Abstract

Background:

As cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are discovered with advanced imaging techniques, pancreatic surgeons often struggle with identifying who is at risk of having or developing pancreatic cancer. We sought to review our experience with the surgical management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas to determine pre-operative clinical indicators of malignancy or premalignant (i.e. mucinous) lesions.

Methods:

Between 1996 and 2007, 114 consecutive patients with cystic neoplasms of the pancreas underwent a pancreatectomy. Invasive adenocarcinoma was identified in 35 whereas 79 had benign lesions. Mucinous lesions were considered premalignant and consisted of 29 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) and 17 mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN). The remaining 33 benign lesions were serous microcystic adenomas. Descriptive statistics were calculated and multivariate logistic regression was performed. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for continuous variables and the area under the curves compared. Likelihood ratios were calculated from the combinations of predictors.

Results:

Patients with pancreatic cancer arising from a cystic neoplasm were older than those with benign cysts. Mucinous lesions with or without associated cancer were more likely to be symptomatic and present with elevated serum carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 levels. Cancers more commonly presented in the head of the pancreas and were associated with longer hospitalizations after resection. Using multivariate logistic regression, size and elevated CA19-9 were predictors of malignancy whereas male gender and size were predictors of mucinous lesions with or without malignancy. Size, however, was not an accurate test to determine premalignant or malignant lesions using area under the ROC curve analysis whereas CA19-9 performed the best regardless of gender or lesion location.

Conclusions:

Based upon our single institution experience with resection of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, we advocate an aggressive surgical approach to any patient with a cystic neoplasm of the pancreas and associated elevated CA19-9.

Keywords: cystic neoplasms, pancreas, adenocarcinoma, CA19-9, IPMN, MCN

Introduction

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas include serous cystadenomas or serous microcystic adenomas (SMA), mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). First described in the 1990s, mucinous lesions (i.e. MCN, IPMN) represent premalignant neoplasms capable of transforming into invasive adenocarcinoma with subsequent poor prognosis. As cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are more commonly discovered with advanced imaging techniques, pancreatic surgeons are often faced with the daunting task of determining who should or, perhaps more difficult, who should not undergo a pancreatectomy. Radiographical characteristics alone are notoriously inaccurate in predicting malignant potential of cystic pancreatic neoplasms.1 Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and cyst fluid analysis for mucin, cellular atypia and carcinoembryologic antigen (CEA) hold promise in identifying those lesions with malignant potential.2–4 Utilization of EUS is not always feasible, particularly in rural areas where many initial assessments of pancreatic cystic neoplasms are made. Limitations in availability or means of accessing EUS,5,6 mean clinicians must rely on non-invasive techniques of assessing risk of pancreatic cancer.

SMA is the most common pancreatic cystic neoplasm, representing more than 30% of all cystic neoplasms.7,8 Similar to pancreatic cancers, SMAs present in the 5th–7th decade of life. These lesions are typically located in the body and tail of the pancreas but can arise throughout the pancreatic parenchyma and may be confused with cancerous lesions on pre-operative imaging, particularly if there is a solid component.9,10 Although these lesions are often indolent, particularly when small (<4 cm), and carry virtually no risk of malignant transformation, surgery is generally recommended for those patients who are symptomatic or have larger lesions (>4 cm), with an excellent prognosis with regards to mortality and disease-free survival.11,12

In contradistinction from their serous counterparts, mucin-producing cystic neoplasms are considered premalignant and often present after malignant transformation has already occurred.12,13 The two sub-types of MCN and IPMN have distinct characteristics and presentations. While MCNs are almost exclusively found in women, predominantly in the body and tail of the pancreas, IPMNs are more common in men and typically located in the head of the pancreas.14–16 Surgery is recommended for all patients suspected of having MCN who are suitable surgical candidates as pre-operative assessment of associated malignancy is not reliable as well as the potential for future malignant transformation.12 Main duct IPMNs are similarly recommended to undergo surgical resection for risk of occult or future malignancy.17

As an institution that, until recently, did not have ready access to EUS, most treatment decisions regarding resection for cystic neoplasms of the pancreas were based upon non-invasive clinical characteristics. It is for this reason that we sought to review our experience with the surgical management of these cystic lesions to determine pre-operative indicators of malignancy or premalignant (i.e. mucinous) lesions.

Methods

After approval by the Institutional Review Board at the Ohio State University, the charts of 114 consecutive patients who presented to our institution with cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and subsequently underwent pancreatectomy between 1996 and 2007 were reviewed. Our criteria for resection were generally based on location of tumour, size, tumour markers and the presence of symptoms. Clinicopathological characteristics such as age, gender, clinical presentation, tumour markers, location of tumour and size of tumour were reviewed and compared using anova or Student's t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for categorical data. First, benign lesions (SMA and premalignant mucinous tumours) were compared with those lesions harbouring malignancy and the descriptive statistics of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for each variable or combinations of variables. A multivariate logistic regression was then performed to identify predictors associated with malignancy. Next, SMAs were compared with mucinous lesions with and without associated malignancy and descriptive statistics were tabulated. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was again undertaken to identify predictors of premalignancy and malignancy. In other words, an attempt was made to identify predictors of the need for surgical resection. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created, and the area under the ROC curves was calculated for the continuous variable of age, pre-operative carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 and lesion size. Likelihood ratios (both positive and negative) were calculated for the same dataset to determine the post-resection probability of premalignancy and malignancy based on the predictors in question. Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS vs. 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Out of the 114 patients who underwent pancreatectomy for cystic lesions, invasive adenocarcinoma was identified in 35, whereas 79 had benign (i.e. adenoma or borderline) lesions. The 46 mucinous lesions were considered premalignant and consisted of 29 IPMNs and 17 MCNs. The remaining 33 benign lesions were SMAs. Malignant lesions tended to be diagnosed in older patients, whereas SMAs were more common in women (Table 1). SMAs were less likely to present with symptoms. Pain was the most common presenting complaint in benign lesions, whereas obstructive jaundice was associated more commonly with malignant lesions. CA19-9 was rarely elevated in serous lesions but was six times more likely to be elevated in association with mucinous lesions and nearly 10 times more likely to be elevated when a malignancy was present. Cystic neoplasms associated with malignancy were more commonly located in the head of the pancreas, whereas they were more likely to be in the body or tail of the pancreas in benign lesions. Finally, the median size of all resected lesions was 4 cm and significantly different in serous, mucinous or malignant neoplasms.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of all patients undergoing a pancreatectomy for cystic lesions of the pancreas based upon final tumour type

| All | Serous | Mucinous | Malignant | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 114 | 33 | 46 | 35 | |

| Median age (range) | 62 (24–84) | 59 (38–83) | 59 (24–83) | 68 (36–84) | 0.07 |

| Female | 74 (65%) | 26 (78%) | 28 (61%) | 20 (57%) | 0.13 |

| Symptoms | 90 (79%) | 19 (5%) | 40 (87%) | 31 (89%) | <0.01 |

| Elevated CA19-9a | 23 (37%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (36%) | 14 (56%) | <0.01 |

| Head of pancreas | 49 (43%) | 8 (24%) | 15 (33%) | 26 (74%) | <0.01 |

| Median size (range) | 4 cm (0.6–18.5) | 3.5 cm (1.0–8.0) | 3.6 cm (0.6–15.0) | 4.5 cm (2.0–18.5) | 0.11 |

| Median length of stay (d) | 9 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 0.03 |

| Complications | |||||

| Total | 62 | 12 | 28 | 22 | |

| Patients | 46 (40%) | 9 (27%) | 21 (46% | 16 (46%) | 0.29 |

| Mortality | 7 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 0.63 |

CA19-9 data available for 62 patients (16 serous, 22 mucinous, 25 malignant).

The median hospitalization was 9 days for all patients; it was longest in those who had an associated malignancy and shortest in those with serous neoplasms (Table 1). Commensurate with length of stay, complications were less common after a pancreatectomy for serous lesions, although not statistically significant. A pancreatic fistula, defined as amylase-rich drain output of any volume on or after post-operative day three in accordance with the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula,18 was the most common complication, occurring in nine (8%) patients overall. Haemorrhage occurred in eight patients (7%) and delayed gastric emptying occurred in five patients (4%). Other complications included: abscess 8, wound infection 6, pulmonary embolism 6, pneumonia 4, urinary tract infection 4, bowel obstruction 3, bacteraemia 2, bowel perforation 2, pneumothorax 1, parotiditis 1, acute renal failure 1 and incisional hernia 1. No significant differences were seen in complications based upon final lesion histology. Seven patients (6%) died in the peri-operative period with the highest mortality in patients with concomitant malignancy (Table 1).

Benign vs. malignant cystic neoplasms

Descriptive statistics were calculated for several variables and are shown in Table 2. The presence of symptoms was the most sensitive variable for the presence of malignancy and had the greatest negative predictive value. However, the presence of symptoms alone was not predictive of malignancy given the low specificity and positive predictive value. As a single variable, elevated CA19-9 was most specific for malignancy but was less sensitive than the presence of symptoms or location of the lesion. Elevated CA19-9 had the highest positive likelihood ratio. In other words, when CA19-9 levels measured greater than 35 U/ml there was a three-fold greater chance that the lesion was malignant as compared with benign lesions. Combining symptoms with elevated CA19-9 had the highest specificity (84%) and sensitivity (64%). The overall positive likelihood ratio for these combined variables is four, which suggests these pre-operative markers, when present, increase the likelihood of malignancy four times relative to benign lesions. Other combinations of clinical findings did not result in meaningful improvements in sensitivity or specificity for malignancy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for predictors of malignancy

| Variable | Benign (n= 79) | Malignant (n= 35) | P-value | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) | 59.1 (13.2) | 65 (12.4) | 0.02 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Female | 68% | 57% | 0.29 | 57% | 32% | 27% | 63% | 0.83 | 1.34 |

| Symptoms | 83% | 94.3% | 0.14 | 94% | 25% | 36% | 91% | 1.25 | 0.24 |

| High CA19-9 (>35 mg/dl) | 22% | 67% | 0.001 | 67% | 78% | 64% | 80% | 3.04 | 0.42 |

| Head of the pancreas | 29% | 71% | 0.001 | 71% | 71% | 52% | 85% | 2.45 | 0.41 |

| Size cm Mean (SD) | 4.1 (2.9) | 5.6 (3.6) | 0.04 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Symptoms & high CA19-9 | 64% | 84% | 0.0082 | 64% | 84% | 82% | 61% | 4 | 0.43 |

| Symptoms & head of pancreas | 56.9% | 83% | 0.03 | 57% | 83% | 49% | 62% | 3.35 | 0.52 |

| High CA19-9 & head of pancreas | 28% | 70% | <0.001 | 28% | 70% | 45% | 83% | 4.2 | 1.03 |

LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Next, we utilized multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of malignancy (Table 3). Increasing age, elevated CA19-9, location within the head of pancreas and the presence of symptoms were significant in the univariate analysis. However, when entered into the multivariate model, only elevated CA19-9 and increasing size were predictive of harbouring a focus of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of pre-operative clinical predictors of malignancy

| Variable | UnivariateP-value | MultivariateP-value |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 0.25 | N.S. |

| Age | 0.03 | N.S. |

| Location (head vs. body/tail) | <0.001 | N.S. |

| Elevated CA19-9 (>35 mg/dl) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Size | 0.19 | 0.025 |

| Symptoms (present vs. absent) | <0.001 | N.S. |

| High CA19-9 & Head of Pancreas | 0.143 | N.S. |

Benign vs. premalignant or malignant cystic lesions

In order to identify predictors of premalignant or malignant cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (i.e. those with clear indication for resection), logistic regression analysis was undertaken in addition to calculating positive and negative likelihood ratios (Table 4). Male gender, increasing age, elevated CA19-9 and location of the lesion within the head of the pancreas were all associated with (pre)malignant histology. However, only male gender and increasing size were predictive on multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of pre-operative clinical predictors of mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas with and without associated malignancy

| Variable | UnivariateP-value | MultivariateP-value |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age | <0.001 | N.S. |

| High CA19-9 | 0.018 | N.S. |

| Location (head vs. body/tail) | <0.001 | N.S. |

| Size | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms (present vs. absent) | 0.2 | N.S. |

CA19-9 as a predictor of malignancy and premalignancy

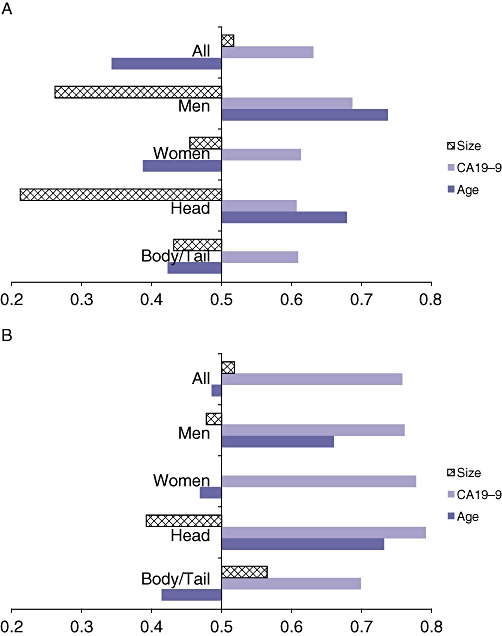

We next sought to determine which of the continuous variables of age, lesion size and CA19-9 would be the most accurate measurement in determining the need for resection (i.e. mucinous with and without malignancy). ROC curves were calculated for each of the continuous variables using the dichotomous dependent variable of serous vs. mucinous without associated cancer and serous vs. mucinous with associated cancer (data not shown). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated for each variable and plotted in Fig. 1. An area of 0.5 is considered an inaccurate test whereas an area of 1.0 is considered a perfect test.19,20 For premalignant lesions (i.e. IPMN or MCN without associated cancer), size was never a worthwhile test when considering all patients together or stratifying for gender or lesion location (Fig. 1a). Similarly, age was not a helpful test unless patients were men or had lesions located in the head of the pancreas (AUC = 0.737 and 0.679, respectively). CA19-9, however, can be considered a fair test for all patients regardless of gender or tumour location. When considering all patients with cystic lesions that might be considered surgical candidates (i.e. those with premalignant mucinous lesions or with cystic lesions harboring malignancy), size was never accurate (Fig. 1b). Age was only helpful in men (AUC 0.660) or for lesions located in the head of the pancreas (AUC 0.732). CA19-9, however, was the best test with AUC > 0.7 for all patients regardless of gender or lesion location.

Figure 1.

Plot of area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for continuous variables of size, carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 and age to determine accuracy of each variable for predicting (a) benign mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas and (b) benign or malignant mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas. A value of 0.5 or less is consistent with a meaningless test

Discussion

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are more frequently detected as a result of improved resolution and quality of abdominal imaging combined with a decreased threshold for obtaining these scans. Many cystic lesions are malignant or have malignant potential.21,22 Determining which lesions require resection because of the risk of developing or already harbouring malignancy is often perplexing for the pancreatic surgeon, particularly for high risk or otherwise asymptomatic patients. Despite the combination of advanced imaging techniques and the utility of cyst fluid aspiration, it often still remains a diagnostic dilemma for the surgeon as to which cystic lesions of the pancreas require exptirpation.2,4 The role of EUS and FNA is becoming clear as a valuable tool for predicting lesions at risk.23,24 Unfortunately, EUS is not universally available or feasible for all patients. We retrospectively reviewed our experience with the surgical management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas in order to identify predictors of malignancy or premalignancy using universal clinical variables. Current literature on cystic neoplasms of the pancreas varies from a close surveillance approach in patients with asymptomatic, smaller lesions with no suspicious features on imaging or FNA to a more aggressive surgical approach, especially in patients with size > 3 cm.25,26

Our patients were divided into those with clearly benign lesions without malignant potential (i.e. serous microcystic adenomas or serous cystadenomas), those with premalignant lesions (i.e. IPMN and MCN) and those with cystic lesions associated with invasive ductal adenocarcinoma. As expected, patients with benign lesions tended to be younger than those harbouring malignancy with a female preponderance in those with SMAs. Serous lesions were significantly more likely to be found incidentally, although abdominal pain was still a common presentation. Elevations in CA19-9 were rare in serous lesions whereas more than half of the patients with malignancy demonstrated elevated CA19-9 levels. Mucinous premalignant lesions were uncommonly found to have elevated CA19-9 levels but were significantly more likely than SMAs. Only one SMA presented with an elevated CA19-9 level. Malignant tumors were significantly more likely to present with lesions in the head of the pancreas than benign lesions. However, this may reflect a selection bias as those who presented with associated body or tail malignancies may have been less likely to be selected for resection as a result of advanced disease. Still, others have described the propensity for worrisome cystic lesions to present in the head of the pancreas, and have advocated a more aggressive approach to such lesions.27 Lesion size was not significantly different between lesion types, although there was a trend towards larger tumors harbouring malignancy. Finally, lesion type did not significantly impact complication or mortality rates although malignant lesions were associated with longer hospital stays, perhaps as a result of three-quarters of the patients having lesions located in the head of the pancreas and, thus, requiring a pancreaticoduodenectomy.

To determine predictors of malignancy, we first chose to determine the sensitivity and specificity of gender, symptomatology, elevated CA19-9 and tumor location as these are commonly assessed at initial consultation. Although the sensitivity of symptoms as a variable for capturing malignant tumours was 94%, specificity was quite low as was its PPV. This low PPV is of no concern as once a patient presents with symptoms, they are likely to be offered resection regardless of the risk of malignancy. However, the absence of symptoms is a very important factor in that 91% of patients with asymptomatic lesions did not harbour malignancy. Normal CA19-9 levels and location in the body or tail of the pancreas are also helpful determinants as they increase the likelihood of finding a benign lesion. Combining these variables did little to improve their descriptive characteristics.

Beyond descriptive characteristics associated with malignancy, we utilized logistic regression to identify predictors of malignancy using both univariate and multivariate analysis. Although several variables studied show a favourable trend in predicting malignancy using univariate analysis, only elevated CA19-9 and increasing tumour size were statistically significant using multivariate analysis. Still, given our interest in determining indicators for resection, not merely malignancy alone, to assist in the decision-making process at the time of initial consultation, we grouped premalignant and malignant lesions together to identify clinical predictors. Multivariate logistic regression analysis in this group identified male gender and increasing lesion size as significant predictors.

Lesion size has been suggested to be an invaluable determinant of the risk of (pre)malignancy with most consensus suggesting 3 cm as the cut-off for resection of asymptomatic lesions.28,29 Indeed, using ROC curve analysis, we found 3 cm to be the size at which we were able to obtain the highest sensitivity and specificity (data not shown). Worrisome is that three cancers and 18 premalignant mucinous lesions under 3 cm in size were found in our data set. None of the cancers and only three of the mucinous lesions, however, were asymptomatic. Therefore, it could certainly be argued that, with surveillance, no occult cancers would be missed with a threshold of 3 cm. A recent large multi-institutional study concluded that malignancy in cystic neoplasms 3 cm in size or less was associated with older age, male gender, presence of symptoms and concerning radiographical features.30 Among the asymptomatic patients without concerning radiographical features who underwent resection, the incidence of occult malignancy was 3.3%. However, in our series 20 serous lesions were greater than 3 cm in size; half of which were asymptomatic. Arguably, these patients could have been spared the morbidity of a pancreatectomy with more accurate pre-operative testing.

We attempted to identify which non-invasive clinical characteristic would be most accurate at determining malignancy and/or premalignancy. The area under the ROC curves and likelihood ratios were utilized to determine the general accuracy of the continuous variables of age, CA19-9 and lesion size. Interestingly, size failed to accurately predict malignancy or premalignancy regardless of gender or lesion location. Conversely, CA19-9 proved to be at least a reasonable test at predicting premalignancy and a good test at accurately predicting mucinous lesions with or without malignancy. Thus, CA19-9 was the most helpful test in determining who would potentially benefit from a pancreatectomy, especially when combined with presentation of symptoms or location of the tumour in the head of the pancreas. Age, while not universally accurate, proved to be helpful in identifying men with premalignant lesions and patients with malignant/ premalignant lesions in the head of the pancreas.

It is important to recognize that only the patients selected for resection are included in this study. In general, patients were selected for resection based upon the presence of symptoms, the size (or change in size) of the lesion, or worrisome appearance of the lesion on radiographical imaging. It is certainly possible that the rationale for resection was subjective based upon surgeon experience or other factors that were unable to be ascertained in this retrospective review. What is not known from our data set is the prevalence of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. In other words, we are unable to make definitive conclusions about the aforementioned tests relative to the entire cohort of patients including those who were not selected for resection or, more likely, were never sent for surgical opinion. While in itself this is an obvious weakness of this study, we believe that this patient population represents the typical patient that pancreatic surgeons commonly see and consider for surgical intervention. As such, the data herein may be helpful when counselling patients where the benefit of resection is unclear.

In conclusion, although our data suggest that premalignant and malignant cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are associated with larger lesions, size alone is not an accurate means for determining need for a pancreatectomy. Instead, we suggest that CA19-9 is the most universally accurate non-invasive test to determine who is at risk of having a premalignant or malignant cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. We recommend that patients with incidentally found cystic lesions and an elevated serum CA19-9 be considered for surgical resection, regardless of lesion size.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Fisher WE, Hodges SE, Yagnik V, Moron FE, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Accuracy of CT in predicting malignant potential of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:483–490. doi: 10.1080/13651820802291225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maire F, Voitot H, Aubert A, Palazzo L, O'Toole D, Couvelard A, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: performance of pancreatic fluid analysis for positive diagnosis and the prediction of malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2871–2877. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Guolo P, Polverosi R, Liessi G, Pedrazzoli S. Serum tumor markers and cyst fluid analysis are useful for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic tumors. Cancer. 1996;78:237–243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<237::AID-CNCR8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG. Practice patterns and attitudes toward the role of endoscopic ultrasound in staging of gastrointestinal malignancies: a survey of physicians and surgeons. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2662–2668. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalaitzakis E, Panos M, Sadik R, Aabakken L, Koumi A, Meenan J. Clinicians' attitudes towards endoscopic ultrasound: a survey of four European countries. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:100–107. doi: 10.1080/00365520802495545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compagno J, Oertel JE. Microcystic adenomas of the pancreas (glycogen-rich cystadenomas): a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morohoshi T, Held G, Kloppel G. Exocrine pancreatic tumours and their histological classification. A study based on 167 autopsy and 97 surgical cases. Histopathology. 1983;7:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colonna J, Plaza JA, Frankel WL, Yearsley M, Bloomston M, Marsh WL. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: clinical and pathological features in 33 patients. Pancreatology. 2008;8:135–141. doi: 10.1159/000123606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern JR, Frankel WL, Ellison EC, Bloomston M. Solid serous microcystic adenoma of the pancreas. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassi C, Salvia R, Molinari E, Biasutti C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World J Surg. 2003;27:319–323. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz MH, Mortenson MM, Wang H, Hwang R, Tamm EP, Staerkel G. Diagnosis and management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: an evidence-based approach. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compagno J, Oertel JE. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with overt and latent malignancy (cystadenocarcinoma and cystadenoma). A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:573–580. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Chow PK, Cheow PC, Wong WK, et al. A review of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas defined by ovarian-type stroma: clinicopathological features of 344 patients. World J Surg. 2006;30:2236–2245. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Ohge H, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Suedo T. Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas differentiated by ovarian-type stroma. Surgery. 2006;140:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson LD, Becker RC, Przygodzki RM, Adair CF, Heffess CS. Mucinous cystic neoplasm (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low-grade malignant potential) of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic study of 130 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1–16. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturni G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obuchowski NA. Receiver operating characteristic curves and their use in radiology. Radiology. 2003;229:3–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291010898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgerald TL, Smith AJ, Ryan M, Atri M, Wright FC, Law CH, et al. Surgical treatment of incidentally identified pancreatic masses. Can J Surg. 2003;46:413–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan M, Latona C, Aranha G, Pickleman J. The increasing problem of unusual pancreatic tumors. Arch Surg. 2000;135:644–648. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.6.644. discussion 648–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brugge WR. The role of EUS in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(6) Suppl.:S18–S22. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.110720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linder JD, Geenen JE, Catalano MF. Cyst fluid analysis obtained by EUS-guided FNA in the evaluation of discrete cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a prospective single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goh BK, Tan YM, Thng CH, Cheow PC, Chung YF, Chow PK, et al. How useful are clinical, biochemical, and cross-sectional imaging features in predicting potentially malignant or malignant cystic lesions of the pancreas? Results from a single institution experience with 220 surgically treated patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcea G, Ong SL, Rajesh A, Neal CP, Pollard CA, Berry DP, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: a diagnostic and management dilemma. Pancreatology. 2008;8:236–251. doi: 10.1159/000134279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon WJ, Lee JK, Lee KH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. Cystic neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas: an update of a nationwide survey in Korea. Pancreas. 2008;37:254–258. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181676ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto T, Aramaki M, Yada K, Hirano S, Himeno Y, Shibata K, et al. Optimal management of the branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:261–265. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugiyama M, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atom Y. Predictive factors for malignancy in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1244–1249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CJ, Scheiman J, Anderson MA, Hines OJ, Reber HA, Farrell J, et al. Risk of malignancy in resected cystic tumors of the pancreas < or = 3 cm in size: is it safe to observe asymptomatic patients? A multi-institutional report. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:234–242. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]