Abstract

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that link inflammation and cancer has significantly increased in recent years. Here, we analyse genetic evidence indicating that the transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) have a central role in this context by regulating distinct functions in cancer cells and surrounding non-tumorigenic cells. In immune cells, NF-κB induces the transcription of genes that encode pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can act in a paracrine manner on initiated cells. By contrast, in tumorigenic cells, both NF-κB and STAT3 control apoptosis, and STAT3 can also enhance proliferation. Consequently, inflammation should be considered as a valuable target for cancer prevention and therapy.

Keywords: inflammation, signal transduction, carcinogenesis, myeloid cells

See Glossary for abbreviations used in this article.

Glossary.

- CCL

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand

cylindromatosis

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

glycoprotein of 130 kDa

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- CXCL

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand

cylindromatosis

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

glycoprotein of 130 kDa

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- Cyld

cylindromatosis

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

glycoprotein of 130 kDa

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

glycoprotein of 130 kDa

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- gp130

glycoprotein of 130 kDa

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HIF1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HMGB1

high mobility group box 1

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cells

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IFN

interferon

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IκBα

inhibitor of κBα

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IKK

IκB kinase

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IL

interleukin

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- JAK

Janus kinase

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- JNK

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- mdr

multi-drug resistance

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- RANK

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- SOCS3

suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- SRC

sarcoma kinase

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor-α

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TLR2

Toll-like receptor 2

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TRAMP

transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Clinical and epidemiological studies have suggested a strong association between chronic infection, inflammation and cancer—an association that was initially proposed in the nineteenth century by Rudolf Virchow, when he noticed that a high number of leukocytes was present in tumour samples and suggested that tumours might be linked to chronic inflammation (Balkwill & Mantovani, 2001). The identification of infectious agents that cause cancer has recently led to the granting of several Nobel prizes, including those to Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren in 2005 for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, and Harald zur Hausen in 2008 for his discovery of human papillomaviruses that cause cervical cancer. Non-infectious agents—such as obesity, tobacco smoke, sustained alcohol abuse and inflammatory bowel disease (Aggarwal et al, 2009; Karin & Greten, 2005; Khasawneh et al, 2009)—can also cause chronic inflammation, thereby increasing the risk of cancer development. Importantly, an inflammatory microenvironment is an essential component of every tumour, including those that are not initiated by chronic inflammation (Mantovani et al, 2008). Over the past 10 years, genetic studies using cell-specific knockout animals have helped to start to unravel the molecular mechanisms that link inflammation and cancer. These studies have led to the idea that the tumour microenvironment is as important as the tumour cell population and, therefore, an inflammatory microenvironment has been suggested as the seventh hallmark of cancer (Mantovani, 2009).

The development of cancer can be divided into three distinct steps: initiation, promotion and progression (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2000). During the initiation step, cells acquire mutations that lead to the inactivation of tumour suppressor genes and/or the activation of oncogenes, thereby providing mutant cells with a growth and survival advantage. However, these initial mutations are not sufficient for full neoplastic progression; tumour promotion and progression depend on signals that originate from non-mutant cells in the tumour microenvironment. The tumour microenvironment is comprised not only of tumour cells, but also of stromal cells (such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells), cells from the innate immune system (macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, dendritic cells and natural killer (NK) cells) and the adaptive immune cells, T and B lymphocytes. These cell types secrete cytokines, growth factors, proteases and other bioactive molecules, which can act in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner and generate a delicate balance between anti-tumour immunity—which is provided by the adaptive immune system—and tumour-promoting immune activity, which originates from the innate immune compartment. During tumorigenesis, the host-mediated anti-tumour activity is thought to be suppressed and, therefore, pro-inflammatory actions prevail that ultimately support tumour growth, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (de Visser et al, 2006).

The direction in which the balance is tipped—either towards tumour suppression or progression—depends partly on the cell types and partly on the cytokine profile that is predominantly expressed in the tumour microenvironment. Tumour-associated macrophages (TAM) and T cells are the immune cells most commonly found in tumours, and several tumour types are characterized by a poor outcome when infiltrated by a high number of macrophages (Murdoch et al, 2008). Therefore, TAMs are generally considered to promote tumour growth and to be necessary for invasion, migration and metastasis (Condeelis & Pollard, 2006). By contrast, a high number of T cells correlates with better survival in colon cancer patients (Galon et al, 2006), although T cells can have both tumour suppressive and promoting effects (Sidebar A; DeNardo et al, 2009; Smyth et al, 2006). Importantly, it is not the relative abundance of each cell type but rather their respective activation and polarization profile—which is shaped by the cytokines that are present in the tumour microenvironment—that determines whether the effect will be to suppress or promote tumour growth. Several cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, IFNγ, TGFβ and TRAIL, are responsible for this polarization and are predominantly secreted by the respectively activated cells. In this context, IL-12, TRAIL and IFNγ are associated with cytotoxic T-helper 1 responses that mediate anti-tumour immunity, whereas TNFα, IL-6 and IL-17 suppress such polarization and promote tumour growth (Lin & Karin, 2007). Indeed, the tumour-promoting role of IL-17 was recently demonstrated in the B16 melanoma model (Wang et al, 2009) and in an intestinal tumour model (Wu et al, 2009).

Sidebar A | In need of answers.

Which signalling pathways promote tumour growth in immune cells and tumour cells?

Do T cells have different roles in different tumours?

What role do NF-κB and STAT3 have during tumour initiation?

Which is the best strategy to induce an anti-tumour response: targeting specific cytokines or targeting signalling pathways?

Can anti-inflammatory therapeutics be successful as single agents?

Is it reasonable to use anti-inflammatory therapies in combination with cytotoxic therapies to suppress therapy-induced inflammation, or does it prevent tumour-suppressive responses?

Which is the best way to prevent the immune-suppressive effects of IKK/NF-κB inhibitors? Should they be combined with TNFα or IL-1β inhibitors?

The characterization of the molecular mechanisms by which different cell types in the tumour microenvironment interact and communicate, and the identification of signalling pathways within these cells that ultimately promote tumour growth or suppress anti-tumour immunity remain a significant challenge (Sidebar A). An exact understanding of these complex interactions could help to find new targets for cancer treatment and prevention. Some of the underlying molecular mechanisms have been functionally elucidated using genetic knockout mouse models, which have shown that many of the cytokine-induced signalling pathways converge on two transcription factors: NF-κB and STAT3.

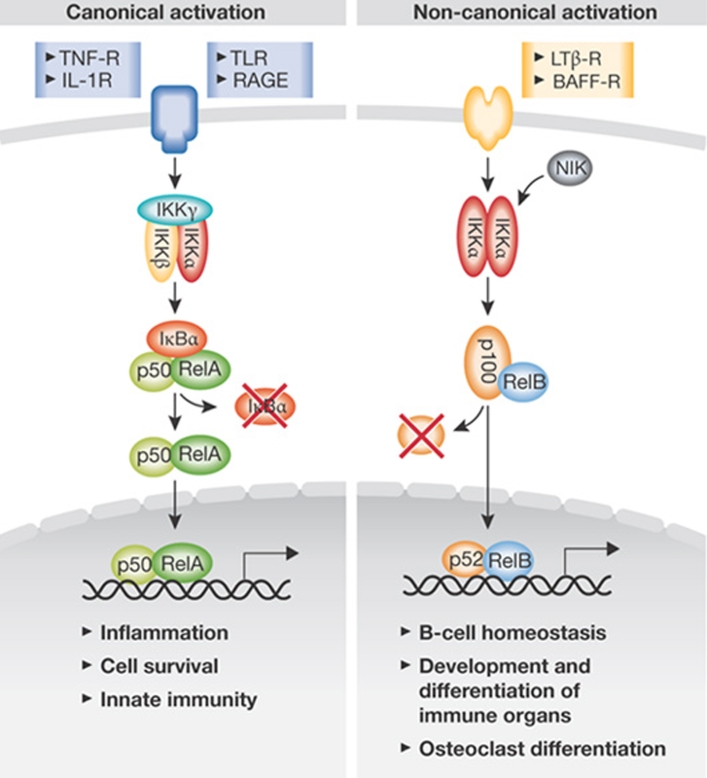

NF-κB and STAT signalling pathways

NF-κB is formed by homodimerization or heterodimerization of its five family members and is activated in response to several endogenous and exogenous ligands, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), TNFα and IL-1 (Vallabhapurapu & Karin, 2009). On engagement of the respective receptors, signalling impinges on a common molecular target, the IKK complex, which comprises two catalytic subunits—IKKα and IKKβ—as well as the regulatory subunit IKKγ. The canonical NF-κB activation depends on IKKγ and IKKβ kinase activity and leads to phosphorylation of the inhibitory protein IκBα, which is bound to NF-κB dimers in unstimulated cells. Phosphorylated IκBs are polyubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the proteasome, thereby allowing NF-κBs—which are mostly comprised of RelA:p50 heterodimers—to translocate to the nucleus and to exert their function as transcriptional regulators. By contrast, the non-canonical NF-κB activation is dependent on IKKα, but not IKKβ, and induces the processing of NF-κB2/p100:RelB dimers (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

NF-κB signalling. On ligand interaction with surface receptors, one of two NF-κB activation pathways can be elicited. Canonical signalling depends on IKKγ and IKKβ and induces the transcription of genes that regulate inflammation and cell survival. By contrast, non-canonical NF-κB activation is mostly involved in the regulation of B-cell development. BAFF, B-cell activating factor of the TNF family; IL, interleukin; IKK, IκB kinase; LTβ-R, lymphotoxin-β receptor; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end product; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

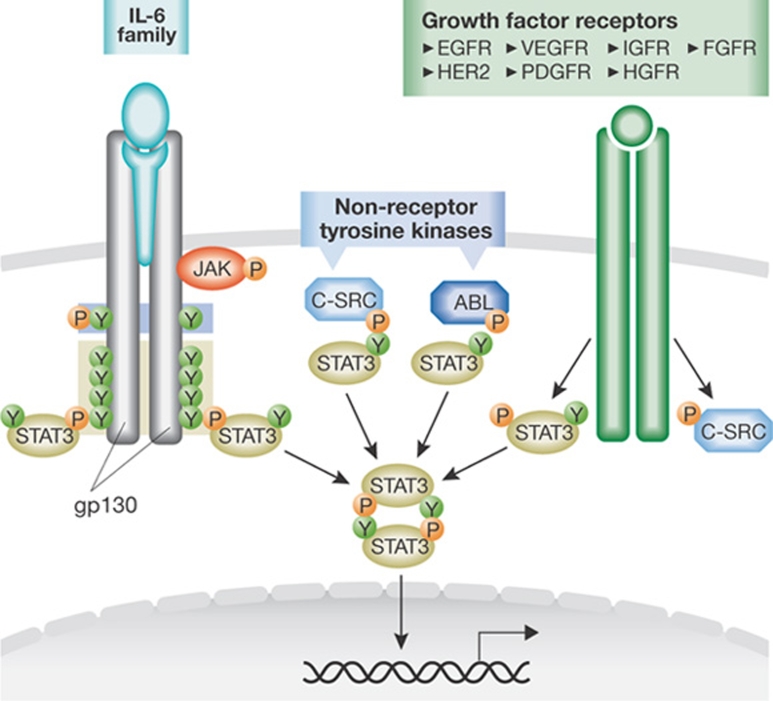

The engagement of the STAT3 pathway can be triggered by receptor tyrosine kinases—after the binding of members of the IL-6 or IL-10 protein families and certain growth factors to their receptors—as well as by non-receptor tyrosine kinases (Yu & Jove, 2004). The binding of growth factors or cytokines to their receptors results in the activation of their intrinsic receptor tyrosine kinase activity or of receptor-associated tyrosine kinases, such as JAK or SRC, that subsequently phosphorylate the cytoplasmic part of the receptor and provide docking sites for monomeric STATs. Once recruited, the STATs are phosphorylated on specific tyrosine residues, thus allowing their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

STAT signalling. On binding of IL-6 or IL-11 to the α-subunit of their receptors—which is followed by receptor heterodimerization with the gp130 receptor—JAKs are activated and phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic region of gp130, which lead to the recruitment of SHP2, STAT3 or STAT1 monomers. These STATs can bind to gp130 through their SH2 domains and become phosphorylated before their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus. Growth factors and non-receptor tyrosine kinases—such as SRC and ABL—can also activate STAT3 signalling. Growth factor receptors that are known to activate STAT3 include the epidermal growth factor receptors EGFR and HER2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR), insulin-like growth factor (IGFR), hepatocyte growth factor (HGFR) and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR). ABL, Abelson leukaemia protein; gp130, glycoprotein of 130 kDa; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; SRC, sarcoma kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

NF-κB and STAT3 in tumour promotion

Although NF-κB and STAT3 signalling pathways are persistently activated in various malignancies, as yet, no activating mutations have been found in the genes encoding these transcription factors in solid tumours. Instead, mutations occur either in upstream receptors, such as gp130—the activation of which results in STAT3 hyperactivation in liver tumours (Rebouissou et al, 2009)—or in genes encoding negative regulators of STAT3 signalling, such as SOCS3 in lung cancer (He et al, 2003). However, the most common mechanism by which NF-κB and STAT3 transcriptional programmes are induced is not through the mutation of proteins in their pathways, but by an excess of activating cytokines provided in an autocrine or paracrine manner.

Genetic and pharmacological manipulation of NF-κB and STAT3 activation in mouse models of colitis-associated cancer (CAC) and liver cancer has revealed the complex interplay of these signalling cascades in different cell types and that tumour cell intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulate apoptosis and proliferation. Although just 1% of all colorectal cancer cases occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, these patients represent one of the groups at highest risk of developing colorectal cancer. Furthermore, longstanding chronic colitis can increase the cumulative risk of developing colorectal cancer to almost 20% after 30 years (Eaden et al, 2001).

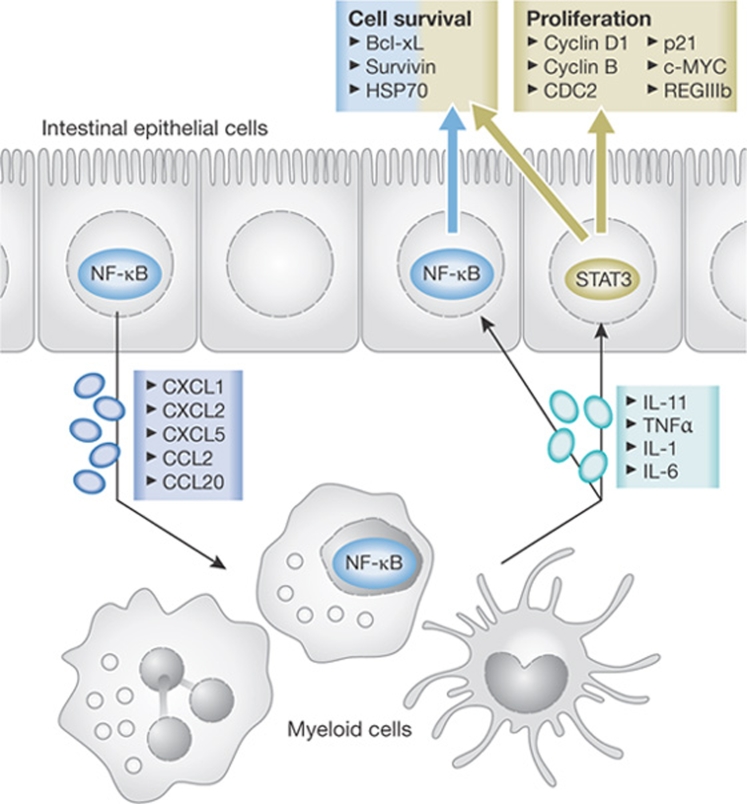

The first evidence of NF-κB having a direct and indirect role in tumorigenesis came from the CAC model through the deletion of IKKβ in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs)—which are the cells that undergo malignant progression—or the inhibition of NF-κB signalling in myeloid cells (Greten et al, 2004). In IECs, NF-κB regulates cell survival during early tumour promotion—and, therefore, tumour incidence—in a direct manner. By contrast, in myeloid cells, NF-κB induces the transcription of genes that encode pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-6, that can act on mutant cells to affect tumour incidence and tumour size through the paracrine induction of NF-κB and STAT3. Consistent with such an idea, Cyld-deficient mice exhibit an increased susceptibility to CAC, and an increase in TNFα and IL-6 secretion from stimulated macrophages (Zhang et al, 2006). Cyld is a deubiquitinating enzyme that presumably limits NF-κB activity by inducing the proteolysis of IKKγ (Sun, 2008). Subsequent studies in the CAC model confirmed the importance of TNFα signalling in bone-marrow-derived cells (Popivanova et al, 2008). Although there is evidence that immune cells are the main source of TNFα, autocrine production by cancer cells can also contribute to its secretion, particularly when NF-κB is activated within the cancer cells. As IEC-specific Ikkβ ablation did not affect mutant cell proliferation, it was suggested that the IL-6 released by either myeloid cells or T lymphocytes (Becker et al, 2004) would promote epithelial proliferation through the activation of STAT3. Indeed, the deletion of Il6 and the IEC-restricted deletion of Stat3 both suppressed CAC development (Bollrath et al, 2009; Grivennikov et al, 2009). The loss of STAT3 was particularly effective in blocking tumorigenesis and led to a growth arrest of premalignant lesions, almost abrogating the development of advanced tumours. Conversely, the introduction of a mutant gp130 receptor that induces STAT3 hyperactivation—or an IEC-specific deletion of the STAT3 feedback inhibitor socs3—stimulates proliferation and increases tumour multiplicity (Bollrath et al, 2009; Rigby et al, 2007). In line with a pro-proliferative function of STAT3 in the gastrointestinal tract, gp130 mutant mice spontaneously developed gastric cancer, which is dependent on IL-11 and not IL-6 (Ernst et al, 2008; Tebbutt et al, 2002). However, during CAC development, STAT3 not only controls proliferation but also affects epithelial cell survival, which might explain why the IEC-specific deletion of stat3 has a more profound effect on colitis-associated tumorigenesis than does the loss of Ikkβ in the same cells. Interestingly, the expression of chemokines induced by NF-κB in IEC is essential for STAT3 activation in epithelial cells during acute colitis (Eckmann et al, 2008). Thus, NF-κB controls STAT3 activation in IEC in a dual manner: by recruiting myeloid cells that secrete STAT3 activating cytokines and by controlling the transcription of these cytokines in myeloid cells (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

IEC–myeloid cell cross-talk during colitis-associated cancer. NF-κB-regulated chemokine expression leads to the recruitment of immune cells that secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-11 and the IKK/NF-κB-controlled TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6. These cytokines in turn induce STAT3 and NF-κB signalling in enterocytes. STAT3 controls the transcription of genes involved in both cell survival and proliferation, whereas NF-κB does not have an effect on proliferation. CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CXCL, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; HSP, heat shock protein; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; IL, interleukin; IKK, IκB kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; REG, regenerating islet-derived; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-α.

Mechanisms and cross-talk between tumours and immune cells in models of liver carcinogenesis have been described as similar to those in colon cancer. Liver cancer is the fifth most common type of cancer in the world, with a poor prognosis of a five-year survival rate of 9% (Sherman, 2005). The conditions that are associated with the development of liver cancer in humans include chronic hepatitis of viral or non-viral aetiology and the subsequent development of liver cirrhosis. These conditions establish a milieu of chronic inflammation that leads to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In the diethyl nitrosamine (DEN)-induced model of HCC, the inhibition of NF-κB in hepatocytes increases tumour incidence (Maeda et al, 2005). The increased hepatocyte damage that occurs in response to DEN causes an enhanced accumulation of ROS that prolongs the activation of JNK in the absence of NF-κB. This increased injury stimulates a stronger compensatory proliferative response and therefore increased cancer development. The NF-κB-dependent transcription of IL-6 in resident liver macrophages, known as Kupffer cells, has been considered to be at least partly responsible for the compensatory hyperproliferation of mutant hepatocytes. Accordingly, the loss of Il6 inhibited DEN-initiated proliferation and HCC development, which was associated with a diminished activation of STAT3 in hepatocytes (Naugler et al, 2007). Interestingly, mice with a hepatocyte-specific deletion of Ikkγ develop spontaneous steatohepatitis and HCC within one year (Luedde et al, 2007). In unchallenged knockout mice devoid of IKKγ in hepatocytes, HCC formation is dependent on ROS accumulation, similarly to DEN-treated mice with a hepatocyte-specific deletion of IKKβ. In both genotypes, compensatory hyperproliferation is inhibited when mice are treated with an antioxidant. The difference between these two mouse strains and the fact that animals with a hepatocyte-restricted loss of IKKβ do not develop spontaneous liver damage could, in part, be explained by the more complete inhibition of NF-κB in hepatocyte-specific IKKγ-deficient mice, or by as yet unidentified NF-κB-independent functions of IKKγ. The requirement for NF-κB-mediated tumour cell survival was also documented using mdr2−/− mice, which are a damage-independent model of liver tumorigenesis (Pikarsky et al, 2004) and develop spontaneous cholestatic hepatitis and subsequent HCC. Inhibition of NF-κB at late stages in this model reduced tumour size, which could be explained by an NF-κB-mediated prevention of hepatocyte apoptosis.

Collectively, these animal models illustrate the importance of cytokines and cell–cell communication during the promotion stage of carcinogenesis. They also highlight the essential role of NF-κB in controlling apoptosis in transformed cells—IEC and hepatocytes—and in inducing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines in bystander cells (myeloid cells), thereby activating the STAT3 pathway, which can mediate both cell survival and proliferation of mutant cells.

Inflammatory circuits that affect tumour progression

Inflammation is one prerequisite for tumour cells to invade and seed at distant sites, where inflammatory mechanisms will probably further support their engraftment and growth (Joyce & Pollard, 2009). Angiogenesis and EMT are important steps in tumour progression (Polyak & Weinberg, 2009), and genes necessary for angiogenesis are direct targets of NF-κB and/or STAT3—including VEGF, HIF1α, CXCL1 and CXCL8—and key molecules in EMT such as E-cadherin, Twist and Snail (Huang, 2007; Naugler & Karin, 2008). Furthermore, the expression of MMP2 and MMP9—which are essential for tumour cell invasion—is controlled by NF-κB and STAT3. Tumour necrosis and intrinsic signalling events lead to the recruitment of bone-marrow-derived cells and the secretion of cytokines and chemokines that favour tumour progression. IL-1α and HMGB1, which are capable of activating NF-κB in inflammatory cells and thereby induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Sakurai et al, 2008; Vakkila & Lotze, 2004), are typically released by dying tumour cells. In addition to immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have an important role during tumour progression, as they can be a main source of IL-6, VEGF, TGFβ (Spaeth et al, 2009) and the pro-invasive factors MMP3 and IL-8, the latter of which is released in a TNFα/NF-κB-dependent manner (Mueller et al, 2007). CAFs have been shown to exhibit robust IκBα phosphorylation and NF-κB activation in human colorectal liver metastases (Konstantinopoulos et al, 2007). Another mechanism by which cancer cells create a pro-metastatic environment is the secretion of extracellular proteins. For example, lung cancer cells secrete high amounts of versican, which induces TNFα and IL-6 production in myeloid cells through its binding to TLR2. The blockade of TNFα synthesis through the deletion of Tlr2 or Tnfa markedly suppresses the metastatic growth of versican-producing tumour cells (Kim et al, 2009).

Further genetic evidence linking the IKK complex to metastasis comes from a mouse model of prostate cancer (Luo et al, 2007). Although it only has a minor effect on primary tumour growth, IKKα represses the expression of the metastasis suppressor gene maspin in TRAMP mice. However, when IKKα activation is genetically inhibited, maspin expression is enhanced and metastasis is suppressed. Interestingly, IKKα-mediated maspin repression does not require NF-κB. In tumour cells, however, IKKα is activated by the RANK ligand, which is presumably secreted by tumour-infiltrating inflammatory cells—probably myeloid or T cells—and the expression of which is probably controlled by NF-κB and STAT3 (Leibbrandt & Penninger, 2008).

Is inflammation a target for cancer therapy?

For decades, tumour therapies have concentrated on cytotoxic regimens aimed at killing tumour cells directly. The advent of angiogenesis inhibitors pioneered the use of indirect approaches: inhibitors that target the tumour microenvironment to restrict the blood supply that tumour cells need to expand. A better understanding of the molecular changes that occur in the tumour microenvironment and their importance during tumour development paved the way for strategies that target specific cytokines, such as TNFα or IL-6, or the recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as CXCR4 and CCL2 inhibitors. Several phase I and phase II trials are now evaluating the safety and efficacy of these approaches in different malignancies (Garber, 2009). Whether these drugs will be successful as single agents is yet to be determined. In combination with cytotoxic drugs and/or irradiation, anti-inflammatory drugs can suppress therapy-induced tumour-promoting inflammatory processes and might, therefore, represent a more attractive strategy (Sidebar A). However, such efforts might also affect certain tumour-suppressive responses (Zitvogel et al, 2008).

Instead of inhibiting cytokines and chemokines, targeting the central regulators IKK/NF-κB and STAT3 seems to be a good alternative. In this respect, the additional pleiotropic effects of STAT3 in immune cells should be taken into consideration, such as the regulation of IL-23 and IL-17 (Kortylewski et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2009), its capacity to suppress immune surveillance (Yu et al, 2007) and the fact that both STAT3 and NF-κB inhibition would enhance sensitivity to cytotoxic drugs by enhancing apoptosis. However, there is one caveat to the potential of NF-κB and STAT3 as drug targets: the unwarranted effects that the long-term suppression of the STAT3 and/or NF-κB pathways would have on the immune system. Besides affecting the development of B and T cells (Vallabhapurapu & Karin, 2009), prolonged inhibition of IKKβ leads to an enhanced release of IL-1β during bacterial infections, possibly rendering patients particularly suspectible to the development of septic shock (Greten et al, 2007). Furthermore, STAT3 is an important factor in T-cell migration (Verma et al, 2009) and its blockade could have undesirable effects on the anti-tumour immune response. The development of specific delivery methods and the use of selective compounds might help to limit such side effects.

Several IKK/NF-κB or STAT3 inhibitors have been developed and provided promising results in pre-clinical models (Baud & Karin, 2009; Groner et al, 2008). Specific IKKβ inhibitors demonstrated great efficacy in lymphoid malignancies, such as multiple myeloma and a subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and could therefore represent invaluable novel therapeutics (Baud & Karin, 2009); however, their potential to treat solid tumours is yet to be clarified. Specific inhibitors of STAT3 include anti-sense oligonucleotides, peptides, peptidomimetics, small-molecule inhibitors and platinum complexes. One such small-molecule inhibitor, STA-21, prevents STAT3 dimerization and DNA binding, and inhibited the growth of breast cancer cells (Song et al, 2005). A platinum compound, IS3 295, selectively inhibited STAT3 signalling in various human and mouse tumour cell lines and induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Turkson et al, 2005). Furthermore, the small-molecule inhibitor S3I-M2001, which selectively disrupts active Stat3:Stat3 dimers, led to growth inhibition of breast cancer xenografts (Siddiquee et al, 2007). However, it will be exciting to see how well these specific inhibitors perform in the clinic and whether they will be superior to targeting single cytokines and chemokines in terms of efficacy and side effects.

Acknowledgments

Work in the laboratory of F.R.G. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, Association for International Cancer Research and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung.

References

- Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV, Sung B (2009) Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res 15: 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A (2001) Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357: 539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud V, Karin M (2009) Is NF-κB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8: 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C et al. (2004) TGF-β suppresses tumor progression in colon cancer by inhibition of IL-6 trans-signaling. Immunity 21: 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollrath J et al. (2009) gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 15: 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J, Pollard JW (2006) Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell 124: 263–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM (2006) Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 24–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo DG et al. (2009) CD4+ T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell 16: 91–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF (2001) The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 48: 526–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann L et al. (2008) Opposing functions of IKKβ during acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15058–15063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M et al. (2008) STAT3 and STAT1 mediate IL-11-dependent and inflammation-associated gastric tumorigenesis in gp130 receptor mutant mice. J Clin Invest 118: 1727–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J et al. (2006) Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 313: 1960–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber K (2009) First results for agents targeting cancer-related inflammation. J Natl Cancer Inst 101: 1110–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR et al. (2004) IKKβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 118: 285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR et al. (2007) NF-κB is a negative regulator of IL-1β secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKβ. Cell 130: 918–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S et al. (2009) IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell 15: 103–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groner B, Lucks P, Borghouts C (2008) The function of Stat3 in tumor cells and their microenvironment. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19: 341–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100: 57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B et al. (2003) SOCS-3 is frequently silenced by hypermethylation and suppresses cell growth in human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 14133–14138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S (2007) Regulation of metastases by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway: clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 13: 1362–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JA, Pollard JW (2009) Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 239–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Greten FR (2005) NF-κB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasawneh J et al. (2009) Inflammation and mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation link obesity to early tumor promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3354–3359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S et al. (2009) Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature 457: 102–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinopoulos PA et al. (2007) EGF-R is expressed and AP-1 and NF-κB are activated in stromal myofibroblasts surrounding colon adenocarcinomas paralleling expression of COX2 and VEGF. Cell Oncol 29: 477–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortylewski M et al. (2009) Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 15: 114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt A, Penninger JM (2008) RANK/RANKL: regulators of immune responses and bone physiology. Ann NY Acad Sci 1143: 123–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WW, Karin M (2007) A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest 117: 1175–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedde T et al. (2007) Deletion of NEMO/IKKγ in liver parenchymal cells causes steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 11: 119–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JL et al. (2007) Nuclear cytokine-activated IKKα controls prostate cancer metastasis by repressing Maspin. Nature 446: 690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S et al. (2005) IKKβ couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell 121: 977–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A (2009) Cancer: inflaming metastasis. Nature 457: 36–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F (2008) Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454: 436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller L et al. (2007) Stromal fibroblasts in colorectal liver metastases originate from resident fibroblasts and generate an inflammatory microenvironment. Am J Pathol 171: 1608–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE (2008) The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 618–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE et al. (2007) Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 317: 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Karin M (2008) NF-κB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikarsky E et al. (2004) NF-κB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 431: 461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Weinberg RA (2009) Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popivanova BK et al. (2008) Blocking TNF-α in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest 118: 560–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebouissou S et al. (2009) Frequent in-frame somatic deletions activate gp130 in inflammatory hepatocellular tumours. Nature 457: 200–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby RJ et al. (2007) Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) limits damage-induced crypt hyper-proliferation and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis in the colon. Oncogene 26: 4833–4841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T et al. (2008) Hepatocyte necrosis induced by oxidative stress and IL-1 alpha release mediate carcinogen-induced compensatory proliferation and liver tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 14: 156–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M (2005) Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, and screening. Semin Liver Dis 25: 143–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiquee K et al. (2007) Selective chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7391–7396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth MJ, Dunn GP, Schreiber RD (2006) Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: the roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Adv Immunol 90: 1–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Wang R, Wang S, Lin J (2005) A low-molecular-weight compound discovered through virtual database screening inhibits Stat3 function in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 4700–4705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaeth EL et al. (2009) Mesenchymal stem cell transition to tumor-associated fibroblasts contributes to fibrovascular network expansion and tumor progression. PLoS One 4: e4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SC (2008) Deubiquitylation and regulation of the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 501–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbutt NC et al. (2002) Reciprocal regulation of gastrointestinal homeostasis by SHP2 and STAT-mediated trefoil gene activation in gp130 mutant mice. Nat Med 8: 1089–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkson J et al. (2005) A novel platinum compound inhibits constitutive Stat3 signaling and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of malignant cells. J Biol Chem 280: 32979–32988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakkila J, Lotze MT (2004) Inflammation and necrosis promote tumour growth. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M (2009) Regulation and function of NF-κB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 693–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma NK et al. (2009) STAT3-stathmin interactions control microtubule dynamics in migrating T-cells. J Biol Chem 284: 12349–12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L et al. (2009) IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med 206: 1457–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S et al. (2009) A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat Med 15: 1016–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Jove R (2004) The STATs of cancer—new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D (2007) Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J et al. (2006) Impaired regulation of NF-κB and increased susceptibility to colitis-associated tumorigenesis in CYLD-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 116: 3042–3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Kroemer G (2008) Immunological aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 59–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]