Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease that is very rare in Asians: only a few cases have been reported in Korea. We treated a female infant with CF who had steatorrhea and failure to thrive. Her sweat chloride concentration was 102.0 mM/L. Genetic analysis identified two novel mutations including a splice site mutation (c.1766+2T>C) and a frameshift mutation (c.3908dupA; Asn1303LysfsX6). Pancreatic enzyme replacement and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation enabled the patient to get a catch-up growth. This is the first report of a Korean patient with CF demonstrating pancreatic insufficiency. CF should therefore be considered in the differential diagnosis of infants with steatorrhea and failure to thrive.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, Cystic Fibrosis Conductance Regulator, Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency, Mutation

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease affecting the respiratory, digestive, endocrine, and reproductive systems. Although it primarily affects the lungs, disturbances in the gastrointestinal system is also critical for the management of the disease. Management of pancreatic insufficiency is needed to extend life expectancy and to maintain a good quality of life (1, 2). The incidence of CF in Caucasian populations is about one in 2,500 newborns (3). However, the disease is very rare in Asian populations. The reported incidence is one in 90,000 Asian infants in Hawaii (4) and one in 350,000 live births in Japan (5).

To date, only five patients with CF have been reported in Korea and they all presented with respiratory symptoms rather than pancreatic insufficiency (6-9). We report a Korean infant with CF who had steatorrhea and failure to thrive. CF was confirmed by a sweat chloride test and genetic analysis and the infant was treated successfully with fat-soluble vitamin supplementation and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 9-month-old female infant was admitted to our hospital because of greasy stools and failure to thrive. She had been well until two months of age, when a productive cough and fever developed. She was hospitalized twice with recurrent pneumonia, which was treated with antibiotics. At three months of age, failure to thrive was noted and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was isolated from sputum cultures obtained by ventilating bronchoscopy. At seven months of age, her parents were aware of her greasy and foul-smelling loose stools that were often pale; the infant also showed poor appetite. The patient had been born to a nonconsanguineous healthy couple by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 weeks of gestation. The patient's birth weight was 2.60 kg and there was no history of delayed passage of meconium. She had a 6-yr-old brother and the family history was unremarkable.

On admission, the infant appeared to be malnourished but was not in acute distress. The body weight was 4.5 kg (<3rd percentile for age), height 54.7 cm (<3rd percentile), and head circumference 33 cm (<3 percentile). The patient's vital signs included a temperature of 36.9℃, heart rate of 130 beats per minute and respiratory rate of 40 per minute. Her chest was not retracted and her breathing sounds were clear. The abdomen was not distended and the bowel sounds were normal. There was no organomegaly. No digital clubbing was found and a neurologic examination was negative.

A complete blood count and serum electrolytes were all within the normal limits. The serum albumin level was 2.6 g/dL and cholesterol was 100 mg/dL. AST and ALT levels were 36 U/L and 14 U/L, respectively. Plasma carotene level was 22.5 µg/dL (reference range 50-250 µg/dL). Immunologic studies of the patient were unremarkable, including normal proportions of polymorphonuclear cells, B cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells, and normal immunoglobulin levels. Stool fat was demonstrated microscopically. To confirm the presence of steatorrhea and estimate the quantity of stool fat, an acidified steatocrit test was performed: this gave a value of 33.3% (reference range; 0-6.5%). Stool alpha-1 antitrypsin clearance was 0.49 mL over 24 hr, which was within the normal limits. Chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans revealed segmental atelectasis and patchy infiltration. An abdomen CT scan showed normal pancreas and hepatobiliary systems.

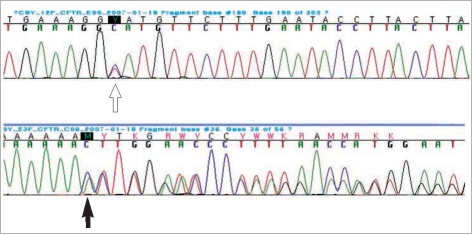

CF was suspected on the basis of isolation of MRSA in the respiratory tract, recurrent respiratory infection, and fat malabsorption. A quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test was performed, showing the average sweat chloride concentration on both thighs to be 102.0 mM/L (reference limit <40 mM/L). After obtaining informed consent from the parents, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. Direct sequence analysis of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene was performed as described (9). This identified compound heterozygous mutations composed of a novel splicing mutation in intron 12 (c.1766+2T>C) and a 1-bp duplication in exon 21 resulting in a frameshift mutation (c.3908dupA; Asn1303LysfsX6) (Fig. 1). The parents declined further genetic analysis and sweat testing of the family.

Fig. 1.

Direct sequencing of the CFTR gene. A novel splice site mutation (c.1766+2T>C, open arrow) and a novel 1-bp duplication (c.3908dupA; Asn1303LysfsX6, filled arrow) were identified.

Pancreatic enzymes (lipase 25,000 IU), fat-soluble vitamins, and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids were given to treat the infant's pancreatic insufficiency. She was fed with breast milk and standard infant formula. With pancreatic enzyme replacement, the steatorrhea improved and the infant gained weight slowly. She was thriving and passing formed stools by one year after hospital discharge. Her weight was at the 3rd percentile for age and her height was at the 10th percentile.

DISCUSSION

We describe a Korean infant with CF who had steatorrhea and failure to thrive. Initially the patient presented with recurrent pulmonary infections. Failure to thrive had been regarded as the consequence of chronic pulmonary infections. Chest CT revealed chronic lung disease and MRSA was cultured from her sputum. The low plasma carotene level indicated malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamin A. The increase in acid steatocrit was indirect evidence of pancreatic insufficiency. This test can be performed accurately on random spot stools and can be used to detect the presence of steatorrhea and to estimate fecal fat quantitatively (10). CFTR sequencing demonstrated compound heterozygous mutations and the sweat test was positive, so CF was diagnosed in this patient. Pancreatic enzyme replacement and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation led to the improvement of the patient's steatorrhea and catch-up growth by one year after discharge from hospital.

Patients are described as having pancreatic insufficiency when they have measurable steatorrhea, but this does not occur until only about 1-2% of pancreatic enzymatic secretory capacity remains (11). Pancreatic insufficiency results in the loss of amylase, lipase, and protease activities, as well as bicarbonate secretion. Lipases are the primary enzymes used to hydrolyze fat which is important in infants and young children as the primary source of energy. Pancreatic insufficiency is present in 89% of individuals with CF (12). The remaining 10% of patients have sufficient preservation of pancreatic function to prevent steatorrhea. Pancreatic function should be tested for the initial diagnosis of CF and monitored subsequently to delineate any changeover from pancreatic sufficiency to insufficiency (13). Wasting is a significant predictor of survival in patients with CF independent of lung function. Enzyme therapy improves nutrient absorption and, with appropriate dietary therapy, normal nutritional status can be expected in most patients with CF (1).

CF is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations of the gene located on chromosome 7. The gene product is CFTR, which regulates the transport of electrolytes across epithelial cell membranes (14). More than 1,500 different mutations have been identified so far (http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr/). CFTR mutation patterns in Asian populations are different from those observed among Caucasians (15, 16). The F508del genotype, which accounts for 66% of CF cases worldwide, is very rare in the Korean population (16), and four mutations reported in Korean patients with CF are not commonly seen in Caucasians (8, 9). We found two novel mutations in this patient, which have not been reported in Caucasians.

The genotype of CFTR is associated with pancreatic insufficiency. Previous genotype and phenotype analyses showed that nonsense, frameshift, and splice junction mutations are associated with the pancreatic insufficiency phenotype (17). Mutations leading to CF have grouped into five classes according to the mechanism by which the mutation affects normal CFTR protein function. Class I mutations fail to produce CFTR proteins because of the presence of nonsense, frameshift, or splice mutations (18). Our patient harbored a heterozygous splicing mutation and a heterozygous frameshift mutation, which might result in defective production and severe phenotype. She showed pancreatic insufficiency and required pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. Previous Korean patients with CF, including children and adults, did not show pancreatic insufficiency (6, 8, 9).

In summary, we treated an infant with CF and pancreatic insufficiency. CF was diagnosed by a sweat chloride test and CFTR genetic analysis. Pancreatic enzyme replacement produced adequate weight gain and resumption of growth in the patient. CF should be considered in patients with steatorrhea and failure to thrive.

References

- 1.Sinaasappel M, Stern M, Littlewood J, Wolfe S, Steinkamp G, Heijerman HG, Robberecht E, Doring G. Nutrition in patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2002;1:51–75. doi: 10.1016/s1569-1993(02)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker SS, Borowitz D, Duffy L, Fitzpatrick L, Gyamfi J, Baker RD. Pancreatic enzyme therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2005;146:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boat TF, Acton JD. Cystic fibrosis. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 1803–1816. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright SW, Morton NE. Genetic studies on cystic fibrosis in Hawaii. Am J Hum Genet. 1968;20:157–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashiro Y, Shimizu T, Oguchi S, Shioya T, Nagata S, Ohtsuka Y. The estimated incidence of cystic fibrosis in Japan. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:544–547. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon HR, Ko TS, Ko YY, Choi JH, Kim YC. Cystic fibrosis: a case presented with recurrent bronchiolitis in infancy in a Korean male infant. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:157–162. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1988.3.4.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SH, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Park CH. Cystic fibrosis: case report. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2002;47:693–696. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn KM, Park HY, Lee JH, Lee MG, Kim JH, Kang IJ, Lee SI. Cystic fibrosis in Korean children: a case report identified by a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test and genetic analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:153–157. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh WJ, Ki CS, Kim JW, Kim JH, Lim SY. Report of a Korean patient with cystic fibrosis, carrying Q98R and Q220X mutations in the CFTR gene. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:563–566. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amann ST, Josephson SA, Toskes PP. Acid steatocrit: a simple, rapid gravimetric method to determine steatorrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2280–2284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borowitz D. Update on the evaluation of pancreatic exocrine status in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:524–527. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000181474.08058.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borowitz D, Baker SS, Duffy L, Baker RD, Fitzpatrick L, Gyamfi J, Jarembek K. Use of fecal elastase-1 to classify pancreatic status in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2004;144:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walkowiak J. Assessment of maldigestion in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2004;145:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern RC. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:487–491. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li N, Pei P, Bu DF, He B. A novel CFTR mutation found in a Chinese patient with cystic fibrosis. Chin Med J. 2006;119:103–109. doi: 10.3901/jme.2006.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Choi JH, Namkung W, Hanrahan JW, Chang J, Song SY, Park SW, Kim DS, Yoon JH, Suh Y, Jang IJ, Nam JH, Kim SJ, Cho MO, Lee JE, Kim KH, Lee MG. A haplotype-based molecular analysis of CFTR mutations associated with respiratory and pancreatic diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2321–2332. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristidis P, Bozon D, Corey M, Markiewicz D, Rommens J, Tsui LC, Durie P. Genetic determination of exocrine pancreatic function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:1178–1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch C, Cuppens H, Rainisio, Madessani U, Harms H, Hodson M, Mastella G, Navarro J, Strandvik B, McKenzie S. European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis (ERCF): comparison of major disease manifestations between patients with different classes of mutations. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200101)31:1<1::aid-ppul1000>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]