Abstract

The functions of adult stem cells and tumor suppressor genes are known to intersect. However, when and how tumor suppressors function in the lineages produced by adult stem cells is unknown. With a large population of stem cells that can be manipulated and studied in vivo, the freshwater planarian is an ideal system with which to investigate these questions. Here, we focus on the tumor suppressor p53, homologs of which have no known role in stem cell biology in any invertebrate examined thus far. Planaria have a single p53 family member, Smed-p53, which is predominantly expressed in newly made stem cell progeny. When Smed-p53 is targeted by RNAi, the stem cell population increases at the expense of progeny, resulting in hyper-proliferation. However, ultimately the stem cell population fails to self-renew. Our results suggest that prior to the vertebrates, an ancestral p53-like molecule already had functions in stem cell proliferation control and self-renewal.

Keywords: Stem cells, Tissue homeostasis, Regeneration, Cell proliferation, Tumor suppression, p53

INTRODUCTION

The p53 family of transcription factors consists of three genes in vertebrates and is one of the most important and most studied gene families in vertebrate biology. The first identified member of this family was p53, which is best known for its role as a tumor suppressor but also has functions in diverse cellular processes that include the DNA damage response, cell proliferation, senescence and apoptosis (Evan and Vousden, 2001; Ko and Prives, 1996; Suh et al., 2006; Toledo and Wahl, 2006; Yee and Vousden, 2005). The other vertebrate p53 family members, p63 and p73, also function in response to DNA damage and in apoptosis (Murray-Zmijewski et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2002), but have additional roles in stem cell self-renewal (p63) (Senoo et al., 2007), neuronal differentiation/survival (p73) (Pozniak et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2002), and even as oncogenes (by negatively regulating p53) (Deyoung and Ellisen, 2007; Li and Prives, 2007; Moll and Slade, 2004). Interestingly, the single p53-like genes in flies and C. elegans have retained function in response to DNA damage, yet do not function in tumor suppression, stem cell self-renewal or neuronal survival (Brodsky et al., 2000; Derry et al., 2001; Ollmann et al., 2000; Rong et al., 2002; Wells et al., 2006). Therefore, a long-standing question is whether the functions of the p53 family in tumor suppression and stem cell self-renewal are specific vertebrate innovations or were these functions present in an ancestral p53-like molecule?

In addition to diverse cellular functions, the p53 family also has an intricate evolutionary history (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material) (Nedelcu and Tan, 2007). For example, p63 and p73 contain an additional C-terminal sterile alpha motif (SAM domain), which p53 lacks. Because p53 family members in several invertebrates also have C-terminal SAM domains, the invertebrate-vertebrate ancestor is likely to have had a p53 family member with a SAM domain (Lu and Abrams, 2006; Nedelcu and Tan, 2007; Ou et al., 2007). Regardless of the SAM domains in p63 and p73, vertebrate p53, p63 and p73 are more closely related to each other than those from any invertebrates (see Fig. S1B in the supplementary material) (Lu and Abrams, 2006; Nedelcu and Tan, 2007). This means that vertebrates have duplicated the ancestral molecule at least twice and one of these paralogs (p53) then lost the SAM domain. Owing to these duplications, invertebrate p53-like genes are orthologous to all three vertebrate genes and do not have a 1:1 orthology with either vertebrate p53, p63 or p73. For example, fly p53 has no SAM domain and thus is called ‘p53’ even though it is equally related to vertebrate p53, p63 and p73 (Ollmann et al., 2000). Interestingly, Drosophila, C. elegans, Tribolium (beetle), flatworms (Lophotrochozoans), Ciona (chordate) and Nematostella (anemone) all have p53-like molecules without SAM domains, suggesting that independent loss of this domain is common (see Fig. S1A in the supplementary material) (Nedelcu and Tan, 2007; Pearson and Sánchez Alvarado, 2008).

In order to further understand how p53-like genes have changed function during evolution it is crucial to use an animal that is an outgroup to flies, C. elegans and vertebrates, such as the freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Planarians are in the Lophotrochozoan super-phylum and thus promise to lend a fresh view on the functional evolution of the p53 family. In addition, planarians offer several advantages in the study of gene function in adult animals. Asexual planarians are long-lived, perpetual adults, which reproduce by binary fission and subsequent regeneration of missing body parts (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2002). This biology allows the study of gene function in adults by RNAi without any concern for embryonic requirements (Newmark et al., 2003). The regenerative capacity and tissue turnover are provided by a large number of adult somatic stem cells (neoblasts), which can be manipulated and studied in vivo as an entire population (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2006). Because planarians have high levels of tissue turnover and constant adult stem cell divisions, it is expected that they have a need for both tumor suppression and stem cell self-renewal, and might share similar genetic mechanisms with vertebrates in that both processes involve p53 family members (p53 and p63).

Here, we show that planarians have a single p53 family member, which we have called Smed-p53 owing to its lack of a SAM domain. Furthermore, we observed that Smed-p53 expression was largely restricted to the newly made, postmitotic progeny of stem cells. When Smed-p53 was knocked down by RNAi, animals showed an increase in stem cell number and proliferation at the expense of daughter cell differentiation, consistent with Smed-p53 having tumor suppressor-like function in planarians. However, as the Smed-p53 phenotype progresses, we observed a terminal depletion of the stem cell population, which suggests that this molecule might also function similarly to vertebrate p63. Smed-p53 is the first invertebrate p53 family member shown to have a role in stem cell proliferation control, self-renewal and lineage specification. From this, we conclude that an ancestral p53 family member was already functioning in stem cell biology and proliferation control and that these functions were not vertebrate innovations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Exposure to gamma irradiation

The asexual clonal line CIW4 of S. mediterranea was maintained and used as described (Gurley et al., 2008; Reddien et al., 2005a). Planarians were exposed to 10, 20, 30 or 60 Gray (Gy) of gamma irradiation using a J. L. Shepherd and Associates model 30, 6000 Ci cesium-137 instrument at ∼6.0 Gy/minute (10 minutes).

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Immunostaining with anti-phosphohistone H3 (H3ser10p) was performed as previously reported and photographed using a Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 equipped with an AxioCam HRc (Reddien et al., 2005a). H3ser10p images were processed and quantified using ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Specimens were fixed and stained as described previously for whole-mount and fluorescent in situ hybridization (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000; Pearson, 2009; Reddien et al., 2005b). Specimens were imaged using a Zeiss LSM-5 Live or Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. All WISH experiments were performed, imaged and processed identically to allow direct comparison between experimental animals and controls.

Histology

Serial plastic sections (10 μm) were obtained from RNAi and WISH worms by brief dehydration in 100% ethanol, a rinse with 1:1 ethanol:immunobed, and direct immersion in 100% immunobed with catalyst. Sections were photographed using a Zeiss Axiovert at 10× magnification.

Flow cytometry

The dissociation of planarians, cellular labeling, and isolation of cells by FACS were performed as described previously (Reddien et al., 2005b), but using a Becton Dickinson FACSAria and without the use of Calcein. At least 10,000 cells from each population were collected and processed for in situ hybridizations as described (Reddien et al., 2005b). At least 2000 cells were scored for Fig. 1G.

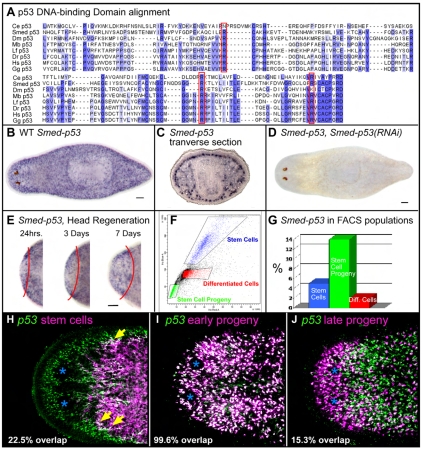

Fig. 1.

Sequence and expression pattern of Smed-p53. (A) Alignment of the DNA-binding domain of several p53 family members, with homologous residues shaded in blue. The three most commonly mutated residues in P53 in human cancers are framed in red. (B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for Smed-p53. All whole-mount staining patterns show dorsal views with anterior to the left. (C) WISH for Smed-p53, showing transverse section of worm at the axial level of the pharynx, dorsal is up. (D) WISH for Smed-p53 in a Smed-p53(RNAi) worm, 12 days after RNAi feedings. (E) WISH for Smed-p53 in an amputated worm growing a new head. Red line indicates amputation plane, new tissue (head) is to the left. (F) FACS profile of a dissociated wild-type planarian. Blue indicates the window enriched for stem cells, green indicates the window enriched for stem cell progeny, and red indicates differentiated cell types. (G) FACS-purified cell populations from F showing the relative percentage of cells in each population that express Smed-p53. (H-J) Double fluorescent WISH (FISH) for Smed-p53 and stem cells (H, smedwi-1), early progeny (I, Smed-NB21.11e), or late progeny (J, Smed-AGAT1). Blue asterisks indicate the position of the photoreceptors. Yellow arrows show double-positive cells. In this color scheme, double-positive cells appear white. For sequences used in alignment: Ce, C. elegans; Dm, Drosophila; Dr, zebrafish; Gg, chicken; Hs, human; Lf, squid; Mb, choanoflagellate; Smed, planaria. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Protein sequence analysis, alignments and protein prediction

SMED-P53 was found using the sequenced and assembled S. mediterranea genome with the use of BLAST. The Smed-p53 homolog was then found to exist as a full-length cDNA in a library (Sánchez Alvarado et al., 2002). Protein domains were predicted with the online tools SMART (Schultz et al., 1998) and InterProScan (Quevillon et al., 2005). T-Coffee was used for protein alignments (Notredame et al., 2000). The cDNA sequence and corresponding predicted protein can be found on NCBI. Ce, AAL28139; Smed, ACN51391; Dm, AAF40427; Dr, AAB40617; Gg, CAA31456; Hs, AAC12971; Lf, AAA98564; Mb, EDQ88915.

RNAi

cDNAs for individual genes were cloned into the pR244 vector and then expressed in the bacterial strain HT115 to make dsRNA as previously described (Reddien et al., 2005a) with optimizations (Gurley et al., 2008). Briefly, RNAi food is made by mixing a pellet of dsRNA-expressing bacteria from 30 ml of culture (OD600 of 0.8) with 300 μl of 70% liver paste. RNAi food is fed directly to worms every 3 days for three feedings. Hypomorphic levels of RNAi were delivered with a single feeding with amputation 2 days later. Live animals were photographed using a Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 equipped with an AxioCam HRc.

RESULTS

Planarians have a single p53 family member

In order to find p53 family members by homology, the ‘p53 DNA-binding domain’ is used because it is unique for this family of proteins (pfam 870). We used the DNA-binding domain to search the sequenced and assembled S. mediterranea genome (Cantarel et al., 2008; Robb et al., 2008). Exhaustive reciprocal BLAST and Hidden Markov Model searches revealed a single p53 family member. We cloned this predicted gene as a full-length cDNA from a planarian cDNA library, which also included a 23 bp 5′ UTR (Sánchez Alvarado et al., 2002). To check whether long N-terminal or C-terminal spliceoforms exist, we used 5′ and 3′ RACE and were only able to detect a single transcript containing a 42 bp 5′ UTR and a 298 bp 3′ UTR. The DNA-binding domain contains the three most frequently mutated residues in P53 (TP53) in human cancers (R175, R248, R273), which are also conserved in p63 and p73 (Kato et al., 2003; Li and Prives, 2007). Mutation at these three positions abolishes DNA binding and can create a dominant-negative protein (Chudnovsky et al., 2005; Li and Prives, 2007; Lozano, 2007). Interestingly, the predicted planarian protein is conserved at all three positions, whereas Drosophila and C. elegans are conserved at just two of the three positions (Fig. 1A).

The presence of a C-terminal SAM domain determines the naming of p53 homologs by distinguishing p63/p73 from p53. We searched for a SAM domain in the predicted planarian protein and also analyzed 40 kb of genomic DNA downstream of the 3′ end of the encoded transcript because it was possible that our cDNA did not include an exon coding for this domain. In all cases, our analyses failed to identify a SAM domain. To be consistent and to denote that the planarian p53 family member does not have a SAM domain, we have named this homolog Smed-p53, even though it is not a true ortholog of vertebrate p53 [as reported previously for other flatworm p53 homologs (Nedelcu and Tan, 2007)].

When we analyzed the sequence for SMED-P53, we found interesting differences in domain structure with vertebrate p53 family members. In addition to the p53 DNA-binding domain, vertebrate p53/p63/p73 contain four additional motifs. The N-terminus contains a transactivating (TA) domain and a proline-rich motif. The C-terminal region of vertebrate p53/p63/p73 contains a nuclear localization signal and an oligomerization domain. Although there was some homology in these domain regions, SMED-P53 lacked all four recognizable motifs, similar to Drosophila and C. elegans p53 (see Fig. S2 in the supplementary material). Therefore, SMED-P53 appeared most similar in domain structure to the p53-like genes analyzed in other invertebrates.

Smed-p53 is predominantly expressed in newly made stem cell progeny

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) of planarians showed Smed-p53 to be expressed in a discrete, cell-specific pattern similar to the spatial location of stem cells and their progeny (Fig. 1B). The transverse sections of animals stained for Smed-p53 showed strong subepithelial expression consistent with expression in stem cell progeny, and mesenchymal expression, consistent with expression in stem cells (Fig. 1C).

We confirmed that Smed-p53 was primarily restricted to newly made stem cell progeny using four methods. First, we followed the expression of Smed-p53 in regenerating head blastemas. During the first 3 days of head regeneration, stem cells remain in the old tissue while the regenerating head is populated by newly born, post-mitotic stem cell progeny (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Smed-p53 was expressed in the head blastema as early as 24 hours following amputation, suggesting that it was expressed in stem cell progeny (Fig. 1E).

Second, planarians can be exposed to gamma irradiation to specifically remove stem cells and their progeny in a kinetically stereotyped fashion, leaving other tissues unaffected (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Hayashi et al., 2006; Reddien et al., 2005b). In this paradigm, stem cells are depleted by 24 hours post-irradiation, whereas their transient ‘early’ progeny are depleted by 48 hours, and their ‘late’ progeny are depleted by 7 days (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Following irradiation, a slight decrease in Smed-p53 expression was detected by 24 hours, which is consistent with some expression in stem cells. However, most of the Smed-p53 expression was ablated 48 hours after irradiation, which suggested that Smed-p53 is primarily expressed in the early progeny (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material).

Third, stem cells and their progeny can be partially purified using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1F) (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Hayashi et al., 2006; Reddien et al., 2005b). Consistent with the observed WISH, in situ hybridization on sorted cell populations showed that the majority of Smed-p53 localized to stem cell progeny, with a smaller percentage of the expression in stem cells (Fig. 1G).

Lastly, because stem cells and their progeny are both molecularly and spatially distinct, we used double fluorescent WISH (FISH) with Smed-p53 riboprobe and either a stem cell marker (smedwi-1, Fig. 1H), an early stem cell progeny marker (Smed-NB21.11e, Fig. 1I), or a late stem cell progeny marker (Smed-AGAT1, Fig. 1J) (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). The majority of Smed-p53 expression was indeed specific to the newly formed progeny [99.6% (922/926 cells counted) of NB21.11e+ cells coexpressed Smed-p53], whereas a much smaller proportion of Smed-p53 expression was detected in the stem cells proper [22.5% (170/755) of smedwi-1+ cells coexpressed Smed-p53], with even less expression in late progeny [15.3% (126/825) of Smed-AGAT1+ cells coexpressed Smed-p53]. From the above expression data, we predicted that Smed-p53 functions very near the stem cell level of the lineage hierarchy, but most likely in the newly born, post-mitotic stem cell progeny.

Smed-p53(RNAi) causes stem cell-defective phenotypes during tissue homeostasis and regeneration

Feeding adult planarians with bacteria expressing dsRNA results in gene-specific knockdown that effectively spreads to all tissues in the organism (Newmark et al., 2003). Following RNAi feedings, WISH confirmed that Smed-p53 expression was efficiently eliminated during the proceeding 12 days (see Materials and methods; Fig. 1D). Uninjured Smed-p53(RNAi) worms exhibited a stereotypical ventral curling phenotype beginning around day 15, which proceeded until worms completely curled and lysed at about day 20 (100% penetrance; n=100; Fig. 2A). Ventral curling and lysis is a characteristic phenotype observed when stem cells are eliminated by a lethal dose of gamma irradiation (60 Gy, Fig. 2A), or when animals are subjected to RNAi for genes required for stem cell function (Guo et al., 2006; Reddien et al., 2005b). These data suggested that Smed-p53 was required for proper stem cell function and/or correct lineage production.

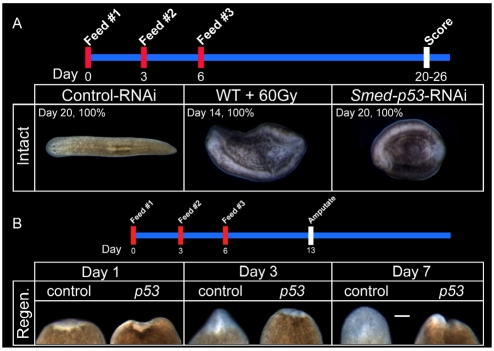

Fig. 2.

Smed-p53(RNAi) causes tissue homeostasis and regeneration defects. (A) Intact phenotype of Smed-p53(RNAi). The timeline for the experiment is shown across the top. First panel shows a dorsal view of a Control(RNAi) worm. Second panel shows a ventral view of a wild-type worm, 14 days after 60 Gy of irradiation, and the characteristic ventral curling phenotype which occurs when stem cells are lost. The third panel shows a ventral view of a Smed-p53(RNAi) worm 20 days post-RNAi feeding, which is consistent with a stem cell-defective phenotype. (B) The timeline for the experiment is shown across the top. Each panel shows a dorsal view of tail fragments regenerating a new head, with anterior up. Newly made tissue is relatively unpigmented. Worms are amputated 7 days after RNAi feeding, and their regeneration followed for the proceeding 7 days. As compared with Control(RNAi) worms, Smed-p53(RNAi) regeneration is severely deficient, indicating that Smed-p53 is required for proper stem cell function. Scale bars: 100 μm.

When Smed-p53(RNAi) animals were amputated into three fragments at 7 days post-RNAi, regeneration was severely impaired with minimal tissue produced (Fig. 2B). This phenotype was not dependent on which body part was regenerating because a head that was regenerating a new tail, or a tail that was regenerating a new head, or a trunk regenerating both a head and a tail, had similar defects (not shown). This is in direct contrast to amputated Control(RNAi) animals in which the resulting fragments completely regenerated the missing body parts in 7 days (Fig. 2B) (Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). Because stem cell function is essential to planarian regeneration (Reddien et al., 2005a; Reddien et al., 2005b), these data indicated that Smed-p53(RNAi) specifically disrupted planarian stem cell lineages. Nevertheless, the gross RNAi phenotypes lacked the necessary resolution to derive a mechanism explaining how the lineages had been impaired. It was equally possible that the defect in the lineage could be in the stem cells, stem cell progeny, or a combination of both, because disruption at any level of the lineage would give a gross stem cell defective phenotype. Therefore, we next analyzed proliferation, stem cells and their progeny during the course of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype.

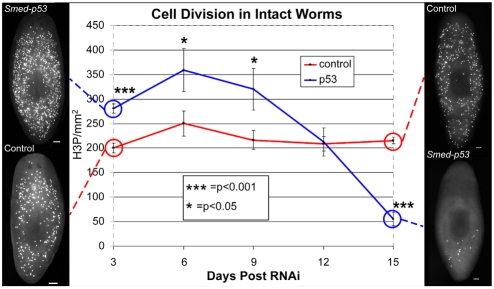

The Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype occurs in two phases: initial hyper-proliferation and terminal depletion

The fact that in vertebrates, p53 functions as a proliferation suppressor and p63 is required for stem cell self-renewal, suggested that the stem cell defective phenotypes of Smed-p53(RNAi) animals might be due to defects in cell division. If SMED-P53 is required only for stem cell self-renewal, we expected to observe immediate decreases in cell proliferation. Alternatively, if SMED-P53 were required to suppress cell division, we expected immediate hyper-proliferation. To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed whole-mount immunofluorescence for phosphorylated histone H3 (H3ser10p), which marks dividing cells beginning at the G2/M transition of the cell cycle. The experiments were performed following RNAi feedings, every 3 days for 15 days (Fig. 3). This time window immediately precedes the terminal (lethal) phenotype of ventral curling and lysis. Our results uncovered two phases of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype: (1) significantly increased cell division for the first 9 days (day 3; P<0.001); and (2) significant depletion of cell division by day 15 (P<0.001). Interestingly, when we performed a similar time course for regenerating fragments, we did not detect significant increases in cell division in Smed-p53(RNAi) animals above those normally observed after amputation in Control(RNAi) animals. This result suggests that the induced hyper-proliferation that occurs during regeneration is likely to be the highest level of proliferation that worms can achieve and thus might mask the effects of Smed-p53(RNAi) (see Fig. S4 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of cell division during the course of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype. Animals were stained following RNAi feeding, every 3 days for 15 days, using the marker H3ser10p, which marks cells during the G2/M transition of the cell cycle. Dorsal views with anterior to the top. Note the hyper-proliferation in Smed-p53(RNAi) worms during the first 9 days (blue line). Representative animals depicting this time point are shown on the left. Also note the loss of cell division at the latest time point of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype. Representative animals depicting this time point are shown at the right. Statistical differences are measured by Student's t-test and error bars indicate s.e.m. For each time point, n>20 with at least four experimental replicates. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Two hypotheses can explain the initial hyper-proliferation phase through perturbation of stem cells or their progeny. First, a scenario in which hyper-proliferation might be induced by failure of early progeny to differentiate, which then re-enter the cell cycle, in effect remaining stem cells. Second, that a failure of progeny to differentiate/survive might signal stem cells to increase cell division in order to compensate for lack of progeny. Examining changes in the lineage would distinguish between these possibilities. For both hypotheses, it was predicted that the early progeny would be affected, but if the stem cell population increased at the expense of progeny, it would suggest that SMED-P53 mediates a cell fate switch in the progeny to repress stem cell fate and proliferation. Alternatively, if stem cell and progeny markers were relatively normal, this would favor a feedback model in which inappropriately specified progeny signal the stem cells to increase proliferation (but not number). Therefore, we next examined changes in lineage markers during the initial phase of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype.

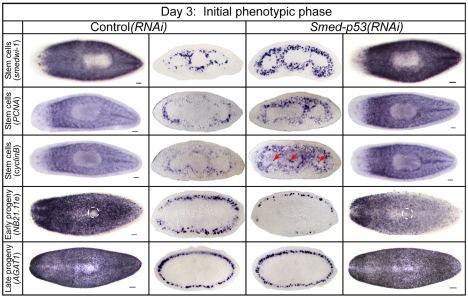

The initial hyper-proliferation phase is defined by a loss of early progeny with a concomitant increase in stem cell number and no detectable change in cell death

To determine which cell types were affected by the hyper-proliferation observed at day 3, we used recently identified lineage markers of planarian stem cells (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Briefly, it was found that a single BrdU pulse initially labels stem cells only, then chases into the early progeny, and then labels the late progeny, all cell types of which are in distinct spatial domains. The early progeny represent a transient, non-proliferative cell population that does not co-label with H3ser10p (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Although it remains unclear where the endpoint of this lineage is and how many total lineages exist in planarians, the direct lineage relationship using these three markers and cell types, i.e. stem cell (smedwi-1+) → early progeny (Smed-NB21.11e+, Smed-p53+) → late progeny (Smed-AGAT1+), has been demonstrated and is verified by our data (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Within the framework of this known lineage, we examined lineage production during the initial hyper-proliferation phase of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype.

Assay of the stem cell population at day 3 in Smed-p53(RNAi) animals by the expression of three stem cell-specific markers showed highly increased staining over controls (Fig. 4). Quantification in transverse sections of the stem cell-specific gene involved in proliferation, Smed-PCNA, showed a 39% increase in this cell population over controls (1686±68 versus 1212±65 cells/mm2; P<0.001). In addition, ectopic expression of the cell cycle gene Smed-cyclinB was also observed (Fig. 4, arrows). Conversely, assaying early progeny at day 3 by expression of the two markers Smed-NB21.11e and Smed-NB32.1g showed that these markers were dramatically decreased in Smed-p53(RNAi) animals, with decreases in staining in the dorsal population and little to no staining on the ventral side (Fig. 4 and see Fig. S5 in the supplementary material, respectively). The late progeny, as assayed by Smed-AGAT1 expression, appeared to be largely unaffected. This was not surprising because Smed-AGAT1 is not expressed in stem cell progeny until ∼3-4 days after their birth, and the Smed-AGAT1+ cell population does not disappear until 7 days after stem cells are ablated by irradiation and thus were not expected to be affected at this early time point, even though their precursor cells (NB21.11e+) were (Fig. 4) (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Finally, similar effects on stem cells and progeny were also observed for regeneration blastemas (see Fig. S5 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of stem cells and progeny during the initial phase (day 3) of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype. Whole-mount animals (the two outside columns) are shown dorsal side up with anterior to the left, with the exception of NB21.11e which are ventral side up and with the ventral opening to the digestive system circled (white dashed line). Cross-sections (the central two columns) for individual markers are shown with ventral side towards the bottom and at the same axial level to facilitate comparison across genotypes. At this time point, stem cell markers are increased, early progeny decreased, and late progeny unaffected. Red arrows indicate ectopic expression in gut branches, which was never observed in control animals. Scale bars: 100 μm.

The fact that the stem cell population increased at the expense of early progeny suggested that SMED-P53 might function as a cell fate switch when a cell transitions from immediate stem cell daughter to early progeny. However, it was also possible that SMED-P53 is simply required for early progeny survival. To test this hypothesis, we performed TUNEL stains at day 3 and saw no significant increase in cell death (see Fig. S6 in the supplementary material). Thus, the simplest explanation of the data was that SMED-P53 suppresses proliferation (and stem cell identity) and promotes differentiation in the early progeny. This hypothesis addresses the initial phase of the phenotype, but does not explain the loss of cell division at the late phase. Therefore, we next used the same lineage markers to describe the terminal phenotype.

The late phase phenotype shows that Smed-p53 is required for stem cell maintenance

In contrast to the hyper-proliferation observed at days 3-9, we observed a significant hypo-proliferation as the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype progressed to day 15 (Fig. 3; P<0.001). Using the above markers during this late phase of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype, we observed that there was a collapse of the entire stem cell lineage, in which animals lost their stem cells and progeny as if they had been irradiated (Fig. 5). Unlike during the initial phase (Fig. 4), there had been sufficient time to affect the late progeny markers by this time point (Fig. 5 and see Fig. S5, bottom row, in the supplementary material). Expression of the stem cell marker smedwi-1, as well as of the two cell cycle-specific genes Smed-PCNA and Smed-cyclinB, was virtually absent in both intact worms (Fig. 5) and regenerating fragments (not shown). Finally, FACS profiles of RNAi-treated worms showed similar decreases in dividing cells and stem cell progeny (see Fig. S7 in the supplementary material). These data were surprising because we expected the increase in cell proliferation and lack of differentiation to continue, with little disruption of the stem cells themselves. Thus, we next hypothesized that if we could bypass the late phase and terminal depletion of stem cells by delivering a lower dose of RNAi, we might be able to extend the hyper-proliferation phase, avoid depletion of the stem cell population, and study any resulting phenotypic consequences.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of stem cell lineage during the late phase (day 15) of the Smed-p53(RNAi) phenotype. Staining for the indicated cell lineage markers; dorsal views with anterior to the left. By day 15, when proliferation is observed to be depleted, stem cells, early progeny and late progeny are also depleted. Because the wild type has a higher cell turnover in the anterior-most cells (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008), we also observe corresponding anterior depletion when the stem cell lineage collapses. In most cases at this time point, staining for these markers in Smed-p53(RNAi) animals is undetectable. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Lower doses of Smed-p53(RNAi) uncover a role for Smed-p53 in radiation sensitivity and also cause tissue dysplasia during regeneration

Because the delivery of the standard amount of dsRNA for Smed-p53 led to 100% worm lethality, we reasoned that lowering the dosage might result in non-lethal phenotypes and could then also be useful to test for SMED-P53 interaction with known DNA damage response proteins identified in other model systems. In response to DNA damage, p53 is known to be phosphorylated by several evolutionarily conserved kinases in both flies and vertebrates (i.e. ATM, ATR, chk1, chk2) (Efeyan and Serrano, 2007; Sutcliffe and Brehm, 2004). We first cloned the planarian orthologs of these genes and fed a single dose of RNAi for Control, Smed-p53, Smed-ATM, Smed-ATR, Smed-chk1 and Smed-chk2, for which we observed no discernable phenotypes. However, various (10, 20 or 30 Gy) doses of gamma irradiation 2 days following RNAi for each of these genes showed a dramatic ability to modulate planarian survival curves (see Fig. S8 in the supplementary material). These results suggest that the ancestral function of the p53 family in the DNA damage response is also conserved for Smed-p53.

Previously, we observed that Smed-p53 was detectable by in situ hybridization for approximately the first 10 days following three feedings of RNAi, yet the hyper-proliferation phase of the phenotype occurred during this incomplete knockdown period, which indicated that an incomplete knockdown might be sufficient to trigger hyper-proliferation. We reasoned that a lower dose of dsRNA might extend the initial phase of the phenotype, in effect generating the RNAi equivalent of an allelic series. By lowering the dsRNA dose (one RNAi feed instead of three), we observed that intact worms showed no phenotype. However, we observed a new phenotype in regenerating head and tail fragments following amputation. By day 12 following a single RNAi feed, worms in this ‘hypomorphic’ state produced a visible outgrowth directly dorsal to the site where the new pharynx was being regenerated, and, intriguingly, as only heads and tails must regenerate a new pharynx, this suggested that the patterning and/or control over proliferation to regenerate this structure required Smed-p53 (Fig. 6).

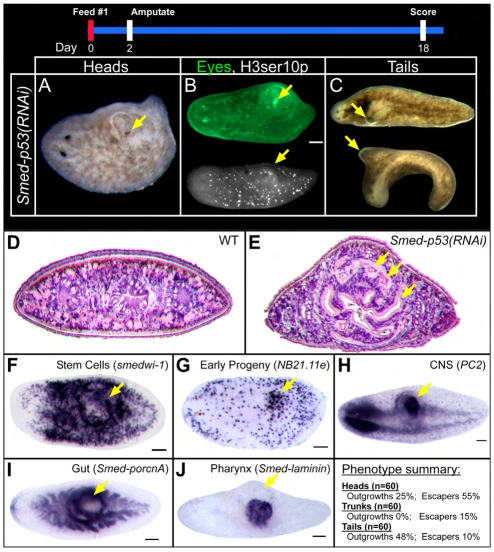

Fig. 6.

Smed-p53(RNAi) hypomorphic phenotypes. When planarians were fed lower levels of RNAi, head and tail (but not trunk) fragments developed a characteristic dorsal outgrowth directly above where a new pharynx is forming (see phenotype summary). (A) A head fragment is shown with a dorsal outgrowth that contains an ectopic eye (arrow). (B) The ectopic eye was also recognized as such by the eye-specific antibody VC-1 (green) and cell division was also seen in outgrowths by H3ser10p immunostaining. (C) The tail fragment above is a dorsal view, whereas that below is a lateral view with dorsal up. (D,E) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of transverse sections through the outgrowth showed dramatic disorganization compared with the wild type, particularly of the gut (arrows indicate ectopic gut branches). (F-J) Views are dorsolateral. In situ analysis confirmed that the outgrowth region contains (F) stem cells, (G) early progeny, (H) nervous tissue, (I) gut and (J) pharyngeal tissue. Arrows indicate outgrowth regions or ectopic tissue types. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Analysis of the abnormal dorsal outgrowth showed that it is solid and disorganized. Whereas wild-type worms have a single major pre-pharyngeal gut branch, Smed-p53(RNAi) hypomorphs had several disorganized gut branches (Fig. 6D,E,I). In addition, the dorsal outgrowth contained stem cells, early progeny, gut, nervous tissue and even ectopic eyes (Fig. 6B,F-J). Although animals that developed a dorsal outgrowth escaped ventral curling and lysis, the pharynx could not protrude out of the body to feed, and thus the animals eventually died from starvation after several months. This result suggested that the role of Smed-p53 in hyper-proliferation is different from that in stem cell maintenance because at low doses of dsRNA the stem cell population did not deplete, yet a structure associated with hyper-proliferation developed. Because the tissue in the dorsal outgrowth appeared disorganized, yet clearly contained multiple organ types, we hypothesized that this structure might be analogous to teratomas seen in vertebrates.

DISCUSSION

Evolution of the p53 family: similarity to vertebrate p53 and p63

Data from flies, C. elegans and vertebrates have made it widely accepted that p53 has acquired tumor suppressor function in vertebrates from an ancestral role of DNA damage sensing/repair (Sutcliffe and Brehm, 2004). However, there has never been a functional study of a p53 family member in an invertebrate that has a large population of adult stem cells, nor in an animal from the Lophotrochozoan super-phylum. The fact that vertebrates have three p53 family members that are duplicates in the vertebrate lineage leaves open the evolutionary possibility that the ancestral molecule had all the functions of p53, p63 and p73, which were then split up amongst the paralogs. The results presented here support this idea because the single planarian homolog of p53 has functions in stem cell lineages consistent with both tumor suppressor-like activity (vertebrate p53), and self-renewal (vertebrate p63). In future studies, it will be interesting to investigate whether SMED-P53 functions through mechanisms of target gene regulation that are similar to those of vertebrate p53 or p63.

Evolution of Smed-p53: differences with vertebrates

Following DNA damage in vertebrates, p53 transcriptionally induces the cell cycle inhibitor p21Cip1 (Cdkn1a). Therefore, we searched the planarian genome for p21 homologs and found none. Similarly, we could not find a p21 homolog in the genomic sequences of two other flatworm species. Thus, it was not possible to test whether SMED-P53 functions through a similar mechanism of p21 induction following irradiation or whether this reflects a real mechanistic difference. Although Drosophila has a clear p21 homolog, it is not induced by p53.

In vertebrates, p53 is post-translationally balanced by the negative regulators MDM2 and MDM4 (Toledo and Wahl, 2006). Any change in this delicate balance results in changes in p53 stability and function. Orthologs of Mdm2 and Mdm4 have not been described outside of the vertebrates. Similarly, planaria do not appear to have either of these genes. Therefore, we hypothesize that p53 did not acquire tumor suppressor function in the vertebrates, but rather that p53 acquired much tighter post-translational regulation. Additional support for this hypothesis is that p53 is very difficult to detect by in situ hybridization in vertebrates, but trivial to detect in planarians, suggesting that most of the regulation for Smed-p53 is at the transcriptional level.

In addition to MDM2/MDM4 regulation, vertebrate p53 has 187 known binding partners (Alfarano et al., 2005; Toledo and Wahl, 2006). Therefore, it is possible that p53 did not lose tumor suppressor function in flies and nematodes, but instead gained binding partners that together promote tumor suppressor function in planarians and vertebrates. A cursory search in the planarian genome for binding partners of vertebrate p53 that do not exist in the genomes of flies or C. elegans has uncovered potential differences (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). First, the known tumor suppressor and p53 binding partner BRCA2 exists in planaria and vertebrates, but not in flies or C. elegans (Jonkers et al., 2001). Additionally, only planarians and vertebrates have a DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNAPK, or PRKDC) gene, which is known to phosphorylate vertebrate p53 (Sheppard and Liu, 1999). Every additional p53 modifier or binding partner provides a potential mechanism for p53 to evolve a new function without changing its own sequence. Future studies will determine whether the conserved p53-binding proteins between vertebrates and planaria also have p53-like phenotypes in planarians.

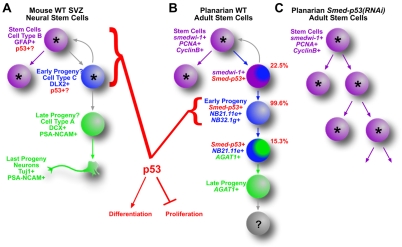

Studies in planarians can inform vertebrate hypotheses

Even though p53 is one of the most studied molecules in vertebrate biology, the exact mechanisms by which it exerts tumor suppressor function in stem cell lineages are unknown. For example, studies using knockout mice showed that neural stem cells lacking p53 (Trp53) had increased proliferation and possibly decreased differentiation (Gil-Perotin et al., 2006; Meletis et al., 2006). Nevertheless, where and how p53 might be functioning in these cells is not entirely clear because the precise in vivo lineage of mammalian neural stem cells was incomplete when these studies were performed (Fig. 7A) (Zhao et al., 2008). In fact, the lack of a precise lineage and the in vivo inaccessibility for most vertebrate stem cells limit our understanding of where and when p53 is expressed and what it does in those cells and how their lineages might change when p53 is removed. Based on our findings, we predict that the increased proliferation and concomitant loss of differentiation observed in p53–/– neural stem cells, for example, do not occur through changes in the stem cells proper, but by limiting proliferation and promoting differentiation in their newly made progeny. Given the rapid decrease in the numbers of early post-mitotic progeny observed in Smed-p53(RNAi) animals, it is possible that if a p53 mutation occurs in a stem cell, then the effect will be manifested in the progeny, which might now take on a stem cell-like fate (i.e. proliferative and less differentiated, Fig. 7B,C). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that planarians provide a model system with which to study tumor suppression and adult stem cell lineage development in vivo, and are likely to inform our current knowledge of adult stem cell function (tissue homeostasis and regeneration) and dysfunction (tumor formation and cancer).

Fig. 7.

Model of p53 function in mouse neural stem cell and planarian stem cell lineages. The known and unknown lineage relationships for mouse sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) neural stem cells and planarian adult stem cells. In mouse (A), precisely which cell types express p53 are unknown, although p53 functions somewhere near the top of the stem cell lineage to suppress proliferation and, most likely, to promote differentiation. In planarians (B), the lineage relationships of the cell types are known. Smed-p53 is expressed in all three cell types, also near the top of the stem cell lineage, but is primarily expressed in the early progeny. The data presented here show that this cell type is the first to be affected when Smed-p53 is lost, and that these cells lose their normal marker expression while at the same time a hyper-proliferation is observed, resulting in lineage model (C). Our data suggest that SMED-P53 has a tumor suppressor-like function in the early progeny, and in effect promotes the transition from a newly born daughter cell. In both systems, progeny feedback models (gray curved arrows) cannot be ruled out. Other gray arrows indicate inconclusive lineage relationships.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Gurley, J. Pellettieri, G. Eisenhoffer and S. Hutchinson for providing helpful comments on the manuscript. B.J.P. was funded by Damon Runyon Grant #1888-05. A.S.A. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.044297/-/DC1

References

- Alfarano C., Andrade C. E., Anthony K., Bahroos N., Bajec M., Bantoft K., Betel D., Bobechko B., Boutilier K., Burgess E., et al. (2005). The Biomolecular Interaction Network Database and related tools 2005 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D418-D424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky M. H., Nordstrom W., Tsang G., Kwan E., Rubin G. M., Abrams J. M. (2000). Drosophila p53 binds a damage response element at the reaper locus. Cell 101, 103-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel B. L., Korf I., Robb S. M., Parra G., Ross E., Moore B., Holt C., Sánchez Alvarado A., Yandell M. (2008). MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18, 188-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudnovsky Y., Adams A. E., Robbins P. B., Lin Q., Khavari P. A. (2005). Use of human tissue to assess the oncogenic activity of melanoma-associated mutations. Nat. Genet. 37, 745-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry W. B., Putzke A. P., Rothman J. H. (2001). Caenorhabditis elegans p53: role in apoptosis, meiosis, and stress resistance. Science 294, 591-595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyoung M. P., Ellisen L. W. (2007). p63 and p73 in human cancer: defining the network. Oncogene 26, 5169-5183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A., Serrano M. (2007). p53: guardian of the genome and policeman of the oncogenes. Cell Cycle 6, 1006-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer G. T., Kang H., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2008). Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell 3, 327-339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan G. I., Vousden K. H. (2001). Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer. Nature 411, 342-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Perotin S., Marin-Husstege M., Li J., Soriano-Navarro M., Zindy F., Roussel M. F., Garcia-Verdugo J. M., Casaccia-Bonnefil P. (2006). Loss of p53 induces changes in the behavior of subventricular zone cells: implication for the genesis of glial tumors. J. Neurosci. 26, 1107-1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Peters A. H., Newmark P. A. (2006). A bruno-like gene is required for stem cell maintenance in planarians. Dev. Cell 11, 159-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley K. A., Rink J. C., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2008). Beta-catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis. Science 319, 323-327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Asami M., Higuchi S., Shibata N., Agata K. (2006). Isolation of planarian X-ray-sensitive stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Dev. Growth Differ. 48, 371-380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J., Meuwissen R., van der Gulden H., Peterse H., van der Valk M., Berns A. (2001). Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 29, 418-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Han S. Y., Liu W., Otsuka K., Shibata H., Kanamaru R., Ishioka C. (2003). Understanding the function-structure and function-mutation relationships of p53 tumor suppressor protein by high-resolution missense mutation analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8424-8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko L. J., Prives C. (1996). p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 10, 1054-1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Prives C. (2007). Are interactions with p63 and p73 involved in mutant p53 gain of oncogenic function? Oncogene 26, 2220-2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G. (2007). The oncogenic roles of p53 mutants in mouse models. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 66-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. J., Abrams J. M. (2006). Lessons from p53 in non-mammalian models. Cell Death Differ. 13, 909-912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meletis K., Wirta V., Hede S. M., Nister M., Lundeberg J., Frisen J. (2006). p53 suppresses the self-renewal of adult neural stem cells. Development 133, 363-369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll U. M., Slade N. (2004). p63 and p73: roles in development and tumor formation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2, 371-386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Zmijewski F., Lane D. P., Bourdon J. C. (2006). p53/p63/p73 isoforms: an orchestra of isoforms to harmonise cell differentiation and response to stress. Cell Death Differ. 13, 962-972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu A. M., Tan C. (2007). Early diversification and complex evolutionary history of the p53 tumor suppressor gene family. Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 801-806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark P. A., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2000). Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev. Biol. 220, 142-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark P. A., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2002). Not your father's planarian: a classic model enters the era of functional genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 210-219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark P. A., Reddien P. W., Cebria F., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2003). Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100Suppl. 1, 11861-11865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. (2000). T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollmann M., Young L. M., Di Como C. J., Karim F., Belvin M., Robertson S., Whittaker K., Demsky M., Fisher W. W., Buchman A., et al. (2000). Drosophila p53 is a structural and functional homolog of the tumor suppressor p53. Cell 101, 91-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou H. D., Lohr F., Vogel V., Mantele W., Dotsch V. (2007). Structural evolution of C-terminal domains in the p53 family. EMBO J. 26, 3463-3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson B. J., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2008). Regeneration, stem cells, and the evolution of tumor suppression. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 73, 565-572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson B. J., Eisenhoffer G. T., Gurley K. A., Rink J. C., Miller D. E., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2009). A formaldehyde-based whole-mount in situ hybridization method for planarians. Dev. Dyn. 238, 443-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozniak C. D., Barnabe-Heider F., Rymar V. V., Lee A. F., Sadikot A. F., Miller F. D. (2002). p73 is required for survival and maintenance of CNS neurons. J. Neurosci. 22, 9800-9809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevillon E., Silventoinen V., Pillai S., Harte N., Mulder N., Apweiler R., Lopez R. (2005). InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W116-W120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P. W., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2004). Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 725-757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P. W., Bermange A. L., Murfitt K. J., Jennings J. R., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2005a). Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev. Cell 8, 635-649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P. W., Oviedo N. J., Jennings J. R., Jenkin J. C., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2005b). SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science 310, 1327-1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb S. M., Ross E., Sánchez Alvarado A. (2008). SmedGD: the Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D599-D606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y. S., Titen S. W., Xie H. B., Golic M. M., Bastiani M., Bandyopadhyay P., Olivera B. M., Brodsky M., Rubin G. M., Golic K. G. (2002). Targeted mutagenesis by homologous recombination in D. melanogaster. Genes Dev. 16, 1568-1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Alvarado A., Newmark P. A., Robb S. M., Juste R. (2002). The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development 129, 5659-5665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J., Milpetz F., Bork P., Ponting C. P. (1998). SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5857-5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M., Pinto F., Crum C. P., McKeon F. (2007). p63 Is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell 129, 523-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard H. M., Liu X. (1999). Phosphorylation by DNAPK inhibits the DNA-binding function of p53/T antigen complex in vitro. Anticancer Res. 19, 2079-2083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh E. K., Yang A., Kettenbach A., Bamberger C., Michaelis A. H., Zhu Z., Elvin J. A., Bronson R. T., Crum C. P., McKeon F. (2006). p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature 444, 624-628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe J. E., Brehm A. (2004). Of flies and men; p53, a tumour suppressor. FEBS Lett. 567, 86-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo F., Wahl G. M. (2006). Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 909-923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells B. S., Yoshida E., Johnston L. A. (2006). Compensatory proliferation in Drosophila imaginal discs requires Dronc-dependent p53 activity. Curr. Biol. 16, 1606-1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Kaghad M., Caput D., McKeon F. (2002). On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 18, 90-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee K. S., Vousden K. H. (2005). Complicating the complexity of p53. Carcinogenesis 26, 1317-1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Deng W., Gage F. H. (2008). Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell 132, 645-660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.