Abstract

The relaxivities (R-values) of the Gd(DTPA)2− ions in a series of skim-milk solutions at 0–40% milk concentrations were measured using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The R-value was found to be approximately linearly proportional to the concentration of the solid component in the milk solution. Using the R-value at 20% solid component (approximately the solid concentration in bovine nasal cartilage (BNC)), the glycosaminoglycan concentration in BNC can be quantified using the MRI dGEMRIC method without the customary scaling factor of two. This finding is also supported by the measurements using 23Na NMR spectroscopy, 23Na inductively-coupled-plasma (ICP) analysis, and biochemical assay. The choice of the R-value definition in the MRI dGEMRIC method is discussed – and the definition of Gd(DTPA)2− ions as “ millimole per volume of tissue (or milk solution for substitution)” should be used.

Keywords: Cartilage, relaxivity, Glycosaminoglycans, MRI, dGEMRIC, 23Na NMR, ICP, biochemical assay

Introduction

As one of the three major molecular components (water, collagen, and proteoglycan) in articular cartilage, proteoglycans play a critical role in maintaining the mechanical stiffness of the tissue because they have heavily sulfated side-chains of glycosaminoglycan (GAG), which carry a high concentration of negative charges contributing to the stiffness of the tissue. Several experimental methods in MRI have been proposed to detect the loss of GAG, which is regarded as one of the early signs of the tissue degradation leading to the clinical diseases such as osteoarthritis. Among these methods, a proton-based MRI method by Bashir, Gray and Burstein (1) could measure the GAG concentration in articular cartilage by the administration of paramagnetic contrast agent, Gd(DTPA)2− (gadolinium diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid). The central concept of this method is that since Gd(DTPA)2− is negatively charged, the contrast agent will distribute itself within articular cartilage in a spatially inverse relationship to the concentration of the negatively charged GAG molecules. Since gadolinium (Gd3+) is a paramagnetic ion and its presence in the tissue will reduce the T1 relaxation of proton, a map of GAG concentration in cartilage can be constructed based on two T1 maps, one before and one after the Gd administration. This method has been termed as dGEMRIC (delayed Gadolinium-Enhanced MRI of Cartilage) in clinical MRI literature (2–7).

Quantitatively, a set of three equations has been derived to calculate the GAG content using this method, based on the Donnan equilibrium theory (1,8,9),

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where T1 and T1Gd are the T1 values in the tissue as measured before and after the Gd administration respectively (In this paper, T1 and T1Gd are written as T1before and T1after); [Gd]t and [Gd]b are the Gd concentrations in tissue and bath (soaking solution) respectively; R is the relaxivity of the Gd ions in saline; [Na+]b is the sodium concentration in the bath; FCD and [GAG]t are the fixed charge density and the GAG concentration in tissue respectively. SF in Eq(2) is a scaling factor, which was introduced for the reason to be discussed below. The two constants in Eq(3), “−2” and “502.5”, come from the estimates that there are 2 moles of negative charges per mole of disaccharide with a molecular weight of 502.5 g/mole (10,11).

The validations (1,10,12) of these quantitative relationships were carried out using bovine cartilage with an R-value of 4.5 (mM sec)−1, based on the measurements of saline solution at 1.5 Tesla magnet. The FCD of cartilage from the dGEMRIC method was found to be about 50% of that by the sodium NMR method if there was no scaling factor in Eq(2) (i.e., SF=1). These authors have attributed this discrepancy to two reasons: Gd(DTPA)2− being a divalent anion and cartilage having a two-compartment system (1). A scaling factor of two was subsequently introduced in the calculation of GAG using Eq(2) (1,13). However, Fishbein et al (14) performed the measurements of GAG in bovine nasal cartilage (BNC) using Gd(DTPA)2− (divalent anion) and Gd-DOTA− (a monovalent anion paramagnetic contrast agent) and showed that both of these reasons wouldn't result in such discrepancy.

This discrepancy in GAG quantification does not affect the in vivo applications of the dGEMRIC method in human MRI, which aims to monitor the local variation of GAG quantity related to the onset of the tissue lesion. However, it is a source of concern for any quantitative measurement. In particular, the use of saline's R-value seems at odds with the common reasoning that the ion's relaxivity must be somewhat dependent on the concentration of the macromolecular content (15–18). This present study investigates this discrepancy using BNC, which lacks the complex histological zonal structures that are common in articular cartilage (19), and is also regarded to have a homogeneous distribution at both molecular and morphological levels. Three additional techniques (biochemical assay, 23Na NMR (20), 23Na Inductively Coupled Plasma Emission Spectroscopy (ICP) method) were also used to verify the results from the MRI dGEMRIC technique.

Material and Methods

Samples of Bovine Nasal Cartilage

Bovine nasal cartilage, harvested from a local slaughter house (Yale, MI), was immersed in saline (154 mM NaCl in deionized water) and kept in refrigerator at −20 °C before experiment. Two big BNC blocks from two different locations in the animal were presented in this report (Block 1 and Block 2). Several different sized specimens were cut from each BNC block. For the MRI dGEMRIC and biochemical experiments, each specimen was about 1.5×1.5×10 mm in size and weighed about 15mg. For 23Na NMR experiment (liquefied by the concentrated HCl or as intact blocks), each specimen was about 50 mg in weight. For the ICP experiments, each specimen was about 100 mg in weight. The numbers of the specimen in each experiment are summarized in Table 1. Before these experiments, all BNC specimens were soaked in saline solution for more than 10 hours to achieve 23Na equilibrium. During our experiments, we have found that there are small but measurable differences in the GAG concentrations in BNC harvested from different locations of the same animal. Consequently, the data from the two BNC blocks is presented separately in Table 1.

Table 1.

GAG concentrations (wet weight) in BNC by different methods and the P-values from the Mann-Whitney test.

| dGEMRIC MRI | 23Na NMR | 23Na ICP | Biochemical Assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original (R=4.17, SF=2) | Modified (R=5.77, SF=1) | |||||

| Block 1 | GAG (mg/ml) | 131.9±11.6 (n=4) | 83.4±6.5 (n=4) | 85.6±2.6 (n=4) | 87.1±1.9 (n=3) | 96.8±3.3 (n=8) |

| P-value | 0.0286 | 0.875 | reference | 0.627 | 0.0095 | |

| Block 2 | GAG (mg/ml) | 107.9±4.9 (n=7) | 70.1±2.7 (n=7) | 69.6±3.0 (n=3) | 68.1±5.9 (n=7) | 86.7±7.6 (n=7) |

| P-value | 0.0167 | 1.000 | reference | 0.833 | 0.0006 | |

Furthermore, over 20 pieces of BNC tissue were soaked in 10μg/ml trypsin for 10 to 120 minutes for a partial GAG depletion (21). After the trypsin immersion, the tissue blocks were soaked in fresh saline for more than 10 hours to remove trypsin. Following the MRI T1 experiment, both ends of these trypsin-treated tissue blocks were trimmed by about 1mm and the remaining central portions were digested immediately for GAG assay as described below. (The difference in the GAG concentrations in the trypsin-treated tissue from different locations was not detectable. Consequently, the data from trypsin-treated blocks were put together.)

Dependence of Gd-DTPA Relaxivity on Macromolecular Content at 7.0 T

Different amounts of skim-milk powder (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) were added to saline to obtain a series of milk stock with 0%, 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% of solid skim milk by weight. (The macromolecular content in articular cartilage has been reported to be in the ranges of 22.5 – 32.5% (15,16). The macromolecular content in BNC is about 20% according to our measurement, which is similar to the literature (22,23).) For each skim milk stock, eight concentrations of Gd(DTPA)2− (0, 0.2mM, 0.4mM, 0.7mM, 1.0mM, 1.5mM, 2.0mM, 4.0mM) were prepared by adding contrast agent Gd(DTPA)2− (Magnevist, Berlex, Wayne, NJ) to the milk stock. Consequently, the Gd(DTPA)2− concentration in this study was defined as the millimole per volume of skim milk solution.

Microscopic MRI (μMRI) dGEMRIC Procedure

Microscopic MRI (μMRI) experiments were performed at room temperature (about 20°C) on a Bruker AVANCE II 300 NMR spectrometer equipped with a 7-Tesla/89-mm vertical-bore superconducting magnet and micro-imaging accessory (Bruker Instrument, Billerica, MA). A homemade 4mm solenoid coil was used in the μMRI experiments. Quantitative T1-imaging experiments used a magnetization-prepared T1-imaging sequence (24), which has two well-separated timing segments: a leading inversion-recovery segment and a subsequent imaging segment in which all timings are kept constant. Because only the timing of the leading segment is altered during the experiments, the effect of T1 weighting during the leading contrast segment can be calculated unambiguously. This approach is similar to what has been used for the quantitative T2 imaging in our lab (25,26).

The echo time (TE) of the imaging sequence was 7.2 ms; the repetition time (TR) of the imaging experiment was 1.5 s for the tissue before it was soaked in Gd(DTPA)2− solution, and 0.5 s for the tissue after it was soaked in 1 mM Gd(DTPA)2− solution. The recovery time of the leading contrast segment had five increments (0, 0.4, 1.1, 2.2, 4.0 s for tissue before soaking; 0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0 s for tissue soaked in the 1.0mM Gd(DTPA)2− solution). Sufficient time (~ 10 hours) was given to allow the establishment of an equilibrium in the Gd(DTPA)2− ion transportation in the cartilage (16). The T1 relaxation time in cartilage was calculated by the fitting of the imaging data on a pixel-by-pixel basis with an equation y = A(1– B *exp(t/T1)), where A is the maximum signal amplitude, t is the recovery time delay and B is a constant which is less than 2 if TR is less than 5T1 or the inversion pulse is imperfect. The in-plane pixel resolution was 26.0 μm, and the slice thickness was 1 mm.

Although the calculation of GAG requires both T1before and T1after for each specimen, it is actually not necessary to measure the T1before for each specimen. This is because (1) the T1before values of bulk BNC are highly consistent among different specimens in our preliminary experiments (data not shown), and (2) a slight deviation of T1before has little influence on the final GAG value (since the T1before is much bigger than T1after, cf Eq(1)). We hence set T1before to be 1.456 s, which was the average of 3 specimens that were measured in our lab. This practice shortens the experimental time considerably, since the T1before experiments would have a long TR.

Unlike earlier studies in literature (1,4) where the T1 value in cartilage was measured by NMR spectroscopy, we used the imaging method to measure the T1 distribution in BNC after the trypsin immersion. This is because the degradation of cartilage by trypsin is never homogeneous (27), which could result in error in the GAG determination by the NMR spectroscopy of bulk specimen. In addition, the imaging approach offers the possibility of eliminating some abnormal pixels that are related to the condensation of water on the block surface or some non-BNC tissue in the block (eg, membrane).

1H NMR Spectroscopy

Proton NMR spectra of the saline and milk solutions were obtained on the same Bruker NMR spectrometer with a 5-mm high-resolution spectroscopy probe at room temperature. The T1 value was measured by a standard inversion-recovery pulse sequence with 16 recovery times, approximately logarithmically equally-spaced according to the actual T1 values of different Gd(DTPA)2−-doped skim milk concentrations. A repetition time of approximately 5 times the actual T1 value was used.

23Na NMR Spectroscopy

Sodium NMR spectra of the freshly prepared NaCl solutions at different concentrations (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 400 mM) and the BNC specimens (either intact BNC blocks or liquefied BNC solutions) were obtained on the same NMR spectrometer with a commercial 15-mm 1H/23Na imaging probe at room temperature. The BNC liquids and tissue blocks were loaded into standard 5 mm NMR tubes for measurements. To minimize the experimental error, a volume of 100 μl solution (or about 50 mg BNC blocks with addition of 50 μl deionized water) was used for each sample and a home-made NMR tube holder was used to make sure that the sample was always at the center of the probe. The 23Na NMR spectroscopy experiment followed the protocol by Shapiro et al (28), except that a 200 μs preacquisition delay was used for a flatter baseline. This 200 μs preacquisition delay could result in about 2% underestimate of sodium concentration in BNC measurement according to the different linewidths of 23Na spectra between NaCl solution and BNC sample in our experiment. A 200 ms repeat time, which is more than 5 times of T1, was used.

During the experiments, we found that the 23Na concentration in tissue by NMR spectroscopy is highly consistent, no matter if we used BNC blocks or their liquefied solution (data not shown). This 23Na NMR result was consistent with the results reported in literature (11,17,28), where 23Na in cartilage was considered 100% visible. Consequently, the 23Na concentration is reported by averaging data from both liquefied and intact BNC.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Determination of 23Na

A set of ICP experiments was also carried out to determine the GAG concentration in 10 specimens of BNC. These BNC specimens were first liquefied by concentrated HCl over night and then 10 times diluted by deionized water and sent out for the 23Na ICP analysis to two different labs (Soil Testing and Research Analytical Laboratory, University of Minnesota, and ICPMS & XRF Laboratory, Dept. of Geological Sciences, Michigan State University). In addition to the BNC samples, six standard saline solutions (154mM Na) were also analyzed for calibration purpose. The results from the two labs are highly consistent.

Biochemical Assay of GAG

A modified DMMB (1,9-dimethylmethylene blue) dye assay (29) was used to analyze the GAG content in each BNC specimen. The BNC tissues were weighed and converted to volume by the measured density of 1.12 g/ml before the biochemical analysis. After digestion with enzyme papain (1:10 ratio at 65 °C in an oven for overnight), aliquot volumes of 5 or 10 μl from the samples were taken for the glycosaminoglycan measurement spectrophotometrically. A Blyscan dye reagent (Biocolor Ltd, County Antrim, United Kingdom) was used to bind to GAGs. Absorbance was measured at 656 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer. Standard curves for the GAG analysis were generated by assaying the known concentrations of chondroitin sulfate sodium salt from bovine cartilage (C6737-5G, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis).

The GAG content in the aliquot taken for analysis was then used to obtain the total GAG concentration present in the specimen and is expressed as mg/ml when normalized to the wet weight of the tissue. Other experimental details regarding this biochemical assay can be found elsewhere (30,31).

Calculation of GAG Concentration

The quantitative images of Gd(DTPA)2−, FCD and GAG concentration in the tissue were calculated according to Eq.(1) to Eq.(3), which allowed the calculation of the 2D images of GAG concentration. For comparison, the GAG concentrations from the same data were calculated using two sets of formula: (1) a R-value of saline (4.17 (mM sec)−1 in this study) and a scaling factor SF of 2 in Eq(2) (this is the original method by Bashir et al (1) and has been termed as `original'); and (2) a R-value of 20% skim milk (which is 5.77 (mM sec)−1 in this study) and a scaling factor SF of 1 (this is termed as `modified').

For quantitative 23Na NMR or ICP study, the following formula, which is also originated from the Donnan equilibrium theory (1,8,9), was used to substitute Eq.(2) to calculate the FCD content and subsequently the GAG content:

| (4) |

where [Na +]t is the sodium concentration in the tissue.

Statistical Analysis

Data groups were evaluated for significant differences using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test on a commercial software Prism 4 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA). When the two tailed P-value was less than 0.05, the medians of two groups of measurements would be considered significantly different. The GAG concentration from the 23Na NMR spectroscopy was used as the reference value.

Results

Relaxivity of Gd(DTPA)2− in Skim Milk Solutions

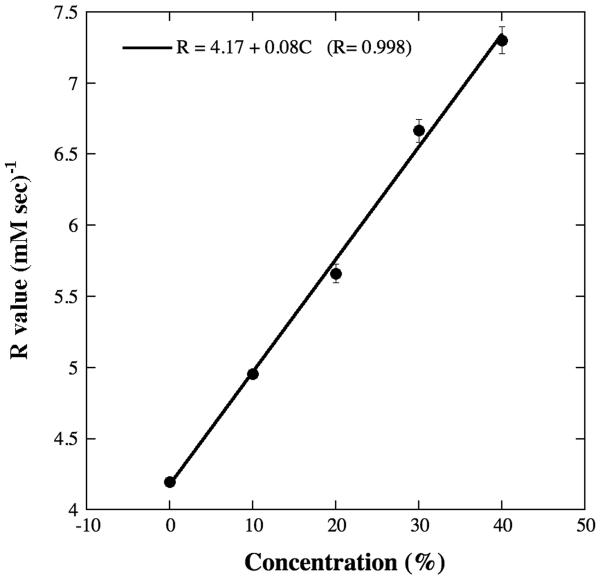

The relaxivity (R-value) of Gd(DTPA)2− ions was determined by measuring the T1 relaxation in different concentrations of skim-milk, as the following. By doping the same milk concentration stock with different amounts of Gd(DTPA)2− and measuring the T1 at each doping, one can get a R-value at this particular milk concentration. By repeating the experiments using different milk concentrations, one can obtain a plot of R-values as a function of solid component concentrations, shown in Fig 1. The relaxivity of the saline is 4.17 (mM sec)–1, in good agreement with the relaxivity values of Gd(DTPA)2− in saline in literature (16,18).

Fig 1.

The relaxivity of Gd(DTPA)2− as the function of skim-milk powder concentrations in saline. The solid line represents a linear fit to the data. `C' in the linear fit is the GAG concentration. The errors are from the fitting of a set of experimental data at different concentration.

It is clear from Fig 1 that the relaxivity of Gd(DTPA)2− in the macromolecular solutions (skim-milk powder in saline) is approximately a linear function of the milk concentration within the concentration range of 0–40%, as:

| (5) |

where `Milk%' is in the unit of the percentage concentration of the macromolecular component in the solution. (The correlation coefficient of the linear fitting in Fig 1 was 0.998.) Hence the R-value increases in this experiment from 4.17 (mM sec)−1 in pure saline to 7.37 (mM sec)−1 in 40% milk concentration. In this report, an R-value of 5.77 (mM sec)−1 has been used for the MRI cartilage analysis, which corresponds to the solid concentration of 20% (the solid concentration of our BNC specimens). With this R-value, we find that there is no need to use the scaling factor of 2 in Eq.(2).

23Na NMR Calibration and Measurement

Fig 2 shows the calibration curve of the NaCl solutions with different concentrations by using NMR spectroscopy. The 23Na data were fitted by a linear function through the origin, with a fitting correlation of 0.99991. This high correlation in line fitting demonstrated the accuracy of the 23Na NMR measurement in our specimens. This result agrees well with an earlier study (28).

Fig 2.

The calibration curve of NMR intensity (area) versus the known 23Na concentration, fitted linearly. `C' in the linear fit is the sodium concentration.

Summary of GAG Results

The GAG results of BNC by dGEMRIC method are summarized in Table 1, together with the GAG results from all other methods. The statistical analyses comparing each group of measurements with the reference group (the 23Na NMR measurement) are also included in the Table. Four conclusions can be drawn from Table 1. (1) The GAG concentration by the modified dGEMRIC method is in excellent agreement with the GAG values obtained for the same specimen using both 23Na ICP and 23Na NMR spectroscopy. In contrast, the GAG concentration by the original dGEMRIC method consistently resulted in a large (statistically significant) disagreement between the MRI results and the comparable methods. (2) These GAG concentrations are consistent with the reported values in literature (22,23). (3) The measurements from Block 1 by all methods were consistently larger than the corresponding measurements from Block 2. We speculated that this difference between Block 1 and Block 2 was caused by the fact that these two blocks were harvested from the different locations of the animal (i.e., tissue heterogeneity). Further experiments are needed to verify this issue. (4) The GAG concentration from the biochemical assay is about 10−20% larger than those from our comparative methods.

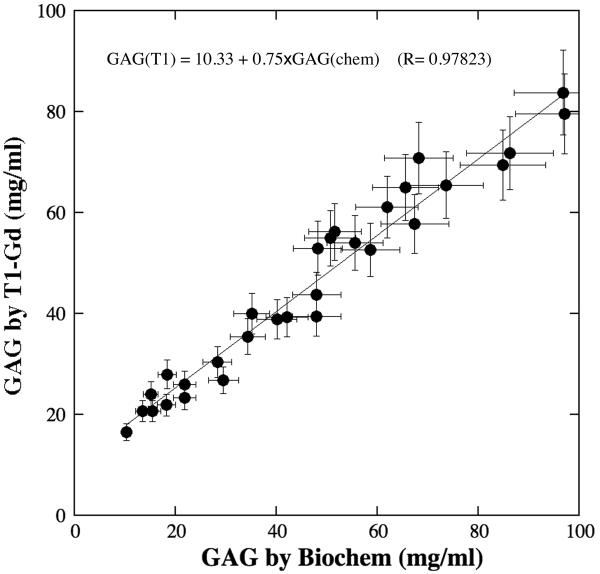

GAG results of BNC after degraded by trypsin

After the BNC specimens were degraded by trypsin, the GAG concentration by our modified dGEMRIC method was plotted against that from biochemical assay, shown in Fig. 3. In general, a linear relationship between the GAG concentrations between these two methods is apparent. Closely, the correlation between the two methods seems to depend upon the concentration of GAG. When the GAG concentration is high (80–100 mg/ml by biochemical assay) (i.e., weak GAG depletion by trypsin), the GAG concentration from biochemical assay is larger than that from the modified dGEMRIC method. When the GAG concentration became lower to 40–60 mg/ml, the GAG concentration from biochemical assay is in good agreement with that from the modified dGEMRIC method. When the GAG concentration is low (10–30 mg/ml) that corresponds to the heavy trypsin degradation, the GAG concentration from biochemical assay seems lower than that from the modified dGEMRIC method.

Fig 3.

GAG concentration by the modified dGEMRIC method versus GAG concentration by biochemical assay after the BNC was degraded by trypsin, where a 10% of measured value was used as the error in the plotting. The straight line is the linear fit of the data.

We consider this variation in the correlation to be not by accident but by the use of a constant R-value in the calculation – we did not use a different R-value when the tissue was degraded. Since the R-value is dependent of the concentration of macromolecules (Fig 1), a lower R-value should be used to calculate the GAG concentration when the BNC was degraded by trypsin. According to our simulation (data not shown), a 10% decrease in the R-value can result in approximately a 10% reduction in the GAG calculation. As a matter of fact, this dependency of R-value on the macromolecular concentration can be an issue for the quantitative application of dGEMRIC method in general - because the macromolecular content in articular cartilage varies with depth, as indicated in Ref. (16,31).

Discussion

In this study, we have nearly exhausted all possible techniques that can be used to quantify the GAG concentration in bovine nasal cartilage. The data summarized in Table 1 clearly show that both the 23Na NMR measurements and the 23Na ICP measurements agree well with the measurements by our modified dGEMRIC method; while the biochemical measurements are consistently higher by about 10–20%. These quantitative measurements are also consistent with the data in literature. For example, Fishbein et al recently determined the GAG concentrations to be 282±83 μg/mg dry weight and 74.3 to 81.4 μg/mg wet weight in two reports (22,23), which correspond to the wet weight equivalent values of 63.2±18.6 mg/ml and 83.2 to 91.2 mg/ml respectively, if a density of 1.12 g/ml and 80% water in BNC was used for conversion. In addition, our 23Na results agree well with two reports in literature (11,28), which showed that the sodium concentrations in cartilage by the ICP method were almost the same as that from the 23Na NMR method.

The relaxivity of Gd-DTPA as the function of macromolecular content

The experimental value of Gd(DTPA)2− ions' relaxivity (R-value) in cartilage is a critically important parameter in the quantification of GAG concentration in cartilage using the dGEMRIC method. There are two important aspects regarding the GAG calculation, the R-value determination and the scaling factor of two in the previous application of Eq.(1–3).

The initial work of this topic had considered the R-values to be nearly constant for a number of systems including saline, homogenous biomaterials and cartilage (1,2,10,32). Several reports later pointed out that the R-value in biological system should be a function of its solid composition concentration (15,18). Both quadratic (15) and linear (16) functions were found in different homogenous systems. In this work, we show that the R-value of Gd(DTPA)2− in the skim milk solution is a linear function of the milk concentration (Fig 1). Table 2 further summarizes the relaxivity of Gd(DTPA)2− determined by a number of research groups at different magnetic field strengths.

Table 2.

The relaxivity of Gd-DTPA2− ions in unit of (mM s)−1

| Magnetic Field Strength (Tesla) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 4.7 | 7 | 8.45 | 9.4 | |

| Saline | 4.83±0.09a | 4.5±0.2b | 4.81±0.11c | 4.02±0.14c | 4.17e | 3.87±0.06a 4.35±0.10c |

3.74±0.01d |

|

| |||||||

| Relaxivity in homogenous materials (% of solid composition) | quadratic | linear | nearly constant for a number of materials ~4.1a | linear | |||

| 5.2 (10%)b | 4.96 (10%)e | 4 (10%)d | |||||

| 6.2 (20%)b | 5.75 (20%)e | 4.26 (20%)d | |||||

| 7.5 (30%)b | 6.55 (30%)e | 4.52 (30%)d | |||||

| 9 (40%)b | 7.34 (40%)e | 5.04 (40%)d | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Intact cartilage | 6.28±0.24c | 4.08±0.08a 4.70±0.07c |

|||||

One factor that can affect the R-value might arise from the definition of the Gd concentration in the solution. In our work, we first dissolved the dry solid milk powder in the saline to make the 10–40% concentration of milk solutions; then we doped the fixed volume of the milk solution with the small quantity of Gd(DTPA)2− solution to make the final milk solution to contain 0.2 mM to 4 mM of Gd(DTPA)2−. Therefore, our Gd concentration in the milk solution is defined as millimole per volume of milk solution. In contrast, several previous studies had defined the solution as the “millimole per kg of water (or saline)” (10,15,16,33). This subtle difference in the definition/preparation of the milk solutions could have a profound impact on the R-value determination. We have measured in a separate test (data not shown) that at 10% milk concentration, one only needs about 93% solvent to make the final solution. This means that the nominal value of Gd concentration defined as `millimole per kg of water (or saline)' is bigger than the nominal value of Gd concentration defined as `millimole per volume of milk solution', which would result in a smaller R-value.

Though either definition in the Gd concentration might be valid as long as it is clear, we consider the concentration per sample volume to be more appropriate for the calculation of the Gd relaxivity in cartilage for GAG measurement in dGEMRIC technique. In the original papers by Bashir et al (1,10), the unit of Gd, FCD and GAG concentration in the tissue was defined in volume of tissue. To calculate the Gd concentration of the tissue with the unit of mM (in volume of tissue), the unit of R-value should be defined as (mM Sec)−1 (in volume of cartilage tissue). To calculate the R-value in the unit of (mM Sec)−1 (in volume of cartilage tissue (or skim milk solution in this report)), the Gd concentration should be defined as millimole per volume of cartilage tissue (or skim milk solution for substitution here).

The Scaling Factor and the R-value Definition in dGEMRIC Method

The multidisciplinary results in Table 1 show that the best correlation is to use the R-value defined as mM (in volume of tissue) and to set the Scaling Factor to one in Eq.(2). If one uses this modified calculation in dGEMRIC method, which is directly from Donnan theory, one can obtain more accurate correlation between the non-invasive MRI method and other quantitative measurements. If one uses the original calculation in dGEMRIC method, the MRI results are consistently about 50% higher than the results from other quantitative measurements. A particularly important correlation is between the dGEMRIC method and the 23Na method, because both have the same physical origin -- Donnan equilibrium theory. It is clear that the GAG concentration by the original dGEMRIC method is about 50% larger, while the results by our modified method agree well with that from the 23Na methods.

Note that because of the difficulty to obtain the accurate R-value for bovine nasal cartilage, the R-value of 5.77 (mM sec)−1 in this report came from the skim milk solution, which could introduce some error to the final GAG value. However, based on the result of Stanisz and Henkelman (15), such substitution is reasonable and shouldn't result in any major error. Because a 10% decrease of R-value can result in approximately a 10% reduction of GAG value according to our simulation, the R-value of cartilage is indeed a critical factor in quantitative measurement of GAG in cartilage by the dGEMRIC method.

In our previous quantitative GAG studies of canine articular cartilage (31,34), we have found that the GAG concentration using Eq(2) and Eq(3) as in the original dGEMRIC method (SF = 2, R=4.17 (mM Sec)−1, 7T MRI system) is constantly 30–50% larger than that of biochemical assay, but has much better correlation when the R-value of 6.4 (mM sec)−1 and SF of 1 were used (corresponding to 27.5% skim milk), as long as the Gd concentration in the milk solution was defined as millimole per volume of skim milk solution as in the modified dGEMRIC method.

The Correlation of GAG Measurement among Different Techniques

Each experimental technique clearly has its own errors and `bias'. For example, our biochemical result was about 10–20% higher than the three comparable results in Table 1, which supported the statement by Shapiro et al (17) that “proteoglycan assay is never considered to be 100% quantitative”. Indeed, there are many experimental issues which can contribute to the errors in DMMB measurement of GAG (30,35–37), including the choice of standard GAG calibration (for example, the absorbance reading of dextran sulfate, heparin, chondroitin 4-sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate and dermatan sulfate for the same concentration is different; the maximum difference was found between dextran sulfate and keratin sulfate; the reading of dextran sulfate is more than two times of that of keratin sulfate (35); the presence of DNA, RNA and hyaluronan, which can also bound the dye reagent; the stability of GAG-dye complex; the nonlinearity in the GAG calibration curve; and the protein in the tissue and ion in the solution.) As long as a consistent procedure is used, the results should be comparable, which can serve as an indication of the GAG quantity in tissue.

Conclusion

The dGEMRIC method is becoming a key method in MRI monitoring of cartilage lesion (2). Since the value of clinical MRI is in the visualization of early lesions, comparing the regional GAG variations among cartilage at different sites of one joint or between two joints is more valuable than the quantitative determination of the actual GAG concentration in cartilage. In contrast, this study probes the quantitative correlation of GAG concentration measurements among different methods in the lab. We found that an appropriate definition for the concentration of Gd ions in macromolecule material is critically important in the calculation of GAG concentration by the MRI dGEMRIC method. If the R-value of the Gd ions was set to be the relaxivity of ions in the 20% solid milk solution, the GAG concentration in bovine nasal cartilage can be quantified without the customary scaling factor of two in the original dGEMRIC technique, provided that the Gd concentration in the milk solution was defined as millimole per volume of skim milk solution. This result is supported by the results from three additional techniques, 23Na NMR spectroscopy, 23Na ICP spectroscopy, and the biochemical assay.

Acknowledgement

Y Xia is grateful to the National Institutes of Health for the R01 grants (AR 45172, AR52353). The authors are indebted to Dr. A Bidthanapally (Dept of Physics, Oakland University) for technical guidance in the biochemical assay and critical comments on the manuscript. The authors also thank C Roy Inc (Yale, Michigan) for providing the bovine cartilage specimens, Ms. Janelle Spann (Michigan Resonance Imaging, Rochester Hills, Michigan) for providing the Gd contrast agent, Dr Christopher Chen (Hospital for Special Surgery, New York) and Dr Clifford Les (Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit) for technical assistance in GAG quantification, and Mr. Farid Badar (Oakland University) for the assistance in specimen harvesting.

Grant Support: NIH R01 grants (AR 45172, AR 52353)

References

- 1.Bashir A, Gray ML, Burstein D. Gd-DTPA2- as a measure of cartilage degradation. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(5):665–673. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashir A, Gray ML, Boutin RD, Burstein D. Glycosaminoglycan in articular cartilage: in vivo assessment with delayed Gd(DTPA)(2-)-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;205(2):551–558. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.2.9356644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trattnig S, Mlynarik V, Breitenseher M, Huber M, Zembsch A, Rand T, Imhof H. MRI visualization of proteoglycan depletion in articular cartilage via intravenous administration of Gd-DTPA. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(4):577–583. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurent D, Wasvary J, O'Byrne E, Rudin M. In vivo qualitative assessments of articular cartilage in the rabbit knee with high-resolution MRI at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(3):541–549. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiderius CJ, Olsson LE, Leander P, Ekberg O, Dahlberg L. Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) in early knee osteoarthritis. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):488–492. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YJ, Jaramillo D, Millis MB, Gray ML, Burstein D. Assessment of early osteoarthritis in hip dysplasia with delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-A(10):1987–1992. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan N, Shetty SK, Williams A, Mikulis B, McKenzie C, Burstein D. Delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the meniscus: an index of meniscal tissue degeneration? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1507–1511. doi: 10.1002/art.22592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maroudas A, Muir H, Wingham J. The correlation of fixed negative charge with glycosaminoglycan content of human articular cartilage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;177:492–500. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maroudas A. Physicochemical properties of articular cartilage. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult articular cartilage. 2nd ed. Pitman Medical; Kent, England: 1979. pp. 215–290. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bashir A, Gray ML, Hartke J, Burstein D. Nondestructive imaging of human cartilage glycosaminoglycan concentration by MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(5):857–865. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199905)41:5<857::aid-mrm1>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesperance LM, Gray ML, Burstein D. Determination of Fixed Charge Density in Cartilage Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J Orthopaedic Research. 1992;10:1–13. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedig M, Bae W, Temple M, Sah R, Gray M. [GAG] profiles in “normal” human articular cartilage. Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society.2005. p. 0358. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen RG, Burstein D, Gray ML. Monitoring glycosaminoglycan replenishment in cartilage explants with gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Orthopaedic Research. 1999;17(3):430–436. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbein KW, Gluzband YA, Spencer RG. Measurements of fixed charge density in Bovine Nasal Cartilage using Gd-DOTA. Proceedings of the 10th Annual Meeting of the Intl Soc Magn Reson Med.2002. p. 065. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanisz GJ, Henkelman RM. Gd-DTPA Relaxivity Depends on on Macromolecular Content. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(5):665–667. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<665::aid-mrm1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieminen MT, Rieppo J, Silvennoinen J, Toyras J, Hakumaki JM, Hyttinen MM, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. Spatial assessment of articular cartilage proteoglycans with Gd-DTPA-enhanced T1 imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48(4):640–648. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro EM, Borthakur A, Gougoutas A, Reddy R. 23Na MRI accurately measures fixed charge density in articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(2):284–291. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillis A, Gray M, Burstein D. Relaxivity and diffusion of gadolinium agents in cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48(6):1068–1071. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia Y. Magic Angle Effect in MRI of Articular Cartilage - A Review. Invest Radiol. 2000;35(10):602–621. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai H, Potter K, McFarland E. Determination of Ion Activity Coefficients and Fixed Charge Density in Cartilage with 23Na magnetic Resonance Microscopy. J Chem Eng Data. 1996;41:970–976. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, Vernier-Singer M, Lust G, Jelinski LW. Self-Diffusion Monitors Degraded Cartilage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323(2):323–328. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fishbein KW, Gluzband YA, Kaku M, Ambia-Sobhan H, Shapses SA, Yamauchi M, Spencer RG. Effects of formalin fixation and collagen cross-linking on T2 and magnetization transfer in bovine nasal cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(6):1000–1011. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fishbein KW, Canuto HC, Bajaj P, Camacho NP, Spencer RG. Optimal methods for the preservation of cartilage samples in MRI and correlative biochemical studies. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(5):866–873. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia Y. Relaxation Anisotropy in Cartilage by NMR Microscopy (μMRI) at 14 μm Resolution. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(6):941–949. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, Lust G. Origin of cartilage laminae in MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7(5):887–894. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia Y, Moody J, Burton-Wurster N, Lust G. Quantitative In Situ Correlation Between Microscopic MRI and Polarized Light Microscopy Studies of Articular Cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(5):393–406. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moody HR, Brown CP, Bowden JC, Crawford RW, McElwain DL, Oloyede AO. In vitro degradation of articular cartilage: does trypsin treatment produce consistent results? J Anat. 2006;209(2):259–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro EM, Borthakur A, Dandora R, Kriss A, Leigh JS, Reddy R. Sodium visibility and quantitation in intact bovine articular cartilage using high field (23)Na MRI and MRS. J Magn Reson. 2000;142(1):24–31. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbosa I, Garcia S, Barbier-Chassefiere V, Caruelle JP, Martelly I, Papy-Garcia D. Improved and simple micro assay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans quantification in biological extracts and its use in skin and muscle tissue studies. Glycobiology. 2003;13(9):647–653. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg082. Epub 2003 May 2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panin G, Naia S, Dall'Amico R, Chiandetti L, Zachello F, Catassi C, Felici L, Coppa GV. Simple spectrophotometric quantification of urinary excretion of glycosaminoglycan sulfates. Clin Chem. 1986;32(11):2073–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia Y, Zheng S, Bidthanapally A. Depth-dependent Profiles of Glycosaminoglycans in Articular Cartilage by μMRI and Histochemistry. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(1):151–157. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donahue KM, Burstein D, Manning WJ, Gray ML. Studies of Gd-DTPA relaxivity and proton exchange rates in tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32(1):66–76. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieminen MT, Toyras J, Laasanen MS, Silvennoinen J, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. Prediction of biomechanical properties of articular cartilage with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. J Biomech. 2004;37(3):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng S, Xia Y, Bidthanapally A, Badar F, Ilsar I, Duvoisin N. Damages to the extracellular matrix in articular cartilage due to cryopreservation by microscopic magnetic resonance imaging and biochemistry. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farndale RW. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connective Tissue Research. 1982;9:247–248. doi: 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Templeton D. The Basis and Applicablity of the Dimethylmethylene Blue Bindings Assay for Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans. Connective Tissue Research. 1988;17:23–32. doi: 10.3109/03008208808992791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldberg RL, Kolibas LM. An improved method for determining proteoglycans synthesized by chondrocytes in culture. Connective Tissue Research. 1990;24(3–4):265–275. doi: 10.3109/03008209009152154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]