Abstract

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a common human genetic disease with severe medical consequences. Although it is appreciated that the cilium plays a central role in PKD, the underlying mechanism for PKD remains poorly understood and no effective treatment is available. In zebrafish, kidney cyst formation is closely associated with laterality defects and body curvature. To discover potential drug candidates and dissect signaling pathways that interact with ciliary signals, we performed a chemical modifier screen for the two phenotypes using zebrafish pkd2hi4166 and ift172hi2211 models. pkd2 is a causal gene for autosomal dominant PKD and ift172 is essential for building and maintaining the cilium. We identified trichostatin A (TSA), a pan-HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitor, as a compound that affected both body curvature and laterality. Further analysis verified that TSA inhibited cyst formation in pkd2 knockdown animals. Moreover, we demonstrated that inhibiting class I HDACs, either by valproic acid (VPA), a class I specific HDAC inhibitor structurally unrelated to TSA, or by knocking down hdac1, suppressed kidney cyst formation and body curvature caused by pkd2 deficiency. Finally, we show that VPA was able to reduce the progression of cyst formation and slow the decline of kidney function in a mouse ADPKD model. Together, these data suggest body curvature may be used as a surrogate marker for kidney cyst formation in large-scale high-throughput screens in zebrafish. More importantly, our results also reveal a critical role for HDACs in PKD pathogenesis and point to HDAC inhibitors as drug candidates for PKD treatment.

Keywords: chemical suppressor, zebrafish

Affecting >600,000 Americans and an estimated 12.5 million people worldwide, polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is characterized by the formation of multiple epithelium-lined cysts in the kidney (1). The autosomal dominant form of this disease (ADPKD) is caused by mutations in either PKD1 or PKD2 and affects one in 1,000 live births (2, 3). ADPKD is among the most common monogenetic disorders and more than half of the patients progress into end stage renal disease by age 60 (1). Recent progress in the PKD field points to a central role of ciliary defects in PKD pathogenesis. In this model, the cilium, a cell surface organelle, functions as a sensor for environmental antiproliferation signals (4–6). Ciliary defects can therefore lead to epithelial over-proliferation and eventual cyst formation. However, how ciliary signals are coupled to downstream cellular events remains poorly understood.

Presently, no directed therapy is available for PKD. It is a slow-progressing disease, however, that frequently takes decades to develop symptoms. Therefore, a treatment of even modest efficacy could have significant clinical impact.

The zebrafish Danio rerio has emerged as an excellent system to model PKD. Forward genetic screens in zebrafish have identified multiple homologs of human PKD genes, such as PKD2 and vHNF1, as causal genes for cystic kidney phenotypes when disrupted, validating the relevance of kidney cyst formation in zebrafish to human PKD (7, 8). Moreover, zebrafish embryos are transparent and develop ex utero, making them highly amenable to high-throughput genetic and chemical screens.

In addition to a robust model system, a high-throughput screen (HTS) requires an easily recognizable readout that is tightly associated with the question being analyzed. In zebrafish PKD models, the relative small size and variability of kidney cysts is challenging as a reliable HTS readout. However, recent studies have demonstrated that defects in cystic kidney genes lead to additional morphological phenotypes, most prominently body axis curvature and defective left-right (LR) asymmetry of the body plan (7, 9, 10). For example, in two genetic mutagenesis screens for cystic kidney mutants, 12 out of 15 and 10 out of 12 of isolated mutants displayed concomitant curved body phenotypes, respectively (7, 11). Strikingly, an insertional mutant of the ADPKD gene pkd2, pkd2/hi4166, shows dorsally curved body axis and defective laterality, while morphants (knockdown animals generated by morpholino antisense oligo) additionally display kidney cyst formation (7). Moreover, multiple mutants of ift genes, such as ift172/hi2211, which encode components of the intraflagellar transport particles that are essential for the formation and function of the cilium, present cystic kidney and a ventrally curved body axis (7), while morphants for these genes also show a defect in LR asymmetry (10). The phenotypic similarity of these cystic kidney mutants is likely due to the convergence of these genes' functions on ciliary signaling (4–6). Given the close association between kidney cyst formation and defective laterality and body curvature phenotypes in zebrafish, we hypothesized that these easily recognizable morphological phenotypes could be used as a surrogate marker for kidney cyst formation in a visual screen.

Accordingly, to identify chemical tools for PKD research and leads for drug discovery, we performed a chemical modifier screen for body curvature and laterality phenotypes in zebrafish by applying a collection of compounds with known biological activities to pkd2/hi4166 and ift172/hi2211 embryos. From this screen, we identified six compounds that modulated body curvature and 14 that disrupted laterality. Interestingly, three out of the six curvature hits were also positive hits for the laterality phenotype. TSA (tricho statin A) is particularly interesting in that it is a potent pan HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitor and that it is among the three hits that affected both phenotypes. We further showed that both treatment of VPA, another HDAC inhibitor whose structure is unrelated to TSA, and knockdown of hdac1 suppressed pkd2 phenotypes. Importantly, either TSA or VPA inhibited kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants. We next tested the efficacy of VPA in modulating the polycystic kidney phenotype in mouse models based on conditional inactivation of the mouse ortholog of human PKD1. VPA was able to reduce the progression of cyst formation and slow the decline of kidney function in Pkd1 mutant mice. These results validated the use of morphological phenotypes, especially body curvature, as a surrogate marker for cystic kidney defects. To aid in the identification and quantification of the zebrafish body curvature phenotype, we developed a computer algorithm that can reliably classify individual animals among group pictures automatically, making it feasible to perform large-scale HTS for compound suppressors in the future. Significantly, as VPA is a class I HDACs inhibitor (12–14) and hdac1 encodes a class I HDAC, our results indicate that class I HDACs play a critical role in PKD pathogenesis and suggest that HDAC inhibitors may be excellent drug candidates for PKD treatment.

Results

A Small Chemical Library That Targets a Diverse Set of Biological Pathways.

Multiple compound libraries are commercially available. Many of these libraries target a subset of biological activities, such as kinases or channels, or consist of natural products, FDA approved drugs or large collections with structurally diverse compounds of unknown targets. To identify known signaling pathways that intersect with the ill-defined PKD-ciliary signaling pathway(s), we reasoned that a small library comprised of well-defined compounds that are biologically potent and target a wide array of signaling pathways would be advantageous. We therefore assembled a custom library of 115 compounds, targeting cell cycle progression, apoptosis, actin and microtubule cytoskeleton, calcium signaling, vesicle trafficking, multiple receptor kinases mediated pathways, posttranslational modification, protein degradation, and chromatin remodeling.

Compounds that Modify the Body Curvature Phenotype in Zebrafish.

Using the above-mentioned library, we screened for compounds that can affect body curvature in zebrafish. We first applied this library to embryos from heterozygous pkd2/hi4166 carriers, a quarter of which are homozygous mutants, while the rest are homozygous wild-type or heterozygous carriers. The pkd2/hi4166 mutant displays a LR asymmetry defect, indicated by randomized heart jogging at 30 h post fertilization (hpf) (Fig. S1 A–C), and a dorsally curved body axis (Fig. S1 D and E) (7). We determined the concentration for each compound empirically. Briefly, chemicals were added at a starting concentration of 10×IC50. If a chemical at a given concentration caused severe neocrosis or lethality of treated embryos, a lower concentration was used in subsequent tests. If, however, no morphological phenotype was observed, increased concentrations were used until visible phenotypes were observed. To provide collaborative and possibly comparative results from an independent PKD model, we carried out the same screen by applying compounds at the optimized concentration to ift172/hi2211 mutants, which display a ventrally curved body axis and kidney cyst formation (Fig. S1F) (7).

Through the screen, we identified six compounds that affected body curvature and categorized them into three distinct groups (Table S1). The first group is capable of enhancing the dorsal curvature regardless of genetic backgrounds. Specifically, a Cox2-inhibitor, a CaM kinase II inhibitor and a CFTR inhibitor caused dorsal curvature in wild-type embryos, exaggerated dorsal curvature in pkd2/hi4166 mutants and reversed ventral curvature to dorsal curvature in ift172/hi2211 mutants (Fig. S1 G and H and Table S1). The second group affected pkd2/hi4166 more significantly than ift172/hi2211. Specifically, a HDAC inhibitor (trichostatin A) and a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, which reversed dorsal curvature to ventral curvature in pkd2/hi4166, did not affect the curvature in ift172/hi2211 significantly (Table S1). The third group, which consists of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, altered the body axis of ift172/hi2211 from curled down to curled up (Table S1).

Compounds That Affect Laterality of the Body Plan.

We next screened for compounds that affect laterality in zebrafish by scoring heart position on 1 day post fertilization (dpf). In total, we identified 14 chemical compounds that disrupted LR asymmetry. These compounds were initially identified because they increased the percentage of embryos with laterality defects in crosses of heterozygous pkd2/hi4166 carriers. Positive hits were then verified with embryos from wild-type crosses. Therefore, these hits represent compounds that disrupt LR asymmetry in wild-type embryos. Seven of the hits target signal pathways already implicated in establishing LR asymmetry, including TGF-β signaling (15) (TGFβRI Inhibitor), calcium signaling (16, 17) (K-252a, Thapsigargin), cAMP signaling (18) (IBMX, Etazolate), and the microtubule cytoskeleton (19, 20) (nacodazole and paclitaxel) (Table S1). Interestingly, taxol was shown to slow the progression of kidney cyst formation in cpk mouse, a recessive PKD model (21). The connection between the remaining hits and LR is less obvious and may provide directions for future studies (Table S1). Importantly, three of the 14 hits were also isolated from the body curvature screen, including TSA, a Cox-2 inhibitor, and a CaM kinase II inhibitor (Table S1). These three common hits might be excellent candidates as chemical modifier of kidney cyst formation.

Tricostatin A, A Pan HDAC Inhibitor, Can Suppress the Body Curvature Phenotype of pkd2 Mutants.

Among the positive hits we isolated, TSA is particularly interesting in that it affects both body curvature and LR asymmetry and is a potent inhibitor of HDACs (22). We therefore tested it more extensively, which revealed that the effect of TSA on embryo development is both dosage-dependent and sensitive to developmental stages. For example, wild-type embryos treated from the 30% epiboly stage displayed increasingly severe downward body curvature as the dosage of TSA increased from 200 to 500 nM (Fig. S2A), whereas embryos treated with 500 nM TSA from the shield stage showed only a mild body curvature phenotype (Fig. 1 A and B), those treated from 27 hpf with 500 nM TSA showed no curvature at all (Fig. 1 C and D).

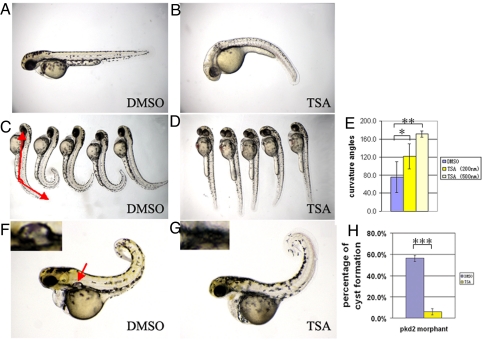

Fig. 1.

Suppression of pkd2 mutants/morphants by TSA. (A and B) Treatment of 500 nM TSA from the shield stage leads to slight ventral curvature (B) on 2 dpf in wild-type embryos (wt) as compared to embryos treated with DMSO (A). (C–E) TSA can suppress the body curvature of pkd2/hi4166 mutant embryos. (C) shows mutant embryos treated with DMSO from 27 hpf on 2 dpf. Red lines depict the definition of curvature angle. (D) shows embryos treated with 500 nM TSA from 27 hpf on 2 dpf. With this treatment, mutant embryos are indistinguishable from wild-type siblings. (E) Average curvature angle in embryos treated with DMSO, 200 and 500 nM TSA. n = 5, *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.0005. (F–H) Inhibition of kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants (pkd2mo) on 3 dpf by treatment of 100 nm TSA from the bud stage. (F) shows a pkd2 morphants treated with DMSO. The arrow points to the cyst. (F) shows a morphant treated with TSA. Insets show kidney cyst in F or the lack of cyst in G. (H) Average of percentage of embryos with kidney cysts from 3 independent experiments. Twenty-five to fifty embryos were examined in each experiment. ***, P < 0.005.

Since TSA was identified in our screen for its ability to reverse dorsal curvature of pkd2/hi4166 mutants to ventral curvature, we further tested whether it can correct the body curvature phenotype of pkd2/hi4166 mutants by modifying dosage and the developmental stage when it is applied. Indeed, treatment of 200 nM TSA from 27 hpf could lead to a modest suppression: mutant embryos still curved dorsally but to a lesser degree (Fig. S2A). To quantify the severity of the curvature, we measured the tail curvature angle relative to body axis. Specifically, we imaged fish in side views, drew two lines connecting the tip of the yolk extension with the eye and the tip of the tail (Fig. 1C). We define the angle between these two lines as curvature angle. These measurements showed that TSA treatment was able to suppress the body curvature phenotype of pkd2/hi4166 significantly (Fig. 1E). When treated with 500 nM TSA from 27 hpf, all embryos from a pkd2/hi4166 heterozygous cross displayed straight body axis (Fig. 1 C and D), indicating that at this dosage and developmental stage, TSA has no effect on the body axis of wild-type embryos (hi4166+/+ and hi4166±), while specifically inhibit the curvature phenotype in mutant embryos. Thus, TSA applied at proper dosage and developmental stage can fully suppress the body curvature phenotype of pkd2/hi4166 mutant embryos.

TSA Suppresses Kidney Cyst Formation in pkd2 Morphants.

Since our screen relies on LR asymmetry and body curvature phenotypes as the readout, we tested the ability of the isolated compounds to also modulate kidney cyst formation in zebrafish PKD models. Since pkd2/hi4166 mutants do not display an obvious kidney cyst phenotype, presumably masked by maternal contribution of the pkd2 transcript (7), we used pkd2 morphants in this assay. One concern with evaluating cyst inhibition in developing embryos is that developmental delay may reduce cyst formation nonspecifically. Indeed, when we treated pkd2 morphants with 50 μM γ-secretase inhibitor VI, a compound we selected randomly, the embryos were necrotic, much smaller and more importantly, the percentage of cysts also decreased. To avoid this issue, we titrated the concentration of TSA carefully. When applied at 100 nM, the treated embryos showed no obvious morphological difference from vehicle treated embryos (Fig. 1 F and G). However, the percentage of cyst formation was decreased significantly: while 56.3 ± 2.9% of the pkd2 morphants injected with 0.5 mM pkd2 morpholino and treated with vehicle developed cysts, in TSA-treated morphants, the percentage of cyst formation decreased to 6.0 ± 2.8% (P < 0.005) (Fig. 1 F–H).

VPA, An Inhibitor for Class I HDACs, Can Suppress pkd2 Phenotypes in Zebrafish.

To verify that the TSA effect we observed is through the specific inhibition of HDACs, we next treated embryos with VPA, a compound that inhibits class I HDACs, but is structurally unrelated to TSA. When applied to wild-type embryos, VPA showed a similar effect as TSA. Specifically, when treated with 10–50 μM VPA from the 30% epiboly stage, embryos showed an increasingly severe body curvature phenotype (Fig. S3A), while embryos treated with 50 μM VPA from the later 20 somite stage showed only a slight ventral curvature phenotype (Fig. 2 A and B). VPM (dipropylacetamide), a chemical that is structurally similar to VPA but has no activity toward HDACs (13), had no effect even at 50 μM (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3B), suggesting that the observed effect of TSA and VPA was indeed due to inhibition of HDACs.

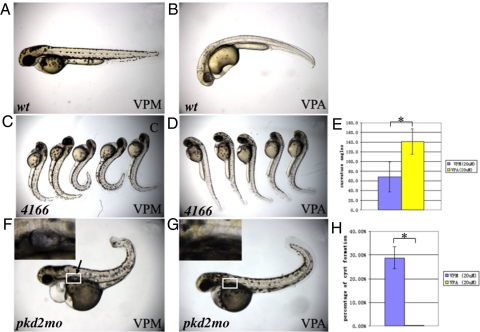

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of Class I HDACs can suppress the phenotypes of pkd2 mutants/morphants. (A and B) Treatment of 20 μm VPA from the shield stage leads to slight ventral curvature (B) on 2 dpf in wild-type embryos (wt) as compared to embryos treated with DMSO (A). (C–E) VPA can suppress the body curvature of pkd2/hi4166 mutant embryos. (C) shows mutant embryos treated with DMSO on 2 dpf. (D) shows mutant embryos treated with 20 μm VPA from 27 hpf on 2 dpf. (E) Average curvature angle in embryos treated with 20 μm VPM and 20 μm VPA. n = 5, *, P < 0.005, (F–H) Inhibition of kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants (pkd2mo) on 3 dpf by treatment of 20 μm VPA from the 20-somite stage. (F) shows a pkd2 morphants treated with 20 μm VPM. The arrow points to the cyst. (G) shows a morphant treated with VPA. White box: area shown in Insets. Insets show kidney cyst in F or the lack of cyst in G. (H) Average of percentage of embryos with kidney cysts from three independent experiments. Twenty-five to one hundred embryos were examined in each experiment. *, P < 0.005. 4166: embryos from pkd2/hi4166 heterozygous cross.

We next tested whether VPA, like TSA, could suppress the body curvature phenotype of pkd2 mutants. pkd2/hi4166 mutants treated with 20 μM VPA from the 20-somite stage showed an increased average curvature angle from 68° observed in vehicle treated embryos to 141°. This difference is statistically significantly (Fig. 2 C–E) and suggests that VPA may mimic TSA treatment in pkd2 mutants.

Finally, we tested whether VPA treatment is also capable of inhibiting kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants. pkd2 morphants treated with 20 μM VPA from the 20-somite stage did not exhibit a significant suppression of body curvature (Fig. 2G). Nonetheless, we observed a complete inhibition of kidney cyst formation. Specifically, while 29% vehicle treated morphants showed kidney cyst formation, 0% of embryos treated with VPA developed kidney cysts (Fig. 2 F–H).

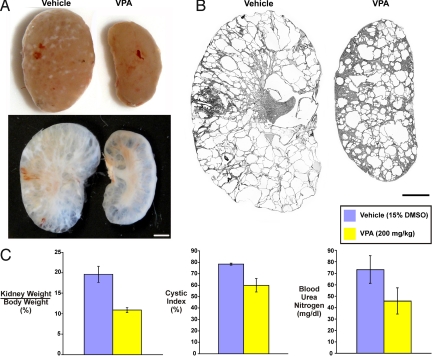

VPA Treatment Slows Cyst Progression in a Mouse Pkd1 Mutant.

We next asked whether class I HDAC inhibitors may be effective in treatment of polycystic kidney disease in mammalian systems. In performing this study, we sought to address two questions: the first is whether VPA can slow cyst growth in a mouse model of polycystic kidney disease and the second is whether this finding is extensible beyond polycystic disease due to mutations in Pkd2. We used a mouse model, Pkd1flox/flox;Pkhd1-Cre (41, 42), based on the mouse ortholog of PKD1, the human gene responsible for the most common and most severe form of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). The kidney selective Pkhd1-Cre is expressed primarily in the collecting ducts of the nephron. Pkd1flox/flox;Pkhd1-Cre mice have minimal kidney cysts around P10 but then rapidly develop massive cystic disease over the subsequent 2 weeks and have average survival to ≈7 weeks before succumbing to progressive kidney failure. Pkd1flox/flox;Pkhd1-Cre mice received either vehicle alone or VPA at 200 mg/kg for 14 days beginning at P10 and were killed at P25. Kidney size as assessed by kidney weight and kidney weight to body weight ratio (Fig. 3 A and C and Fig. S5 A–C) were significantly reduced in the VPA treated mice, while the body weight was not affected. The percentage of cystic area relative to total kidney area in histological sections, reported as a cystic index, also showed significant decrease in the VPA treated kidneys (Fig. 3 B and C and Fig. S5 A and B). Finally, reduction in cystic burden correlated with improved kidney function as measure by blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (Fig. 3C). Overall, these data support the conclusion that inhibition of class I HDAC with VPA slows the rate of cyst growth and the rate of decline in kidney function in ADPKD models based on mutation to Pkd1 and further validates the used of pkd2-based body curvature and and laterality phenotypes in zebrafish for therapeutic discovery in ADPKD.

Fig. 3.

VPA reduces cyst growth and improves kidney function in mouse models of polycystic kidney disease based on Pkd1. (A) Gross (Top) and cut surface (Bottom) appearance of vehicle and VPA (200 mg/kg) treated Pkd1flox/flox;Pkhd1-Cre mouse kidneys at P25 showing reduced kidney size in the VPA treated mice. (B) Representative scans using the image splicing feature of MetaMorph software applied to sagittal sections from vehicle and VPA treated kidneys. Images of one section from the other seven mice studied are provided in Fig. S5. (C) Aggregate data from vehicle treated (n = 5 mice, 10 kidneys) and VPA treated (n = 4 mice, 8 kidneys) mice showing significant differences in kidney weight-to-body weight ratio (P < 0.01), cystic index (P < 0.001) and blood urea nitrogen (P < 0.001). Absolute kidney and body weights are presented in Fig. S5. (Scale bar, 2 mm.)

Knockdown of a Class I HDAC Gene, hdac1, Can Suppress pkd2 Phenotypes.

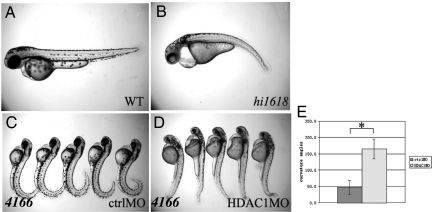

As a pan-HDAC inhibitor, TSA targets both class I and class II HDACs, while VPA is known to be more specific toward class I HDACs (12–14). Interestingly, wild-type zebrafish embryos treated with TSA or VPA showed very similar phenotypes: in addition to ventrally curved body axis, they also showed lighter pigmentation (23) (Figs. 1B and 2B and Fig. S4A), stunted pectoral fin formation (24) (Fig. S4A) and pericardiac edema (25) (Fig. S4 B–D). Notably, these phenotypes are reminiscent of those observed in hdac1/hi1618, an insertional mutant of hdac1 (25) (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S4B), which encodes a class I HDAC. To confirm this observation, we injected wild-type zebrafish embryos with a previously published morpholino oligo against hdac1 and observed similar phenotypes (26). On the other hand, a morpholino against hdac6, which encodes a class II HDAC, failed to produce such phenotypes. Together, these results suggest that inhibition of Class I HDACs, rather than other classes of HDACs, accounts for the majority of the observed effects of TSA and VPA treatment.

Fig. 4.

Depletion of hdac1 can suppress the phenotypes of pkd2 mutants. (A and B) Phenotypes of hdac1/hi1618 mutants on 2 dpf in side views. (A) shows a wild-type (WT) sibling, while (B) shows a mutant embryo (hi1618). (C–E) Injection of hdac1 morpholino can suppress body curvature of pkd2/hi4166 mutants on 2 pdf. (C) shows mutant embryos injected with the five base-pair mismatch control oligo. (D) shows mutant embryos injected with the hdac1 morpholino. (E) shows average curvature angle in embryos injected with control or hdac1 morpholino. n = 5, *, P < 0.05. (F–H) Injection of hdac1 morpholino can suppress kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants (pkd2mo) on 3 pdf. 4166: embryos from pkd2/hi4166 heterozygous cross; ctrolMO: embryos injected with control morpholino. HDAC1 MO: embryos injected with hdac1 morpholino.

We next tested whether direct knockdown of endogenous hdac1 could suppress the body curvature in pkd2 mutants. Indeed, injection of hdac1 antisense morpholino significantly suppressed the body curvature phenotype of pkd2/hi4166 mutants (curvature angle increased from 50 to 165°, n = 5, P < 10−4) (Fig. 4 C–E). Thus, suppression by TSA and VPA of pkd2 inactivation-associated body axis defects is likely mediated mainly through class I HDACs, particularly hdac1.

Automated Evaluation of the Body Curvature Phenotype.

In the above pilot visual screen, we used the laterality and body curvature as screen readout and identified HDAC inhibitors TSA and VPA as potent suppressors of pkd2 mutant phenotypes in fish and polycystic kidney disease in mice. Both these HDAC inhibitors can inhibit kidney cyst formation in pkd2 morphants and VPA can slow kidney cyst progression in a mouse Pkd1 mutant, supporting the validity of using these morphological features, especially the body curvature phenotype as an effective first filter to enrich hits for modifiers of kidney cyst formation.

The easily recognizable body curvature phenotype should allow automated classification and scoring in a high-throughput genetic or chemical screen. To probe such feasibility, we developed a computer algorithm that can classify and count body curvature automatically. In brief, we used a classifier that can detect and identify a small number of objects among a large number of images with modest computational resources (27). We trained this classifier to recognize zebrafish body axis by hand labeling a small set of fish images. The trained classifier can then classify and compute body curvature in three steps automatically: (i) fish identification, (ii) classification of head versus tail, (iii) curvature computation. We used this algorithm to classify 492 zebrafish embryos in low-resolution group pictures in random orientations and then compared the results with that from manual inspections (Fig. S6 A–D). The results from this classifier was satisfying, with an error rate of 2.2%, and suggest that this may be a powerful tool for quantifying screen results from large-scale zebrafish phenotype assays.

Discussion

In this study, we screened for compounds that can modify body axis curvature and laterality of zebrafish embryos. In previous compound screens carried out in zebrafish, thousands of compounds were screened using a preset concentration (28, 29). In this study, we opted to focus our effort on compounds with potent and specific activities and performed multiple rounds of screening to optimize dosage for each compound experimentally. As a result, the number of screened compounds is limited and hit rate from this screen may not be applicable to other screens.

As a model system, zebrafish has many advantages. However, cyst formation in zebrafish is not particularly suitable for compound screens. First, zebrafish pkd2 mutant does not develop kidney cyst. Although pkd2 morphants do develop cyst, morphant phenotypes are noisier than that in mutants and requires larger sample size and careful statistical analysis to appreciate a difference. Second, it is possible to inhibit cyst formation by grossly delaying development, necessitating careful titration of each compound. These shortcomings make it necessary to design surrogate assays and to validate hits in a more suitable system, such as conditional mouse knockout models.

Previous studies showed a close association between the body curvature phenotype and cyst formation. We therefore hypothesized that the body curvature phenotype could be used as a straightforward surrogate marker for the cystic kidney phenotype in an initial round of screening. The second phenotype we scored for was the laterality of the body plan. We reasoned that since the cilium plays a critical role in both laterality and cyst formation, hits affecting LR asymmetry would likely be involved in PKD as well. Our results validated this approach. First, three out of the six positives for the body curvature phenotype also affect laterality, supporting close associations between these two phenotypes. Second and more critically, we were able to show that VPA, a compound we reached through the screen in zebrafish, can inhibit cyst formation and improve kidney function in a mouse PKD model. Since body curvature is an easy to score morphological phenotype, we developed a computer program that could automatically quantify this phenotype, making it feasible to carry out large-scale first pass screens using this particular feature.

From this screen, we identified HDAC inhibitors as suppressors of zebrafish PKD models. The result that TSA and VPA, two HDAC inhibitors of different structure classes, are both able to suppress pkd2 mutant phenotypes demonstrates the specificity of the compounds' effect. The finding that inactivation of hdac1 also has similar suppression effect on pkd2 mutants provides further genetic support to the above conclusion. We further tested the validity of the compound screen by evaluating the effects of VPA on a mouse model of polycystic kidney disease based on conditional inactivation of Pkd1. We demonstrated that treatment with VPA resulted in both structural and functional improvement of polycystic kidney disease in this model. The beneficial effects in a mammalian model further support the validity of compound library screening using the body curvature and left-right axis phenotypes in zebrafish. It is noteworthy that we used a Pkd1 mouse model rather than a Pkd2 mouse model in the in vivo testing. The observed efficacy in this model shows that the compound library screen using pkd2 mutant fish can successfully identify compounds that target the polycystic disease pathway in general and is not confined solely to Pkd2-dependent phenotypes.

HDACs have not been previously linked to kidney cyst formation. However, overexpression of HDACs has been reported in multiple tumor types (30, 31). Conversely, treatment of HDAC inhibitors can suppress cell proliferation and induce differentiation. In the meantime, PKD has been compared to benign tumors. In PKD, kidney cysts, which are connected with existing tubules and ducts early in their growth, have been found to be clonal and exhibit increased cell proliferation rate (32–34). Together, these observations are consistent with a critical role of HDACs in PKD pathogenesis.

One of the HDAC inhibitors that can suppress pkd2 mutants/morphants is VPA. Interestingly, VPA is most potent toward class I HDACs (HDAC1–3 and 8). Although it can inhibit Class II subclass I (HDACs 4, 5, 7, and 9) at higher concentrations, it has no activity toward class II subclass II of HDACs (HDACs 6 and 10) (12). Consistently, both hdac1 mutants and morphants displayed similar phenotypes as embryos treated with TSA and VPA, while knockdown of hdac6 failed to do so. Notably, in addition to histone modification, HDAC6 can deacetylate tubulin (35–37). Our results thus suggest that inhibition of class I HDACs, especially hdac1 activity, but not tubulin deacetylation, is likely to be mainly responsible for the suppression of pkd2 phenotypes. The mechanism underlying the cyst inhibition activity of HDAC inhibitors is currently unclear. Cilia are still able to form in hdac1 mutants. We therefore favor a model in which ciliary signal regulates the transcription downstream targets through chromatin remodeling.

HDAC inhibitors are being intensively developed as anti-cancer drugs. Multiple HDAC inhibitors have either been approved by FDA, or are at different stages of clinical trials (30, 38, 39). Several of these inhibitors may be used as candidate drugs for PKD treatment. Excitingly, VPA is an established medicine for treating seizure and bipolar disorder and is known to be well tolerated by patients (12). Currently, VPA is being evaluated in clinical trials for its potential anti-tumor activity (12). Our results suggest that in addition to cancer treatment, VPA and other drugs that target HDACs may be promising candidates for PKD treatment.

Experimental Protocol

Zebrafish Care.

zebrafish were raised according to standard protocol (40). All of the lines were obtained from Nancy Hopkins' laboratory and the Zebrafish International Resource Center and are maintained by crossing to TAB wild-type fish.

Screen for Modifiers of the pkd2 and ift172 Mutant.

Compounds were purchased from Sigma, Calbiochem, Biomol, and Cayman Chemical. A complete list is available up request. Embryos were arrayed onto 12-well plates with 25 embryos per well. At the 50% epiboly stage, chemicals were added with 1% DMSO. Embryos in 1% DMSO were used as controls. Phenotypes, including LR asymmetry and body curvature, were scored at 30 hpf, 2 dpf, and 5 dpf. LR asymmetry was determined by examining the heart position at 30 hpf. Positive hits, which changed the LR asymmetry or body curvature in either pkd2/hi4166 or ift172/hi2211 mutant, were further tested in wild-type embryos.

Morpholino Injection.

Morpholino oligos were purchased from Genetools and injected into embryos at one- to two-cell stage. Oligos were injected at the following amounts: 1–2 ng morpholino oligo against pkd2 (5′-AGGACGAACGCGACTGGAGCTCATC-3′, as described in ref. 7), 0.1 ng hdac1 morpholino oligo (5′-TTGTTCCTTGAGAACTCAGCGCCAT-3′, as described in ref. 26), and five-base mismatch control morpholino oligo for hdac1 (5′-TTcTTgCTTGAcAACTCAGgGCgAT-3′, as described in ref. 26).

Mouse Models and Treatment.

The Pkd1flox and Pkhd1-Cre mice been reported in refs. 41 and 42. Pkd1flox/+;Pkhd1-Cre mice were intercrossed with Pkd1flox/flox and litters were genotyped at P7. Pkd1flox/flox;Pkhd1-Cre progeny were used in either the treatment group or the vehicle control group dosed once a day for 14 days beginning at P10. The treatment group received 200 mg/kg of valproic acid (VPA) in 15% DMSO/85% saline by intraperitoneal injection while the vehicle group received the same volume of 15% DMSO/85% saline without VPA. A total of nine mice (four VPA and five vehicle) were studied. Mice were killed at P25. Kidneys were sectioned in the sagittal plane near the midline and one H&E section from each kidney was scanned using the image splicing feature of the MetaMorph v.7.1 acquisition software (Universal Imaging) and a motorized microscope stage. Cystic and noncystic areas were determined using integrated morphometry feature of MetaMorph and the cystic index reported as the percentage of total area occupied by cysts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Martina Brueckner and Shiaulou Yuan for critical reading of this manuscript and members of the Sun laboratory for helpful discussions and Peter Igarashi and the UTSW O'Brien Kidney Center (National Institutes of Health P30DK079328) for the Pkhd1-Cre mice. This work was supported by the Mallinckrodt Foundation (Z.S.), National Institutes of Health Grants DK069528 (to Z.S.), DK54053 and DK57328 (to S.S.), and Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization Grant W911NF0810020 (to P.E.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0911987106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gabow P, Grantham J. In: Diseases of the Kidney. Schrier R, Gottschalk C, editors. Boston: Little Brown and Co.; 1997. pp. 521–560. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consortium TEPKD. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16. Cell. 1994;77:881–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mochizuki T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pazour GJ, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport and cilia-dependent diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:551–555. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pazour GJ, Witman GB. The vertebrate primary cilium is a sensory organelle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:813–825. doi: 10.1038/nrm952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Z, et al. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies cilia genes as a principal cause of cystic kidney. Development. 2004;131:4085–4093. doi: 10.1242/dev.01240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Z, Hopkins N. vhnf1, the MODY5 and familial GCKD-associated gene, regulates regional specification of the zebrafish gut, pronephros, and hindbrain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3217–3229. doi: 10.1101/gad946701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ. Kupffer's vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development. 2005;132:1247–1260. doi: 10.1242/dev.01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer-Zucker AG, et al. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer's vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:1907–1921. doi: 10.1242/dev.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond IA, et al. Early development of the zebrafish pronephros and analysis of mutations affecting pronephric function. Development. 1998;125:4655–4667. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duenas-Gonzalez A, et al. Valproic acid as epigenetic cancer drug: Preclinical, clinical and transcriptional effects on solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:206–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farooq M, et al. Histone deacetylase 3 (hdac3) is specifically required for liver development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;317:336–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phiel CJ, et al. Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36734–36741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitman M, Mercola M. TGF-beta superfamily signaling and left-right asymmetry. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.64.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennekamp P, et al. The ion channel polycystin-2 is required for left-right axis determination in mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12:938–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami M, Nakanishi N. The role of an endogenous PKA inhibitor, PKIalpha, in organizing left-right axis formation. Development. 2001;128:2509–2515. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nonaka S, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Hamada H. Determination of left-right patterning of the mouse embryo by artificial nodal flow. Nature. 2002;418:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature00849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nonaka S, et al. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell. 1998;95:829–837. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo DD, Miao SY, Pelayo JC, Woolf AS. Taxol inhibits progression of congenital polycystic kidney disease. Nature. 1994;368:750–753. doi: 10.1038/368750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida M, Kijima M, Akita M, Beppu T. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17174–17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ignatius MS, Moose HE, El-Hodiri HM, Henion PD. colgate/hdac1 Repression of foxd3 expression is required to permit mitfa-dependent melanogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:568–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pillai R, Coverdale LE, Dubey G, Martin CC. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC-1) required for the normal formation of craniofacial cartilage and pectoral fins of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:647–654. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunliffe VT. Histone deacetylase 1 is required to repress Notch target gene expression during zebrafish neurogenesis and to maintain the production of motoneurones in response to hedgehog signalling. Development. 2004;131:2983–2995. doi: 10.1242/dev.01166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi M, et al. Histone deacetylase 1 regulates retinal neurogenesis in zebrafish by suppressing Wnt and Notch signaling pathways. Development. 2005;132:3027–3043. doi: 10.1242/dev.01881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbano P, Coifman R. Compressive Mahalanobis classifiers. Proceedings of the Conference of Machine Learning and Signal Processing. IEEE. 2008:345–349. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitambi SS, McCulloch KJ, Peterson RT, Malicki JJ. Small molecule screen for compounds that affect vascular development in the zebrafish retina. Mech Dev. 2009;126:464–477. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterson RT, et al. Chemical suppression of a genetic mutation in a zebrafish model of aortic coarctation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bieliauskas AV, Pflum MK. Isoform-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1402–1413. doi: 10.1039/b703830p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehnert JM, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Biology and mechanism of action. Cancer J. 2007;13:23–29. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31803c72ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanoix J, D'Agati V, Szabolcs M, Trudel M. Dysregulation of cellular proliferation and apoptosis mediates human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) Oncogene. 1996;13:1153–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadasdy T, et al. Proliferative activity of cyst epithelium in human renal cystic diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:1462–1468. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V571462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian F, Watnick TJ, Onuchic LF, Germino GG. The molecular basis of focal cyst formation in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type I. Cell. 1996;87:979–987. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubbert C, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–458. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuyama A, et al. In vivo destabilization of dynamic microtubules by HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:6820–6831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, et al. HDAC-6 interacts with and deacetylates tubulin and microtubules in vivo. EMBO J. 2003;22:1168–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallinari P, Di Marco S, Jones P, Pallaoro M, Steinkuhler C. HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: From molecular biology to cancer therapeutics. Cell Res. 2007;17:195–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Deacetylase enzymes: Biological functions and the use of small-molecule inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2002;9:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 4th Ed. Eugene: Univ. of Oregon Press; 2000. pp. 1.1–3.26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel V, et al. Acute kidney injury and aberrant planar cell polarity induce cyst formation in mice lacking renal cilia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1578–1590. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shibazaki S, et al. Cyst formation and activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway after kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1505–1516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.