Abstract

We characterized peptidyl hydroxyproline (Hyp) O-galactosyltransferase (HGT), which is the initial enzyme in the arabinogalactan biosynthetic pathway. An in vitro assay of HGT activity was established using chemically synthesized fluorescent peptides as acceptor substrates and extracts from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) T87 cells as a source of crude enzyme. The galactose residue transferred to the peptide could be detected by high-performance liquid chromatography and matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry analyses. HGT required a divalent cation of manganese for maximal activity and consumed UDP-d-galactose as a sugar donor. HGT exhibited an optimal pH range of pH 7.0 to 8.0 and an optimal temperature of 35°C. The favorable substrates for the activity seemed to be peptides containing two alternating imino acid residues including at least one acceptor Hyp residue, although a peptide with single Hyp residue without any other imino acids also functioned as a substrate. The results of sucrose density gradient centrifugation revealed that the cellular localization of HGT activity is identical to those of endoplasmic reticulum markers such as Sec61 and Bip, indicating that HGT is predominantly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. To our knowledge, this is the first characterization of HGT, and the data provide evidence that arabinogalactan biosynthesis occurs in the protein transport pathway.

O-glycosylation is the addition of a sugar to hydroxy amino acids such as Thr, Ser, Hyp, Hyl, or Tyr (Lehle et al., 2006). This type of protein modification occurs in many organisms to modify a large variety of proteins. Several types of sugars can be linked to proteins via O-glycosylation, including Man, N-acetylgalactosamine, Glc, Xyl, N-acetylglucosamine, Fuc, Gal, and arabinofuranose (Araf). In addition, elongation of the added sugar residues yields a large variety of oligo- and polysaccharide extensions on the substrate proteins. These modifications are known to play important roles in various phenomena, including pathways required to maintain biological systems and basic cellular functions.

Structural analysis of oligo- and polysaccharides in plant cell walls has revealed the presence of three types of O-linked structures, Gal-O-Hyp, Araf-O-Hyp, and Gal-O-Ser (Kieliszewski and Shpak, 2001; Seifert and Roberts, 2007). A part of these three structures has been found on proteins in the super family that includes arabinogalactan protein (AGP) and extensin, which are localized to the cell surface. AGPs contain O-linked arabinogalactan oligo- or polysaccharides attached to Hyp residues (Gal-O-Hyp). It is known that arabinogalactan polysaccharides mainly consist of β-1,3 linkages of Gal polymers (Seifert and Roberts, 2007). Extensin contains short arabino-oligosaccharide chains attached to Hyp residues (Araf-O-Hyp) and single Gal residues linked to Ser residues (Gal-O-Ser). It has been suggested that these O-linked structures play an important role in many stages of growth and development in plants, including signaling, embryogenesis, and programmed cell death (Knox, 2006; Seifert and Roberts, 2007). However, our understanding of the biosynthesis of these O-linked structures is limited at present.

Shpak et al. described a novel strategy to elucidate O-glycosylation of AGPs via introduction of synthetic genes encoding a protein substrate of glycosyltransferases into plant cells (Shpak et al., 1999; Estevez et al., 2006). This strategy provided good evidence for the substrate specificities of Hyp O-galactosyltransferase (HGT). Hyp galactosylation occurs on clustered noncontiguous Hyp residues such as Xaa-Hyp-Xaa-Hyp repeats of AGPs (where Xaa is any amino acid except Hyp; Tan et al., 2003). However, the arabinogalactosylation site is not limited to clustered noncontiguous Hyp residues, as isolated Hyp residues with appropriate surrounding sequences can be modified with arabinogalactan (Matsuoka et al., 1995; Shimizu et al., 2005). Therefore, the mechanism of glycosylation to Hyp residues seems complex in plants, while we have little information about the glycosyltransferase(s) involved in arabinogalactan biosynthesis. To examine the enzymatic properties and to identify genes involved in arabinogalactan biosynthesis, we first attempted to establish an in vitro assay for HGT activity, which catalyzes the initial step in arabinogalactan biosynthesis in plants.

Here, we report a novel assay for HGT activity based on the use of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-enriched cell lysates extracted from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) T87 cells as a source of the enzyme and chemically synthesized fluorescent peptides as enzyme substrates. The method enabled us to characterize the enzymatic properties of HGT and to determine the localization of HGT in Arabidopsis cells. Properties of the enzyme and the usefulness of our assay for various studies are discussed.

RESULTS

In Vitro Assay for HGT Activity

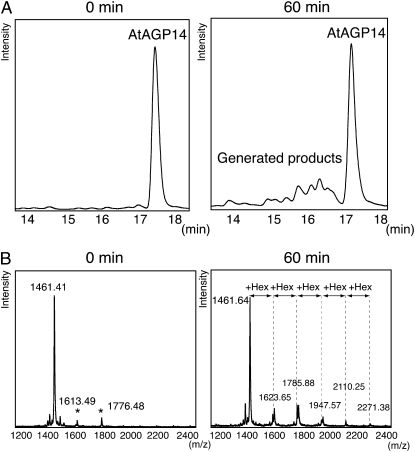

To study the biosynthesis of arabinogalactan, we first attempted to establish an in vitro assay for the activity of HGT, the initial enzyme in arabinogalactan biosynthesis, using chemically synthesized peptides and extracts from Arabidopsis T87 cells. AtAGP14 (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus: At5g56540) is one of the smallest AGPs and contains a signal sequence and glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor attachment signal sequence at its N terminus and C terminus, respectively (Schultz et al., 2004). We designed a peptide based on the AtAGP14 sequence (VDAOAOSOTS; Mr 1,462.6) as a substrate. The peptide lacks the signal sequences for secretion and glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor attachment that are present in the full-length AtAGP14 protein. The substrate peptides were chemically synthesized with two modifications at the N terminus; namely, addition of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to facilitate detection of the peptide and addition of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) as a spacer (Table I). Arabinogalactan synthetic activity was measured using 100 μm AtAGP14 peptide as an acceptor, 5 mm UDP-Gal as a donor, 1 mm MnCl2 as a cofactor, and microsomal fractions as a source of crude enzyme. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 60 min, heated at 95°C for 3 min to stop the reaction, and then subjected to HPLC using a reverse-phase column. The FITC-labeled peptide was detected using a fluorescence detector. Several additional peaks from 14.5 to 18.0 min were detected (Fig. 1A, right section). Next, we collected the product and substrate peaks (14.5–18.0 min), and analyzed their Mrs by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS). The MALDI-TOF-MS spectrum included a peak corresponding to the mass of the AtAGP14 peptide (1,461.64) and five additional peaks were detected at mass values of 1,623.65, 1,785.88, 1,947.57, 2,110.25, and 2,271.38. The mass differences for each peak were 162.23, 161.69, 162.68, and 161.13, which correspond to the mass of a deoxyhexosyl group (162.2), suggesting that up to five Gal residues were attached to the Hyp and/or Ser residue of the AtAGP14 peptide.

Table I.

Synthetic peptides used in this study

| Peptide | Sequence | Mr |

|---|---|---|

| AtAGP14 | FITC-gaba-VDAOAOSOTS | 1,462.6 |

| AtAGP14-A | FITC-gaba-VDAOAOAOAA | 1,401.3 |

| AtAGP14-1 | FITC-gaba-VDAOAPAOAA | 1,385.5 |

| AtAGP14-2 | FITC-gaba-VDAAAOAOAA | 1,359.5 |

| AtAGP14-3 | FITC-gaba-VDAOAAAOAA | 1,359.5 |

| AtAGP14-4 | FITC-gaba-VDAAAOAAAA | 1,317.4 |

| AtAGP14-5 |

FITC-gaba-VDAAAOOOAA |

1,401.5 |

Figure 1.

In vitro assay for arabinogalactan synthetic activity of plant cells. A, HPLC analysis of reaction products using AtAGP14 peptide as an acceptor. Reaction mixtures were incubated with microsomal fractions for 0 min (left section) or 60 min (right section). B, MALDI-TOF-MS analysis of reaction products using AtAGP14 peptide as an acceptor. Peptides collected from 17 to 18 min (AtAGP14; left section) or from 14.5 to 17 min (generated products; right section) as shown in Figure 1A, as analyzed here by MALDI-TOF-MS. Asterisks indicate no O-hexosylated peaks. Hex, Hexose.

Although promising, the method still has two potential problems for measuring HGT activity. First, it is theoretically possible that Gal residues were attached to a Ser residue, as the AtAGP14 acceptor peptide contains a Ser residue in addition to Hyp residues. Second, it is possible that the results reflect the elongation reaction step in arabinogalactan biosynthesis rather than a first-addition step. Therefore, we attempted to improve the in vitro assay for HGT activity by addressing these issues.

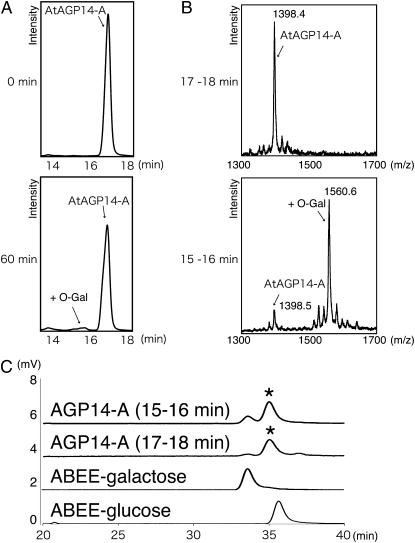

To do this, we designed another peptide AtAGP14-A (VDAOAOAOAA; O: Hyp; Mr 1,401.3), in which two Ser residues and one Thr residue were replaced by Ala residues to exclude the potential for transfer of Gal to Ser. We then prepared three different subcellular fractions from T87 cells: P10 (ER-enriched), P100 (Golgi-enriched), and S100 (cytosolic) fractions. HGT activity was assayed using 100 μm AtAGP14-A peptide as an acceptor, 5 mm UDP-Gal as a donor, 1 mm MnCl2 as a cofactor, and the P10, P100, or S100 fraction as a source of crude enzyme (Fig. 6A). An additional peak appeared at 15.5 min only when the P10 was used for the reaction, but not when the P100 or S100 was used for the reaction (data not shown), suggesting that the observed peak is an O-galactosylated product of AGP14-A (Fig. 2A) and that HGT activity is present in the P10 fraction of Arabidopsis cells.

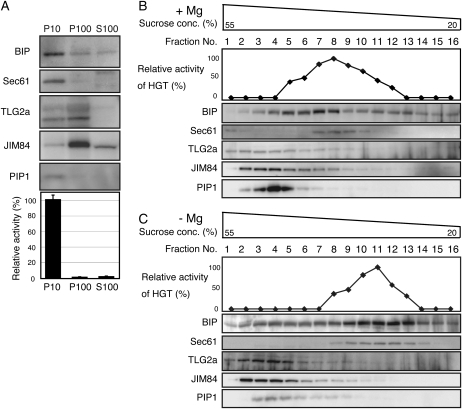

Figure 6.

Subcellular localization of Arabidopsis HGT activity. A, Subcellular fractionation of HGT. Total protein extract (excluding cell debris) was prepared from T87 cells as described in “Materials and Methods.” B and C, Suc density gradient centrifugation in the presence (B) or absence (C) of Mg2+. After centrifugation, each resulting gradient was separated into 16 fractions. Anti-AtTLG2a and JIM84 antibodies were used to detect markers for the Golgi apparatus, anti-Sec61 and Bip were used to detect markers for the ER, and anti-PIP1 was used to detect a marker for the plasma membrane.

Figure 2.

In vitro assay for HGT activity of plant cells. A, HPLC analysis of reaction products using AtAGP14-A peptide as an acceptor. Reaction mixtures were incubated with the P10 fraction for 0 min (top section) or 60 min (bottom section). B, MALDI-TOF-MS analysis of reaction products using AtAGP14-A peptide as an acceptor. Peptides collected from 15 to 16 min (products, +O-Gal) or from 17 to 18 min (AtAGP14-A) as shown in Figure 2A were analyzed here by MALDI-TOF-MS. C, Monosaccharide analysis of reaction products using AtAGP14-A peptide as an acceptor. Peptides collected from 15 to 16 min (products, +O-Gal) or from 17 to 18 min (AtAGP14-A) in Figure 2B were purified and approximately 300 pmol each was hydrolyzed by 4 m TFA. The acid-hydrolyzed products were labeled with ABEE and were analyzed by HPLC using a C18 column. ABEE-Gal and ABEE-Glc eluted at 33.9 min and 35.6 min under the conditions, respectively. Asterisks indicate a nonspecific peak that eluted at 35.3 min in both samples from 15 to 16 min (products, +O-Gal) or from 17 to 18 min (AtAGP14-A).

To confirm that the product is an O-galactosylated AGP14-A, we collected the corresponding product peak (from 15–16 min) and the AtAGP14-A substrate peak (from 17–18 min), then analyzed their Mrs by MALDI-TOF-MS (Fig. 2B). The MALDI-TOF-MS spectrum showed that the masses of the AtAGP14-A substrate and product were 1,398.4 and 1,560.6, respectively. Thus, the mass difference between the AtAGP14-A substrate and the product was 162.2 D, which corresponds to the mass of a deoxyhexosyl group, suggesting that the product is indeed an O-glycosylated peptide. Under the reaction condition that was used, no peaks of mass higher than 1,560.6 were detected, indicating that only one hexose residue was attached to the AtAGP14-A peptide when the P10 fraction was used as the source for the enzyme. To identify the hexose species, we performed monosaccharide analysis using a p-aminobenzoic acid ethylester (ABEE)-labeled sugar derivative after the acid hydrolysis of the reaction product, followed by the HPLC analysis (Fig. 2C). The hydrolysis product from product peak (from 15–16 min) showed the ABEE-Gal peak alone. On the contrary, the ABEE-Gal peak was not detected in the hydrolysis product from the AtAGP14-A substrate peak (from 17–18 min; Fig. 2C), indicating that the hexose residue that is attached to the Hyp residue is actually Gal. This shows that the method is suitable to measure HGT activity, as it does not detect the elongation activity.

Requirement of HGT Enzymatic Activity for Cofactors

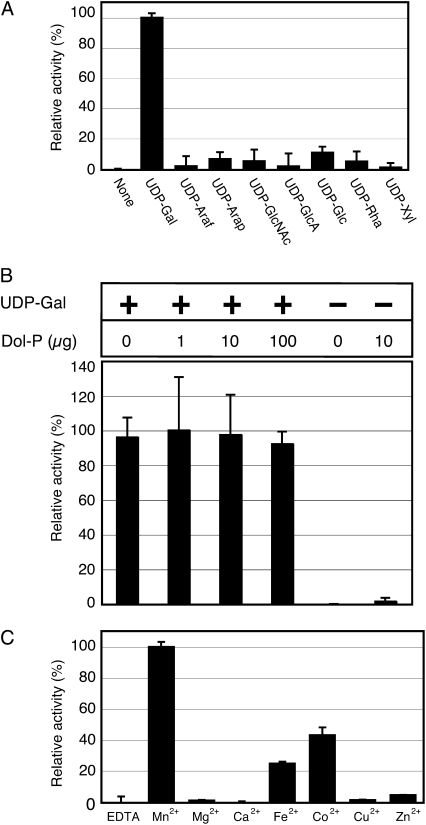

Most glycosyltransferases utilize nucleotide sugars or dolichyl-P (Dol-P) sugars as donors. To determine which sugar donors can be utilized in the HGT reaction, we examined if O-galactosylation can occur via consumption of UDP-d-Gal as a donor. Various UDP-sugars (UDP-d-Gal, UDP-l-Araf, UDP-l-arabinopyranose, UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, UDP-d-GlcUA, UDP-d-Glc, UDP-l-Rha, and UDP-d-Xyl) were added to the reaction mixture and the amount of O-galactosylated product of AtAGP14-A substrate was measured. The highest HGT activity was detected when UDP-d-Gal was used as a donor, indicating that HGT activity requires UDP-d-Gal to transfer a Gal residue to the acceptor substrate, either directly or indirectly (Fig. 3A). When UDP-d-Glc was used as a donor, the HGT activity could also be detected weakly. It is known that UDP-Glc/UDP-Gal 4-epimerase converts UDP-d-Glc to UDP-d-Gal (Barber et al., 2006). Therefore it is quite likely that HGT uses the converted UDP-d-Gal when UDP-d-Glc was used as a donor in vitro. The effect of Dol-P on HGT activity was also investigated. To do this, different amounts of Dol-Ps (1, 10, and 100 μg) were added to the reaction mixture. However, none of the Dol-P concentrations we tested increased HGT activity, suggesting that Dol-P-d-Gal is not used as a sugar donor in the HGT reaction (Fig. 3B). The effect of the presence of several divalent cations on enzyme activity was also tested (Fig. 3C). Each cation was studied at a fixed concentration (1 mm). The HGT enzyme was inactive in the absence of divalent cations (i.e. in the presence of 1 mm EDTA), whereas HGT activity can be detected in the presence of Mn2+ and Co2+ cations, indicating that HGT requires Mn2+ for maximal activity (Fig. 3C). Taken together, the results show that UDP-d-Gal and Mn2+ are required for the optimal HGT activity.

Figure 3.

Enzymatic properties of HGT. A, Sugar nucleotide requirement of HGT. Reaction mixtures were incubated with or without various UDP sugars. One hundred percent corresponds to incorporation of 1.33 × 10−1 unit (pmol/min/μg) with UDP-d-Gal. Results are plotted as mean ± sd from three independent experiments. B, Influence of Dol-P on HGT activity. Reaction mixtures were incubated with or without Dol-P. One hundred percent corresponds to incorporation of 6.83 × 10−2 unit (pmol/min/μg) with UDP-d-Gal and Dol-P (1 μg). Results are plotted as mean ± sd from three independent experiments. C, Metal cation requirement of HGT. Reaction mixtures were incubated with EDTA or various divalent metals. One hundred percent corresponds to incorporation of 1.98 × 10−1 unit (pmol/min/μg) with manganese. Results are plotted as mean ± sd from three independent experiments.

Effects of Temperature and pH on HGT Activity

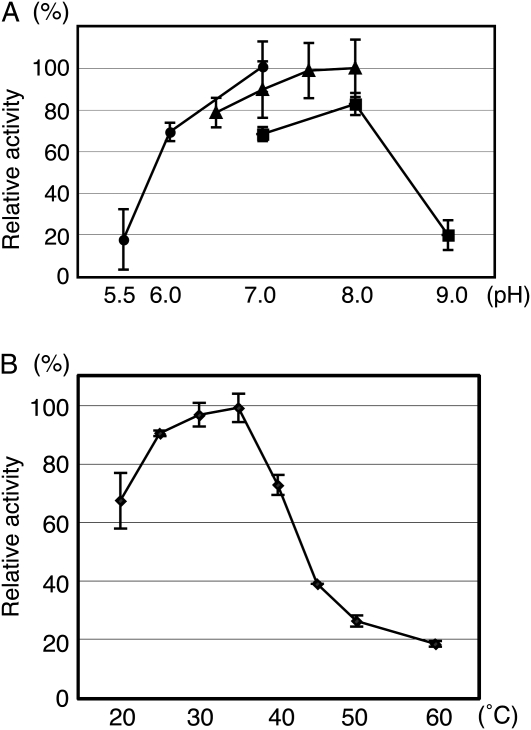

We next determined the optimal pH and temperature ranges for HGT activity. To do this, we first monitored enzyme activity over a range of pH values. Three types of pH buffer, 100 mm MES-NaOH (pH 5.5, 6.0, and 7.0), 100 mm MOPS-NaOH (pH 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0), and 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0), were tested. The P10 fraction (6 μg) was used at 30°C for 60 min and the reactions were stopped by heat treatment (95°C) for 3 min. The highest enzyme activity was observed in 100 mm MES-NaOH buffer, pH 7.0. The pH conditions permissive for HGT activity exhibited a broad optimum from pH 7.0 to pH 8.0 (Fig. 4A). Enzyme activity was also measured at different temperatures. The P10 fraction (6 μg) was incubated at a series of temperatures (20°C, 25°C, 30°C, 35°C, 40°C, 45°C, 50°C, and 60°C) with AtAGP14-A peptide for 60 min and the reaction was stopped by heat treatment (95°C) for 3 min. The optimal temperature for activity was 35°C and the results suggest that the enzyme is relatively active in a broad temperature range, from 20°C to 40°C (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Optimal temperature and pH ranges for HGT activity. A, Effects of temperature on HGT enzymatic activity. The buffer used was 100 mm MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0). One hundred percent corresponds to incorporation of 1.65 × 10−1 unit (pmol/min/μg) at 35°C. Results are plotted as mean ± sd from three independent experiments. B, Effects of pH on HGT enzymatic activity. The buffers used were 100 mm MES-NaOH (circle), 100 mm MOPS-NaOH (triangle), or 100 mm Tris-HCl (square). One hundred percent corresponds to incorporation of 5.63 × 10−2 unit (pmol/min/μg) at pH 8.0 of 100 mm MOPS-NaOH. Results are plotted as mean ± sd from three independent experiments.

Substrate Specificity of HGT

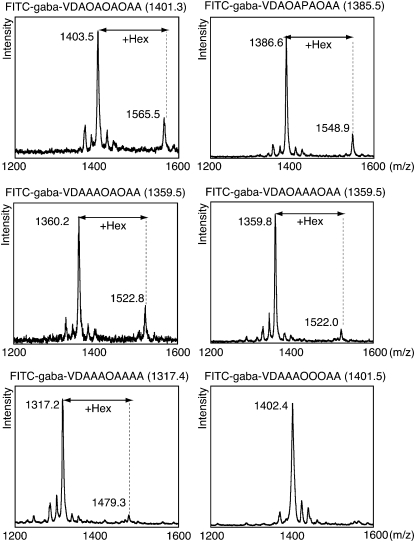

To investigate the influence of amino acids neighboring the Hyp residue in the substrate peptide on HGT activity, we tested various sequence versions of the synthesized peptide as potential substrates (Table I). The reaction products were separated and collected by HPLC and their Mrs were analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS. AtAGP14-A (FITC-gaba-VDAOAOAOAA), AtAGP14-1 (FITC-gaba-VDAOAPAOAA), AtAGP14-2 (FITC-gaba-VDAAAOAOAA), AtAGP14-3 (FITC-gaba-VDAOAAAOAA), and AtAGP14-4 (FITC-gaba-VDAAAOAAAA) could be acceptors, suggesting that HGT can transfer a Gal residue to Hyp residues located in polypeptide sequences in vivo (Fig. 5). On the contrary, AtAGP14-5 (FITC-gaba-VDAAAOOOAA) was not an acceptor of HGT activity in the assay, suggesting that the contiguous Hyp residues cannot act as an acceptor of HGT (Fig. 5). Among the active substrate peptides that we found above, peptides contain two or more alternate imino acids, such as AtAGP14-A, AtAGP14-1, and AtAGP14-2 seemed better substrates than which did not contain such sequence (AtAGP14-3, AtAGP14-4) as MS peaks with Gal showed higher in the former three peptides than the other two. This observation suggested that higher order of substrate peptide affects the preference of HGT although we cannot rule out a possibility that the difference was a result of the difference of ionization efficiency of peptides.

Figure 5.

Effects of amino acids neighboring Hyp acceptor residues on HGT activity. Effects of amino acids near Hyp residues on HGT activity were tested in the standard assay (see “Materials and Methods”) at a concentration of 100 μm peptide. Peptide products of the reaction were separated by HPLC and their Mrs were analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS. Hex, Hexose.

Subcellular Localization of HGT

To determine the protein localization of HGT in Arabidopsis cells, we first prepared P10, P100, and S100 fractions from T87 cells and measured their HGT activities. HGT activity was detected only in the P10 fraction (Fig. 6A), consistent with the presence of HGT in the P10 cell fraction. We next analyzed marker proteins by immunoblotting with specific antibodies that recognize TLG2a or JIM84 (for the Golgi apparatus), Bip or Sec61 (ER membrane), or PIP1 (plasma membrane). Bip, Sec61, and PIP1 were mainly detected in the P10 fraction, suggesting that HGT is localized to the ER and/or plasma membrane. To address the localization of HGT more precisely, we performed a Suc density gradient centrifugation experiment. Total subcellular fractions were extracted from T87 cells in buffers containing either Mg2+ or EDTA. The Mg2+ cation is required for ribosome binding to ER membrane and forming the rough ER. The extracts were separated by Suc density gradient centrifugation in the presence or absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 6, B and C). The presence of HGT in these fractions was determined by measuring HGT activity and the distribution of marker proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting. In the absence of Mg2+, HGT activity could be detected in fractions eight to 13. This pattern of migration was similar to what was observed for Sec61 and Bip, markers for the ER membrane (Fig. 6B). In the presence of Mg2+, HGT-containing fractions were detected in fractions five to 12. Under the same conditions, the other subcellular markers that were tested, TLG2a, JIM84, and PIP1, did not comigrate with HGT activity in either the presence or absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 6, B and C). Taken together, the results indicate that like the ER markers Bip and Sec61, HGT is predominantly localized to the ER membrane.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated the HGT activity involved in the biosynthesis of arabinogalactan, using chemically synthesized peptides as acceptors and UDP-d-Gal as a sugar donor, together with manganese divalent cations as a cofactor. Although Lang previously measured β-galactosyltransferase activity of a green alga via detection of incorporation of [14C]-Gal from UDP-[14C]-Gal in glycoproteins (Lang, 1982), the method has the significant disadvantage in that it detects not only HGT activity but also elongation of arabinogalactans. By contrast, the method described here distinguishes HGT activity from other galactosylation activities.

Protein O-mannosyltransferase 1 (Pmt1p) from yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (POFUT1) from human have been identified as ER-localized protein O-glycosyltransferases (Willer et al., 2003; Luo and Haltiwanger, 2005). However, the membrane topology and enzymatic properties of Pmt1p and POFUT1 are different. Pmt1p is a seven-transmembrane protein and requires a divalent magnesium cation for activity (Strahl-Bolsinger and Scheinost, 1999). In contrast, POFUT1 is retained in the ER via the presence of a KDEL-like sequence at its C terminus, and requires a divalent manganese cation for activity (Luo and Haltiwanger, 2005). A manganese divalent cation is also required for most type II membrane-bound protein O-glycosyltransferases. Because the characteristics of HGT are more similar to those of POFUT1, it is plausible that HGT could be a type II membrane protein rather than an integral transmembrane protein. However, this speculation requires further experimental evidences to prove it.

The Dictyostelium GnT51 gene encodes a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine: Hyp polypeptide N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (Van Der Wel et al., 2002). This enzyme is the only reported example of a glycosyltransferase that can transfer a sugar residue to the Hyp of a polypeptide. BLAST analysis fails to identify any Arabidopsis proteins with significant similarity to the protein encoded by GnT51, suggesting that the Arabidopsis HGT protein is unrelated at the primary sequence level.

The results of subcellular separation revealed that HGT is mainly localized to the ER. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase (P4H) is reportedly a resident protein in the lumen of the ER in vertebrate and mammalian cells (Kivirikko et al., 1989; Walmsley et al., 1999; Ko and Kay, 2001), whereas P4H is detectable not only in the ER but also in the Golgi apparatus in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells (Yuasa et al., 2005). Because the Gal transfer reaction occurs after Pro hydroxylation by P4H, HGT must be located further downstream of the protein transport pathway than P4H. Because TLG2a and JIM84 antibodies are trans-Golgi and not cis-Golgi markers, it remains possible that the HGT is localized not only in the ER but also in the cis-Golgi. Therefore, further analysis will be necessary to determine the precise subcellular distribution of HGT.

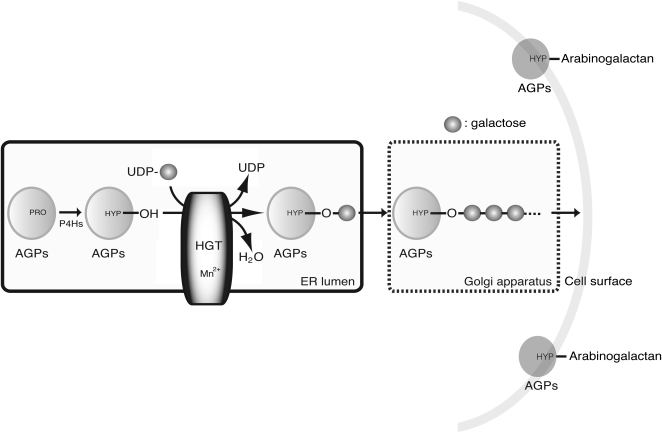

When a microsomal fraction was used as an enzyme source, galactosylation occurred on up to five residues. In contrast, when the P10 fraction was used as an enzyme source, only one Gal residue was transferred to a synthetic peptide, suggesting that the elongation activity of arabinogalactans is localized to an organelle other than the ER, probably the Golgi apparatus. A hypothetical model of arabinogalactan synthetic pathway in plant cells is shown in Figure 7. The proteins are first modified by hydroxylation of Pro. Next, HGT transfers a Gal residue to a Hyp using UDP-d-Gal as a donor. This activity requires a divalent manganese cation. Finally, galactosylated AGPs are transported to the Golgi apparatus, where the elongation reactions occur, and, finally, the proteins localize to the cell surface. The identification of genes involved in HGT reactions and the following arabinogalactan synthesis should help improve our understanding of these important protein modification steps.

Figure 7.

Schematic of the HGT reaction. PRO, Pro residue of AGPs; HYP, Hyp residue of AGPs; Mn2+, divalent cation of manganese. Arrows indicate the protein transport pathway in Arabidopsis cells.

The results of substrate specificity analysis revealed that HGT can transfer a Gal residue to the Hyp residue of the unique polypeptide involving the minimal sequence of A-(O/P/A)-A-O-A (Fig. 5). This is partly consistent with the previous indication on the consensus sequence of X-O-X-O- repeats of AGPs for Hyp O-galactosylation (Tan et al., 2003). However, it remains unclear if the above sequence containing the A at the second amino acids instead of O or P (-A-A-A-O-A-) may have enough activity as compared with those containing (-A-O-A-O-A-) or (-A-P-A-O-A-), because the observed MS intensity for the O-galactosylated product is weaker for AtAGP14-5 peptide than those for the other substrate peptides, while the MS intensity does not correctly reflect the amount of the observed peak. Therefore, further experiments are necessary to confirm if the alternating Hyp (O) residues are essential for the recognition by HGT.

The preferable substrates seemed to be the peptides containing at least two alternate imino acid residues, at least one of which is a Hyp residue. This nature fits to the previously described hypothesis that the repeated noncontiguous Hyps, which take poly-Pro II structure (van Holst and Fincher, 1984), are the site for the attachment of arabinogalactan (Kieliszewski, 2001). However, HGT could transfer Gal residue to not only peptides containing two alternate imino acids but also a peptide with only a single Hyp residue with no other imino acids (AtAGP14-4). This observation is consistent with the in vivo characterization of arabinogalactosylation motif (Shimizu et al., 2005) as the surrounding sequence of Hyp residue in AtAGP14-4 clearly matches with the motif reported in the article.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

These results indicate that a Gal residue could be attached to a unique Hyp residue of a recombinant protein, for example, human antibody, when expressed in plants. There is a possibility that the extraneous glycosylation becomes an antigen for human. Although several studies have been made on remodeling of N-glycosylation in various hosts for expression of recombinant glycosylated proteins, little is made on remodeling by O-glycosylation (Chiba and Jigami, 2007). In the future, it will be important to develop strategies for remodeling and repression of heterologous O-glycosylation in plants. We expect that the in vitro assay method described here will be useful to screen for specific inhibitors of HGT activity.

Recently, several unique glycosyltransferases were characterized using a cell extract approach, and the genes encoding these activities were subsequently identified in plants (Akita et al., 2002; Konishi et al., 2006; Sterling et al., 2006; Qu et al., 2008). Our success in detecting HGT activity in the ER-enriched fraction of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and the assay method developed in this study open the way to identification of the corresponding genes.

Plant Material

Suspension-cultured Arabidopsis T87 cells were grown on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 3% Suc and cultured for 2 weeks. The flasks were shaken at 120 rpm at 25°C.

Preparation of Microsomal Fractions

T87 cells were harvested on filter paper and lysed using a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. The lysed cells were suspended in buffer A, 100 mm MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0), 1 mm MnCl2 with the EDTA-free protease inhibitor (one tablet of Complete per 50 mL; Roche Diagnostics GmbH). The suspension was centrifuged at 3,000g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The resultant supernatants were centrifuged at 160,000g for 60 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in buffer A to generate a microsomal fraction. The fraction was dialyzed in 10 mm ammonium-acetate buffer (pH 7.0) overnight at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined according to the manufacturer's protocol using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

Preparation of P10, P100, and S100 Enzyme Fractions

Cells lysed as described above were suspended in buffer A. The suspension was centrifuged at 3,000g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The resultant supernatants were centrifuged at 14,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The ER-enriched pellets were resuspended in buffer A to generate a P10 fraction. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 160,000g for 60 min at 4°C to generate a Golgi-enriched pellet fraction (P100) and a cytosolic supernatant fraction (S100). Each fraction was dialyzed in 10 mm ammonium-acetate buffer (pH 7.0) overnight at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined according to the manufacturer's protocol using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

Assay for HGT Activity

Assay mixtures contained the following components in a total volume of 50 μL: 1 mm UDP-Gal, 100 μm substrate peptide acceptor, 100 mm MOPS-NaOH buffer, pH 7.0, containing (final concentrations) 0.2% (w/v) Triton X-100, 1 mm MnCl2, and 30 μg of crude enzyme fractions (i.e. P10, P100, or S100 fractions). After the addition of the enzyme preparation, the mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 60 min. The reactions were stopped by heating at 95°C for 3 min. Products (10 μL) were separated by reverse-phase chromatography and detected using a fluorescent detector (model RF-10A XL; Shimadzu). FITC-labeled peptides were purchased from Operon Co., Ltd. or AnyGen, and used as an acceptor substrate. FITC-labeled glycopeptides were detected at a fluorescence intensity of 530 nm (excitation at 488 nm). The FITC-labeled peptides were synthesized using the Fmoc/tBu technique (Coin et al., 2007).

Suc Gradient

T87 cells were grown for 14 to 20 d at 25°C. All manipulations were done on ice or at 4°C. T87 cells (5 g fresh weight) were ground with a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. Lysed cells were suspended at 0.5 mL/g in buffer B containing 50 mm MOPS-NaOH, pH 7.0, 45% (w/v) Suc, EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), and either 5 mm EDTA or 5 mm MgCl2. The suspension was centrifuged at 3,000g for 10 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was loaded onto a 50% Suc solution. A discontinuous gradient was formed by adding 0.5 mL of 55% Suc, 0.5 mL of 50% Suc, and 1.2 mL of 45% Suc (including the cell sample), then adding 0.5 mL of 40%, 35%, 30%, 25%, and 20% Suc solutions sequentially on the surface of the supernatant. The gradient was centrifuged at 100,000g for 18 h and collected in 280-μL increment fractions. Specific membrane fractions were identified by immunoblotting using antibodies against organelle-specific markers.

Immunoblotting and Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting. Anti-PIP1 (Ohshima et al., 2001) and anti-Sec61 (Yuasa et al., 2005) antibodies were described previously. Anti-Bip and JIM84 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology or CarboSource Services, respectively. Anti-AtTLG2a (Bassham and Raikhel, 2000) was kindly provided by Dr. N.V. Raikhel. Each primary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:1,000. We then used anti-rabbit IgG conjugate HRP (Cell Signaling Technology) to detect anti-Sec61, anti-AtTLG2a, and anti-PIP1; anti-rat IgM conjugate HRP to detect JIM84; or anti-goat IgG conjugate HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect anti-Bip. In each case, secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:5,000. An ECL Plus kit (Amersham Biosciences) was used to visualize the immunoreactive proteins. Chemical fluorescent signals on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane were recorded using a LAS-3000 imaging system (FUJIFILM Corporation).

HPLC Analysis

The products were analyzed by HPLC with a reverse-phase column cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (250 × 4.6 mm; Nacalai Tesque). The column was equilibrated with 20% acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The FITC-labeled glycopeptides were eluted using a linear gradient of 20% to 40% acetonitrile over a period of 30 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The FITC-labeled glycopeptides were detected by the fluorescence intensity at 530 nm (excitation, 488 nm).

MS

The enzymatic products were collected and lyophilized and suspended with deionized water. The matrix used was α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma) dissolved at 10 mg/mL in 0.1% TFA:acetonitrile (5:5, v/v). Equal volumes (1 μL each) of the sample and the matrix solution were mixed and dried on the target plate. The fractions were analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS. Mass spectra were obtained on an Ettan MALDI-ToF-MS (GE Healthcare UK Ltd.) in the positive-ion mode.

Monosaccharide Analysis

Monosaccharides from the O-glycosylated peptides were analyzed by the method described previously (Chigira et al., 2008). The HPLC-purified peptide sample was incubated in 4 m TFA at 100°C for 4 h and dried. Next, the hydrolysates were labeled with fluorescent ABEE using an ABEE labeling kit (Seikagaku Corporation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The ABEE-labeled monosaccharides were analyzed by HPLC using a cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (250 × 4.6 mm; Nacalai Tesque) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with 0.1% TFA buffer containing 10% acetonitrile at 45°C. The ABEE-labeled monosaccharides were detected by the UV intensity at 305 nm.

Source of Sugar Nucleotides

UDP-d-Glc, UDP-d-Gal, UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, and UDP-d-GlcUA were purchased from Sigma. UDP-l-arabinopyranose and UDP-d-Xyl were from CarboSource Services. UDP-l-Rha was synthesized using a cytoplasmic fraction from yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells expressing RHM2/MUM4, which encodes UDP-l-Rha synthase, and purified by HPLC using a Develosil RPAQUEOUS column (250 × 4.6 mm, Nomura Chemical Co., Ltd.; Oka et al., 2007). Chemically synthesized UDP-l-Araf was obtained from the Peptide Institute.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers number AF195895 for AtAGP14.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yasunori Chiba and Toshihiko Kitajima of the Research Center for Medical Glycoscience, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, and Dr. Hiroto Hirayama of the Glycometabolome Team, RIKEN Advanced Science Institute, for many helpful discussions. We also thank Yuji Komachi and Yu-ichiro Fukamizu of the Department of Applied Microbial Technology, Faculty of Biotechnology and Life Science, Sojo University, for their kind help with the monosaccharide analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Yoshifumi Jigami (jigami.yoshi@aist.go.jp).

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Akita K, Ishimizu T, Tsukamoto T, Ando T, Hase S (2002) Successive glycosyltransfer activity and enzymatic characterization of pectic polygalacturonate 4-alpha-galacturonosyltransferase solubilized from pollen tubes of Petunia axillaris using pyridylaminated oligogalacturonates as substrates. Plant Physiol 130 374–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber C, Rösti J, Rawat A, Findlay K, Roberts K, Seifert GJ (2006) Distinct properties of the five UDP-D-glucose/UDP-D-galactose 4-epimerase isoforms of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 281 17276–17285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassham DC, Raikhel NV (2000) AtVPS45 complex formation at the trans-Golgi network. Mol Biol Cell 11 2251–2265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Jigami Y (2007) Production of humanized glycoproteins in bacteria and yeasts. Curr Opin Chem Biol 11 670–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigira Y, Oka T, Okajima T, Jigami Y (2008) Engineering of a mammalian O-glycosylation pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: production of O-fucosylated epidermal growth factor domains. Glycobiology 18 303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin I, Beyermann M, Bienert M (2007) Solid-phase peptide synthesis: from standard procedures to the synthesis of difficult sequences. Nat Protoc 2 3247–3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez JM, Kieliszewski MJ, Khitrov N, Somerville C (2006) Characterization of synthetic hydroxyproline-rich proteoglycans with arabinogalactan protein and extensin motifs in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 142 458–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski MJ (2001) The latest hype on Hyp-O-glycosylation codes. Phytochemistry 57 319–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski MJ, Shpak E (2001) Synthetic genes for the elucidation of glycosylation codes for arabinogalactan-proteins and other hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 58 1386–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivirikko KI, Myllyla R, Pihlajaniemi T (1989) Protein hydroxylation: prolyl 4-hydroxylase, an enzyme with four cosubstrates and a multifunctional subunit. FASEB J 3 1609–1617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox JP (2006) Up against the wall: arabinogalactan-protein dynamics at cell surfaces. New Phytol 169 443–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MK, Kay EP (2001) Subcellular localization of procollagen I and prolyl 4-hydroxylase in corneal endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 264 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Ono H, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Kaneko S, Ishii T (2006) Identification of a mung bean arabinofuranosyltransferase that transfers arabinofuranosyl residues onto (1, 5)-linked alpha-L-arabino-oligosaccharides. Plant Physiol 141 1098–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang WC (1982) Glycoprotein biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas. Plant Physiol 69 678–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehle L, Strahl S, Tanner W (2006) Protein glycosylation, conserved from yeast to man: a model organism helps elucidate congenital human diseases. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 45 6802–6818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Haltiwanger RS (2005) O-fucosylation of notch occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 280 11289–11294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Watanabe N, Nakamura K (1995) O-glycosylation of a precursor to a sweet potato vacuolar protein, sporamin, expressed in tobacco cells. Plant J 8 877–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima Y, Iwasaki I, Suga S, Murakami M, Inoue K, Maeshima M (2001) Low aquaporin content and low osmotic water permeability of the plasma and vacuolar membranes of a CAM plant Graptopetalum paraguayense: comparison with radish. Plant Cell Physiol 42 1119–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Nemoto T, Jigami Y (2007) Functional analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana RHM2/MUM4, a multidomain protein involved in UDP-D-glucose to UDP-L-rhamnose conversion. J Biol Chem 282 5389–5403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Egelund J, Gilson PR, Houghton F, Gleeson PA, Schultz CJ, Bacic A (2008) Identification of a novel group of putative Arabidopsis thaliana beta-(1,3)-galactosyltransferases. Plant Mol Biol 68 43–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz CJ, Ferguson KL, Lahnstein J, Bacic A (2004) Post-translational modifications of arabinogalactan-peptides of Arabidopsis thaliana: endoplasmic reticulum and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor signal cleavage sites and hydroxylation of proline. J Biol Chem 279 45503–45511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert GJ, Roberts K (2007) The biology of arabinogalactan proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58 137–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Igasaki T, Yamada M, Yuasa K, Hasegawa J, Kato T, Tsukagoshi H, Nakamura K, Fukuda H, Matsuoka K (2005) Experimental determination of proline hydroxylation and hydroxyproline arabinogalactosylation motifs in secretory proteins. Plant J 42 877–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak E, Leykam JF, Kieliszewski MJ (1999) Synthetic genes for glycoprotein design and the elucidation of hydroxyproline-O-glycosylation codes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 14736–14741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling JD, Atmodjo MA, Inwood SE, Kumar Kolli VS, Quigley HF, Hahn MG, Mohnen D (2006) Functional identification of an Arabidopsis pectin biosynthetic homogalacturonan galacturonosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 5236–5241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl-Bolsinger S, Scheinost A (1999) Transmembrane topology of pmt1p, a member of an evolutionarily conserved family of protein O-mannosyltransferases. J Biol Chem 274 9068–9075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Leykam JF, Kieliszewski MJ (2003) Glycosylation motifs that direct arabinogalactan addition to arabinogalactan-proteins. Plant Physiol 132 1362–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wel H, Morris HR, Panico M, Paxton T, Dell A, Kaplan L, West CM (2002) Molecular cloning and expression of a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc):hydroxyproline polypeptide GlcNAc-transferase that modifies Skp1 in the cytoplasm of dictyostelium. J Biol Chem 277 46328–46337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holst GJ, Fincher GB (1984) Polyproline II confirmation in the protein component of arabinogalactan-protein from Lolium multiflorum. Plant Physiol 75 1163–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley AR, Batten MR, Lad U, Bulleid NJ (1999) Intracellular retention of procollagen within the endoplasmic reticulum is mediated by prolyl 4-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem 274 14884–14892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer T, Valero MC, Tanner W, Cruces J, Strahl S (2003) O-mannosyl glycans: from yeast to novel associations with human disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol 13 621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa K, Toyooka K, Fukuda H, Matsuoka K (2005) Membrane-anchored prolyl hydroxylase with an export signal from the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant J 41 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]