Abstract

A key feature of many adult stem cell lineages is that stem cell daughters destined for differentiation undergo several transit amplifying (TA) divisions before initiating terminal differentiation, allowing few and infrequently dividing stem cells to produce many differentiated progeny. Although the number of progenitor divisions profoundly affects tissue (re)generation, and failure to control these divisions may contribute to cancer, the mechanisms that limit TA proliferation are not well understood. Here, we use a model stem cell lineage, the Drosophila male germ line, to investigate the mechanism that counts the number of TA divisions. The Drosophila Bag of Marbles (Bam) protein is required for male germ cells to cease spermatogonial TA divisions and initiate spermatocyte differentiation [McKearin DM, et al. (1990) Genes Dev 4:2242–2251]. Contrary to models involving dilution of a differentiation repressor, our results suggest that the switch from proliferation to terminal differentiation is triggered by accumulation of Bam protein to a critical threshold in TA cells and that the number of TA divisions is set by the timing of Bam accumulation with respect to the rate of cell cycle progression.

Keywords: bam, spermatogenesis, Drosophila, transit amplifying cell division

Adult stem cells act throughout life to replenish differentiated cells lost to normal turnover or injury. In many adult stem cell lineages, stem cell daughters undergo transit amplifying (TA) mitotic division before terminal differentiation. The number of TA divisions strongly influences the capacity of adult stem cells to regenerate and repair tissues (1). In addition, strict limits on TA cell proliferation may help prevent accumulation of oncogenic replication errors. Defects in the mechanisms that count and limit the number of TA divisions may therefore predispose to cancer. Indeed, recent evidence points toward cancer initiating events occurring in TA cells in leukemia (2, 3).

Despite the importance for normal tissue homeostasis and cancer, the mechanisms that specify the number of TA divisions are not understood. Here, we use the Drosophila male germ line model adult stem cell lineage to investigate the mechanisms that normally set developmentally programmed limits on proliferation of TA cells. Drosophila melanogaster male germ line stem cells (GSCs) lie in a niche at the tip of the testis, attached to somatic hub cells, and are maintained by signals from the hub and flanking somatic stem cells (4–7). When a GSC divides, one daughter remains in the niche and self-renews, while the other is displaced away and initiates differentiation. The resulting differentiating gonialblast, which is enveloped by a pair of somatic cells, founds a clone of 16 spermatogonia through four synchronous TA divisions with incomplete cytokinesis. Soon after the fourth TA division, the resulting 16 germ cells undergo premeiotic DNA synthesis in synchrony and switch to the spermatocyte program of cell growth, meiosis, and terminal differentiation. As spermatocytes, the cells increase in volume 25-fold, take on a distinctive morphology, and turn on a unique gene expression program for spermatid differentiation (8) (Fig. 1A).

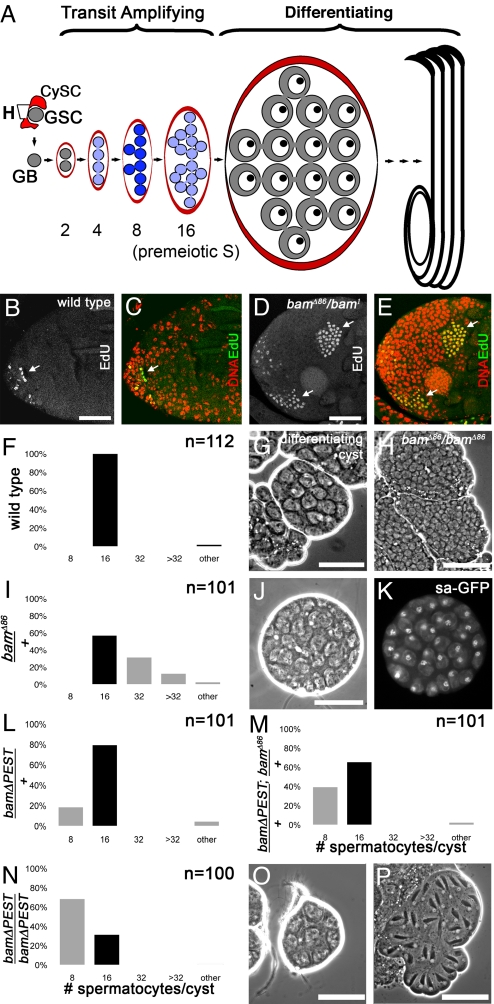

Fig. 1.

Timing of the switch from TA cell divisions to terminal differentiation depends on Bam dosage. (A) Scheme of normal differentiation of Drosophila melanogaster male germ cells. (Blue) Bam protein, (red) somatic cyst cells, and (CySC) cyst stem cells, (GSC) germ-line stem cell, (GB) gonialblast, (H) hub. (B–E) Cysts in S phase in wild-type or bamΔ86/bam1 mutant testes marked by a short pulse of EdU nucleotide analog staining (green) and colabeled with DAPI (red) in panels C and E. (B and C) Wild-type: Only germ cells at the anterior tip incorporate EdU (arrow). (D and E) bamΔ86/bam1: Germ cells undergo extra rounds of synchronous S phase in large cysts away from the tip (arrows). (F, I, L–N) Number of spermatocytes per cyst in indicated D. melanogaster genotypes. (Black bar) Normal 16 cells/cyst, indicating four rounds of division before differentiation. (F and G) Wild-type. (G) Phase contrast image of normal cyst of differentiating spermatocytes. (H) Phase contrast image of overproliferating spermatogonial cysts in bam mutant (note small size of cells compared to spermatocytes in panel G). (I–K) bamΔ86/+ heterozygotes. “Other” in panel I refers to one 26-cell cyst and one 30-cell cyst. (J and K) Cyst with 32 spermatocytes visualized by (J) phase contrast and (K) fluorescence imaging of Sa-GFP, a differentiation marker. (L–P) A bamΔPEST transgene caused premature spermatocyte differentiation. (L) bamΔPEST/+. (M) bamΔPEST/+; bamΔ86/+. (N) bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+. (O and P) Phase contrast images of bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+. (O) Eight-cell spermatocyte cyst. (P) Postmeiotic cyst with 32 spermatids instead of the normal 64 undergoing early elongation. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

The anatomy of developing germ cell cysts makes the Drosophila germ line especially well suited for investigating how the number of TA divisions is controlled. Because TA sister cells descended from a common gonialblast are contained within a common somatic cell envelope and divide in synchrony, the number of rounds of TA division executed prior to differentiation can be assessed by counting the number of differentiated spermatocytes per cyst (Fig. 1A). Also, because TA cells are easily distinguishable from spermatocytes, genetic manipulations that perturb the counting mechanism can be discriminated from those that cause failure of the switch from TA divisions to differentiation.

Two genes required in germ cells for spermatogonia to stop TA divisions and differentiate into spermatocytes are bag of marbles (bam) and benign gonial cell neoplasm (bgcn) (9, 10). Male germ cells mutant for bam or bgcn undergo several extra rounds of mitotic TA division (Fig. 1 D and E), fail to differentiate, and eventually die. Here we show that, in addition to being required for the switch from mitotic proliferation to meiotic differentiation, Bam also plays a role in counting the number of TA divisions. Our data suggest that timing of the switch from proliferation to differentiation is specified by accumulation of Bam protein to a critical level and the number of TA divisions is set by a combination of Bam accumulation and cell cycle length.

Results

The number of TA divisions before differentiation in the Drosophila melanogaster male germ line is tightly controlled. Counts of the number of spermatocytes per intact cyst confirmed that in wild-type, 99% of spermatocyte cysts counted had 16 cells (n = 112) (Fig. 1 F and G), indicating exactly four rounds of TA division. Comparisons between species suggested that the number of TA divisions is under genetic control; in Drosophila pseudoobscura, 96% of spermatocyte cysts scored (n = 49) had 32 cells, indicating five rounds of TA division.

In absence of bam, TA cells continued to proliferate and failed to differentiate, undergoing several extra rounds of mitotic division as reported in refs. 9 and 10. While wild-type testes incubated for 2 min with the nucleotide analog 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Edu) before fixation showed only 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, and 16-cell cysts in S phase at the tip of the testis, bam mutant testes also showed large cysts of 32 or more cells undergoing S phase far from the testis tip (Fig. 1 D and E compared to B and C, see also H compared to G). Two such overproliferating S-phase cysts scored had at least 150 cells, indicating more than seven rounds of TA division.

The number of TA divisions appears to be set by the timing of Bam protein accumulation. Male germ cells lacking one copy of bam (bamΔ86/+) usually made the transition from mitotic proliferation to spermatocyte differentiation, but often did so late; 43% of spermatocyte cysts had completed one or more extra TA divisions. Of 101 bam/+ spermatocyte cysts scored (Fig. 1I), 31% had exactly 32 cells/cyst and 12% had >32 cells/cyst (it was difficult to count spermatocyte number exactly in large cysts). Thirty-two-cell cysts expressed the spermatocyte-specific marker, Sa-GFP, indicating the germ cells had differentiated as spermatocytes (Fig. 1 J and K). The number of TA divisions was not affected in bgcn/+ males (100% 16-cell cysts, n = 49), suggesting that bam may be the limiting component.

Turnover of Bam protein may help control the rate of Bam accumulation. The Bam protein has a predicted C-terminal PEST sequence (10), a motif thought to target proteins for rapid turnover (11). Flies with one copy of a bamΔPEST transgene and wild-type at the endogenous bam locus had 9% (n = 102) to 18% (n = 101) (depending on the transgenic line) of cysts prematurely differentiate with eight cells (Fig. 1L). Flies with one copy of the stronger bamΔPEST transgene and heterozygous for bam had 39% eight-cell spermatocyte cysts (n = 101) (Fig. 1M). Flies with two copies of the stronger bamΔPEST transgene and wild-type for the endogenous bam locus had 68% eight-cell spermatocyte cysts (n = 100) (Fig. 1N). The eight-cell cysts had large cells with the typical spermatocyte morphology (Fig. 1O), suggesting that the switch to differentiation occurred successfully, although prematurely. Postmeiotic cysts were observed with 32 instead of the normal 64 elongating spermatids (Fig. 1P), confirming that germ cells from bamΔPEST animals progressed through the meiotic divisions and into spermatid differentiation. In contrast, flies that were wild-type for endogenous bam and carried two copies of a wild-type bam transgene (a 2.9-kb genomic fragment that rescues bam mutant male and female sterility) (10) had no eight-cell spermatocyte cysts (99% 16-celled cysts, n = 100), suggesting that the early differentiation observed upon deletion of the PEST sequence might be due to premature accumulation of the stabilized Bam protein rather than to increased gene dosage. Two extra copies of wild-type bam may not accumulate Bam protein early enough to cause a premature switch to differentiation, because bam is likely transcriptionally repressed in early germ cells via the TGFβ signaling pathway in males (12, 13), as has been documented in the female germ line (14, 15). Evasion of early transcriptional repression of bam by expression under control of a heat shock promoter caused premature differentiation (18% eight-cell cysts, n = 91) after heat shock (2 h at 37 °C on days 7 and 8, dissected day 11 after starting cultures). Flies of the same genotype without heat shock (n = 104) and wild-type flies heat-shocked using the same protocol (n = 100) produced no eight-cell cysts.

The pattern of Bam protein expression in testes was consistent with Bam accumulation setting the timing of the switch from spermatogonial proliferation to spermatocyte differentiation. By immunofluorescence staining on wild-type testes, Bam protein was detected in the cytoplasm of spermatogonia in 4-, 8-, and early 16-cell cysts, but not in stem cells, gonialblasts, or two-cell cysts (Fig. 2 A–F). Bam protein levels dropped abruptly in 16-cell cysts soon after premeiotic DNA replication. In wild-type testes costained with anti-PCNA to mark S phase, Bam protein was detected in 6/6 16-cell cysts undergoing premeiotic DNA replication, indicated by the punctate pattern of PCNA in the nucleus (Fig. 2 A–C, arrow). Bam protein levels dropped abruptly to background after premeiotic S phase, concomitant with or immediately preceeding loss of PCNA staining.

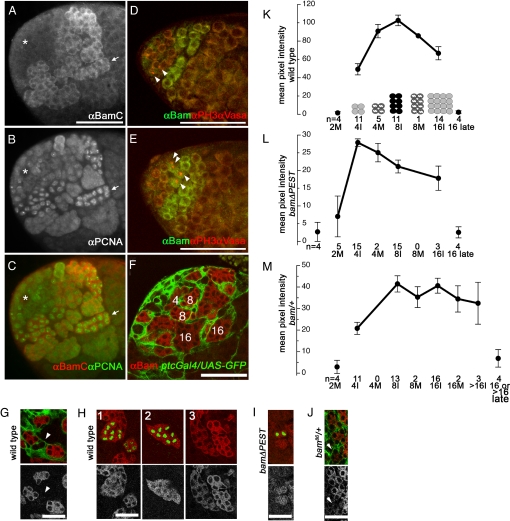

Fig. 2.

Bam protein levels peak during the cell cycle before differentiation. (A–C) Immunofluorescence image of testis apical tip stained with (A) anti-BamC and (B) anti-PCNA. (C) Merge. (Arrow) Sixteen-cell cyst in premeiotic S phase (punctate PCNA staining). (*) Hub. (D and E) Immunofluorescence images of wild-type testes stained with anti-PH3 (red), anti-Vasa (red), and anti-BamC (green). (D) (Arrowheads) Two-cell mitotic cyst positive for PH3 and negative for Bam. (E) (Arrowheads) Four-cell mitotic cyst positive for PH3 and Bam. (F–J) Immunofluorescence images of squashed testis stained with anti-Bam. (F) (Numbers) Numbers of cells/cyst determined by Bam stain (red) and by ptcGal4/UASgfp somatic marker (green) used to outline each cyst. (G) Three wild-type four-cell cysts positive for anti-Bam (red, Top and in black and white, Bottom) and one two-cell cyst negative for anti-Bam (arrowhead). Cysts outlined with ptcGal4/UASgfp (green). (H) Representative wild-type cysts used to quantify Bam protein levels in spermatogonia in Fig. 2K stained with anti-Bam (red, Top and in black and white, Bottom) and anti-PH3 (green). (H1) Four-cell and eight-cell mitotic cysts, (H2) eight-cell mitotic cyst, and (H3) three interphase cysts; (Left) 16-cell, (Upper Right) 4-cell, and (Lower Right) 8-cell. (I) bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ testes with two-cell mitotic cyst positive for Bam (only one observed). (J) bam/+ four-cell cysts. Two anti-Bam positive (Upper) and one negative (arrowhead) identified by ptcGal4/UASgfp (green). (K–M) Mean levels of Bam immunofluorescence through TA divisions in (K) wild-type and (L) bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST and in (M) bam/+. (Isolated points) Background fluorescence measurements from cysts before and after Bam expression, (M) mitotic, and (I) interphase cysts. Note: Scales differ because separate aliquots of Bam antibody were used to quantify Bam in each experiment. Error bars, SEM. [Scale bars, (A–F) 50 μm and (G–J) 25 μm.]

Bam protein accumulated to levels detectable by antibody staining early in four-cell cysts. Bam protein was not detected in any (0/6) two-cell mitotic anti-phospho histone H3 (PH3) positive cysts (Fig. 2D, arrowheads), but was detected in all (4/4) four-cell mitotic cysts scored from whole mount preparations (Fig. 2E, arrowheads). Consistent with this, in squashed preparations where cysts were separated from each other and somatic cells were labeled with ptc-Gal4/UAS-GFP to outline cysts, 0/5 two-cell cysts and 9/9 four-cell cysts had Bam protein (Fig. 2G). The four-cell cysts outlined with the somatic cell marker showed a variety of Bam levels from low to high, consistent with early onset and then increasing levels of Bam protein during the four-cell stage.

In immunofluorescence images of squashed preparations with ptc-Gal4/UAS-GFP, Bam immunofluorescence appeared to be low in four-cell cysts, higher in eight-cell cysts, and lower again in 16-cell cysts (Fig. 2F). To quantify anti-Bam immunofluorescence in different stage cysts, squashed testis preparations where individual cysts were separated were stained with anti-Bam and anti-PH3 to mark mitosis. The mean anti-Bam fluorescence signal per pixel (see Materials and Methods) was quantified in the cytoplasm of individual 4-, 8-, and early 16-cell interphase or mitotic (anti-PH3 positive) cysts (Fig. 2H). In wild-type, Bam levels were low in interphase four-cell cysts (note, only Bam positive cysts at this stage could be scored), increased in mitotic four-cell cysts, reached a peak during interphase eight-cell cysts, decreased slightly in early 16-cell cysts, then abruptly decreased in later 16-cell cysts (Fig. 2K).

Measurements of anti-Bam immunofluorescence in individual cysts in males carrying the bamΔPEST transgene indicated that Bam protein accumulated to a peak earlier in this genotype, consistent with the earlier switch from spermatogonia to spermatocytes. In bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ testes, one out of the five 2-cell PH3 positive cysts scored had positive Bam staining, although levels were low (Fig. 2I) and levels of Bam protein peaked in four-cell interphase cysts in bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ testes (Fig. 2L). Although it was not possible to compare absolute levels of Bam protein between wild-type and bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ testes in the two separate experiments, the timing of Bam accumulation was clearly shifted earlier in flies carrying the bamΔPEST transgene.

In bam/+ males with half the bam gene dosage, the Bam protein accumulated to detectable levels later in the four-cell stage than in wild-type. Using ptc-Gal4/UAS-GFP to outline cysts so they could be identified regardless of Bam status, 0/7 two-cell and only 8/13 four-cell cysts scored had Bam protein in bam/+ males (Fig. 2J) as compared with all four-cell cysts in wild-type. In the same preps, Bam fluorescence was observed in PH3+ 16-cell and >16-small-cell cysts. Measurements of anti-Bam immunofluorescence in cysts from bam/+; ptc-Gal/UAS-GFP males showed peak Bam levels at the eight-cell and again at the 16-cell stage (Fig. 2M), consistent with two populations of cells, one population that would differentiate as 16-cell cysts and another population that would differentiate as 32 or >32-cell cysts as observed by phase contrast microscopy (Fig. 1I).

Manipulation of cell cycle regulators in spermatogonia indicated that the number of TA divisions in the male GSC lineage may be specified by interplay between the timing of Bam accumulation and cell cycle length. A transgene expressing Gal4 (16) under control of the bam promoter drove expression of a UAS-GFP reporter starting in late spermatogonial cysts (Fig. S1). When a positive regulator of the G2/M transition, string (stg), a homolog of S. pombe cdc25 (17), was forcibly expressed in late TA cells using bamGal4, cells in 97% of cysts completed one or two (but never more) extra rounds of TA division before differentiating (n = 100 cysts). Sixty-five percent of the spermatocyte cysts had exactly 32 cells/cyst. In addition, 21% had between 16 and 32 cells/cyst, suggesting that a subset of cells underwent an extra division (Table S1), and 11% had >32 cells/cyst (Fig. 3 A and B).

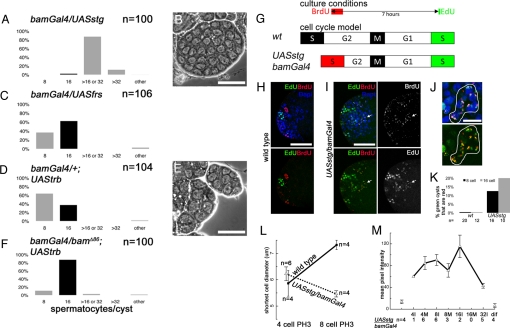

Fig. 3.

Forced expression of cell cycle regulators affects the number of TA divisions. (A, C, D, and F) Percentage of cysts with indicated number of spermatocytes/cyst for a given genotype. (A and B) Forced expression of UASstg during TA divisions using bamGal4. (B) Phase contrast image of cyst with 32 differentiating spermatocytes from bamGal4/UASstg. (C–E) Forced expression of cell cycle inhibitors (C) UASfrs or (D and E) UAStrb using bamGal4 produced many eight-cell cysts. (E) Phase contrast image of cysts with eight differentiating spermatocytes from UAStrb/bamGal4. (F) One copy of bamΔ86 partially suppressed the UAStrb/bamGal4 eight-cell phenotype. (G–K) Double S-phase label showed that forced expression of String shortened cell cycle. (G) Experimental scheme. (H–J) Testes stained for EdU (green), BrdU (red), and DAPI (DNA, blue). (H) Wild-type: EdU and BrdU are in separate cysts. (I) UASstg/bamGal4: EdU and BrdU colocalize in some 8- and 16-cell cysts (arrow). (J) High magnification view of 16-cell cyst marked with arrow in I. (K) Percentage of cysts labeled with EdU that also labeled with BrdU. P = 0.035 for 8- and 16-cell cysts together (Fisher exact test). P = 0.190 for only 8-cell, and P = 0.195 for only 16-cell. (L) Cell size as measured by shortest diameter in wild-type and UASstg/bamGal4 four-cell and eight-cell mitotic (PH3+) cysts; n = number of cysts quantified. (M) Levels of Bam immunofluorescence in TA cell cysts from UASstg/bamGal4 testes. (Isolated points) Background fluorescence measurements from cysts before and after Bam expression, (M) mitotic, and (I) interphase cysts. [Scale bars, (B, E, H, and I) 50 μm and (J) 12.5 μm.]

Conversely, when the cell cycle inhibitor fruhstart (frs) (18) was forcibly expressed using bamGal4, 36% of cysts differentiated with eight spermatocytes rather than 16 (n = 106) (Fig. 3C). Similarly, forced expression of the cell cycle inhibitor tribbles (trb), which causes degradation of Stg (19), resulted in 63% eight-cell cysts (n = 104 cysts) (Fig. 3 D and E). The effect of forced expression of trb was suppressed by reducing the bam dosage by half; the frequency of eight-cell spermatocyte cysts decreased from 63 to 10%, and the frequency of 16-cell spermatocyte cysts increased from 37% to 87% in bamGal4/bamΔ86; UAStrb testes (Fig. 3F). Also, decreasing bam dosage slightly enhanced the overproliferation caused by forcibly expressed string; the frequency of spermatocyte cysts with >32 cells/cyst increased from 11% to 27% (Fig. S2). Forced expression of frs in early female germ cells using bamGal4 caused many differentiated cysts (egg chambers) to have eight cells (Table S2), analogous to the effect of forced frs expression in males, indicating some similarities in the mechanisms that regulate the number of TA divisions in the male and female germ line. However, there are also clear differences between the sexes, as loss of function of enc did not alter the number of TA divisions in males as it does in females (20) (see Table S2 for this and other examples).

Measurements of S-phase timing in male TA cells indicated that forcible expression of Stg in late TA cells shortened cell cycle length, allowing the extra rounds of TA division observed. In double pulse label experiments, testes dissected from wild-type or UASstg/bamGal4 flies were incubated with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 15 min, washed extensively, and incubated in culture medium. Seven hours after BrdU was initially added, testes were labeled with Edu for 5 min and then fixed (Fig. 3G) (see SI Text for details). For wild-type, of the twenty 8-cell and 12 16-cell S-phase cysts labeled with EdU scored, none had also incorporated BrdU, indicating that wild-type four- and eight-cell cysts take longer than 7 h to complete one cell cycle (Fig. 3 H and K). In UASstg/bamGal4 testes, of the 26 cysts labeled with EdU scored, 2/16 eight-cell and 2/10 16-cell cysts also had incorporated BrdU (Fig. 3 I–K), indicating that they had progressed from S phase to S phase in the time between the two pulse labels.

A decrease in cell size in late TA cells from UASstg/bamGal4 testes compared to wild-type was consistent with a shortened cell cycle time. In wing disc cells, shortening of G2 is compensated for by lengthening of G1, keeping the cell cycle length and cell size constant (21, 22). However, spermatogonia expressing UASstg/bamGal4 became smaller, suggesting total cell cycle length (not just G2) was shorter. In squashed preparations of wild-type and UASstg/bamGal4 testes stained for the mitotic marker (PH3) and for Bam (as in Fig. 2H), four-cell cysts undergoing mitosis were the same size, probably because Stg expression under control of bamGal4 may not start until late in the four-cell stage. However, although cell size slightly increased from four-cell M-phase to eight-cell M-phase in wild-type, cell size slightly decreased from four-cell M-phase to eight-cell M-phase in UASstg/bamGal4 testes (Fig. 3L), consistent with the cell cycle shortening indicated by the double pulse label experiments (Fig. 3 G–K). Shortened cell cycles in late TA cysts due to forced expression of stg may allow more rounds of division to take place before Bam reaches its peak. Consistent with this possibility, measurement of Bam protein levels showed high Bam protein in early 16-cell cysts in bamGal4/UASstg testes (Fig. 3M).

Discussion and Conclusion.

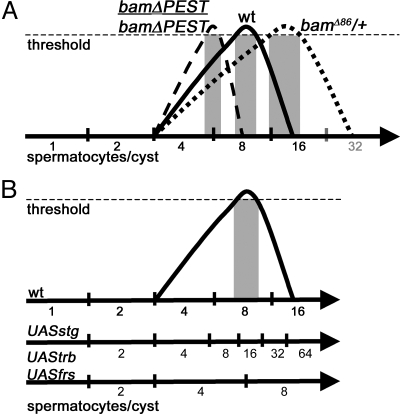

We propose that the switch from spermatogonial TA divisions to the spermatocyte differentiation program may be triggered by accumulation of Bam protein to a critical threshold and that the number of TA divisions is set by interplay between the timing of Bam protein accumulation and cell cycle length. A slower rate of accumulation of Bam protein in bam/+ germ cells may allow one or more extra rounds of mitotic division before differentiation (Figs. 2M and 4A). Likewise, cell cycle shortening by forced expression of string may allow more rounds of division to take place before Bam protein reaches the critical threshold (Fig. 4B), resulting in spermatocyte cysts with 32 or more cells. Conversely, premature accumulation of Bam protein in spermatogonia observed in bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ testes (Figs. 2L and 4A) may allow the switch to occur early, resulting in eight-cell spermatocyte cysts.

Fig. 4.

Model. (A) Model: Bam protein accumulation to a critical threshold triggers the switch to spermatocyte fate following the next mitotic division, producing 16-cell spermatocyte cysts in wild-type. Bam reaches the threshold later in bamΔ86/+, producing many cysts with 32 or more spermatocytes. In bamΔPEST/bamΔPEST; +/+ flies, stabilized Bam protein reaches the threshold earlier, producing many cysts with eight spermatocytes/cyst. (B) Model of how manipulation of cell cycle timing may produce different numbers of TA divisions.

In wild-type, Bam levels appear to peak in the eight-cell stage (Fig. 2K), before the last mitotic division and considerably before Bam is down-regulated. We suggest that accumulation of Bam to a threshold in G2 of the eight-cell stage may cause germ cells to initiate the spermatocyte program after completing the eight-cell M-phase. As a result, 16-cell cysts execute premeiotic DNA replication, then enter meiotic prophase. The subsequent abrupt down-regulation of Bam protein may be a downstream effect of initiating the spermatocyte program.

Threshold Bam levels may be required for differentiation, because Bam may need to fully titrate an inhibitor to trigger the switch to differentiation. Recent studies indicate that Bam and its partner Bgcn act by translational repression and suggest an antagonistic role with the translational initiation factor eIF4a (23, 24). As cysts from eIF4a/+; bam/+ testes overproliferate less than cysts from bam/+ sibling control testes [8/94 (9%) as compared to 28/87 (32%); Table S3], it will be interesting to explore whether eIF4a, some other component involved in translational control, or an mRNA encoding an inhibitor of differentiation might set the threshold requirement for Bam. Interestingly, although bam is not required for male germ cells to initiate TA divisions, forced early expression of bam is sufficient to drive GSCs to differentiation (25) or at high sustained levels, to death (26). These observations suggest that Bam may have a variety of targets and that timing and levels of expression of this potent regulator must be tightly controlled for normal differentiation in the male GSC lineage.

Accumulation of a critical differentiation factor to a threshold may also limit TA divisions and trigger the switch to differentiation in certain mammalian stem cell lineages. In oligodendrocyte precursor cells, which also have a restricted number of divisions, accumulation of a cdk inhibitor triggers differentiation. Although the molecular identity of the factor accumulating is different, the regulatory logic is similar (27).

Materials and Methods

Fluorescence Quantification.

Testes from newly eclosed males for all genotypes were fixed in squashed preparations and stained with anti-Bam. A sample subset was also stained with anti-PH3. Another sample subset expressed the somatic cell marker ptcGal4/UAS-GFP. Cysts (as in Fig. 2 F–J) were imaged in a single plane. The mean fluorescence intensity/pixel of several nonoverlapping 12 × 12 pixel areas in the cyst cytoplasm was measured and averaged for each cyst. The mean background fluorescence/pixel of tissue in which Bam was not expressed was subtracted from each cyst measurement. Finally, for each cyst type (four-cell, four-cell dividing, eight-cell, eight-cell dividing, 16-cell), the measurements of mean cyst pixel fluorescence were averaged, and the standard error of the mean (SEM) calculated.

See SI Text for more details on fly strains and husbandry, heat shock, generation of transgenic flies with the BamΔPEST, live cyst dissection, immunostaining, fluorescence quantification, measuring cell cycle timing by double S-phase label of dissected testes, and measuring cell size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Tony Mahowald and Catherine Baker for helpful comments. This work was supported by a California Institute of Regenerative Medicine predoctoral fellowship, the Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program Grant GM007365, and the National Institutes of Health Grants GM080501 and GM45820.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0912454106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Clarke MF, Fuller M. Stem cells and cancer: Two faces of eve. Cell. 2006;124:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krivtsov AV, et al. Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL-AF9. Nature. 2006;442:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature04980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson CH, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:657–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–754. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tulina N, Matunis E. Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science. 2001;294:2546–2549. doi: 10.1126/science.1066700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller MT, Spradling AC. Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: Two versions of immortality. Science. 2007;316:402–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1140861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Zfh-1 controls somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila testis and nonautonomously influences germline stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller MT. Spermatogenesis. In: Martinez-Arias MBA, editor. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 71–147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonczy P, Matunis E, DiNardo S. bag-of-marbles and benign gonial cell neoplasm act in the germline to restrict proliferation during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 1997;124:4361–4371. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKearin DM, Spradling AC. bag-of-marbles: A Drosophila gene required to initiate both male and female gametogenesis. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2242–2251. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers S, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: The PEST hypothesis. Science. 1986;234:364–368. doi: 10.1126/science.2876518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shivdasani AA, Ingham PW. Regulation of stem cell maintenance and transit amplifying cell proliferation by tgf-beta signaling in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2065–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawase E, Wong MD, Ding BC, Xie T. Gbb/Bmp signaling is essential for maintaining germline stem cells and for repressing bam transcription in the Drosophila testis. Development. 2004;131:1365–1375. doi: 10.1242/dev.01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D, McKearin DM. A discrete transcriptional silencer in the bam gene determines asymmetric division of the Drosophila germline stem cell. Development. 2003;130:1159–1170. doi: 10.1242/dev.00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen D, McKearin D. Dpp signaling silences bam transcription directly to establish asymmetric divisions of germline stem cells. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelps CB, Brand AH. Ectopic gene expression in Drosophila using GAL4 system. Methods. 1998;14:367–379. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edgar BA, O'Farrell PH. Genetic control of cell division patterns in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1989;57:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosshans J, Muller HA, Wieschaus E. Control of cleavage cycles in Drosophila embryos by fruhstart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rorth P. Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell. 2000;101:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins NC, Thorpe J, Schupbach T. Encore, a gene required for the regulation of germ line mitosis and oocyte differentiation during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1996;122:281–290. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neufeld TP, de la Cruz AF, Johnston LA, Edgar BA. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 1998;93:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reis T, Edgar BA. Negative regulation of dE2F1 by cyclin-dependent kinases controls cell cycle timing. Cell. 2004;117:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Minor NT, Park JK, McKearin DM, Maines JZ. Bam and Bgcn antagonize Nanos-dependent germ-line stem cell maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9304–9309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901452106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen R, Weng C, Yu J, Xie T. eIF4A controls germline stem cell self-renewal by directly inhibiting BAM function in the Drosophila ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11623–11628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903325106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheng XR, Brawley CM, Matunis EL. Dedifferentiating spermatogonia outcompete somatic stem cells for niche occupancy in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz C, et al. A misexpression screen reveals effects of bag-of-marbles and TGF beta class signaling on the Drosophila male germ-line stem cell lineage. Genetics. 2004;167:707–723. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dugas JC, Ibrahim A, Barres BA. A crucial role for p57(Kip2) in the intracellular timer that controls oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6185–6196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0628-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.