Abstract

A series of non-vanillyl resiniferatoxin analogues, having 4-methylsulfonylaminophenyl and fluorophenyl moieties as vanillyl surrogates, have been investigated as ligands for rat TRPV1 heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Although lacking the metabolically problematic 4-hydroxy substituent on the A-region phenyl ring, the compounds retained substantial agonist potency. Indeed, the 3-methoxy-4-methylsulfonylaminophenyl analog (1) was modestly (2.5-fold) more potent than RTX, with an EC50 = 0.106 nM. Further, it resembled RTX in its kinetics and pattern of stimulation of the levels of intracellular calcium in individual cells, as revealed by imaging. Compound 1 displayed modestly enhanced in vitro stability in rat liver microsomes and in plasma, suggesting that it might be a pharmacokinetically more favorable surrogate of resiniferatoxin. Molecular modeling analyses with selected analogues provide evidence that the conformational differences could affect their binding affinities, especially for the ester versus amide at the B-region.

Keywords: Resiniferatoxin, TRPV1 agonist

1. Introduction

Resiniferatoxin (RTX),1,2 isolated from Euphorbia resinifera, is an extremely potent irritant tricyclic diterpene which is structurally related to phorbol-related diterpenes except for its homovanillyl ester group at C-20.3,4 RTX has proven to function pharmacologically as an ultrapotent agonist for the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel, displaying 103- to 104-fold greater potency than the prototypic agonist capsaicin.5

RTX was found to evoke large inward currents in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and TRPV1 transfected cell lines.6 The actions of RTX are mediated by binding, with picomolar affinity, directly to the capsaicin-binding site on the TRPV1 receptor.7 Whereas capsaicin under normal conditions produces only short term desensitization of the TRPV1 mediated currents, the apparent desensitization to RTX can be of very long duration, lasting for weeks.8,9 RTX is being developed as a potent desensitizing agent for neurons in the treatment of urinary urge incontinence and the pain associated with diabetic neuropathy, as well as for cancer pain.10,11 An enantiocontrolled total synthesis12 and a conformational analysis13 of RTX have been reported.

Structure–activity relations for RTX derivatives have been investigated employing partial modifications starting from RTX or ROPA (resiniferonol orthophenylacetate) based on the three structural regions including the A-region (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl), B-region (C20 ester), and C-region (diterpene).14-20 The analysis indicated that the 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl, C20-ester, C3-keto, and orthophenyl groups represent principal pharmacophores. Indeed, simplified RTX analogues containing these pharmacophores showed potent TRPV1 agonism with high binding affinity.21

In the SAR of the A-region of RTX (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl), any modifications on the phenolic hydroxyl, such as methylation and 2-aminoethylation, led to the reduction in binding affinity and agonism in rat DRG. Although its phenyl surrogate showed dramatic reduction in binding affinity (70-fold), its agonist potency was reduced just by 6-fold compared to RTX. This divergence in potencies between ligand binding and agonism for TRPV1 ligands is not unusual20 and may reflect the distinction between the properties of the small fraction of the receptor at the cell surface and the predominant proportion in internal membranes.22 5-Iodo RTX, prepared semisynthetically from RTX by iodination, displayed good potency in rat and human TRPV1 and shifted the activity from agonism to antagonism.17 The SAR of the B-region (ester) has been investigated through the replacement of the ester by the isosteric amide or thiourea and by insertion or deletion of a carbon between the A and B-regions.18,23 However, all caused the reduction in binding affinity and agonism. The C-region (diterpene) of RTX was partly modified or replaced by the simplified skeleton. The SAR analysis of the C-region indicated that the C3-keto group, as well as the orthophenylacetate, appeared to be critical for activity in the diterpene.18

Although resiniferatoxin represents a promising therapeutic candidate as a potent TRPV1 agonist, its structure includes a vanillyl group (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl) which was regarded as essential for its activity but which is was reported in the case of capsaicin to be subject to rapid metabolism, leading to reduced activity in biological systems.24,25

Recently, we reported that the phenolic hydroxyl group in potent vanilloid receptor agonists could be been replaced with an isosteric methanesulfonamide, resulting in a series of capsaicin antagonists that retained potent binding affinity for rat TRPV1 heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.26 It was also demonstrated that, in contrast with capsaicin, the C-20 phenylacetyl ester of RTX retained substantial activity, albeit somewhat reduced in comparison with RTX, and ring substitutions appeared not to be essential for agonism.4

On the basis of this SAR analysis, we have investigated non-vanillyl RTX analogues in which the 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl group was replaced with non-phenolic phenyl groups with the objective that this might reduce in vivo instability of RTX but retain its high potency for TRPV1. We describe that replacement of the 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl group with fluorophenyl derivatives or methanesulfonamide generated compounds which still retain much activity in cellular assays. Here, we report the syntheses, receptor activities and in vitro metabolic stabilities of 4-methanesulfonamidephenyl and fluorophenyl analogues of RTX.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The RTX analogues were prepared starting from commercially available ROPA (resiniferonol-9,13,14-orthophenylacetate) or its 20-amine equivalent23 by the condensation with the corresponding acids using EDC (1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride) coupling reagent as shown in Schemes 1 and 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of RTX analogues.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of RTX-amide analogue.

2.2. Receptor assay

The synthesized resiniferatoxin analogues were evaluated for their binding affinities (expressed as Ki values) using a competitive binding assay with [3H]RTX and for their agonism/antagonism using a functional 45Ca2+ uptake assay (expressed as EC50 values) for rat TRPV1 heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.26 Capsaicin and resiniferatoxin were used as reference compounds for comparison; the potencies of capsaicin and resiniferatoxin were Ki = 1.81 and 0.043 nM, respectively, and EC50 = 45 and 0.27 nM, respectively.

The 4-phenolic hydroxyl group of RTX was substituted with an isosteric methanesulfonylamido group to give compound 1. The methanesulfonylamido group was an attractive choice because it has a pKa value similar to that of the hydroxyl group but appears to be more stable metabolically. Whereas the binding affinity of 1 was reduced by 5-fold compared to RTX, its functional activity (for agonism) was in fact enhanced 2.5-fold, yielding an EC50 = 0.106 nM (Table 1). Compound 1 thus appeared to be a superior agonist as a surrogate of RTX. It is noteworthy that, for a series of simplified RTX analogues that we had investigated, the substitution of the phenolic hydroxyl with the methylsulfonylamino group had switched the activity of the ligand from agonism to antagonism.26 However, here in the case of the actual ROPA structure constituting the C-region, the methylsulfonylamino group serves as an isostere conferring agonism.

Table 1.

Potencies of RTX analogues for binding to rat VR1 and for inducing calcium influx in CHO/VR1 cells

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | RTX bindinga (Ki = nM) | Agob (EC50 = nM) | Antc | |

| CAP | 1808 | 44.8 | |||||||

| RTX | O | H | OCH3 | OH | H | H | 0.0426 | 0.27 | NEd |

| 1 | O | H | OCH3 | NHSO2CH3 | H | H | 0.228 (±0.051) | 0.106 (±0.031) | NE |

| 2 | O | H | F | NHSO2CH3 | H | H | 0.84 (±0.22) | 2.45 (±0.2) | NE |

| 3 | O | H | H | NHSO2CH3 | H | H | 6.81 (±0.91) | 1.78 (±0.53) | NE |

| 4 | O | F | H | H | H | H | 0.73 (±0.23) | 4.65 (±0.62) | NE |

| 5 | O | H | F | H | H | H | 2.4 (±0.31) | 1.92 (±0.6) | NE |

| 6 | O | H | H | F | H | H | 3.1 (±1.7) | 3.88 (±0.67) | NE |

| 7 | O | F | F | H | H | H | 3.53 (±0.41) | 9.1 (±1.6) | NE |

| 8 | O | F | H | F | H | H | 0.89 (±0.31) | 1.80 (±0.59) | NE |

| 9 | O | F | H | H | F | H | 0.4 (±0.14) | 4.21 (±1.5) | NE |

| 10 | O | F | H | H | H | F | 2.69 (±0.66) | 11.3 (±2.5) | NE |

| 11 | O | H | F | F | H | H | 0.98 (±0.28) | 5.5 (±1.0) | NE |

| 12 | O | H | F | H | F | H | 8.3 (±2.0) | 59(±10) | NE |

| 13 | O | F | F | F | F | F | 135 (±25) | WEe | WEf |

| 14 | NH | H | H | NHSO2CH3 | H | H | 320 (±41) | 375 (±90) | NE |

Receptor binding affinities were assessed in terms of the ability of the compounds to compete for specific binding of [3H]RTX in the CHO/VR1 system and were expressed as the Ki ± SEM.

Potencies as agonists were expressed as EC50 ± SEM, and absolute levels of 45Ca2+ uptake were compared with that induced by a maximally effective concentration of capsaicin in this system, namely 300 nM.

The in vitro antagonistic potencies of the compounds were evaluated by measuring antagonism of the 45Ca2+ uptake induced by 50 nM capsaicin and expressed as the Ki ± SEM, respectively, correcting for competition by capsaicin.

NE: not effective.

Only 23% fractional calcium uptake compared to 300 nM capsaicin.

WE: weakly effective.

Next, the 3-methoxy group of compound 1 was replaced by 3-fluoro or removed to provide compounds 2 and 3, respectively. The modifications led to dramatic reductions in binding affinity by 20-fold in 2 and by 120-fold in 3, and it caused a moderate decrease in agonism by 9-fold in 2 and 7-fold in 3 (Table 1). The results indicated that, in the presence of the 4-methylsulfonylamino group, the 3-methoxy group is of importance for binding to the receptor. This result is in contrast to that with RTX, where removal of the 4-methoxy group to yield tinyatoxin caused only a 3-fold decrease in binding potency27 and a 6-fold loss of biological potency.28 The results are similarly in contrast to those with a simplified RTX C region.26 When the ester group of compound 3 was changed to amide 14, the receptor activity dropped by 50-fold for binding and by 210-fold for agonism. This result mirrors that for the RTX amide, which was 450-fold less potent for binding than was RTX.23 The result confirms that the ester group provides an optimal B-region for receptor activity of RTX analogs, and stands in contrast to the findings with capsaicin, where the ester and amide are very similar.29

Previous structure-activity relationship of RTX analogues demonstrated that the unsubstituted phenylacetyl ester retained substantial activity, albeit reduced potency in comparison with RTX (relative potency: Ki: 0.015, EC50: 0.157).18 This contrasts markedly with the case of capsaicin analogues, where 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy substituents are essential for potent agonism.30

As a complementary strategy to that of substituting the 4-hydroxy group with a methylsulfonylamino group to generate ligands less subject to metabolism, we synthesized the fluorophenyl analogues (4–13), which might reduce the electron density of the phenyl group and protect against electrophilic hydroxylation mediated by cytochrome enzymes.

The three possible monofluorophenyl analogues (4–6) were synthesized. They exhibited moderately reduced activities in both binding affinity (17–74-fold) and agonism (7–17-fold) compared to RTX, which are comparable to those of unsubstituted phenyl analogues (70-fold, 6.5-fold, respectively) (Table 1). The position appears not to be critical for potency. As a next step, the six possible difluorophenyl analogues (7–12) were investigated. Their activities showed moderate to marked reductions in both binding (9.4–195-fold) and agonism (6.7–217-fold), with the more potent ligands similar to those of the monosubstituted analogues. In particular, compounds 8 (2,5-F2) and 9 (2,6-F2) showed significant potency without the 4-phenolic OH. Compared to RTX, the relative affinity of compound 9 was 0.1 and the relative agonism of compound 8 was 0.15.

The pentafluorophenyl analogue (13) was also prepared. It showed relatively very low affinity and a shift in functional activity to partial agonism/antagonism, with the antagonism being predominant.

2.3. Calcium imaging

Changes in intracellular calcium levels in Chinese hamster ovary cells over-expressing TRPV1 show marked differences in response to different vanilloids.31 In particular, the response to capsaicin (at a capsaicin dose approximating its EC50) is rapid and uniform within the population of individual cells and diminishes after reaching an initial maximum. In contrast, the response to resiniferatoxin shows a gradual onset, reflecting marked heterogeneity in the time to response of individual cells. This pattern of response may contribute to the partial dissociation between pungency and desensitization/defunctionalization observed for RTX, where the more gradual activation of TRPV1 in C fiber neurons might reduce the perception of the activation as pain. We wished to determine if the introduction of the methylsulfonylamino group into RTX was able to maintain this pattern of response characteristic of RTX. Compound 1 induced a similar pattern of response in intracellular calcium to that observed for RTX (Fig. 1). As with RTX, the rate of response to compound 1 was gradual and this gradual response again reflected heterogeneity in the time to response of individual cells, with individual cells when responding tending to respond fully.

Figure 1.

Modulation of intracellular calcium levels in response to vanilloid treatment. Chinese hamster ovary cells heterologously expressing rat TRPV1 were preloaded with Fura-2 and treated with capsaicin, RTX, or compound 1 as indicated. The cells were imaged and the 340/380 fluorescence ratio of the Fura-2 was monitored to detect changes in intracellular calcium levels as described.31 Ligand concentrations, chosen to be approximately at their EC50’s for TRPV1, were: capsaicin, 30 nM; RTX, 75 pM; compound 1, 100 pM. (a) In each panel, 20 cells responding to the stimuli are shown; each line represents the response of an individual cell. Data are from a single experiment representative of three independent experiments for capsaicin and RTX and of four experiments for compound 1. (b) The average percent of responding cells as a function of time. Values represent the mean data for 3 (capsaicin and RTX) or 4 (compound 1) experiments. Bars, SEM. The data for capsaicin and RTX are from experiments reported previously;31 the experiments with compound 1 were done in parallel.

2.4. In vitro metabolic stability

The two potent RTX analogues 1 and 8 were selected for further examination of in vitro metabolic elimination and plasma stability compared to RTX. The three compounds were incubated with a rat liver microsomal fraction or with plasma and their concentrations before and after the incubation were compared. The in vitro metabolic stability at 60 min of incubation was expressed as the percent of the initial concentration. Compared to 57.6 (±6.4)% of RTX remaining after 60 min, 81.4 (±5.8)% of compound 1 and 57.9 (±8.6)% of compound 8 remained (Fig. 2). Likewise, relative to 71.7 (±4.0)% of RTX remaining after 240 min incubation with rat plasma, 90.8 (±5.3)% of compound 1 and 88.3 (±4.1)% of compound 8 remained (Fig. 2). Collectively, this observation indicates that compound 1 is more stable than RTX and compound 8 in liver microsomes and plasma, suggesting that compound 1 is a pharmacokinetically more favorable RTX surrogate.

Figure 2.

(a) The comparison of in vitro metabolic stability for RTX derivatives in the presence of rat liver microsomes. The initial concentration was fixed at 10 μg/mL for the three derivatives. The vertical axis indicates the percent of the initial concentration remaining after incubation for 60 min with the microsomes. RTX, resiniferatoxin. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three replicates. **p < 0.01, from RTX value by the unpaired t-test. (b) Comparative metabolic stability of RTX derivatives in the presence of rat plasma. The initial concentration was fixed at 10 μg/mL for the three derivatives. The vertical axis indicates the percent of the initial concentration remaining after the 240 min of incubation. RTX, resiniferatoxin. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three replicates. **p < 0.01, from RTX value by the unpaired t-test.

2.5. Molecular modeling

In order to investigate the structural basis for the binding affinity differences of the synthesized ligands, we performed conformational analyses of 1, 3, 14 and RTX using Grid Search in Tripos SYBYL molecular modeling program. The resulting low energy conformers in the gas phase were solvated with water, and then the solvated molecules were further energy minimized to find the lowest energy conformations in aqueous solution.

Our conformational study showed that RTX can exist in three major conformers in water with small energy differences less than 2 kcal/mol (Fig. 3a), so that the low energy conformers can be interchangeable among them and adjust well to the active conformation at the binding site of TRPV1. These results coincide with the previous report, confirmed by NMR and modeling, that the A-region phenyl ring of RTX was found extended away from the diterpene core in non polar solution but in polar solution it showed bent and intermediate conformers along with the extended conformer.13

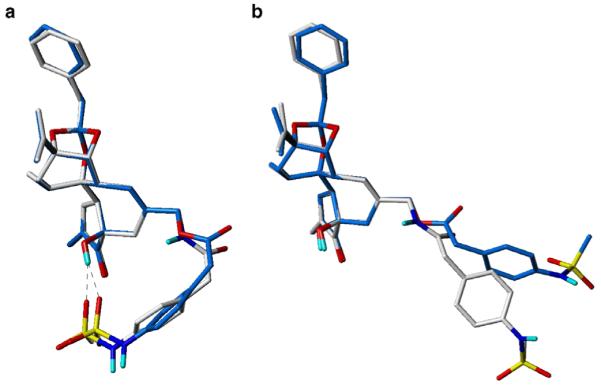

Figure 3.

The representative low energy conformers of RTX and its analogue 1. (a) The low energy conformers of RTX. Carbon atoms are shown in green colors. (b) Two major low energy conformers of compound 1, a sulfonamide analogue of RTX. The lowest energy conformer shows a bent conformation with a distinctive internal H-bonding. Carbon atoms are shown in magenta or purple. Non-polar hydrogens are undisplayed for clarity.

In addition, the sulfonamide analogues of RTX were found to exist in two major conformers as shown in Figure 3b. One conformer, which is shown in purple, is similar to that of RTX. But surprisingly, the other one, which is the lowest energy conformer displayed in magenta, indicates that the sulfonamide group forms very distinctive internal H-bonding with the hydroxyl group of the diterpene core. The energy difference between the extended conformer and the bent conformer was about 4–7 kcal/mol. Therefore, it appears to require more energy to break that internal H-bond to establish the active conformation at the binding site. That might be why the sulfonamide series have lower binding affinities than RTX.

On the other hand, the absence of methoxy group in the sulfonamide analogue 3 lowers the binding affinity about one order of magnitude compared with the analogue 1. It seems that the methoxy group might play an important role for binding, and according to Chou et al.,32 the methoxy group of RTX interacts with Tyr555 at the binding site of TRPV1.

In the sulfonamide series, the replacement of ester to amide at the B-region decreases the binding affinity and that can be explained by the conformational differences between them. As shown in Figure 4, the resulting conformers of the compound 14, which has an amide group at the B-region, show distinctive conformational differences compared with compound 3. The A-region phenyl ring of compound 14 has a quite different orientation than that of RTX, making it difficult to maintain the π-π stacking interaction with Phe543 at the binding site.32 In addition, the amide analogue might not be able to fit well at the binding site because the amide conformation is much more restricted than that of the ester group.

Figure 4.

Low energy conformers of sulfonamide analogues of RTX, 3, and 14. (a) Lowest energy conformers, showing bent conformation due to internal H-bonding, (b) Extended conformers as alternative low energy conformations. Carbon atoms are shown in sky-blue and white for compounds 3 and 14, respectively. Non-polar hydrogens are undisplayed for clarity.

For more direct comparison of the effect of the amide and ester, we performed another conformational study with an RTX analogue which has an amide at the B-region.18 Consistent with the markedly reduced biological potency of the RTX-amide analogue, the lowest energy conformer of the RTX-amide analogue was quite different from that of RTX. In the RTX-amide analogue, the B-region is more bent toward the diterpene core (Fig. 5). Even though it does not form an internal H-bond as occurs with compounds in the sulfonamide series, the planar amide bond seems to make it possible to form this bent conformation. As mentioned above, it was reported that the low energy conformers of RTX can be clustered into several groups in a polar environment13 and that coincides with our computational results. In the case of RTX-amide analogue, our study showed that its several possible conformers converged on one lowest energy conformer after further minimization, resulting in the global minimum.

Figure 5.

Low energy conformers of RTX and RTX-amide. The representative low energy conformers of RTX-amide analogue are converged on one bent conformer, resulting in the global minimum. Carbon atoms are displayed in green and brown for RTX and RTX-amide, respectively. Non-polar hydrogens are undisplayed for clarity.

Based on our conformational analyses of a series of RTX analogues along with RTX, we could conclude that the sulfonamide group at the terminus of the C region or an amide at the B-region give somewhat distinctive conformational restrictions to the ability of the RTX analogues to adjust their bioactive conformation at the binding site and this may underlie their decreased binding affinities. Although the lowest energy conformer in solution might not be the precise active conformation at the binding site, it provides an insight into structural factors that should contribute to their binding affinity differences. For more precise simulation, homology modeling of TRPV1 and docking studies of the ligands are under investigation.

3. Conclusion

We have investigated the structure activity relationships and the metabolic stability of RTX analogues by replacing the 4-hydroxyl-3-methoxyphenyl group in the A-region with 4-methylsulfonylamidophenyl or fluorophenyl groups. Among the derivatives, compound 1, having a 4-methylsulfonylamino-3-methoxyphenyl group, showed excellent agonism with a value of EC50 = 0.106 nM for rat TRPV1 in CHO cells, which was 2.5-fold more potent than RTX. Compound 1 likewise induced a similar kinetic pattern of the cellular response as evidenced by intracellular calcium levels as did RTX, whereas capsaicin induced a very different pattern of response. Finally, the stability studies with rat liver microsomes and plasma incubation demonstrated that compound 1 was a metabolically more stable surrogate of RTX. Our conformational study indicated that the sulfonamide group in the lowest energy conformer of compound 1 could form an internal H-bond with the diterpene core, resulting in a more bent conformation than that of RTX. Also, compared with the ester, the amide bond at the B-region might confer conformational restriction, which could affect the binding affinity.

The results not only suggest that compound 1 is a promising RTX-like agonist but further emphasize that the relative agonist/antagonist character of TRPV1 ligands is dependent on the entire structure and cannot be isolated to the A-region of the molecule.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

All chemical reagents were commercially available. ROPA was purchased from LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA. Melting points were determined on a Büchi Melting Point B-540 apparatus and are uncorrected. Silica gel column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60, 230–400 mesh, Merck. Proton NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL JNM-LA 300 at 300 MHz. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm units with Me4Si as a reference standard. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Perkin–Elmer 1710 Series FTIR. Mass spectra were recorded on a VG Trio-2 GC–MS. Elemental analyses were performed with an EA 1110 Automatic Elemental Analyzer, CE Instruments.

4.2. General procedure for coupling

To a solution of resiniferonol-9,13,14-orthophenylacetate (14 mg, 0.03 mmol) and acid (0.06 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was added 1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (15 mg, 0.08 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (1.3 mg). After being stirred for 2 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and extracted with CH2Cl2 several times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel with EtOAc/hexanes (1:2) as eluent to afford the product.

4.2.1. 3-Methoxy-4-(methylsulfonylamino) analogue (1)

82% Yield, white solid, mp = 203–205 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.47–7.49 (m, 2H, H-1 and ArH-5), 7.37–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 6.85–6.92 (m, 2H, ArH-2,6), 6.74 (s, 1H, NHSO2), 5.92 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.74 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.60 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 19.3 Hz, H-20), 4.24 (s, 1H, H-14), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.64 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.23 (s, 2H, H-2′), 3.12 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.98 (s, 3H, SO2CH3), 2.59 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.45 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5a), 2.20 (br s, 1H, OH), 2.16 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8 and 14.2 Hz, H-12a), 2.09 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5b), 1.85 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.56 (d, 1H, J = 14.2 Hz, H-12b), 1.55 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.98 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 706 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C38H43NO10S: C, 64.66; H, 6.14; N, 1.98; S, 4.54. Found: C, 64.89; H, 6.17; N, 1.94; S, 4.50.

4.2.2. 3-Fluoro-4-(methylsulfonylamino) analogue (2)

84% Yield, white solid, mp = 76–78 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.53 (t, 1H, J = 8.05 Hz, ArH-5), 7.48 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.37–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 7.14 (d, 1H, J = 10.9 Hz, ArH-2), 7.10 (d, 1H, J = 7.93 Hz, ArH-6), 6.59 (s, 1H, NHSO2), 5.90 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.74 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.60 (t of AB, 2H, H-20), 4.23 (s, 1H, H-14), 3.65 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.23 (s, 2H, H-2′), 3.11 (d, 2H, H-8 and H-10), 3.07 (s, 3H, SO2CH3), 2.59 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.45 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5a), 2.33 (br s, 1H, OH), 2.16 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8 and 14.2 Hz, H-12a), 2.07 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5b), 1.85 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.57 (d, 1H, J = 14 Hz, H-12b), 1.55 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.98 (d, 3H, J = 7 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 694 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C37H40FNO9S: C, 64.05; H, 5.81; N, 2.02; S, 4.62. Found: C, 64.29; H, 5.86; N, 1.98; S, 4.57.

4.2.3. 4-(Methylsulfonylamino) analogue (3)

84% Yield, white solid, mp = 95–96 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.45 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.38 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 5H, 3 H of Ph and 2 H of Ar), 7.18 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar), 6.38 (s, 1H, NHSO2), 5.85 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.72 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.56 (s, 2H, H-20), 4.18 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, H-14), 3.63 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (s, 2H, H-2′), 3.07 (m, 2H, H-8 and H-10), 3.02 (s, 3H, SO2CH3), 2.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.35 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5a), 2.15 (br s, 1H, OH), 2.13 (dd, 1H, J = 8.7, 14.2 Hz, H-12a), 2.03 (d, 1H, J = 18.7 Hz, H-5b), 1.83 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.55 (d, 1H, J = 14.2 Hz, H-12b), 1.54 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.96 (d, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 676 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C37H41NO9S: C, 65.76; H, 6.12; N, 2.07; S, 4.74. Found: C, 65.98; H, 6.17; N, 2.04; S, 4.70.

4.2.4. 2-Fluoro analogue (4)

83% Yield, white solid, mp = 54–56 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.48 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.37–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.24–7.3 (m, 4H, Ph, 1H of Ar), 7.05–7.2 (m, 3H, Ar), 5.90 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.73 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.60 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 24 Hz, H-20), 4.23 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, H-14), 3.72 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.23 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 13.9, 16 Hz, H-2′), 3.11 (br s, 1H, H-8 and H-10), 2.59 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.48 (d, 1H, J = 19 Hz, H-5a), 2.09–2.2 (m, 3H, H-12a, H-5b and OH), 1.85 (d, 3H, J = 1.3 Hz, H-19), 1.58 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.54 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.99 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 601 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H37FO7: C, 71.98; H, 6.21. Found: C, 72.28; H, 6.23.

4.2.5. 3-Fluoro analogue (5)

80% Yield, white solid, mp = 54–56 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.48 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.37–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.24–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 6.95–7.1 (m, 4H, Ar), 5.90 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.73 (d, 2H, J = 3.5 Hz, H-16), 4.60 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 25.9 Hz, H-20), 4.23 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz, H-14), 3.67 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.24 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.11 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.09 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.58 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.47 (d, 1H, J = 18.4 Hz, H-5a), 2.17 (dd, 1H,, J = 8.7, 14.3 Hz, H-12a), 2.06–2.1 (m, 2H, H-5b and OH), 1.86 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.55 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.54 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.99 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 601 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H37FO7: C, 71.98; H, 6.21. Found: C, 72.30; H, 6.24.

4.2.6. 4-Fluoro analogue (6)

82% Yield, white solid, mp = 56–58 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.47 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.37–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.24–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 6.98–7.1 (m, 4H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.73 (d, 2H, J = 4 Hz, H-16), 4.58 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 25.7 Hz, H-20), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 3.3 Hz, H-14), 3.64 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.23 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.06 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.57 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.46 (d, 1H, J = 23.5 Hz, H-5a), 2.12–2.2 (m, 2H, H-12a and OH), 2.06 (d, 1H, J = 23.5 Hz, H-5b), 1.85 (m, 3H, H-19), 1.57 (d, 1H, J = 17.9 Hz, H-12b), 1.54 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.99 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 601 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H37FO7: C, 71.98; H, 6.21. Found: C, 72.27; H, 6.25.

4.2.7. 2,3-Difluoro analogue (7)

92% Yield, white solid, mp = 62–64 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.46 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 7.0–7.1 (m, 3H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.71 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.58 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 25.3 Hz, H-20), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, H-14), 3.73 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.24 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.09 (br s, 1H, H-8 and H-10), 2.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.47 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.06–2.18 (m, 3H, H-12a, H-5b and OH), 1.83 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.55 (d, 1H, J = 14.6 Hz, H-12b), 1.52 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.96 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.18; H, 5.84.

4.2.8. 2,4-Difluoro analogue (8)

94% Yield, white solid, mp = 54–56 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.45 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 4H, Ph, 1 H of Ar), 6.79–6.86 (m, 2H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.71 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.58 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 22.1 Hz, H-20), 4.21 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, H-14), 3.66 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (dd of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.07 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.47 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.06–2.17 (m, 3H, H-12a, H-5b and OH), 1.83 (m, 3H, H-19), 1.56 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.52 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.97 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.20; H, 5.83.

4.2.9. 2,5-Difluoro analogue (9)

94% Yield, pale yellow solid, mp = 50–52 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.45 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 6.88–7.05 (m, 3H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.73 (m, 2H, H-16), 4.59 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 23.6 Hz, H-20), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, H-14), 3.67 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.08 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.57 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.47 (d, 1H, J = 18.9 Hz, H-5a), 2.14 (dd, 1H, J = 8.7, 14.3 Hz, H-12a), 2.10 (d, 1H, J = 18.9 Hz, H-5b), 2.03 (br s, 1H, OH), 1.83 (dd, 3H, J = 1.3, 2.7 Hz, H-19), 1.56 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.51 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.97 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.18; H, 5.83.

4.2.10. 2,6-Difluoro analogue (10)

93% Yield, pale yellow solid, mp = 52–54 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.45 (br s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 4H, Ph and 1 H of Ar), 6.90 (m, 2H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.71 (d, 2H, J = 1 Hz, H-16), 4.59 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.2, 23.5 Hz, H-20), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, H-14), 3.74 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 14.2, 15.8 Hz, H-2′), 3.10 (br s, 2H, H-8 and H-10), 2.57 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.48 (d, 1H, J = 18.9 Hz, H-5a), 2.06–2.17 (m, 3H, H-12a, H-5b and OH), 1.83 (dd, 3H, J = 1.4, 2.8 Hz, H-19), 1.55 (d, 1H, J = 14.2 Hz, H-12b), 1.52 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.96 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.22; H, 5.82.

4.2.11. 3,4-Difluoro analogue (11)

94% Yield, white solid, mp = 70–72 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.46 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 7.05–7.15 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.98 (m, 1H, Ar), 5.88 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.71 (d, 2H, J = 5 Hz, H-16), 4.57 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 24.8 Hz, H-20), 4.21 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, H-14), 3.60 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.07 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.05 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.45 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.14 (dd, 1H, J = 8.7, 14.3 Hz, H-12a), 2.07 (br s, 1H, OH), 2.05 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5b), 1.83 (d, 3H, J = 1.2 Hz, H-19), 1.53 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.52 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.96 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.13; H, 5.85.

4.2.12. 3,5-Difluoro analogue (12)

93% Yield, white solid, mp = 50–52 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.46 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.4 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 6.82 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.68–6.78 (m, 2H, Ar), 5.89 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.71 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.58 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 27.3 Hz, H-20), 4.21 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, H-14), 3.62 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.07 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.47 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.06–2.17 (m, 3H, H-12a, H-5b and OH), 1.83 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.55 (dd, 1H, J = 4.1, 14.3 Hz, H-12b), 1.52 (s, 3H, H-17), 0.96 (d, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 619 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H36F2O7: C, 69.89; H, 5.87. Found: C, 70.15; H, 5.84.

4.2.13. Pentafluoro analogue (13)

92% Yield, white solid, mp = 73–75 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.46 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.38 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 3H, Ph), 5.91 (s, 1H, H-7), 4.72 (s, 2H, H-16), 4.60 (dd of AB, 2H, J = 12.1, 21.9 Hz, H-20), 4.23 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, H-14), 3.76 (s, 2H, H-2′′), 3.21 (t of AB, 2H, H-2′), 3.12 (s, 1H, H-8), 3.10 (s, 1H, H-10), 2.57 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.51 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.1–2.18 (m, 2H, H-12a and H-5b), 2.07 (s, 1H, OH), 1.84 (s, 3H, H-19), 1.56 (d, 1H, J = 14.3 Hz, H-12b); MS (FAB) 673 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C36H33F5O7: C, 64.28; H, 4.95. Found: C, 64.49; H, 4.91.

4.2.14. Amide analogue (14)

82% Yield, white solid, mp = 143–147 °C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.44 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.35–7.38 (m, 2H, Ph), 7.2–7.3 (m, 5H, 3 H of Ph and 2 H of Ar), 7.18 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar), 6.48 (br s, 1H, NHSO2), 5.58 (br s, 1H, H-7), 5.51 (t, 1H, J = 5.9 Hz, NHCO), 4.72 (m, 2H, H-16), 4.12 (d, 1H, J = 2.98 Hz, H-14), 3.92 (dd, 1H, J = 6.3 and 15.2 Hz, H-2a”), 3.79 (dd, 1H, J = 5.6 and 15.2 Hz, H-2b”), 3.56 (s, 2H, H-20), 3.20 (br s, 2H, H-2′), 3.01 (m, 5H, H-8, H-10 and CH3), 2.54 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.36 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5a), 2.26 (br s, 1H, OH), 2.11 (dd, 1H, J = 8.7 and 14.2 Hz, H-12a), 2.00 (d, 1H, J = 18.8 Hz, H-5b), 1.81 (m, 3H, H-19), 1.54 (m, 4H, H-12b and H-17), 0.94 (d, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz, H-18); MS (FAB) 675 (MH+); Anal. Calcd for C37H42N2O8S: C, 65.86; H, 6.27; N, 4.15; S, 4.75. Found: C, 66.09; H, 6.30; N, 4.13; S, 4.71.

4.3. Comparison of in vitro metabolic stability for resinferatoxin (RTX), compounds 1 and 8 in rat liver microsome and plasma

The stability of RTX analogues was compared in the presence of a Sprague-Dawley rat liver microsomal fraction (BD Bioscience, Bedford, USA) or in freshly prepared rat plasma. For the micro-somal stability study, 1 mL of reaction mixture contained a 10 μL aliquot of the aqueous solutions of 1 mM NADPH and 5 mM MgCl2 in 0.5 mL of phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH adjusted to 7.4), and 0.5 mg microsomal protein. The mixture was pre-warmed in a 37 °C water bath under constant agitation (i.e., 50 oscillations per min). The temperature and agitation were maintained throughout the experiment until the termination of the reaction. The reaction was initiated by the addition of a 10 μL aliquot of the drug solution (final concentration of the derivatives in the mixture was 10 μg/mL). For the rat plasma stability study, a 10 μL aliquot of the drug solution (final concentration of the analogues in the mixture was 10 μg/mL) was added to pre-warmed rat plasma (0.5 mL). The reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 mL of methanol after 0 (i.e., immediately after the initiation of the reaction) or 60 min for microsomal stability and 240 min for the plasma stability. The concentration of the analogues in the incubation media was measured by LC-MS system. HPLC separation was carried out in a Waters 2695 HPLC system with an analytical column (Phenomenex C18, 4.6 × 150 m, i.d. of 5 μm). The mobile phase, 0.1% HCOOH:acetonitrile (10:90, v/v), was run at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. MS analysis was performed by a Waters micromass ZQ in the positive ESI mode. In this study, the selective ion monitoring at m/z 629, m/z 706 and m/z 619 for RTX, compounds 1 and 8 was selected for the quantification of the derivatives.

4.4. Molecular modeling

The structures of tested compounds were built with Concord for 3D and energy minimized using the MMFF94s force field (method: powell; termination: gradient 0.05 kcal/mol Å; and max iterations: 1,000,000) implemented in the SYBYL molecular modeling program (Tripos, Inc.).

The conformational analyses of each compound were performed using the SYBYL Grid Search method (force field: MMFF94s; charges: MMFF94; minimization method: powell; termination: gradient 0.05 kcal/mol Å; and max iterations: 10,000). The torsion angles which were defined for the grid search included C1–C2–X3–C4, C2–X3–C4–C5, and C3–C4–C5–C6.

In the analyses, 1728 unique conformers were found for compounds 1, 3 and RTX, respectively, and 288 conformers were found for compound 14. Among them, the lowest energy conformer and highly probable conformers were chosen and solvated with water (shape of the cluster: box; radii type: Tripos; and with the default number of solvent layers). The solvated conformers were energy minimized using the Tripos force field and the Gasteiger–Hückel charges. Then, the resulting conformers were superimposed using the fit atoms function in SYBYL. All computational studies were performed with Tripos SYBYL molecular modeling program package version 8.0 on a Linux (RHEL 4.0 Intel Xeon processor 5050) workstation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R11-2007-107-02001-0 and R01-2007-000-20052-0 from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF), the National Core Research Center program (No. R15-2006-020) of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and KOSEF through the Center for Cell Signaling & Drug Discovery Research at Ewha Womans University, and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute.

References and notes

- 1.Appendino G, Szallasi A. Life Sci. 1997;60:681. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg PM, Szallasi A, Acs G. Resiniferatoxin, an ultrapotent capsaicin Analogue. In: Wood JN, editor. Capsaicin in the study pain. Academic Press; London: 1993. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hergenhahn M, Adolf W, Hecker E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;19:1595. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adolf W, Sorg B, Hergenhahn M, Hecker E. J. Nat. Prod. 1982;45:347. doi: 10.1021/np50021a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Neuroscience. 1989;30:515. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szallasi A, Szabo T, Biro T, Modarres S, Blumberg PM, Krause JE, Cortright DN, Appendino G. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:428. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biro T, Acs G, Acs P, Modarres S, Blumberg PM. J. Invest. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 1997;2:56. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.1997.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Simon SA. Brain Res. 1998;809:246. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00853-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szallasi A, Joo F, Blumberg PM. Brain Res. 1989;503:68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bley KR. Exp. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2004;13:1445. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.11.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DC, Iadarola MJ, Perkowski SZ, Erin H, Shofer F, Laszlo KJ, Olah Z, Mannes AJ. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1052. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wender PA, Jesudason CD, Nakahira H, Tamura N, Tebbe AL, Ueno Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12976. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Victory SF, Appendino G, Vander Velde DG. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1998;6:223. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)10029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appendino G, Ech-Chahad A, Minassi A, Bacchiega S, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:132. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seabrook GR, Sutton KG, Jarolimek W, Hollingworth GJ, Teague S, Webb J, Clark N, Boyce S, Kerby J, Ali Z, Chou M, Middleton R, Kaczorowski G, Jones AB. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;303:1052. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonnell ME, Zhang S-P, Dubin AE, Dax SL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:1189. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahl P, Foged C, Tullin S, Thomsen C. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:9. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walpole CSJ, Bevan S, Bloomfield G, Breckenridge R, James IF, Ritchie T, Szallasi A, Winter J, Wrigglesworth R. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:2939. doi: 10.1021/jm960139d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appendino G, Cravotto G, Palmisano G, Annunziata R, Szallasi A. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:3123. doi: 10.1021/jm960063l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acs G, Lee J, Marquez VE, Blumberg PM. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;35:173. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Kim SY, Park S, Lim J-O, Kim J-M, Kang M, Lee J, Kang S-U, Choi H-K, Jin M-K, Welter JD, Szabo T, Tran R, Pearce LV, Toth A, Blumberg PM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toth A, Blumberg PM, Chen Z, Kozikowski AP. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:282. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acs G, Lee J, Marquez VE, Wang S, Milne GWA, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:301. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly CA, Yost GS. Drug Metab. Rev. 2006;38:685. doi: 10.1080/03602530600959557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrigglesworth R, Walpole CSJ, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, Hughes GA, James I, Masdin KJ, Winter J. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4942. doi: 10.1021/jm960512h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, Lee J, Kang M, Shin M, Kim JM, Kang SU, Lim JO, Choi HK, Suh YG, Park HG, Oh U, Kim HD, Park YH, Ha HJ, Kim YH, Toth A, Yang Y, Tran R, Pearce LV, Lundberg DJ, Blumberg PM. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3116. doi: 10.1021/jm030089u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Brain Res. 1991;547:335. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90982-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt RJ, Evans FJ. Inflammation. 1979;3:273. doi: 10.1007/BF00914184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walpole CSJ, Wrigglesworth R, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, James IF, Masdin KJ, Perkins MN, Winter J. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2373. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walpole CSJ, Wrigglesworth R, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, James IF, Perkins MN, Reid DJ, Winter J. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2362. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toth A, Wang Y, Kedei N, Tran R, Pearce LV, Kang SU, Jin MK, Choi HK, Lee J, Blumberg PM. Life Sci. 2005;76:2921. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou MZ, Mtui T, Gao Y-D, Kohler M, Middleton RE. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2501. doi: 10.1021/bi035981h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]