Abstract

Ebolavirus (EBOV) entry into cells requires proteolytic disassembly of the viral glycoprotein, GP. This proteolytic processing, unusually extensive for an enveloped virus entry protein, is mediated by cysteine cathepsins, a family of endosomal/lysosomal proteases. Previous work has shown that cleavage of GP by cathepsin B (CatB) is specifically required to generate a critical entry intermediate. The functions of this intermediate are not well understood. We used a forward genetic strategy to investigate this CatB-dependent step. Specifically, we generated a replication-competent recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus bearing EBOV GP as its sole entry glycoprotein and used it to select viral mutants resistant to a CatB inhibitor. We obtained mutations at six amino acid positions in GP that independently confer complete resistance. All of the mutations reside at or near the GP1-GP2 intersubunit interface in the membrane-proximal base of the prefusion GP trimer. This region forms a part of the “clamp” that holds the fusion subunit GP2 in its metastable prefusion conformation. Biochemical studies suggest that most of the mutations confer CatB independence not by altering specific cleavage sites in GP but rather by inducing conformational rearrangements in the prefusion GP trimer that dramatically enhance its susceptibility to proteolysis. The remaining mutants did not show the preceding behavior, indicating the existence of multiple mechanisms for acquiring CatB independence during entry. Altogether, our findings suggest that CatB cleavage is required to facilitate the triggering of viral membrane fusion by destabilizing the prefusion conformation of EBOV GP.

Filoviruses are enveloped, filamentous, nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses that can cause a deadly hemorrhagic fever with case fatality rates in excess of 90% (see references 4, 20, and 37 for recent reviews). All known filoviruses belong to one of two genera: Ebolavirus (EBOV), consisting of the five species Zaire (ZEBOV), Côte d'Ivoire, Sudan, Reston, and Bundibugyo (tentative); and Marburgvirus, consisting of the single Lake Victoria species (21, 62).

Cell entry by filoviruses is mediated by their envelope glycoprotein, GP (60, 68). Mature GP is a trimer of three disulfide-linked GP1-GP2 heterodimers. GP1 and GP2 are generated by endoproteolytic cleavage of the GP0 precursor polypeptide by a furin-like protease during transport to the cell surface (31, 39, 63, 69). The membrane-distal subunit, GP1, mediates viral adhesion to host cells (10, 18, 38, 42, 56, 59) and regulates the activity of the transmembrane subunit, GP2, which catalyzes fusion of viral and cellular membrane bilayers (30, 39, 41, 64, 65). The consequence of membrane fusion is cytoplasmic delivery of the viral nucleocapsid cargo.

Lee et al. (39) recently solved the crystal structure of a ZEBOV GP prefusion trimer lacking the heavily glycosylated GP1 mucin domain (Muc) and the GP2 transmembrane domain (see Fig. 5). The three GP1 subunits together form a bowl-like structure encircled by sequences from the three GP2 subunits. The trimer is held together by GP1-GP2 and GP2-GP2 contacts; the hydrophobic GP2 fusion loop packs against the external surface of adjacent GP1 subunits, and each GP2 subunit contributes a strand to a trimeric α-helical coiled-coil stem. GP1 is organized into three subdomains. The base is intimately associated with GP2 and clamps it in its prefusion conformation. The head is proposed to mediate virus receptor binding during entry (10, 18, 38, 42). The glycan cap resides at the top of the trimer and is critical for GP assembly but must be removed during entry (see below) (31, 42). The base and glycan cap are connected by the β13-β14 loop, which was not visualized in the structure. The location and structure of the Muc domain are also unknown, but it is proposed to sheathe the top and/or sides of the prefusion GP trimer (39). Muc is dispensable for ZEBOV GP-dependent entry in tissue culture but may play roles in virus-cell adhesion and immune evasion in vivo (31, 42, 44, 56, 59).

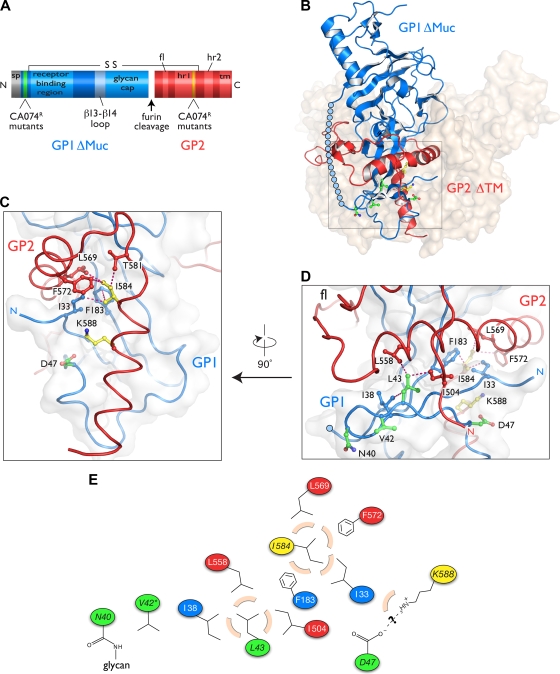

FIG. 5.

CA074R mutations localize at or near the GP1-GP2 interface in the GP prefusion crystal structure. In all diagrams, GP1 is depicted in blue, GP2 in red, GP1 CA074R mutations in green, and GP2 CA074R mutations in yellow. (A) Linear representation of the amino acid sequence of GPΔMuc. S-S indicates the intersubunit disulfide bond between C53 and C609. sp, signal peptide; fl, fusion loop; hr1 and hr2, heptad repeats; tm, transmembrane domain; N, N terminus; C, C terminus. (B) Structure of GP in a prefusion conformation (39). Cartoon representation of a GP1-GP2 monomer is shown. Remaining subunits are shown as a surface-shaded watermark. The boxed inset contains the membrane-proximal base of the trimer, in which the CA074R mutations are located. The β13-β14 loop is modeled as a chain of blue circles. (C) Magnified view of the inset shown in panel B rotated by 90°. The side chains of D47, I584, K588, and their contacting residues are shown. Dashed pink lines connect atoms from different side chains separated by ≤3.9 Å. Other CA074R residues are not shown for clarity. (D) View shown in panel C rotated by 90°. (E) Schematic diagram of the potential interactions made by residues mutated in the CA074R viruses. Residues approaching ≤3.9 Å to each CA074R residue are shown. Beige arcs, hydrophobic interactions; dashed lines, potential ionic interactions. Visualizations of the GP structures shown in panels B to D (Protein Data Bank accession no. 3CSY) were rendered in Pymol (Delano Scientific).

Crystal structures of ZEBOV GP2 in its postfusion conformation indicate that filovirus GP is a “class I” viral membrane fusion protein (41, 65). Like the prototypic class I fusion proteins of human immunodeficiency virus and influenza virus, GP2 contains a hydrophobic fusion peptide near its N terminus and N- and C-terminal α-helical heptad repeat sequences (HR1 and HR2, respectively) (22, 28, 30, 39, 41, 64, 65, 67) (see Fig. 5). GP2 drives membrane fusion by undergoing large-scale conformational changes; the prefusion HR1 helix-loop-helix rearranges to an unbroken α-helix, projecting the fusion loop into the endosomal membrane, and GP2 jackknifes on itself to form a hairpin-like structure in which the HR2s pack against grooves in the trimeric HR1 coiled coil (41, 65).

The available GP structures make clear that the transition of GP2 from prefusion to postfusion conformation requires its release from its binding groove in the GP1 base subdomain. For all known class I fusion proteins, this transition is controlled by priming and triggering events. Priming typically involves a single endoproteolytic cleavage of the glycoprotein mediated by a cellular protease within the secretory pathway of the virus-producer cells (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus ENV → SU + TM by furin [27]). This cleavage is essential because it liberates an N-terminal fusion peptide and allows the glycoprotein to rearrange during fusion. Unusually for a class I fusion glycoprotein, however, ZEBOV GP does not require cleavage to GP1 and GP2 by a furin-like protease, even though this cleavage occurs efficiently (46, 69). Instead, the GP trimer is primed by extensive proteolytic remodeling during entry. This process is mediated by cysteine cathepsins, a class of papain superfamily cysteine proteases active within the cellular endosomal/lysosomal pathway (14, 54).

The cysteine cathepsins B (CatB) and L (CatL) play essential and accessory roles, respectively, in ZEBOV entry into Vero cells (14). The functions of these enzymes in viral entry can be recapitulated in vitro. Incubation of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudotypes bearing ZEBOV GP (VSV-GP) with a mixture of purified human CatL and CatB, or with the bacterial protease thermolysin (THL), results in the cleavage and removal of GP1 Muc and glycan cap sequences, leaving a stable ∼17-kDa N-terminal GP1 fragment and intact GP2 (see Fig. 5) (18, 54). VSV particles containing this GP17K intermediate no longer require CatB activity within cells, strongly suggesting that this protease plays a critical role in generating a related primed species during viral entry (54). Strikingly, incubation of VSV-GP with CatL alone (14, 54) or with bovine chymotrypsin (CHT) (this study) (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 7) generates a similar but distinct GP18K intermediate (containing a slightly larger ∼18-kDa GP1 fragment) that cannot bypass the requirement for CatB during entry. Therefore, the removal of a few residues from GP18K by CatB is crucial for viral entry. The reason for this requirement is unknown. Finally, VSV-GP17K particles cannot infect cells completely devoid of cysteine cathepsin activity, indicating the existence of at least one additional cysteine protease-dependent step during entry (34, 54; present study). The signal that acts on a fully primed GP intermediate to trigger membrane fusion remains unknown.

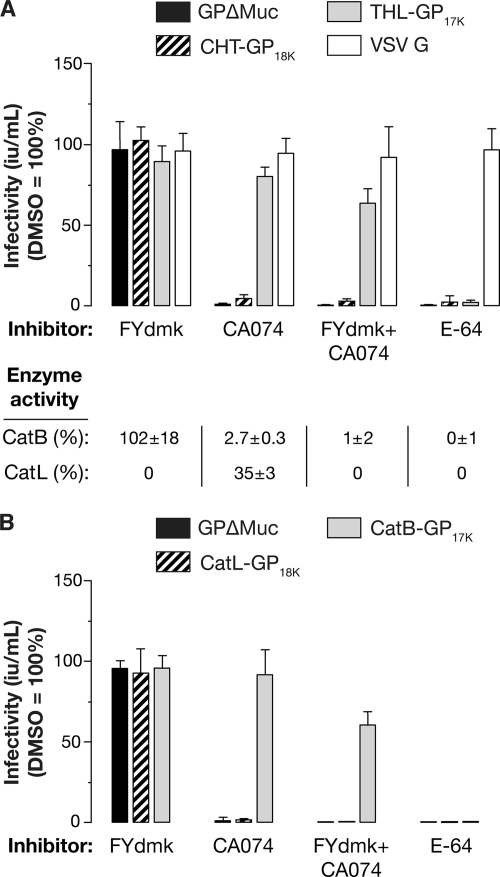

FIG. 1.

CatB activity is required for entry of ZEBOV GP-dependent entry, whereas CatL activity is dispensable. Vero cells were pretreated for 4 h with 1% (vol/vol) DMSO (vehicle), 0.5 μM FYdmk (CatL-selective inhibitor), 80 μM CA074 (CatB-selective inhibitor), 0.5 μM FYdmk plus 80 μM CA074, or 300 μM E64 (pan-cysteine cathepsin inhibitor). (A) The cells were then challenged with VSV-GPΔMuc, CHT-derived VSV-GP18K (CHT-GP18K), THL-derived VSV-GP17K (THL-GP17K), or VSV-G pseudotypes at a low MOI (0.02 to 0.1 eGFP-positive infectious units [iu] per cell) in the presence of drug, and viral titers (iu/ml) were determined at 18 h postinfection. CatB and CatL activities in extracts prepared from a parallel set of pretreated cells were measured by fluorogenic peptide turnover and are shown (bottom). Averages ± standard deviations (SD) for six trials from three independent experiments are shown. CatL activity below the detection threshold is indicated as zero without an accompanying SD. (B) Vero cells pretreated with protease inhibitors were challenged with VSV-GPΔMuc, cathepsin L-derived VSV-GP18K (CatL-GP18K), or cathepsin B-derived VSV-GP17K (CatB-GP17K), and viral infectivity was measured as described above. Averages ± SD for three trials from a representative experiment are shown.

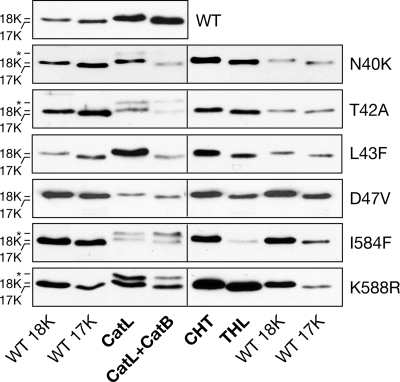

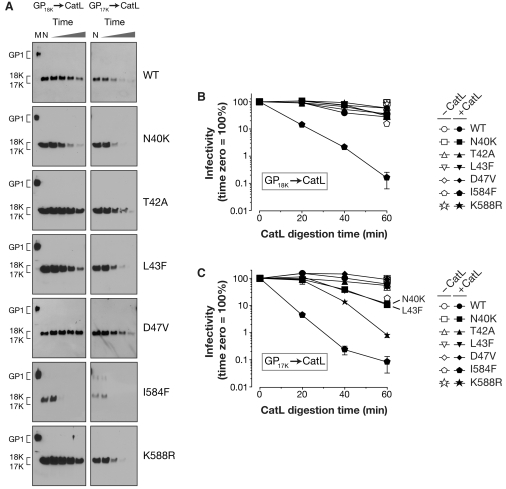

FIG. 7.

rVSV-GPΔMuc mutants resemble the WT in cleavage to GP18K and GP17K intermediates. WT or mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc was incubated with the indicated protease(s) as described in Materials and Methods and then deglycosylated with PNGaseF (except for N40K and T42A, which lack the N40 glycan and do not require deglycosylation at this position). The resulting GP1 proteolytic fragments were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting. Shorter protease incubation times were necessary to obtain cleavage intermediates for some mutants (see text for details). Positions of uncleaved GP1 and the ∼18-kDa and ∼17-kDa cleavage fragments are indicated on the left. *, partially cleaved GP fragment of unknown composition. Experimental samples shown on each gel (bold labels) were flanked by WT samples cleaved with CHT (WT 18K) or THL (WT 17K) to provide markers of band mobility.

In this study, we used a forward genetic strategy to investigate the CatB-dependent step in ZEBOV entry. Specifically, we engineered and rescued a recombinant VSV (rVSV) encoding a mucin domain-deleted ZEBOV GP in place of the VSV glycoprotein G and used it to select viral mutants resistant to the CatB inhibitor CA074. Analysis of these viruses identified mutations in both GP1 and GP2 that allow CatB-independent cell entry. We found that GP18K and/or GP17K intermediates derived from some but not all of the mutant GPs are conformationally distinct from the wild type (WT), suggesting the existence of multiple mechanisms for CA074 resistance. Taken together, our results indicate that ZEBOV GP→GP17K cleavage by CatB promotes fusion triggering and viral entry by destabilizing the prefusion conformation of GP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero and 293T cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio-Products). An rVSV expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and ZEBOV GP lacking the mucin domain (Δ309-489; ΔMuc) (31) was generated by insertion of the eGFP-coding region flanked by the conserved VSV gene start and end sequences between the leader and N gene and by replacement of the VSV G-coding region with that of ZEBOV GPΔMuc. The amino acid sequence of ZEBOV GPΔMuc is identical to that of the Mayinga field isolate (GenBank accession number AF086833), except that it lacks Muc and contains the mutation I662V within the GP2 membrane-spanning domain. This virus (rVSV-GPΔMuc) resembles an rVSV encoding GP that was described previously and is a candidate live-attenuated ZEBOV vaccine (23, 32). A second rVSV encoding an mRFP-P fusion protein (in place of P) and VSV G in its normal position (rVSV-G) was used as a control virus, as shown in Fig. 2; see also Fig. 6. Its construction and rescue is to be described elsewhere (D. K. Cureton and S. P. Whelan, unpublished data).

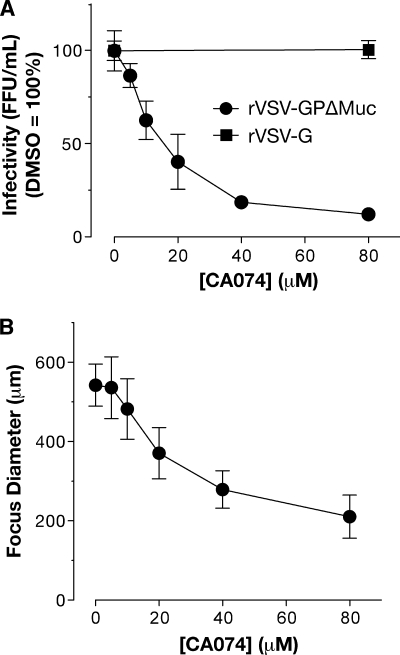

FIG. 2.

CatB activity is required for entry and spread of rVSV-GPΔMuc. Vero cells were pretreated with different concentrations of CA074 for 4 h and then challenged with serial dilutions of rVSV-GPΔMuc or rVSV-G for 1.5 h. After removing the viral inoculum, the cells were overlaid with agarose containing CA074 at a concentration equal to that used during pretreatment. (A) Viral titers (FFU/ml) were determined at 16 hpi. Averages ± standard deviations (SD) are shown for four trials from two independent experiments. (B) Diameters (averages ± SD) of 10 to 30 fluorescent foci were measured from images captured at 16 hpi.

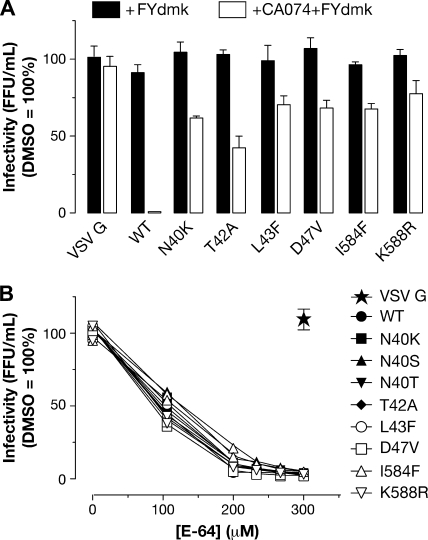

FIG. 6.

CatB and CatL are dispensable for mutant GPΔMuc-mediated entry, but cysteine cathepsin activity is still required. (A) Vero cells were pretreated for 4 h with 1% DMSO, 0.5 μM FYdmk, or 0.5 μM FYdmk plus 80 μM CA074. The cells were then incubated for 1.5 h with the WT, CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc, or rVSV-G at an MOI of 0.001 FFU/cell and overlaid with agarose containing DMSO or drug. Viral titers (FFU/ml) were determined at 18 hpi. Averages ± standard deviations for three trials are shown. (B) Vero cells were pretreated for 4 h with various concentrations of E-64, then challenged with the WT, CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc, or rVSV-G, and overlaid with agarose containing no drug. Average viral titers for two trials from a representative experiment are shown.

rVSV-GPΔMuc was rescued from cDNA as described previously (66). Doubly plaque-purified rVSV-GPΔMuc clones were amplified in Vero cells, concentrated by pelleting through 10% sucrose cushions prepared in NT (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 135 mM NaCl), resuspended in NT, and stored at −80°C. These concentrated virus preparations routinely contained infectious titers of ∼1 × 1010 focus-forming units (FFU) per ml. Sequencing of cDNA corresponding to the GPΔMuc-coding region within the genomes of these viral particles confirmed that no nucleotide changes had occurred during virus recovery and amplification. All experiments with rVSV-GPΔMuc were carried out using enhanced biosafety level 2 procedures approved by the Einstein Institutional Biosafety Committee. VSV pseudotypes expressing eGFP and bearing VSV G (VSV-G) or ZEBOV GPΔMuc (VSV-GPΔMuc) were generated as described previously (14).

Protease inhibitor treatments.

Cysteine protease inhibitors FYdmk (Z-Phe-Tyr-(tert-butyl)-diazomethylketone; EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ), CA074 [N-(L-3-trans-propylcarbamoyloxirane-2-carbonyl)-Ile-Pro-OH], and E-64 [L-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucyl-amide-(4-guanido)-butane] (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and dispensed into culture medium immediately before use. To inhibit protease activity in cells, monolayers were incubated with drug-containing media at 37°C for 4 h prior to virus infection.

Measurements of cellular cysteine cathepsin activity.

To measure the effects of protease inhibitor treatment on intracellular CatB and CatL activities (Fig. 1), intact Vero cells were pretreated with protease inhibitors for 4 h and then washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline to remove residual extracellular inhibitors prior to lysis. Cells were then lysed in MES buffer [50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (pH 5.5), 135 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA] containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 to 60 min at 4°C, and lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 6,000 × g. The enzymatic activities of CatB and CatL in the acidified postnuclear extracts were assayed with fluorogenic peptide substrates Z-Arg-Arg-AMC (Bachem Inc., Torrance, CA) and (Z-Phe-Arg)2-R110 (Invitrogen), respectively, as described previously (19). To enhance assay specificity, extracts were pretreated with 0.5 μM FYdmk or 1 μM CA074 for 20 min at room temperature immediately prior to measuring the activities of CatB or CatL, respectively. These FYdmk and CA074 concentrations inactivate CatL and CatB in vitro (data not shown), preventing promiscuous turnover of the CatB substrate by CatL and vice versa. As an additional control for assay specificity, enzyme activities were assessed in extracts pretreated with both 0.5 μM FYdmk and 1 μM CA074. This experiment demonstrated that, as expected, CatB substrate turnover was CA074 sensitive and CatL substrate turnover was FYdmk sensitive.

Viral infectivity measurements.

Infectivities of VSV pseudotypes were measured by automated counting of eGFP-positive cells using fluorescence microscopy and the CellProfiler software package (11). rVSV-GPΔMuc infectivity was measured by fluorescent-focus assay (FFA). Briefly, Vero cell monolayers were incubated with virus in DMEM containing 2% FBS for 1 to 1.5 h at 37°C, unbound virus was removed, and the cells were overlaid with MEM containing 10% FBS and 0.5% SeaPlaque agarose (Lonza Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). Where indicated, cysteine protease inhibitors were added to the assay overlay medium at the same concentration used to treat cells prior to viral infection. Infection was allowed to proceed at 37°C and eGFP-positive infectious FFU were manually counted by fluorescence microscopy at 12 to 18 h postinfection (hpi). FFU diameters shown in Fig. 2 and 3 were measured from images of microscope fields by using the Axiovision software package (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY).

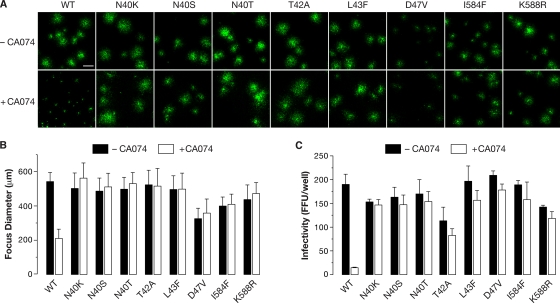

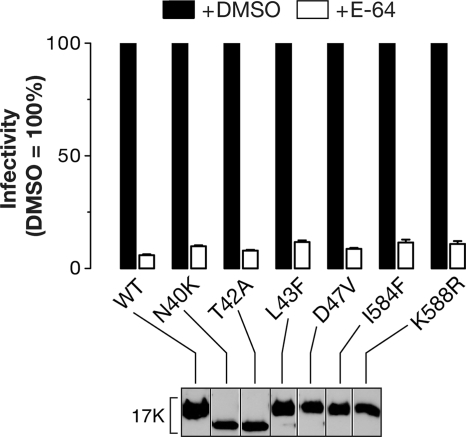

FIG. 3.

Single amino acid mutations at six positions in GPΔMuc enable CatB-independent cell entry. Vero cells were pretreated with 1% DMSO or 80 μM CA074 for 4 h, challenged with WT or CA074-resistant (CA074R) mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc at an MOI of 0.001 FFU/cell for 1.5 h, and then overlaid with agarose containing DMSO (−CA074) or CA074. (A) Images of the fluorescent infection foci were captured at 16 hpi. Results from a single representative experiment are shown. Scale bar in top-left panel, 500 μM. (B) Diameters of these foci were measured. Averages ± standard deviations (SD) for 10 to 30 foci are shown. (C) Viral titers (FFU/well) were determined by FFA. Averages ± SD for three to six trials from a single representative experiment are shown.

Isolation of CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc clones.

CA074-resistant (CA074R) rVSV-GPΔMuc mutant clones were selected by serial passage in Vero cells and isolated by plaque purification. Cell monolayers in six-well plates were incubated with 80 μM CA074 for 4 h to inactivate CatB. Two different plaque isolates of WT rVSV-GPΔMuc were used to infect six wells, each at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 FFU/cell. Virus-containing supernatants were harvested and titrated by FFA at 16 hpi and then used to infect new CA074-treated monolayers. Substantial resistance to CA074 was evident after two serial passages. Mutant clones were doubly plaque-purified under CA074 selection, and the clonal isolates were amplified and concentrated, as described above, in the presence of CA074. All subsequent experiments were performed with these mutant isolates.

To identify mutations in GP conferring CA074 resistance, the sequence of the GPΔMuc-coding region was determined for three clones from each of the 12 independent selections. Viral genomic RNA, extracted from concentrated virus preparations with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR using Superscript II RT (Invitrogen) and Pfu Turbo (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The entire GPΔMuc coding region was amplified by PCR and sequenced. To ensure accuracy and verify clonality, two independent viral preparations were sequenced for each isolate.

Protease digestion reactions.

Concentrated rVSV-GPΔMuc preparations (0.5 to 2 μl) were incubated with CHT (100 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), thermolysin (THL; 200 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), CatL (5 μg/ml; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or CatL (5 μg/ml) plus CatB (20 μg/ml; Athens Research, Athens, GA) at 37°C for the indicated times. CHT and THL reactions were performed in NT buffer and terminated by incubation on ice and addition of phenylmethylsulfonic acid (1 mM) and phosphoramidon (0.5 mM), respectively. CatL and CatB reactions were performed in MES buffer (pH 5.5) and terminated by incubation on ice and addition of E-64 (10 to 50 μM).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Protein samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels as described previously (47). Where indicated, prior to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), acid pH protease digestion reactions were neutralized by the addition of equal volumes of HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and deglycosylated by treatment with protein N-glycosidase F (PNGase F; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To detect GP1, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against GP1 residues 83 to 97 (1:10,000 dilution; a gift from James M. Cunningham, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA), a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:3,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare). Bands were visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

RESULTS

CatB, but not CatL, is required for ZEBOV GPΔMuc-dependent entry into Vero cells.

We showed previously that in Vero cells, the endosomal/lysosomal cysteine proteases cathepsin B (CatB) and cathepsin L (CatL) play essential and accessory roles, respectively, in the entry of VSV pseudotypes bearing VSV-GP or VSV-GPΔMuc and of authentic ZEBOV (14). Other groups have confirmed the importance of CatB, but they have shown, contrary to our initial findings, that CatL is essential for viral entry (34, 54).

To clarify the roles of CatB and CatL in viral entry, we examined the capacity of cysteine cathepsin inhibitors to block infection of Vero cells by VSV-GPΔMuc pseudotypes bearing uncleaved GPΔMuc or cleaved GP18K and GP17K intermediates (the last two generated by incubation of VSV-GPΔMuc with CHT and THL, respectively [Fig. 1A] or CatL and CatL plus CatB, respectively [Fig. 1B]). Cellular extracts were assayed for CatB and CatL activities in parallel to confirm appropriate enzyme inhibition following drug treatment. Complete and selective inhibition of CatL activity with FYdmk treatment had little effect on infection of any of the viruses, demonstrating that CatL is dispensable for entry. Under conditions of very low CatB and moderate CatL activities imposed by CA074 treatment, infection by both VSV-GPΔMuc and VSV-GP18K was greatly reduced, confirming that CatB is critical for entry and that the GP18K intermediate cannot bypass the CatB requirement. In contrast and as shown previously (54), CA074 treatment had little effect on infection by VSV-GP17K, indicating that the cleavage of GPΔMuc to GP17K essentially overcomes the block imposed by this inhibitor. Importantly, pretreatment of cells with FYdmk and CA074 to inactivate both CatL and CatB did little to alter the preceding results obtained with CA074 alone, showing that CatL is dispensable for viral entry, even in the absence of CatB activity. Finally, inactivation of all cysteine cathepsin activities with E-64 substantially inhibited infection by VSV-GP17K, strongly suggesting that (i) there is at least one additional cysteine protease-dependent step in entry and (ii) one or more cysteine protease activities distinct from CatB and CatL are sufficient for viral entry mediated by the GP17K proteolytic intermediate.

Development of a forward genetic strategy to identify CatB-independent variants of ZEBOV GP.

The utility of pseudotypes for studies of EBOV GP-dependent viral entry is undisputed. However, they cannot be used to select GP proteins with altered phenotypes because the GP gene is not encoded in the viral genome and is therefore not heritable by the viral progeny. To overcome this limitation and harness the power of forward genetics in a biosafety level 2 setting, we engineered and rescued an rVSV that expresses a mucin-deleted ZEBOV GP (GPΔMuc) as its sole surface glycoprotein and eGFP as a marker of infected cells. This rVSV-GPΔMuc virus resembles an rVSV bearing full-length ZEBOV GP (but not eGFP) that has been described previously and used to select antibody neutralization escape mutants (23, 58).

To determine whether rVSV-GPΔMuc is suitable for genetic studies of CatB's role in cell entry, we investigated the CatB dependence of this virus. Vero cells were pretreated with CA074 or with vehicle alone and then challenged with rVSV-GPΔMuc. We observed CA074 dose-dependent reductions in both the number of FFU (Fig. 2A) and their diameter (Fig. 2B) (to <10% and ∼50%, respectively, at 80 μM CA074 relative to a control infection), confirming that rVSV-GPΔMuc particles resemble VSV-GPΔMuc pseudotypes in requiring CatB activity to infect Vero cells. Importantly, no reductions in viral titer were obtained in parallel experiments with a control virus (rVSV-G) expressing the endogenous glycoprotein, G (Fig. 2A). This finding indicates that CA074 has little or no effect on VSV gene expression, genome replication, and particle assembly and reinforces the conclusion that this drug acts to specifically block the ZEBOV GP-dependent entry process.

Isolation and sequence analysis of CA074-resistant mutant viruses.

We selected CatB-independent rVSV-GPΔMuc mutants by serial passage of virus in the presence of CA074 (80 μM). Nearly complete resistance to this inhibitor was apparent after two passages, as indicated by the similar viral titers obtained in the absence and presence of CA074 (data not shown, but see Fig. 3). To isolate CA074-resistant viral clones, viruses were plaque purified from supernatants and amplified under CA074 selection. A GPΔMuc-containing genome fragment was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR from 36 CA074-resistant clones, and the resulting cDNA products were sequenced (Table 1). Comparison with the sequence of the parental rVSV-GPΔMuc isolate revealed that each mutant clone encoded at least one amino acid substitution within the GPΔMuc open reading frame. Coding mutations were observed at 10 positions, at least 6 of which independently confer viral resistance to CA074 when changed: residues N40, T42, L43, and D47 in GP1 and I584 and K588 in GP2 (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Single mutants bearing substitutions at each of these six positions were obtained, and all multiple mutants contained a substitution at one of these positions. Subsequent studies were performed with the single mutant CA074-resistant (CA074R) rVSV-GPΔMuc isolates.

TABLE 1.

Mutations in ZEBOV GPΔMuc that confer resistance to CatB inhibitor CA074

| Amino acid change in EBOV GPΔMuc | Corresponding codon changea | No. of clonesb |

|---|---|---|

| N40H | AAT to CAT | 2 |

| N40K | AAT to AAG | 3 |

| N40S | AAT to AGT | 7 |

| N40T | AAT to ACT | 2 |

| N40Y | AAT to TAT | 1 |

| T42A | ACA to GCA | 1 |

| L43F | TTA to TTC | 1 |

| D47V | GAT to GTT | 1 |

| I584F | ATC to TTC | 1 |

| K588R | AAG to AGG | 10 |

Nucleotide changes are underlined and in bold.

Number of viral isolates from independent selections bearing this amino acid change.

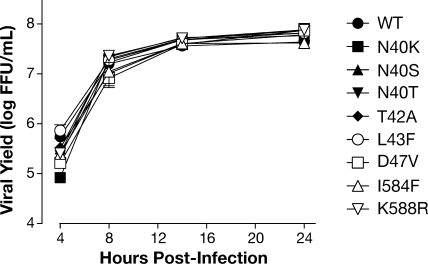

FIG. 4.

WT and CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc viruses grow equally well in Vero cells. WT or CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc were adsorbed to confluent monolayers of Vero cells at an MOI of 3 FFU/cell at 4°C. Following removal of the viral inoculum, the cells were washed with culture medium and shifted to 37°C. At the indicated times, an aliquot was taken from the supernatant, and viral titers were determined by FFA. Averages ± standard deviations for four trials from a representative experiment are shown.

Growth properties of mutant viruses in the presence and absence of CA074.

To compare the WT and mutant clones' requirement for CatB during entry, we pretreated Vero cells with CA074 or with vehicle alone, challenged them with virus, and measured viral infectivity and spread by FFA (Fig. 3). CA074 treatment inhibited infection by WT rVSV-GPΔMuc, as expected, but had little or no effect on cell entry and infection by any of the mutants, as judged by viral titer (Fig. 3C) and FFU diameter measurements (Fig. 3A and B). These results demonstrate that a single amino acid change at any of the six positions in ZEBOV GPΔMuc allows the CA074R viruses to enter Vero cells that contain little or no active CatB.

To rule out complications in interpreting these data arising from differences in viral replication and budding, single-cycle growth curves were generated for WT and CA074R rVSV-GPΔMuc. Similar growth kinetics and viral yields were observed at 24 hpi for all viruses tested, showing that the CA074R mutants do not have a substantial growth advantage or defect relative to WT virus (Fig. 4).

Locations of CA074R mutations in the prefusion GP structure.

We examined the locations of the six residues mutated in the CA074R viruses within the prefusion GP crystal structure (39). Four of these residues are near the N terminus of GP1, and the other two are in the N-terminal heptad repeat region ( ) of GP2 (Table 1 and Fig. 5A). All six residues are located at the base of the prefusion GP trimer, a region in which GP1 is intimately associated with GP2 and clamps it in its prefusion conformation (Fig. 5B) (39). Residues L43 in GP1 and I584 and K588 in GP2 are at the GP1-GP2 intersubunit interface and participate in a web of hydrophobic interactions between GP1 and GP2 (Fig. 5C to E). The side chains of residues D47 in GP1 and K588 in GP2 also closely approach each other. Residues N40 and T42 in GP1 do not appear to interact with GP2. Instead, they are part of an NXT motif for N-linked glycosylation. The inference that the N-linked glycan at residue 40, rather than the side chain itself, determines CatB dependence is supported not only by the T42A mutation but also by our finding that a wide range of amino acid substitutions at N40 confer CA074 resistance (Table 1).

) of GP2 (Table 1 and Fig. 5A). All six residues are located at the base of the prefusion GP trimer, a region in which GP1 is intimately associated with GP2 and clamps it in its prefusion conformation (Fig. 5B) (39). Residues L43 in GP1 and I584 and K588 in GP2 are at the GP1-GP2 intersubunit interface and participate in a web of hydrophobic interactions between GP1 and GP2 (Fig. 5C to E). The side chains of residues D47 in GP1 and K588 in GP2 also closely approach each other. Residues N40 and T42 in GP1 do not appear to interact with GP2. Instead, they are part of an NXT motif for N-linked glycosylation. The inference that the N-linked glycan at residue 40, rather than the side chain itself, determines CatB dependence is supported not only by the T42A mutation but also by our finding that a wide range of amino acid substitutions at N40 confer CA074 resistance (Table 1).

CatB and CatL activities are dispensable for CA074R virus entry, but cysteine cathepsin activity is not.

We examined the capacity of cysteine cathepsin inhibitors to block infection of Vero cells by the WT or mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc (Fig. 6A). A CatL-selective concentration of FYdmk had little effect on infection by either WT or mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc viruses, as previously seen with VSV pseudotypes bearing WT GP or GPΔMuc (Fig. 1) (14), demonstrating that CatL is dispensable in both cases for entry into Vero cells. Interestingly, FYdmk-plus-CA074 treatment to selectively inhibit both CatL and CatB reduced WT infectivity to a much greater extent than did treatment with either drug alone (to ∼0.01% for FYdmk plus CA074 versus ∼90% for FYdmk and ∼5% for CA074) (Fig. 1 and 6 and data not shown), confirming our previous finding that CatL makes a small but measurable contribution to ZEBOV GP-dependent entry in Vero cells, which is revealed when little or no active CatB is present (14). In contrast, FYdmk-plus-CA074 treatment reduced infection by mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc only modestly (to ≥40% for FYdmk plus CA074 versus ≥90% for FYdmk and ≥90% for CA074) (Fig. 1 and 6). Thus, CatB and CatL appear to play redundant but largely dispensable roles in mutant GP-mediated entry.

We next used the pan-cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E-64 to examine the possibility that the CA074R GP mutants no longer require cysteine cathepsin activity during entry. We observed a similar dose-dependent loss of infectivity with both WT and mutant viruses in response to E-64 pretreatment (<5% at 300 μM E-64, relative to a control infection) (Fig. 6B). Thus, despite overcoming the specific requirement for CatB, the GP mutants still require cysteine cathepsins for entry. Moreover, the E-64 and FYdmk-plus-CA074 experiments taken together indicate that cysteine cathepsins other than CatB and CatL can carry out all of the cysteine protease-dependent steps in entry by the CA074R viruses.

CA074R GPs resemble WT GP in proteolytic processing to GP18K and GP17K intermediates.

The cysteine cathepsin dependence of mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc-mediated entry suggests that the CA074R GPs undergo proteolytic cleavage within the host cell endosomal pathway. We thus investigated whether differences in the proteolytic processing of the WT and that of mutant GPs account for the CatB independence of the CA074R viruses. We first asked if a non-CatB cysteine cathepsin (CatL) can substitute for CatB in cleaving the CA074R GPs to a GP17K-like intermediate. We reasoned that although CatL is dispensable for entry, it may be able to carry out the GP→GP17K step redundantly with other non-CatB cysteine cathepsins. Accordingly, the WT and mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc were incubated with CatL alone or with CatL followed by CatB, and the resulting GP1 digestion products were deglycosylated by protein N-glycosidase F treatment and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 7). To facilitate comparison of band mobilities, GP18K and GP17K species derived from WT rVSV-GPΔMuc were loaded alongside the experimental samples. We found that all of the mutants have a cleavage profile similar to that of the WT; CatL and CatL-plus-CatB digestion at pH 5.5 generated GP1 products that comigrated with 18-kDa and 17-kDa GP1 species, respectively, derived from WT GPΔMuc. Similar results were obtained upon incubation of mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc with CHT and THL, respectively, at pH 7.5. This experiment shows that in vitro cleavage of the CA074R GPs by CatL alone is not capable of producing a GP17K-like species and strongly suggests that the mutant viruses cannot use CatL as a substitute for CatB to generate this species during entry. These findings also suggest that the CA074R GPs can be cleaved to GP17K by a specific non-B, non-L cysteine cathepsin active in Vero cells or else bypass this intermediate completely through an unclear mechanism.

Some CA074R GPs are highly susceptible to cleavage to sub-GP17K species.

While carrying out the preceding experiment, we noticed that relatively brief incubations of some rVSV-GPΔMuc mutants, but not the WT, with proteases caused the complete conversion of GP1 to sub-17-kDa fragments or peptides not detected by the anti-GP1 antiserum. This finding raised the possibility that cleaved intermediates derived from these CA074R GPs are conformationally distinct from their WT counterparts. To test this hypothesis, we incubated WT and mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc with CHT or THL to generate GP18K or GP17K intermediates, respectively, inactivated the proteases, and then subjected the intermediates to a second round of proteolysis with CatL. The kinetics of GP1 proteolysis by CatL was monitored at different times postincubation by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 8A). We chose CatL as a probe of GP18K/GP17K conformation in this experiment because it has a broad substrate specificity but cannot itself convert GP18K to GP17K. We observed three distinct phenotypes among the viruses: persistence of both 18-kDa and 17-kDa GP1 fragments through the entire CatL time course (WT, T42A, and D47V), persistence of the 18-kDa fragment but loss of the 17-kDa fragment (N40K, L43F, and K588R), and loss of both 18-kDa and 17-kDa fragments to CatL digestion (I584F). In all cases (including the WT), the 17-kDa GP1 species was more sensitive to proteolysis than its 18-kDa counterpart, suggesting that the cleavage of GP18K to GP17K by CatB renders the glycoprotein more susceptible to proteolysis. Similar results were obtained with prolonged CHT or THL digestion alone (data not shown), indicating that the differences in GP stability are intrinsic to the glycoprotein and determined largely by its cleavage status (i.e., GP18K versus GP17K) rather than the incubation pH (7.5 versus 5.5) or the protease employed. Because the L43F, I584F, and K588R mutations that enhance GP protease susceptibility are buried within the prefusion structure and unlikely to directly alter protease cleavage sites, we infer that these three GP mutants, at least, generate GP18K and/or GP17K intermediates that differ from the WT in the flexibility and accessibility of their polypeptide backbone.

FIG. 8.

GP18K and/or GP17K intermediates of some CA074R GPs are more susceptible to proteolytic inactivation than their WT counterparts. (A) The WT or mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc was incubated with CHT or THL to generate mutant GP18K or GP17K intermediates, respectively. Cleaved intermediates were then incubated with CatL for increasing lengths of time. These samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, and GP1 was detected by Western blotting. In all gels, the lanes from left to right are as follows: M, uncleaved samples from mock protease incubation (left gels only); N, samples initially containing GP18K or GP17K that were incubated for 1 h in acid pH buffer without CatL; and samples initially containing GP18K or GP17K that were incubated with CatL for 0, 20, 40, or 60 min. Positions of uncleaved GP1 and the ∼18-kDa and ∼17-kDa cleavage fragments are indicated on the left. (B and C) Viral titers (FFU/ml) in aliquots from the GP18K (panel B) and GP17K (panel C) proteolysis time courses depicted in panel A were determined and normalized to the 0-h sample. Open symbols represent samples incubated with acid pH buffer alone for 1 h (lane N in gels shown in panel A), and closed symbols represent those incubated with CatL. Averages ± standard deviations for three trials from a representative experiment are shown.

Cleavage of CA074R GPs to sub-GP17K species is associated with viral inactivation.

In a parallel experiment, we examined the consequences of GP1 cleavage to sub-17-kDa species for viral infectivity (Fig. 8B and C). The initial titers of GP18K/GP17K intermediates derived from the WT and CA074R viruses were similar, showing that the mutant intermediates, like their WT counterparts, retain full infectivity (data not shown). However, complete loss of the GP1 fragments to CatL digestion was associated with a profound reduction in viral infectivity. Thus, the degree of inactivation of each GP18K- or GP17K-containing virus could be predicted roughly by its susceptibility to CatL proteolysis. Importantly, in parallel samples incubated at pH 5.5 without CatL, no loss of GP1 was observed (Fig. 8A, lane N), and only small reductions in viral infectivity were obtained (Fig. 8B and C), providing evidence that proteolytic cleavage of the GP18K and GP17K intermediates, and not merely their incubation at acid pH, is required for viral inactivation.

Cleaved CA074R viruses require cysteine cathepsins for entry.

Our preceding observation that cleaved intermediates derived from a subset of the CA074R GPs appear to differ from their WT counterparts in conformation raised the possibility that viral particles containing these mutant intermediates no longer require cysteine cathepsin activity for entry. To test this hypothesis, WT and mutant rVSV-GPΔMuc were incubated with THL to generate the GP17K intermediate, and Vero cells pretreated with E-64 or with vehicle alone were challenged with the cleaved viral particles (Fig. 9). We found that infectivity of all of the cleaved mutant viruses resembled that of the WT in E-64-treated cells (reduced to <10% relative to a control infection). Thus, all of the CA074R GP17K intermediates must, like WT GP17K, undergo at least one additional cysteine cathepsin-dependent step during entry.

FIG. 9.

CA074R GP17K intermediates require cysteine cathepsin activity for entry. Vero cells were pretreated with 1% DMSO or 300 μM E64 for 4 h, challenged with the THL-derived WT or mutant rVSV-GP17K at an MOI of 0.001 FFU/cell, and then overlaid with agarose. Viral titers (FFU/ml) were determined at 18 hpi. Averages ± standard deviations from one representative experiment are shown. An aliquot of each cleaved virus was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and GP1 was detected by Western blotting to confirm GP cleavage. The higher mobility of GP1 fragments from N40K and T42A reflects their loss of N-glycan at N40. The position of the ∼17-kDa GP1 cleavage fragment is indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

The activity of the endosomal cysteine protease CatB is required for ZEBOV GP-mediated viral entry into Vero cells (Fig. 1 and 2) (14, 54). Here, we used an rVSV encoding ZEBOV GPΔMuc to select and characterize viral mutants capable of infecting Vero cells in the presence of the CatB inhibitor CA074 (Fig. 2 to 9). We found that CatB dependence is regulated by amino acid residues lining the GP1-GP2 subunit interface and by a nearby N-linked glycan (Fig. 5 and Table 1). We infer from differences in protease susceptibilities that some, but not all, CA074R GP18K and/or GP17K intermediates are conformationally distinct from their WT counterparts (Fig. 7 to 9). Our findings suggest multiple mechanisms for acquiring CatB independence (Fig. 10). They also suggest that WT GP18K→GP17K cleavage is required during entry for inducing conformational changes that destabilize the GP prefusion trimer. We speculate that this destabilization renders GP17K uniquely susceptible to a downstream triggering stimulus.

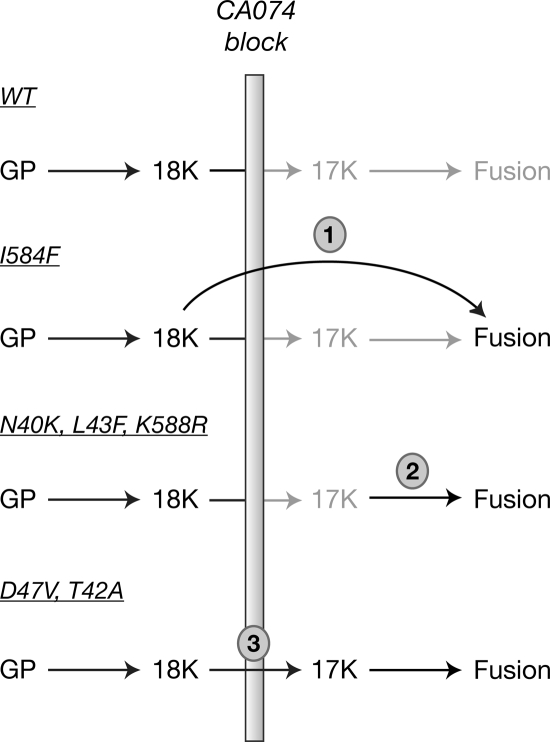

FIG. 10.

Models for CatB-independent cell entry mediated by the CA074R GPs. Schematic diagram of steps in ZEBOV GP-mediated viral entry is shown. Steps in entry arrested by the CA074 block are gray. WT GP is blocked at the GP18K→GP17K step (and consequently, at all downstream steps as well). 1, the I584F mutant is proposed to bypass this step because its conformationally altered GP18K is unstable enough to be triggered directly by an undefined mechanism. 2, the N40K, L43F, and K588R mutants are proposed to have less-stable GP17K intermediates with a lower threshold for fusion activation. This reduced stability may compensate for inefficient processing to the GP17K intermediate in the presence of CA074 by increasing the efficiency of GP17K fusion triggering. 3, the T42A and D47V mutants are proposed to use a protease other than CatB or CatL to efficiently generate GP17K. See text for additional details.

What are the critical molecular features of the GP17K intermediate, and why is CatB required to generate it?

CatB removes approximately 10 residues from the C terminus of the GP1 subunit during GP18K→GP17K conversion (Fig. 7) (18; K. Chandran, unpublished data). These residues lie within the large, disordered β13-β14 loop (connecting β-strands 13 and 14) that separates the GP1 base and glycan cap subdomains of the prefusion trimer (Fig. 5B) (39). The β13-β14 loop crosses over the GP2 β19-β20 hairpin that bears the hydrophobic fusion loop, providing a possible structural rationale for its removal during GP priming: the release of a covalent constraint on GP2 rearrangement. Accordingly, we predicted that one or more of the CA074R GPs would contain a mutation within this loop that allows its cleavage by a non-CatB cysteine cathepsin. Unexpectedly, all of the CA074R viruses instead contained mutations in the base of GP (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Our failure to obtain mutations in the GP1 β13-β14 loop may reflect that (i) our sampling of the CA074 resistance determinants in the viral quasispecies is incomplete; (ii) cleavage in the loop is not, in fact, the critical event mediated by CatB; (iii) multiple mutations are needed to render the β13-β14 loop cleavable by endosomal proteases other than CatB; or (iv) determinants of cleavage in the loop lie elsewhere in GP (see below).

The inability of CatL and other non-CatB cysteine cathepsins to remove a few disordered residues at the GP1 C terminus, despite their broad substrate preferences (5, 15, 52), may indicate steric constraints in GP that limit access to cleavage sites in the β13-β14 loop. Indeed, the capacity of CatB to processively cleave peptides from the C terminus (carboxypeptidase activity), unique to it and CatX/Z among the cysteine cathepsins (3, 36, 61), may account for its specific requirement in this case. Might one or more of the CA074R mutations then promote CatB-independent cleavage within the GP1 β13-β14 loop by alleviating these structural constraints? Our finding that neither CatL nor CHT could mediate the GP18K→GP17K cleavage for the CA074R mutants, but that CatB could, rules out a generalized increase in the capacity of non-CatB proteases to carry out the GP18K→GP17K step (Fig. 7). Experiments are under way to determine whether other enzymes active in Vero cells can substitute for CatB in mediating GP18K→GP17K cleavage during CA074R virus entry.

What are the structural consequences of the CA074R mutations for the prefusion GP trimer?

The locations of CA074R mutations in the prefusion GP structure indicate potential consequences distinct from any effects on the GP1 β13-β14 loop. Changes at N40 and T42 in the GP1 base subdomain, present in a majority of the isolated CA074R viruses, abolished N-linked glycosylation at N40, consistent with loss of the NXT glycosylation motif (Fig. 5 and 7 and Table 1). Comparison of the GP prefusion crystal structures of ZEBOV (lacking the N40 glycan) and Sudan EBOV (containing it) indicates that the presence or absence of this glycan does not significantly alter local protein conformation or GP1-GP2 interactions (39) (J. Dias and E. O. Saphire, personal communication). Instead of inducing changes in the prefusion conformation of GP, N40 glycan deletion may promote CatB independence by exposing previously buried cleavage sites in GP18K and/or GP17K. However, N40K and T42A, which both delete this glycan, nonetheless have distinct protease sensitivities (Fig. 8). Thus, it is possible that specific substitutions at these positions may alter GP conformation independent of the effects of glycan deletion at N40. Examination of the panel of CA074R mutants with different changes at N40 may resolve this issue (Table 1).

The other four CA074R mutations in GP1 (L43F and D47V) and GP2 (I584F and K588R) alter residues that line the GP1-GP2 interface. L43, I584, and K588 participate in hydrophobic interactions with aliphatic and aromatic residues in the GP1 base subdomain, an N-terminal segment of GP2 preceding the fusion loop region, and the GP2 trimer core (Fig. 5). Substitutions of aliphatic residues to the bulkier aromatic Phe (L43F and I584F) and of Lys to the bulkier Arg (K588R) may cause rearrangements that weaken these GP1-GP2 interactions. Residues D47 and K588 approach each other closely (<3.9 Å) but do not appear to form an intersubunit salt bridge. Introduction of an aliphatic residue within a charged region (D47V) and/or substitution with a larger residue (K588R) may also compromise GP1-GP2 interactions. Thus, at least four out of six CA074R mutations may serve to “loosen” the clamp holding GP2 in its prefusion conformation.

Behavior of CA074R mutants suggests a function for GP→GP17K cleavage in cell entry and a role for cysteine cathepsins in fusion triggering.

Why is GP→GP17K cleavage required for viral entry? It has been proposed that cleavage enhances the binding of GP to an endosomal receptor by uncovering receptor-binding sequences in the GP1 head subdomain that are recessed in the intact trimer (18, 34, 39). In support of this idea, GP→GP17K cleavage enhances virus-cell adhesion (34). However, a similar binding enhancement is obtained following GP→GP18K cleavage, concomitant with removal of the Muc and glycan cap sequences (34). Therefore, receptor binding cannot fully explain the specific requirement for a GP17K-like species during entry. We believe that our findings with the CA074R mutants provide a clue to an additional function of GP→GP17K cleavage when placed in the context of well-studied class I viral fusion mechanisms.

Studies of the prototypic class I fusion glycoprotein, influenza virus hemagglutinin, suggest that it is rendered metastable upon priming—that is, prevented from attaining its energetically favorable postfusion conformation by a kinetic barrier (12). Acid pH triggers fusion-related hemagglutinin rearrangement by lowering this barrier, but destabilization of the prefusion conformation by nonphysiological stimuli, such as heat or denaturants, can also drive membrane fusion (12). For both acid-triggered and receptor-triggered class I glycoproteins, selection of viral variants resistant to an entry inhibitor has yielded “hair trigger” mutations that appear to lower the activation barrier for fusion by destabilizing the prefusion conformation of the glycoprotein (2, 7, 49, 53). In this study, we obtained evidence consistent with the destabilizing effect of some CA074R mutations on the prefusion conformation of GP. Specifically, primed GP intermediates derived from some CA074R viruses were highly susceptible to proteolytic digestion and inactivation, whereas intermediates derived from the WT and other mutants were less protease sensitive (Fig. 8). Crucially, GP17K was more sensitive to proteolysis than GP18K in every case, including the WT. We surmise that the conformational changes in CA074R GP18K and/or GP17K that cause their enhanced susceptibility to proteolysis reflect an “opening up” of the prefusion structure that lowers the activation barrier for induction of fusion. If correct, then this hypothesis implies that GP18K→GP17K cleavage is required for WT virus entry because it performs the same destabilizing function. Finally, because all of the GP17K intermediates examined in this study must undergo an additional cysteine cathepsin-dependent step to mediate viral entry (Fig. 9), we speculate that the observed proteolytic cleavage of GP17K, with attendant viral inactivation, is directly relevant to the fusion triggering process.

How do the CA074R mutants acquire CatB independence?

We propose that the disparate behaviors of the CA074R mutants in the protease sensitivity assay reflect multiple scenarios for CA074 resistance (Fig. 10). In the first, the I584F mutation destabilizes the GP18K intermediate to such a degree that it can be triggered directly, allowing bypass of the GP18K→GP17K step entirely. In the second scenario (N40K, L43F, and K588R), only GP17K is sensitive to the fusion trigger, but this intermediate is much more efficiently triggered than the WT, allowing viral entry. Implicit in this model is the assumption that the CA074 block to GP18K→GP17K is not absolute, that is, it can be mediated at least inefficiently by residual CatB or an alternative protease. In the third (T42A and D47V), once again only GP17K is sensitive to fusion triggering, but there is no significant difference in triggering efficiency. Instead, we hypothesize that the mutants, unlike the WT, are capable of using proteases other than CatB to efficiently generate GP17K so that CA074 pretreatment has little or no effect on the GP18K→GP17K step. We are currently performing experiments to test these models.

What roles do CatL and other non-CatB cysteine cathepsins play in EBOV GP-dependent cell entry?

While the CatB requirement for ZEBOV GP-dependent entry into Vero cells has been confirmed in multiple studies, the roles of CatL and other cysteine cathepsins remain unclear. We originally showed that CatL is dispensable for ZEBOV GP-dependent entry into Vero cells but likely contributes by assisting CatB or other endosomal proteases to remove the Muc and glycan cap sequences in GP1 and possibly generate a GP18K-like species. As shown previously and described above, CatL cannot generate the critical GP17K intermediate. Following our initial study, two reports indicated that viral pseudotypes containing uncleaved GP, GP18K (34, 54), or GP17K (54) were all poorly infectious in Vero cells lacking CatL activity, suggesting that it is essential for a step in entry that is distinct from GP→GP17K cleavage. Here we demonstrate that CatL is dispensable for Vero cell entry by all VSVs tested, both pseudotype and recombinant, and bearing either the WT or CA074R GPΔMuc (Fig. 1 and 6). We believe that these apparent inconsistencies among the published reports result from differences in the concentrations and incubation times of protease inhibitors used to inactivate CatL within Vero cells in each study. Specifically, we found that the conditions used in references 34 and 54 not only inactivate CatL but also cause substantial off-target inactivation of CatB in cells (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, the inhibitor treatment conditions used in this study are selective for CatL (Fig. 1). We conclude that the strong inhibition of viral entry into Vero cells observed with CatL inhibitors in some previous studies is likely caused by the inactivation of CatB and non-CatB/CatL proteases. Importantly, recent work by Martinez et al. (43) demonstrates that these conclusions are not limited to VSV-GP particles or Vero cells; these authors showed that CatB is required for infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived dendritic cells by authentic ZEBOV and entry by virus-like particles bearing ZEBOV GP, whereas CatL is dispensable. However, neither our findings nor those of Martinez et al. (43) discount the possibility that CatL mediates one or more steps in viral entry redundantly with other cysteine cathepsins in Vero or dendritic cells. Moreover, CatL may be required in some physiologically relevant cell types that lack this functional redundancy.

Finally, we note that even the CatB requirement is likely not absolute among filoviruses; our preliminary studies indicate the existence of EBOV species-dependent differences in CatB dependence during VSV-GP entry into Vero cells (K. Chandran, unpublished data). While residues mutated in the CA074R viruses and their contacting partners are conserved largely among available EBOV GP sequences, interspecies polymorphisms do exist at several positions (e.g., D47E in EBOV Sudan and D47E and I584L in EBOV Reston) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and may at least partially explain the observed differences in CatB dependence.

Comparisons with other endosomal protease-dependent viral entry mechanisms.

In addition to filoviruses, there is a growing list of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses that are known to require endosomal proteases during entry. In many cases, proteolytic cleavage primes or deprotects the viral entry protein, generating an intermediate that can undergo triggered conformational rearrangement to expose membrane-interacting sequences. Analogous to furin-mediated priming of many class I viral fusion proteins, CatL-mediated cleavage of the Nipah paramyxovirus glycoprotein precursor, F0, to F1 plus F2 occurs in virus producer cells, liberating an N-terminal fusion peptide in F2 and sensitizing F for fusion triggering (48). Like EBOV GP, the nonenveloped mammalian reovirus capsid undergoes extensive proteolytic disassembly during entry; 600 copies of the σ3 protector protein are degraded by CatL and CatB to expose the μ1 penetration protein (8, 17, 19). Unlike the EBOV GP17K intermediate, the Nipah virus and reovirus intermediates no longer require cysteine protease activity to enter cells (1, 13, 57). Cysteine cathepsins appear to play a more complex role in entry of the severe acute respiratory syndrome and mouse hepatitis virus type 2 coronaviruses. Their S glycoproteins are cleaved by CatL in a receptor-dependent manner to trigger fusion (9, 29, 51, 55); however, cleavage may be needed not to promote the initial receptor-dependent rearrangement of S but to relieve a structural constraint (possibly related to fusion peptide release [6, 40]) that impedes completion of the fusion reaction (45, 55). For all of the cysteine cathepsin-dependent viruses except EBOV, experimental conditions can be arranged to allow cell entry in the presence of broad-spectrum cysteine cathepsin inhibitors (51, 55, 57). It is tempting to speculate that the unidentified cysteine protease-dependent step in EBOV entry is a GP cleavage that either triggers fusion or relieves a late block to membrane fusion initiated by another trigger, such as receptor binding. The ongoing failure to reconstitute robust GP-mediated membrane fusion likely reflects requirements for additional factors.

Utility of rVSVs encoding heterologous viral glycoproteins for forward genetic studies of viral entry.

Selection of drug-resistant variants within a viral population is a powerful strategy to investigate the drug's mechanism of action and the physiological process it targets. Unfortunately, this strategy has been utilized only in a limited way for filoviruses and other highly pathogenic enveloped viruses, because of the challenges inherent in working with the authentic agents. Two recent approaches allow forward genetic studies of cell entry by EBOV in lower-biocontainment facilities. The first is a replication-defective EBOV mutant engineered to lack the VP30 gene that can be propagated only in a complementing cell line (26). This approach is highly powerful because it affords analysis of all the viral genes, except VP30, in an authentic viral context. However, it is not yet widely available. The second approach, a recombinant VSV that encodes EBOV GP as its only entry glycoprotein, has been implemented by Takada et al. (58) and in the present study. The fidelity of rVSV-GP as an EBOV entry model was demonstrated by the Kawaoka and Feldmann groups, who obtained similar sets of neutralization escape mutants with EBOV ΔVP30 and rVSV-GP following selections with the same GP-recognizing antibody (26, 58). Other key advantages of the rVSV approach are its safety and flexibility; rVSVs bearing the glycoproteins from several emerging viruses, including marburgvirus (16, 23, 24, 32), Lassa fever virus (23, 25), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (35), are candidate live-attenuated vaccines with good safety profiles in mammals, and they should be amenable to genetic analysis. It should also be possible to engineer and rescue new recombinants with viral glycoproteins that generate high-titer VSV pseudotypes (e.g., Nipah and Hendra F plus G [33, 50]). Despite the potential utility of rVSVs for genetic selections, we could find only one previous report in which they were exploited for this purpose (58). Our findings argue for the more extensive use of rVSVs in forward genetic studies of enveloped virus entry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M.C. Kielian, J. E. Lee, E. H. Miller, and E. O. Saphire for helpful discussions and critical reviews of the manuscript, J. Dias and E. O. Saphire for sharing unpublished results, D. K. Cureton for advice on the design and rescue of rVSVs, and the other members of our laboratories. We are grateful to J. M. Cunningham for the gift of anti-GP1 antiserum.

This work was supported by NIH grant K22 AI074908 and institutional seed funds (to K.C.) and by an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to S.P.W.). A.C.W. was additionally supported by the Medical Scientist Training Program (NIH T32 GM007288) and the Geographic Medicine and Emerging Infections Training Program (NIH T32 AI070117) at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 October 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agosto, M. A., K. S. Myers, T. Ivanovic, and M. L. Nibert. 2008. A positive-feedback mechanism promotes reovirus particle conversion to the intermediate associated with membrane penetration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:10571-10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amberg, S. M., R. C. Netter, G. Simmons, and P. Bates. 2006. Expanded tropism and altered activation of a retroviral glycoprotein resistant to an entry inhibitor peptide. J. Virol. 80:353-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson, N. N., Jr., and A. J. Barrett. 1978. The specificity of cathepsin B. Hydrolysis of glucagon at the C-terminus by a peptidyldipeptidase mechanism. Biochem. J. 171:759-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascenzi, P., A. Bocedi, J. Heptonstall, M. R. Capobianchi, A. Di Caro, E. Mastrangelo, M. Bolognesi, and G. Ippolito. 2008. Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus: insight the Filoviridae family. Mol. Aspects Med. 29:151-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett, A. J., and H. Kirschke. 1981. Cathepsin B, Cathepsin H, and cathepsin L. Methods Enzymol. 80:535-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belouzard, S., V. C. Chu, and G. R. Whittaker. 2009. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:5871-5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyer, W. E., R. W. Ruigrok, H. van Driel, and N. Masurel. 1986. Influenza virus strains with a fusion threshold of pH 5.5 or lower are inhibited by amantadine. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 90:173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsa, J., T. P. Copps, M. D. Sargent, D. G. Long, and J. D. Chapman. 1973. New intermediate subviral particles in the in vitro uncoating of reovirus virions by chymotrypsin. J. Virol. 11:552-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch, B. J., W. Bartelink, and P. J. Rottier. 2008. Cathepsin L functionally cleaves the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus class I fusion protein upstream of rather than adjacent to the fusion peptide. J. Virol. 82:8887-8890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brindley, M. A., L. Hughes, A. Ruiz, P. B. McCray, A. Sanchez, D. A. Sanders, and W. Maury. 2007. Ebola virus glycoprotein 1: identification of residues important for binding and post binding events. J. Virol. 81:7702-7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter, A. E., T. R. Jones, M. R. Lamprecht, C. Clarke, I. H. Kang, O. Friman, D. A. Guertin, J. H. Chang, R. A. Lindquist, J. Moffat, P. Golland, and D. M. Sabatini. 2006. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7:R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr, C. M., C. Chaudhry, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14306-14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandran, K., D. L. Farsetta, and M. L. Nibert. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol. 76:9920-9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandran, K., N. J. Sullivan, U. Felbor, S. P. Whelan, and J. M. Cunningham. 2005. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science 308:1643-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe, Y., F. Leonetti, D. C. Greenbaum, F. Lecaille, M. Bogyo, D. Bromme, J. A. Ellman, and C. S. Craik. 2006. Substrate profiling of cysteine proteases using a combinatorial peptide library identifies functionally unique specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 281:12824-12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daddario-DiCaprio, K. M., T. W. Geisbert, J. B. Geisbert, U. Ströher, L. E. Hensley, A. Grolla, E. A. Fritz, F. Feldmann, H. Feldmann, and S. M. Jones. 2006. Cross-protection against Marburg virus strains by using a live, attenuated recombinant vaccine. J. Virol. 80:9659-9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dryden, K. A., G. Wang, M. Yeager, M. L. Nibert, K. M. Coombs, D. B. Furlong, B. N. Fields, and T. S. Baker. 1993. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 122:1023-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dube, D., M. B. Brecher, S. E. Delos, S. C. Rose, E. W. Park, K. L. Schornberg, J. H. Kuhn, and J. M. White. 2009. The primed ebolavirus glycoprotein (19-kilodalton GP1,2): sequence and residues critical for host cell binding. J. Virol. 83:2883-2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebert, D. H., J. Deussing, C. Peters, and T. S. Dermody. 2002. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24609-24617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldmann, H., T. Geisbert, and Y. Kawaoka. 2007. Filoviruses: recent advances and future challenges. J. Infect. Dis. 196(Suppl. 2):S129-S130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldmann, H., T. W. Geisbert, P. B. Jahrling, H. D. Klenk, S. Netsov, C. Peters, A. Sanchez, R. Swanepoel, and V. E. Volchkov. 2005. Virus taxonomy. Eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 22.Gallaher, W. R. 1996. Similar structural models of the transmembrane proteins of Ebola and avian sarcoma viruses. Cell 85:477-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garbutt, M., R. Liebscher, V. Wahl-Jensen, S. Jones, P. Möller, R. Wagner, V. Volchkov, H. D. Klenk, H. Feldmann, and U. Ströher. 2004. Properties of replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing glycoproteins of filoviruses and arenaviruses. J. Virol. 78:5458-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisbert, T. W., J. B. Geisbert, A. Leung, K. M. Daddario-DiCaprio, L. E. Hensley, A. Grolla, and H. Feldmann. 2009. Single-injection vaccine protects nonhuman primates against infection with Marburg virus and three species of Ebola virus. J. Virol. 83:7296-7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisbert, T. W., S. Jones, E. A. Fritz, A. C. Shurtleff, J. B. Geisbert, R. Liebscher, A. Grolla, U. Stroher, L. Fernando, K. M. Daddario, M. C. Guttieri, B. R. Mothe, T. Larsen, L. E. Hensley, P. B. Jahrling, and H. Feldmann. 2005. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever. PLoS Med. 2:e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halfmann, P., J. H. Kim, H. Ebihara, T. Noda, G. Neumann, H. Feldmann, and Y. Kawaoka. 2008. Generation of biologically contained Ebola viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:1129-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallenberger, S., V. Bosch, H. Angliker, E. Shaw, H. D. Klenk, and W. Garten. 1992. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature 360:358-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison, S. C. 2008. Viral membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:690-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, I. C., B. J. Bosch, F. Li, W. Li, K. H. Lee, S. Ghiran, N. Vasilieva, T. S. Dermody, S. C. Harrison, P. R. Dormitzer, M. Farzan, P. J. Rottier, and H. Choe. 2006. SARS coronavirus, but not human coronavirus NL63, utilizes cathepsin L to infect ACE2-expressing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281:3198-3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito, H., S. Watanabe, A. Sanchez, M. A. Whitt, and Y. Kawaoka. 1999. Mutational analysis of the putative fusion domain of Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 73:8907-8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffers, S. A., D. A. Sanders, and A. Sanchez. 2002. Covalent modifications of the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 76:12463-12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones, S. M., H. Feldmann, U. Stroher, J. B. Geisbert, L. Fernando, A. Grolla, H. D. Klenk, N. J. Sullivan, V. E. Volchkov, E. A. Fritz, K. M. Daddario, L. E. Hensley, P. B. Jahrling, and T. W. Geisbert. 2005. Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses. Nat. Med. 11:786-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaku, Y., A. Noguchi, G. A. Marsh, J. A. McEachern, A. Okutani, K. Hotta, B. Bazartseren, S. Fukushi, C. C. Broder, A. Yamada, S. Inoue, and L. F. Wang. 2009. A neutralization test for specific detection of Nipah virus antibodies using pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus expressing green fluorescent protein. J. Virol. Methods 160:7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaletsky, R. L., G. Simmons, and P. Bates. 2007. Proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoproteins enhances virus binding and infectivity. J. Virol. 81:13378-13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapadia, S. U., J. K. Rose, E. Lamirande, L. Vogel, K. Subbarao, and A. Roberts. 2005. Long-term protection from SARS coronavirus infection conferred by a single immunization with an attenuated VSV-based vaccine. Virology 340:174-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klemencic, I., A. K. Carmona, M. H. Cezari, M. A. Juliano, L. Juliano, G. Guncar, D. Turk, I. Krizaj, V. Turk, and B. Turk. 2000. Biochemical characterization of human cathepsin X revealed that the enzyme is an exopeptidase, acting as carboxymonopeptidase or carboxydipeptidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:5404-5412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuhn, J. H. 2008. Filoviruses. A compendium of 40 years of epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory studies. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 20:13-360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhn, J. H., S. R. Radoshitzky, A. C. Guth, K. L. Warfield, W. Li, M. J. Vincent, J. S. Towner, S. T. Nichol, S. Bavari, H. Choe, M. J. Aman, and M. Farzan. 2006. Conserved receptor-binding domains of Lake Victoria marburgvirus and Zaire ebolavirus bind a common receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281:15951-15958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, J. E., M. L. Fusco, A. J. Hessell, W. B. Oswald, D. R. Burton, and E. O. Saphire. 2008. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 454:177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madu, I. G., S. L. Roth, S. Belouzard, and G. R. Whittaker. 2009. Characterization of a highly conserved domain within the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein S2 domain with characteristics of a viral fusion peptide. J. Virol. 83:7411-7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malashkevich, V. N., B. J. Schneider, M. L. McNally, M. A. Milhollen, J. X. Pang, and P. S. Kim. 1999. Core structure of the envelope glycoprotein GP2 from Ebola virus at 1.9-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2662-2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manicassamy, B., J. Wang, H. Jiang, and L. Rong. 2005. Comprehensive analysis of Ebola virus GP1 in viral entry. J. Virol. 79:4793-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez, O., J. Johnson, B. Manicassamy, L. Rong, G. G. Olinger, L. E. Hensley, and C. F. Basler. 2009. Zaire Ebola virus entry into human dendritic cells is insensitive to cathepsin L inhibition. Cell. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Martinez, O., C. Valmas, and C. F. Basler. 2007. Ebola virus-like particle-induced activation of NF-kappaB and Erk signaling in human dendritic cells requires the glycoprotein mucin domain. Virology 364:342-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuyama, S., and F. Taguchi. 2009. Two-step conformational changes in a coronavirus envelope glycoprotein mediated by receptor binding and proteolysis. J. Virol. 83:11133-11141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neumann, G., T. W. Geisbert, H. Ebihara, J. B. Geisbert, K. M. Daddario-DiCaprio, H. Feldmann, and Y. Kawaoka. 2007. Proteolytic processing of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is not critical for Ebola virus replication in nonhuman primates. J. Virol. 81:2995-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nibert, M. L., and B. N. Fields. 1992. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein mu 1/mu 1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J. Virol. 66:6408-6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pager, C. T., W. W. Craft, J. Patch, and R. E. Dutch. 2006. A mature and fusogenic form of the Nipah virus fusion protein requires proteolytic processing by cathepsin L. Virology 346:251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Platt, E. J., J. P. Durnin, U. Shinde, and D. Kabat. 2007. An allosteric rheostat in HIV-1 gp120 reduces CCR5 stoichiometry required for membrane fusion and overcomes diverse entry limitations. J. Mol. Biol. 374:64-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porotto, M., P. Carta, Y. Deng, G. E. Kellogg, M. Whitt, M. Lu, B. A. Mungall, and A. Moscona. 2007. Molecular determinants of antiviral potency of paramyxovirus entry inhibitors. J. Virol. 81:10567-10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu, Z., S. T. Hingley, G. Simmons, C. Yu, J. Das Sarma, P. Bates, and S. R. Weiss. 2006. Endosomal proteolysis by cathepsins is necessary for murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus type 2 spike-mediated entry. J. Virol. 80:5768-5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rawlings, N. D., F. R. Morton, C. Y. Kok, J. Kong, and A. J. Barrett. 2008. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D320-D325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruigrok, R. W., S. R. Martin, S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, P. M. Bayley, and D. C. Wiley. 1986. Conformational changes in the hemagglutinin of influenza virus which accompany heat-induced fusion of virus with liposomes. Virology 155:484-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schornberg, K., S. Matsuyama, K. Kabsch, S. Delos, A. Bouton, and J. White. 2006. Role of endosomal cathepsins in entry mediated by the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 80:4174-4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simmons, G., D. N. Gosalia, A. J. Rennekamp, J. D. Reeves, S. L. Diamond, and P. Bates. 2005. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:11876-11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simmons, G., J. D. Reeves, C. C. Grogan, L. H. Vandenberghe, F. Baribaud, J. C. Whitbeck, E. Burke, M. J. Buchmeier, E. J. Soilleux, J. L. Riley, R. W. Doms, P. Bates, and S. Pöhlmann. 2003. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind ebola glycoproteins and enhance infection of macrophages and endothelial cells. Virology 305:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sturzenbecker, L. J., M. Nibert, D. Furlong, and B. N. Fields. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 61:2351-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takada, A., H. Feldmann, U. Stroeher, M. Bray, S. Watanabe, H. Ito, M. McGregor, and Y. Kawaoka. 2003. Identification of protective epitopes on ebola virus glycoprotein at the single amino acid level by using recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Virol. 77:1069-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takada, A., K. Fujioka, M. Tsuiji, A. Morikawa, N. Higashi, H. Ebihara, D. Kobasa, H. Feldmann, T. Irimura, and Y. Kawaoka. 2004. Human macrophage C-type lectin specific for galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine promotes filovirus entry. J. Virol. 78:2943-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takada, A., C. Robison, H. Goto, A. Sanchez, K. G. Murti, M. A. Whitt, and Y. Kawaoka. 1997. A system for functional analysis of Ebola virus glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14764-14769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Therrien, C., P. Lachance, T. Sulea, E. O. Purisima, H. Qi, E. Ziomek, A. Alvarez-Hernandez, W. R. Roush, and R. Ménard. 2001. Cathepsins X and B can be differentiated through their respective mono- and dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase activities. Biochemistry 40:2702-2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Towner, J. S., T. K. Sealy, M. L. Khristova, C. G. Albarino, S. Conlan, S. A. Reeder, P. L. Quan, W. I. Lipkin, R. Downing, J. W. Tappero, S. Okware, J. Lutwama, B. Bakamutumaho, J. Kayiwa, J. A. Comer, P. E. Rollin, T. G. Ksiazek, and S. T. Nichol. 2008. Newly discovered ebola virus associated with hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Uganda. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Volchkov, V. E., H. Feldmann, V. A. Volchkova, and H. D. Klenk. 1998. Processing of the Ebola virus glycoprotein by the proprotein convertase furin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5762-5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watanabe, S., A. Takada, T. Watanabe, H. Ito, H. Kida, and Y. Kawaoka. 2000. Functional importance of the coiled-coil of the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 74:10194-10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]