Abstract

In this longitudinal study, we investigated the mechanisms by which Chinese American parents’ experiences of discrimination influenced their adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors (i.e., cultural misfit, discrimination, attitudes toward education). We focused on whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress moderated or mediated this relationship. Participants were 444 Chinese American families. Results indicated no evidence of moderation, but we observed support for mediation. Parental experiences of discrimination were associated with more ethnic-racial socialization practices and greater parental perpetual foreigner stress. More ethnic-racial socialization was related to greater cultural misfit in adolescents, whereas more perpetual foreigner stress was related to adolescents’ poorer attitudes toward education and more reported discrimination. Relationships between mediators and outcomes were stronger for fathers than for mothers.

Keywords: adolescence, Asian Americans, culture/race/ethnicity, development/outcomes, discrimination, intergenerational transmission

Parents play a critical role in the socialization of children and adolescents. Although much of the extant research on parenting in the United States has focused on European American samples, increased attention to the parenting practices in Asian American families has documented the importance of parenting for child and adolescent development across domains (Chao & Tseng, 2002; S. Y. Kim & Wong, 2002). Whereas some research suggests that parents’ influence on their offspring declines during adolescence as youth spend increasing amounts of time with peers (see Steinberg & Morris, 2001, for review), the interdependence and collectivism of the Asian culture generally and the Chinese culture specifically suggest continually strong ties between parents and children across the life course (see Yee, DeBaryshe, Yuen, Kim, & McCubbin, 2007, for discussion). The cultural value of filial piety only reinforces this connection between parents and children, encouraging the younger generation, regardless of age, to treat their elders with reverence and respect and look to them for guidance (Cheung, Lee, & Chan, 1994; Hsu, 1953). As such, for the lives of Asian American adolescents, parents play an integral and pervasive role in their development.

The critical role of Asian American parents may be one key factor for unpackaging Asian American adolescents’ experiences of discrimination and ethnicity-related stress. Although limited, research has documented the pernicious influences of discrimination in the lives of Asian American youth (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Romero, Carvajal, Valle, & Orduna, 2007). Whereas scholars have focused some attention on the consequences of discrimination for Asian American adolescents, almost no research has examined the precursors of adolescents’ discrimination and other ethnicity-related stressors. Given the influential role of parents in the lives of Asian American adolescents, whether parents’ experiences of discrimination have repercussions for their children, and the processes by which this might occur, is an area ripe for inquiry. The current study seeks to fill this void by exploring the possible mechanisms by which Chinese American parents’ experiences of discrimination might influence their children’s perceptions of discrimination, sense of cultural misfit, and attitudes toward education. Specifically, we explore whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and their stress over the perpetual foreigner stereotype mediate this relationship or whether the strength of this relationship varies (i.e., is moderated) by different levels of parents’ ethnic-racial socialization or perpetual foreigner stress.

Background

The United States has a long history of discrimination against Asian Americans, from anti-Asian immigration and naturalization laws passed as late as 1935 to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II to discrimination in housing, education, and employment that persists even today (see Young & Takeuchi, 1998, for review). Experiences with racism and discrimination can take many forms—direct experiences encountered by individuals of color, vicarious experiences through observations of others’ maltreatment, or daily hassles with racial/ethnic undertones (i.e., microaggressions, microstressors; see Harrell, 2000, for review). The deleterious effects of discrimination are pervasive, affecting not only Asian American adults’ economic and occupational prospects, but their physical and mental health as well (Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007; Lee, 2003; Mossakowski, 2003; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008; Young & Takeuchi).

Experiences of discrimination and racism, whether experienced directly or merely observed, both contribute to stress within the target (or member of the targeted group) and engender transgenerational transmission, a mechanism by which adults adopt a variety of ethnic-racial socialization practices in their interactions with the younger generation (Harrell, 2000). Placing this into a larger context of child and adolescent development by using components from Garcia Coll and colleagues’ (1996) integrative model for minority youth, parents’ experiences with racism, prejudice, and discrimination, and the stress associated with these experiences, influence family processes, including parents’ choices around ethnic-racial socialization of their children. These practices, in turn, influence minority children’s developmental competencies, including their biculturalism and ability to cope with discriminatory encounters. These processes may be particularly relevant for Chinese American families, as Chinese American children are traditionally well integrated into their parents’ social worlds (Ho, 1989; Hsu, 1953), and Chinese culture emphasizes the importance of the collective and “getting along” with others (Chao, 1995). As such, when Chinese American parents encounter discriminatory treatment, the effects may be particularly detrimental given the cultural focus on group harmony (Kwan, Bond, & Singelis, 1997), and, because of the strong ties between parents and children in the Asian culture, the effects of parents’ discrimination experiences may reverberate in their interactions with and socialization of their children, ultimately affecting children’s outcomes.

For Asian American families, experiences of discrimination may be closely tied to challenges around minority status, specifically as a social status position (Yee et al., 2007). Theorists argue that minority status limits available opportunities in the stratified U.S. society (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; C. J. Kim, 1999), and experiences of discrimination only serve to reinforce social status positions and contribute to stress around “being different” (Yee et al.). Research has corroborated this theorized link, documenting the relationship between discrimination and stress with Asian American samples (Liang, Alvarez, Juang, & Liang, 2007; Liang, Li, & Kim, 2004). This stress may be particularly salient for Asian Americans because of their “model minority” label, which inaccurately suggests that Asian Americans are either exempt from or immune to discriminatory treatment (Wong & Halgin, 2006; Young & Takeuchi, 1998).

In addition to invoking stress in the target, discriminatory experiences can also influence how parents talk with their children about race/ethnicity. Research suggests that African American and Latino parents who experience discrimination are more likely to use ethnic-racial socialization practices, partially motivated by the fear that their children will also become targets of discrimination (Berkel et al., 2009; Hughes, 2003; Hughes & Johnson, 2001). As Fischer and Shaw (1999) argue, use of ethnic-racial socialization practices presupposes, at minimum, the socializing agent’s awareness of racism and prejudice. Use of ethnic-racial socialization practices is associated with a variety of developmental outcomes, some positive and some negative. For example, research on African American families suggests that use of ethnic-racial socialization practices supports better mental health outcomes, greater ethnic-racial identity, and more positive interracial attitudes in youth and young adults as well as buffers the negative relations between experiences of discrimination and mental health outcomes (Berkel et al.; Fischer & Shaw; Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007; Hughes et al., 2006; McHale et al., 2006; Umana-Taylor, Bhanot, & Shin, 2006). In contrast, adolescents and young adults who receive more ethnic-racial socialization messages are more likely to report experiencing discrimination across contexts (i.e., institutional, educational), as seen in research with Asian Americans and other racial/ethnic groups (Alvarez, Juang, & Liang, 2006; Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006), and they are more likely to report acculturative stress (Thompson, Anderson, & Bakeman, 2000).

Current Study

The current study seeks to elucidate the mechanisms by which Chinese American parents’ experiences of discrimination influence their adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors, including perceptions of discrimination, cultural misfit, and attitudes toward education. Our decision to focus specifically on Chinese American families was a deliberate one; there exists great diversity in the Asian American population in terms of not only migration patterns, but also academic achievement, educational attainment, occupational status, and rates of risk behaviors (Leong et al., 2006). By focusing on a single ethnicity within the larger Asian American population, we are better able to control for possible confounds associated with this diversity.

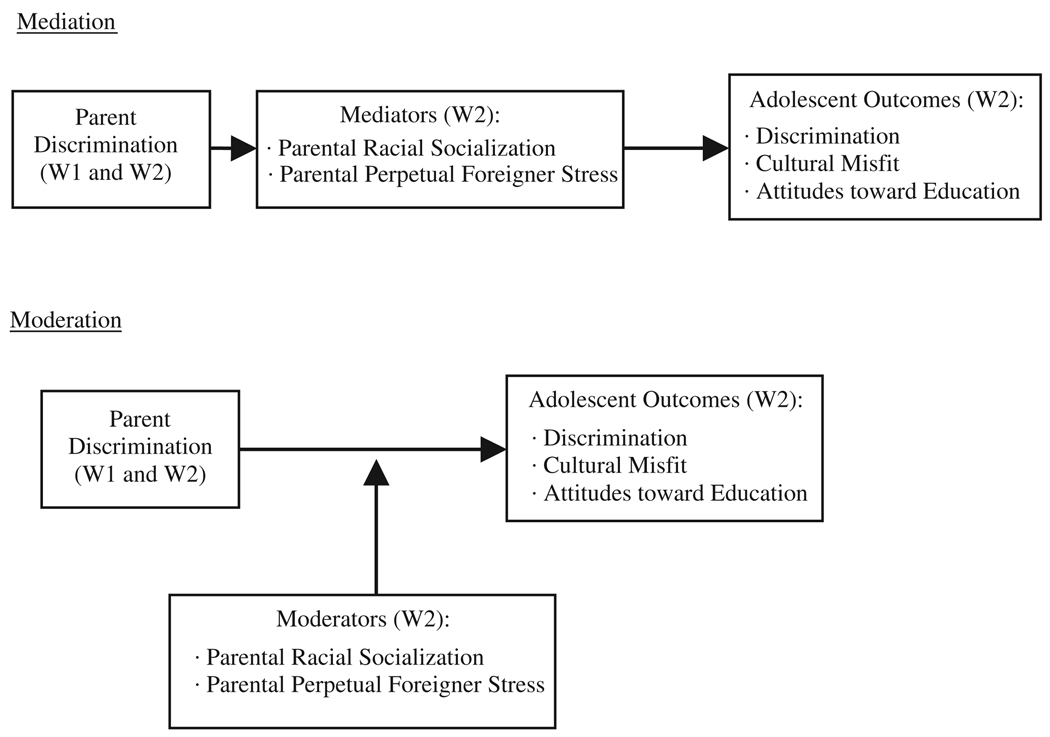

The research highlighted above indicates that adults’ experiences of discrimination are related to both ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress, and ethnic-racial socialization practices are related to adolescent and young adults’ ethnicity-related stressors. One method for examining relationships among these domains more comprehensively would be to explore whether parents’ socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress mediate the relationship between parents’ discrimination and adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors (see upper portion of Figure 1). This is consistent with Garcia Coll and colleagues’ (1996) integrative model, which suggests that parents’ experiences of discrimination exert their influence on adolescents’ developmental competencies indirectly via adaptive culture and family interactions. We focus our attention on these components of the larger integrative model because we believe these domains are most relevant to adolescents’ experiences of discrimination and other ethnicity-related stressors. If we find evidence for this mediated relationship, we expect that parents who report higher levels of discrimination will use more ethnic-racial socialization messages and report more stress over the perpetual foreigner stereotype. We hypothesize that stronger socialization messages and greater stress, in turn, will be associated with adolescents’ ethnicity-related stress in terms of more reports of discrimination, greater sense of cultural misfit, and poorer attitudes toward education.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model linking parents’ discrimination experiences to adolescents’ attitude toward education, sense of cultural misfit and discrimination through parents’ racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress.

Alternatively, the association between parents’ discrimination and adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors may be moderated by parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress (see lower panel of Figure 1). Previous research has focused particular, albeit limited, attention on the possible moderating role of socialization practices. Fischer and Shaw (1999) identified ethnic-racial socialization practices as a moderator of the relationship between experiences of discrimination and psychosocial outcomes for African American youth, finding socialization practices ameliorated some of the negative effects of perceived discrimination on mental health. An Australian study found that the association between parents’ and adolescents’ racial attitudes was stronger in families that reported low or moderate levels of general socialization practices (e.g., adaptability, empathy, support; White & Gleitzman, 2006). Given the integration of Asian American youth into their parents’ social worlds, it is possible that youth may directly observe their parents’ experiences of discrimination, which may heighten their awareness of both overt and more subtle acts of discrimination in their own lives. To the extent that ethnic-racial socialization messages and parental stress reinforce this relationship, making youth’s awareness of their race/ethnicity more salient, one might expect differences to emerge in the magnitude of the association between parents’ discrimination and adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors. If we observe evidence of moderation, we expect that the deleterious effects of parents’ discrimination on adolescent outcomes will be exacerbated when parents experience higher levels of stress and use more ethnic-racial socialization practices.

In testing the competing the mediation and moderation models, we examined relationships contemporaneously (all measures observed for parents and adolescents when adolescents are in high school) and longitudinally (parent discrimination reported when adolescents are in middle school; all other measures reported when adolescents are in high school). Initially, separate models were conducted for mothers and fathers. Although research on Asian American families is limited, some evidence suggests that Asian American mothers and fathers play distinct roles in the family system, roles governed by both traditional and evolving Chinese cultural values and norms (Shek, 2005, 2007; Wilson, 1974) that they employ different parenting strategies (see S. Y. Kim & Wong, 2002, for review), and that these strategies translate to differential effects on their offspring (Benner & Kim, in press; Chen, Liu, & Li, 2000). Moreover, recent research indicates that Asian American men report experiences of discrimination more often than Asian American women (Alvarez et al., 2006). Given this range of gender differences across domains, we also examined whether the strength of relationships among study constructs were equivalent for mothers and fathers.

Method

Participants

Participants were 444 Chinese American families participating in a short-term longitudinal study. Adolescents were initially recruited from seven middle schools in Northern California (Wave 1), with a Wave 2 follow-up occurring approximately 4 years later, when adolescents were in high school. Slightly more than half of the sample (54%) were girls (M age = 13.0 years, SD = 0.7, at Wave 1 and 17.1 years, SD = 0.8, at Wave 2). Most adolescent participants were born in the United States (75%), but most of their parents (87% of fathers and 90% of mothers) were foreign born, primarily from Hong Kong and the Guangdong province of Southern China. Most adolescents resided in two-parent homes (86%). At Wave 1, the average parent sample age was 47.9 years for fathers (SD = 6.2) and 44.0 years for mothers (SD = 4.8). The median annual family income range was $30,001 – $45,000, although the income distribution exhibited considerable variability, with 11% reporting less than $15,000 and 9% reporting more than $105,000.

Procedure

After gaining consent from local school districts, middle schools with a substantive population of Asian American students (at least 20% of the student body) were selected for participation, resulting in seven eligible middle schools. Chinese American families were then identified by school administrators. Of those families contacted, 47% consented to participate in the study. Four years later, families were approached to participate in the second data collection wave. Approximately 80% of Wave 1 participating families completed questionnaires at Wave 2. At each wave, the entire family received nominal compensation ($30 at Wave 1 and $50 at Wave 2) for their participation.

Both English and Chinese version questionnaires were available to participants. To ensure comparability of the two versions, questionnaires were translated into Chinese and then back-translated into English. Inconsistencies were resolved by two bilingual research assistants, with careful consideration of items’ culturally appropriate meaning. The majority of adolescents used the English version questionnaires (85%); more than 70% of fathers and mothers completed the Chinese version.

Attrition analyses examining families who participated in both data collection waves and those who attrited at Wave 2 revealed no significant differences between groups on key demographic variables (i.e., parental education, family income, parent and child nativity status, child or parent age, parent marital status) with one exception—boys were more likely to have attrited than girls, χ2(1) = 16.1, p < .001; in response to this difference, adolescent gender is included as a covariate for all analyses.

Measures

All measures, drawn from surveys of adolescents and their parents, were assessed when adolescents were in middle school (7th or 8th grade) or in high school (11th or 12th grade), and some were assessed in both middle and high school. Cronbach’s alphas for all measures for both the Chinese and English versions of the survey appear in the appendix.

APPENDIX.

Cronbach’s alphas for all measures by survey language

| Chinese Version |

English Version |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| Discrimination | ||||

| Mothers | .83 | .86 | .90 | .86 |

| Fathers | .85 | .84 | .92 | .92 |

| Ethnic/racial socialization practices | ||||

| Mothers | — | .81 | — | .79 |

| Fathers | — | .77 | — | .83 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress | ||||

| Mothers | — | .87 | — | .92 |

| Fathers | — | .89 | — | .88 |

| Outcomes (adolescent-report) | ||||

| Discrimination | — | .89 | — | .86 |

| Misfit with | — | .78 | — | .81 |

| American | ||||

| culture | ||||

| Attitudes toward | — | .65 | — | .79 |

| education | ||||

Note: —indicates measure was not collected at the given wave.

Discrimination

We measured parents’ general perceptions of discrimination using Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams’s (1999) measure of chronic daily discrimination. Participants were asked, “On a day-to-day basis, how often do you experience each of the following types of discrimination?” A sample item is “I am treated with less respect than other people.” Our measure included one additional item not included in the original measure (“People assumed my English is poor.”) to make the scale more relevant to Asian Americans, who report assumptions of nonnative English skills as a common misrepresentation by others (Cheryan & Monin, 2005). Ratings ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (often), with higher mean scores indicating greater experiences of daily discrimination (Cronbach’s α = .85 for mothers at both Wave 1 and Wave 2 and .87 for fathers at both Wave 1 and Wave 2).

Ethnic-racial socialization practices

We adapted items from Hughes and Johnson’s (2001) measure of ethnic-racial socialization behaviors. Our scale included four items that queried parents’ socialization practices around preparing their children for racial bias (“talk to my child about the possibility that some people might treat him/her badly or unfairly because s/he is Chinese”). Items were rated on a 3-point scale from 1 (seldom) to 3 (often), with higher mean scores indicating greater ethnic-racial socialization by parents (Cronbach’s α = .80 and 0.79 for mothers and fathers, respectively).

Stress over the perpetual foreigner stereotype

Five items were used to measure parents’ stress over being stereotyped as foreigners. All items were preceded with the phrase “on a day-today basis …” The research team developed this measure on the basis of previous work of a number of researchers. Specifically, one item (“People assume I am from another country.”) was originally developed by Cheryan and Monin (2005). Two items (“People criticize me for not speaking/writing English well.” and “People criticize me for speaking Chinese.”) were adapted from the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory developed by Rodriguez and colleagues (Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, and Garcia-Hermandez, 2002). We also drew one item (“I feel misunderstood or limited in daily situations because of my English skills.”) from Benet-Martinez and Haritatos (2005) and one (“People assume I am a FOB (fresh-off-the-boat).”) from research conducted by Pyke and Dang (2003). For each item, parents were asked how stressful each of the above experiences was, with responses ranging from 1 (not stressful) to 4 (very stressful). Higher mean scores reflect more stress over being stereotyped as foreigners (Cronbach’s α = .90 for both mothers and fathers). Because of possible overlap between the foreigner stereotype stress measure and our one newly incorporated discrimination item, we examined the correlation between the foreigner stress measure and the discrimination measure with and without the “assume my English is poor” item. Results indicate that correlations were similar in size (ranging from a .01- to .05-point difference) across waves and across mothers and fathers, and significance levels did not change.

Adolescent outcomes

We included three ethnicity-related stressors at Wave 2. First, adolescents completed a discrimination measure identical to that of the parents (Cronbach’s α = .86). Adolescents also reported on feelings of misfit with American culture using items from the four-item misfit scale of the Cultural Estrangement Inventory (Cozzarelli & Karafa, 1998). Some items from the original scale were modified slightly to focus on Americans (rather than having no reference point), and all items in the current study were rated on a 5- rather than 7-point scale. A sample item is “I feel that I somehow don’t fit in with Americans.” Ratings ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher mean ratings indicating greater cultural misfit (Cronbach’s α = .85). Finally, we assessed adolescents’ attitudes toward education using four items from Mickelson’s (1990) concrete attitudes toward education scale. As Mickelson argues, concrete attitudes about education take into account the perceived equity in return on educational investments by important adults in children’s lives and thus better capture the lived realities of potential unfair return for educational investment in diverse (particularly minority) populations. A sample item is “Studying in school rarely pays off later with good jobs.” Ratings ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items were reverse coded, with higher mean scores reflecting more positive concrete attitudes toward education (Cronbach’s α = .67).

Covariates

For all analyses, we used two adolescent-reported covariates, gender and nativity status, and two parent-reported covariates, household income and highest education achieved. We also included a covariate to capture region, as our sample was drawn from two distinct areas in northern California. For the mediation analyses, we conducted multiple group analyses to determine if the strength of relationships differed for girls and boys or for those born in the United States versus those born abroad. Although limited, some research suggests differential family processes for Asian American girls and boys (Suarez-Orozco & Qin, 2006) and within native- versus foreign-born households (Hernandez, 2004); moreover, Chinese American males and foreign-born Chinese youth may be at heightened risk for discriminatory treatment (Qin, Way, & Mukherjee, 2008; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). In general, the relationships did not differ across groups (i.e., no evidence of moderation). As such, we retained adolescent gender and nativity status, along with family income and parent education, solely as covariates in the analyses.

Analytic Strategy

The crux of our study examined whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress over being treated as perpetual foreigners moderated or mediated the relationship between parents’ discrimination and adolescents’ discrimination, sense of cultural misfit, and concrete attitudes toward education (see Figure 1 for the conceptual model). The current data set included some missing data, and traditional methods for dealing with missing data (e.g., pairwise or listwise deletion) can result in biased estimates and an increase in Type II error rates (Acock, 2005). One mechanism to address issues of missingness is multiple imputation, which creates m multiply imputed data sets in which any missing values in the original data set are replaced with plausible values (Rubin, 1987). We used PROC MI in SAS for the multiple imputation, creating 30 imputed data sets, as recommended by Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath (2007). We then conducted all statistical analyses on the 30 imputed data sets and used pooled parameter estimates and standard errors across the imputed data sets to make valid univariate inferences.

For the moderation analyses, we conducted a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions using PROC REG in combination with MIANALYZE in SAS (in order to obtain pooled results across the imputed data sets). We introduced main effects and linear interaction terms (see Baron & Kenny, 1986) to test whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices or stress over being treated as perpetual foreigners moderated the relationship between Wave 1 or Wave 2 parent discrimination and each adolescent outcome. Separate analyses were conducted for each moderator and each outcome as well as for mothers and fathers. Because of the large number of regressions conducted, we used a Bonferroni adjustment to identify a family-wise error rate (p < .004; Shaffer, 1995).

To test whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress mediated the relationship between parent discrimination and adolescent outcomes, we conducted two path analysis models per parent using a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework in Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 2006). The longitudinal model included Wave 1 parent discrimination as the exogenous variable, and the contemporaneous model included Wave 2 parent discrimination as the exogenous variable. In both models, mediators and adolescent outcomes were measured at Wave 2. We used the TYPE = IMPUTATION in Mplus to test the path models across the 30 imputed data sets. In relation to tests of mediation, Baron and Kenny (1986) proposed a causal steps approach that required a significant relationship between (a) the independent variable and the mediator, (b) the independent variable and the dependent variable, and (c) the mediator and the dependent variable. Recent critiques of this causal steps approach for testing mediation suggest the method may be both too restrictive and underpowered (see Dearing & Hamilton, 2006, for a review), particularly for longitudinal models in which substantial time has elapsed between measurement of the independent and dependent variables (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), which is the case for the current study (4 years separated the measurement of the predictor and the distal outcomes). As such, inferences for indirect effects were based on Sobel’s (1982) asymptotic z test; use of the Sobel test is generally recommended for studies with larger sample sizes (see Bollen & Stine, 1990; Dearing & Hamilton; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Our final set of analyses examined the strength of modeled relationships across the estimated models for mothers and fathers. We used a strategy similar to that employed in the testing of moderation using a multiple-group analysis; instead of using parent as the grouping variable, however, we modeled mother and father data within the same covariance matrix to account for the within-family dependence. We used a stepwise process whereby we initially estimated a base (i.e., configural) model that included relationships for both mother- and father-report data, with all model parameters freely estimated; we then included a series of increasingly restrictive constraints on the model parameters and observed whether or not doing so led to a significant decrease in the overall model fit (Millsap & Kwok, 2004; Reise, Widaman, & Pugh, 1993). Omnibus tests (e.g., chi-square difference tests and comparisons of comparative fit index [CFI] values) were relied upon to determine whether introduction of parameter constraints resulted in a significant decrease in the model fit. Significant decreases would suggest that the more restrictive model does not fit the data as well as the less restrictive model and, as such, that there are meaningful differences across mothers and fathers. If invariance was not tenable for an invariance path under consideration (i.e., if we observed a significant decrease in model fit), we allowed for partial invariance by modeling those parameters to be freely estimated in the model (Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthen, 1989). In this manner, invariance analyses allow one to test whether and where precisely the differences lie in a complex, multimediated model.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for each measure as well as correlations among variables. Although mean reports of discrimination were relatively low for parents and adolescents, more than 95% of mothers and fathers reported at least some experience with discrimination at both waves, and 92% of adolescents reported at least some discrimination at Wave 2. Moreover, the number of discriminatory experiences that participants reported (at least rarely) was also high. At Wave 1, of the 10 possible discriminatory experiences, mothers reported experiencing an average of almost 7 (M = 6.75, SD = 2.75), and fathers reported slightly more than 7 (M = 7.17, SD = 2.75). Paired-samples t tests revealed no differences in perceptions of discrimination across mothers and fathers, t(443) = 0.95, ns at Wave 1 and 1.56 at Wave 2). Adolescent reports of discriminatory actions averaged more than 5 (M = 5.65, SD = 3.19). For mothers and fathers, the most common types of discrimination experienced were being treated with less courtesy, being treated with less respect, and people assuming their English was poor (reported as occurring at least rarely by 79% to 90% of parents at each wave). Every item in the scale was endorsed as occurring at least rarely by 40% of fathers and 30% of mothers at each wave. Adolescents, in contrast, were most likely to report “people act as if they are better than I am” (78% reported this occurring at least rarely). Although less common, adolescents also frequently reported being treated with less courtesy (73%) and being treated with less respect (69%).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Discrimination W1 (M) | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | Discrimination W1 (F) | .30*** | — | |||||||||

| 3 | Discrimination W2 (M) | .38*** | .14* | — | ||||||||

| 4 | Discrimination W2 (F) | .22*** | .40*** | .47*** | — | |||||||

| 5 | Racial socialization W2 (M) | .13* | .13* | .26*** | .17** | — | ||||||

| 6 | Racial socialization W2 (F) | .02 | .18** | .12* | .23*** | .49*** | — | |||||

| 7 | Perpetual foreigner stress W2 (M) | .08 | −.00 | .25*** | .19** | .25*** | .11 | — | ||||

| 8 | Perpetual foreigner stress W2 (F) | −.07 | .16* | .14* | .35*** | .18** | .16* | .43*** | — | |||

| 9 | Discrimination W2 (A) | .08 | .01 | .16** | .15** | .09 | .15** | .12* | .23*** | — | ||

| 10 | Cultural misfit W2 (A) | .10 | .06 | .14** | .11* | .12* | .21*** | .08 | .10 | .37*** | — | |

| 11 | Attitudes toward education | −.11* | −.14* | −.12* | −.15** | −.17** | −.16** | −.23*** | −.28*** | −.31*** | −.37*** | — |

| W2 (A) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.96 | 2.02 | 1.86 | 1.95 | 1.56 | 1.59 | 2.00 | 1.91 | 1.77 | 2.30 | 3.48 | |

| SD | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

Note: W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2, M = mother, F = father, A = adolescent. N = 444

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Like discrimination, mean reports of ethnic-racial socialization practices were relatively low in our sample; an examination of the individual socialization practices, however, indicated that the Chinese American parents in the sample commonly (i.e., sometimes or often) talked to their children about what to do if someone insulted or harassed them (76% of mothers and 72% of fathers) and talked to their children about how being Chinese meant they had to do better in school than other people in order to get the same kind of success in the future (51% of mothers and 56% of fathers). The paired-sample t test revealed no differences between mother and father reports of socialization practices, t (443) = 1.47, ns. Parents also experienced stress over being stereotyped as foreigners. Most commonly this stress centered on their English language skills. In total, 67% of mothers and 70% of fathers reported feeling at least some stress that people assumed their English was poor, and 63% of mothers and 62% of fathers indicated at least some stress over feeling misunderstood or limited in daily situations because of their English skills. The paired-sample t test indicated that fathers reported significantly more stress around being stereotyped as foreigners than mothers, t (443) = 5.57, p < .001.

Tests of Moderation

Our first set of analyses examined whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress over being stereotyped as foreigners moderated the relationship between parents’ experiences of discrimination and adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit, discriminatory experiences, and attitudes toward education. We observed no evidence that either mothers’ or fathers’ ethnic-racial socialization or perpetual foreigner stress moderated any of the relationships under study. To verify that our null moderation findings were not an artifact of low power, we conducted a post hoc analysis to determine achieved power in the analysis using G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). The analysis calculates an f-square effect size index (see Cohen, 1988). In the analysis, we specified alpha levels of both .05 and .004, to reflect the traditionally accepted alpha level as well as our calculated family-wise error rate. Results indicate that our power to detect a small effect size (f2 = .04) was .99 at alpha of .05 and .91 at alpha of .004, indicating strong power to detect a small effect.

Tests of Mediation

Contemporaneous relationships

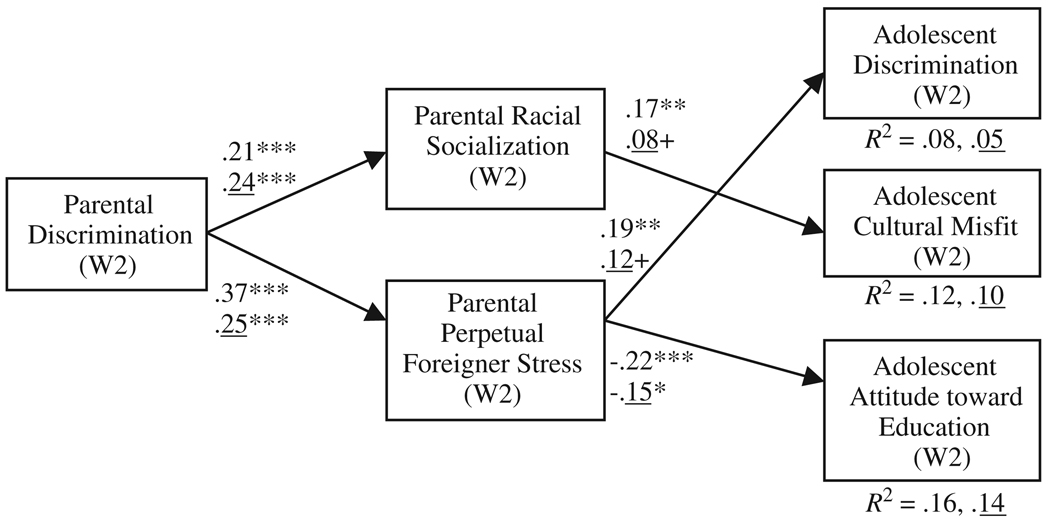

Our first model examined the contemporaneous relationships among study constructs at Wave 2. Specifically, we examined whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress mediated the relationship between parents’ experiences of discrimination and adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors. As shown in the top coefficients in Figure 2, for fathers, greater experiences of discrimination were associated with greater engagement in ethnic-racial socialization practices and more stress over being stereotyped as foreigners. Fathers’ increased ethnic-racial socialization practices, in turn, were linked to a greater sense of cultural misfit for adolescents. More paternal stress over being stereotyped as foreigners was related to higher reports of discrimination by adolescents and poorer attitudes toward education. Sobel asymptotic z tests of the indirect effects (Sobel, 1982) indicate that ethnic-racial socialization practices mediated the relationship between fathers’ experiences of discrimination and adolescents’ cultural misfit (z = 2.31, p < .05). In contrast, fathers’ stress over being stereotyped as foreigners mediated the relationship between their experiences of discrimination and both adolescents’ experiences of discrimination (z = 2.73, p < .01) and their attitudes toward education (z = −2.91, p < .01).

FIGURE 2.

Model examining contemporaneous relationships between wave 2 parent-reported discrimination, racial socialization practices, and stress over being stereotyped as a foreigner and adolescent-reported discrimination, sense of cultural misfit, and positive attitudes toward education.

Note: Separate models for fathers and mothers were estimated, with mother coefficients underlined. Father model: CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .025, SRMR = .011. Mother model: CFI = .99, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = .013. Only significant paths are shown. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, +p < .10. Each model includes the following covariates: adolescent gender, adolescent nativity status, parent-reported household income, and parent education.

Direct effects from the path analysis model for mothers were identical to those of fathers (underlined coefficients in Figure 2), with two exceptions—the relationship between mothers’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit was only marginally significant, as was the relationship between mothers’ stress over being stereotyped as foreigners and adolescents’ experiences of discrimination. Analyses of indirect effects revealed that, like results for fathers, mothers’ stress over being stereotyped as foreigners mediated the relationship between mothers’ experiences of discrimination and adolescents’ attitudes toward education (z = −2.13, p < .05). Consistent with the marginal findings for direct effects to our other adolescent outcomes, we observed only trend-level support for maternal reports of perpetual foreigner stress mediating the relationship between mothers’ experiences of discrimination and the discriminatory experiences of their adolescents (z = 1.61, p = .11) as well as ethnic-racial socialization practices mediating the relationship between mothers’ experiences of discrimination and adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit (z = 1.65, p = .10).

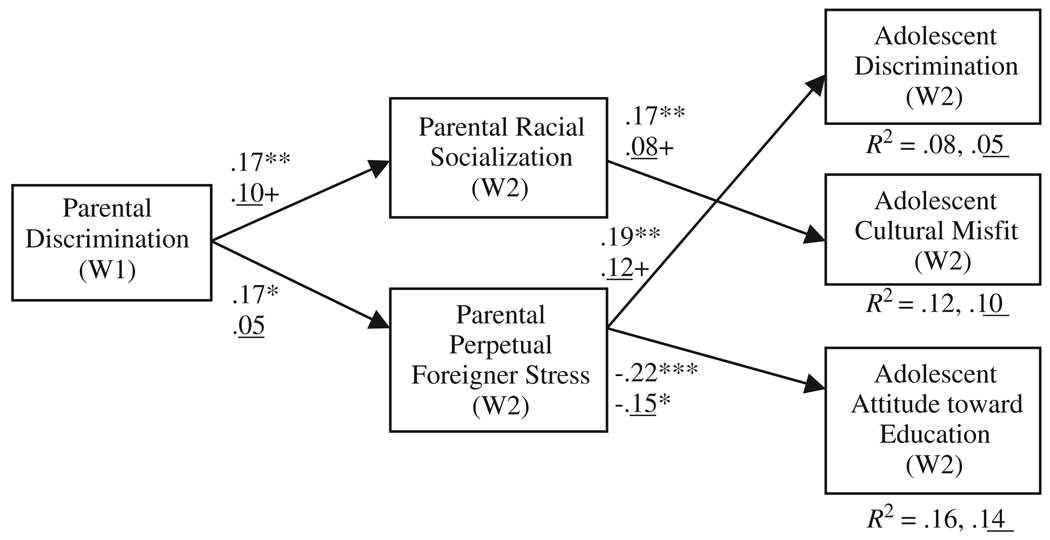

Longitudinal relationships

We next examined whether parents’ experiences of discrimination at Wave 1 (when their children were in middle school) exerted influence on later ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress over being stereotyped as foreigners, both measured at Wave 2 (when their children were in high school). As shown in the top coefficients in Figure 3, fathers’ experiences of discrimination when their children were in middle school influenced later ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress over being stereotyped as foreigners, although coefficients were noticeably smaller than those for the contemporaneous influences. In contrast, mothers’ experiences of discrimination when their children were in middle school were only marginally related to later socialization practices and were unrelated to later stress over being stereotyped as foreigners. Indirect effects for the model for fathers were consistent with those from the contemporaneous model, with paternal ethnic-racial socialization practices mediating the relationship between paternal discrimination and adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit (z = 2.00, p < .05) and paternal perpetual foreigner stress mediating the relationship between paternal discrimination and both adolescent discrimination (z = 1.80, p = .07) and adolescent attitudes toward education (z = −1.85, p = .07). Results for the mother-focused model showed no statistical evidence for indirect effects for the longitudinal model.

FIGURE 3.

Model examining longitudinal relationships between wave 1 parent-reported discrimination, wave 2 parent racial socialization practices, and stress over being stereotyped as a foreigner and wave 2 adolescent-reported discrimination, sense of cultural misfit, and positive attitudes toward education.

Note: Separate models for fathers and mothers were estimated, with mother coefficients underlined. N = 444. Father model: CFI = .98, RMSEA = .063, SRMR = .014. Mother model: CFI = .98, RMSEA = .061, SRMR = .018. Only significant paths are shown. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, +p < .10. Each model includes the following covariates: adolescent gender, adolescent nativity status, parent-reported household income, and parent education.

Invariance across mothers and fathers

The final set of analyses explored whether the relationships under study differed across mothers and fathers. As shown in Table 2, we observed no differences in the relationships between parent discrimination and either ethnic-racial socialization practices or perpetual foreigner stress across mothers and fathers. We did, however, observe differences across parents in the relationships between the mediators and outcomes. Specifically, in both the contemporaneous and longitudinal models, the relationships between parental ethnic-racial socialization and adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit as well as the relationships between parental perpetual foreigner stress and both adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination and attitudes toward education were stronger for fathers than mothers.

Table 2.

Model Invariance Tests Across Mothers and Fathers for the Contemporaneous and Longitudinal Models

| χ2(df) | Δχ2(Δ df) | p Value | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contemporaneous model | ||||||

| Base (configural) model | 33.5 (14) | — | — | .977 | .055 | .024 |

| Predictors to mediators | 37.3 (16) | 3.8 (2) | .150 | .975 | .054 | .025 |

| Racial socialization to discrimination, cultural misfit | 40.7 (18) | 3.4 (2) | .183 | .973 | .053 | .026 |

| Racial socialization to attitude toward education | 45.8 (19) | 5.1 (1) | .024 | .968 | .056 | .026 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to discrimination | 45.1 (19) | 4.4 (1) | .036 | .969 | .055 | .027 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to cultural misfit | 42.3 (19) | 1.6 (1) | .206 | .973 | .052 | .026 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to attitude toward education | 47.3 (20) | 5.0 (1) | .025 | .968 | .055 | .026 |

| Longitudinal model | ||||||

| Base (configural) model | 60.8 (14) | — | — | .934 | .086 | .033 |

| Predictors to mediators | 62.5 (16) | 1.7 (2) | .427 | .934 | .080 | .033 |

| Racial socialization to discrimination, cultural misfit | 65.8 (18) | 3.3 (2) | .192 | .933 | .077 | .034 |

| Racial socialization to attitude toward education | 70.9 (19) | 5.1 (1) | .024 | .927 | .078 | .034 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to discrimination | 70.2 (19) | 4.4 (1) | .036 | .928 | .077 | .034 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to cultural misfit | 67.4 (19) | 1.6 (1) | .206 | .932 | .075 | .034 |

| Perpetual foreigner stress to attitude toward education | 72.4 (20) | 5.0 (1) | .025 | .927 | .076 | .034 |

Note: Contemporaneous models include all measures at Wave 2 (when adolescents were in high school). Longitudinal model includes parent discrimination at Wave 1 (middle school) and mediators and outcomes at Wave 2. CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, SRMR = standardized root mean residual. Bold paths denote significant difference in model fit.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we investigated the mechanisms by which Chinese American parents’ experiences of discrimination influenced their adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors. We focused particular attention on whether parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and stress over being stereotyped as perpetual foreigners either moderated or mediated this relationship. Overall, results indicated no evidence that either socialization practices or perpetual foreigner stress moderated the relationships under study. In contrast, we observed support for the mediational model with both cross-sectional and longitudinal data for fathers and cross-sectional data for mothers. Results indicated that parental experiences of discrimination were associated with more ethnic-racial socialization practices and greater perpetual foreigner stress, although results were weaker for the longitudinal models, particularly for mother reports. In turn, more ethnic-racial socialization practices were related to a stronger sense of cultural misfit in adolescents, whereas more perpetual foreigner stress was related to more adolescent reports of discrimination and poorer attitudes toward education.

We suspect support for the mediation but not moderation models may reflect the transactional nature of the intergenerational experiences of discrimination. Our findings are consistent with the tenets of Garcia Coll and colleagues’ (1996) integrative model, which proposes parents’ experiences of discrimination wield their influence on youth’s developmental outcomes indirectly via adaptive culture and family interactions. Although Chinese American adolescents such as those in our sample may be more integrated into their parents’ social worlds, these adolescents are less likely to witness acts of discrimination in certain ecologies in which their parents are embedded, such as in their places of employment. Moreover, research suggests that Asian American parents rarely discuss experiences of discrimination with their children, perhaps reflecting cultural values of emotional restraint and group harmony (Hughes et al., 2006). As such, parent-child transactions around racial/ethnic issues, either through ethnic-racial socialization practices or manifestations of parents’ stress around the perpetual foreigner stereotype, may be the driving force that transmits parents’ experiences of discrimination to their children. In turn, these socialization messages and parental stress seemingly influence Chinese American adolescents’ perceptions of their own discrimination and feelings of cultural misfit while diminishing beliefs regarding the payoff of education. The integrative model suggests that these relationships may be recursive in nature, such that adolescents’ reactions to their environments influence their subsequent development. In the current study, we were able to test the relationships between both socialization practices and stress and adolescent outcomes at a single moment in development (middle adolescence). As such, future research should explore whether the relationship between both parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress and adolescent outcomes strengthens over time.

In addition to support for the mediation model, invariance testing showed that the relationships between both ethnic-racial socialization practices and parental perpetual foreigner stress and adolescents’ ethnicity-related outcomes were stronger for fathers than mothers. The differences in strength of effects may have their root in Chinese cultural values and the immigrant experience. Chinese society is heavily influenced by Confucian beliefs, which emphasize strong patriarchal values (Chao & Tseng, 2002). As such, experiences of discrimination and the loss of status associated with discrimination may be particularly challenging for Chinese immigrant men, as they enjoyed higher status within their native culture (at least relative to their wives). This finds some support in our study, as fathers expressed greater stress over being stereotyped as perpetual foreigners in comparison to mothers. In the patriarchal Chinese culture, fathers also exercise greater authority within the family unit, and they take primary responsibility for instilling cultural values and proper social behavior in their children, whereas mothers take on a more emotionally supportive role (Chao & Tseng; Chen et al., 2000; Ho, 1989). Chen and colleagues argue that this may, in part, result in a stronger paternal influence on children and adolescents’ “social status, leadership, and academic achievement” (p. 404). To the extent that the ethnicity-related stressors under study here are evidence of social status (or lack thereof), the stronger paternal (rather than maternal) influence is in line with expectations. It may also be that mothers’ influence occurs indirectly via mechanisms not currently under study. For example, Murry and colleagues (2008) and Brody and colleagues (2008) argue that discrimination and other stressful life events influence parenting (including warmth and nurturance) through their effects on mothers’ psychological functioning. This, coupled with Chinese American mothers’ cultural role as the emotional support for children and adolescents, suggests that parenting practices, and warmth in particular, may indeed be an important mediator through which mothers’ experiences of discrimination may influence adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors, warranting further studies with Asian American families.

Another aspect of our findings that deserves further comment is the differential effects from maternal and paternal ethnic-racial socialization practices and perpetual foreigner stress to adolescent outcomes. Chinese American parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices exerted their influence on adolescents’ sense of cultural misfit, but not their attitudes toward education or perceptions of discrimination. Brega and Coleman (1999) found that as the number of racial socialization messages increased, African American adolescents’ self-perceived stigmatization also increased. As such, it may be that greater ethnic-racial socialization practices are making adolescents in the current sample feel more stigmatized and less like they belong in U.S. culture. It is important to note that the socialization practices under study here fit most closely with Hughes and colleagues’ (2006) categorization of preparation for bias. Whether socialization messages that instead focus on cultural socialization, which promotes the positive aspects of one’s culture, would serve a protective or promotive function for Chinese American adolescents is an area for future inquiry.

Parents’ stress over the perpetual foreigner stereotype, in contrast, exerted its influence on adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination and attitudes toward education. Research suggests that Chinese American parents place strong emphasis on their children’s academic performance, envisioning education as a means to both achieve higher social status and overcome potential discrimination (Sue & Okazaki, 1990). As parents’ perceptions of discrimination increase and they feel greater stress over being stereotyped as perpetual foreigners, their messages around academics may increasingly underscore the challenges around education and the need for their children to excel to achieve social mobility and bring honor to the family. The current study’s findings corroborated this assertion, with Chinese American fathers in particular exerting a stronger influence in this regard.

Although the current study provides critical insights into the intergenerational transmission of discrimination and the role that parents’ ethnic-racial socialization and perpetual foreigner stress play, some limitations and caveats must be acknowledged. First, for the meditational models, our longitudinal findings were generally weaker than cross-sectional results, particularly for the mother-report model. It is important to note, however, that 4 years had elapsed between data collection time points, and, as such, the weaker findings are not surprising. Second, we used an abbreviated ethnic-racial socialization measure focused on parents’ preparation for bias. We observed the negative effects of these practices for our Asian American sample, but it is unknown whether a multidimensional measure that included other types of ethnic-racial socialization messages (particularly positive messages such as cultural socialization messages that instill ethnic pride) might have differential effects on adolescents’ outcomes. Relatedly, data from the current study do not distinguish between proactive and reactive ethnic-racial socialization messages. Given the age of the adolescents in our sample (11th and 12th grades) and the fact that they are reporting experiences of discrimination, it is likely that parents’ messages may be reactive in nature, offered in response to their adolescents’ experiences with discriminatory treatment. Although the current study did not measure racial socialization practices in early adolescence to adequately test proactive and reactive forms, future research, perhaps with younger Asian American samples, should examine whether proactive socialization messages have a more positive effect on youth’s ethnicity-related stressors.

The current study focused on how parents’ experiences with discrimination influenced their children’s outcomes. Research suggests, however, that these relationships may be bidirectional in nature. For example, studies have found that ethnic-racial socialization messages are more common when children have experienced discrimination (Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Lalonde, Jones, & Stroink, 2008). As such, it may be that parents’ choices and frequency of ethnic-racial socialization messages and their stress over the perpetual foreigner may be fueled, in part, by their perceptions of their children’s mistreatment. Future studies should more comprehensively explore the transactional nature of the intergenerational transmission of discrimination and other ethnicity-related stressors in Asian American families. The current study does, however, suggest that involving Asian American parents may be a critical facet of intervention and prevention work targeting Asian American adolescents’ discriminatory experiences and coping strategies. In particular, helping parents develop more effective ethnic-racial socialization strategies and better ways to cope with their own foreigner stress may help adolescents better adapt to their own discrimination experiences, sense of cultural misfit, and negative attitudes toward education.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by a Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD R24HD042849 grant awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

REFERENCES

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez AN, Juang L, Liang CTH. Asian Americans and racism: When bad things happen to “model minorities”. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:477–492. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, Haritatos J. Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Understanding Chinese American adolescents’ developmental outcomes: Insights from the family stress model. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00629.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Murry VM, Hurt TR, Chen Y-F, Brody GH, Simons RL, Cutrona C, Gibbons FX. It takes a village: Protecting rural African American youth in the context of racism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Stine R. Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methods. 1990;20:115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Brega AG, Coleman LM. Effects of religiosity and racial socialization on subjective stigmatization in African – American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22:223–242. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthen B. Testing for equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105:456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. Chinese and European American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers’ childrearing beliefs. Ethos. 1995;23:328–354. [Google Scholar]

- Chao R, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4. Social conditions and applied parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Li D. Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:401–419. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, Monin BT. “Where are you really from?”: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C, Lee J, Chan C. Explicating filial piety in relation to family cohesion. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1994;9:565–580. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzarelli C, Karafa JA. Cultural estrangement and terror management theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Hamilton LC. Contemporary advances and classic advice for analyzing mediating and moderating variables. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71(3):88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll CG, Maberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vázquez García H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Takeuchi DT. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1275–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. Future of Children. 2004;14:17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Continuity and variation in Chinese patterns of socialization. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu FLK. Americans and Chinese. Honolulu, HI: University Press of Hawaii; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:981–995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith PE, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic–racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CJ. The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society. 1999;27:105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wong VY. Assessing Asian and Asian American parenting: A review of the literature. In: Kurasaki K, Okazaki S, Sue S, editors. Asian American mental health: Assessment theories and methods. New York: Kluwer; 2002. pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan VSY, Bond MH, Singelis TM. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1038–1051. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde RN, Jones JM, Stroink ML. Racial identity, racial attitudes, and race socialization among Black Canadian parents. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2008;3:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Do ethnic identity and other-group orientation protect against discrimination for Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL, Inman AG, Ebreo A, Yang LH, Kinoshita LM, Fu M, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liang CTH, Alvarez AN, Juang LP, Liang MX. The role of coping in the relationship between perceived racism and racism-related stress for Asian Americans: Gender differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liang CTH, Li LC, Kim BSK. The Asian American Racism-Related Stress Inventory: Development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim J-Y, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, Swan-son DP. Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77:1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson RA. The attitude-achievement paradox among black adolescents. Sociology of Education. 1990;63:44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE, Kwok OM. Evaluating the impact of partial factorial invariance on selection in two populations. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:93–115. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Harrell AW, Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Simons RL, Black AR, Cutrona CE, Gibbons FX. Long-term effects of stressors on relationship well-being and parenting among rural African American women. Family Relations. 2008;57:117–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Philip CL, Cogburn CD, Sellers RM. African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke K, Dang T. “FOB” and “white-washed”: Identity and internalized racism among second generation Asian Americans. Qulaitative Sociology. 2003;26:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Qin DB, Way N, Mukherjee P. The other side of the model minority story: The familial and peer challenges faced by Chinese American adolescents. Youth and Society. 2008;39:480–506. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:552–566. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, Garcia-Hermandez L. Development of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Carvajal SC, Valle F, Orduna M. Adolescents’ bicultural stress and its impact on mental well-bring among Latinos, Asian Americans, and European Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:519–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom SR, Way N. Experiences of discrimination among African American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth and Society. 2004;35:420–451. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer JP. Multiple hypothesis testing. Annual Review of Psychology. 1995;46:561–584. [Google Scholar]

- Shek DT. Perceived parental control and parent – child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Sex Roles. 2005;53:635–646. [Google Scholar]

- Shek DT. Perceived parental control based on indigenous Chinese parental control concepts in adolescents in Hong Kong. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2007;35:123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;74:422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methods. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Qin DB. Gendered perspectives in psychology: Immigrant origin youth. International Migration Review. 2006;40:165–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Okazki S. Asian-American educational achievements: A phenomenon in search of an explanation. American Psychologist. 1990;45:913–920. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CP, Anderson LP, Bakeman RA. Effects of racial socialization and racial identity on acculturative stress in African American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6:196–210. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Bhanot R, Shin N. Ethnic identity formation during adolescence: The critical role of families. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:390–414. [Google Scholar]

- White FA, Gleitzman M. An examination of family socialisation processes as moderators of racial prejudice transmission between adolescents and their parents. Journal of Family Studies. 2006;12:247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RW. The moral state: A study of the political socialization of Chinese and American children. New York: Free Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wong F, Halgin R. The “model minority”: Bane or blessing for Asian Americans? Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2006;34:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yee BWK, DeBaryshe BD, Yuen S, Kim SY, McCubbins HI. Asian American and Pacific Islander families: Resiliency and life-span socialization in a cultural context. In: Leong FTL, Inman AG, Ebreo A, Yang LH, Fu M, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, Takeuchi DT. Racism. In: Lee LC, Zane NWS, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 401–432. [Google Scholar]