Abstract

Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection causes diarrhea, which is often bloody and which can result in potentially life-threatening hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). Urtoxazumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the Shiga-like toxin 2 (Stx2) produced by STEC, has been developed as a promising agent for the prevention of HUS. Single randomized, intravenous, double-blind, placebo-controlled doses of urtoxazumab were administered to assess its safety and pharmacokinetics in healthy adults (0.1 to 3.0 mg/kg of body weight) and STEC-infected pediatric patients (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg). No dose-related safety trends were noted, nor were antiurtoxazumab antibodies detected. The disposition of urtoxazumab showed a biexponential decline, regardless of the dose. In healthy adults, the mean terminal elimination half-life was consistent across the dose groups and ranged from 24.6 days (3.0-mg/kg dose group) to 28.9 days (0.3-mg/kg dose group). The mean maximum serum drug concentration (Cmax) ranged from 2.6 μg/ml at 0.1 mg/kg to 71.7 μg/ml at 3.0 mg/kg. The disposition of urtoxazumab following the administration of doses of 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg in pediatric patients showed mean Cmaxs of 19.6 and 56.1 μg/ml, respectively. Urtoxazumab was well tolerated, appears to be safe at doses of up to 3.0 mg/kg, and is a potential candidate for the prevention of HUS in pediatric patients.

Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are major pathogens in humans, and STEC infections have been associated with severe complications, such as bloody diarrhea (BD) and hemorrhagic colitis. In 1.6 to 15% of STEC infections, serious morbidity and mortality due to the development of hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) may occur (2, 7, 10, 11, 19, 21). HUS is a serious and life-threatening condition characterized by acute renal impairment, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia (2, 7, 21) and is the leading cause of acute renal failure in children (21). The utility of antibiotic therapy is controversial, and an effective treatment that would reduce the incidence or the severity of HUS is not available (7). At present, there are no specific protective measures against STEC infection, and supportive therapy is the only treatment option available.

Escherichia coli O157:H7, first identified in 1982 as a human pathogen spread by contaminated beef (4), has more recently been associated with vegetable (18) and milk (3) contamination, as well as additional beef contaminations (1, 22). Non-O157 STEC strains have also been associated with the development of HUS (12). Strains of STEC (both O157 and non-O157 strains) may produce Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and/or Shiga-like toxin 2 (Stx2) and are associated with STEC infection and medical complications. Stx2 appears to be approximately 400-fold more toxic in mice than Stx1 (20). The Stx2 genotype is the most prevalent genotype identified in STEC isolates recovered from patients with HUS (6, 15).

Urtoxazumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody (MAb) of IgG subclass IgG1 against the B subunit of Stx2, has been developed (8). It has been shown to neutralize Stx2 in vitro and to completely prevent mortality in animal models of severe STEC infection (23) and Stx2 toxin inoculation (9). We recently conducted two studies designed to examine the safety and pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of urtoxazumab in healthy adults and STEC-infected pediatric patients. The phase 1 study with healthy adults was a first-in-human, dose-escalation, single-dose safety trial. Following its completion, a randomized placebo-controlled study with STEC-infected pediatric patients (sequential dose escalation, followed by parallel group treatment) was conducted. Here we report on the safety and PK results obtained during the course of these studies.

(Parts of this study were presented at the 44th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington, DC, 30 October to 2 November 2004, and the 46th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, CA, 27 to 30 September 2006.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study approvals.

The studies were approved by the U.S., Canadian, and Argentinean regulatory agencies and by local institutional review boards or ethical review committees. The studies were also conducted in compliance with the regulations of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study participants or their legal representatives provided written, informed consent prior to study entry.

Study with healthy adults. (i) Study design.

The eligibility criteria for subjects of either gender who were between 19 and 65 years of age were as follows: they were free of clinically relevant cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, hematological, neurological, infectious, and psychiatric disease, as determined from the medical history, a physical examination, and laboratory tests; they were within ±20% of their ideal body weight for their height and body frame; they had no history of exposure to murine or human MAbs; they had no less than 50% of the lower limit of normal for IgG and IgA levels; and they were not currently using prescription or over-the-counter drugs. In addition, the female participants could not be pregnant or nursing and had to be using an approved form of contraception, if appropriate.

(ii) Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of urtoxazumab.

The safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of urtoxazumab were evaluated in subjects who were randomly assigned to receive a single 100-ml intravenous (i.v.) infusion of urtoxazumab over the course of 30 min at one of four dosage levels (0.1, 0.3, 1.0, or 3.0 mg/kg of body weight) or placebo. Eight subjects in each cohort were stratified in a 3:1 ratio of active drug to placebo. Serum samples for PK analyses were processed at scheduled time points, as described below. Safety was assessed by using the findings of pre- and posttreatment electrocardiographs (ECG), physical examinations, vital signs, clinical chemistry, hematology, urinalysis, antiurtoxazumab antibody assessments, and adverse event (AE) reporting. A 7-day safety evaluation and review period was completed for each cohort prior to the subsequent dose escalation. Samples for PK analysis were batched and analyzed in a central laboratory (MDS Pharma Services, St. Laurent, Quebec, Canada) by a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Study with STEC-infected pediatric patients. (i) Study design.

Children of both genders were considered eligible for this study if they were 1 to 15 years of age; had had bloody diarrhea for ≤72 h at the time of study drug administration; and were positive for STEC infection, as determined by assessing a stool sample by the use of diagnostic test kits (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) and/or a PCR assay (see “Diagnosis of STEC infection” below); did not have two or more symptoms indicative of the early stages of HUS (hemolytic anemia, red blood cell [RBC] fragmentation, decreased platelet count, advanced hematuria, or highly elevated serum creatinine levels); were not anuric or oliguric; had no evidence of clinically significant gastrointestinal disease; had no history of anemia, renal disease, thrombocytopenia, inflammatory bowel disease, or immunodeficiency; were not severely dehydrated; had no medical history of exposure to murine or human MAbs; and were not administered antibiotics or antimotility or laxative drugs. The female participants could not be pregnant or nursing and had to be using approved contraceptives, if appropriate.

(ii) Diagnosis of STEC infection.

The diagnosis of STEC infection in pediatric patients was determined by using the following procedures. (i) Raw and cultured stool samples from pediatric patients were analyzed for the presence of E. coli O157 by using the commercially available Immuno Card STAT! E. coli O157 Plus immunoassay (Meridian Bioscience, Inc.). (ii) Raw and cultured stool samples were assayed by using the Premier enterohemorrhagic E. coli immunoassay (Meridian Bioscience, Inc.) to determine the presence or absence of Stx1 and/or Stx2. (iii) Raw stool samples were cultured on sorbitol-MacConkey (SMAC) agar plates, and E. coli colonies were isolated to confirm the presence of Stx2 by a well-established PCR method (13, 19, 20) conducted in a central laboratory (Hospital de Niños Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

The study was conducted in two parts. In the first part, STEC-infected pediatric patients were sequentially enrolled in double-blind randomized fashion into one of two cohorts of 12 patients each. The patients in the first cohort were stratified to receive an i.v. infusion of either placebo or 1.0 mg/kg urtoxazumab (1:2 ratio) in a total volume of 10 ml/kg for those with body weights of <10 kg or up to a maximum infusion volume of 100 ml for those with body weights of ≥10 kg. The infusion was administered over a period of 1 h. Similarly, the patients in the second cohort received an i.v. infusion of either placebo or 3.0 mg/kg urtoxazumab (1:2 ratio), following a thorough independent and blind safety evaluation of the data for the first cohort. The decision to expand the study to an additional 85 STEC-infected pediatric patients using a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group design with 1.0- and 3.0-mg/kg urtoxazumab doses was determined on the basis of an independent safety analysis of the data for the initial 24 patients, after confirmation of the absence of any safety concerns. Safety was assessed during drug infusion and posttreatment follow-up on the first day (up to 8 h following the infusion); on days 2, 4, 6, 8, 22, and 57; and at month 4. The bases for the determination of safety were the findings from analyses of data from the pre- and posttreatment physical examinations; vital signs; the concomitant medications taken; clinical chemistry, hematology, urinalysis, antiurtoxazumab antibody level, and plasma and urine thrombomodulin level results; the urtoxazumab PK parameters; and the AEs.

Measurement of urtoxazumab and antiurtoxazumab antibodies. (i) Pharmacokinetic analyses.

For the healthy adults, blood samples for PK analyses were drawn at the baseline; 5 min after the completion of the infusion; 1, 4, and 8 h postdosing; and days 2, 5, 8, 15, 22, 36, and 57. For the pediatric patients, blood samples for PK analyses were drawn at the baseline, 5 min, and 4 to 8 h; days 2, 4, 8, 22, and 57; and month 4 after the completion of the infusion. Serum samples were stored at −70°C until they were analyzed for their drug concentrations. An ELISA method for the determination of urtoxazumab levels in serum was developed by the use of the guiding principles of a published bioanalytical method validation (16). The calibration range (0.3 to 4.0 μg/ml), accuracy (86.1 to 93.5%), precision (within 9.7%), selectivity dilution linearity (up to about 116,000 times), and stability (5 h at room temperature and 420 days at −80°C) were confirmed. Serum samples containing urtoxazumab were batched and analyzed by this validated ELISA in a central laboratory (MDS Pharma Services). All samples were analyzed within the validated storage stability period. Serum urtoxazumab concentrations were summarized by time point and treatment by the use of descriptive statistics. The following pharmacokinetic parameters for urtoxazumab in serum were determined by noncompartmental analysis, where appropriate, from the individual serum concentration-time profiles (by use of the WinNonlin Professional program for the study with healthy adults and the SAS program [version 6.12/8] for the study with STEC-infected pediatric patients): maximum serum drug concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (Tmax), serum half-life (t1/2), and area under the curve from the start of infusion to infinity (AUC0-∞). The estimated values of the parameters were summarized with descriptive statistics by treatment.

(ii) Antiurtoxazumab antibody analyses.

Blood samples for analysis of the antiurtoxazumab antibody titers were obtained from healthy adults at the baseline and days 22 and 57 posttreatment and from the pediatric patients at the baseline, days 22 and 57, and month 4 posttreatment. Serum was separated from the blood, and the samples were batched and analyzed in a central laboratory (MDS Pharma Services) by a validated ELISA for the detection of antiurtoxazumab antibodies. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of serum antiurtoxazumab antibodies was 1.6 μg/ml.

RESULTS

Demographics. (i) Healthy adults.

A total of 32 subjects (15 females, 17 males) were enrolled. Twenty-eight subjects were Caucasian, and one subject was listed in each of the following categories: American Indian, Asian, European/Middle Eastern, and Hispanic. The mean age of the subjects was 40 years (range, 19 to 60 years), the mean weight was 75 kg (range, 48 to 95 kg), and the mean height was 175 cm (range, 157 to 193 cm).

(ii) STEC-infected pediatric patients.

A total of 109 STEC-infected pediatric patients were enrolled in both parts of the pediatric study. The patients' demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics of STEC-infected pediatric population

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 36) | Urtoxazumab at 1 mg/kg (n = 38) | Urtoxazumab at 3 mg/kg (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD age (yr) | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 2.8 ± 2.4 |

| Gender (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| Male | 20 (55.6) | 20 (52.6) | 17 (48.6) |

| Female | 16 (44.4) | 18 (47.4) | 18 (51.4) |

| Ethnicity (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| White | 36 (100.0) | 37 (97.4) | 33 (94.3) |

| Othera | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.7) |

| Body wt (kg) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 13.7 ± 5.0 | 14.7 ± 5.4 | 14.5 ± 6.5 |

| Median | 12.1 | 13.1 | 12.5 |

| Range | 7.7 to 28.5 | 8.4 to 33.9 | 7.7 to 31.0 |

Other includes the categories Metis (n = 2) and Eurasian (n = 1).

Safety. (i) Healthy adults.

In healthy male and female adults, no dose-related trends were noted with respect to vital signs, ECG findings, clinical laboratory results, or physical examinations. Eighty AEs were reported by 22 of 32 subjects (69%). The majority of the AEs were mild in intensity and were considered to be unrelated to the study treatment. Two subjects experienced urticarial events, but these were considered by the investigators to be unrelated to the urtoxazumab treatment. One subject whose medical history reported an allergic response to sulfur-containing drugs exhibited moderate urticaria on study days 49 through 51. The second subject, whose medical history indicated allergic responses to dairy products, codeine, and erythromycin, reported mild and moderate urticaria on study days 39 through 47. Headache, the most common treatment-related AE reported, was observed in nine subjects (28%). No serious adverse events (SAEs) were noted. Serum antiurtoxazumab antibody levels were below the LLOQ in all serum samples analyzed.

(ii) STEC-infected pediatric patients.

Safety data were collected from 109 STEC-infected pediatric patients (36, 38, and 35 patients in the placebo and the 1.0- and 3.0-mg/kg urtoxazumab treatment groups, respectively). No significant urtoxazumab-associated safety concerns were identified, on the basis of the analysis of all available clinical data. The intensities and frequencies of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) are described in Table 2. TEAEs, which occurred at an incidence of at least 5%, are presented by system organ class category in Table 3. TEAEs were observed in 95 patients (87%), but only 4 patients (3.7%) reported TEAEs that were considered by the investigators to be related to the study drug. Three of these TEAEs were mild in intensity and one was moderate in intensity. The mild TEAEs were pyrexia (one patient in the 1-mg/kg dose group), headache (one patient in the 3-mg/kg dose group), and erythema (one patient in the 3-mg/kg dose group). The TEAE classified as moderate (vomiting) occurred in one patient in the placebo group. A total of 25 SAEs (10, 9, and 6 SAEs in the placebo and the 1.0- and 3.0-mg/kg groups, respectively) were observed in 18 patients, and only 4 SAEs were considered by the investigators to be remotely related to the study drug. The SAEs included hypokalemia, intussusception, and HUS in the 1.0-mg/kg group and HUS in the placebo group. One death occurred in the placebo group, while another death occurred in the 1.0-mg/kg group. Neither event was considered by the investigators to be related to the study drug. The death in the 1.0-mg/kg treatment group was determined to be caused by a Klebsiella pneumoniae infection, while the death in the placebo treatment group was determined to be caused by the progression of STEC infection. Serum antiurtoxazumab antibody values were below the LLOQ in all serum samples analyzed.

TABLE 2.

Intensity and frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events in STEC-infected pediatric patients

| Intensity | No. (%) of patients reporting TEAEs by treatment group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 36) | Urtoxazumab at 1 mg/kg (n = 38) | Urtoxazumab at 3 mg/kg (n = 35) | Total (n = 109) | |

| Mild | 20 (55.6) | 20 (52.6) | 20 (57.1) | 60 (55.0) |

| Moderate | 10 (27.8) | 10 (26.3) | 9 (25.7) | 29 (26.6) |

| Severe | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 6 (5.5) |

TABLE 3.

Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (≥5%) summarized by system organ class in STEC-infected patients

| System organ class categorya | No. (%) of patients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 36) | Urtoxazumab at 1 mg/kg (n = 38) | Urtoxazumab at 3 mg/kg (n = 35) | Total (n = 109) | |

| TEAEs | 32 (88.9) | 32 (84.2) | 31 (88.6) | 95 (87.2) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 4 (11.1) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (17.1) | 16 (14.7) |

| Eye disorders | 5 (13.9) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (11.4) | 12 (11.0) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 10 (27.8) | 10 (26.3) | 12 (34.3) | 32 (29.4) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 6 (16.7) | 7 (18.4) | 5 (14.3) | 18 (16.5) |

| Infections and infestations | 20 (55.6) | 20 (52.6) | 15 (42.9) | 55 (50.4) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 6 (5.5) |

| Investigations | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.3) | 3 (8.6) | 7 (6.4) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (3.7) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1 (2.8) | 3 (7.9) | 2 (5.7) | 6 (5.5) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (2.8) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 1 (2.8) | 3 (7.9) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (4.6) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 11 (30.6) | 14 (36.8) | 14 (40.0) | 39 (35.8) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 4 (11.1) | 6 (15.8) | 9 (25.7) | 19 (17.4) |

| Vascular disorders | 6 (16.7) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (17.1) | 16 (14.7) |

The system organ class category is according to the MedDRA (version 5.1) program.

PK parameters. (i) Healthy adults.

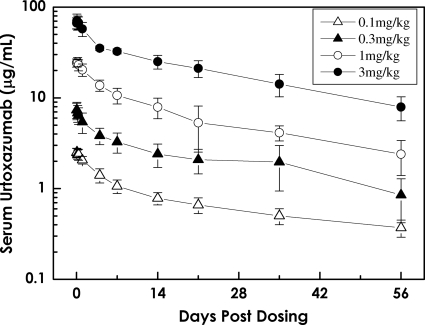

The t1/2s were 28.1 ± 10.2, 28.9 ± 9.7, 26.3 ± 5.1, and 24.6 ± 5.0 days for the 0.1-, 0.3-, 1.0-, and 3.0-mg/kg urtoxazumab treatment groups, respectively. The Cmaxs were 2.6 ± 0.3, 7.5 ± 1.5, 25.5 ± 2.4, and 71.7 ± 12.5 μg/ml for the 0.1-, 0.3-, 1.0-, and 3.0-mg/kg treatment groups, respectively. The AUC0-∞s were 50 ± 17, 168 ± 52, 480 ± 128, and 1,438 ± 287 μg·day/ml for the 0.1-, 0.3-, 1.0-, and 3.0-mg/kg treatment groups, respectively. The Cmaxs and AUC0-∞s increased in a dose-dependent manner. The mean concentrations of urtoxazumab appeared to decrease to approximately one-half of the Cmax by day 4 after dosing and to approximately one-third of the Cmax by day 14 after dosing in the four cohorts tested.

(ii) STEC-infected pediatric patients.

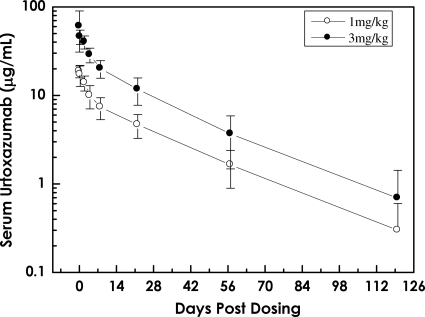

The PK profile for urtoxazumab in STEC-infected pediatric patients is summarized in Table 4. The results for the doses used with the pediatric population were compared with the results for the matched doses used with the healthy adult population. The t1/2s were 24.4 ± 6.4 and 22.4 ± 6.2 days for the 1.0- and 3.0-mg/kg urtoxazumab treatment groups, respectively. The mean Cmaxs were 19.6 ± 4.1 and 56.1 ± 12.1 μg/ml for these two groups, respectively. The disposition of urtoxazumab following an i.v. infusion appeared to follow a biexponential decline with an extended half-life, similar to the observation for healthy adults.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters generated from a single i.v. infusion of urtoxazumab in healthy adults and STEC-infected pediatric patients

| PK parameter | Healthy adults |

Pediatric patients |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mg/kg (n = 6) | 3 mg/kg (n = 6) | 1 mg/kg (n = 37) | 3 mg/kg (n = 35) | |

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 25.5 ± 2.4 | 71.7 ± 12.5 | 19.6 ± 4.1 | 56.1 ± 12.1 |

| Tmax (h) | 2.7 ± 2.0 | 3.7 ± 3.8 | 3.3 ± 4.2 | 2.9 ± 4.8 |

| AUC(0-∞) (μg·day/ml) | 480 ± 128 | 1,438 ± 287 | 342 ± 105 | 869 ± 268 |

| t1/2 (days) | 26.3 ± 5.1 | 24.6 ± 5.0 | 24.4 ± 6.4 | 22.4 ± 6.2 |

| V (ml/kg) | 76.7 ± 12.0 | 75.3 ± 13.7 | 109.4 ± 34.5 | 116.9 ± 36.8 |

DISCUSSION

We present the findings of the first studies examining the safety and PKs of a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against Stx2. The studies were preformed with healthy adults and STEC-infected pediatric patients. Since a pediatric population is the most likely group to be at a relatively higher risk of becoming ill and developing HUS, this group was considered an essential focus of a study with urtoxazumab.

In both healthy adults and STEC-infected pediatric patients, no dose-related trends were noted with respect to vital signs, clinical laboratory results, physical examinations, or TEAEs.

The serum antiurtoxazumab antibody values for all subjects at all time points were below the limit of detection, suggesting that the immunogenicity of urtoxazumab is low.

The half-lives and biexponential decline in the level of urtoxazumab following an i.v. infusion (all doses) in both healthy adults and STEC-infected pediatric patients were consistent with those reported for several approved humanized monoclonal immunoglobulins (Fig. 1 and 2) (14, 17). The t1/2s were reasonably consistent across dose groups, suggesting that the elimination of urtoxazumab is independent of the dose over the range of doses used to treat these populations. The long t1/2 also supports data from nonclinical tissue cross-reactivity studies (unpublished data), which indicated that it is unlikely that appreciable quantities of urtoxazumab bind to normal adult human tissues in vivo. The primary measures of exposure, Cmax and AUC0-∞, increased in a dose-dependent manner (Table 4). Although there was reasonable consistency in the PK data when the data obtained for similar doses were compared between the healthy adult and STEC-infected pediatric populations, slight differences in the PK profiles between the adults and the pediatric patients were observed. These expected PK differences are likely due to physiological differences between these groups known to alter the PKs of drugs, such as age, metabolism, health status, interstitial compartment size differences, and other factors (5).

FIG. 1.

Serum concentration-time curve following a single i.v. infusion of urtoxazumab (mean ± standard deviation) in healthy adult subjects.

FIG. 2.

Serum concentration-time curve following a single i.v. infusion of urtoxazumab (mean ± standard deviation) in pediatric subjects infected with STEC.

In summary, these are the first reported findings (to the best of our knowledge) describing the safety and PK profiles of a potentially therapeutic humanized monoclonal antibody against Stx2 in both healthy male and female adults and pediatric patients infected with STEC.

Urtoxazumab appears to be safe and well tolerated, and these findings support the further investigation of urtoxazumab as a potential candidate for the prevention of HUS in pediatric populations.

Acknowledgments

The generation of urtoxazumab from the parental murine monoclonal antibody and its characterization were financially supported by the Program of Fundamental Studies in Health Science of the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research of Japan (currently the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation [NIBIO]). These clinical studies were financially supported by the Program of Research and Development Promotion of Orphan Drugs, NIBIO (Japan), under orphan drug designation 153.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell, B. P., M. Goldoft, P. M. Griffin, et al. 1994. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers—the Washington experience. JAMA 272:1349-1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt, J. R., L. S. Fouser, S. L. Watkins, et al. 1994. Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome after ingestion of contaminated hamburgers. J. Pediatr. 125:519-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection associated with drinking raw milk—Washington and Oregon, Nov.-Dec. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 56:165-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1982. Epidemiologic notes and reports isolation of E. coli O157:H7 from sporadic cases of hemorrhagic colitis—United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 31:580-585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diasio, R. B. 2008. Principles of drug therapy, p. 139-150. In L. Goldman and D. Ausiello (ed.), Cecil textbook of medicine, 23rd ed. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA.

- 6.Freidrich, A. W., M. Bielaszewska, W. L. Zhang, et al. 2002. Escherichia coli harboring Shiga toxin 2 gene variants: frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J. Infect. Dis. 185:74-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan, B. S., K. E. Meyers, and S. L. Schulman. 1998. The pathogenesis and treatment of hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9:1126-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura, T., M. Sung Co, M. Vasquez, et al. 2002. Development of humanized monoclonal antibody TMA-15 which neutralizes Shiga toxin 2. Hybridoma Hybridomics 21:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura, T., S. Tani, M. Motoki, and Y. Matsumoto. 2003. Role of Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2)-binding protein, human serum amyloid P component (HuSAP), in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections: assumption from in vitro and in vivo study using HuSAP and anti-Stx2 humanized monoclonal antibody TMA-15. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305:1057-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López, E. L., M. M. Contrini, M. Sanz, et al. 1997. Perspectives on Shiga-like toxin infections in Argentina. J. Food Prot. 60:1458-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.López, E. L., M. Díaz, S. Grinstein, et al. 1989. Hemolytic uremic syndrome and diarrhea in Argentine children: the role of Shiga-like toxins. J. Infect. Dis. 160:469-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien, A. D., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: yesterday, today, and tomorrow, p. 1-12. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 13.Olsvik, O., and N. A. Strockbine. 1993. PCR detection of heat-stable, heat-labile, and Shiga-like toxin genes in Escherichia coli, p. 271-276. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, et al. (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 14.Reilley, S., E. Wenzel, L. Reynolds, et al. 2005. Open-label, dose escalation study of the safety and pharmacokinetic profile of tefibazumab in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:959-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüssmann, H., H. Schmidt, J. Heesemann, et al. 1994. Variants of Shiga-like toxin II constitute a major toxin component in Escherichia coli O157 strains from patients with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:338-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah, V. P., K. K. Midha, S. Dighe, et al. 1992. Analytical methods validation: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies. Pharm. Res. 9:588-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siva Subramanian, K. N., L. E. Weisman, T. Rhodes, et al. 1998. Safety, tolerance and pharmacokinetics of a humanized monoclonal antibody to respiratory syncytial virus in premature infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 17:110-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Söderström, A., A. Lindberg, and Y. Andersson. 2005. EHEC O157 outbreak in Sweden from locally produced lettuce, August-September. Euro. Surveill. 10:E050922.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ternhag, A., A. Törner, A. Svensson, et al. 2008. Short- and long-term effects of bacterial gastrointestinal infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:143-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tesh, V. L., J. A. Burris, J. W. Owens, et al. 1993. Comparison of the relative toxicities of Shiga-like toxins type I and type II for mice. Infect. Immun. 61:3392-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trachtman, H., and E. Christen. 1991. Pathogenesis, treatment, and therapeutic trials in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 11:162-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuttle, J., T. Gomez, M. P. Doyle, et al. 1999. Lessons from a large outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: insights into the infectious dose and method of widespread contamination of hamburger patties. Epidemiol. Infect. 122:185-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamagami, S., M. Motoki, T. Kimura, et al. 2001. Efficacy of postinfection treatment with anti-Shiga toxin (Stx) 2 humanized monoclonal antibody TMA-15 in mice lethally challenged with Stx-producing Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 184:738-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]