sims, A. C., R. S. Baric, B. Yount, S. E. Burkett, P. L. Collins, and R. J. Pickles. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of human ciliated airway epithelia: role of ciliated cells in viral spread in the conducting airways of the lungs. J. Virol. 79:15511-15524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skowronski, D. M., C. Astell, R. C. Brunham, D. E. Low, M. Petric, R. L. Roper, P. J. Talbot, T. Tam, and L. Babiuk. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a year in review. Annu. Rev. Med. 56:357-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To, K. F., and A. W. Lo. 2004. Exploring the pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the tissue distribution of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and its putative receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). J. Pathol. 203:740-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vabret, A., T. Mourez, J. Dina, L. van der Hoek, S. Gouarin, J. Petitjean, J. Brouard, and F. Freymuth. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1225-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Hoek, L. 2007. Human coronaviruses: what do they cause? Antivir. Ther. 12:651-658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Hoek, L., K. Sure, G. Ihorst, A. Stang, K. Pyrc, M. F. Jebbink, G. Petersen, J. Forster, B. Berkhout, and K. Uberla. 2005. Croup is associated with the novel coronavirus NL63. PLoS Med. 2:e240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, P., J. Chen, A. Zheng, Y. Nie, X. Shi, W. Wang, G. Wang, M. Luo, H. Liu, L. Tan, X. Song, Z. Wang, X. Yin, X. Qu, X. Wang, T. Qing, M. Ding, and H. Deng. 2004. Expression cloning of functional receptor used by SARS coronavirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315:439-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]