Americans have historically had perhaps the world’s most rigorous regulatory system for the protection of medical product consumers.1 FDA regulations have, however, become less restrictive in recent years.2 In particular, Congress and the FDA have become more permissive with respect to the distribution of journal articles about off-label uses by manufacturers.1 The change in regulations has been highly controversial and has led to intense debate regarding the benefits and risks of this practice. Because the FDA does not have the manpower to monitor this activity and other potential channels for possible inappropriate off-label promotion by industry, alternative means of regulation may be needed.

The History of FDA Regulations Regarding Off-Label Promotion

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) of 1938 gave the FDA the authority to regulate drug promotion by pharmaceutical companies. FDA regulations have attempted to strike a balance between giving physicians the freedom to use their best clinical judgment and preventing drug manufacturers from inappropriately influencing prescribing practices.2 Therefore, according to FDA regulations, physicians may prescribe drugs for off-label use, but drug manufacturers may not promote such uses.1,2 The FDA and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) share responsibility for the regulation of medical device advertising.3,4 The FTC substantially defers to FDA regulatory practices, especially when therapeutic claims are involved.5

FDA regulations aim to ensure that advertising and promotion practices are supported by evidence from clinical experience and are truthful, balanced, and not misleading.2 Regulations guiding pharmaceutical promotion can be found in 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 202.1. These regulations apply to advertisements in journals, newspapers, and magazines and other periodicals, as well as radio, television, and telephone broadcasts.6 The FDA also regulates drug information posted by pharmaceutical companies on the Internet and materials directly distributed to health care professionals and patients.2 FDA regulations specify that drug advertisements cannot omit material facts or overstate product claims; they must present a fair balance between disclosure of efficacy, side effects, contraindications, and warnings.6,7 The promotional piece or advertisement must also contain a summary of side effects and contraindications and provide convenient access to the labeling.6

FDA regulations do not directly prohibit the promotion of off-label uses, but two provisions achieve that effect indirectly.2 Pharmaceutical manufacturers are barred from introducing a drug into interstate commerce unless the FDA has approved the drug and its label.2 A second provision prohibits manufacturers from introducing misbranded drugs into interstate commerce.2 Misbranding is considered to occur if drug labeling contains information that describes unapproved uses or is misleading or insufficient to support safe use for approved indications.2 Materials are considered part of drug labeling when they are distributed by the manufacturer to describe the uses of the drug whether or not they are part of product labeling.2 FDA regulations state that instead of engaging in inappropriate promotion, pharmaceutical companies must submit safety and efficacy data and obtain FDA approval prior to marketing a new drug indication.7

The FDA Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA), however, introduced regulations that included a provision (Section 401) that allowed drug and device manufacturers to distribute scientific literature on off-label uses if certain requirements were met (Table 1).2,8 The regulations stated that articles could be distributed only if the off-label use discussed was included in a filed or soon-to-be-filed supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA).2 Companies also had to provide the FDA with advance copies of the materials to be disseminated.2 The articles had to be of high quality, as evidenced by peer review and other specifications.2 If a drug manufacturer was in compliance with all of the requirements, the FDA could not use this activity as proof of a company’s intent to inappropriately promote off-labl drug use.1 Section 401 therefore provided a “safe harbor” for manufacturers with respect to the distribution of journal articles concerning off-label uses.1

Table 1.

Conditions Under Which Information About the Off-Label Uses of Drugs May Be Disseminated

| Condition | FDAMA Section 401† | 2009 Guidance‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Drug approval | Information must concern a drug or device that has received FDA approval for some use. | Drug-approval status not mentioned. |

| Commitment to file a supplemental New Drug Application | Manufacturer must have submitted a supplemental New Drug Application for a proposed new use or completed required studies and certified that this application will be submitted within 6 months after initial dissemination (or within 36 months if supporting studies not yet completed); may request exemption from this requirement if studies are prohibitively expensive or unethical. | Not mentioned; companies [are] encouraged to seek approval for new uses of a drug. |

| Advance provision to the FDA | Manufacturer must submit copy of article and other safety and efficacy information concerning unapproved use 60 days before dissemination. | Not mentioned |

| Source of underlying clinical data | Information must not be derived from another manufacturer’s clinical research (unless [the] other manufacturer gives permission) and must be from “scientifically sound” clinical investigation. | Information should be based on adequate and well-controlled clinical investigations. |

| Accuracy | Information must not be false or misleading, must not involve inappropriate conclusions, and must not pose significant risk to public health if relied on. Company may need to include other safety and efficacy information to ensure objectivity and balance. | Information should be truthful and not misleading and should not pose a significant public health risk if relied on. |

| Provision of countervailing scientific findings | Information must be disseminated along with approved labeling and comprehensive bibliography of publications related to off-label use (including unfavorable studies) and other available information about risks of this use. | Information should be disseminated with approved labeling and comprehensive bibliography of publications related to off-label use, plus representative publications (if any) reaching conclusions regarding this use that are contrary or different. |

| Required disclosures | Must include prominent disclosure stating that use is not FDA-approved and identifying other products (if any) approved for that use. | Should include prominent disclosure statement regarding unapproved use that identifies study sponsors, discloses relevant financial interests, and mentions any known significant risks not discussed in the publication. |

| Presentation of journal article | Must provide entire, unabridged article or section of reference publication; no promotional materials may physically accompany it, and company representatives may not verbally promote the new use. | Should provide entire, unabridged article or reference. It should not be marked, highlighted, summarized, or characterized in any way. |

| Journal requirements | Information must be published in peer-reviewed scientific or medical journal (listed in Index Medicus) and must not have appeared in industry-funded special supplement or publication; unabridged reference texts may also be distributed (including non–peer-reviewed texts if specific unapproved use [is] not highlighted). | Information should be published by an organization with [an] editorial board that involves experts with demonstrated expertise in subject of article and objectively reviews proposed articles, adhering to standard peer-review procedures; organization should adhere to published conflict-of-interest policy; information should not have appeared in an industry-funded special supplement or publication. |

| Distribution | Distribution must be limited to health care practitioners, pharmacy benefit managers, issuers of health insurance, group health plans, and federal and state agencies (no distribution to consumers). | Information should be provided separately from promotional information; distribution should be limited to health care practitioners and entities such as pharmacy benefit managers, health insurers, and government agencies (no distribution to consumers). |

| Other avenues of dissemination | Manufacturers may still disseminate information about off-label uses in response to unsolicited requests from health care practitioners. | Manufacturers may still disseminate information about off-label uses in response to unsolicited requests from health care practitioners. |

FDA = Food and Drug Administration; FDAMA = FDA Modernization Act.

Data from the FDA and the Code of Federal Regulations.

Data from the FDA.

From Mello M, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. N Engl J Med 2009;360(15):1557–1566. © 2009, Massachusetts Medical Society.2

The legality of these restrictions in the FDAMA was later questioned in a series of important legal cases that challenged this Act on the grounds that it violated constitutional rights.2 It was argued that the regulatory power granted to the FDA by Congress cannot violate the First Amendment right of medical manufacturers to engage in commercial free speech.2 Washington Legal Foundation v. Friedman challenged FDA restrictions on reprint distribution on these grounds.2 In 1999, a federal district court ruled that the objective of the FDA could be met by requiring manufacturers to make clear disclosures regarding the nature of information on off-label uses rather than imposing the restrictions in the FDAMA.2 The FDAMA was subsequently allowed to expire in September 2006.2

On January 13, 2009, the FDA issued new guidance that changed the FDAMA regulations with respect to reprint distribution on off-label uses by manufacturers (see Table 1).2,18 The new guidelines allow companies to distribute peer-reviewed scientific articles and texts describing off-label uses, subject to the new regulations.9 However, the new policy is more permissive than the FDAMA, because companies are no longer required to submit advance copies to the FDA and are not restricted to the dissemination of journal articles on off-label uses for which they have filed or will file an sNDA.2 However, the new regulations are more restrictive, in that the safe harbor provision is no longer included in the updated guidance.10

Permitted Sources for Off-Label Information

Although the FDA prohibits the promotion of drugs and devices for off-label uses by companies, many other sources for this information are available. Permitted sources for off-label information are discussed below.

Compendia and drug information references. Compendia and drug information reference handbooks are published by organizations or companies that are independent from manufacturers. These references typically include information on both labeled and off-label uses.11 Medicare, Medicaid, and many private insurers will cover off-label drug uses if they are included in major compendia, such as the American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information (AHFS DI); the U.S. Pharmacopeia Drug Information (USP DI), and/or Drugdex.6,7,11 Listings in compendia can benefit manufacturers because the inclusion of their products in these sources can boost sales.11

Continuing medical education. The FDA has traditionally differentiated between scientific and educational activities that are industry-supported and those that are independent and non-promotional.7 Therefore, the FDA does not regulate the presentation of scientific information in continuing medical education (CME) programs.7 However, in order for a program to be exempt from regulation, it must not be subject to any financial or other influence by medical product companies.7 The FDA has issued a list of conditions that an educational activity must meet in order to be exempt from FDA regulation (Table 2).6

Table 2.

Factors Used by the FDA to Determine Independence

| Control of content: Has there been scripting or other actions by the supporting company designed to influence content? |

| Disclosure: Has funding for the program and any legal or business relationships between the company, providers, and presenters been disclosed, particularly for an off-label discussion? |

| Program focus: Is the educational discussion fair and balanced? Does the title accurately represent the presentation? |

| Provider’s sales or marketing activities: Are provider employees also producing marketing or promotional programs? |

| Provider’s demonstrated failure to meet standards: Does the provider have a history of biased programs? |

| Multiple presentations: Do repeated presentations serve the public health interest? |

| Audience selection: Is the audience generated by a sales or marketing department in order to achieve marketing goals? |

| Opportunities for discussion: Is an opportunity for meaningful discussion provided? |

| Dissemination: Does the supporting company distribute additional information after the activity (unless requested by the participant and then provided through an independent provider)? |

| Ancillary promotional activities: Are promotional activities occurring in the same room as the educational presentation? |

| Complaints: Have there been complaints about the sponsoring company by providers, faculty, or others? |

Modified from From Malone P, et al. (eds). Drug Information: A Guide for Pharmacists, 3rd ed, 2006. With permission from The McGraw-Hill Companies.6

The Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) is responsible for identifying, developing, and promoting standards for CME.12 The ACCME must approve CME programs and requires any real or perceived conflicts of interest to be disclosed by presenters.7,12 The ACCME has established a system for peer review as well as the review and accreditation of CME providers to ensure that they meet established standards.7,12 According to the 2007 ACCME annual report, 113,003 CME activities were conducted in the U.S., reaching more than eight million physicians.13

Journal articles. Drug and medical device companies conduct the clinical trials that are necessary to gain regulatory approval and then disseminate these data through marketing, advertising, and publication in the medical literature.11 Company researchers and independent investigators then continue to conduct clinical studies to determine new uses for marketed drugs and devices and submit those results for publication as well.6 Companies may freely distribute copies of these articles that discuss not yet approved product usages if FDA regulations are met (see Table 1).6

Medical and graduate education. FDA guidelines to determine independence apply to other forms of medical and graduate education besides CME. This distinction between independent and promotional, company-sponsored activities is particularly important because off-label uses are often discussed in educational programs.6 Although educational events may be considered independent, companies frequently recruit and train influential academic physician-speakers or key opinion leaders (KOLs) to present unaccredited educational talks to colleagues, called “lunch and learns” or “dinner talks.”11 The company might provide event organizers with a list of speakers to choose from.11 Companies may also provide unrestricted grants to academic medical center departments for Grand Rounds.11 A KOL might also appear as the author of publications or posters presented during a medical education program that discusses off-label uses.11 Because the FDA considers the opinions expressed by these leaders to be independent, these talks are not subject to regulation and may freely cover both labeled and unlabeled uses.11 The FDA, however, may require disclosures of significant financial relationships between program faculty and industry.6

Medical liaisons. The FDA permits companies to respond to unsolicited questions from health care professionals about off-label uses.2,7 Such inquiries are usually from physicians seeking evidence to support an off-label treatment.6 These inquiries must be handled by a department that is separate from sales and marketing, such as the company’s medical affairs division.2,9 Responses to these unsolicited inquiries must narrowly focus on the question and must be balanced and documented.2 The materials provided by the company in response to the question must be non-promotional and may include journal articles, formulary advice, or answers to questions posed through a sales representative.6 Medical affairs personnel may not send unsolicited materials or information or formulary advice that qualifies as pre-approval promotion (known as new product seeding).6

Sales representatives. Sales representatives are allowed to provide copies of peer-reviewed journal articles to health care professionals but are not permitted to use them to promote company products.6,9 If the physician has questions about off-label uses, the representative must refer the question to a medical liaison who is not part of sales and marketing.9 Referral of the off-label question is made by filling out a postcard or calling the company to request that a packet of information be sent to the physician.11 The packet may contain journal article reprints and a standardized letter that discusses published clinical research on an off-label use.11

Web sites. The convenience of the Internet for accessing information is an advantage to medical manufacturers, prescribing physicians, and patients.1 Full prescribing information for most approved drugs can be found on the Web.6 The information posted on company Web sites is limited in order to avoid regulatory problems.1 However, off-label data may be freely circulated by other Web sites that are not agents of the manufacturer.1

The FDA had reportedly been working on specific guidance regarding company-sponsored promotional activities for pharmaceuticals on the Internet but ceased doing so because the medium was changing very rapidly.6 The FDA reportedly opted to apply existing regulations regarding drug promotion and advertising to the Web.6 For example, the FDA advises that a drug’s black-box warning should appear prominently on a Web page with prescribing information, just as is required for printed media.6

Controversies Regarding the Distribution Of Off-Label Information

There are two completely divergent views regarding the dissemination of off-label information by manufacturers: the belief that it provides transparency regarding treatment choices versus the opinion that it presents a significant risk to public health and well-being.1 Various groups have assembled both in support of and against the new reprint policy.2 Pharmaceutical companies and patient advocacy groups have expressed support, whereas consumer organizations and health insurers have voiced objections.2

Other commentators have also voiced opposition to the new reprint policy, including Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), who stated: “As a result of this guidance, what the FDA once considered evidence of unlawful marketing or misbranding or adulteration of a drug or device, the Agency now seems to consider appropriate dissemination of information.”12 The Senator suggested that the new reprint policy is contradictory because it forbids unlawful off-label promotion of products, but “the intent of manufacturers in distributing such scientific literature would be [exactly] to encourage or ‘promote’ an unapproved use.”12

One of the most significant concerns expressed by opponents is that allowing the distribution of off-label reprints permits manufacturers to go directly to physicians with new uses when they might otherwise have conducted clinical trials to seek approval for them.8,12 The disincentive to conduct clinical trials may undermine the regulatory framework that Congress and the FDA have built to monitor the efficacy and risks of drugs to public health.2 The primary motivation for manufacturers to conduct clinical trials has been to successfully navigate the regulatory process so that a drug can later be promoted and advertised for a use.1 Bypassing the need to conduct clinical studies for new uses enables drug companies to save an enormous amount of time and money.1 Leniency with regard to off-label drug promotion may also discourage competing companies from conducting clinical research to enter an existing drug into a new therapeutic market.1 The lack of clinical trial testing may become common, especially with respect to medications used to treat small populations, such as patients with rare illnesses, putting them at particular risk.2

If the manufacturer was required to conduct clinical studies on off-label uses, it might find that the drug is ineffective, harmful, or both; this discovery could prevent health risks.1 Fenfluramine, an appetite suppressant approved for short-term use, was prescribed in combination with phentermine (“fen-phen”) for long-term weight loss.1 Thousands of people developed heart valve damage from this off-label use before the adverse effect was identified and fenfluramine was removed from the market.1 This incident is often cited as an example of undesirable consequences when drugs are used in an unapproved dosage regimen, for an unapproved purpose, and without evidence of safety.1 When the FDAMA was adopted, consumer groups complained that Section 401 provided “dangerously inadequate protection for the American public from the substantial risks of unknowingly being prescribed drugs for off-label uses.”1 Congress was accused of “shamelessly” ignoring the lesson learned from the fen-phen disaster and placing the economic well-being of special interests above the health and safety of the public.1

It is also feared that permissiveness with respect to the distribution of off-label information would encourage manufacturers to “game the system” by seeking FDA approval solely for the narrowest and easiest-to-prove uses.1 If the manufacturer knows that it can advertise the product for a variety of uses after the initial approval is granted, the firm might be unlikely to make its initial application to the FDA broader than necessary.1 Under these circumstances, a manufacturer might conduct only the minimum required number of clinical trials needed to gain initial approval for one basic use.1 The many other disease indications for which the drug might later be marketed off-label would not have been proven safe or effective.1

These concerns were directly addressed in the original FDAMA legislation, by the requirement that drug manufacturers must file an sNDA if they wished to distribute reprints regarding an off-label use.1 For these reasons, some commentators have called for the FDA to reinstitute the requirement that companies submit an sNDA in order to distribute off-label reprints.2 It has also been suggested that companies be required to conduct clinical trials for any off-label use that has become widespread.2 Although these might be good ideas, the results of prior legal challenges indicate that the courts would likely deem such conditions on commercial free speech unconstitutional.2

Arguments in Favor of the Distribution Of Off-Label Information

Although many controversies exist, experts generally agree that further efforts are needed to increase access to suitable off-label drugs for patients with rare and other diseases. However, they also concur that potential inappropriate promotion, as well as possibly dangerous prescribing practices for these drugs, should be prevented.14 In its guidance on the distribution of off-label reprints, the FDA also recognized the benefits of off-label information by acknowledging that such uses are important and even represent the recognized standard of care for some conditions.9 The FDA also recognized that public health might be advanced if health care professionals were to receive journal articles and references that are truthful and not misleading about unapproved uses.9

Proponents argue that the key benefit of allowing manufacturers to distribute off-label information is that it allows more data to be readily available to physicians, enabling them to make better treatment decisions.1,15 David B. Nash, MD, MBA, Dean of the Jefferson School of Population Health in Philadelphia, agreed, saying “all practitioners could benefit from transparency of information regarding the impact of off-label use.” However, Randy Vogenberg, RPh, PhD, Chief Strategic Officer of Employment-Based Pharmaceutical Strategies in Sharon, Massachusetts, and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Management at the University of Rhode Island in Kingston, Rhode Island, observed that off-label information is beneficial “only if it is appropriately utilized as an informational tool. Awareness remains an issue in many conditions for both patients and prescribers, but unfortunately, abuse and overpromotion continue too frequently.”

It is extremely difficult for a physician to independently keep current by reading all of the medical journals and compendia available.1 This challenge creates a high risk that an important study that might significantly impact treatment practices might be missed.1 Relaxing restrictions on the distribution of off-label reprints enables clinicians practicing in some of the most challenging areas of medicine—oncology, psychiatry, and pediatrics—to become more knowledgeable about treatment alternatives.16 A physician also sometimes has to make quick treatment decisions and cannot wait for information on an off-label use to be sent by a manufacturer.1 The distribution of high-quality, focused information on off-label uses by a manufacturer could therefore be seen as an important service.1 Dr. Vogenberg agrees, within limits:

Clinicians today have even less time with more information to digest. Depending on their practice area, this could be a valuable service if it is not abused. If publications are reputable and studies are reasonable at face value, then it’s probably safe to rely on the information, but this doesn’t mean not to follow the patients and their response to the off-label use of a medication.

Proponents also point out that allowing the distribution of off-label information supports innovation in clinical practice, which is particularly important when approved treatments have failed.17 Off-label drug use may be particularly beneficial to the 20 million Americans with “orphan diseases” who often rely on off-label drug uses for treatment.1,15 Orphan diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease) and cystic fibrosis, are defined by federal law as those that afflict fewer than 200,000 Americans.1 In some circumstances, a drug manufacturer may sponsor an orphan drug and may receive federal research grant funds and exclusive marketing rights for drugs approved to treat a rare disease.1 However, there is little other economic incentive for manufacturers to conduct expensive clinical trials for a drug used to treat such a small population.1 Dissemination of off-label information, therefore, can keep medical practitioners informed about the treatment options available for patients afflicted with these rare diseases.1

An additional important argument is that because the FDA approval process is so complex, costly, and time-consuming, the distribution of off-label drug information provides physicians and patients with early notification about novel treatments.1,17 Even with the advent of the fast-track approval process, the regulatory process is often considered to be unable to keep up with advances in medicine.1 The approval of an off-label use of rituximab (Rituxan) for cancer treatment reportedly took four years.10 Proponents also point out that some off-label treatments have already been validated by high-quality independent research conducted outside of the FDA regulatory process that indicates immense benefit to patients.17 Supporters contend that if patients had to wait for use-specific FDA approval to be alerted about off-label treatments, many would lose the opportunity to benefit from innovations that are continuously developed in clinical practice.17 For example, aspirin was widely prescribed to reduce the risk of heart attacks long before the FDA approved it for this purpose in 1998.5,18

Physicians have also been slow to modify their prescribing behaviors and even lag in adopting evidence-based practice guidelines issued by prestigious organizations.5 The dissemination of information through advertising or promotion has been shown to improve the adoption of products other than drugs.5 The timely delivery of information through promotion is also likely to be particularly valuable in updating physician treatment decisions because this knowledge can play a key role in keeping up with rapidly changing prescribing practices.5

Ironically, permitting off-label promotion may also benefit the FDA.1 A former counsel for the House Commerce Committee reportedly commented that the FDA was unnecessarily expending resources to monitor off-label drug use.1 Abandonment of this practice could allow these human and financial resources to be reallocated to accelerate new drug evaluation.1

Viewpoints Against the Distribution Of Off-Label Information

Opponents to the distribution of off-label information by manufacturers also have a number of compelling arguments. They warn that permitting this activity could expose the practice of medicine to vulnerabilities that exist in the published literature.2,19 They caution that peer review alone does not ensure that off-label information will be of a high quality.19 The risks they cite include these possibilities:2,19

strategic decisions made by pharmaceutical sponsors that might solely seek publication of positive trial results

misleading portrayal and interpretations of data in low-quality studies

suppression of data on safety risks

ghostwriting of journal articles sponsored by companies

the limited ability of the FDA and medical journals to detect these problems

Critics of the new off-label reprint guidance point to these issues, among others, as evidence that peer review is insufficient protection against corporate influence over the content of publications.2 With regard to whether the medical literature can be trusted to guide off-label use, Dr. Vogenberg stated:

The literature has always been plagued with problems, which is why multiple studies are generally required before adopting off-label use beyond those patients approved by a medical exception. Trust is based upon the person and organization represented, so it depends as much on the integrity of the messenger as much as the message.

There is also concern that busy physicians would not have the time to do their own due diligence regarding off-label uses and might rely solely on industry-distributed journal articles.2

Conversely, it has also been said that the quality of peer-reviewed literature would be degraded by allowing companies to support off-label uses by distributing journal article reprints.19 During the New Drug Application (NDA) process, the FDA staff supervises every phase of a trial and scrutinizes the resultant data. However, unless the sponsored study is part of an sNDA, the FDA is unlikely to have input into the choice of study design, outcome measures, or comparators.19 Editors and manuscript reviewers might not be familiar with critical details of clinical study design and conduct and could unwittingly publish poor-quality or biased data.19 They might not know how to evaluate biased adjudication of endpoints, concealed adverse effects, or unreported changes in primary outcomes.19 Medical journals could also be challenged if companies actively petition for favorable portrayal of their products in articles.2

Medical journal editors would also have no way of knowing whether an article from a seemingly independent author is truly objective or is company-sponsored and ghostwritten.19 One study estimated that 85 publications—up to 40% of the literature published on sertraline (Zoloft) between 1998 and 2000—had been company-sponsored through a single medical education and communications company.19 Concern about ghostwriting and manipulation of data has also been expressed by Senator Chuck Grassley who said: “I have serious concerns about [the] FDA’s guidance, in light of studies and editorials on ghostwriting and manipulation of data by the drug industry and my own findings regarding the lack of or limited transparency in the financial relationships between the drug and device industries and physicians.”12

ACCME officials have also acknowledged that even though they have instituted measures to ensure presenter independence and compliance with FDA regulations, violations may still occur. Murray Kopelow, MD, MS, FRCPC, Chief Executive of ACCME, stated:

There is a recurrent and repeated … set of noncompliance findings with some of the elements of our standards. … The most common noncompliance is failure of planning committee members to demonstrate that they have disclosed their financial relationships and resolved them. … Thirty or 40% of our providers … in … a small percentage, 10% or 20% of their activities, … can’t show that their planners have disclosed. … A rapid response improvement plan had to be put into place, so we identify a provider that is functioning non-independently, or [that] the content was biased, or there was failure to disclose or failure to resolve conflict of interest. … Our system [also] doesn’t address fraud. … These are professionals, and they are … believed when they do disclose. If they don’t tell the truth and they don’t tell everything, the accredited providers are not necessarily going to know.

Another, less obvious argument against off-label promotion addresses insurance and reimbursement hurdles.1 It might be difficult for physicians to sort out reimbursement intricacies for off-label drugs before prescribing them.14 Dr. Nash reflected: “Clearly reimbursement issues are so complicated, I think this all has to be interpreted on a case-by-case basis.”

As recently as a decade ago, most insurers, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and governmental plans refused to cover the cost of off-label medications on the grounds that such treatment was considered to be experimental, even though there was evidence for efficacy.1,14 Most states have since passed legislation prohibiting insurance companies from excluding coverage for off-label drug use in the treatment of certain ailments.1 However, the legislation governing insurance reimbursement for off-label uses varies from state to state.1 Some insurance companies have also conceded only to cover off-label uses listed in major compendia.1

However, the compendia are not always comprehensive with respect to off-label drug uses.1 The National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD) has therefore advocated that compendia include more clinical evidence-based information for the off-label treatment of rare diseases.14 Insurance carriers are also now being pressured by patients and advocacy groups to cover all off-label drug uses.1 The American Medical Association (AMA) has reportedly encouraged such coverage, stating:

When the prescription of a drug or use of a device represents safe and effective therapy, third-party payers should consider the intervention as reasonable and necessary medical care, irrespective of labeling, and should fulfill their obligation to their beneficiaries by covering such therapy.”1

Despite steps toward and support of off-label drug use, patients may still have to pay high treatment costs directly out of pocket for drugs and devices that their physician has been encouraged to use outside of labeling.1

Limitations in the Ability of the FDA to Regulate Off-Label Promotion

In theory, the FDA regulates off-label drug promotion; in practice, however, it is limited in this area.18 Congress has continually given new duties to the FDA without increasing its budget, which restricts the ability of the FDA to effectively regulate across all areas of responsibility.1 The FDA’s Division of Drug, Advertising, Marketing, and Communications (DDMAC) is primarily responsible for the oversight of drug promotion.7

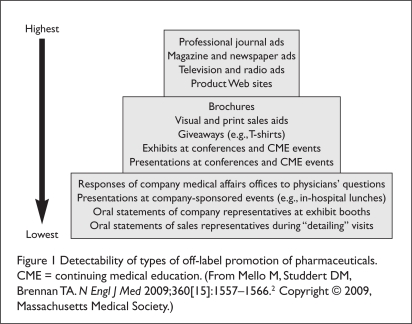

FDA officials acknowledge that it is difficult, if not impossible, for the monitoring and surveillance efforts it conducts to identify all off-label promotion that takes place.7 Inappropriate promotion can take many forms, occur in a multitude of places, and range in degree of visibility (Figure 1).2,7 The FDA is said to have chosen to focus attention on relatively visible activities because of its limited capabilities—tracking behavior that is publicly visible is easier and less expensive.2 Activities that are public may also be observed by watchdog groups, which may criticize the competence of the FDA if blatant violations are not identified and restrained.2

Figure 1.

Detectability of types of off-label promotion of pharmaceuticals. CME = continuing medical education. (From Mello M, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. N Engl J Med 2009;360[15]:1557–1566.2 Copyright © 2009, Massachusetts Medical Society.)

Perhaps the most easily observed forms of promotion are advertising and marketing activities (see Figure 1).2 According to FDA regulations, all promotional materials must be submitted to the FDA at the time of dissemination to the public.2 Companies may also submit these materials for “advisory review” before they are distributed.2 A company may opt to do this before launching an expensive full-scale advertising campaign or a costly television commercial.7 FDA officials consider advisory review to be particularly important because it encourages voluntary compliance.7 This process allows the FDA to identify potential violations, including off-label promotion, before materials are distributed.7 The FDA has therefore made it a priority to evaluate all voluntarily submitted draft materials for advisory review.7 As part of its comments, the FDA provides guidance to the drug company on how to address any agency concerns regarding the promotional materials.7

Potential means of inappropriate drug promotion that are moderately visible include brochures, posters, sales aids, giveaway items, and presentations made at conferences and CME events (see Figure 1).2 DDMAC and other FDA staff members are able to attend only a small number of the thousands of CME programs that occur each year.7 Responses by medical affairs personnel to unsolicited requests for drug information from health care professionals are also moderately visible and difficult to monitor, but this content is likely to be thoroughly reviewed by company compliance officers.2

The lowest tier of visible promotional practices is occupied by oral statements made by company representatives (see Figure 1).2 Because inappropriate oral communications are not documented and are delivered in private or semiprivate settings, they are very difficult for the FDA to track.2 It is therefore necessary to rely on reports from competitors, company whistleblowers, or physicians who are the recipients of inappropriate verbal off-label information.2,7

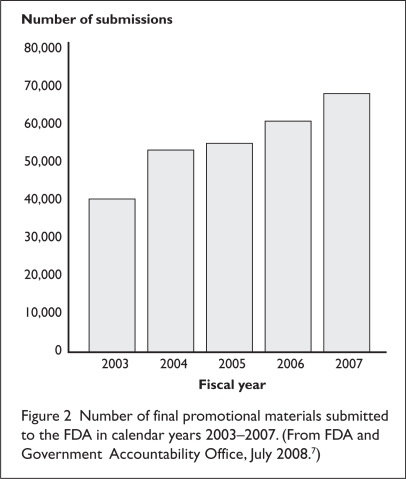

Despite the FDA’s goal to review all voluntary and final submissions of promotional information before distribution, the DDMAC is unable to do so because it is overwhelmed by the volume of materials it receives (Figure 2).7 As of 2008, the DDMAC division of the FDA had only 44 employees assigned to monitor marketing activities and prescription drug promotional materials.20 DDMAC officials admitted that although most of the drafts submitted for advisory comments are examined, the division can inspect only a small portion of the final materials submitted for review.7 The volume has steadily increased from just over 40,000 submissions in 2003 to over 68,000 in 2007 (see Figure 2).7 This growth is generally attributed to increases in direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising as well as to the generation of a greater number of materials by drug companies to promote complex new drugs.7 The DDMAC staff does not systematically prioritize all the final materials it receives but instead makes reviewing ads for prescription drug claims that might significantly affect human health the priority.7,20

Figure 2.

Number of final promotional materials submitted to the FDA in calendar years 2003–2007. (From FDA and Government Accountability Office, July 2008.7)

A report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) recognized that the FDA is challenged by the volume of materials it receives, therefore preventing a detailed review of each submission.7 The GAO observed that without a more systematic screening system, the ability of DDMAC to review the highest-priority materials or thoroughly identify all violative materials is uncertain.7 The GAO therefore recommended that the FDA systematically screen all submissions in order to determine which ones should be reviewed instead of selecting a subset according to the current criteria.7 The GAO also recommended that a tracking system be put in place to improve the FDA’s ability to identify promotional violations.7 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) officials reportedly replied to these conclusions by stating that the screening system currently used by the FDA is sufficient and that a tracking system would not improve the agency’s ability to identify promotional violations, nor would it change which submissions were reviewed.7 Despite these problems in the screening system, both the FDA and the GAO have acknowledged that the review process is critical to the agency’s ability to prevent or minimize dissemination of inappropriate materials.2

The GAO also reported that the FDA is limited in its monitoring and surveillance efforts to detect violations that might occur elsewhere.7 The Office concluded that the numerous places and ways promotional activities can occur make it difficult for FDA to comprehensively monitor them.7 The FDA’s monitoring and surveillance efforts are also complicated by difficulties in assessing the validity of the complaints it receives as well as in determining whether reports of potential violations have merit.7 For example, the FDA is not able to determine whether a speaker at a CME event has been paid by a company to promote an off-label use, thereby creating a conflict of interest.7 Therefore, when the FDA is limited in its authority to gather evidence, it may also work with other agencies, such as DHHS’ Office of the Inspector General (HHS–OIG) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), which have subpoena authority to enable a thorough investigation.7 As for the difficulty in validating complaints, if a physician reports to the FDA that off-label promotional material was shown during a sales visit, the agency will not likely be provided with that material and, therefore, might be unable to determine whether a violation occurred.7 DDMAC officials report that as part of their monitoring and surveillance efforts, they do consistently follow up on all complaints received, including those related to off-label promotion.7 From 2003 to 2007, the FDA received and investigated an average of 150 complaints annually.7 DDMAC officials have said that such complaints provide a backup system to the review of submitted materials for detecting violations.7

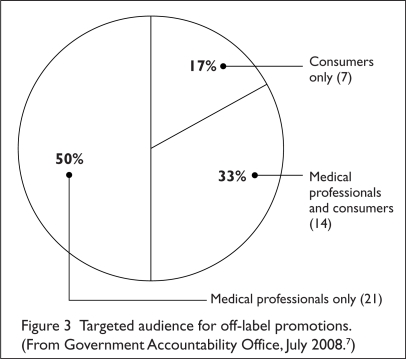

When a violation is definitively identified, the FDA can take action by issuing one of two types of regulatory letters:7 either an “untitled letter” or a “warning letter” (for more serious violations).7 Both types of letters cite the violation and ask the drug company to cease dissemination of any promotion with the same or similar claims.7 A warning letter goes a step further and requests that the company take action to correct the misleading impression that had been communicated.7 Such action may include notifying health professionals by issuing a correction in the same media in which the original violative promotion had appeared.7 During calendar years 2003 through 2007, 42 of the 117 regulatory letters (36%) issued by the FDA were in response to off-label promotion—19 untitled letters and 23 warning letters (Table 3).7 Off-label promotion was the third most common promotional violation identified during this period.7 Most off-label materials found to be in violation were directed at health care professionals (Figure 3).7

Table 3.

Frequency of Violations in 117 Regulatory Letters in Calendar Years 2003 to 2007

| Cited Violation | No. of Regulatory Letters | Percentage of Total Letters (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Omission or minimization of risk | 95 | 81 |

| Overstated effectiveness or unsubstantiated effectiveness claims | 54 | 46 |

| Off-label promotion | 42 | 36 |

| Unsubstantiated superiority or comparative claims | 40 | 34 |

| Failure to submit required material to the FDA | 18 | 15 |

| Other | 27 | 23 |

Percentages do not add to 100 because most letters cite more than one violation.

From Government Accountability Office, July 2008.7

Figure 3.

Targeted audience for off-label promotions. (From Government Accountability Office, July 2008.7)

The GAO also reported that there is a delay in the issuance of warning letters by the FDA that compromises their effectiveness.7 The FDA was found to have taken an average of seven months to issue these letters from the time they had first been drafted.7 It was also determined that the companies took an average of four months to take corrective action in response to the 23 warning letters that were issued for more serious violations.7,20

With regard to enforcement actions, the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 allows the FDA to impose civil monetary penalties against companies for false or misleading advertisements, including off-label promotion.7 If a drug company refuses to comply with a regulatory letter issued by the FDA, the agency may also refer the violation to the DOJ for seizure of the product and injunctions prohibiting the company from continuing with the off-label promotion.7 The DOJ may continue the investigation and can prosecute the company for violations identified by the FDA as well as for those reported by other sources.7 Enforcement actions may be brought by either federal or state prosecutors under the FFDCA, the Anti-Kickback Act, or the False Claims Act as well as state fraud statutes.2 The HHS–OIG has also been diligently pursuing off-label promotion as a form of Medicare fraud.21

According to DDMAC officials, no violations were referred to the DOJ for enforcement action during calendar years 2003 through 2007 because drug companies complied with FDA regulatory requests.7 However, during this time, the DOJ pursued a number of alleged off-label promotion violations that were identified by sources outside the FDA.7 DOJ enforcement actions resulted in 11 monetary settlements with drug companies ranging from nearly $10 million to more than $700 million.7 For example, in September 2007, Bristol-Myers Squibb agreed to pay in excess of $500 million for, among other things, the off-label promotion of aripiprazole (Abilify).7 The drug had been approved to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but it was suspected that the medication was being promoted for pediatric use and treatment of dementia-related psychosis.7 The DOJ alleged that Bristol-Myers Squibb had created a team of sales representatives to target nursing homes, where dementia is much more prevalent than schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.7 In recent years, there has also been a trend toward filing criminal as well as civil charges for offenses.2 Consequently, some prosecutions have also led to jail time for company executives as well.2

Alternative Means of Regulating Off-Label Promotion

Because the FDA may be limited in its ability to regulate off-label promotion, supplementary means of oversight may be necessary. A discussion of alternative means of regulation follows.

Industry Self-Regulation

The risk of intentionally or unintentionally violating FDA regulations is a constant source of worry for manufacturers; if such violations occur, the company may be exposed to negative publicity and enormous fines.22 Since 2003, the pharmaceutical industry has paid more than $5 billion in fines—money that could have paid for the development of four or five new drugs instead.22 To reduce potential risks, companies reportedly - requested that the FDA more accurately define the boundary between legal and illegal promotional activities, which they saw as unclear.22 This request was said to prompt the FDA to issue proposed guidance on reprint distribution in 2008 that was later finalized in 2009.2

Company compliance officers tend to focus on interactions between sales representatives and health care professionals, but there are many additional areas of risk.22 As many as 80 company exposure points for potential off-label drug promotion violations have been identified.22 Risk areas include speaker programs, advisory boards, formulary reviews, medical conferences, interactions with medical science liaisons, and publication of medical information through vendors.22 If processes that support compliance with regulations break down for these activities, they may be deemed to be inappropriate marketing by the FDA.22

In recent years, drug makers are said to have gone through a major metamorphosis to minimize exposure to off-label risks by hiring consultants and attorneys to retrain employees, rehabilitate processes, and automate systems.22 New standard operating procedures have been issued to address major risk areas.24 Widespread exposure to risks makes compliance with off-label regulations difficult to correct through policies and procedures alone.22 Drug makers, therefore, also use self-regulation and monitoring to identify issues before they become financial problems.22 It has been recommended that each activity and all possible departments, as well as outside vendors, be monitored.22 These efforts have reportedly added another $1 billion to the costs connected with off-label promotion.22 Dr. Nash observed:

I think the industry recognizes its responsibility in this area and has dramatically pulled back inappropriate advertising and inappropriate promotion in the past year. The industry recognizes and appreciates the feedback it has received from across the spectrum—Congress, practitioners, organized medicine—and has responded accordingly.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturing Association (PhRMA) has also issued a code governing appropriate interactions between industry and health care professionals. Guidance on informational presentations, professional meetings, consultant activities, scholarships, educational funds, and instructional and practice-related items is included.6 PhRMA has also recently issued revised “Principles on Conduct of Clinical Trials and Communication of Clinical Trial Results,” which take effect on October 1, 2009.6 These principles intend to “[increase] transparency in clinical trials, [enhance] standards for medical research authorship and [improve] disclosure to manage potential conflicts of interest in medical research.”23

Changes include the adoption of authorship standards that allow only individuals who make substantial contributions to the manuscript to be indicated as authors. Disclosure in medical journal manuscripts of financial relationships that might create a conflict of interest is also required.23 PhRMA also supports the revised Physician Payments Sunshine Act, which has been proposed in the Senate and accepts that “appropriate transparency in relationships with health care professionals can help build and maintain patient trust in the health care system.”3

Physician Self-Regulation and Monitoring

Physicians may also need to self-monitor their prescribing practices in order to avoid inappropriate off-label drug uses. They might consider a number of factors, including clinical data, whether they were influenced by promotional information from pharmaceutical companies, and any reimbursement hurdles that might exist before they decide to prescribe a medication for an off-label use.14 Such restraint not only protects patients from unsafe or ineffective off-label uses but also guards physicians against tort liability and medical malpractice suits.1 Problems may also arise when the treatment is considered experimental rather than off-label.6 For experimental uses, submission of an Investigational New Drug Application (INDA), an institutional review board (IRB) approval, or both, is required.6

The AMA is currently developing programs to educate physicians about inappropriate drug company promotions.7 The organization received financing for these programs as one of 28 recipients of grants funded by a settlement from a drug company for off-label drug promotion.7 It has also been suggested that such fines and settlements be used to reward health care professionals who report off-label promotion.11 Personal-injury lawsuits filed by patients against companies and physicians may also serve as a backup regulatory mechanism when off-label prescriptions have resulted in concrete harms.2

Independent Complaints from Whistleblowers

Private citizens will continue to play an important role in monitoring the off-label promotion of pharmaceuticals.2 Whistleblower, or Qui Tam litigation under the False Claims Act, is likely to continue to increase.2 Under this Act, company insiders and others with special knowledge of violations may initiate legal action.2 The government may then join or take over the action, and the whistleblower is allowed to keep a sizable portion of any resulting settlement or award.2

This “bounty system” is becoming well known and has proved to be a powerful incentive that has led to a wellspring of litigation under the False Claims Act.2 Company risks may increase as a firm dismisses large numbers of personnel in response to financial pressures in the current economic environment.2 This has the potential to create disgruntled former employees who may have insider knowledge of a company’s off-label promotional practices.2

Requirement for Clinical Trials on Widespread Off-Label Uses

Rather than forbid the promotion of off-label uses for medical products, an alternative approach might be to mandate manufacturer sponsorship of safety and efficacy trials for major off-label product uses.15 The FDA could be empowered by Congress to require manufacturers to conduct safety and efficacy trials for products that have an off-label use that exceeds a certain threshold.15,19 Because there is no requirement for physicians to indicate the intended use when they write a prescription, the extent of off-label drug use might be monitored by other means.15 Postmarketing surveillance information may be obtained from insurers, surveys of physicians and patients, and adverse-event reports filed with manufacturers and the FDA.15 Failure to conduct clinical trials could result in civil penalties that would require the manufacturer to surrender profits from the unapproved uses.15 Reinstitution of the sNDA requirement would also be effective.19

Sunshine Laws

The new reprint policy may have attracted the most attention, but it is only one new measure in the evolution of a wider regulatory landscape.2 The regulatory environment for off-label promotion is becoming stronger in several other areas and involves a growing number of participants and tactics.2 Congress and more states are considering adopting “Sunshine Laws” that require the disclosure of financial relationships between physicians and drug manufacturers.2 Such disclosure would allow any inappropriate relationships between health care professionals and manufacturers to be identified and targeted by state and federal prosecutors.2 Other federal and state bills have sought to restrict or ban gifts to physicians from manufacturers.2

State Licensure of Medical Sales Representatives

A number of states have adopted or are considering legislation requiring medical product sales representatives to be licensed. In early 2008, Washington D.C., became the first jurisdiction to require licensure of pharmaceutical sales representatives when the SafeRx Act was passed.11 This Act requires that drug representatives be held to a professional code of conduct, refrain from engaging in deceptive or misleading marketing, and participate in continuing education as a condition for license renewal.11

Editorial Vigilance

Medical journal editors might also take increased responsibility to ensure the value and quality of published clinical trial results.2 This can prevent poor-quality data, submitted under the guise of valid scientific discourse, from being published and used as tomorrow’s promotional tools.2

Evaluation of Off-Label Drug Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) recommends that off-label drug information undergo an evaluation process similar to that applied to material for indicated uses. The Society recommends that “before considering off-label use, supporting safety and efficacy evidence must be carefully evaluated and a risk–benefit determination made, especially when alternatives with FDA-approved labeling are available for the intended off-label use.”24 Dr. Vogenberg agrees that the “ongoing clinical review process that has been used in hospitals and managed care settings for years for existing or new medication products” should be used to evaluate off-label use. He adds:

Generally, pharmacy, along with a medical specialist, reviews the literature as well as talks with colleagues about the off-label use during a prior approval process or formulary consideration work. All available data and information would be collected, assessed, and analyzed in accordance with preserving safety of the patient population, followed by efficacy of the product for that use beyond the FDA-labeled indication.

Further ASHP recommendations on protocols, prescriber responsibilities, and the need for balance when evaluating clinical studies are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

ASHP Recommendations For the Evaluation of Off-Label Information

The following principles should guide the off-label use of medications:

|

ASHP = American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Data created from Tyler LS, Cole SW, May JR, et al. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008;65:1272–1283.24

Company communications or presentations to P&T committees at institutions, hospitals, managed care organizations, or pharmacy benefit management (PBM) organizations also provide an opportunity for off-label information to be introduced.22 P&T committees should ascertain whether the information was provided for marketing purposes or as a legitimate response to an inquiry.22

It is also recommended that manufacturers monitor information provided to P&T committees. Companies should review a sampling of formulary presentations to compare the material presented with the material requested in order to identify any possible improper disclosures.22 The inclusion of a product on formulary in a therapeutic category for which it is not approved following a company presentation may also be indicative of inappropriate representation of the product.22

Conclusion

The guidance issued early this year relating to the distribution of off-label reprints by medical manufacturers has intensified the debate regarding off-label promotion. The regulatory environment regarding this issue will likely continue to evolve, as it does for other areas of legislation. Although some might worry that this guidance represents greater leniency by the FDA concerning off-label promotion by medical manufacturers, other measures have been proposed or enacted that help strengthen the regulatory environment and make up for the shortfall in the resources of the FDA. Manufacturers have also accepted the need for regulation, monitoring, and evaluation and have issued guidelines for compliance. Ultimately, whether or not manufacturers should be permitted to distribute off-label information should be assessed according to a risk–benefit analysis, just as the clinical information itself is evaluated.

Footnotes

The author is a Consultant Medical Writer living in New Jersey.

Disclosure. The author has no financial or commercial relationships to report in regard to this article.

References

- 1.O’Reilly J, Dalal A. Off label or out of bounds? Prescriber and marketer liability for unapproved uses of FDA-approved drugs. Ann Health Law. 2003;12(2):295–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mello M, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. Shifting terrain in the regulation of off-label promotion of pharmaceuticals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1557–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle0807695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), news release PhRMA revised marketing code reinforces commitment to responsible interactions with healthcare professionals, July102008. Available at: www.phrma.org/news_room/press_releases/phrma_code_reinforces_commitment_to_responsible_interactions_with_healthcare_professionals Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 4.Autor DM, U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Medical Device Law: An Overview May1996. Available at: www.usdoj.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usam/title4/civ00110.htm Accessed May 31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calfee JE. The role of marketing in pharmaceutical research and development. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(Suppl 3):77–85. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200220003-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumore M. Legal aspects of drug information practice. In: Malone P, Kier K, Stanovich J, editors. Drug Information: A Guide for Pharmacists. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2006. p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Government Accountability Office (GAO) Prescription Drugs: FDA’s Oversight of the Promotion of Drugs for Off-Label Uses Washington, DC: GAO; July2008. Available at: www.gao.gov/new.items/d08835.pdf Accessed May 31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold M. FDA OKs distribution of journal articles on off-label uses. Medical Marketing & Media. Available at: www.mmm-online.com/FDA-OKs-distribution-of-journal-articles-on-off-label-uses/article/123914/. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 9.FDA Reprint Practices for Off Label Marketing, 2009. Available at: www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm125126.htm. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 10.Barlas S. New FDA guidance on off-label promotion falls short for everyone. P&T. 2009;34(3):122–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fugh-Berman A, Melnick D. Off-label promotion, on-target sales. PLoS Med. 2008;5(10):e210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hearing on Confirmation of Governor Kathleen Sebelius to be Secretary of Health and Human Services, April 2, 2009. Available at: http://finance.senate.gov/hearings/testimony/2009test/040209QFRs%20for%20SubmissionKS.pdf Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 13.Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Annual Report Data 2007, August 28, 2008. Available at: www.accme.org/dir_docs/doc_upload/207fa8e2-bdbe-47f8-9b65-52477f9faade_uploaddocument.pdf Accessed May 31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampton T. Experts weigh in on promotion, prescription of off-label drugs. JAMA. 2007;297(7):683–684. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehlman M. Off-label prescribing. The doctor will see you now. May, 2005. Available at: www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 16.Koroneos G. In defense of peer review: Waxman opponents argue for distribution of off-label info. Pharmaceutical Executive, Direct Marketing Edition. Dec 5, 2007. Available at: http://pharmexec.findpharma.com/pharmexec/News+Analysis/In-Defense-of-Peer-Review-Waxman-Opponents-Argue-f/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/477262?contextCategoryId=39871. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 17.Edersheim JG. Off-label prescribing. Psychiatric Times, April 14, 2009. Available at: www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1401983. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 18.Wilkes M, Johns M. Informed consent and shared decision-making: A requirement to disclose to patients off-label prescriptions. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psaty BM, Ray W. FDA guidance on off-label promotion and the state of the literature from sponsors. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1949–1951. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.FDA poorly equipped to enforce off-label prescription drug marketing rules, GAO report finds. The Medical News. 2008 Jul 29; Available at: www.news-medical.net/news/2008/07/29/40324.aspx. Accessed May 31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.A new policy on off-label promotion? Not entirely. Pharmaceutical Executive, February 19, 2008. Available at: http://blog.pharmexec.com/2008/02/19/a-new-policy-on-off-label-promotion-not-entirely Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 22.Eaton F, Scallon M. On the job off-label compliance. Pharmaceutical Executive, April 1, 2008. Available at: http://pharmexec.find-pharma.com/pharmexec/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=507986&sk=&date=&pageID=3. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 23.Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), news release Revised clinical trial principles reinforce PhRMA’s commitment to transparency and strengthen authorship standards, April 20, 2009. Available at: www.phrma.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&Itemid=119&id=1210. Accessed May 31, 2009.

- 24.Tyler LS, Cole SW, May JR, et al. ASHP guidelines on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee and the formulary system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1272–1283. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]