Abstract

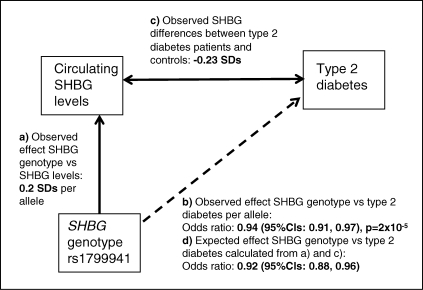

Epidemiological studies consistently show that circulating sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels are lower in type 2 diabetes patients than non-diabetic individuals, but the causal nature of this association is controversial. Genetic studies can help dissect causal directions of epidemiological associations because genotypes are much less likely to be confounded, biased or influenced by disease processes. Using this Mendelian randomization principle, we selected a common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) near the SHBG gene, rs1799941, that is strongly associated with SHBG levels. We used data from this SNP, or closely correlated SNPs, in 27 657 type 2 diabetes patients and 58 481 controls from 15 studies. We then used data from additional studies to estimate the difference in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls. The SHBG SNP rs1799941 was associated with type 2 diabetes [odds ratio (OR) 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.97; P = 2 × 10−5], with the SHBG raising allele associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. This effect was very similar to that expected (OR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.96), given the SHBG-SNP versus SHBG levels association (SHBG levels are 0.2 standard deviations higher per copy of the A allele) and the SHBG levels versus type 2 diabetes association (SHBG levels are 0.23 standard deviations lower in type 2 diabetic patients compared to controls). Results were very similar in men and women. There was no evidence that this variant is associated with diabetes-related intermediate traits, including several measures of insulin secretion and resistance. Our results, together with those from another recent genetic study, strengthen evidence that SHBG and sex hormones are involved in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

Circulating sex hormone levels are associated with type 2 diabetes, but the causal nature of these associations is controversial. Many observational epidemiological studies have described associations between type 2 diabetes and androgens (primarily testosterone), estrogens (estradiol) and their circulating binding protein, sex hormone binding protein (SHBG) (1). Meta-analyses of these studies show consistent sex-specific associations. In men, lower testosterone, higher estradiol and lower SHBG levels are associated with type 2 diabetes. In women, higher testosterone, higher estradiol and lower SHBG are associated with type 2 diabetes (1).

The differences in sex hormone levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls are complicated by increased adiposity, which is also associated with reduced SHBG. However, differences in adiposity cannot fully explain the associations between sex hormones and type 2 diabetes. In both men and women, the differences in testosterone, estradiol and SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and non-diabetic individuals remain very similar before and after controlling for BMI, age, ethnic background and, in females, menopausal status (1).

There is evidence that the associations between sex hormones and type 2 diabetes may be causal. First, a recent study described an association between two SNPs in the SHBG gene and type 2 diabetes (2). Second, prospective studies show that the levels of sex hormones are altered in individuals diagnosed many years later (1). Third, hyper-androgenic disorders such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in women result in an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and are very strongly associated with insulin resistance (3). In men, androgen supplementation in the presence of central obesity and low testosterone levels increases insulin sensitivity (4–6). Fourth, male rats lacking the androgen receptor are insulin resistant (7) and female rats treated with testosterone after oophorectomy become insulin resistant (8), findings that are consistent with the sex-specific associations seen in humans.

Despite some evidence pointing towards a causal role of sex hormones in type 2 diabetes, further evidence is required. The recent genetic study involved a relatively small number of patients (359 women and 170 men), the effect sizes, with odds ratios (ORs) of 1.52 and 1.39, are similar to those for SNPs in the TCF7L2 gene (9), which raises doubt as to why these associations were not found by genome-wide association approaches, and the evidence of association between SHBG SNPs and type 2 diabetes was not strong (P = 0.02 for each SNP under the best model) (2). It is well known that even well-conducted, well-controlled epidemiological associations can often be confounded by imperfect measurement of known, or unknown, related factors. Prospective studies establish whether or not a risk factor is present prior to disease diagnosis, but do not necessarily solve the concerns about epidemiological studies. Disease processes can start many years before disease diagnosis, which means that altered hormone levels observed prospectively could be a consequence rather than cause of early disease processes. The causal direction of the associations between hyper-androgenism and insulin resistance in PCOS is not known. Studies in animals may not be relevant to humans and human trials of androgen therapy have focused on people with extreme levels of obesity or circulating hormones and conflicting results have been reported (10,11). Finally, insulin lowering interventions in non-diabetic men and women (without PCOS) lead to increased SHBG levels, suggesting that insulin can causally influence sex hormone dynamics (12,13).

Genetic studies can be a valuable additional tool which help to dissect causal directions of epidemiological associations (14). In most situations, alleles at genetic variants are randomly distributed between individuals who differ by conventional confounding factors. This ‘Mendelian randomization’ principle has been used recently in the context of metabolic traits to provide evidence that lifelong exposure to slightly raised C-reactive protein (CRP) (15), Interleukin-18 (IL18) (16), regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted protein (RANTES) (17) or beta-carotene (18) levels are unlikely to alter the risk of type 2 diabetes, whereas some evidence for an aetiological association has been suggested for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) (19). Other examples of this approach provide mechanistic insight to disease. For example the association between variation in the FTO gene, that is associated with adiposity, and some cancers, provides some evidence that adiposity has an aetiological role in cancer (20).

In this study, we used the principle of Mendelian Randomization to provide evidence for or against an aetiological role of raised SHBG levels and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Our results indicate that higher SHBG levels may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.

RESULTS

Observed association between SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes risk

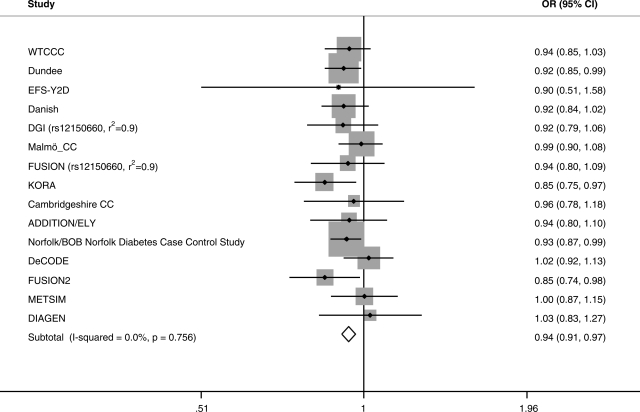

We observed evidence of association between the SHBG SNP rs1799941 and type 2 diabetes (OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.97; P = 2 × 10−5), with the SHBG raising allele associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes (Figs 1 and 2). This result included correction for age, sex and BMI across 14 of the 15 studies (one study is uncorrected), but the result was similar when correcting for age and sex only (OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.97; P = 2 × 10−5). The result was also similar in men (OR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.99; P = 0.009); and women (OR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.89, 0.98; P = 0.003). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in any analysis, either between or within sexes or with and without correction for BMI (all heterogeneity P > 0.15, maximum I2—a measure of the variation in effect size attributable to heterogeneity—29%). There was a trend towards an increased effect in carriers of two copies of the SHBG raising allele, compared with carriers of two copies of the SHBG lowering allele (OR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.85, 0.97; P = 0.006) (uncorrected). The SHBG lowering (G) allele at rs1799941 ranged in allele frequency from 0.72 to 0.75 in individual study controls and from 0.73 to 0.77 in individual study type 2 diabetes patients.

Figure 1.

Triangulation approach to assess how the observed association of the SHBG SNP rs1799941 with type 2 diabetes compares with that expected given the association between rs1799941 and circulating SHBG levels and the difference in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of rs1799941 in type 2 diabetes case–control studies correcting for or matching for BMI, age and sex. OR, odds ratio.

Observed differences in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls

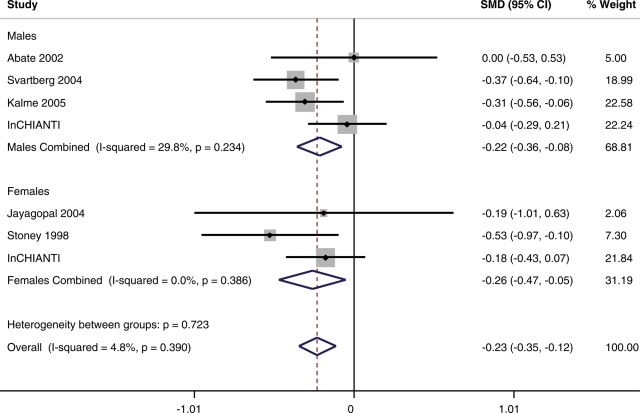

Details of the differences in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls are given in Table 2 and in Figures 1 and 3. SHBG levels were 0.233 (95% CI: −0.35, −0.115) standard deviations lower in type 2 diabetes patients compared with controls, when controlling for BMI. This estimate differed little between men (OR −0.218, 95% CI: −0.360, −0.076) and women (OR −0.264, 95% CI: −0.475, −0.054).

Table 2.

Details of SHBG levels in type 2 diabetes patients and normal glycaemic individuals in seven cross-sectional studies

| Type 2 diabetic patients |

Controls |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age (SD) | BMI (SD) | SHBG |

N | Age (SD) | BMI (SD) | SHBG |

|||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||||

| Men | ||||||||||

| Abate et al. (34)a | 33 | 55 (9) | 27.6 (5.0) | 19.10 | 13.00 | 24 | 45 (9) | 28.2 (7.6) | 19.10 | 13.00 |

| Svartberg et al. (35)b | 55 | N/A | N/A | 43.70 | 21.40 | 1364 | N/A | N/A | 51.80 | 22.00 |

| Kalme et al. (36)c | 109 | N/A | N/A | 63.20 | 29.23 | 152 | N/A | N/A | 71.60 | 25.20 |

| InCHIANTId | 71 | 72.0 (9.4) | 27.80 (3.45) | 85.12 | 46.83 | 476 | 66.6 (16.2) | 26.91 (3.36) | 87.22 | 47.56 |

| TOTAL | 268 | 2016 | ||||||||

| SMD (95%CI) | −0.218 (−0.360, −0.076) | |||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||

| Jayagopal et al. (37)e | 12 | 62 (50–73) | 31.6 (25.1–35.7) | 38.80 | 18.20 | 11 | 56 (48–70) | 32.0 (26.6–44.4) | 42.20 | 17.10 |

| Stoney et al. (38)f | 42 | 64 (6.5) | 28.8 (5.2) | 27.80 | 20.50 | 42 | 63 (6.5) | 28.9 (4.5) | 40.30 | 26.12 |

| InCHIANTI (4) | 67 | 75.7 (9.8) | 29.34 (5.05) | 102.92 | 75.47 | 650 | 68.4 (15.8) | 27.04 (4.58) | 118.22 | 85.17 |

| TOTAL | 121 | 703 | ||||||||

| SMD (95% CI) | −0.264 (−0.475, −0.054) | |||||||||

Data are from individuals of European ancestry matched or corrected for BMI or waist circumference. Women are postmenopausal.

SMD, standardized mean difference; N/A, not available from original publications.

aControls selected to have the same range of BMI as cases. Controls include two individuals and cases include eight individuals of Hispanic ancestry.

bSvartberg et al., SHBG means and SDs are corrected for age and waist circumference.

cKalme et al., SHBG means and SDs are corrected for BMI.

dInCHIANTI SHBG values are geometric values derived from lnSHBG levels corrected for age and BMI.

eControls weight matched to cases. For BMI and age, median and range given.

fStoney et al. controls selected to match cases for BMI and age.

Figure 3.

Details of the correlations between SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes from seven cross-sectional studies of European individuals correcting or matching for BMI or waist circumference.

Approximate expected association between SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes risk

We next tested whether or not the observed association between the SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes was consistent with that expected if SHBG levels alter the risk of type 2 diabetes. We used the estimates of the effect of rs1799941 on circulating SHBG levels and the difference in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls to calculate an approximate expected effect of rs1799941 with type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1). The expected associations were: for men and women combined (OR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.96); for men (OR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.97); and for women (OR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.98). These estimates were similar to those observed.

Associations between SHBG SNPs and type 2 diabetes related intermediate traits

We did not detect any association between the SHBG SNP rs1799941 (or its close proxy rs12150660) and any measures of intermediate type 2 diabetes related traits in population-based studies. These included fasting insulin (P = 0.11, N = 37 864), the HOMAIR measure of insulin resistance (P = 0.24, N = 36 601), fasting glucose (P = 0.52, N = 45 691), the HOMAB measure of beta-cell function (P = 0.04, N = 36,135) [all rs12150660], insulin secretion as assessed by oral glucose tolerance test-based measures of glucose, insulin and C-peptide at 30 and 120 min ( all P > 0.14, N = 5771) or insulin resistance as measured by hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamps (P = 0.94, N = 1229) [all rs1799941].

DISCUSSION

Our study provides evidence that raised circulating SHBG levels reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Our results, together with those from the recent study by Ding et al. (2), provide insight into the role of sex hormones in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes. It has been known for some time that circulating SHBG levels are lower in people with type 2 diabetes compared with non-diabetic individuals, both in cross-sectional comparisons and prospectively. Despite this association, there has been considerable doubt as to the causal relevance of sex hormones in type 2 diabetes. The two genetic studies therefore add considerably to the argument that sex hormones are involved in the aetiology of the disease. This may have important implications for the treatment of diabetes or hypo- and hyper-androgenism in the two sexes.

There are several strengths to our study. First, genotypes are randomly distributed in ethnically homogenous populations, meaning our results are very unlikely to be confounded or biased or secondary to diabetes disease processes. Second, the statistical confidence of the association between the SHBG variant and type 2 diabetes is very strong—of approximately 1 million independent common variants in European genomes, we would only expect 20 to reach this level of statistical confidence by chance. Our results are consistent across 15 studies comprising 27 657 type 2 diabetic patients and 58 481 controls, with all but two studies showing an OR in the expected direction. Third, the ORs we observe between the SHBG rs1799941 SNP and type 2 diabetes are consistent with those expected from a triangulation approach. Fourth, the use of a SNP at the SHBG gene locus strongly associated with circulating SHBG levels means the association is very unlikely to be due to a pleiotropic effect of the variant on another pathway.

There are a few limitations to our study. Most notably we have not found any evidence for the mechanism behind the association between SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes. Despite the large numbers available, we did not observe any associations with various measures of insulin resistance or insulin secretion. This lack of association with intermediate type 2 diabetes traits is not inconsistent with the association with type 2 diabetes. The OR of 0.94 (equivalent to 1.06 for the SHBG lowering allele) is small and previous studies of variants of this magnitude have often not identified any associations with measures of insulin resistance or insulin secretion (21). This may in part be due to the reproducibility of measures based on insulin, which has a very short half life and fluctuates appreciably within individuals. We note, however, that the small effect size does not mean the finding has any less relevance to the question of aetiology, which relies only on the statistical confidence of the findings. A further caveat to our study is that we used a different and much smaller set of patients and controls to estimate the magnitude of the association between circulating SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes compared with the association between the SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes. This difference meant that the estimated effect is very approximate and may be biased by the availability of data from previous publications. The confidence intervals of our estimated effect do not take into account the error in the estimate of the SNP-SHBG levels and so this adds further to the uncertainty of this calculation. Despite these concerns, the estimated and observed ORs for the SHBG SNP effect on type 2 diabetes were very similar.

There are some notable differences between our study and that of Ding et al. (2). While both studies support an association between SHBG SNPs and type 2 diabetes, the effect sizes are very different. Ding et al. report ORs of 1.52 (0.66 inverted) and 1.39 for rs6259 and rs6257, respectively. These ORs are similar to those for SNPs in the TCF7L2 gene, which represent the most strongly associated SNPs in genome wide association studies of type 2 diabetes. There is no evidence of association between rs6259 (a non-synonymous SNP, D356N) and type 2 diabetes in data from 4549 cases and 5579 controls [P=0.72, OR 1.02 [0.92–1.12], all of European ancestry] (22), and this SNP appears to be less strongly associated with SHBG levels than rs1799941, based on data from previous studies (23,24). The other SNP reported by Ding et al., rs6257, is not in HapMap but previously published data (25) indicates that rs1799941 and rs6257 are partially correlated and that rs1799941 drives the association with SHBG levels. These observations, together with our much larger sample size, suggest that the small OR of 0.94 is a closer reflection of the true effect size than that reported by Ding et al.

How might genetically lowered SHBG levels increase the risk of type 2 diabetes? Previous studies suggest that rs1799941 has different effects on total testosterone levels in men and women. Dunning et al. showed that the SHBG lowering allele at rs1799941 is not associated with total testosterone levels in postmenopausal women (N = 1975) (23). This means that women with genetically lower SHBG levels are exposed to proportionally more of the adverse effects of the biologically active unbound testosterone. In contrast, higher testosterone levels are thought to protect against adverse metabolic effects in men and Ahn et al. (25) showed that the SHBG raising allele at rs1799941 is strongly associated with higher total testosterone levels in men (N = 4678). This explanation is complicated by the fact that free testosterone levels are maintained in men by a strong feedback loop whereby luteinizing hormone (LH) production from the pituitary gland in the presence of low androgen levels stimulates testosterone production in the testes. This should mean that genetically lower SHBG levels will not greatly affect free testosterone levels in men. However, there is recent evidence that bound testosterone may be biologically active (26). If this is the case, then men with lower total testosterone due to lower SHBG will be exposed to less of the protective metabolic effects of androgens, despite similar levels of unbound testosterone.

There are additional implications of our results that require further study. First, our results and those of Ding et al. are not altered by adjustment or matching for BMI despite the fact that increased BMI and adiposity are correlated with reduced SHBG levels. This could mean that altered SHBG levels are part of the reason why increased BMI causally increases the risk of type 2 diabetes. Second, a SNP (rs6259) in the SHBG gene has been associated with prostate cancer and there is increasing evidence that there may be a casual link to the inverse association between prostate cancer and type 2 diabetes (27), although our results suggest that this requires additional studies of rs1799941 in prostate cancer (28).

In conclusion, a large type 2 diabetes case–control study provides strong statistical support for a role of SHBG and sex hormones in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our methods were based on the triangulation approach outlined in Figure 1. In summary we used (i) a common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) near the SHBG gene, rs1799941, previously shown to be very strongly associated with SHBG levels; (ii) 27 657 type 2 diabetes patients and 58 481 controls from 15 studies to test the association between this SNP and type 2 diabetes risk; (iii) data from six studies to estimate the magnitude of the association between SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes and (iv) existing data to calculate an approximate expected effect of the SHBG SNP on type 2 diabetes given the magnitude of the SNP versus SHBG levels association and the magnitude of the SHBG levels versus type 2 diabetes association.

Selection of a SNP strongly associated with SHBG levels

Several genetic studies have established unequivocal evidence that common variation close to the SHBG gene influences circulating SHBG levels. We used previously published information to quantify the association between a SNP, rs1799941, 67 base pairs upstream of the SHBG gene and circulating SHBG levels. Several studies have shown consistent associations between rs1799941 and SHBG levels (P < 1 × 10−16) (23–25). Each copy of the A allele is associated with a 0.20 SDs increase in SHBG levels, based on Finnish (NFBC66) and Italian (InCHIANTI) population-based studies, with similar effect sizes in men and women (24).

Observed association between SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes risk

Through collaboration between 15 studies, we assembled a set of 27 657 cases and 58 481 controls. These studies varied in characteristics and ascertainment criteria and details are given in Table 1. All patients and controls were of European ancestry. The SHBG SNP rs1799941 was directly genotyped in all but three studies, two of which used a strongly correlated SNP (rs12150660 r2 = 0.9 with rs1799941), available as part of genome wide association data (FUSION1 and DGI), and a third used a mixture of directly genotyped and imputed data (Decode). Genotyping methods and quality control steps are given in Supplementary Material, Table S1. Individual studies calculated a per allele OR for the A allele at rs1799941, correcting for age, sex and BMI (except publicly available DGI data where cases and controls were matched for gender and BMI, and WTCCC samples, where data for BMI in controls was not available). The FUSION2 study additionally corrected for birth province and used 5 year age category instead of age. We next used the ‘metan’ command in STATAv10 to meta-analyse these results across all 15 studies. This function weighs all studies by the inverse of their variance (a function of SNP frequency and study size) to obtain a per allele estimate of the type 2 diabetes OR for all studies. We quote the OR effect of the SHBG raising allele, which, because raised SHBG levels are correlated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, we expected to be <1.0, if SHBG levels are involved in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes. Given the different levels of SHBG in men and women we repeated analyses stratified by sex.

Table 1.

Characteristics of type 2 diabetes patients and controls from 15 studies

| Study | Type 2 diabeties |

Control |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age |

BMI |

N | Age |

BMI |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Men | ||||||||||

| WTCCC | 1334 | 50.15 | 9.08 | 30.43 | 5.32 | 1042 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dundee | 2205 | 55.38 | 8.81 | 30.78 | 5.36 | 2283 | 59.98 | 11.41 | 27.16 | 3.95 |

| EFS-Y2D | 102 | 40 | 5.45 | 30.63 | 4.9 | 861 | 32.7 | 5.97 | 26.59 | 3.87 |

| Danish | 2049 | 56.55 | 8.87 | 30.24 | 4.88 | 2252 | 47.06 | 9.16 | 26.11 | 3.52 |

| DGIa | 742 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 707 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malmö CC | 1641 | 56.76 | 11 | 29.09 | 4.9 | 1287 | 57.7 | 6.08 | 25.52 | 3.08 |

| FUSION1a,b | 623 | 53.59 | 9.09 | 29.44 | 4.02 | 573 | 63.42 | 7.62 | 27.02 | 3.52 |

| KORAb | 669 | 60.4 | 9.1 | 29.7 | 4.7 | 840 | 60.5 | 9 | 28 | 3.9 |

| Cambridgeshire CCb | 346 | 63.4 | 7.9 | 28.7 | 3.8 | 343 | 63.7 | 7.9 | 27.1 | 3.5 |

| ADDITION/ELYb | 553 | 60.2 | 7.5 | 32.3 | 5.4 | 725 | 61.2 | 9.2 | 27.1 | 3.9 |

| NDCCSb | 3,575 | 66.4 | 10.6 | 29.3 | 4.8 | 3,038 | 58.9 | 9.1 | 26.3 | 3.1 |

| DeCODE | 832 | 55 | 12.1 | 29.7 | 4.9 | 7603 | 64.3 | 16.4 | 27.4 | 4.5 |

| FUSION2 | 646 | 58.3 | 8.82 | 30.23 | 4.96 | 724 | 57.45 | 7.58 | 26.74 | 3.41 |

| METSIMc | 818 | 60.84 | 5.99 | 30.07 | 5.2 | 3372 | 57.98 | 6.4 | 26.25 | 3.46 |

| DIAGEN | 255 | 62.55 | 11.06 | 29.25 | 4.46 | 267 | 55.87 | 14.38 | 26.52 | 3.48 |

| Total | 16 390 | 25 917 | ||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||

| WTCCC | 951 | 49.82 | 9.56 | 32.86 | 7.08 | 1039 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dundee | 1666 | 56.36 | 8.98 | 32.82 | 6.83 | 2414 | 56.97 | 12.04 | 26.89 | 5.17 |

| EFS-YT2D | 89 | 37.88 | 7.18 | 34.14 | 7.78 | 901 | 30.44 | 5.25 | 23.97 | 4.39 |

| Danish | 1398 | 57.35 | 9.89 | 31.28 | 6.28 | 2607 | 46.81 | 8.97 | 25.08 | 4.39 |

| DGIa | 722 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 760 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malmö CC | 1150 | 59.46 | 11.89 | 30.46 | 6.13 | 2210 | 57.34 | 5.96 | 24.79 | 3.83 |

| FUSION1a,b | 470 | 54.03 | 8.98 | 31.2 | 5.25 | 599 | 63.71 | 7.27 | 27.24 | 4.14 |

| KORAb | 538 | 61.6 | 9.4 | 31.8 | 5.8 | 678 | 61.4 | 9.2 | 27.9 | 4.7 |

| Cambridgeshire CCb | 202 | 63.3 | 7.9 | 31.6 | 6.8 | 191 | 63.5 | 7.7 | 27.8 | 5.1 |

| ADDITION/ELYb | 339 | 62.9 | 6.4 | 34.2 | 6 | 885 | 60.5 | 9.1 | 27.1 | 5.4 |

| NDCCSb | 2,481 | 67.1 | 11.4 | 30.8 | 6.5 | 3,390 | 57.8 | 9.3 | 25.9 | 4 |

| DeCODE | 582 | 55.2 | 12.7 | 30.6 | 6 | 16007 | 57.2 | 18.2 | 26.5 | 5.2 |

| FUSION2 | 437 | 61.09 | 7.45 | 31.75 | 5.76 | 463 | 60.92 | 7.34 | 27.14 | 4.6 |

| DIAGEN | 242 | 67.49 | 12.3 | 31.09 | 7 | 420 | 55.93 | 14.09 | 26.62 | 4.78 |

| Total | 11 267 | 32 564 | ||||||||

N/A, clinical characteristics not available separated by sex. Age is the age at diagnosis for diabetic patients unless otherwise stated.

aDGI and FUSION1 studies used proxy SNP (r2 = 0.9) from GWAS data rs12150660.

bAge at recruitment given for these studies.

cMETSIM is a study of men only.

Observed differences in SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes patients and controls

SHBG levels are not routinely measured in type 2 diabetes patients and controls. Instead, we used data from type 2 diabetes studies (four of men only and three of women only) that had measured SHBG levels. These studies were men and women from the InCHIANTI study (24) and the cross-sectional studies published in the meta-analysis conducted by Ding et al. (1), for which we were able to retrieve mean and standard deviation measures of SHBG in cases and controls, were restricted to individuals of European ancestry, and had matched or corrected SHBG levels for body mass index or waist circumference. Details of these studies are given in Table 2. For each study, we tabulated six variables: number of cases, mean case SHBG levels, standard deviation of case SHBG levels, number of controls, mean control SHBG levels and standard deviation of control SHBG levels, using ngmol−1 as the units of SHBG. We performed an inverse variance weighted meta-analysis of these studies, both overall and within sexes, using the ‘metan’ command in STATAv10, to derive a standardized mean difference (SMD) of SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes cases and controls.

Approximation of the expected association between SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes risk

We used the estimates of the effect of rs1799941 on SHBG levels in (i) and the correlation between SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes estimated in (iii) to calculate an approximate expected effect of rs1799941 on type 2 diabetes, assuming that there is an aetiological association between SHBG levels and type 2 diabetes risk. We used the formula:

where SDA is the per allele effect of rs1799941 on circulating SHBG levels expressed as a standard deviation and SMDB is the standardized mean difference (SMD) of SHBG levels between type 2 diabetes cases and controls. This approach has previously been described in the context of diabetes-related traits (29) and the rationale for the formula for approximating SMDs to ORs is described in more detail in Chinn et al. (30). The figure 1.81 is the scaling factor used to approximate ln(ORs) to and from standardized mean differences (30).

Associations between SHBG SNP and type 2 diabetes related traits

To test for associations between the SHBG SNP rs1799941 (or its close proxy rs12150660) and type 2 diabetes related traits, we used data from a variety of sources. For measures of fasting glucose and homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) based measures of insulin resistance, we used data from MAGIC of between 36 135 and 45 691 individuals, details of which are described in detail elsewhere (31). For measures of insulin secretion, we used 5771 individuals from the Danish study, details of which are described in detail elsewhere (32). For measures of whole body/peripheral insulin resistance, we used 1229 individuals from the RISC study (33). All statistical tests were performed using appropriate transformations (described in the relevant publications) and a per allele 1.d.f. test (in keeping with the additive effect of rs1799941 on SHBG levels).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

Collection of the UK type 2 diabetes cases was supported by Diabetes UK, BDA Research and the UK Medical Research Council (Biomedical Collections Strategic Grant G0000649). The UK Type 2 Diabetes Genetics Consortium collection was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Biomedical Collections Grant GR072960). The GWA genotyping was supported by the Wellcome Trust (076113) and replication genotyping by the European Commission (EURODIA LSHG-CT-2004- 518153), MRC (Project Grant G016121), Wellcome Trust (Project Grant 083270/Z/07/Z), Peninsula Medical School and Diabetes UK. The work on the Cambridgeshire case–control, Ely and EPIC-Norfolk studies was funded by support from the Wellcome Trust and Medical research Council (MRC). ADDITION-Cambridge was supported by the Wellcome Trust, MRC, National Health Service R&D support funding and the National Institute for Health Research. The Norfolk Diabetes study is funded by the MRC with support from NHS Research & Development and the Wellcome Trust. The Danish case–control study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation Centre of Applied Medical Genomics for Personalized Disease Prediction, Prevention and Care (LUCAMP) and the Danish Diabetes Association. Inter99 is supported by grants from the Danish Research Counsil, The Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment, Novo Nordisk Inc., Research Foundation of Copenhagen County, Ministry of Internal Affaires and Health, The Danish Heart Foundation, The Danish Pharmaceutical Association, The Augustinus Foundation and The Ib Henriksen Foundation, the Becket Foundation. The ADDITION sub-study Denmark was initiated by: Knut Borch-Johnsen (PI), Torsten Lauritzen (PI) and Annelli Sandbaek. The study was supported by the National Health Services in the counties of Copenhagen, Aarhus, Ringkøbing, Ribe and South Jutland, together with the Danish Research Foundation for General Practice, Danish Centre for Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment, the diabetes fund of the National Board of Health, the Danish Medical Research Council, the Aarhus University Research Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The study received unrestricted grants from Novo Nordisk, Novo Nordisk Scandinavia, Astra Denmark, Pfizer Denmark,GlaxoSmithKline Pharma Denmark, Servier Denmark and HemoCue Denmark. The KORA studies were financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München, Research Center for Environment and Health, Neuherberg, Germany and supported by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN) and the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC Health) as part of LMUinnovativ. Additional funds were provided by the German Diabetes Center (Düsseldorf, Germany), the Federal Ministry of Health (Berlin, Germany) and the Ministry of Innovation, Science, Research and Technology of the state North Rhine-Westphalia (Düsseldorf, Germany). The RISC Study is supported by European Union grant QLG1-CT-2001-01252 and AstraZeneca. Support for FUSION study was provided by the following: American Diabetes Association grant 1-05-RA-140 (R.M.W.) and NIH grants DK069922 (R.M.W.), U54 DA021519 (R.M.W.), DK062370 (M.B.) and DK072193 (K.L.M.). Additional support comes from the National Human Genome Research Institute intramural project number 1 Z01 HG000024 (F.S.C.). DIAGEN study was supported by the Dresden University of Technology funding grant, Med Drive. METSIM: support was provided by grant 124243 from the Academy of Finland. The InCHIANTI study is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging and in part by NIH/NIA grant R01 AG24233-01. I.B. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (077016/Z/05/Z). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Wellcome Trust.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all study participants. E.Z. is a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellow. We acknowledge the contribution of our team of research nurses. We acknowledge the efforts of Jane Collier, Phil Robinson, Steven Asquith and others at Kbiosciences (http://www.kbioscience.co.uk/) for their rapid and accurate large-scale genotyping. We are grateful to the study teams and participants. We thank the technical teams at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the MRC Epidemiology laboratory for genotyping and informatics support. The Danish Inter99 sub-study was initiated by Torben Jørgensen (PI), Knut Borch-Johnsen (co-PI), Hans Ibsen and Troels F. Thomsen. The steering committee comprises the former two and Charlotta Pisinger. We thank all members of field staffs who were involved in the planning and conduct of the MONICA/KORA Augsburg studies. FUSION: We would like to thank the many Finnish volunteers who generously participated in the FUSION, D2D, Health 2000, Finrisk 1987, Finrisk 2002 and Savitaipale studies from which we chose our FUSION GWA and replication. DIAGEN: We are grateful to all of the patients who cooperated in this study and to their referring physicians and diabetologists in Saxony. Mike Weedon is Vandervell Foundation Research Fellow. We gratefully acknowledge Prof Steve Franks for useful discussion.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ding E.L., Song Y., Malik V.S., Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1288–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding E.L., Song Y., Manson J.E., Hunter D.J., Lee C.C., Rifai N., Buring J.E., Gaziano J.M., Liu S. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1152–1163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunaif A. Hyperandrogenic anovulation (PCOS): a unique disorder of insulin action associated with an increased risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Med. 1995;98:33S–39S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin P., Holmang S., Jonsson L., Sjostrom L., Kvist H., Holm G., Lindstedt G., Bjorntorp P. The effects of testosterone treatment on body composition and metabolism in middle-aged obese men. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1992;16:991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon D., Charles M.A., Lahlou N., Nahoul K., Oppert J.M., Gouault-Heilmann M., Lemort N., Thibult N., Joubert E., Balkau B., et al. Androgen therapy improves insulin sensitivity and decreases leptin level in healthy adult men with low plasma total testosterone: a 3-month randomized placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:2149–2151. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.12.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyanov M.A., Boneva Z., Christov V.G. Testosterone supplementation in men with type 2 diabetes, visceral obesity and partial androgen deficiency. Aging Male. 2003;6:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin H.Y., Xu Q., Yeh S., Wang R.S., Sparks J.D., Chang C. Insulin and leptin resistance with hyperleptinemia in mice lacking androgen receptor. Diabetes. 2005;54:1717–1725. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rincon J., Holmang A., Wahlstrom E.O., Lonnroth P., Bjorntorp P., Zierath J.R., Wallberg-Henriksson H. Mechanisms behind insulin resistance in rat skeletal muscle after oophorectomy and additional testosterone treatment. Diabetes. 1996;45:615–621. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant S.F., Thorleifsson G., Reynisdottir I., Benediktsson R., Manolescu A., Sainz J., Helgason A., Stefansson H., Emilsson V., Helgadottir A., et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu P.Y., Wishart S.M., Celermajer D.S., Jimenez M., Pierro I.D., Conway A.J., Handelsman D.J. Do reproductive hormones modify insulin sensitivity and metabolism in older men? A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin. Eur. J. Endocrinol. Eur. Federation Endocr. Soc. 2003;148:55–66. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1480055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrales J.J., Burgo R.M., Garca-Berrocal B., Almeida M., Alberca I., Gonzalez-Buitrago J.M., Orfao A., Miralles J.M. Partial androgen deficiency in aging type 2 diabetic men and its relationship to glycemic control. Metabolism. 2004;53:666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasquali R., Casimirri F., De Iasio R., Mesini P., Boschi S., Chierici R., Flamia R., Biscotti M., Vicennati V. Insulin regulates testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations in adult normal weight and obese men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 1995;80:654–658. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.2.7852532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasquali R., Gambineri A., Biscotti D., Vicennati V., Gagliardi L., Colitta D., Fiorini S., Cognigni G.E., Filicori M., Morselli-Labate A.M. Effect of long-term treatment with metformin added to hypocaloric diet on body composition, fat distribution, and androgen and insulin levels in abdominally obese women with and without the polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2000;85:2767–2774. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey Smith G., Ebrahim S. 'Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner E.J., Kivimaki M., Witte D.R., Lawlor D.A., Davey Smith G., Cooper J.A., Miller M., Lowe G.D., Rumley A., Casas J.P., et al. Inflammation, insulin resistance, and diabetes—Mendelian randomization using CRP haplotypes points upstream. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rafiq S., Melzer D., Weedon M.N., Lango H., Saxena R., Scott L.J., Palmer C.N., Morris A.D., McCarthy M.I., Ferrucci L., et al. Gene variants influencing measures of inflammation or predisposing to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases are not associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2205–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herder C., Illig T., Baumert J., Muller M., Klopp N., Khuseyinova N., Meisinger C., Poschen U., Martin S., Koenig W., et al. RANTES/CCL5 gene polymorphisms, serum concentrations, and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study, 1984–2002. Eur. J. Endocrinol. Eur. Federation Endocr. Soc. 2008;158:R1–R5. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry J.R., Ferrucci L., Bandinelli S., Guralnik J., Semba R.D., Rice N., Melzer D., Saxena R., Scott L.J., McCarthy M.I., et al. Circulating beta-carotene levels and type 2 diabetes-cause or effect? Diabetologia. 2009;52:2117–2121. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herder C., Klopp N., Baumert J., Muller M., Khuseyinova N., Meisinger C., Martin S., Illig T., Koenig W., Thorand B. Effect of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene variants and MIF serum concentrations on the risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Case-Cohort Study, 1984–2002. Diabetologia. 2008;51:276–284. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan P., McKay J., Moore L., Zaridze D., Mukeria A., Szeszenia-Dabrowska N., Lissowska J., Rudnai P., Fabianova E., Mates D., et al. Obesity and cancer: Mendelian randomization approach utilizing the FTO genotype. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009;38:971–975. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grarup N., Andersen G., Krarup N.T., Albrechtsen A., Schmitz O., Jorgensen T., Borch-Johnsen K., Hansen T., Pedersen O. Association testing of novel type 2 diabetes risk alleles in the JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, TSPAN8, THADA, ADAMTS9 and NOTCH2 loci with insulin release, insulin sensitivity, and obesity in a population-based sample of 4,516 glucose-tolerant middle-aged Danes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2534–2340. doi: 10.2337/db08-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeggini E., Scott L.J., Saxena R., Voight B.F., Marchini J.L., Hu T., de Bakker P.I., Abecasis G.R., Almgren P., Andersen G., et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunning A.M., Dowsett M., Healey C.S., Tee L., Luben R.N., Folkerd E., Novik K.L., Kelemen L., Ogata S., Pharoah P.D., et al. Polymorphisms associated with circulating sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:936–945. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melzer D., Perry J.R., Hernandez D., Corsi A.M., Stevens K., Rafferty I., Lauretani F., Murray A., Gibbs J.R., Paolisso G., et al. A genome-wide association study identifies protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn J., Schumacher F.R., Berndt S.I., Pfeiffer R., Albanes D., Andriole G.L., Ardanaz E., Boeing H., Bueno-de-Mesquita B., Chanock S.J., et al. Quantitative trait loci predicting circulating sex steroid hormones in men from the NCI-Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:3749–3757. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammes A., Andreassen T.K., Spoelgen R., Raila J., Hubner N., Schulz H., Metzger J., Schweigert F.J., Luppa P.B., Nykjaer A., et al. Role of endocytosis in cellular uptake of sex steroids. Cell. 2005;122:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gudmundsson J., Sulem P., Steinthorsdottir V., Bergthorsson J.T., Thorleifsson G., Manolescu A., Rafnar T., Gudbjartsson D., Agnarsson B.A., Baker A., et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berndt S.I., Chatterjee N., Huang W.Y., Chanock S.J., Welch R., Crawford E.D., Hayes R.B. Variant in sex hormone-binding globulin gene and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:165–168. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freathy R.M., Timpson N.J., Lawlor D.A., Pouta A., Ben-Shlomo Y., Ruokonen A., Ebrahim S., Shields B., Zeggini E., Weedon M.N., et al. Common variation in the FTO gene alters diabetes-related metabolic traits to the extent expected given its effect on BMI. Diabetes. 2008;57:1419–1426. doi: 10.2337/db07-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2000;19:3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prokopenko I., Langenberg C., Florez J., Saxena R., Soranzo N., Thorleifsson G., Loos R., Manning A., Jackson A., Aulchenko Y., et al. Variants in MTNR1B influence fasting glucose levels. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:77–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grarup N., Rose C.S., Andersson E.A., Andersen G., Nielsen A.L., Albrechtsen A., Clausen J.O., Rasmussen S.S., Jørgensen T., Sandbæk A., et al. Studies of association of variants near the HHEX, CDKN2A/B and IGF2BP2 genes with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin release in 10,705 Danish subjects—validation and extension of genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56:3105–3111. doi: 10.2337/db07-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pascoe L., Tura A., Patel S.K., Ibrahim I.M., Ferrannini E., Consortium T.R., Consortium T.U.T.D.G., Zeggini E., Weedon M.N., Mari A., et al. Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes, CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE, are associated with decreased pancreatic ß-cell function. Diabetes. 2007;56:3101–3104. doi: 10.2337/db07-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate N., Haffner S.M., Garg A., Peshock R.M., Grundy S.M. Sex steroid hormones, upper body obesity, and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2002;87:4522–4527. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svartberg J., Jenssen T., Sundsfjord J., Jorde R. The associations of endogenous testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin with glycosylated hemoglobin levels, in community dwelling men. The Tromso Study. Diabetol. Metabol. 2004;30:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalme T., Seppala M., Qiao Q., Koistinen R., Nissinen A., Harrela M., Loukovaara M., Leinonen P., Tuomilehto J. Sex hormone-binding globulin and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 as indicators of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in elderly men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2005;90:1550–1556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayagopal V., Kilpatrick E.S., Jennings P.E., Holding S., Hepburn D.A., Atkin S.L. The biological variation of sex hormone-binding globulin in type 2 diabetes: implications for sex hormone-binding globulin as a surrogate marker of insulin resistance. Diabetes care. 2004;27:278–280. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoney R.M., Walker K.Z., Best J.D., Ireland P.D., Giles G.G., O'Dea K. Do postmenopausal women with NIDDM have a reduced capacity to deposit and conserve lower-body fat? Diabetes care. 1998;21:828–830. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.