Abstract

Andes virus (ANDV) causes a fatal hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) in humans and Syrian hamsters. Human αvβ3 integrins are receptors for several pathogenic hantaviruses, and the function of αvβ3 integrins on endothelial cells suggests a role for αvβ3 in hantavirus directed vascular permeability. We determined here that ANDV infection of human endothelial cells or Syrian hamster-derived BHK-21 cells was selectively inhibited by the high-affinity αvβ3 integrin ligand vitronectin and by antibodies to αvβ3 integrins. Further, antibodies to the β3 integrin PSI domain, as well as PSI domain polypeptides derived from human and Syrian hamster β3 subunits, but not murine or bovine β3, inhibited ANDV infection of both BHK-21 and human endothelial cells. These findings suggest that ANDV interacts with β3 subunits through PSI domain residues conserved in both Syrian hamster and human β3 integrins. Sequencing the Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domain revealed eight differences between Syrian hamster and human β3 integrins. Analysis of residues within the PSI domains of human, Syrian hamster, murine, and bovine β3 integrins identified unique proline substitutions at residues 32 and 33 of murine and bovine PSI domains that could determine ANDV recognition. Mutagenizing the human β3 PSI domain to contain the L33P substitution present in bovine β3 integrin abolished the ability of the PSI domain to inhibit ANDV infectivity. Conversely, mutagenizing either the bovine PSI domain, P33L, or the murine PSI domain, S32P, to the residue present human β3 permitted PSI mutants to inhibit ANDV infection. Similarly, CHO cells transfected with the full-length bovine β3 integrin containing the P33L mutation permitted infection by ANDV. These findings indicate that human and Syrian hamster αvβ3 integrins are key receptors for ANDV and that specific residues within the β3 integrin PSI domain are required for ANDV infection. Since L33P is a naturally occurring human β3 polymorphism, these findings further suggest the importance of specific β3 integrin residues in hantavirus infection. These findings rationalize determining the role of β3 integrins in hantavirus pathogenesis in the Syrian hamster model.

Hantaviruses persistently infect specific small mammal hosts and are spread to humans by the inhalation of aerosolized excreted virus (41, 42). Hantaviruses predominantly infect endothelial cells and cause one of two vascular leak-based diseases: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (41). Hantavirus diseases are characterized by increased vascular permeability and acute thrombocytopenia in the absence of endothelial cell lysis (36, 41, 42, 54). In general, hantaviruses are not spread from person to person; however, the Andes hantavirus (ANDV) is an exception, since there are several reports of person-to-person transmission of ANDV infection (11, 37, 47, 52). ANDV is also unique in its ability to cause an HPS-like disease in Syrian hamsters and serves as the best-characterized hantavirus disease model with a long onset, symptoms, and pathogenesis nearly identical to that of HPS patients (20, 21, 50).

Hantavirus infection of the endothelium alters endothelial cell barrier functions through direct and immunological responses (8, 14). Although the means by which hantaviruses cause pulmonary edema or hemorrhagic disease has been widely conjectured, the mechanisms by which hantaviruses elicit pathogenic human responses have yet to be defined. Hantaviruses coat the surface of infected VeroE6 cells days after infection (17), and this further suggests that dynamic hantavirus interactions with immune and endothelial cells are likely to contribute to viral pathogenesis. Hantavirus pathogenesis has been suggested to involve CD8+ T cells, tumor necrosis factor alpha or other cytokines, viremia, and the dysregulation of β3 integrins (7, 8, 13-16, 25-28, 32, 34, 38, 44-46). However, these responses have not been demonstrated to contribute to hantavirus pathogenesis, and in some cases there are conflicting data on their involvement (18, 25-28, 34, 35, 44, 45, 48). Immune complex deposition clearly contributes to HFRS patient disease and renal sequelae (4, 7), but it is unclear what triggers vascular permeability in HPS and HFRS diseases or why hemorrhage occurs in HFRS patients but not in HPS patients (8, 36, 54). Acute thrombocytopenia is common to both diseases, and platelet dysfunction resulting from defective platelet aggregation is reported in HFRS patients (7, 8).

Pathogenic hantaviruses have in common their ability to interact with αIIbβ3 and αvβ3 integrins present on platelets and endothelial cells (13, 16), and β3 integrins have primary roles in regulating vascular integrity (1, 2, 6, 19, 22, 39, 40). Consistent with the presence of cell surface displayed virus (17), pathogenic hantaviruses uniquely block αvβ3 directed endothelial cell migration and enhance endothelial cell permeability for 3 to 5 days postinfection (14, 15). Pathogenic hantaviruses dysregulate β3 integrin functions by binding domains present at the apex of inactive β3 integrin conformers (38). αvβ3 forms a complex with vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and normally regulates VEGF-directed endothelial cell permeability (2, 3, 10, 39, 40). However, both β3 integrin knockouts and hantavirus-infected endothelial cells result in increased VEGF-induced permeability, presumably by disrupting VEGFR2-β3 integrin complex formation (2, 14, 19, 39, 40). This suggests that at least one means for hantaviruses to increase vascular permeability occurs through interactions with β3 integrins that are required for normal platelet and endothelial cell functions.

αvβ3 and αIIbβ3 integrins exist in two conformations: an active extended conformation where the ligand binding head domain is present at the apex of the heterodimer and a basal, inactive bent conformation where the globular head of the integrin is folded toward the cell membrane (30, 53, 55). Pathogenic HTN and NY-1 hantaviruses bind to the N-terminal plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain of β3 integrin subunits and are selective for bent, inactive αvβ3 integrin conformers (38). Pathogenic hantavirus binding to inactive αvβ3 integrins is consistent with the selective inhibitory effect of hantaviruses on αvβ3 function and endothelial cell permeability (14, 15, 38). Although the mechanism of hantavirus induced vascular permeability has yet to be defined, there is a clear role for β3 integrin dysfunction in vascular permeability deficits (5, 6, 22, 29, 39, 40, 51) which make an understanding of hantavirus interactions with β3 subunits important for both entry and disease processes.

The similarity between HPS disease in humans and Syrian hamsters (20, 21) suggests that pathogenic mechanisms of ANDV disease are likely to be coincident. Curiously, other hantaviruses (Sin Nombre virus [SNV] and Hantaan virus [HTNV]) are restricted in Syrian hamsters and fail to cause disease in this animal, even though they are prominent causes of human disease (50). Although the host range restriction for SNV and HTNV in Syrian hamsters has not been defined (33), the pathogenesis of ANDV in Syrian hamsters suggests that both human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins may similarly be used by ANDV and contribute to pathogenesis.

We demonstrate here that ANDV infection of the Syrian hamster BHK-21 cell line and human endothelial cells is dependent on αvβ3 and inhibited by αvβ3 specific ligands and antibodies. Further, polypeptides expressing the N-terminal 53 residues of human and Syrian hamster β3 subunits block ANDV infection. This further indicates that ANDV interaction with the N-terminal 53 residues of both human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins is required for viral entry. We also demonstrate that ANDV recognition of human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins is determined by proline substitutions at residues 32/33 within the β3 integrin PSI domain. These results define unique ANDV interactions with human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

VeroE6 cells, CHO cells, and BHK-21 cells (ATCC CRL 1586, CCL 61, and CCL-10) were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; 56°C inactivated), penicillin (100 μg/ml), streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (50 μg/ml) (Gibco). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Clonetics) were grown in supplemented endothelial cell basal medium-2 (EBM-2; Clonetics) in the presence of gentamicin (50 μg/ml), amphotericin B (50 μg/ml), and 2% FCS (Clonetics). Andes virus (CH1-7913) (12) was kindly provided by B. Hjelle (University of New Mexico). ANDV and NY-1V were grown as previously described (14) in a biosafety level 3 facility. Briefly, viruses were adsorbed onto VeroE6 monolayers for 1 h, washed, and grown in DMEM containing 2% FCS.

Ligands and antibodies.

Fibronectin, collagen, laminin, and chondroitin sulfate were purchased from Sigma and vitronectin was obtained from Chemicon. Polyclonal rabbit antisera to α1 (antibody 1934), α2 (antibody 1936), β3 (antibody 1932), α5β1 (antibody 1950), and blocking monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to β2 (MAb 1962) and αvβ3 (MAbs 1976, LM609) were purchased from Chemicon. Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate and fluorescein-labeled Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G(H+L) were from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc. The generation of rabbit antisera to the hantavirus nucleocapsid protein was previously described (16).

Plasmids and proteins.

cDNA coding regions for human β3 and αv, murine β3, and bovine β3 integrin subunits were previously cloned in pcDNA3.1(−)/ZEO (38). Bovine β3 P33L, human β3 L33P, and murine S32P mutants were generated by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) and sequenced. Clones containing residues 1 to 53 of human β3, bovine β3, bovine β3 P33L, and murine β3 were subcloned from full-length human, bovine, and murine β3 plasmids into pET6His (9) at the BamHI/EcoRI site as previously described (38). IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction (1 mM for 3 h) of pET6His plasmid in BL21(DE3) cells was used to express β3 polypeptides containing residues 1 to 53 and performed at 30°C as previously described (38). Briefly, bacterial pellets were resuspended in 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, and 1 M urea, sonicated, and purified on Ni2+-NTA resin (Qiagen) (38). Proteins were eluted with 50 mM EDTA and dialyzed overnight in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 3.5-kDa cutoff), and protein concentrations were quantitated by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce).

Cloning and sequencing of Syrian hamster β3 integrin subunit.

Total RNA was extracted from Syrian hamster cell line BHK-21 and Syrian hamster liver tissue (RNeasy; Qiagen). RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA (Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis; Roche) (25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 95°C for 5 min) by using primers containing consensus β3 integrin subunit sequences derived from human, murine, rat, and rabbit β3 integrins (GenBank accession numbers NM_00012, NM_016780, NM_153720, and NM_001082066, respectively): antisense primers 5′-ATCACAKACTGTAGCCTGCATGATGGC-3′ (ending at bp 777 of the human β3 integrin sequence) and 5′-AGCACRTGTTTGTAGCCAAACATGGG-3′ (ending at bp 659 of the human β3 integrin sequence) (R = A or G; K = T or G). cDNA was subjected to nested PCR by using the forward primer 5′-CTGGCGCTGGGGGCGCTGGCGGGCGT-3′ starting at bp 43 of the human β3 integrin sequence and the reverse primer 5′-TCCACRAAKGCCCCRAAGCCAATCCG-3′ starting at bp 526 of the human β3 integrin sequence (cycle 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s). Amplified cDNA fragments were ligated into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen), transformed into XL1-Blue cells, and sequenced. The region corresponding to the N-terminal 53 residues of human β3 integrin was subcloned into pET6His vector at the BamHI/EcoRI site, transformed into BL21(DE3) cells, and subsequently expressed as described above.

Ligand and antibody pretreatment of cells.

HUVECs, VeroE6 cells, and BHK-21 cells were pretreated with antibodies (0.1 to 1 μg/ml) or potentially competitive ligands (5 to 20 μg/ml) for 1 h at 4°C. Antibodies and ligands were preadsorbed to cells in 50 μl of DMEM with 2% FCS in duplicate wells of a 96-well plate on ice. Sera or ligands were removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Approximately 1,000 focus-forming units (FFU) of hantavirus were adsorbed to monolayers for 1 h at 37°C. Unbound virus was removed, monolayers were washed three times with PBS, and infected monolayers were incubated 24 h prior to methanol fixation (100% methanol, 30 min at −20°C).

Polypeptide Inhibition of ANDV and NY-1V Infection.

Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg/ml) of human, murine (negative control), S32P murine mutant, bovine, P33L bovine mutant, Syrian hamster, or N39D Syrian hamster mutant β3 polypeptides (residues 1 to 53) were incubated with approximately 1,000 FFU of ANDV or NY-1V (2 h at 4°C) and then adsorbed to HUVECs, VeroE6 cells, or BHK-21 cells in duplicate wells (96-well plate, 100 μl per well) for 1 h at 37°C. Monolayers were washed with PBS, and the cells were incubated for 24 h prior to methanol fixation. Infected cells were detected by immunoperoxidase staining using anti-nucleocapsid antibody and quantitated as previously described (16).

Transfection and infection.

CHO cells were transfected (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen) as recommended with equal amounts of human αv and either human β3 or bovine β3 expression plasmids (pcDNA3.1) (38). At 2 days posttransfection, transfected CHO cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and the cells were dissociated with enzyme-free PBS-based cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen). Cells were resuspended in 100 μl of PBS and 2% FCS and incubated with anti-αvβ3 (MAb 1976) (2 μg/106 cells) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were pelleted (1,000 rpm for 2 min), washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and incubated with anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were repelleted, washed twice with ice-cold PBS plus 2% FCS, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and subjected to flow cytometry (FACSCalibur cell sorter; BD Biosciences). The geometric mean titer of β3 integrin fluorescence on CHO cells was used as a measure of integrin expression levels (15), and only cells expressing comparable levels of human or bovine β3 integrins were used in ANDV infection experiments. Transfected and mock-transfected CHO cells were infected with ANDV 48 h posttransfection as described above. Cells were methanol fixed after 24 h and immunoperoxidase stained for hantavirus nucleocapsid protein, and the number of infected cells was quantitated by microscopy as previously described (16).

RESULTS

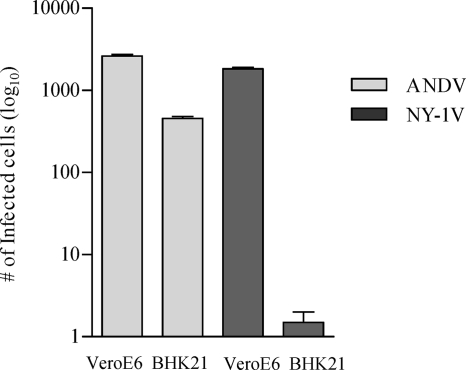

Syrian hamsters infected with ANDV develop a lethal disease with onset, symptoms, and respiratory distress similar to that of HPS patients (20, 21, 50). To date, all pathogenic hantaviruses have been demonstrated to use β3 integrins for cellular entry and pathogenic hantaviruses inhibit β3 functions days after infection (13-16, 38). However, ANDV interactions with human or Syrian hamster β3 integrins have not been defined, and the role of β3 integrins in regulating endothelial barrier functions provides a rationale for integrin regulation to contribute to viral pathogenesis. We investigated here whether ANDV interacts with human or Syrian hamster β3 integrins and defined residues required for ANDV infection. Initially, we evaluated the ability of ANDV to infect BHK-21 cells that are derived from Syrian hamsters. Figure 1 indicates that BHK-21 cells are highly infected by ANDV, although at a slightly reduced level from the identical infection of VeroE6 cells. However, there was a nearly 3-log reduction in NY-1V infection of BHK-21 cells compared to VeroE6 cells (Fig. 1). This result suggests a fundamental difference in ANDV infection of Syrian hamster cells from that of NY-1V, and this could result from differences in adherence to β3 integrins.

FIG. 1.

Infection of BHK21 and VeroE6 cells by ANDV and NY-1V. BHK21 cells and VeroE6 cells were identically infected with ANDV and NY-1V at an MOI of 0.5. The number of hantavirus-infected cells was quantitated 3 days postinfection by immunoperoxidase staining of the viral nucleocapsid protein.

In order to determine whether ANDV uses β3 integrins, we evaluated whether integrin ligands or antibodies inhibited ANDV infection of VeroE6 and BHK-21 cells. Pretreating cells with increasing amounts of collagen, chondroitin sulfate, laminin, or fibronectin had no effect on ANDV infection. In contrast, pretreating VeroE6 cells (Fig. 2A) and BHK-21 cells (Fig. 2B) with vitronectin, a high-affinity αvβ3 ligand, inhibited ANDV infection by 80 and 70%, respectively. Since antibodies that recognize Syrian hamster β3 integrins are not available, we investigated the ability of antibodies to human β3 integrins to inhibit ANDV infection. Figure 3 shows that pretreating cells with antibodies to human β3 or αvβ3 dose dependently inhibited ANDV infection of HUVECs and VeroE6 cells (85 and 70%, respectively; Fig. 3). Antibodies to the αv integrin subunit also reduced ANDV infection of HUVECs and VeroE6 cells (40 to 60%) (Fig. 3), whereas antibodies to α1, α5β1, α2, β2, and β5 had no inhibitory effect on ANDV infection. These results indicate that ligands or antibodies specific to αvβ3 integrins mediate ANDV entry into human, simian, and Syrian hamster cells.

FIG. 2.

Ligand-specific inhibition of ANDV infection. Potentially competitive ligands (5 to 20 μg/ml) were adsorbed to VeroE6 (A) and Syrian hamster BHK-21 (B) cells for 1 h at 4°C prior to virus addition. Approximately 1,000 FFU of ANDV were adsorbed for 1 h at 37°C to duplicate wells of a 96-well plate. After viral adsorption, inocula were removed, and the cells were washed and incubated 24 h at 37°C before methanol fixation. ANDV-infected cells were identified by immunoperoxidase staining of the viral nucleocapsid protein and quantitated by microscopy as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the controls.

FIG. 3.

ANDV infectivity is inhibited by integrin-specific antibodies. Duplicate wells with VeroE6 cells (A) and HUVECs (B) were pretreated for 1 h at 4°C with 0.01 to 1 μg of antibodies to the indicated integrins or integrin subunits prior to viral adsorption. Monolayers were washed with PBS, and ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV were adsorbed to cells for 1 h at 37°C. The inocula were removed, and the number of ANDV-infected cells was quantitated as previously described (16). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the controls.

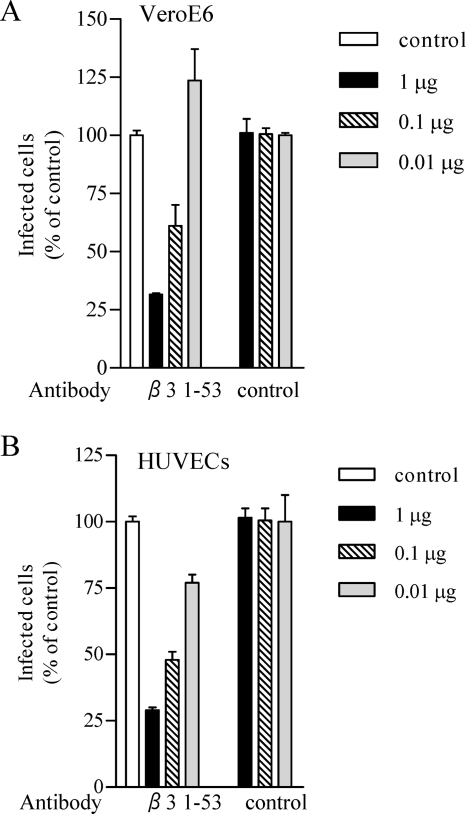

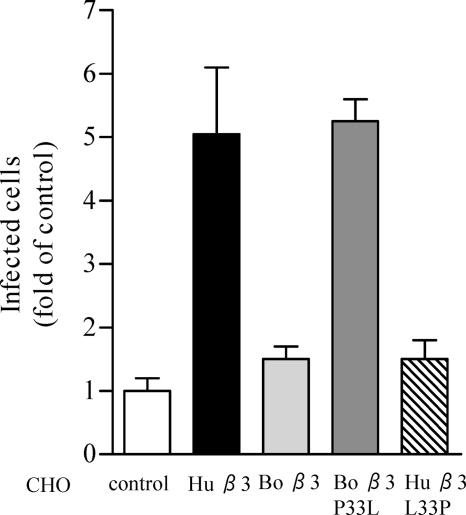

Binding of the NY-1V to β3 integrins was previously shown to be RGD independent, mediated by the N-terminal PSI domain present on human but not murine β3 integrin subunits, and dependent on an aspartic acid at position 39 (16, 38). In order to determine whether ANDV interacts with human β3 integrin PSI domains, we determined whether the expressed β3 integrin PSI domain (residues 1 to 53) or antibody to the PSI domain (residues 17 to 48) inhibited ANDV infection. Pretreating VeroE6 cells (Fig. 4A) and HUVECs (Fig. 4B) with antibodies against the human β3 integrin PSI domain resulted in a 70% decrease in ANDV infection compared to control antibodies. Similarly, pretreating ANDV with increasing amounts of the expressed human β3 PSI domain reduced ANDV infection of HUVECs by 75% (Fig. 5A) and ANDV infection of BHK-21 cells by 85% (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the murine β3 integrin PSI domain had no apparent effect on ANDV infection of either cell type.

FIG. 4.

Antibodies to human β3 integrin PSI domain inhibit ANDV infection. Duplicate wells of VeroE6 cells (A) or HUVECs (B) were pretreated for 1 h at 4°C with 0.01 to 1 μg of preimmune antibody or rabbit antibodies generated to a peptide containing residues 17 to 48 of the human β3 integrin PSI domain. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS, and ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV were adsorbed to monolayers in duplicate wells of a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. After viral adsorption, the inocula were removed, and the cells were washed and incubated 24 h at 37°C before methanol fixation. The number of ANDV-infected cells was quantitated by immunoperoxidase staining of the hantavirus nucleocapsid protein as previously described (16). The results were reproduced in two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the untreated controls.

FIG. 5.

Human β3 integrin PSI domain polypeptides inhibit ANDV infection. Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg) of expressed, and purified polypeptides containing residues 1 to 53 of human or murine β3 integrins were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV. Virus was subsequently adsorbed to HUVECs (A) or BHK-21 cells (B) in 96-well plates for 1 h at 37°C. Monolayers were washed with PBS, and at 1 day postinfection the number of ANDV-infected cells was quantitated after methanol fixation and immunoperoxidase staining of the hantavirus nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the mock-treated controls.

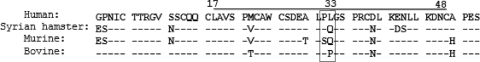

In order to determine whether Syrian hamster β3 integrins also blocked ANDV infection, we cloned and expressed the β3 integrin PSI domain from BHK-21 cells. Five independent clones of the Syrian hamster β3 integrin were sequenced and found to be identical to the cDNA sequenced from Syrian hamster tissue (submitted to GenBank). Figure 6 compares Syrian hamster β3 integrin coding sequences with human, murine, and bovine β3 PSI domains. The Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domain differs from the human sequence by eight residues. In contrast, murine and bovine PSI domains, which do not confer hantavirus infectivity, differ by 9 and 4 residues, respectively, from human PSI domains, whereas murine sequences differ by five residues from the Syrian hamster PSI domain (positions 30, 32, 42, 43, and 50).

FIG. 6.

Alignment of human, Syrian hamster, murine, and bovine β3 integrin PSI domains. Amino acid sequences of residues 1 to 53 from human, Syrian hamster, murine, and bovine β3 integrin (GenBank accession no. XM_616376) subunits are comparatively presented. Residue differences observed in β3 integrin homologues that differ from human β3 sequences are indicated, and dashes indicate identical residues. Residues 17 to 48 are delineated by a line, and proline residue differences at positions 32 and 33 of the β3 integrin homologues are boxed.

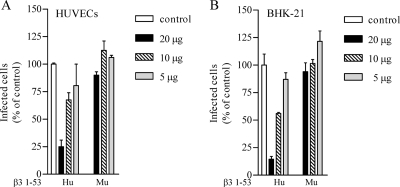

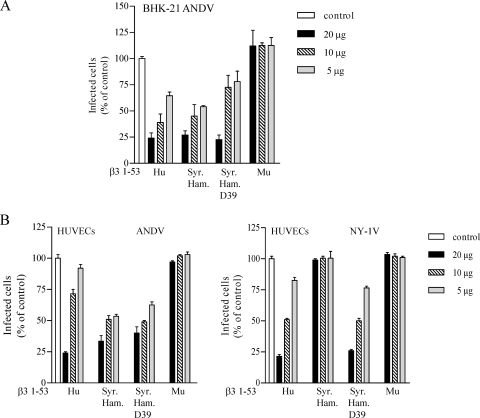

We further evaluated whether the expressed Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domain inhibited ANDV infection. Figure 7A indicates that pretreating ANDV with the Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domain (1 to 53) reduced ANDV infection of BHK-21 cells by 80%, similar to the human β3 integrin PSI domain (1 to 53). In contrast, the murine β3 PSI domain had no effect on ANDV infection of BHK-21 cells at any concentration. This indicates that both the Syrian hamster and human β3 integrin interact with ANDV. Since we previously demonstrated that the presence of an N or D residue at position 39 of β3 differentiated NY-1V interaction with β3 (38), we evaluated the effect of mutating residue 39 of the Syrian hamster β3 PSI domain from N to D. Figure 7A indicates that there was no difference in PSI domain inhibition of ANDV by the N39D mutant. This suggested a fundamental difference in the interaction of β3 with ANDV and NY-1V.

FIG. 7.

Human β3 and Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domain inhibit ANDV infection. (A) Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg) of expressed human (Hu), Syrian hamster (Syr. Ham.), Syrian hamster N39D mutant (D39), or murine (Mu) β3 integrin PSI domain polypeptides were incubated with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV for 2 h at 4°C. Virus was subsequently adsorbed to BHK-21 cells in a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. At 24 h postinfection, monolayers were immunoperoxidase stained for nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). (B) Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg) of human (Hu), Syrian hamster (Syr. Ham.) N39, Syrian hamster D39, and murine (Mu) β3 integrin PSI domain were incubated with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV or NY-1V for 2 h at 4°C. Virus was adsorbed to HUVECs in a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. At 24 h postinfection ANDV- or NY-1V-infected cells were quantitated by immunoperoxidase staining of the nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the mock-treated controls.

In order to determine whether the Syrian hamster β3 or the N39D Syrian hamster β3 mutant inhibited NY-1V infectivity, we comparatively evaluated the ability of the NY-1V and ANDV to infect HUVECs in the presence or absence of β3 PSI domains. Figure 7B demonstrates that the human and Syrian hamster β3 PSI domains inhibited ANDV infection of human endothelial cells irrespective of the N39D mutation. In contrast, the Syrian hamster wild-type β3 PSI domain had no effect on NY-1V infection of endothelial cells, whereas the Syrian hamster N39D mutant blocked NY-1V infectivity similar to the human β3 PSI domain. This supports previous findings on the specificity of NY-1V interactions with β3 (38) and indicates that ANDV interactions with β3 integrins require discrete PSI domain residues from that of NY-1V.

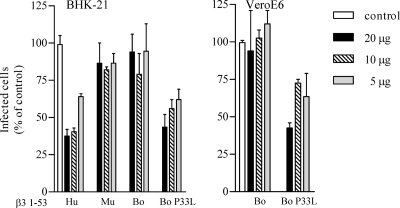

Specific PSI domain inhibition of ANDV infection further suggested that PSI domain sequences determine ANDV attachment and infectivity. We previously determined that substituting residues 1 to 43 of murine β3 with human β3 sequences conferred hantavirus infection (38). When this finding is considered, only two residues in the murine β3 (T30 and S32) and one in the bovine β3 (P33) are completely discrete from human or Syrian hamster PSI domain sequences (Fig. 6). Murine and bovine β3 PSI domains contain unique proline changes in adjacent residues (32 and 33, Fig. 6 [boxed]) that differ from the Syrian hamster and human β3 PSI domains and suggest that they are determinants of ANDV binding to β3 integrins.

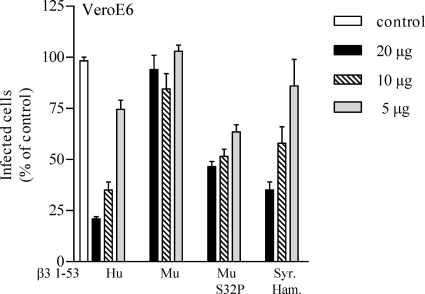

In order to define the role of proline 33 in ANDV recognition, we mutated the bovine β3 integrin proline 33 to the leucine (P33L) present in human homologues and then determined whether the bovine P33L PSI domain mutant was capable of inhibiting ANDV infection. We similarly mutated the murine β3 PSI domain to contain a proline residue at position 32 (S32P) in order to mimic the human β3 PSI domain. Figure 8 indicates that the murine β3 PSI domain fails to inhibit ANDV infectivity, whereas both human and Syrian hamster β3 PSI domains block ANDV infection. However, the murine S32P mutant β3 PSI domain also inhibited ANDV infection by >50%. Similar to murine β3, the wild-type bovine β3 PSI domain failed to inhibit ANDV infection of BHK-21 cells and VeroE6 cells (Fig. 9). However, the P33L mutant bovine β3 PSI domain inhibited ANDV infection of VeroE6 and BHK-21 cells by 60 and 55%, respectively. These findings suggest that the absence of proline 32 or the addition of a second proline at position 33 in the β3 integrin PSI domain dramatically reduces ANDV recognition of PSI domain polypeptides.

FIG. 8.

Murine β3 integrin PSI domain mutants inhibit ANDV infection. Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg) of human, murine, murine S32P, and Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domains were incubated with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV for 2 h at 4°C. Mixtures were adsorbed to VeroE6 cells in a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. After a washing step, the cells were incubated for 24 h, and the number of ANDV-infected cells was quantitated by immunoperoxidase staining of the nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the mock-treated controls.

FIG. 9.

P33L Mutants of the bovine β3 integrin inhibit ANDV infection. Increasing amounts (5 to 20 μg) of human, murine, bovine (Bo) wild-type, or bovine P33L β3 integrin PSI domain were incubated with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV for 2 h at 4°C. Mixtures were adsorbed onto BHK-21 or VeroE6 cells in a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. After a washing step, the cells were incubated for 24 h, and the number of ANDV-infected cells was quantitated by immunoperoxidase staining of the nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as a percentage of the mock-treated controls.

To further evaluate the effect of P33 on ANDV infection, we reciprocally mutated the full-length bovine β3 subunit to contain P33L and the full-length human β3 to contain L33P. Subsequently, we transfected CHO cells with the β3 mutants and determined the susceptibility of CHO cells expressing mutant β3 subunits to ANDV infection. Equal expression of the αvβ3 integrins on the surface of CHO cells was confirmed by flow cytometry, as measured by comparable geometric mean titers of αvβ3 cell surface fluorescence. CHO cells expressing either bovine β3 or the human β3 L33P mutant failed to confer ANDV infectivity (Fig. 10). In contrast, CHO cells expressing either human αvβ3 or a bovine β3 P33L mutant enhanced ANDV infection by >5-fold (Fig. 10). These results establish that a proline residue at position 33 inhibits ANDV recognition of β3 integrin PSI domains and further demonstrate the β3 integrin sequence specificity of ANDV recognition.

FIG. 10.

Bovine β3 integrin P33L confers cell susceptibility to ANDV infection. CHO cells were cotransfected with recombinant human αv integrin subunits along with human wild-type β3, bovine wild-type β3, mutant bovine P33L β3, or human L33P β3 integrin subunits. Cell surface expression of αvβ3 integrins was determined by flow cytometry, and cells were subsequently infected with ∼1,000 FFU of ANDV for 1 h at 37°C. After viral adsorption, inocula were removed, and the cells were washed and incubated 24 h at 37°C before fixation. Infected CHO cells were quantitated by immunoperoxidase staining of the nucleocapsid protein as previously described (38). The results were reproduced in at least two separate experiments and are presented as fold of mock-transfected controls.

DISCUSSION

β3 integrins are prominent cell surface receptors on endothelial cells and regulate vascular integrity, permeability, and hemostasis (2, 6, 19, 23, 39, 40). Interestingly, all pathogenic hantaviruses analyzed thus far use β3 integrin receptors on human endothelial cells and cause vascular permeability-based diseases (HTNV, SNV, Puumala virus [PUUV], Seoul virus [SEOV], and NY-1V), whereas α5β1 integrins are used by nonpathogenic hantaviruses (13, 16, 38). ANDV infection of Syrian hamsters is a model of HPS pathogenesis that closely mimics human disease (20, 21, 50); however, the use of β3 integrins by ANDV has not been established. We performed here a series of experiments to determine how ANDV interacts with β3 integrins. Our results indicate that ANDV infection of either human endothelial cells or Syrian hamster BHK-21 cells was inhibited by the high-affinity αvβ3 integrin ligand vitronectin and antibodies against β3 subunits. These findings demonstrate that ANDV infectivity is dependent on the presence of β3 integrins.

β3 integrins reportedly form at least two conformations: an active extended conformation which binds vitronectin and an inactive bent conformation which forms the basal integrin state (30, 53, 55). Pathogenic hantaviruses have been shown to bind PSI domains present at the apex of bent inactive β3 integrin subunits, and the binding is species specific (38). The results presented here demonstrate that antibodies against the β3 integrin PSI domain, as well as PSI domain polypeptides derived from either human or Syrian hamster origin, inhibit ANDV infectivity. In contrast, ANDV failed to recognize PSI domain polypeptides of murine or bovine origin. These findings indicate that ANDV selectively recognizes human and Syrian hamster β3 integrin PSI domains which direct ANDV infectivity. These findings are consistent with ANDV pathogenesis in both humans and Syrian hamsters.

The species-specific use of β3 integrin PSI domains permitted us to further analyze critical residues within the PSI domain required for ANDV recognition. A comparison of species specific β3 subunit PSI domains shows that murine and bovine β3 sequences contain proline substitutions at positions 32 and 33 (P32S and L33P, respectively) resulting in the absence of proline (murine) or the presence of two adjacent prolines (bovine) in this domain. Mutagenesis demonstrated that ANDV recognition of human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins is abolished by substituting leucine for proline at position 33 of the human β3 subunit (L33P). Similarly, substituting proline for serine (P32S) in the murine β3 PSI domain permitted the PSI domain to function as an inhibitor of ANDV infection. Conversely, when proline 33 of the bovine β3 subunit was replaced by leucine (P33L) the mutant bovine β3 subunit also conferred cell susceptibility to ANDV infection. These findings indicate that ANDV specificity for β3 integrins is directed by residues 32 and 33 or altered by proline-induced changes at these positions. Interestingly, required β3 residues for ANDV binding differ from recognition sequences of NY-1V. In contrast to ANDV, NY-1V binding to β3 is dependent on D39, blocked by introducing N39 within human β3 (38) or the N39 containing wild-type Syrian hamster β3 (Fig. 7), and unaltered by residue 32 or 33 substitutions (38). This is a fundamental difference in β3 recognition between ANDV and NY-1V; however, residues required for binding of either virus reside within the same β3 domain. These findings suggest that additional pathogenic hantaviruses may also have unique β3 residue binding requirements that specify their integrin interactions.

It is unclear whether unique ANDV interactions with β3 integrins are responsible for the discrete ability of ANDV to cause disease in Syrian hamsters or permit person to person transmission. NY-1V is clearly restricted in BHK-21 Syrian hamster cells (Fig. 1), and the data presented here suggest that at one level this difference may be due to species-specific β3 integrin residues (Fig. 7B). It is unclear whether similar differences in β3 residue requirements will be observed in SNV and HTNV, which are also nonpathogenic in Syrian hamsters and yet pathogenic in humans. However, there are many reasons for why a virus may be restricted from causing disease in another species. In fact, analysis of an SNV reassortant containing the ANDV M segment, and its encoded attachment proteins, indicates that SNV is restricted from causing disease in Syrian hamsters as a result of its S and L segments (33). In fact, S and L segment RNA transcription by the SAS reassortant is identical to SNV and reduced 1 to 2 logs from that of ANDV (33), suggesting that replication differences may restrict SNV from being pathogenic in Syrian hamsters. Consistent with this, SNV did not cause viremia within infected Syrian hamsters, and no S-segment RNA was isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells after infection (50). However, it is also possible that SNV and ANDV differ in their ability to regulate other cell or immune response imposed restrictions within Syrian hamsters that both viruses regulate successfully in order to be pathogenic in humans. Although there are many hurdles for a virus to overcome in order to be pathogenic in any species, the use of human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins by ANDV and the function of β3 integrins in regulating vascular permeability provide a compelling role for the involvement of β3 in the hantavirus disease process.

The importance of residues 32 and 33 as determinants of β3 integrin antigenic specificity furthers the potential role of β3 in altering vascular barrier functions during hantavirus infection. The L33P substitution is a naturally occurring β3 integrin polymorphism that differentiates human platelet antigen 1a (HPA-1a) from HPA-1b (24, 51). Interestingly, the L33P substitution is sufficient to direct autoimmune responses to β3 integrins from blood containing a different HPA type, and this immune response to β3 results in two autoimmune diseases, fetomaternal allo-immune thrombocytopenia (FMAIT) and posttransfusion purpura (PTP) (24, 49, 51). FMAIT and PTP patients display vascular permeability and acute thrombocytopenia similar to symptoms of hantavirus-infected HFRS and HPS patients (24, 49, 51). Unfortunately, there are no patient data available on the role of the HPA-1a/1b polymorphism on hantavirus infection or disease. One study has indicated that a polymorphism in the HPA-3b allele (I843S) of αIIbβ3 integrins results in more severe clinical HFRS disease (29). However, since only 1% of the Asian population is homozygous for the HPA-1b allele, the study did not determine whether HPA-1 influences hantavirus disease (43).

Thrombocytopenia is another hallmark of patients infected by pathogenic hantaviruses (8, 36, 41, 54); however, neither the role of platelets in hantavirus disease nor the mechanism of hantavirus induced thrombocytopenia has been defined (31, 41). Cosgriff et al. demonstrated that platelets from HFRS patients are defective in platelet activation (aggregation and granule release) and that this defect was not the result of a soluble circulating factor (7). This implies that thrombocytopenia in HFRS patients results from a block in platelet activation rather than from excessive platelet activation. This platelet defect following hantavirus infection, together with an understanding of hantavirus binding to inactive αIIbβ3 integrins, suggests that hantaviruses may bind inactive αIIbβ3 integrin conformers and prevent platelet activation. Since hantaviruses are cell associated at late times after infection (17), this also suggests that cell surface-displayed hantaviruses could potentially recruit quiescent platelets to the endothelial cell surface and simultaneously prevent platelet activation, reduce the level of activated platelets, and mask the presence of hantavirus-infected cells.

Our findings do not exclude additional immunologic mechanisms which may contribute to hantavirus pathogenesis and vascular permeability (25-28, 32, 34, 44, 46). However, these and other findings suggest that there are a number of means by which hantavirus dysregulation of β3 integrin functions may contribute to vascular permeability and pathogenesis (6, 13-16, 31, 38-40). Pathogenic hantaviruses clearly alter the permeability of infected endothelial cells in a manner consistent with the effects of β3 integrin dysregulation (2, 3, 6, 14, 15, 23, 38-40). Pathogenic hantaviruses selectively inhibit β3 integrin-directed migration (15) and enhance endothelial cell permeability in response to VEGF (14). However, hantavirus regulation of endothelial cell integrin functions is not the result of virus adsorption, since low MOIs (0.1 to 1) are applied to cells, and neither endothelial cell migration nor endothelial cell permeability are altered at early times after infection (14, 15). Inhibited migration and enhanced permeability of endothelial cells is only observed days after infection (14, 15) when hantaviruses reportedly coat the surface of infected cells (17). In fact, pathogenic hantaviruses may remain cell associated through hantavirus-β3 interactions on the surfaces of endothelial cells and thus contribute to β3 dysfunction and enhanced endothelial cell permeability following viral emergence. These findings further suggest that ANDV interactions with β3 integrins could contribute to endothelial cell barrier dysfunction observed in humans and Syrian hamsters after ANDV infection. The studies presented here rationalize the use of the ANDV Syrian hamster HPS disease model to determine whether β3 integrins contribute to hantavirus pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Hjelle at the University of New Mexico for generously providing ANDV for these studies. We thank Timothy Pepini for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI47873, PO1AI055621, and U54AI57158 (Northeast Biodefense Center [director, W. I. Lipkin]) and by a Veterans Affairs Merit Award to E.R.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, E. K., E. C. Tozer, M. Pfaff, S. J. Shattil, J. C. Loftus, and M. H. Ginsberg. 1997. A genetic analysis of integrin function: Glanzmann thrombasthenia in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1973-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges, E., Y. Jan, and E. Ruoslahti. 2000. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 bind to the β3 integrin through its extracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39867-39873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brakenhielm, E. 2007. Substrate matters: reciprocally stimulatory integrin and VEGF signaling in endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 101:536-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, J. P., and T. M. Cosgriff. 2000. Hemorrhagic fever virus-induced changes in hemostasis and vascular biology. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 11:461-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coller, B. 1997. GPIIb/IIIa antagonists: pathophysiologic and therapeutic insights from studies of c7E3 Fab. Thromb. Haemost. 78:730-735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coller, B. S., and S. J. Shattil. 2008. The GPIIb/IIIa (integrin αIIbβ3) odyssey: a technology-driven saga of a receptor with twists, turns, and even a bend. Blood 112:3011-3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosgriff, T. M., H. W. Lee, A. F. See, D. B. Parrish, J. S. Moon, D. J. Kim, and R. M. Lewis. 1991. Platelet dysfunction contributes to the haemostatic defect in haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 85:660-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosgriff, T. M., and R. M. Lewis. 1991. Mechanisms of disease in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Kidney Int. Suppl. 35:S72-S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denisova, E., W. Dowling, R. LaMonica, R. Shaw, S. Scarlata, F. Ruggeri, and E. R. Mackow. 1999. Rotavirus capsid protein VP5* permeabilizes membranes. J. Virol. 73:3147-3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dvorak, H. F., T. M. Sioussat, L. F. Brown, B. Berse, J. A. Nagy, A. Sotrel, E. J. Manseau, L. Van de Water, and D. R. Senger. 1991. Distribution of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) in tumors: concentration in tumor blood vessels. J. Exp. Med. 174:1275-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enria, D., P. Padula, E. L. Segura, N. Pini, A. Edelstein, C. R. Posse, and M. C. Weissenbacher. 1996. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Argentina: possibility of person to person transmission. Medicina 56:709-711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galeno, H., J. Mora, E. Villagra, J. Fernandez, J. Hernandez, G. J. Mertz, and E. Ramirez. 2002. First human isolate of hantavirus (Andes virus) in the Americas. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:657-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., E. J. Brown, M. H. Ginsberg, and E. R. Mackow. 1999. Cellular entry of hantaviruses which cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is mediated by β3 integrins. J. Virol. 73:3951-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., E. E. Gorbunova, N. A. Mackow, and E. R. Mackow. 2008. Hantaviruses direct endothelial cell permeability by sensitizing cells to the vascular permeability factor VEGF, while angiopoietin 1 and sphingosine 1-phosphate inhibit hantavirus-directed permeability. J. Virol. 82:5797-5806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., T. Peresleni, E. Geimonen, and E. R. Mackow. 2002. Pathogenic hantaviruses selectively inhibit beta3 integrin directed endothelial cell migration. Arch. Virol. 147:1913-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., M. Shepley, R. Shaw, M. H. Ginsberg, and E. R. Mackow. 1998. β3 integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7074-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith, C. S., L. H. Elliott, C. J. Peters, and S. R. Zaki. 1995. Ultrastructural characteristics of Sin Nombre virus, causative agent of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Arch. Virol. 140:2107-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayasaka, D., K. Maeda, F. A. Ennis, and M. Terajima. 2007. Increased permeability of human endothelial cell line EA.hy926 induced by hantavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Virus Res. 123:120-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodivala-Dilke, K. M., K. P. McHugh, D. A. Tsakiris, H. Rayburn, D. Crowley, M. Ullman-Cullere, F. P. Ross, B. S. Coller, S. Teitelbaum, and R. O. Hynes. 1999. β3-Integrin-deficient mice are a model for Glanzmann thrombasthenia showing placental defects and reduced survival. J. Clin. Investig. 103:229-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper, J. W., A. M. Ferro, and V. Wahl-Jensen. 2008. Immune serum produced by DNA vaccination protects hamsters against lethal respiratory challenge with Andes virus. J. Virol. 82:1332-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hooper, J. W., T. Larsen, D. M. Custer, and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. A lethal disease model for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology 289:6-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hynes, R. O. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hynes, R. O., and K. M. Hodivala-Dilke. 1999. Insights and questions arising from studies of a mouse model of Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Thromb. Haemost. 82:481-485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joutsi-Korhonen, L., S. Preston, P. A. Smethurst, M. Ijsseldijk, E. Schaffner-Reckinger, K. L. Armour, N. A. Watkins, M. R. Clark, P. G. de Groot, R. W. Farndale, W. H. Ouwehand, and L. M. Williamson. 2004. The effect of recombinant IgG antibodies against the leucine-33 form of the platelet β3 integrin (HPA-1a) on platelet function. Thromb. Haemost. 91:743-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khaiboullina, S. F., A. A. Rizvanov, V. M. Deyde, and S. C. St Jeor. 2005. Andes virus stimulates interferon-inducible MxA protein expression in endothelial cells. J. Med. Virol. 75:267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilpatrick, E. D., M. Terajima, F. T. Koster, M. D. Catalina, J. Cruz, and F. A. Ennis. 2004. Role of specific CD8+ T cells in the severity of a fulminant zoonotic viral hemorrhagic fever, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J. Immunol. 172:3297-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krakauer, T., J. W. Leduc, and H. Krakauer. 1995. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Viral Immunol. 8:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linderholm, M., C. Ahlm, B. Settergren, A. Waage, and A. Tarnvik. 1996. Elevated plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, soluble TNF receptors, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-10 in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 173:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, Z., M. Gao, Q. Han, S. Lou, and J. Fang. 2009. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (HPA-1 and HPA-3) polymorphisms in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Hum. Immunol. 70:452-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo, B. H., J. Takagi, and T. A. Springer. 2003. Locking the β3 integrin I-like domain into high and low affinity conformations with disulfides. J. Biol. Chem. 279:10215-10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackow, E. R., and I. N. Gavrilovskaya. 2001. Cellular receptors and hantavirus pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:91-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maes, P., J. Clement, P. H. Groeneveld, P. Colson, T. W. Huizinga, and M. Van Ranst. 2006. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha genetic predisposing factors can influence clinical severity in nephropathia epidemica. Viral Immunol. 19:558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McElroy, A. K., J. M. Smith, J. W. Hooper, and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2004. Andes virus M genome segment is not sufficient to confer the virulence associated with Andes virus in Syrian hamsters. Virology 326:130-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori, M., A. L. Rothman, I. Kurane, J. M. Montoya, K. B. Nolte, J. E. Norman, D. C. Waite, F. T. Koster, and F. A. Ennis. 1999. High levels of cytokine-producing cells in the lung tissues of patients with fatal hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 179:295-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niikura, M., A. Maeda, T. Ikegami, M. Saijo, I. Kurane, and S. Morikawa. 2004. Modification of endothelial cell functions by Hantaan virus infection: prolonged hyper-permeability induced by TNF-alpha of Hantaan virus-infected endothelial cell monolayers. Arch. Virol. 149:1279-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolte, K. B., R. M. Feddersen, K. Foucar, S. R. Zaki, F. T. Koster, D. Madar, T. L. Merlin, P. J. McFeeley, E. T. Umland, and R. E. Zumwalt. 1995. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the United States: a pathological description of a disease caused by a new agent. Hum. Pathol. 26:110-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Padula, P. J., A. Edelstein, S. D. Miguel, N. M. Lopez, C. M. Rossi, and R. D. Rabinovich. 1998. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome outbreak in Argentina: molecular evidence for person-to-person transmission of Andes virus. Virology 241:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raymond, T., E. Gorbunova, I. N. Gavrilovskaya, and E. R. Mackow. 2005. Pathogenic hantaviruses bind plexin-semaphorin-integrin domains present at the apex of inactive, bent αvβ3 integrin conformers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:1163-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds, L. E., L. Wyder, J. C. Lively, D. Taverna, S. D. Robinson, X. Huang, D. Sheppard, R. O. Hynes, and K. M. Hodivala-Dilke. 2002. Enhanced pathological angiogenesis in mice lacking β3 integrin or β3 and β5 integrins. Nat. Med. 8:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson, S. D., L. E. Reynolds, L. Wyder, D. J. Hicklin, and K. M. Hodivala-Dilke. 2004. β3-Integrin regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-A-dependent permeability. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24:2108-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmaljohn, C., and B. Hjelle. 1997. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmaljohn, C. S. 2001. Bunyaviridae and their replication, p. 1581-1602. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA.

- 43.Sun, G. D., X. M. Duan, Y. P. Zhang, Z. Z. Yin, X. L. Niu, Y. F. Li, H. J. Niu, and Y. L. Zhao. 2005. Analysis of genetic polymorphism in randomized donor's HPA 1-16 antigens and establishment of typed platelet donor data bank. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 13:889-895. (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sundstrom, J. B., L. K. McMullan, C. F. Spiropoulou, W. C. Hooper, A. A. Ansari, C. J. Peters, and P. E. Rollin. 2001. Hantavirus infection induces the expression of RANTES and IP-10 without causing increased permeability in human lung microvascular endothelial cells. J. Virol. 75:6070-6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor, S. L., N. Frias-Staheli, A. Garcia-Sastre, and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2009. Hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein binds to importin alpha proteins and inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced activation of nuclear factor κB. J. Virol. 83:1271-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Temonen, M., J. Mustonen, H. Helin, A. Pasternack, A. Vaheri, and H. Holthofer. 1996. Cytokines, adhesion molecules, and cellular infiltration in nephropathia epidemica kidneys: an immunohistochemical study. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 78:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toro, J., J. D. Vega, A. S. Khan, J. N. Mills, P. Padula, W. Terry, Z. Yadon, R. Valderrama, B. A. Ellis, C. Pavletic, R. Cerda, S. Zaki, W. J. Shieh, R. Meyer, M. Tapia, C. Mansilla, M. Baro, J. A. Vergara, M. Concha, G. Calderon, D. Enria, C. J. Peters, and T. G. Ksiazek. 1998. An outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Chile, 1997. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:687-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuvim, M. J., S. E. Evans, C. G. Clement, B. F. Dickey, and B. E. Gilbert. 2009. Augmented lung inflammation protects against influenza A pneumonia. PLoS ONE 4:e4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Gils, J. M., J. Stutterheim, T. J. van Duijn, J. J. Zwaginga, L. Porcelijn, M. de Haas, and P. L. Hordijk. 2009. HPA-1a alloantibodies reduce endothelial cell spreading and monolayer integrity. Mol. Immunol. 46:406-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahl-Jensen, V., J. Chapman, L. Asher, R. Fisher, M. Zimmerman, T. Larsen, and J. W. Hooper. 2007. Temporal analysis of Andes virus and Sin Nombre virus infections of Syrian hamsters. J. Virol. 81:7449-7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watkins, N. A., P. A. Smethurst, D. Allen, G. A. Smith, and W. H. Ouwehand. 2002. Platelet alphaIIbbeta3 recombinant autoantibodies from the B-cell repertoire of a posttransfusion purpura patient. Br. J. Hematol 116:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells, R. M., S. Sosa Estani, Z. E. Yadon, D. Enria, P. Padula, N. Pini, J. N. Mills, C. J. Peters, and E. L. Segura. 1997. An unusual hantavirus outbreak in southern Argentina: person-to-person transmission? Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:171-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao, T., J. Takagi, B. S. Coller, J. H. Wang, and T. A. Springer. 2004. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature 432:59-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaki, S., P. Greer, L. Coffield, C. Goldsmith, K. Nolte, K. Foucar, R. Feddersen, R. Zumwalt, G. Miller, P. Rollin, T. Ksiazek, S. Nichol, and C. Peters. 1995. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: pathogenesis of an emerging infectious disease. Am. J. Pathol. 146:552-579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu, J., B. H. Luo, T. Xiao, C. Zhang, N. Nishida, and T. A. Springer. 2008. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol. Cell 32:849-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]