Abstract

Objective

To characterize distinct and clinically meaningful subtypes of disability, defined on the basis of the number and duration of disability episodes, and to determine whether the incidence of these disability subtypes differ according to age, sex, and physical frailty.

Design, Setting and Participants

Prospective cohort study of 754 community-living residents of greater New Haven, Connecticut, who were 70 years or older and initially nondisabled in four essential activities of daily living.

Measurements

Disability was assessed during monthly telephone interviews for nearly eight years, while physical frailty was assessed during comprehensive home-based assessments at 18-month intervals. The incidence of five disability subtypes was determined within the context of the 18-month intervals among participants who were nondisabled at the start of the interval: transient, short-term, long-term, recurrent, and unstable.

Results

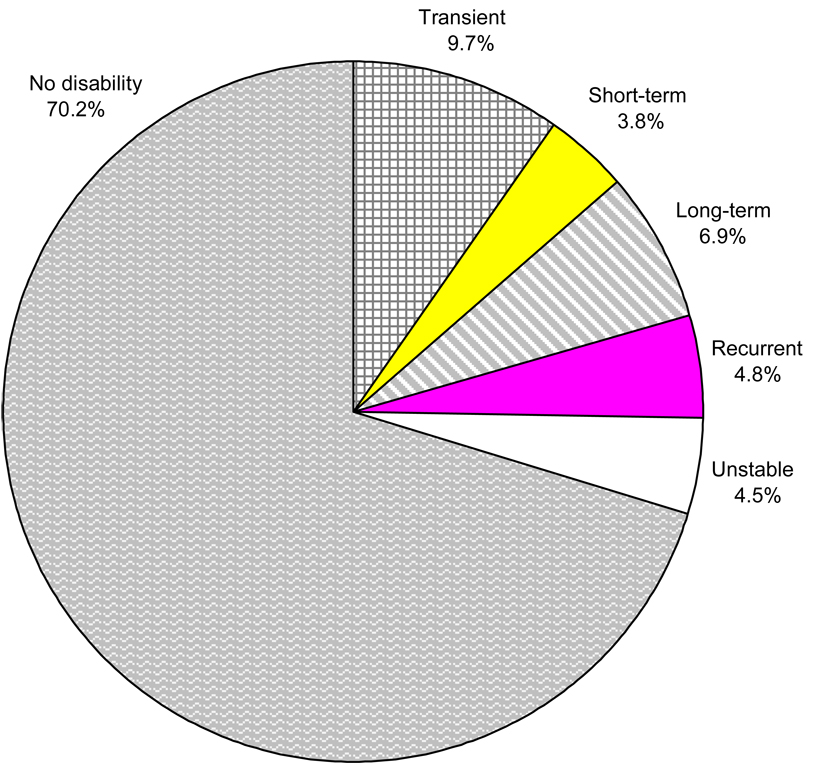

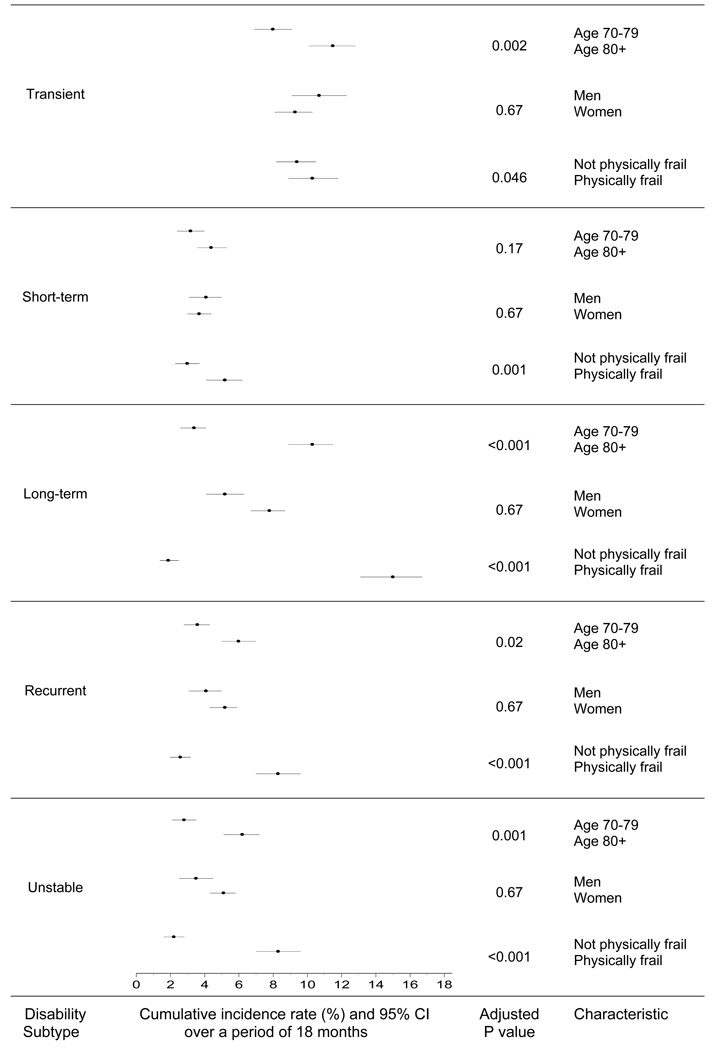

Incident disability was observed in 29.8% of the 18-month intervals. The most common subtypes were transient disability (9.7% of all intervals), defined as a single disability episode lasting only one month, and long-term disability (6.9%), defined as one or more disability episodes, with at least one lasting six or more months. About a quarter (24.7%) of all participants had two or more intervals with an incident disability subtype. While there were no gender differences in the incidence rates for any of the subtypes, differences in rates were observed for each subtype according to age and physical frailty, with only one exception, and were especially large for long-term disability.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the mechanisms underlying the different disability subtypes may differ. Additional research is warranted to evaluate the natural history, risk factors, and prognosis of the five disability subtypes.

Keywords: aged, cohort studies, disability evaluation, activities of daily living

INTRODUCTION

During the past decade, evidence supporting the dynamic nature of disability has emerged with the availability of multiple waves of data from longitudinal studies, such as the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (1,2), the Longitudinal Study on Aging (3), and the National Long-Term Care Survey (4). As noted by Guralnik and Ferrucci (5), these and other studies have documented transitions in disability that have followed nearly every conceivable pattern. Nonetheless, the ability of these studies to precisely characterize the course of disability over time has been somewhat limited by the relatively long intervals, ranging from 6 months to 6 years, between the assessments of disability (6–16).

Informed by an ongoing longitudinal study that includes monthly assessments of functional status over the course of nearly eight years, we have recently shown that disability is reversible and often recurrent (17,18). Moreover, we have found that multiple transitions between different disability states are common among older persons, particularly those who are physically frail, and that the range in number of these transitions is very large (19). These findings support an emerging paradigm of disability as a complex and highly dynamic process with considerable heterogeneity, and they highlight the need for additional research to further enhance our understanding of the disabling process among older persons. The objectives of the current study were twofold: first, to characterize distinct and clinically meaningful subtypes of disability; and second, to determine whether the incidence of these disability subtypes differ according to age, sex, and physical frailty, a state of increased vulnerability to an array of adverse outcomes (20).

METHODS

Study Population

Participants were members of the Precipitating Events Project, a longitudinal study of 754 community-living persons, aged 70 years or older, who were initially nondisabled (i.e. required no personal assistance) in four essential activities of daily living—bathing, dressing, walking inside the house, and transferring from a chair (21). Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive impairment with no available proxy (22), inability to speak English, diagnosis of a terminal illness with a life expectancy less than 12 months, and a plan to move out of the New Haven area during the next 12 months.

The assembly of the cohort, which took place between March 1998 and October 1999, has been described in detail elsewhere (18,21). Potential participants were identified from a computerized list of 3,157 age-eligible members of a large health plan in greater New Haven, Connecticut. To minimize potential selection effects, each member was assigned a unique number using a computerized randomization program, and screening for eligibility and enrollment proceeded sequentially. Eligibility was determined during a screening telephone interview and was confirmed during an in-home assessment. Persons who were physically frail, as denoted by a timed score of greater than 10 seconds on the rapid gait test (i.e. walk back and forth over a 10-ft [3-m] course as quickly as possible), were oversampled to ensure a sufficient number of participants at increased risk for disability (9,23), as described in detail elsewhere (21). In brief, after the prespecified number of nonfrail participants were enrolled, potential participants were excluded if they had a low likelihood of physical frailty based on the telephone screen and, subsequently, if they were found not to be physically frail during the in-home assessment. In the absence of a gold standard, operationalizing physical frailty as slow gait speed is justified by its high face validity (24), clinical feasibility (25,26), and strong epidemiologic link to functional decline and disability (9,27,28). Only 4.6% of the 2,753 health plan members who were alive and could be contacted refused to complete the screening telephone interview, and 75.2% of the eligible members agreed to participate in the project. Persons who refused to participate did not differ significantly from those who were enrolled in terms of age or sex. The study protocol was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and all participants provided verbal informed consent.

Data Collection

Comprehensive home-based assessments were completed at baseline and subsequently at 18-month intervals for 90 months, while telephone interviews were completed monthly for up to 90 months. Deaths were ascertained by review of the local obituaries and/or from an informant during a subsequent telephone interview. Two hundred eighty six (37.9%) participants died after a median follow-up of 50 months, while 36 (4.8%) dropped out of the study after a median follow-up of 22 months. Data were otherwise available for 99.4% of the 56,266 monthly telephone interviews, with little difference between the decedents (98.9%) and nondecedents (99.6%).

During the comprehensive assessments, data were collected on demographic characteristics, physical frailty as previously described, cognitive status as assessed by the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (29), and nine self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions: hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hip fracture, chronic lung disease, and cancer. Participants were considered to be cognitively impaired if they scored less than 24 on the MMSE (29).

Assessment of Disability

Complete details regarding the assessment of disability, including formal tests of reliability and accuracy, are provided elsewhere (18,22). During the monthly telephone interviews and each of the comprehensive assessments, participants were evaluated for disability using standard questions that were identical to those used during the screening telephone interview (22). For each of the four essential activities of daily living (bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring), we asked, “At the present time, do you need help from another person to (complete the task)?” Participants who needed help with any of the tasks were considered to be disabled. Operationalizing disability as the need for personal assistance, as opposed to difficulty, denotes a more severe form of disability (30). Participants were not asked about eating, toileting, or grooming during the monthly interviews. The incidence of disability in these three activities of daily living is low among nondisabled, community-living older persons (9,23). Furthermore, it is highly uncommon for disability to develop in these activities of daily living without concurrent disability in bathing, dressing, walking, or transferring (9,23,31). Among a subgroup of 91 participants who were interviewed twice within a 2-day period by different interviewers, we found that the reliability of our disability assessment was substantial (32), with Kappa = 0.75 for disability (present/absent) in one or more of the four activities of daily living. Kappa was 1.0 for the 18 paired interviews that were completed independently by different interviewers on the same day. For participants with significant cognitive impairment, which was reassessed every 18 months, the monthly interviews were completed with a designated proxy. The accuracy of these proxy reports for disability, as determined during a substudy in which 20 participants who were cognitively intact and their designated proxies were interviewed separately over the phone each month for six months, was excellent, with Kappa = 1.0 (22). Of the 56,266 monthly interviews, 10.5% were completed by a proxy informant.

Disability Subtypes

Our goal was to identify a set of distinct disability subtypes that were sufficiently common (i.e. comprise at least 10% of all disability subtypes) and clinically meaningful. We defined the disability subtypes on the basis of the number and duration of disability episodes whose onset occurred within an 18-month interval, i.e. the time between our comprehensive assessments. This time interval has high face validity since clinicians often use the next 12 to 24 months as a frame of reference when discussing prognosis with their older patients (19,33,34). In addition, many other longitudinal studies of disability have had assessment intervals ranging from 12 to 24 months (35). Based on the results of our prior research (17–19,36,37), review of the literature (38–40), clinical judgment, and preliminary review of the data from the monthly telephone interviews, we defined five distinct disability subtypes, as shown in the Appendix.

Appendix.

Operational Definitions of the Five Distinct Disability Subtypes

| Disability Subtype | Operational Definition* |

|---|---|

| Transient | One episode of disability lasting only one month |

| Short-term | One episode of disability lasting two to five months |

| Long-term | One or more episodes of disability, with at least one lasting six or more months |

| Recurrent | Two episodes of disability, with none lasting six or more months |

| Unstable | Three or more episodes of disability, with none lasting six or more months |

Defined in the context of 18-month intervals, as described in the text. The duration of a disability episode was based on the number of consecutive months of disability, as determined during the monthly telephone interviews.

For an 18-month interval to be included, participants had to be nondisabled at the start of the interval, as determined during the corresponding comprehensive assessment. This was necessary to identify incident cases, thereby ensuring temporal precedence when evaluating the association between physical frailty and the development of the disability subtypes in the current study and when identifying other potential risk factors and precipitants of the different disability subtypes in future studies. We excluded intervals for which there was no comprehensive assessment and those that were shorter than 12 months in duration, i.e. due to death, lost to follow-up, or end of the follow-up period. Of the 3,133 possible intervals, 630 (20.0%) were excluded for the following reasons: disability was present during the comprehensive assessment (n=497), duration of interval was shorter than 12 months (n=118), and the comprehensive assessment was not completed (n=15). When disability was present during the subsequent comprehensive assessment, we extended the 18-month interval to identify a disability subtype if the participant was disabled during the monthly interview immediately before and after this assessment. For example, a participant who became newly disabled in Month 15 and remained disabled for the next six months or more would fulfill criteria for long-term disability if s/he was disabled during the 18-month comprehensive assessment. Only 5.6% of the intervals were extended for this reason.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the frequency distributions of the five disability subtypes and no disability over all of the 18-month intervals combined and, subsequently, for each of the 18-month intervals separately over time. The unit of measurement for these analyses, unlike the subsequent analyses, was the 18-month interval rather than the participant. Because disability at the start of an interval was an exclusion criterion, the disability subtypes represent incident cases. When we reran these analyses using data from the first 356 enrolled participants who were randomly selected without sampling, the relative distribution of the disability subtypes did not change appreciably, although the proportion of intervals with no disability was modestly higher (results available upon request). To ensure that our results were not dependent on the selection of 18 months as the time interval, we compared the distribution of disability subtypes, using alternative intervals of 15 and 21 (i.e. 18 ± 3) months. Because comprehensive assessments were available only at 18-month intervals, this “sensitivity” analysis was limited to the first 21 months of follow-up.

Next, we calculated the cumulative incidence rates per 100 persons for each of the disability subtypes over the 18-month intervals according to age, sex, and physical frailty. For each incidence rate, we calculated 95% confidence intervals by bootstrapping samples with replacement, using the entire cohort. While point estimates, such as the cumulative incidence rates, are not subject to bias with repeated measures within subjects, the estimation of variance is. Bootstrapping with replacement is a robust method for estimating confidence intervals. One thousand samples were created, and the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles were used to form the confidence intervals. Finally, to determine whether the disability subtypes differ according to age, sex, and physical frailty, we ran multinomial logistic regression invoking generalized estimating equations (GEE) (41) using the procedure MULTILOG in SUDAAN (Release 9.0, Research Triangle Park, NC) with an exchangeable correlation structure. This analytic strategy accounts for the correlation within participants. The corresponding p-values, which were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Hochberg method (42), denote the statistical significance of each factor after adjusting for the other two factors.

To address the small amount of missing monthly data on disability (i.e. less than 1%), we used multiple imputation with 100 random draws per missing observation. Following recent recommendations for binary longitudinal data (43,44), we first imputed the probability of missingness based on a GEE logistic regression model with a pre-specified set of eight covariates (available upon request). We then imputed values for each missing month sequentially from the first month to the last month with a second pre-specified set of eight covariates (available upon request) along with the probability of missingness and the values for disability (present/absent) for each of the prior months.

All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. With the exception of the GEE multinomial logistic regression model, all analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were female, white, and did not live alone, while a sizeable minority were physically frail. There was a wide range of ages, education, and scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam, although the majority of participants completed high school and were cognitively intact. The median number of chronic conditions was 2, with the most common being hypertension and arthritis.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic* | N=754 |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median | 78 |

| Range | 70 – 96 |

| 80 years or older | 303 (40.2) |

| Female | 487 (64.6) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 682 (90.5) |

| Lives alone | 298 (39.5) |

| Education†, y | |

| Median | 12 |

| Range | 0 – 17 |

| Chronic conditions‡ | |

| Median | 2 |

| Range | 0 – 6 |

| Hypertension | 416 (55.2) |

| Arthritis | 227 (30.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 137 (18.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 136 (18.0) |

| Chronic lung disease | 132 (17.5) |

| Cancer | 124 (16.5) |

| Stroke | 65 (8.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 49 (6.5) |

| Hip fracture | 34 (4.5) |

| Physically frail | 322 (42.7) |

| Mini-Mental State Exam Score | |

| Median | 27 |

| Range | 12 – 30 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

17 years denotes postgraduate education.

Presented in descending order according to prevalence.

Of the 754 participants, 33 (4.4%) contributed no intervals to the analysis, largely because of death within the first 12 months of follow-up, while 131 (17.4%), 96 (12.7%), 93 (12.3%), 104 (13.8%), and 297 (39.4%) contributed one, two, three, four, and five intervals, respectively, as shown in the first two columns of Table 2. Of the 721 participants who contributed at least one interval, 243 (33.5%) had no disability during the follow-up period. Of the remaining 478 participants, 200 (41.8%), 90 (18.9%), 159 (33.3%), 106 (22.2%), and 95 (19.9%) had at least one interval with incident transient, short-term, long-term, recurrent, and unstable disability, respectively. Information on the number and percentage of participants with the occurrence of any disability subtype is shown in Table 2, according to the number of available intervals. Of the 297 participants having five intervals, representing 90 months of follow-up, the majority (51.5%) remained disability free, while another quarter (26.6%) had only a single interval with incident disability. About a quarter (24.7%) of all participants had two or more intervals with an incident disability subtype. Of the 478 participants having at least one interval with an incident disability subtype, 186 (38.9%) had a subsequent interval with disability.

Table 2.

Number and Percentage of Participants with the Occurrence of a Disability Subtype According to the Number of Available Intervals*

| Number of Intervals with an Incident Disability Subtype† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | ||

| Number of Available Intervals |

N | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| 1 | 131 | 37 (28.2) | 94 (71.8) | ||||

| 2 | 96 | 25 (26.0) | 39 (40.6) | 32 (33.3) | |||

| 3 | 93 | 9 (9.7) | 45 (48.4) | 24 (25.8) | 15 (16.1) | ||

| 4 | 104 | 19 (18.3) | 35 (33.7) | 27 (26.0) | 20 (19.2) | 3 (2.9) | |

| 5 | 297 | 153 (51.5) | 79 (26.6) | 37 (12.5) | 18 (6.1) | 8 (2.7) | 2 (0.7) |

Of the 754 participants, 33 (4.4%) contributed no intervals, largely because of death within the first 12 months of follow-up. Of the 721 participants who contributed at least one interval, 243 (33.5%) had no disability during the follow-up period.

The disability subtypes included transient, short-term, long-term, recurrent, and unstable, as described in the text. Because disability at the start of an interval was an exclusion criterion, the disability subtypes represent incident cases.

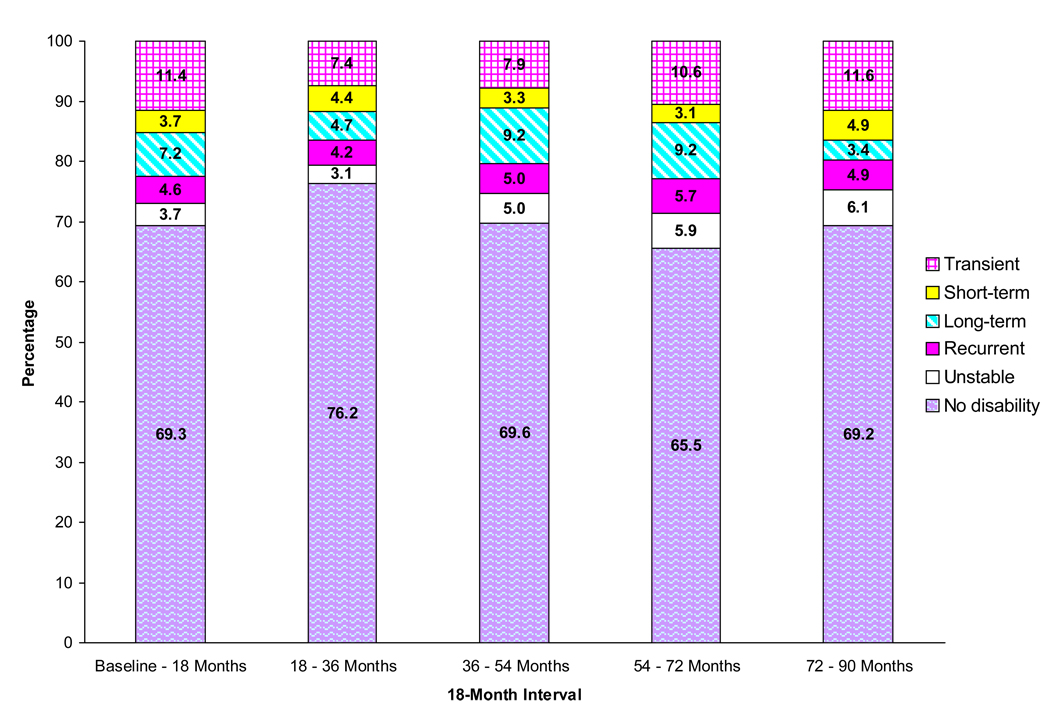

The distribution of the disability subtypes and no disability over all of the 2,503 intervals is shown in Figure 1. Incident disability was observed in about 30% of the intervals. The most common disability subtypes were transient and long-term. For the long-term subtype, the median duration of disability was 16 months, with an interquartile range of 8 to 35 months. Of the 172 intervals with long-term disability, 86 (50.0%) included disability lasting six or more months as its first or only disability episode, while 113 (65.7%) ended in death or persisted to the end of the follow-up period. Of the 113 intervals with unstable disability, 42 (37.2%) included four disability episodes, 15 (13.3%) included five, and 2 (1.8%) included six. As shown in Figure 2, the distribution of the disability subtypes and no disability changed relatively little over time, with no clear trends other than a modest increase in the likelihood of unstable disability. The distribution of the disability subtypes did not change appreciably when the time interval was redefined as either 15 or 21 months (results available upon request).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the disability subtypes and no disability over all of the 18-month intervals (N=2,503). The percentages do not add up to 100 because of rounding. Because disability at the start of an interval was an exclusion criterion, the disability subtypes represent incident cases. The unit of measurement was the 18-month interval.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the disability subtypes and no disability according to the 18-month interval. The percentages do not all add up to 100 because of rounding. Because disability at the start of an interval was an exclusion criterion, the disability subtypes represent incident cases. The unit of measurement was the 18-month interval.

Figure 3 provides the cumulative incidence rates (95% confidence intervals) per 100 persons for each of the disability subtypes over the 18-month intervals according to age, sex, and physical frailty, along with the corresponding p-values, which denote the statistical significance of each factor after adjusting for the other two factors as described in the Methods. With the exception of short-term disability, the rates of the disability subtypes were significantly higher for participants who were 80 years or older than for those who were 70 to 79 years. This age difference in rates was especially pronounced for long-term disability. While the rates for long-term, recurrent, and unstable disability were higher for women than men, these differences were not statistically significant in the adjusted analysis. Physical frailty was strongly associated with each of the disability subtypes, although the difference in rates was small for transient disability. The largest difference in rates was observed for long-term disability, which was unlikely to occur in the absence of physical frailty.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence rates (95% confidence intervals) per 100 persons for each of the disability subtypes over the 18-month intervals according to age, sex, and physical frailty. The p-values, which were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Hochberg method (42), account for the correlation within participants and denote the statistical significance of each of the three factors (age, sex, and physical frailty, respectively) after adjusting for the other two factors. The unit of measurement was the participant.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of community-living older persons, we have characterized five distinct subtypes of disability and have evaluated how the incidence of these subtypes differ according to age, sex, and physical frailty. The most common subtypes were transient disability, defined as a single disability episode lasting only one month, and long-term disability, defined as one or more disability episodes, with at least one lasting six or more months. While there were no gender differences in the incidence rates for any of the subtypes, differences in rates were observed for each subtype according to age and physical frailty, with only one exception, and were especially large for long-term disability.

Our study is unique in that data on disability were available every month for nearly eight years. This allowed us to identify subtypes of disability that cannot be easily distinguished by other studies with less frequent assessments. We defined the disability subtypes on the basis of the number and duration of disability episodes within intervals of 18 months, which was the time between our comprehensive assessments. This allowed us to determine how the subtypes differed according to physical frailty, an important attribute that has been previously linked to functional decline and disability (9,27,28), and will allow us to evaluate other potential risk factors and precipitants in future studies. While the presence of physical frailty substantially increased the likelihood of developing long-term, recurrent, and unstable disability, we found that it had only a modest effect on developing transient and short-term disability. These results suggest that the mechanisms underlying the different disability subtypes likely differ. In the setting of disability, for example, older persons who are physically frail are less likely to recover than those who are not physically frail (18), providing one possible explanation for the difference in results for long-term versus transient disability.

In prior studies, we have shown that disability commonly arises from a combination of predisposing factors that make one vulnerable and intervening illnesses or injuries that act as precipitants (21,45). Whether this model applies to each of the disability subtypes is uncertain, but should be the focus of future research. Additional research may also be warranted to evaluate the natural history and prognosis of the different disability subtypes. We have previously demonstrated, for example, that even brief periods of disability have considerable prognostic importance (34). Ultimately, the results of the current and future research may lead to an improved nosology of disability, as suggested by Guralnik and Ferrucci (5), that takes into account time course, recovery, severity, and modality of onset, and, in turn, to the development of new interventions designed to enhance independent function among older persons.

While not intended to be definitive, our subtypes were informed by prior research and clinical judgment. For example, we chose six months as the minimum duration to define episodes of long-term disability because this period is often used to predict recovery after a disabling event (18,39,40). Our operational definition of unstable disability, as three or more episodes of disability with none lasting six or more months (i.e. not long-term), was based on the theoretical construct proposed by Campbell and Buchner, as substantial fluctuations in function with minor external events (38). Recurrent disability was modeled after other clinically relevant outcomes, such as falls and urinary tract infections, which commonly recur over discrete periods of time. Finally, we distinguished between episodes of disability lasting only one month (i.e. transient) from those lasting two to five months (i.e. short-term) because this difference in duration is likely meaningful to older persons and their caregivers. Whether each of the five subtypes is truly distinct is an empirical question that will be addressed in subsequent epidemiologic and qualitative studies.

Despite the high reliability of our disability assessment, we recognize that some of the episodes of transient disability may simply reflect measurement error rather than a true change in functional status. However, the associations observed between transient disability and older age and physical frailty, respectively, diminish the likelihood of measurement error, which would have biased our results to the null. Of the five subtypes, the most heterogeneous was long-term disability, which varied considerably according to duration and the possible inclusion of shorter episodes of disability. Whether these distinctions warrant subdivision of the long-term subtype will be the focus of future research.

As in most prior studies, we operationalized disability as a dichotomous state (present/absent) and did not evaluate the severity of disability, as denoted by the number of disabled activities, or the specific activities that were disabled. We have evaluated the burden of disability in bathing, one of the most commonly disabled activites, in an earlier longitudinal study (37), and we hope to incorporate the severity of disability in future studies of disability subtypes. While focusing on 18-month intervals might be considered a limitation, the distribution of disability subtypes was not sensitive to modest changes in the duration of the time interval. About 16% of the intervals were excluded because disability was present during the relevant comprehensive assessment. However, the distribution of the disability subtypes in the first interval, which included all participants having at least 12 months of follow-up, did not differ appreciably from that in the subsequent intervals, suggesting that the exclusion of intervals likely had little meaningful effect on our results. Defining incident cases in the context of regularly-spaced intervals will facilitate subsequent studies designed to determine whether the risk factors and precipitants of the five disability subtypes differ.

We found that about a quarter of all participants had two or more intervals with an incident disability subtype. Because recurrent events within individuals are not independent (46), we used special statistical techniques to calculate and subsequently compare the cumulative incidence rates for the different disability subtypes. Recurrent events, such as disability, falls, delirium, and hospitalizations, are common in older persons, and analytic strategies that consider only the initial event are increasingly considered suboptimal (47).

The validity of our results is strengthened by the nearly complete ascertainment of disability and by the low rate of attrition for reasons other than death. Nonetheless, because the duration of follow-up differed among our study participants, one might argue that it would have been preferable to enroll new participants into the study every 18 months, using an open cohort design. The relative stability of the incidence rates for each of the disability subtypes over the course of nearly eight years, however, suggests that the results of our study, which used a traditional, closed cohort design, are valid. While our participants were members of a single health plan in a small urban area, the generalizability of our results is enhanced by our high participation rate, which was greater than 75%. Moreover, our study population reflects the demographic characteristics of older persons aged 70 years or older in New Haven county, which are comparable to the United States as a whole, with the exception of race (New Haven county has a larger proportion of non-Hispanic whites in this age group than the United States, 91% vs. 84%) (48).

Over the past several years, we have provided strong evidence to support an emerging paradigm of disability as reversible and often recurrent (17,18,22). By identifying distinct subtypes of disability, we hope to further enhance our understanding of the disabling process and spur additional research that embraces the inherent complexity of disability, with the goal of reducing the overall burden of disability among older persons.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Below is a checklist for all authors to complete and attach to their papers during submission.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

*Author 1 TMG |

Author 2 ZG |

Author 3 HGA |

Etc. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | |||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | |||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | |||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | |||||

| Patents | X | X | X | |||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | |||||

Authors can be listed by abbreviations of their names.

For “yes” × mark(s): give brief explanation below:

Dr. Gill serves on a Scientific Advisory Board for Daiichi-Asubio Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Author Contributions: Dr. Gill had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Gill.

Acquisition of data: Gill.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Gill, Guo, Allore.

Drafting of the manuscript: Gill, Guo, Allore.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Gill, Guo, Allore.

Statistical analysis: Guo, Allore.

Role of the Sponsors: The organizations funding this study had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Paula Clark, RN, Martha Oravetz, RN, Shirley Hannan, RN, Barbara Foster, Alice Van Wie, BSW, Patricia Fugal, BS, Amy Shelton, MPH, and Alice Kossack for assistance with data collection; Evelyne Gahbauer, MD, MPH for data management and programming; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for development of the participant tracking system; Linda Leo-Summers, MPH for assistance with Figure 1 and Figure 2; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

The work for this report was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560, R01AG022993). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). Dr. Gill is the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24AG021507) from the National Institute on Aging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, Beckett LA, et al. Social networks and disability transitions across eight intervals of yearly data in the New Haven EPESE. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1999;54B:S162–S172. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.3.s162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolinsky FD, Armbrecht ES, Wyrwich KW. Rethinking functional limitation pathways. Gerontologist. 2000;40:137–146. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mor V, Wilcox V, Rakowski W, et al. Functional transitions among the elderly: patterns, predictors, and related hospital use. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1274–1280. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6354–6359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Underestimation of disability occurrence in epidemiological studies of older persons: is research on disability still alive? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1599–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, et al., editors. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1995. NIH Pub. No. 95-4009; The Women's Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women with Disability. 1995

- 7.Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA, Camacho T, et al. The dynamics of disability and functional change in an elderly cohort: results from the Alameda County Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckett LA, Brock DB, Lemke JH, et al. Analysis of change in self-reported physical function among older persons in four population studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:766–778. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz S, Branch LG, Branson MH, et al. Active life expectancy. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1218–1224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198311173092005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaves PH, Garrett ES, Fried LP. Predicting the risk of mobility difficulty in older women with screening nomograms: the Women's Health and Aging Study II. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2525–2533. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Reynolds SL. Further evidence on recent trends in the prevalence and incidence of disability among older Americans from two sources: the LSOA and the NHIS. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1997;52B:S59–S71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.2.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seeman TE, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ. Social network characteristics and onset of ADL disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1996;51B:S191–S200. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.s191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vita AJ, Terry RB, Hubert HB, et al. Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1035–1041. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark DO, Stump TE, Hui SL. Predictors of mobility and basic ADL difficulty among adults aged 70 years and older. J Aging Health. 1998;10:422–440. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiner PA, Snowdon DA, Schmitt FA. The loss of independence in activities of daily living: the role of low normal cognitive function in elderly nuns. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:62–66. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM, Kurland B. The burden and patterns of disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2003;58:70–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291:1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, et al. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:575–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchner DM, Wagner EH. Preventing frail health. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability among community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1492–1497. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill TM, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Evaluating the risk of dependence in activities of daily living among community-living older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1995;50A:M235–M241. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin JS. Ambling towards Nirvana. Lancet. 2002;359:1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill TM, McGloin JM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Two recruitment strategies for a clinical trial of physically frail community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1039–1045. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, et al. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;55A:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state." A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill TM, Robison JT, Tinetti ME. Difficulty and dependence: two components of the disability continuum among community-living older persons. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:96–101. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodgers W, Miller B. A comparative analysis of ADL questions in surveys of older people. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 1997;52:21–36. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.21. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Covinsky KE, Hilton J, Lindquist K, et al. Development and validation of an index to predict activity of daily living dependence in community-dwelling elders. Med Care. 2006;44:149–157. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196955.99704.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill TM, Kurland BF. Prognostic effect of prior disability episodes among nondisabled community-living older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1090–1096. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, et al. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:445–469. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill TM, Allore HG, Hardy SE, et al. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill TM, Guo Z, Allore HG. The epidemiology of bathing disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1524–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell AJ, Buchner DM. Unstable disability and the fluctuations of frailty. Age Ageing. 1997;26:315–318. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubin JA, Han L, Fried TR. Triggered sampling could help improve longitudinal studies of persons with elevated mortality risk. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoenig H, Nusbaum N, Brummel-Smith K. Geriatric rehabilitation: state of the art. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1371–1381. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allison PD. Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07-136. Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. Missing Data. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M, Fitzmaurice GM. A simple imputation method for longitudinal studies with non-ignorable non-responses. Biom J. 2006;48:302–318. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill TM, Han L, Allore HG. Predisposing factors and precipitants for bathing disability among older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:534–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glynn RJ, Buring JE. Ways of measuring rates of recurrent events. BMJ. 1996;312:364–367. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo Z, Gill TM, Allore HG. Modeling repeated time-to-event health conditions with discontinuous risk intervals: an example of a longitudinal study on functional disability among older persons. Methods Inf Med. (In press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. [Accessed May 29, 2003];U.S. Census Bureau; American FactFinder. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov.