Abstract

Purpose

There is still debate about the timing of revascularization in patients with acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). We analyzed the long-term clinical outcomes of the timing of revascularization in patients with acute NSTEMI obtained from the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR).

Materials and Methods

2,845 patients with acute NSTEMI (65.6 ± 12.5 years, 1,836 males) who were enrolled in KAMIR were included in the present study. The therapeutic strategy of NSTEMI was categorized into early invasive (within 48 hours, 65.8 ± 12.6 years, 856 males) and late invasive treatment (65.3 ± 12.1 years, 979 males). The initial- and long-term clinical outcomes were compared between two groups according to the level of Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score.

Results

There were significant differences in-hospital mortality and the incidence of major adverse cardiac events during one-year clinical follow-up between two groups (2.1% vs. 4.8%, p < 0.001, 10.0% vs. 13.5%, p = 0.004, respectively). According to the TIMI risk score, there was no significant difference of long-term clinical outcomes in patients with low to moderate TIMI risk score, but significant difference in patients with high TIMI risk score (≥ 5 points).

Conclusions

The old age, high Killip class, low ejection fraction, high TIMI risk score, and late invasive treatment strategy are the independent predictors for the long-term clinical outcomes in patients with NSTEMI.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, non-ST-segment elevation, invasive treatment, TIMI risk score, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

The recent guidelines of the American College of Cardiology-American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommended an early invasive approach for the high-risk patients who suffer from acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation.1-4 Despite these recommendations, it is not clear whether an early invasive strategy reduces mortality in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients. Recent Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable Coronary Syndromes (ICTUS) trial did not show superiority of an early invasive strategy for NSTEMI patients at the 1-year and 4-year clinical follow-up.5,6 However, such recent advances in medical therapy as the early use of clopidogrel and intensive lipid-lowering therapy have been shown to improve the prognosis for patients suffering from acute coronary syndrome.7,8

Therefore, we undertook the present study to analyze the clinical efficacy of the timing of revascularization and to test the hypothesis that an early invasive strategy is superior to a late invasive strategy for treating the NSTEMI patients who are registered in the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR). We compared two large patient cohorts obtained from the 50 multi-center KAMIR; one consisting of consecutive acute myocardial infarction patients treated with early invasive strategy and the other patients treated with late invasive strategy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients population and study design

The KAMIR is a prospective, multi-center, observational registry designed to examine current epidemiology, inhospital management, and outcome of patients with acute MI in Korea for the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Korean Circulation Society.9,10 Fifty high volume university, community centers with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) facilities and on-site cardiac surgery comprise the KAMIR. 2,845 patients (65.6 ± 12.5 years, 1,836 males) who were followed-up for one-year were included in the present study. Eligible patients for this study were required to have all three of the following: 1) symptoms of ischemia increasing or occurring at rest, 2) an elevated cardiac troponin I level (≥ 2.0 ng/mL) or CKMB (19 U/L, exceeding twice the upper limit of normal), and 3) ischemic changes assessed by electrocardiography, defined as ST-segment elevation, depression, or T-wave inversion of ≥ 0.2 mV in two contiguous leads.

We analyzed baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, relevant laboratory results, and pharmacotherapy. And we calculated Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score11 of each patients at admission to Emergency Department. Echocardiography was performed in all patients before discharge. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at the six-month and one-year clinical follow-up were evaluated and were defined as the composite of 1) all cause death, 2) non-fatal MI, and 3) re-PCI or coronary artery bypass graft. Re-infarction was defined as the recurrence of symptoms or electrocardiographic changes in association with a rise in cardiac enzymes above the normal upper limit. All data were recorded on a standardized, electronic, web-based registry at http://www.kamir.or.kr.

Pre and post-intervention management

Prior to the index intervention, all patients received 300 mg of aspirin and 450 to 600 mg of clopidogrel. After the procedure, patients were maintained on aspirin 100-200 mg indefinitely. Clopidogrel 75 mg per day was prescribed for a minimum of 4 weeks in patients treated with bare metal stent (BMS) and for a minimum of 6 months in patients treated with drug-eluting stent (DES). The duration of clopidogrel therapy and triple anti-platelet therapy, including cilostazol, after the procedure was left to the discretion of the operator and referring physicians.

Treatment strategy

The patients who were assigned to the early invasive strategy group (Group I: 65.8 ± 12.6 years, 856 males) were scheduled to undergo angiography within 48 hours after hospitalization and then PCI was performed when appropriate; the decision to perform PCI was based on the coronary anatomy. The patients who were assigned to the late invasive strategy group (Group II: 65.3 ± 12.1 years, 979 males) were treated medically first. These patients were scheduled to undergo angiography and subsequent revascularization only if they had refractory angina despite optimal medical treatment or they had hemodynamic or rhythmic instability.

Statistical analysis

We compared the in-hospital mortality, the admission duration of coronary care unit, and the incidence of MACE during one-year clinical follow-up between two groups. The subgroup analysis was done according to each TIMI risk score and several baseline clinical features including age, gender, the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus, the presence or absence of ST-segment deviation, or the level of glomerular filtration rate. And the predictive factors for MACE at one-year clinical follow-up were calculated by multiple logistic regression analysis.

The statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 15.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses. Continuous variables with normal distributions were expressed as mean ± SD and they were compared with the use of an unpaired Student's t-test. Categorical variables were compared with the use of the chi-square test, where appropriate. The relative risks were calculated by dividing the Kaplan-Meier estimated rate of an event in the early invasive strategy group by that of the late invasive strategy group. The 95 percent confidence interval for the relative risk was calculated with the use of the standard errors from the Kaplan-Meier curve. A p less than 0.05 was deemed as significant. We performed a propensity score analysis to adjust for imbalances in baseline characteristics between early invasive group and late invasive group. We used logistic regression model to derive a propensity score for early invasive strategy that included 63 variables.

RESULTS

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study population

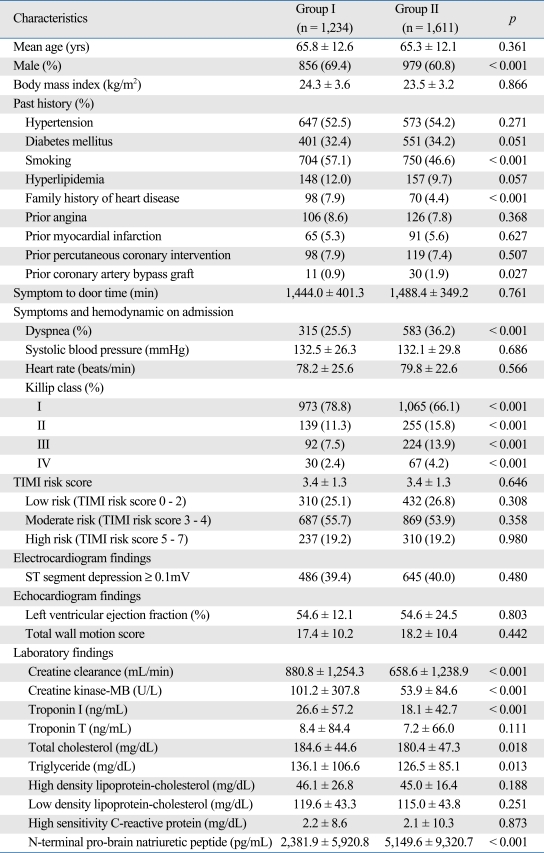

Among the 2,845 patients with NSTEMI who were followed-up during one-year there were 1,234 early invasive treatment strategy patients and 1,611 late invasive strategy patients. The baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics and Hemodynamics

TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction.

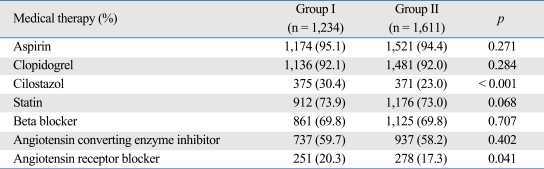

Medical therapy during hospitalization

For medical therapy at discharge, significant differences in the proportions of patients receiving particular drugs were observed. Cilostazol and angiotensin receptor blocker were more frequently used in group I, as shown in Table 2. And other medications at discharge are also shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Medical Therapy at Discharge

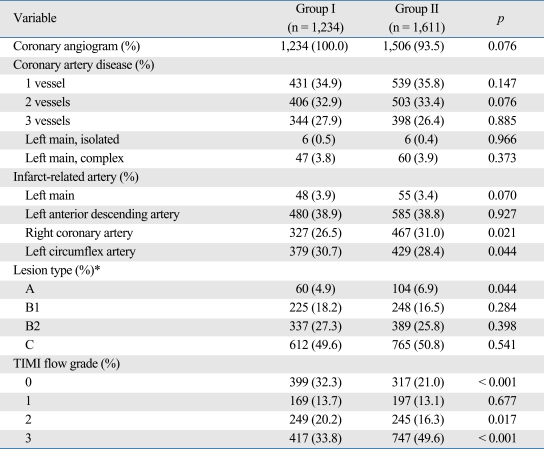

Coronary angiographic findings

In the early invasive strategy group, coronary angiography was done in 100% of patients during hospitalization, compared with 93.5% in the late invasive strategy group. The baseline coronary angiographic characteristics are shown in Table 3. Approximately 65% of the patients had multi-vessel diseases. The most common infarct-related artery was the left anterior descending artery in both groups. A lesion type B2 or C, according to the ACC/AHA classification, was present in 76.9% of group I patients and 76.6% of group II patients. A TIMI flow grade 2 or 3 was observed in 54.0% of group I patients and 65.9% of group II patients.

Table 3.

Baseline Coronary Angiographic Variables

TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction.

*Lesion type according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification.

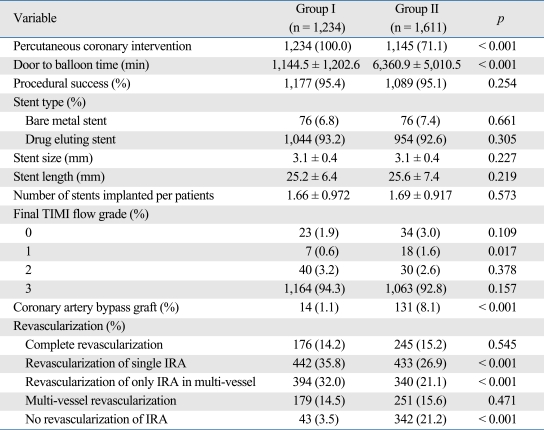

Procedural characteristics

As shown in Table 4, PCI was tried in 100% of patients in group I, during hospitalization. The mean door to balloon time was 1,144 ± 1,202 minutes. PCI was done successfully in 95.4% patients. Coronary bypass graft surgery was done in 1.1% during hospitalization. Total revasculariza-tion rate was 96.5%. In group II, PCI was tried in 71.7% of the patients during hospitalization. The mean door to balloon time was 6,360 ± 5,010 minutes (vs. group I, p < 0.001). The success rate was 95.1%. Coronary bypass graft surgery was done in 8.1% (vs. group I, p < 0.001) during hospitalization. Total revascularization rate was 78.8% (vs. group I, p < 0.001). The average diameter, length, and number of stent were not significantly different between two groups.

Table 4.

Procedural Characteristics

TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction; IRA, infarct related artery.

In hospital outcomes according to TIMI risk score

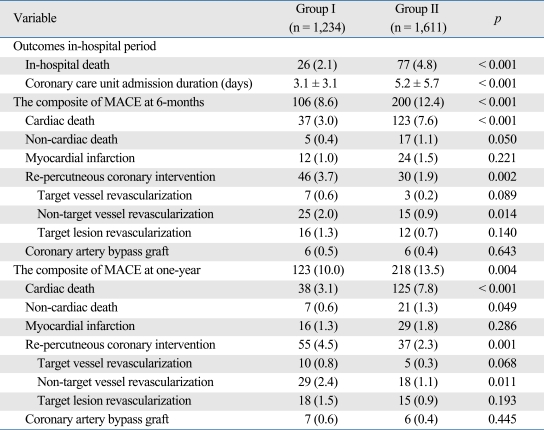

The estimated in-hospital mortality was 2.1% in group I and 4.8% in group II (relative risk: 2.36, 95% confidence interval: 1.51 to 3.71; p < 0.001) (Table 5). The patients in both groups were classified into 3 sub-groups according to the TIMI risk score: 742 patients (310 patients of group I and 432 patients of group II) had a TIMI risk score of 0-2 points (the low risk group), 1,556 patients (687 patients of group I and 869 patients of group II) had a TIMI risk score of 3-4 points (the moderate risk group) and 547 patients (237 patients of group I and 310 patients of group II) had a TIMI risk score of 5-7 points (the high risk group). For the low and moderate and high risk patients, no significant differences of the in-hospital mortality (p = 0.872, p = 0.052, respectively) were observed between two groups. However, for the high risk patients, there was a significantly lower in-hospital mortality in group I (3.3% vs. 8.9%, respectively, p < 0.001). And the duration of admission to the coronary care unit was significantly longer in group II (3.1 vs. 5.2 days, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes during One-Year Follow-Up

MACE, major adverse cardiac event.

MACE at six-months and one-year according to TIMI risk score

The incidence of MACE was 10.0% in group I and 13.5% in group II (p = 0.004) at one-year clinical follow-up. The composite of MACE is described in Table 5. The rate of cardiac death was higher in group II during six-months and one-year clinical follow-up (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 respectively). However, the rate of re-PCI (especially, the rate of revascularization of non-target vessel) was higher in group I (p = 0.002 at six-months, p = 0.001 at one-year).

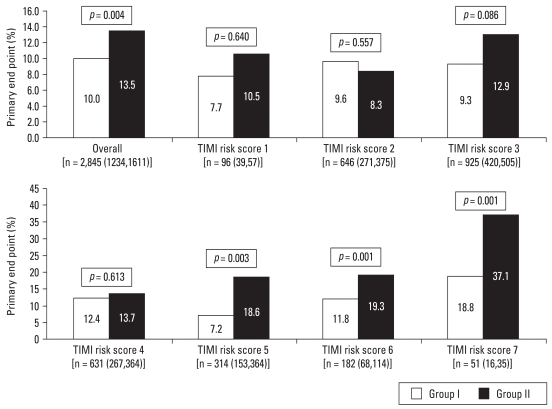

In the subgroup analysis according to each TIMI risk score, there was no significant difference in the incidence of MACE during one-year clinical follow-up in patients with TIMI risk score between 1 and 4. However, incidence of MACE was significantly lower in patients of group I with TIMI risk score between 5 and 7 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Primary end point (one-year major adverse cardiac events) according to the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score.

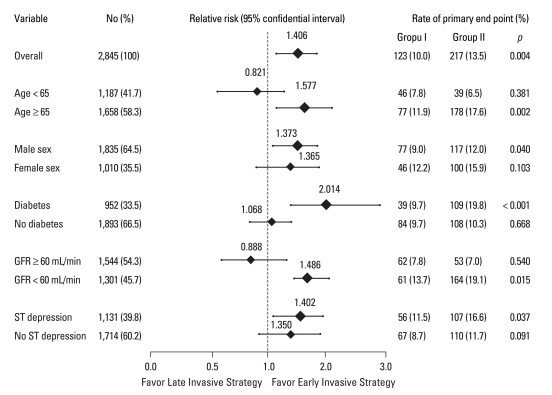

Subgroup analysis according to age, gender, diabetes, renal function, and ST segment depression

For patients with old age (over 65 years), male, diabetes mellitus, lower GFR (below 60 mL/min), and the presence of ST segment depression, the incidence of MACE was lower in group I (relative risk: 1.577, 1.373, 2.014, 1.486, 1.402, p = 0.002, 0.040, < 0.001, 0.015, 0.037, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Estimated rates and relative risk of the composite primary end points of death from cardiac or non cardiac causes, recurrent myocardial infarction, target vessel or non-target vessel or target lesion revascularization at one year according to subgroups.

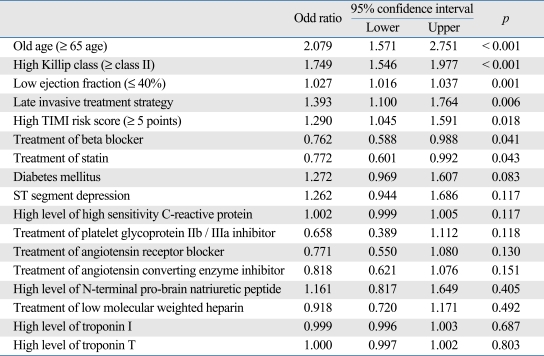

Multi-variate analysis of predictors of one-year MACE

Multivariate analysis was conducted by using the meaningful factors in univariate analysis and the other factors that have been reported to improve the prognosis of patients with acute MI. These factors included administration of angiotensin receptor blocker, statin, platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, and low molecular weight heparin.

The predictors for one-year MACE were found to be old age, a higher Killip class, a lower ejection fraction, a higher TIMI risk score, and late invasive treatment strategy (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multi-Variate Analysis for the Predictors of One-Year Major Adverse Cardiac Events

TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction

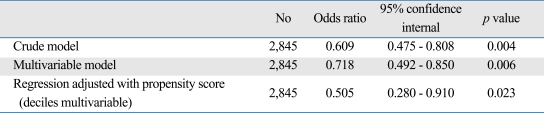

Early invasive strategy improved the one-year outcome in logistic regression model to derive a propensity score analysis (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of the Estimated Early Invasive Strategy of One Year Outcome Using Multivariable Logistic Regression, Regression Adjustment with the Propensity Score

DISCUSSION

Acute coronary syndrome has been categorized into unstable angina, NSTEMI, and STEMI.12 The most effective treatment for acute coronary syndrome is revascularization via performing PCI.13 Many clinical studies have been carried out to decide the optimal time for performing coronary intervention for NSTEMI patients. Our results demonstrated that an early invasive strategy is effective for reducing the long-term outcome in high-risk patients. The relative risks for long-term outcome in these patients were different according to age, gender, diabetes, ST-segment changes, and renal function. These findings were comparable to the previously reported clinical trials.9,14-17

In five large, randomized trials18-22 [Veterans Affairs Non-Q-Wave Infarction Strategies in Hospital (VANQWISH), Fragmin and Fast Revascularization during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease (FRISC) II, Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine the Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 18 (TACTICS-TIMI 18), TIMI IIIB and the Third Randomized Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-3)], a routine, early invasive strategy (early angiography followed by revascularization, depending on the angiographic findings) was compared with a "conservative" strategy (angiography and subsequent revascularization only if medical therapy failed or substantial residual ischemia was documented). An early invasive strategy was shown to be beneficial by the FRISC II, TACTICS-TIMI 18 and RITA-3 studies, especially in the subgroup of patients who were at a high risk, such as those patients presenting with an elevated cardiac troponin level. However, the most recent randomized ICTUS trial showed that an early invasive strategy was not superior to an early conservative strategy, even for the high risk patients, on the short-term and long-term clinical follow-up.5,6

Recent guidelines recommended an early invasive approach for the high-risk NSTEMI patients. In our study, an early invasive strategy was better than a late invasive strategy for patients with NSTEMI, especially for the high risk patients. We defined the high risk patient who had higher than 5 points of TIMI risk score and when early invasive strategy as door to balloon time was within 48 hours. Our present results were not in accordance with those of the previous trials owing to differences in the study design, particularly the risk profile of patients included and the definition of the end points. There are several possible explanations for the observed differences in outcome between the present study and the previous trials. First, the revascularization rate was higher in our study (96.5% for the early invasive strategy group and 78.8% for the late invasive strategy group during hospitalization) as compared with those in the ICTUS (76% vs. 40%, respectively), TIMI-IIIb (64% vs. 58%, respectively), VANQWISH (44% vs. 33%, respectively), FRISC II (77% vs. 37%, respectively), TACTICS-TIMI 18 (61% vs. 44%, respectively), and RITA-3 (57% vs. 28%, respectively). The patients in our study had higher cardiac troponin I levels (26.6 ng/mL in group I and 18.1 ng/mL in group II) as compared with those of other studies. Therefore, the patients who were enrolled in our study were generally at a higher risk. Second, myocardial damage that is related to the PCI is a disadvantage of early invasive treatment. The prognostic implications of peri-procedural myocardial damage are controversial.23,24 However, some reports suggested that the prognosis of patients with such injury should be regarded to be similar to that of patients with spontaneous necrosis. Long term follow-up is necessary to determine whether the increased incidence of procedure-related myocardial damage in the early invasive strategy group in our study eventually results in a worse prognosis.

This study has some limitations. First, our study is multicenter prospective registry study, and it is not randomized, and controlled. Therefore, there was probably a selection bias when enrolling patients in both groups. The level of cardiac enzymes was higher in group I patients than that in group II patients. The patients who complained of ongoing chest pain were more frequent in group I as compared with group II. High levels of cardiac enzymes25,26 and ongoing chest pain are representative markers of progressive myocardial ischemia. There was also a tendency for the doctors to perform early invasive treatment for patients with high levels of cardiac enzyme. Thus, the high risk patients could be included in group I. Second, the patients who underwent coronary bypass grafting were highly prevalent in group II. We thought that difficulty lesions were more common in group II. These findings might have affected the association of early invasive treatment with better clinical results. Finally, the duration of our study was relatively short. Our study is a comparison of the MACE at one-year. The ICTUS study had 4-years of follow-up data and the VANQWISH had 23-months of follow-up data. In conclusion, our findings suggested that an early invasive strategy could improve long-term outcome for the KAMIR patients with high risk (exceeding 5 points of TIMI risk score).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was performed with the support of The Korean Society of Circulation in the memorandum of the 50th Anniversary of The Korean Society of Circulation.

Korea Acute Myocardial infarction Registry (KAMIR) Study Group of Korean Circulation Society

Myung Ho Jeong, MD, Young Keun Ahn, MD, Shung Chull Chae, MD, Jong Hyun Kim, MD, Seung Ho Hur, MD, Young Jo Kim, MD, In Whan Seong, MD, Dong Hoon Choi, MD, Jei Keon Chae, MD, Taek Jong Hong, MD, Jae Young Rhew, MD, Doo Il Kim, MD, In Ho Chae, MD, Jung Han Yoon, MD, Bon Kwon Koo, MD, Byung Ok Kim, MD, Myoung Yong Lee, MD, Kee Sik Kim, MD, Jin Yong Hwang, MD, Myeong Chan Cho, MD, Seok Kyu Oh, MD, Nae Hee Lee, MD, Kyoung Tae Jeong, MD, Seung Jea Tahk, MD, Jang Ho Bae, MD, Seung Woon Rha, MD, Keum Soo Park, MD, Chong Jin Kim, MD, Kyoo Rok Han, MD, Tae Hoon Ahn, MD, Moo Hyun Kim, MD, Ki Bae Seung, MD, Wook Sung Chung, MD, Ju Young Yang, MD, Chong Yun Rhim, MD, Hyeon Cheol Gwon, MD, Seong Wook Park, MD, Young Youp Koh, MD, Seung Jae Joo, MD, Soo Joong Kim, MD, Dong Kyu Jin, MD, Jin Man Cho, MD, Byung Ok Kim, MD, Sang-Wook Kim, MD, Jeong Kyung Kim, MD, Tae Ik Kim, MD, Deug Young Nah, MD, Si Hoon Park, MD, Sang Hyun Lee, MD, Seung Uk Lee, MD, Hang-Jae Chung, MD, Jang Hyun Cho, MD, Seung Won Jin, MD, Yang Soo Jang, MD, Jeong Gwan Cho, MD, and Seung Jung Park, MD

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, Boersma E, Budaj A, Fernández-Avilés F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598–1660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction 2002: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina) Circulation. 2002;106:1893–1900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000037106.76139.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King SB, 3rd, Smith SC, Jr, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Jacobs AK, Morrison DA, Williams DO, et al. 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA/ SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008;117:261–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollack CV, Jr, Braunwald E. 2007 Update to the ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: implications for emergency department practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, Dunselman PH, Janus CL, Bendermacher PE, et al. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1095–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch A, Windhausen F, Tijssen JG, Verheugt FW, Cornel JH, de Winter RJ. Long-term outcome after an early invasive versus selective invasive treatment strategy in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome and elevated cardiac troponin T (the ICTUS trial): a follow-up study. Lancet. 2007;369:827–835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta RH, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Ohman EM, Cannon CP, Gibler WB, et al. Acute clopidogrel use and outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KH, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, et al. Gender differences of success rate of percutaneous coronary intervention and short term cardiac events in Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon TG, Bae JH, Jeong MH, Kim YJ, Hur SH, Seong IW, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is associated with adverse short-term clinical outcomes in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabatine MS, Antman EM. The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction risk score in unstable angina/non ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:89S–95S. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)03019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricoci P, Peterson ED, Roe MT. Patterns of guideline adherence and care delivery for patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:30Q–35Q. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denardo SJ, Davis KE, Tcheng JE. Effectiveness and safety of reduced-dose enoxaparin in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome followed by antiplatelet therapy alone for percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1376–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, Armstrong PW, Gibler WB, Rich MW, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: Non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2549–2569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones PH. Clinical significance of recent lipid trials on reducing risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:133B–140B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M, Chow CM, Fitchett DH, Georgescu AA, et al. ST-segment depression in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: quantitative analysis may not provide incremental prognostic value beyond comprehensive risk stratification. Am Heart J. 2006;152:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson CM, Dumaine RL, Gelfand EV, Murphy SA, Morrow DA, Wiviott SD, et al. Association of glomerular filtration rate on presentation with subsequent mortality in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; observations in 13,307 patients in five TIMI trials. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1998–2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI IIIB trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia. Circulation. 1994;89:1545–1556. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Crawford MH, Blaustein AS, Deedwania PC, Zoble RG, et al. Outcomes in patients with acute non-Q-wave myocardial infarction randomly assigned to an invasive as compared with a conservative anagement strategy. Veterans Affairs Non-Q-Wave Infarction Strategies in Hospital (VANQWISH) Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1785–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallentin L, Lagerqvist B, Husted S, Kontny F, Ståhle E, Swahn E. Outcome at 1 year after an invasive compared with a non-invasive strategy in unstable coronary-artery disease: the FRISC II invasive randomised trial. FRISC II Investigators. Fast Revascularisation during Instability in Coronary artery disease. Lancet. 2000;356:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Vicari R, Frey MJ, Lakkis N, et al. Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1879–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, Clayton TC, Chamberlain DA, Shaw TR, et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina. Lancet. 2002;360:743–751. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09894-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavallini C, Savonitto S, Violini R, Arraiz G, Plebani M, Olivari Z, et al. Impact of the elevation of biochemical markers of myocardial damage on long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the CK-MB and PCI study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1494–1498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roe MT, Mahaffey KW, Kilaru R, Alexander JH, Akkerhuis KM, Simoons ML, et al. Creatine kinase-MB elevation after percutaneous coronary intervention predicts adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westerhout CM, Fu Y, Lauer MS, James S, Armstrong PW, Al-Hattab E, et al. Short-and long-term risk stratification in acute coronary syndromes: the added value of quantitative ST-segment depression and multiple biomarkers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:939–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe AS, Babuin L, Apple FS. Biomarkers in acute cardiac disease: the present and the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]