Abstract

PURPOSE:

To examine the role of health care professionals in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (MPTF) for the treatment of chronic pain across Canada.

METHODS:

MPTF were defined as clinics that advertised specialized multidisciplinary services for the diagnosis and management of chronic pain, and had staff from a minimum of three different health care disciplines (including at least one medical specialty) available and integrated within the facility. Administrative leaders at eligible MPTF were asked to complete a detailed questionnaire on their infrastructure as well as clinical, research, teaching and administrative activities.

RESULTS:

A total of 102 MPTF returned the questionnaires. General practitioners, anesthesiologists and physiatrists were the most common types of physicians integrated in the MPTF (56%, 51% and 32%, respectively). Physiotherapists, psychologists and nurses were the most common nonphysician professionals working within these MPTF (75%, 68% and 57%, respectively), but 33% to 56% of them were part-time staff. Only 77% of the MPTF held regular interdisciplinary meetings to discuss patient management, and 32% were staffed with either a psychologist or psychiatrist. The three most frequent services provided by physiotherapists were patient assessment, individual physiotherapy or exercise, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. The three most common services provided by psychologists were individual counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic therapy. The major roles of nurses were patient assessment, assisting in interventional procedures and patient education.

CONCLUSION:

Different health care professionals play a variety of important roles in MPTF in Canada. However, few of them are involved on a full-time basis and the extent to which pain is assessed and treated in a truly multidisciplinary manner is questionable.

Keywords: Health care professional, Multidisciplinary pain centre, Nursing, Physicians, Psychologist, Physiotherapist

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Examiner le rôle des professionnels de la santé dans les unités multidisciplinaires de traitement de la douleur (UMTD) pour le traitement de la douleur chronique au Canada.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les auteurs ont défini les UMTD comme des cliniques qui publicisaient des services multidisciplinaires spécialisés pour le diagnostic et la prise en charge de la douleur chronique, disposaient de personnel provenant d’au moins trois disciplines de la santé (y compris au moins une spécialité médicale) et offraient et intégraient ces services au sein de l’unité. Les directeurs administratifs des UMTD admissibles ont été invités à remplir un questionnaire détaillé sur leur infrastructure et leurs activités cliniques, administratives, de recherche et d’enseignement.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 102 UMTD ont remis le questionnaire rempli. Les généralistes, les anesthésistes et les physiatres étaient les médecins participant le plus aux UMTD (56 %, 51 % et 32 %, respectivement). Les physiothérapeutes, les psychologues et les infirmières étaient les principaux professionnels non médecins au sein de ces UMTD (75 %, 68 % et 57 %, respectivement), mais de 33 % à 56 % d’entre eux travaillaient à temps partiel. Seulement 77 % des UMTD tenaient des réunions interdisciplinaires régulières pour discuter de la prise en charge des patients, et 32 % disposaient d’un psychologue ou d’un psychiatre. Les trois services les plus dispensés par les physiothérapeutes étaient l’évaluation des patients, la physiothérapie ou les exercices individuels et la stimulation nerveuse électrique transcutanée. Les trois services les plus dispensés par les psychologues étaient la thérapie individuelle, la thérapie cognitivo-comportementale et la thérapie psychodynamique. Le principal rôle des infirmières consistait à évaluer les patients, à assurer l’assistance pendant les interventions et à éduquer les patients.

CONCLUSION :

Divers professionnels de la santé jouent divers rôles importants au sein des UMTD du Canada. Cependant, ils sont rares à le faire à temps plein, et la profondeur de l’évaluation et du traitement de la douleur dans un contexte purement multidisciplinaire est contestable.

Chronic pain is a significant health problem that affects one in five adults (1–3) and is a common problem in children (4,5). Chronic pain profoundly affects all aspects of the quality of life of the sufferer, including physical, psychological and social well-being (6–8). Furthermore, there are tremendous direct and indirect costs to the individual and to society as a whole from chronic pain (9,10).

Because of the complexity of chronic pain, no single discipline has the expertise to assess and manage it independently. Because of the deleterious consequences of chronic pain on the patient’s psychosocial and physical functioning (6–8), a multidisciplinary team approach is considered to be the optimal therapeutic paradigm for most pediatric and adult chronic pain sufferers (11,12). Multidisciplinary chronic pain teams are necessary to adequately treat complex chronic pain conditions to ensure that assessments and interventions are tailored to the needs of the individual patient, rather than being focused on the underlying disease or condition (13). Furthermore, given that complex chronic pain conditions have multiple causes, patients must be treated from a comprehensive multimodal rehabilitation perspective that focuses on providing education, skills training, and application or relapse training (11,12). Multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (MPTF) provide patients with an opportunity to achieve both adequate pain relief and improved physical, behavioural and psychological functioning.

Many studies have examined the effectiveness of multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment programs with conflicting evidence regarding improvements in domains of quality of life (eg, physical, psychological, role and social functioning) (14–17). Several systematic and meta-analytic reviews have also been conducted to synthesize the literature on this issue (11,18). Despite evidence of their effectiveness, the authors of these studies noted that the multidisciplinary pain programs were not standardized in their treatment philosophy or regimen, or the essential disciplines that should be part of these programs. Little is known about MPTF in Canada and the role health care professionals play in these facilities (19). The objective of the present study was to describe and analyze the roles of different health care professionals in all MPTF in Canada and how they are integrated in these facilities.

METHODS

Selection and description of participants

In the present study, a MPTF was defined as a health care delivery facility staffed with health care professionals who specialized in the diagnosis and management of patients with chronic pain. To be included in the study, the MPTF had to advertise itself as a pain clinic or a pain centre, and/or a centre offering specialized multidisciplinary services for the diagnosis and management of patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. It must also have employed staff from a minimum of three different health care disciplines (whose services were available and integrated within the pain clinic or centre), including at least one medical specialty. When the health care professionals worked in the same facilities of the MPTF, they were referred to as ‘integrated’ in the present study.

This definition was different from that defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), which stated that the MPTF should be staffed by at least two physicians from two different specialties and one additional medical professional who is either a psychiatrist or psychologist (13). In an investigators’ planning meeting, which involved the participation of directors and representatives from various pain clinics in Canada, the consensus was that the IASP definition was too restrictive, and its application would exclude a large number of clinics that used a multidisciplinary treatment approach in Canada. Thus, we adopted a different definition in the present study.

Search strategy

Because there was no complete pre-existing list of MPTF in Canada, a comprehensive search strategy was used to locate all existing MPTF. To identify hospital-based MPTF, letters were sent to the medical directors and/or chief executive officer of all hospitals and rehabilitation centres across Canada. The letters inquired whether there was a pain clinic or a pain centre within their institution. If yes, they were asked to provide the name of the director and contact information of the clinic. Nonhospital-based or private clinics were identified by contacting compensation agencies (for work or motor vehicle accidents), the Insurance Bureau of Canada and pharmaceutical industries. The information was further supplemented with clinics identified through Web sites. Then, a preliminary list was made available to the study representatives in each province (provincial representatives), who were pain clinicians or researchers with an excellent knowledge of the pain clinics and centres in their provinces. Each provincial representative screened the pain clinics from the preliminary list to ensure the clinic’s eligibility based on the definition of MPTF described above.

Technical information

With Research Ethics Board approval, the directors of the potential MPTF were contacted by regular or electronic mail with invitation letters along with the survey questionnaires. If the questionnaires were not received within three weeks after mailing, the directors were reminded by mail or telephone contact. They were also contacted if the questionnaires were not completed properly.

The survey questionnaire used in the present study was adapted from the Quebec Chronic Pain Clinic Survey (20). The questionnaire covered the organizational structure of the MPTF; clinical activities such as the volume of patients, wait lists, the spectrum of chronic pain conditions treated and treatment modalities offered or available within the institution; staff composition and availability; teaching and research activities; and the type of funding for services and overhead. Data were collected from June 2005 to February 2006.

Statistics and data presentation

Only the data pertaining to composition and the roles of health care professionals within the MPTFs are presented (using standard descriptive statistics). A description of the other characteristics of different MPTF has been published elsewhere (21,22).

RESULTS

A total of 120 pain treatment facilities met the study selection criteria for MPTF, and 85% of them completed and returned the survey questionnaire.

Characteristics of multidisciplinary chronic pain teams

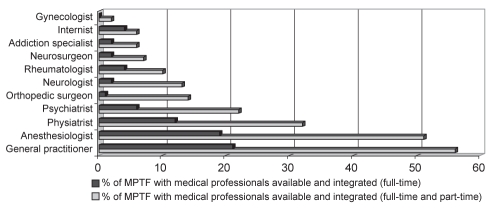

A wide variety of medical disciplines comprised the chronic pain teams as outlined in Figure 1. General practitioners, anesthesiologists and physiatrists were the most common types of physicians integrated in the MPTF (56%, 51% and 32%, respectively). Only one in five MPTF were staffed with a psychiatrist. As shown in Figure 1, most of the medical staff worked on a part-time basis. Full-time staff were defined as staff working in the MPTF for at least four days per week. The composition of physicians is shown in Table 1; the composition of physicians in each province is shown in Figure 2. Most of the provinces showed a balanced composition of physicians from different specialties. Anesthesiologists were most prevalent in the MPTF in the Atlantic provinces, while general practitioners were most prevalent in the western provinces, such as Saskatchewan.

Figure 1).

Medical professional involvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (MPTF). The figure shows the percentage of MPTF staffed with physicians of different specialties, either working full-time (four days or more per week) or full-time and part-time

Table 1.

Physicians available and integrated in each multidisciplinary pain treatment facility

| Physician | Full-time (range) | Full-time and part-time (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiologist | 0 (0–6) | 1 (0–9) |

| Neurologist | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–3) |

| Rheumatologist | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–4) |

| PMR | 0 (0–16) | 0 (0–16) |

| Family physician | 0 (0–18) | 1 (0–18) |

| Gynecologist | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–3) |

| Neurosurgeon | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–4) |

| Orthopedic surgeon | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–3) |

| Internist | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Psychiatrist | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) |

| Addiction specialist | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

The number of physicians is expressed as the median. PMR Specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation

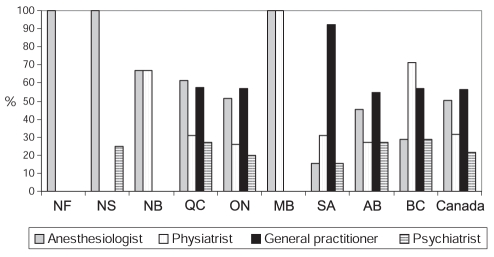

Figure 2).

Proportion of physician involvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (MPTF) by province. The figure shows the percentage of MPTF in each province staffed with the four different types of medical professionals – anesthesiologists, physiatrists, general practitioners and psychiatrists. AB Alberta; BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NF Newfoundland; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; QC Quebec; SA Saskatchewan

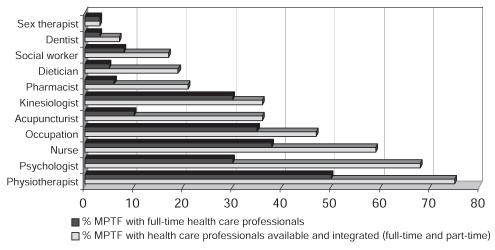

The representation of other health care professionals that worked as full-time staff or were integrated in MPTF (either full-time or part-time) is shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. The most common nonphysician professionals were physiotherapists, psychologists and nurses (75%, 68% and 57% of MPTF, respectively), but only 67%, 44% and 67%, respectively, were working full-time. Only seven MPTF offered integrated services from dental specialists, who were also available but not integrated in another 27 MPTF. One facility was run by dental specialists. Thirty-five per cent had acupuncturists integrated into their chronic pain teams. A variety of nonclinician health care professionals not listed in the questionnaire were identified by the respondents as members of their pain teams. These nonclinician health professionals included massage therapists, counsellors, recreational specialists and chiropractors. These professionals were available or integrated in 3% to 5% of MPTF.

Table 2.

Nonphysician health care professionals available and integrated in each multidisciplinary pain treatment facility

| Health professional | Full-time (range) | Full-time and part-time (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing | 0 (0–8) | 1 (0–8) |

| Psychologist | 0 (0–5) | 1 (0–5) |

| Social worker | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| Sex therapist | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Physiotherapist | 0 (0–15) | 1 (0–15) |

| Kinesiologist | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–7) |

| Occupation therapist | 0 (0–20) | 0 (0–20) |

| Acupuncturist | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) |

| Pharmacist | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) |

| Dietician | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| Dentist | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–6) |

The number of nonphysician health care professionals is expressed as the median

Figure 3).

Health care professionals involved in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (MPTF). When health care professionals worked more than four days per week in the MPTF, they were defined as full-time staff

The services provided by the various health care professionals varied. The three most frequent services provided by physiotherapists were patient assessment, individual physiotherapy or exercise and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. The three most common services provided by psychologists were individual counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy. The major roles of nurses were patient assessment, assisting in interventional procedures and patient education.

Only 77% of MPTF held regular multidisciplinary meetings to discuss clinical cases. More than one-half of the MPTF held those meetings at least once per week (once per week, 28%; more than once per week, 25%). When applying the IASP criteria for the definition of MPTF, only 39 of the Canadian MPTF were eligible. Thirty-three of the MPTF were staffed with either a full-time psychologist or psychiatrist.

DISCUSSION

The present survey is the first comprehensive national study of the clinical activities and infrastructure of MPTF. Anesthesiologists and general practitioners were the most frequent types of physicians in MPTF and the majority of the other health care team members were comprised of physiotherapists, psychologists and nurses.

The multidisciplinary approach is considered the optimal therapeutic paradigm for the management of chronic pain patients (11,18). However, the present survey revealed that not all MPTF used a multidisciplinary approach in which all members of the team were truly integrated. Although multidisciplinary treatment requires having more than two health care providers from different disciplines under the same roof, it may not always mean that the pain condition is treated in an integrated manner. We would argue that the ideal treatment approach is ‘interdisciplinary’. An interdisciplinary approach is characterized by a variety of disciplines working together in the same facility in an integrated manner with joint treatment goals and coordinated interventions that are facilitated by ongoing communication among members of the health care team (23,24). Based on our survey results, not all the MPTF were working in an interdisciplinary manner because only 77% of the MPTF reported that they held regular meetings to discuss patient assessment or treatment plans (21). The members of the treatment team must communicate with each other on a regular basis, both about specific patients and overall development. Health care services in a multidisciplinary pain clinic must be integrated, and based on multidisciplinary assessment and management of the patient. The psychological aspect is an important facet of the overall management, but only one-third of the MPTF were staffed with either a psychologist or a psychiatrist. Because psychology services are not routinely covered by provincial health care insurance, there are cognitive behavioural programs, mindfulness stress reduction programs and counselling services run by family physicians, physiotherapists and occupational therapists in Canada. Clearly, funding for mental health specialists in MPTF is needed.

Among various medical specialties in the multidisciplinary team, general practitioners and anesthesiologists were most commonly integrated in the MPTF. Anesthesiologists played an important role in the early development of chronic pain medicine. This is because neural blockade was used widely for the treatment of a variety of acute and chronic pain syndromes (25). Ever since John Bonica revolutionized chronic pain management with the concept of multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic endeavours, anesthesiologists have remained an important component of the multidisciplinary team (26). A recent national survey of anesthesiologists showed that 38% of the respondents were involved in chronic pain management. Of those, 26% were affiliated with a multidisciplinary clinic (27). Other than the use of interventional techniques, anesthesiologists play a crucial role in the pharmacological management of chronic pain to achieve adequate pain relief and improvements in sleep, mood and exercise tolerance.

The goals of MPTF are to improve or restore function, alleviate pain whenever possible, and facilitate adaptive problem solving, communication and coping skills. Therefore, the treatment offered in these centres must address not only the clinical symptoms and experience of pain, but also any associated distress, dysfunction and disability. Given these goals, it is not surprising that physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists and nurses were found to be the key members in Canadian MPTF. Chronic pain often leads to the avoidance of physical activity due to fear of reinjury or because it exacerbates the pain. Therefore, physical therapy is often the cornerstone of treatment for many complex chronic pain problems. In addition to providing physical therapy, physiotherapists and occupational therapists also conduct functional assessments, various types of structured exercise programs such as ‘back school’, and provide counselling to chronic pain patients.

Nursing also plays an important role in the MPTF. Given the complexity of care required, nurses are often instrumental in coordinating care and helping patients navigate the health care system to obtain the needed services. The roles include evaluation and assessment of pain patients, supervision of medication titration, education of patients, conducting non-pharmacological therapy such as biofeedback and relaxation strategies, and involvement in research.

An important factor in improving psychosocial well-being of patients with chronic pain is to enhance their self-efficacy and perceived ability to control or manage their pain. This is often accomplished through techniques that help change the patient’s thoughts, feelings and beliefs about their pain, which is commonly referred to as CBT. CBT is often organized into a program of therapy that is delivered by various members of the chronic pain team, but most commonly by psychologists. The content of the programs varies across clinics but usually includes coping skills, positive reinforcement for nonpain behaviour, cognitive reframing, education and self-management strategies (28). The goal of these psychological therapies is to make the patient’s life as normal as possible by helping them learn strategies for taking control back from the pain. In addition, many patients with chronic pain suffer from anxiety and depression, and can benefit from psychotherapy provided by psychiatrists or psychologists.

CONCLUSION

The majority of MPFT in Canada involve a wide variety of health care professionals, but not all of them function in an integrated, interdisciplinary manner. Given the movement toward more truly integrated centres, it is important for health care professionals to be trained in ways that promote interdisciplinary collaboration in regard to the treatment of chronic pain.

Footnotes

FUNDING: The present study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (via the CIHR/Rx&D Collaborative Research Program) in partnership with Pfizer Canada and the three networks of the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (Santé buccodentaire, Adaption-réadaption, Neurosciences et santé mentale).

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada Health Indicators<http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82-221-XIE/01002/toc.htm> (Version current at November 20, 2008).

- 2.Moulin DR, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada – prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manage. 2002;7:179–84. doi: 10.1155/2002/323085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Squire P, Cui E, Horbay GLA. Chronic pain in Canada: Have we improved our management of chronic noncancer pain? Pain Res Manage. 2007;12:39–47. doi: 10.1155/2007/762180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, Hunfeld JAM, Bohnen AM, van Sujlekom-Smit LWA, Passchier J. Pain in children and adolescents: A common experience. Pain. 2000;87:51–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dijk A, McGrath PA, Pickett W, VanDenKerkhof EG. Pain prevalence in nine-to 13-year-old school children. Pain Res Manage. 2006;111:234–40. doi: 10.1155/2006/835327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker N, Bondegaard TA, Olsen AK, Sjogren P, Bech P, Eriksen J. Pain epidemiology and health related quality of life in chronic nonmalignant pain patients referred to a Danish multidisciplinary pain center. Pain. 1997;73:393–400. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: A World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konijnenberg AY, Uiterwaal CS, Kimpen JL, van der Hoeven J, Buitelaar JK, de Graeff-Meeder ER. Children with unexplained chronic pain: Substantial impairment in everyday life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:680–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.056820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maniadakis N, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain. 2000;84:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleed M, Eccleston C, Beecham J, Knapp M, Jordan A. The economic impact of chronic pain in adolescence: Methodological considerations and a preliminary cost-of-illness study. Pain. 2005;119:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ospina M, Harstall C.Multidisciplinary Pain Programs for Chronic Pain: Evidence from Systematic Reviews<http://www.ihe.ca/documents/multi_pain_programs_for_chronic_pain.pdf> (Version current at November 20, 2008).

- 12.Stinson JN. Complex chronic pain in children, interdisciplinary treatment. In: Schmidt RF, Willis WD, editors. Encyclopedic Reference of Pain. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Task Force on Guidelines for Desirable Characteristics for Pain Treatment Facilities, IASP. Desirable characteristics for pain treatment facilities. <http://www.iasp-pain.org/desirabl.html> (Version current at August 12, 2006).

- 14.Fishbain DA, Lewis J, Cole B, et al. Multidisciplinary pain facility treatment outcome for pain-associated fatigue. Pain Med. 2005;6:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joos B, Uebelhart D, Michel BA, Sprott H. Influence of an outpatient multidisciplinary pain management program on the health-related quality of life and the physical fitness of chronic pain patients. Biomedicine. 2004;3:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitahara M, Kojima KK, Ohmura A. Efficacy of interdisciplinary treatment for chronic nonmaligant pain patients in Japan. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:647–55. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210909.49923.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins H, Gatchel RJ, Noe C, et al. A prospective one-year outcome study of interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Compromising its efficacy by managed care policies. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:156–62. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000058886.87431.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk D. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centres: A meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49:221–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agence d’évaluation des technologies et des modes d’intervention en santé (AETMIS) Management of Chronic (Non-Cancer) Pain: Organization of Health Services (AETMIS 06-04) Montréal: AETMIS; 2006. pp. xv–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veillette Y, Dion D, Altier N, Choinière M. The treatment of chronic pain in Québec: A study of hospital-based services offered within anesthesia departments. Can J Anesth. 2005;52:600–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03015769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, et al. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Can J Anesth. 2007;54:977–68. doi: 10.1007/BF03016631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng P, Stinson J, Choiniere M, et al. Dedicated multidisciplinary pain management centers for children in Canada: The current status. Can J Anesth. 2007;54:985–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03016632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark TS. Interdisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: Is it worth the money? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2000;13:240–3. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2000.11927682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardea MA, Gatchel RJ. Interdisciplinary treatment of chronic pain. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:18–23. doi: 10.1007/s11916-000-0005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haddox JD, Bonica JJ. Evolution of the specialty of pain medicine and the multidisciplinary approach to pain. In: Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, editors. Neural Blockade in Clinical Anesthesia and Management of Pain. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 1113–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson P. Comprehensive pain rehabilitation program: A North American perspective. In: Jensen TS, Wilson PR, Rice ASC, editors. Clinical Pain Management: Chronic Pain. 1st edn. London: Arnold; 2003. pp. 163–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng P, Castano E. Survey of chronic pain practice by anesthesiologists in Canada. Can J Anesth. 2005;52:383–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03016281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eccleston C. Role of psychology in pain management. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:144–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]