Abstract

The theories of signal sampling, filter banks, wavelets, and “overcomplete wavelets” are well established for the Euclidean spaces and are widely used in the processing and analysis of images. While recent advances have extended some filtering methods to spherical images, many key challenges remain. In this paper, we develop theoretical conditions for the invertibility of filter banks under continuous spherical convolution. Furthermore, we present an analogue of the Papoulis generalized sampling theorem on the 2-Sphere. We use the theoretical results to establish a general framework for the design of invertible filter banks on the sphere and demonstrate the approach with examples of self-invertible spherical wavelets and steerable pyramids. We conclude by examining the use of a self-invertible spherical steerable pyramid in a denoising experiment and discussing the computational complexity of the filtering framework.

Index Terms: Channel bank filters, feature extraction, filtering, frequency response, image sampling, image orientation analysis, spheres, spherical images, wavelet transforms

I. INTRODUCTION

Multiscale filtering methods, such as wavelets [7] and “overcomplete wavelets” [9], [23], [25] have many applications in feature detection, compression, and denoising of planar images. Extending the theories and the methods of filtering to spherical images promises similar benefits in the fields that give rise to such images, including shape analysis in computer vision [5], illumination computation in computer graphics [21], [22], cosmic background radiation analysis in astrophysics [26], [29] and brain cortical surface analysis in medical imaging [32], [33].

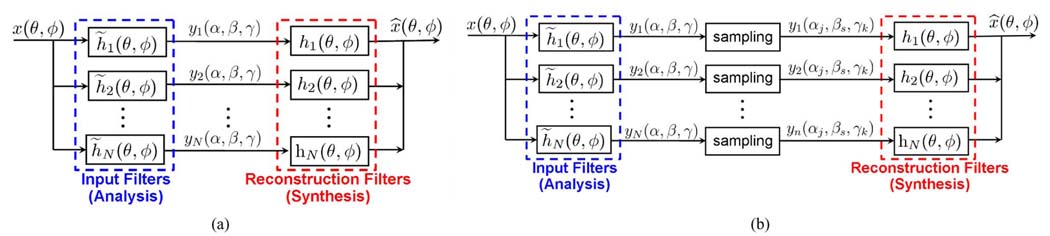

We consider a two-stage filtering framework [Fig. 1(a)], conceptually equivalent to the usual Euclidean filtering framework except the planar images and filters are replaced by spherical ones. We can think of the first set of filters as analysis filters which project the input image onto the space spanned by the analysis filters. A reconstructed image is then obtained by passing the intermediate outputs through the second layer of filters. Fig. 1(b) shows a modification of the framework in Fig. 1(a) that introduces sampling between the first and the second layers of filters. The sampling is useful if one is interested in processing the outputs of the analysis filters before passing them through the synthesis filters.

Fig. 1.

Continuous and discrete filter bank diagram. (a) Continuous filter bank. (b) Discrete filter bank.

In this work, we analyze the relationship between the reconstructed image and the original image, and establish conditions under which the reconstructed image is the same as the original one, i.e., conditions for invertibility. We demonstrate the use of our results on continuous invertibility and generalized sampling for designing filter banks that enable explicit control of both analysis and synthesis filters. We illustrate the framework by creating examples of self-invertible spherical wavelets and steerable pyramids.

Self-invertible filter banks employ identical filters for analysis and synthesis. Self-invertibility is desirable for image manipulation in the wavelet domain, leading to an intuitive notion that a convolution coefficient corresponds to the contribution of the corresponding filter to the reconstructed signal. Without self-invertibility, the effects of nonlinear processing of wavelet coefficients could propagate to spatial locations and frequencies other than those which were used to compute the coefficients [23]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first approach demonstrated on a sphere that enables the design of self-invertible filter banks.

II. RELATED WORK

In the Euclidean domain, convolution is computed efficiently using the fast Fourier transform (FFT) [6]. Once we move to the sphere, FFT must be replaced with an alternative efficient method for computing convolutions. An original algorithm for axisymmetric convolution kernels on the sphere was derived in [11] and was recently extended to arbitrary functions [28], [30]. These results allow us to efficiently compute the outputs of the first set of filters. Unfortunately, they do not apply to the inverse convolution with the second layer of filters because the outputs of the first layer of filters are in general not spherical images as we will see in Section III.

In the past decade, there has been much work on extending the general paradigm of linear filtering to the spherical domain [1], [4], [8], [12], [13], [17], [21], [22], [26], [29]. For example, the lifting scheme in [21] and [22] adopts a nonparametric approach to computing the wavelet decomposition of arbitrary meshes by generalizing the standard two-scale relation of Euclidean wavelets. This method enables a multiscale representation of the original mesh (image) with excellent compression and speed performance. However, the lifting wavelets are not overcomplete, i.e., exactly one wavelet coefficient is created per sample point, causing difficulties in designing filters for oriented feature detection and invariance to rotation [33].

A similar problem in the Euclidean domain leads to the invention of “overcomplete wavelets,” such as steerable pyramids [14], [23]. A group theoretic formulation of overcomplete continuous spherical wavelets is proposed in [1]. In particular, it can be shown that the stereographic projection of an admissible planar wavelet to the sphere is also admissible under the group theoretic framework, providing a straightforward framework for the design of analysis filters for specific features of interest, such as oriented edges [29].

In the group theoretic approach, defining the mother wavelet completely determines the analysis and synthesis filters. However, while the analysis filters are related by stereographic dilation, the synthesis filters are in general not related by dilation. In fact, the support of corresponding analysis and synthesis filters is guaranteed to be the same in frequency domain but not in the spatial domain. Bogdanova et al. [4] discretize the group theoretic wavelets, providing a sampling guarantee for the framework of Fig. 1(b) for the restricted class of axisymmetric filters. An axisymmetric spherical function is one which is symmetrical about the north pole. This work is, therefore, the most similar to ours. In contrast, we study general filter banks, without any restriction on the relationships among the cascade of filters. We derive the analogue of the Papoulis generalized sampling theorem [18] on the sphere, applicable to both axisymmetric and nonaxisymmetric filters.

Driscoll and Healy [11] provide the equivalent of the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem on the sphere. While the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem provides reconstruction guarantees for bandlimited signals in Euclidean space under perfect sampling (convolution with a delta function), the Papoulis generalized sampling theorem provides guarantees for bandlimited signals sampled via convolutions with kernels of sufficient bandwidth.

An earlier version of this work was first presented at the International Conference on Image Processing [31]. In this paper, we include proofs of the invertibility conditions and demonstrate the generation of self-invertible spherical steerable pyramids. In Section III, we introduce the notation used throughout the paper. In Section IV, we present the main theoretical contributions of this paper: continuous invertibility and the generalized sampling theorem. We propose a procedure for generating self-invertible multiscale filter banks on the sphere in Section V. In Section VI, we illustrate the procedure to design wavelets and steerable pyramids and employ a steerable pyramid in denoising. We conclude with the discussion of future research and outstanding challenges in the proposed framework.

To summarize, our contributions are as follows.

We present theoretical conditions for the invertibility of axisymmetric and nonaxisymmetric filter banks under continuous spherical convolution.

We present a generalized sampling theorem of signals on the 2-Sphere for both axisymmetric and nonaxisymmetric filter banks. This generalizes the works of Bogdanova et al. [4] and Starck et al. [26] to nonaxisymmetric filters and opens a way for nonlinear processing of the wavelet coefficients generated from general filter banks.

We present a mechanism for generating invertible, as well as self-invertible, wavelets, and steerable pyramids. We provide an analysis of the computational complexity of the filtering framework.

III. DEFINITIONS

Let x(θ,ϕ) ∈ L2(S2) be a square-integrable function on the 2-D unit sphere, where (θ,ϕ) are the spherical coordinates. Suppose P = (θ,ϕ) is a point on the sphere. Then, θ ∈ [0, π] is the co-latitude, which is the angle between the positive z-axis (north pole) and the vector corresponding to P. ϕ ∈ [0, π] is the longitude and is taken to be the angle between the positive x-axis and the projection of P onto the x – y plane. ϕ is undefined on the north and south poles.

The spherical harmonics [20] form an orthonormal set of basis functions for L2(S2): i.e.,

| (1) |

where is xl,m the spherical harmonic coefficient of degree l and order m obtained by projecting the function x(θ, ϕ) onto

| (2) |

where dΩ = sin θdθdϕ and * denotes complex conjugation. We call a spherical harmonic of degree l and order m. We note that for axisymmetric functions (independent of ϕ), only the order 0 harmonics are nonzero. A more detailed background of spherical harmonics is found in Appendix A.

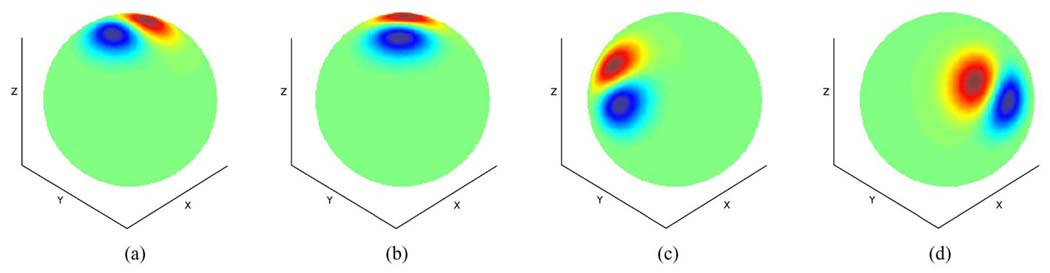

We choose to parameterize rotations on the sphere by the Euler angles, α,β,γ (α ∈ [0,2π],β ∈ [0,π],γ ∈ [0,2π]). The rotation operator D(α,β,γ) first rotates a function by γ about the z-axis [Fig. 2(b)], then by β about the y-axis [Fig. 2(c)], and finally by α about the z-axis [Fig. 2(d)]. The direction of positive rotation follows the right-hand screw rule. The three angles specify an element of the rotation group SO(3) and provide a natural parametrization of convolution on the sphere. The effects of rotation on the spherical harmonic coefficients of a function is expressible in terms of the so-called Wigner-D functions. The Wigner-D functions form an irreducible representation of the rotation group [20]. Appendix A provides the explicit expressions for the Wigner-D functions.

Fig. 2.

Rotation via euler angles (α, β, γ). (a) Original spherical image. (b) Rotation by γ about z-axis. (c) Rotation by β about y-axis. (d) Rotation by α about z-axis.

A. Continuous Convolution

On the plane, convolution is defined in terms of the inner product between two functions translated relative to each other, and is parameterized by the amount of translation. On the sphere, it is more natural to talk about rotation rather than translation, and, therefore, spherical convolution is parameterized by rotation. Given a spherical image x(θ,ϕ) and a spherical filter h̃(θ,ϕ), their spherical convolution

| (3) |

is a function of L2(SO(3)) rather than L2(S2). This definition of convolution is identical to that in [28], [30], although [30] calls it directional correlation.

By convention, we shall consider the center (origin) of a spherical filter to be at the north pole (θ = 0). Then intuitively,y(α, β, γ) is the inner product between the re-oriented filter D(α, β, γ)h̃ [e.g., Fig. 2(d)] and the spherical image. In other words, we obtain y(α, β, γ) by first re-orienting the spherical filter by a rotation of γ about the z-axis (center still at north pole), then bringing the center of the filter to the point (β, α) of the spherical image, and performing an inner product between the image and filter. Therefore, y(α, β, γ) is the correlation of the rotated version of h̃ with x, or the projection coefficient of x onto [D(α, β, γ)h̃]. In the case of the filter shown in Fig. 2, a high value of y(α, β, γ) would imply a presence of an oriented edge at spherical coordinate (β, α) with orientation γ.

We note that the notion of orientation is inherently local here because a continuous unit-norm vector field does not exist on the sphere. Therefore, it is not meaningful to claim an existence of an edge of orientation γ at location (β, α) without specifying a local coordinate system. In our case, we can define such a local coordinate system by first specifying one at the north pole. Our choice of parameterizing rotation via the Euler angles then induces a local coordinate system everywhere, except the south pole.

For axisymmetric filters, h̃(θ,ϕ) = h̃(θ), the rotation by γ about the y-axis has no effect, i.e., y(α, β, γ) = y(α, β) is a spherical image parametrized by θ = β,ϕ = α.

To project a function in L2(SO(3))onto L2(S2), we define the inverse convolution of a spherical filter h(θ,ϕ) with y(α, β, γ) ∈ L2(SO(3)) to be

| (4) |

where the integration is over the Euler angles: dρ = sin βdαdβdγ. Our definition of inverse convolution generalizes the spherical convolution between two functions on S2 defined by Driscoll and Healy [11], and is identical to theirs if y(α, β, γ) = y(β, α), i.e., a spherical image. Our inverse convolution operation is similar to the transpose convolution operation defined in [2], [28]. However, the transpose convolution uses the uniform measure dαdβdγ, ignoring the intrinsic nonuniform component sin β of the measure on SO(3).

We can think of the inverse convolution in the following intuitive way. The reconstructed value at a given (θ,ϕ) is obtained by summing (integrating) the contributions of the rotated reconstruction filters h, centered at all possible positions (β, α) and oriented by all possible angles γ, where the weights of the contributions are given by the convolution outputs (projection coefficients on the corresponding input filters).

We distinguish between the forward convolution (3) and the inverse convolution (4) because the forward convolution combines two spherical images to give a function on SO(3), while the inverse convolution combines a spherical image and a function on SO(3) to give a spherical image. Both definitions of convolutions generalize the concept of convolution in Euclidean spaces.

When using a filter bank of N analysis-synthesis filter pairs [Fig. 1(a)], the reconstructed signal is obtained by summing the response of all filter pairs

| (5) |

which is analogous to the definition in [1], with integration over scale replaced by summation over the filter index.

B. Discrete Convolution

In the Euclidean case, we typically discretize both the input images and the convolution outputs. When working on the sphere, we choose to keep the image domain continuous by working with spherical harmonic coefficients rather than sample values, because this allows us to exploit efficient algorithms for spherical convolution [28], [30]. Since no uniform sampling grid exists on the sphere, performing convolution completely by quadrature would be slow. This is because under each rotation of the filter relative to the spherical image, we would need to re-sample (or re-interpolate) the filter or the image.

For L2(SO(3))(or equivalently, in the spherical wavelet domain), continuous representation is possible through series of complex exponentials [28] or Wigner-D functions [30]. However, both the complex exponentials and the Wigner-D functions have global support. Therefore, in applications where we want to modify the image in the wavelet domain, manipulating the series coefficients would be tantamount to simultaneously altering all the wavelet coefficients, defeating the purpose of the wavelet decomposition, which is to provide localized control in both spatial and frequency domain. To avoid this, we sample the output of the continuous convolution y(α,β,γ) to create its discrete counterpart y(αj, βs,γk), where {αj, βs,γk} define a particular sampling grid [Fig. 1(b)]. The inverse convolution between the sampled projection coefficients yj,s,k and the continuous reconstruction filters h is then defined as

| (6) |

which includes sampling-dependent quadrature weights wj,s,k, introduced so that the discrete case converges to the continuous case as the number of samples increases. This definition allows for an easy transfer of continuous filtering theory to its discrete analogue. In Section IV, we show that “good” choices of wj,s,k exist, corresponding to different sampling schemes. In contrast with the Euclidean case, wj,s,k are necessary because of the nonuniform measure on the Euler angles dρ = sin βdαdβdγ, as we discuss in Section IV.

Similar to the continuous case [cf. (4)], the signal reconstructed through N analysis-synthesis filter pairs is defined as a sum of contributions of all filter pairs

| (7) |

The sampling grid and the quadrature weights now depend on n since different filters in the filter bank might use different sampling schemes.

IV. INVERTIBILITY CONDITIONS

In this section, we present the main theoretical contributions of our work.

1) Theorem 4.1: (Continuous Frequency Response)

Let be an analysis-synthesis filter bank. Then for any spherical image x ∈ L2(S2) and its corresponding reconstructed image x̂

| (8) |

where xl,m and x̂l,m are the spherical harmonic coefficients of the input and reconstructed images, respectively. and are the spherical harmonic coefficients of the nth analysis and synthesis filters, respectively.

Appendix B presents the proof of Theorem 4.1. To draw an analogy with the Euclidean case, we call

| (9) |

the frequency response of the analysis-synthesis filter bank. Note that the degree l spherical harmonics coefficients of the reconstructed image are affected only by the degree l spherical harmonic coefficients of the filters. However, the degree l order m spherical harmonic coefficient of the reconstructed signal is affected by all the orders of degree l spherical harmonic coefficients of the filters. In contrast, on the plane, the frequency response is simply the sum of products of the Fourier coefficients of the analysis and the synthesis filters

| (10) |

where ℱ{x̂}(s1,s2), ℱ{x}(s1,s2), ℱ{h̃}(s1,s2) and ℱ{hn}(s1,s2) denote the Fourier transforms of the reconstructed signal, original signal, analysis filters and synthesis filters respectively. We note that under Euclidean space conventions, a “self-invertible” filter bank is one with h̃n(x,y) = hn(−x,−y) and . We see that the effects of s1 and s2 are separable, unlike l and m. Furthermore, on the sphere, the frequency response contains an extra modulating factor that decreases with degree l. The following corollary of Theorem 4.1 provides the necessary and sufficient condition for the invertibility of filter banks under continuous convolution.

2) Corollary 4.2: (Continuous Invertibility)

Let be an analysis-synthesis filter bank. Then for any spherical image x ∈ L2(S2) and its corresponding reconstructed image x̂

| (11) |

We note that the corollary is easily satisfied if there is no constraint on the relationships among the cascade of filters: given a set of analysis filters h̃n, there are in general multiple sets of synthesis filters that can achieve invertibility. For example, we can define the synthesis filters to be hn = Lψh̃n, where

| (12) |

and Hh̃,h̃ (l) is the frequency response defined in (9). Lψ is a frequency modulating operator that normalizes the synthesis filters at each degree, such that the combined frequency response of the filter bank is 1 for all l with Hh̃,h̃ (l) > 0. This filter bank is, therefore, invertible over the frequency range of the support of the filters. This operation is similar to the frame operator in the continuous spherical wavelet transform of [1], where the counterpart of Hh̃,h̃ (l) is given by , replacing the summation over n by the integration over the scale a, with measure 1/a3da. For the special case of the analysis filters being dilated versions of each other, this choice of the synthesis filters is a direct discretization of [1], albeit ignoring the measure of a. The complete discretization of the continuous wavelet transform in [1] is actually accomplished in [4]. However, regardless of using Lψ or the frame operators of [1], [4], the synthesis filters are in general not related by dilation even if the analysis filters are.

We now define L̃n (Õn) and Ln (On) to be the highest nonzero harmonic degree (order) of h̃n and hn, respectively. The following result relates the spherical harmonics coefficients of the input image xl,m and reconstructed image x̂l,m under the sampling framework of Fig. 1(b).

3) Theorem 4.3: (Generalized Sampling Theorem)

Let be a filter bank with L̃n (and, thus, Õn) < ∞ and Ln (and, thus, On) < ∞. Suppose the sampling grid and the quadrature weights satisfy:

αj,n = 2πj/(L̃n + Ln + 1) for j = 0, 1, … ,(L̃n + Ln);

γk,n = 2πk/(Õn + On + 1) for k = 0, 1, …, (Õn + On);

- ws,n and βs,n and are the quadrature weights and knots such that

for l ≤ Ln,l′ ≤ L̃n, where are the Wigner-d functions;(13) - wj,s,k,n = 4π2ws,n/((L̃n + Ln +1)(Õn + On + 1)). Then

(14)

Appendix A provides the definitions and the explicit expressions for the Wigner-d functions. Note that there is an implicit link between the number of samples Sn and the bandwidths L̃n and Ln (see Appendix D). The constraints in this theorem ensure that the number of samples remain finite and is similar to the tradeoff between the number of points in a spherical grid and the maximum bandwidth of signals defined on it [11]. The samples and the weights are picked such that the discrete reconstruction defined in (7) gives the same result as the continuous version in (5). The proof is found in Appendix C. In Appendix D, we demonstrate two sets of quadrature weights and knots that satisfy the conditions of the theorem. We note that the use of quadrature methods as tools for sampling proofs was previously employed in the fast spherical transform [11], [15] and the fast Wigner-D transform (SOFT) [16].

The measures corresponding to α and γ are constants in SO(3), just like in the Euclidean space. We, therefore, use uniform sampling for these parameters in our work. For discrete planar convolution, it is customary to have no weights (or rather, unit weights). On the sphere, however, the nonuniform measure on β, sin βdβ, presents challenges for sampling. If we are simply interested in convergence, then setting wj,s,k = (2π/J)(2π/S) sin(βs(2π/K) for uniform samples of α, β, γ corresponds to the Riemann sum of the integral. Theorem 4.3 states that better quadrature schemes exist that allow for faster convergence with finite numbers of samples.

The continuous invertibility corollary and the generalized sampling theorem imply the following:

4) Corollary 4.4: (Discrete Invertibility)

Consider a filter bank of filters with finite maximum spherical harmonic degrees. There exists quadrature schemes such that the filter bank is invertible over a particular frequency range under the discrete spherical convolution if the filter bank is also invertible over the same frequency range under the continuous spherical convolution.

Because functions in L2(S2) have finite energy, their spherical harmonic coefficients must necessarily decay to zero. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that the filters of the filter bank are of finite bandwidth as required by Theorem 4.3 by representing the filters with a finite number of coefficients up to an arbitrary prespecified precision. We will, therefore, focus on constructing invertible filter banks for continuous convolution.

The discrete invertibility corollary opens a way for nonlinear processing of the wavelet coefficients generated from general filter banks. Applications may include compression, denoising and image enhancement. The corollary also enables the perfect reconstruction of an original signal sampled with equipment that introduces blurring during the acquisition process. For example, the first layer of filters h̃n could be the blurring kernels of a set of N radio dishes measuring the cosmic background radiation of the sky. We can then hope to recover the true cosmic background radiation signal by passing the recorded signal through the second bank of filters.

V. CONSTRUCTING SELF-INVERTIBLE MULTISCALE FILTER BANKS

In this section, we show how to use the continuous invertibility corollary to generate self-invertible multiscale filter banks. The optimization framework presented here can be easily adapted to design other types of filter banks by altering the structure of the optimization problem according to an application’s needs.

For self-invertible filter banks, h̃n (θ,ϕ) is constrained to be the same as hn(θ,ϕ). Furthermore, in multiscale analysis, the analysis filters are related through dilation and scaling of a particular template h̃(θ,ϕ), i.e.,

| (15) |

where bk ≥ 1 and Dan is the nonlinear dilation operator,1 both of which will be explained shortly. We use the convention that larger n corresponds to smaller a (narrower filters),

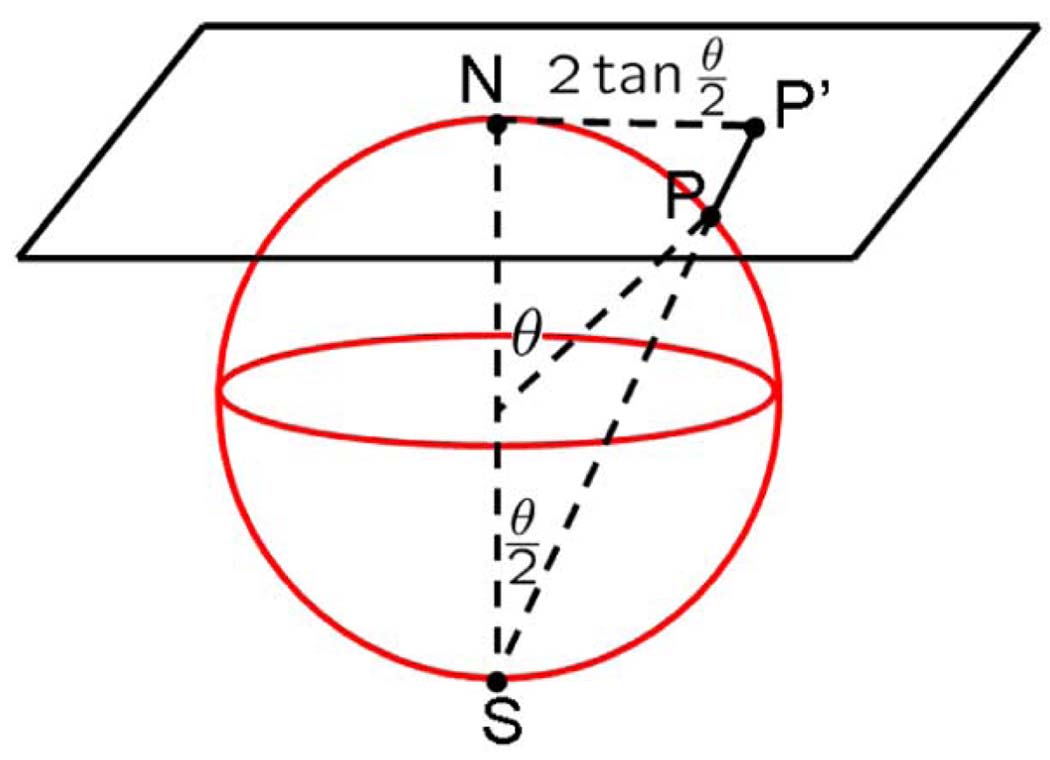

In this paper, we adopt the stereographic dilation operator introduced in [1] (Fig. 3), which involves stereographically projecting the function from the sphere onto the tangent plane of the north pole, performing the usual dilation operation on the plane and then projecting the resulting function back onto the sphere2

| (16) |

The normalization factor ( 1 + tan2(θ/2)) / (1 + ((1 /a)tan(θ/2))2 ensures the inner product between functions is conserved under stereographic dilation. Stereographic dilation allows for an explicit control of the spatial localization of the wavelets in contrast with previous approaches that define dilation in the frequency domain [4]. Because of the nonlinear nature of stereographic dilation, extreme dilation of a spherical function will eventually lead to high frequencies. Initial dilation of a function localized at the north pole increases the support of the function and results in lower frequencies. As dilation continues, oscillations will accumulate near the south pole, resulting in high frequencies. A useful analysis of this phenomenon can be found in Bogdanova et al. [4]. In practice, we will avoid working in that region, since the dilated filter no longer looks like the original filter.

Fig. 3.

Stereographic dilation. Correspondence between the spherical surface and tangent plane is established via stereographic projection: point P on the sphere is mapped to the point P′ on the tangent plane of the north pole. This allows a spherical function f(θ ϕ) to be mapped onto the tangent plane. The usual dilation is then performed on the tangent plane. The resulting dilated function is mapped back onto the sphere via stereographic dilation: (1/a)f(2 tan−1 ((1/a) tan(θ/2));ϕ). The normalization factor (1 / tan2 (θ/2))/(1+ ((1/a) tan (θ/2))2) is added to conserve the inner product between dilated functions.

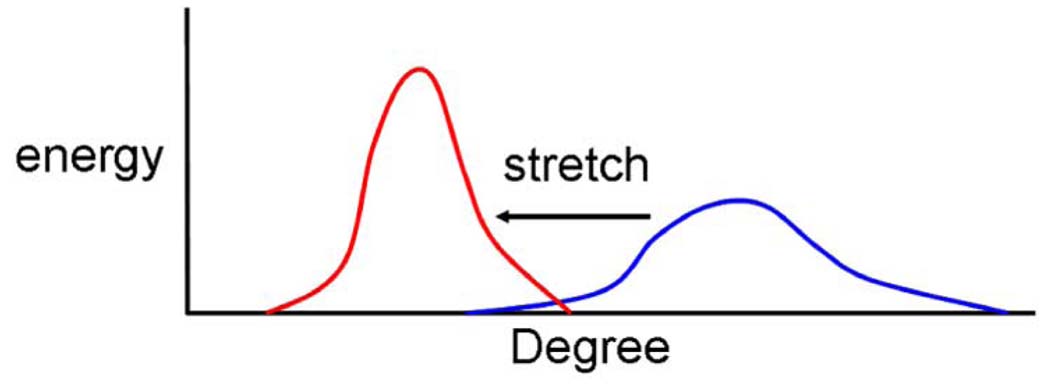

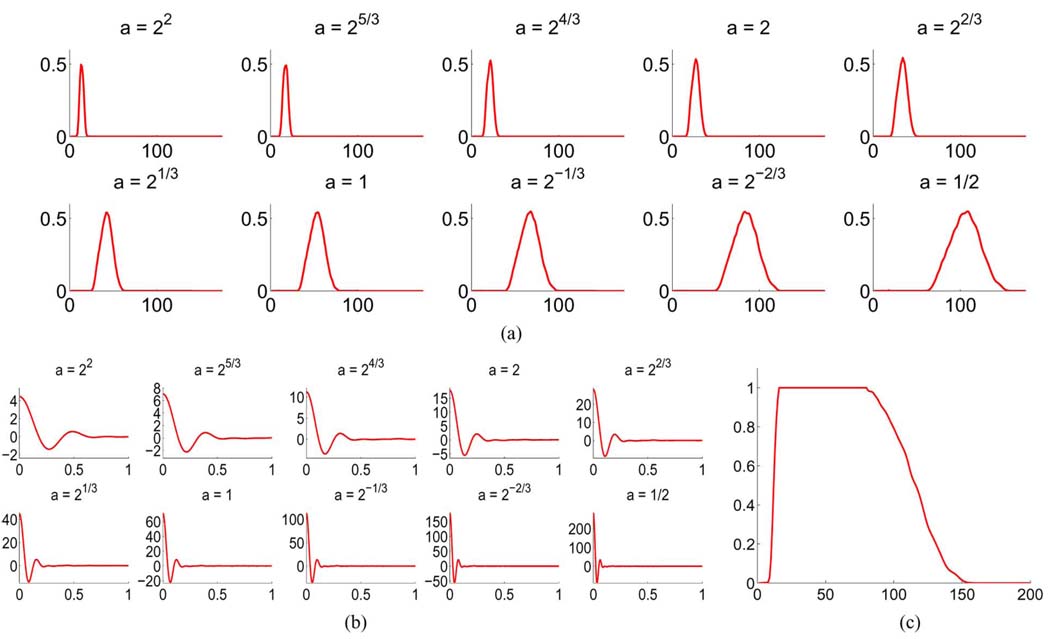

The bk’s in (15) are the amplitude scaling parameters that control the tradeoff between self-invertibility and norm-preserving dilation. Corollary 4.2 implies that the sum of squares of the spherical harmonic coefficients of a bank of self-invertible filters must increase linearly with degree. But stretching a function while preserving its norm shifts its spherical harmonic coefficients to the left (spherical harmonic degrees decrease) and magnifies them (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect on energy due to norm preserving stereographic dilation.

These extra weights are analogous to the measure of scale 1/a3da in the group theoretic formulation of spherical wavelets [1] and its discretization in the axisymmetric case [4], resulting in wider filters being assigned smaller weights. On the continuous real line, the measure 1/a2da nicely cancels out the dilation of the filter (cf. [27, Ch. 5]). On the discrete real line, the convolution outputs of narrower filters are sampled more densely. This suggests two possible approaches: variable sampling of the convolution outputs or variable scaling of the filters. Yet another approach is to sample the scale space unevenly rather than according to a power law. Because the effects of stereographic dilation on the spherical harmonic coefficients of a function are not analytical, none of these approaches leads to a closed-form solution. In this paper, we take the variable scaling approach by finding the appropriate bk’s as part of the filter design.

Fortunately, stereographic dilation is distributive over addition. Suppose the template h̃ is expressible as a linear combination of the basis functions Bi(θ,ϕ) i.e., . Here, we assume that Bi(θ,ϕ) are spherical harmonics and note that the technique is still applicable if a more suitable basis is found, such as described in [24]. Applying stereographic dilation to h̃

| (17) |

yields the spherical harmonic coefficients of the analysis filter at another scale. This is useful since the invertibility condition in Corollary 4.2 is expressed in terms of the spherical harmonic coefficients of the filters. We can, therefore, decide on a set of scales and precompute a table of spherical harmonic coefficients of the dilated basis functions [DaBi]l,m. Equation (17) allows us to determine the spherical harmonic coefficients of the dilated filters at each relative scale given and . This technique can also be applied to other definitions of scale that are distributive over addition.

After fixing the set of basis functions {Bi} and the set of scales {an}, we now pose a constrained optimization problem to determine c⃗ and b⃗. Similarly to the filter design in the Euclidean space, the objective function should be application dependent, and could for example be a function of the frequency response. The constraints come from enforcing self-invertibility: we assume that the analysis and synthesis filters are identical and optimize the cost function under the invertibility constraints of Corollary 4.2. Since we cannot have more constraints than variables, self-invertibility cannot be achieved for more degrees than the number of basis functions and scales. We will discuss several specific examples of the objective function in Section VI.

The quadratic penalty method [3] is effective in solving this optimization problem with nonconvex constraints by incorporating the constraints into the objective function and solving the resulting unconstrained optimization problem using nonlinear least squares minimization

| (18) |

The first term corresponds to the invertibility conditions by constraining the frequency response Hc⃗,b⃗(l) ((9)) to be 1. The sum in the first term is over the desired invertibility range. Note that c⃗ and b⃗ completely determine the first term since they define the filter bank {h̃an, han} via (15) and (17). The vector valued functions Γ⃗n in the second term reflect the (un)desirable properties of the filter bank. For example, Γ⃗ could be the discrete second derivatives of the spherical harmonic coefficients of the filters. Minimizing the norms of Γ⃗n would then lead to smooth filters. We repeat the optimization procedure while increasing the weight λ of the constraints and using the solution corresponding to the previous value of λ as the starting point for the next iteration, until convergence to a local minimum of the original optimization problem. Our implementation uses the Matlab’s lsqnonlin function to minimize the objective function at each iteration.

VI. EXPERIMENTS

In this section, we demonstrate the optimization procedure formulated in the previous section. We demonstrate the construction of both self-invertible spherical wavelets and spherical steerable pyramids. Similar to the Euclidean domain, we define a spherical wavelet transform to be the decomposition of a spherical signal into component signals at different scales, i.e., employing axisymmetric filter kernels. On the other hand, we reserve the term spherical steerable pyramid transform for the decomposition of a spherical signal into component signals at different scales and orientations, i.e., using nonaxisymmetric filter kernels. We note that in some literature [1], [4], [29], the term “spherical wavelets” includes spherical steerable pyramids.

A. Spherical Wavelets

In designing axisymmetric wavelets, we limit our set of basis functions {Bi} to be the first hundred spherical harmonics of order 0, since the spherical harmonic coefficients of axisymmetric functions are zero for orders other than 0.

We define the set of scales to be a = {2−n/3}, n = −6, −5,…,2, 3,with a = 1 (n = 0) corresponding to the undilated template. We use S2kit [15]3 to create a table of the spherical harmonic coefficients of for l = 0,…99. As mentioned earlier, extreme stereographic dilation and shrinking of spherical harmonics can result in high frequencies. We find the first 600 order 0 spherical harmonic coefficients of each dilated spherical harmonic (a dilated axisymmetric function remains axisymmetric). We verify that for a = 4(n = −6) and, .

For axisymmetric filters, we can use the fast spherical convolution [11] to compute the forward convolution (3). We quote the results here for completeness

| (19) |

Furthermore, as noted before, the inverse convolution (4) between two spherical images is the same as the definition of convolution by Driscoll and Healy [11] (except for a conjugation)

| (20) |

Because we seek a multiscale decomposition of the original spherical signal, we would like the filter at each scale to act as a bandpass filter. Similar to the Euclidean domain, we require a residual lowpass filter to ensure that the combined wavelet and the lowpass filter bank is invertible up to a particular degree. Since we only use the first 100 spherical harmonics as our basis, the frequency response of h̃a=1(θ,ϕ) will be zero for all degrees higher than 99. If we also penalize the magnitude of the leading spherical harmonic coefficients of h̃a=1(θ,ϕ), the frequency response of h̃a=1(θ,ϕ) will be zeros at both ends, i.e., it will serve as a bandpass filter. To satisfy the self-invertibility conditions, the solution cannot be identically zero, but must rise to a peak somewhere in the middle of the frequency range.

We also penalize the second derivatives of the filters’ frequency responses and spherical harmonic coefficients to force the filters to be relatively smooth and to reduce ringing. Note that the second derivatives are discrete since spherical harmonic degrees are discrete. We can induce a sharper cutoff frequency by penalizing the magnitude of the combined frequency response above a cutoff degree Lc. In addition, we fix the amplitude scaling factors bk’s (15) to be the same. While allowing the bk’s to take on different values provides the optimization procedure more flexibility in finding a set of desired filters, we find that in practice, having the same b for all the scales results in the frequency responses of the filters at all scales having comparable amplitude. Once again, we note that the energies of the filters at different scales will be different because of Corollary 4.2.

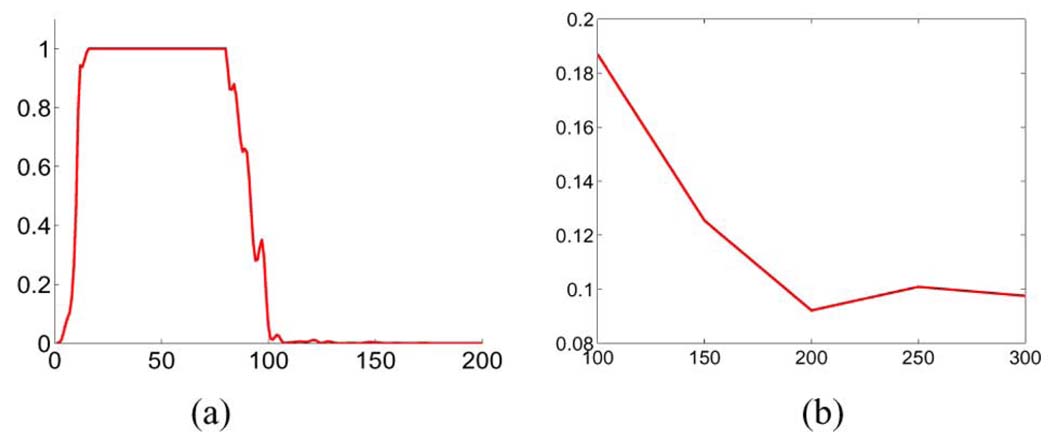

Fig. 5(a) illustrates the frequency response of a ten-scale wavelet filter bank ( a = {2−n/3}, n = −6, −5,…,2, 3) obtained through our optimization procedure. Invertibility is enforced from degree 15 to 79. Furthermore, we impose a quadratic penalty on the magnitude of the combined frequency response for degrees above Lc = 150. The combined frequency response of the filters is shown in Fig. 5(c).

Fig. 5.

Ten-scale wavelet filter bank obtained by imposing invertibility from degree 15 to 79 and a combined frequency response cutoff at Lc = 150. (a) Frequency response of individual filters. (b) Individual filters in the spatial domain (0 ≤ θ ≤ 1 radian). The second peak indicates ringing. (c) Combined frequency response, Lc = 150.

Because the filters are axisymmetric, we can plot the filters in the image domain as a function of θ [Fig. 5(b)]. The existence of a second peak after the peak at θ = 0 (north pole) indicates ringing. When we vary the cutoff frequency penalty, we can trade off the amount of ringing for the slope of the cutoff. For example, Fig. 6(a) shows the combined frequency response of a wavelet filter bank obtained by penalizing the magnitude of the combined frequency response for degrees above Lc = 100. Notice the combined frequency response drops rapidly after degree 79. However, this results in increased ringing. If we measure ringing by the ratio of the second maxima to the maxima at the north pole, we can measure the tradeoff between ringing and the cutoff frequency, as shown in Fig. 6(a).

Fig. 6.

(a) Combined frequency response of the filters obtained when the combined frequency response cutoff is set to Lc = 100. Note the sharper cutoff obtained. However, this is at the expense of ringing. (b) Plot of ringing versus cutoff frequency Lc. Ringing is defined to be the ratio of the second peak to the maximum peak at the lowest scale, a = 4. (a) Combined frequency response, Lc = 100. (b) Ringing versus Lc.

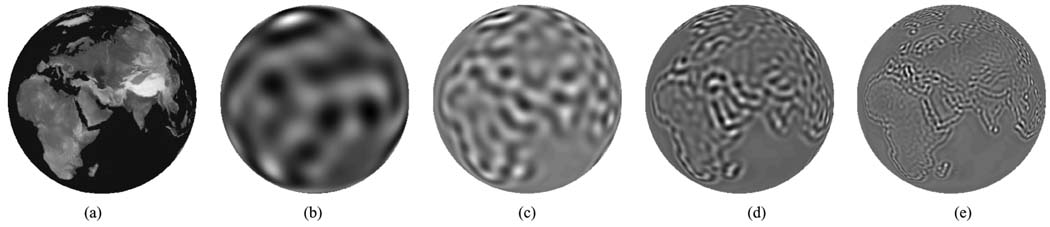

As a verification, we apply the resulting filters to a high resolution world elevation map (size > 1000 × 1000). We bilinearly interpolate the map onto the S2kit [15] grid and convert the spatial image into spherical harmonics using S2kit. This is followed by the inverse transform using S2kit to obtain a final spherical image. The spherical harmonics and the final spherical image become the “ground truth” for measuring invertibility. Lower resolution versions of the elevation map are obtained by truncating the higher degrees spherical harmonics. It is necessary to use the spherical image obtained from inverting the spherical harmonics rather than from the linearly interpolated image because the linearly interpolated image might not be samples from a bandlimited signal. In that case, the sampling theorem of Driscoll and Healy [11] does not hold since the quadrature knots and weights were computed assuming samples from a bandlimited signal. This is in contrast to the Euclidean case, where the forward and inverse discrete Fourier transform always return the same results. As a result, the fast spherical harmonic transform of S2kit is not completely invertible for nonbandlimited signals and is instead an approximate fit of the linearly interpolated data. The final spherical image and the spherical harmonics are, however, exact inverses of each other.

We convolve the wavelet filter bank of Fig. 5(a) with the world elevation map [Fig. 7(a)]. The results for four scales are shown in Fig. 7(b)–(e). Upon reconstruction using (20), we find that maxl,m | (x̂l,m − xl,m)/xl,m | = 1.3 × 10−6 for degrees between 15 to 79 inclusive. The reconstruction error obtained is expected since the quadratic penalty optimization method from the previous section is performed until [in (18)] is in the order of 10−6. The reconstruction errors can be made arbitrarily small by running the quadratic penalty method with increasingly higher weights on the invertibility constraints.

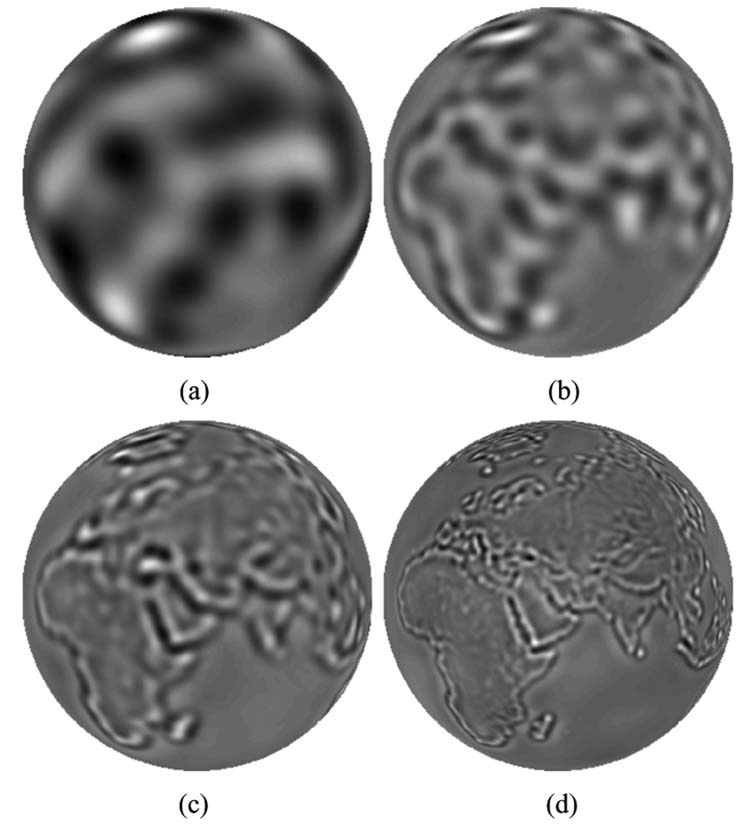

Fig. 7.

Outputs of the analysis filter bank of Fig. 5 applied to the world elevation map. Only four scales are shown. (a) Original Image. (b) a = 4. (c) a = 2. (d) a = 1. (e) a = 0.5.

To demonstrate that the optimization procedure is stable across different settings of parameters, we show a second example where we optimize for a four-scale wavelet filter bank (a = {4, 2, 1, 0, 5}. We enforce invertibility from degree 10 to 89 and apply a quadratic penalty on the magnitude of the combined frequency response for degrees above Lc = 150. The combined frequency response of the resultant filter bank is shown in Fig. 8(a). Once again, by varying the cutoff frequency threshold, we can obtain a tradeoff between ringing and sharpness of the cutoff [see Fig. 8(b)]. We apply the filter bank to the world elevation map [see Fig. 9] and find that invertibility is indeed obtained for degrees between 10 and 89 inclusive. Notice that there is significantly less ringing artifacts than in Fig. 7 as predicted by our measure of ringing at Lc = 150 [compare Fig. 6(b) and Fig. 8(b)].

Fig. 8.

(a) Combined frequency response of a four-scale wavelet filter bank obtained by our optimization procedure. a = {4, 2, 1, 0.5}. Invertibility is imposed from degree 10 to 89. Combined frequency response cutoff is set to Lc = 150. (b) Plot of ringing versus cutoff frequency Lc. (a) Combined frequency response, Lc = 150. (b) Ringing versus Lc.

Fig. 9.

Convolution outputs obtained by applying the analysis filter bank of Fig. 8(a) to the world elevation map of Fig. 7(a). Notice that there is less ringing artifacts than in Fig. 7 because ringing is lower in the four-scale filter bank than in the ten-scale filter bank when Lc is set to 150. (a) a = 4. (b) a = 2. (c) a = 1. (d) a = 0.5.

B. Spherical Steerable Pyramid

Just like the Euclidean domain [14], it can be shown that there is a direct tradeoff between angular resolution and steerability of oriented (nonaxisymmetric) filters on the sphere [29], i.e., filters that have higher angular resolving power requires a bigger set of “steering” basis filters. This can also be seen from Theorem 4.3. Filters with higher angular resolving power require spherical harmonics of higher orders, translating to more samples needed to satisfy the conditions of the generalized sampling theorem.

In our experiments, we limit our set of basis functions {Bi} to be the first two hundred spherical harmonics of order +1and −1. We note that we can increase our angular power by using higher orders, but this decreases the steerability of our filters. By considering only real filters, we can avoid working directly with the order −1 spherical harmonics, since their coefficients are effectively constrained by those of the order +1 spherical harmonics (see Appendix A). For convenience, we further constrain the coefficients of the order +1 spherical harmonics to be real.

We define the set of scales to be a = {2−n/2}, n = −4,…,4, with a = 1 corresponding to the undilated template. Once again, we use S2kit [15] to create a table of the spherical harmonic coefficients of for l = 1,…,200. We find the first 999 order 1 spherical harmonic coefficient of each dilated spherical harmonic (the order of a spherical function does not change under dilation). We verify that for a = 4 and a = 0.25, .

Similar to the previous subsection, we penalize the magnitude of the leading coefficients of ha=1(θ,ϕ). We also penalize the second derivatives of the filters’ frequency responses and spherical harmonic coefficients. Finally, we fix the amplitude scaling factors bk’s at all scales to be the same.

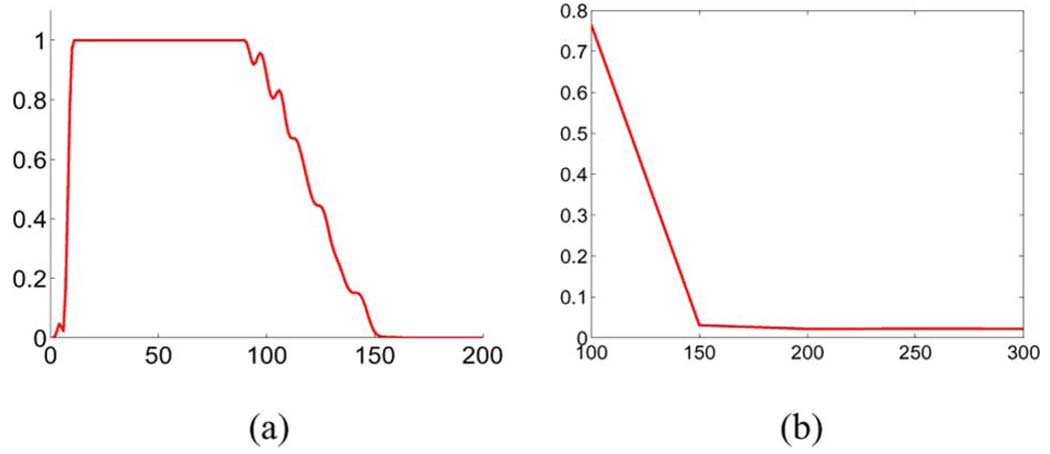

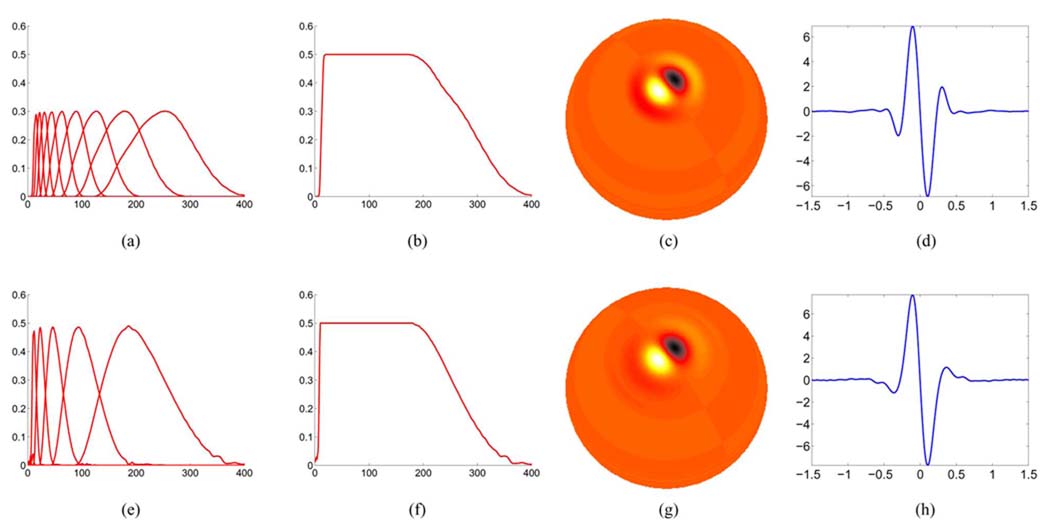

Fig. 10(a) and (b) illustrates the frequency response of a ninescale steerable pyramid ( a = {2−n/2}, n = −4,…4) obtained through our optimization procedure. Invertibility is enforced from degree 20 to 170. Note that the frequency response is equal to 0.5 in the invertibility range because we only plot the frequency response contributed by the order +1 harmonics. Fig. 10(c) shows ha=4(θ,ϕ) as a spherical image. Note that it looks like a derivative of Gaussian. We can also quantify ringing by plotting ha=4(θ,ϕ) as a function of θ while fixing ϕ to correspond to the great circle passing through the maxima and minima of the filter [Fig. 10(d)].

Fig. 10.

(a)–(d) Nine-scale steerable pyramid (a = {2−n/2}, n = −4; …, 4) obtained by imposing invertibility from degree 20 to 170. Note that the frequency response is equal to 0.5 in the invertibility range because we only plot the frequency response contributed by the order +1 harmonics. (e)–(h) Five-scale steerable pyramid (a = {4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25}) obtained by imposing invertibility from degree 10 to 180. Note that the frequency response is equal to 0.5 in the invertibility range because we only plot the frequency response contributed by the order +1 harmonics. (a) Individual frequency response. (b) Combined frequency response. (c) ha = 4 (θ; ϕ). (d) Plot of ha = 4 (θ; ϕ) (−1:5 ≤ θ ≤ 1.5 radian). (e) Individual frequency response. (f) Combined frequency response. (g) ha = 4 (θ ϕ). (h) Plot of ha = 4 (θ ϕ) (−1:5 ≤ θ ≤ 1.5 radian).

Similarly, Fig. 10(e)–(f) shows the frequency response of a five-scale steerable pyramid (a = {4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25}) obtained through our optimization procedure. Invertibility is enforced from degree 10 to 180. Fig. 10(g) shows ha=4(θ,ϕ) as a spherical image and Fig. 10(h) is a plot of ha=4(θ,ϕ) as a function of θ by fixing ϕ.

C. Denoising

We now employ the steerable pyramid from Fig. 10(e)–(f) in a denoising experiment. We emphasize that this toy example only serves to illustrate the use of the self-invertible steerable pyramid and is not meant to be the model on how wavelet or steerable pyramid denoising should be done. We first obtain a full pass steerable pyramid filter bank by computing a residual lowpass and highpass filter bank so that the combined filter bank is invertible up to degree 300. By constraining the analysis and synthesis filters to be identical and axisymmetric, the lowpass and highpass filters are uniquely determined.

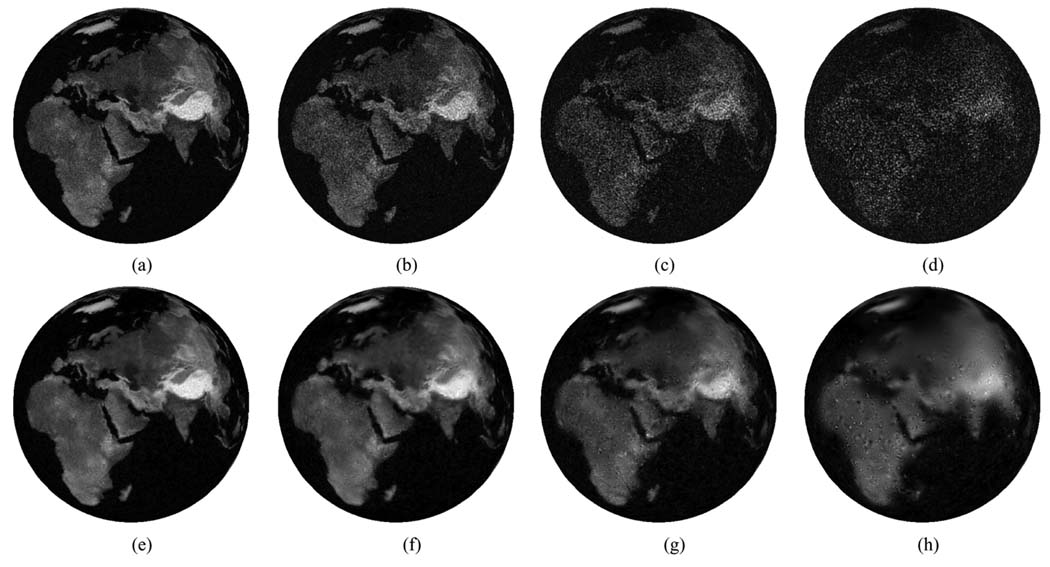

We use the world elevation map truncated to a maximum degree of 300. A Gaussian noise map is first produced in the spatial domain on the S2kit grid. The forward and inverse spherical harmonic transform is then performed with S2kit [15]. As noted earlier, the resulting noise image map from the inverse spherical harmonic transform will be different from the original noise map, because the fast spherical harmonic transform [11] is not invertible for nonbandlimited signals. Interestingly, noise near the poles tends to be suppressed under the forward and inverse spherical harmonic transform (not shown), possibly related to the concentration of samples near the poles on a latitude- longitude grid. The noise map obtained from the inverse spherical harmonic transform is then added to the world map. Fig. 11(a)–(d) display world elevation maps with different peak signal-to-noise ratios (PSNR).

Fig. 11.

(a)–(d) Corrupted world elevation maps. (e)–(h) Corresponding denoised world elevation maps, i.e., (e) shows the denoised version of (a), and so on. (a) PSNR = 27.923 dB. (b) PSNR = 21.943 dB. (c) PSNR = 15.9035 dB. (d) PSNR = 9.8804 dB. (e) PSNR = 31.578 dB. (f) PSNR = 27.74 dB. (g) PSNR = 24.16 dB. (h) PSNR = 21.0649 dB.

We adapt the wavelet shrinkage technique pioneered by Donoho and Johnstone [10] to our denoising problem.

We perform continuous spherical convolution between the noisy world elevation map and the analysis filters of the steerable pyramid using the algorithm in [28].

We sample the transform coefficients using the inverse FFT, by using the uniform sampling grid of the second quadrature rule (Appendix D) and the fact that the continuous spherical convolution in step 1 is computed by representing functions SO(3) as sum of complex exponentials.

- We threshold the sampled transform coefficients

where for brevity, we denote the sampled transform coefficients yn(αj,n,βs,n,γk,n) by ynjsk. The soft threshold (shrinkage) sets to zero for ynjsk below tσn in absolute value and pulls other data towards the origin by an amount tσn. The noise standard deviation σn can be determined empirically or by simulations [26]. In our toy example, we find that σn consistently doubles from one steerable pyramid scale to the finer one, except for the scale corresponding to the highpass filter. t is a user-defined parameter. In our experiments, we vary from t 0.5 to 5. We note that in the SureShrink [10] algorithm, the parameter t is found automatically once the noise standard deviation σn is known. Unfortunately, naive application of SureShrink gives poor results. One reason is that the coefficients of the overcomplete steerable pyramid is correlated, and, hence, the noise is no longer independently and identically distributed (i.i.d) in the steerable pyramid domain.(21) We utilize (6) and (7) to reconstruct the denoised image. Details of the computation are found in Appendix E.

Recall that Ln (On) is the maximum degree (order) of the nth synthesis filter (and the analysis filter since they are identical). Then, step 1 of the above procedure roughly requires computational complexity of . Step 2 requires O(Ln log Ln) computations. Step 3 requires computations. Step 4 is the bottleneck, requiring computations. We are currently working on faster algorithms and quadrature rules for step 4.

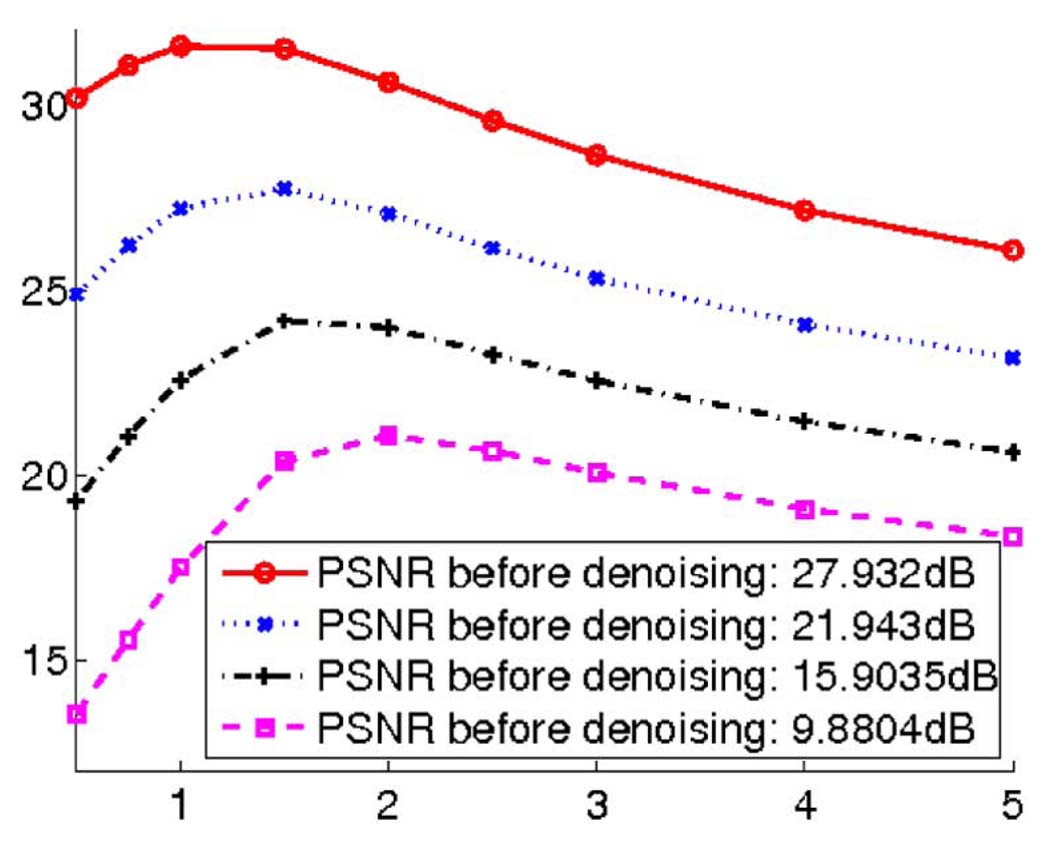

Fig. 12 shows a plot of the PSNR of the denoised images as we vary t from 0.5 to 5. In general, the noisier the image before denoising, the greater the improvement. In particular, there is an improvement of more than 10dB for the noisiest map. The best results are obtained for t between 1 and 2. The denoised maps corresponding to the best t’s are shown in Fig. 11(e)–(f). Artifacts become more noticeable for the noisier images. These artifacts are likely the by-products of ringing.

Fig. 12.

PSNR of denoised images as t is varied from 0.5 to 5.

VII. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this paper, we present theoretical conditions for the invertibility of filter banks under continuous convolution on the 2-Sphere. We discretize the results using quadrature, thus obtaining a generalized sampling theorem. We propose a general procedure for constructing invertible filter banks and demonstrate the procedure by generating self-invertible spherical wavelets and steerable pyramids. Finally, we provide an analysis of the computational complexity of the filtering framework.

Nonlinear dilation of functions on the sphere remains difficult to work with. While we circumvent the problem by using the distributive property of stereographic dilation, the spherical harmonic coefficients table can take up a substantial amount of space. More efficient methods are, therefore, needed. Other definitions of dilation (such as those defined in the frequency domain) might also fit better into the computational framework. More work is needed to understand the space of invertible and self-invertible filter banks. As seen in our experiments, there is an implicit tradeoff between the sharpness of the frequency response of the filters and ringing. It will be useful to formulate an objective function that directly trades off between ringing and the sharpness of the frequency response. The bandlimited spatially-concentrated eigenfunctions proposed by Simons et al. [24] could prove to be a useful set of basis functions for the optimization problem in our framework.

This paper introduces theoretical results on invertibility and sampling, and represents a step towards a general framework for filter design on the 2-Sphere. Just as wavelets and steerable pyramids have been useful for the processing and analysis of planar images, we are optimistic that future work will lead to similar applications on the sphere.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank M. Tappen for discussions on optimization procedures, B. Freeman and T. Adelson for discussions on self-invertibility, V. Goyal for discussions on norm preserving dilations in Euclidean wavelets and wavelet 7 denoising, and F. Durand and B. Horn for reading earlier drafts of this paper. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their many useful suggestions and pointers to references. T. Yeo would like to thank C.-L. Cheng for discussions on spherical harmonics and Wigner-D functions.

This work was supported in part by the National Alliance for Medical Image Analysis (NIH NIBIB NAMIC U54-EB005149), in part by the Neuroimaging Analysis Center (NIT CRR NAC P41-RR13218), in part by the Morphometry Biomedical Informatics Research Network (NIH NCRR mBIRN U24-RR021382), in part by the NIH Grant NINDS R01-NS051826, and in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant CAREER 0642971. B.T. T. Yeo was supported in part by the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research, Singapore. W. Ou was supported by the NSF graduate fellowship. The associate editor coordinating the review of this manuscript and approving it for publication was Prof. Ljubisa Stankovic.

Biographies

Boon Thye Thomas Yeo received the B.S. and M.S. degrees in electrical engineering from Stanford University, Stanford, CA, in 2002. He is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree in computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

His current research focuses on developing and applying techniques in signal processing, statistics, and differential geometry to the problems of registration, segmentation, and shape analysis in neuroimaging.

Mr. Yeo has received several awards, including the MICCAI Young Scientist Award, A * STAR National Science Scholarship, Frederick E. Terman Engineering Scholastic Award, and the Hewlett-Packard and Agilent Technologies Project Award.

Wanmei Ou received the B.S. degree in electrical engineering from the City College of the City University of New York (Salutatorian) in 2003, the M.S. degree in electrical engineering and computer science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, in 2005, where she is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree.

She is interested in developing mathematical algorithms to improve brain activity detection for functional brain studies, as well as to quantify difference in anatomical structures. Her research projects include spatial regularization for fMRI, spatio-temporal EEG/MEG inverse problems, neurovascular coupling, wavelets analysis, and joint analysis of fMRI and EEG/MEG data.

Polina Golland received the B.S. and M.S. degrees from the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, and the Ph.D. degree in 2001 from the Massachusetts Insitute of Technology (MIT), Cambrige.

She is an Assistant Professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department and the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT. She has worked on various problems in computer vision, including motion and stereo, shape modeling, and representation. Her current research focuses on modeling biological shape and function using images (from MRI to microscopy) as a source of information.

Prof. Golland has served on program committees of several leading conferences and as a referee for international journals in biomedical image analysis and computer vision. She received the NSF CAREER Award in 2007.

APPENDIX A

SPHERICAL HARMONICS BASICS

Here, we review useful facts on the spherical harmonics.

Spherical Harmonics

The spherical harmonics are defined in terms of the associated Legendre polynomials . For a given degree l ≥ 0 and order |m| ≤ l, 0 ≤ θ ≤ π, and 0 ≤ ϕ ≤ 2π

| (22) |

where, for m ≥ 0 and |x| < 1

| (23) |

| (24) |

Therefore, for l ≥ m ≥ 0, we have

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

Rotation of Spherical Harmonics on the Sphere

Under rotation, each spherical harmonic of degree l is transformed into a linear combination of spherical harmonics of the same degree but possibly different orders. In particular, if we parametrize our rotation by the three Euler angles, α, β, γ, and rotate our original function f, it can be shown that

| (28) |

where is the Wigner-D function [20]. We can further decompose as follows:

| (29) |

where is the Wigner-d function and is real [20]

| (30) |

The sum is over all j such that none of the denominator terms with factorials is negative. This reflects the fact that only rotations about the y-axis mixes orders.

By the Peter–Weyl theorem on compact groups [30]

| (31) |

By integrating out α and γ, we obtain

| (32) |

We will also use the identity [28]

| (33) |

APPENDIX B

PROOF OF CONTINUOUS-INVERTIBILITY

Here, we prove Theorem 4.1 on continuous frequency response. We first note that by using Parseval’s Theorem and substituting (28), we can re-write the output of the nth analysis filter as

| (34) |

| (35) |

and the reconstructed image as

| (36) |

| (37) |

Projecting x̂(θ,ϕ) onto the spherical harmonics basis, we obtain

| (38) |

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

APPENDIX C

PROOF OF DISCRETE-INVERTIBILITY

Here, we prove the generalized sampling theorem. Recall from Section III that yn(αj,n,βs,n,γk,n) are samples of yn(α,β,γ) and that L̃n (Õn) and Ln (On) and are the highest nonzero harmonic degree (order) of h̃n and hn, respectively.

Since the output of the nth synthesis filter x̃n (θ, ϕ) is a linear combination of rotated versions of hn(θ,ϕ) (7), for l > Ln, and we obtain the trivial result

| (43) |

We will now show that for l ≤ Ln

| (44) |

From (35)

| (45) |

| (46) |

| (47) |

| (48) |

| (49) |

For wj,s,k,n = 4π2ws,n/(JnKn) (as required by the theorem), the output of the nth synthesis filter becomes (46) and (47), shown at the bottom of the page. Projecting x̂n(θ,ϕ) onto the spherical harmonics, for l ≤ Ln (and, thus, |m| ≤ Ln), we have (48) and (49), shown at the bottom of the next page, where we have arranged the terms so that they look like the setup for Peter–Weyl Theorem, except we have summations instead of integrals. Let Φ be the last part of (49), and, thus, we have

| (50) |

To simplify Φ, we write

| (51) |

| (52) |

We note that and |m′| ≤ l′ ≤ L̃n |m| ≤ Ln and, therefore, −L̃n − Ln ≤ m′ − m ≤ L̃n + Ln. Since αj,n = 2πj/(L̃n + Ln + 1), j = 0, 1,…,L̃n + Ln, we can conclude via the geometric series that

| (53) |

Similarly, from (48), we observe that |m′| ≤ Oh̃n and |m‴| ≤ On. Using the same reasoning, we get

| (54) |

Substituting into (52), we get

| (55) |

| (56) |

| (57) |

| (58) |

where in the third equality, m‴ = m″, m′ = m because of the delta functions, and the last equality was obtained using the assumption that wsn and βs,n are the quadrature weights and knots of the integral . We can now substitute (58) back into (50)

| (59) |

| (60) |

| (61) |

thus proving (44). Together with (43), we have

| (62) |

APPENDIX D

QUADRATURE RULES

In this appendix, we derive two different quadrature rules that satisfy the conditions of Theorem 4.3, namely, we show quadrature weights ws,n and knots βs,n, such that for l ≤ Ln, l′ ≤ L̃n

| (63) |

Quadrature Rule (1)

We denote and observe that f(β) consists of a linear combination of even powers of cos(β/2) and sin(β/2) (see (30)). Therefore, if we make the substitution u = sin(β/2), and noting that f(u) (where we are overloading f) is now a polynomial with maximum degree, Q = 2(l + l′) ≤ 2 (Ln + L̃n), we get

| (64) |

Now, making the substitution, υ = 2u − 1, we have

| (65) |

where rk’s are defined to be the weights of the Gauss–Legendre quadrature on the interval [−1,1], and υk’s correspond to the sampling knots [19]. The weights and abscissas can be found by standard algorithms (see for example [19]). In general, quadrature integration is exact up to polynomial powers 2N − 1 where N is the number of samples. Because the integrand’s highest polynomial power is Q+1, if N ≥ Q/2+1 (or N ≥ [Q/2]+1), then 2N − 1 ≥ Q+1, and, thus, the quadrature formula is exact.

From the substitution above, we have sin βk/2 = uk = (υk + 1)/2 or βk = 2 sin−1 (υk + 1)/2). In conclusion, for N = [Q/2] + 1, we have, and , where ws = rs (υs + 1) and βs = 2 sin−1 ((υs + 1)/2), where rs and υs are the quadrature weights and knots of the Gauss–Legendre quadrature.

Quadrature Rule 2

We will derive another rule in this section, using the technique shown in [11]. However, first we need to obtain the Fourier series formula for the square wave, SQ(u), which is defined to be periodic from −π to π

| (66) |

Projecting SQ(u) onto the Fourier series basis, we get

| (67) |

| (68) |

| (69) |

| (70) |

| (71) |

If k = 4n, we get 2 cos(2nπ) − 1 − cos(4nπ) = 0

If k = 4n + 1, we get 2 cos(2nπ + π/2) − 1 − cos (4nπ + π) = 0

If k = 4n + 2, we get 2 cos(2nπ + π) − 1 −cos(4nπ + 2π) = −4

If k = 4n + 3, we get 2 cos(2nπ + 3π/2) − 1 − cos(4nπ + 3π) = 0.

Therefore, the Fourier series for SQ(u) is nonzero for k = 4n+2, and is equal to −4i/πk, and we have

| (72) |

Now, we can continue with the derivation of the quadrature. We note that f(β) = ∑k,k′ak cos(β/2)k sin (β/2)k′), where k and k′ are always even, non-negative and bounded (once again, we are overloading f). We can express them as complex exponentials so that f(β) = ∑q bq(eiβ/2)q where q can take on negative values, but it is still bounded: |q| ≤ 2(l + l′) ≤ 2(Ln + L̃n). Note that if we make the substitution β′ = β/2, we now have f(β′) = ∑k,k′ ak cos(β′)k sin(β′)k′ = ∑q bq (eiβ′)q. Therefore

| (73) |

| (74) |

| (75) |

where the middle equality was obtained using symmetry arguments since f is a linear combination of even positive powers of sin and cos.

Since |q| ≤ Q implies that the term f(β′) sin(2β′) has exponential powers ≤ Q + 2, we can eliminate terms in the Fourier series of SQ(β′) that falls out of the range (by orthonormality of the exponentials), thus we only require p such that

| (76) |

| (77) |

| (78) |

| (79) |

Defining , we have

| (80) |

| (81) |

Let us define the highest exponential power to be B and notice that B = Q + 2 + 4⌊Q/4⌋ + 2 = Q + 4⌊Q/4⌋ + 4, while lowest exponential power corresponds to −Q −2 −4⌊Q/4⌋ − 2 = −Q − 4⌊Q/4⌋ = −B. Let N be the smallest integer such that B < 4N, where N is an integer. Therefore, N = ⌊Q/4⌋ + ⌊Q/4⌋ + 1 + 1 = 2⌊Q/4⌋ + 2

It is easy to verify the following identity:

| (82) |

Substituting the identity into (81), we get β′ → 2πk/(4N)); see (83)–(87), shown at the bottom of the page, where the second

| (83) |

| (84) |

| (85) |

| (86) |

| (87) |

last equality uses the fact that sin(−2π) = 0 and the function f is even, and the last equality uses the fact that sin π = 0 and f(β′) is even about β′ = π. Because , hence βk = πk/N for k = 0, 1,…N − 1 corresponds to our quadrature knots, with quadrature weights, .

Summary

We have formulated two possible ways of obtaining an exact quadrature of and the integral is equal to if we select the correct samples and corresponding weights. In particular, this is true for:

- βs = 2 sin −1((υs + 1 and ws = rs(υs + 1), s = 0, 1,…N −1, where:

- N = [Q/2] + 1;

- Q is the highest power of when viewed as a polynomial in sin(β/2);

- rs and υs are the weights and nodes of the Gaussian-Lengendre quadrature on the interval [−1, 1].

- βs = πs/N and , s = 0, 1,…N − 1, where:

- N = 2⌊Q/4⌋ + 2;

- Q is the highest power of when viewed as a polynomial in e(iβ/2).

Note that Q = 2(l + l′) ≤ 2(Ln + L̃n). The second set of quadrature knots is similar to that used in the fast Wigner-D transform (SOFT) [16], except that the north pole (s = 0) is removed from the SOFT discretization.

APPENDIX E

INVERSE CONVOLUTION WITH NON-AXISYMMETRIC FILTERS

For brevity, we denote yn(αj,n, βs,n, γk,n) by ynjsk. Given ynjsk, one can compute x̂n (θ,ϕ) by rewriting (6) and computing its spherical harmonics

| (88) |

Since

| (89) |

for a particular (αj,n, βs,n, γk,n), we can compute [D(αj,n, βs,n, γk,n)hn]l,m for all degrees l and orders m with O(L3On)computations. This can be done by computing and storing in advance.

Recall that Ln(On) is the maximum degree (order) of the nth synthesis filter (and the analysis filter since they are identical). Since Jn = O(Ln)Sn = O(Ln) and Kn = O(On), the brute force method of computing for all degrees and orders yields a algorithm.

However, a faster algorithm can be achieved.

for all l, m.

- For each βs and γk:

- compute [D(0,βs,n, γk,n)hn]l,m for all l, m;

- for each αj,n:

- compute [D(0, 0,αj,n)D(0, αs,n,γk,n)hn]l,m for all l, m;

.

Since step 2a dominates step 2b, the runtime complexity is .

Footnotes

We note that the symbol D is overloaded to imply rotation as well as dilation, but the meaning should be clear depending on the context.

We note that the approach commonly used with planar images of applying a constant filter to a subsampled image fails here because the sphere is periodic and bounded, causing the effective size of the image features (relative to the filter) to stay constant with subsampling. We also note that nonlinear dilation is necessary since the sphere is compact, hence dilating a spherical function by naively scaling the radial component of the spherical function, f(θ ϕ) → f((θ/a);ϕ), leads to undesirable “wrap-around” effects.

We use the matlab interface from the publicly available Yet Another Wavelet Toolbox (YAWTb): http://rhea.tele.ucl.ac.be/yawtb/

Color versions of one or more of the figures in this paper are available online at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org.

Contributor Information

Boon Thye Thomas Yeo, Email: ythomas@csail.mit.edu.

Wanmei Ou, Email: wanmei@csail.mit.edu.

Polina Golland, Email: polina@csail.mit.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoine J-P, Vandergheynst P. Wavelets on the 2-Sphere: A Group-theoretical approach. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 1999;vol. 7:262–291. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage C, Wandelt BD. Deconvolution map-making for cosmic microwave background observations. Phys. Rev. D 70. 2004;vol. 123007:123013–123013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertsekas DP. Nonlinear Programming. Nashua, NH: Athena Scientific; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdanova I, Vandergheynst P, Antoine J-P, Jacques L, Morvidone M. Stereographic wavelet frames on the sphere. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2005;vol. 19:223–252. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brechbuhler CH, Gerig G, Kubler O. Parametrization of closed surfaces for 3-D shape description. Comput. Vis. Image Understand. 1994;vol. 61(no 2):154–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooley JW, Tukey JW. An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex Fourier series. Math. Comput. 1965;vol. 19(no 90):297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daubechies I. Ten lectures on wavelets. SIAM. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demanet L, Vandergheynst P. Gabor wavelets on the sphere. Proc. SPIE. 2003;vol. 5207:208–215. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do MN, Vetterli M. The finite ridgelet transform for image representation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2003 Jan;vol. 12(no 1):16–28. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2002.806252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donoho DL, Johnstone IM. Adapting to unknown smoothness via wavelet shrinkage. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1995;vol. 90(no 432):1200–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driscoll JR, Healy DM. Computing Fourier transforms and convolutions on the 2-Sphere. Adv. Appl. Math. 1994;vol. 15:202–250. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeden W, Windheuser U. Spherical wavelet transform and its discretization. Adv. Comput. Math. 1996;vol. 5:51–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeden W, Gervens T, Schneider M. Constructive Approximation on the Sphere: With Applications to Geomathematics. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman WT, Adelson EW. The design and use of steerable filters. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1991 Sep;vol. 13(no 9):891–906. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostelec PJ, Rockmore DN. A Lite Version of Spharmonic Kit. [Online]. Available: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/geelong/sphere/

- 16.Kostelec PJ, Rockmore DN. Ffts on the rotation group. Proc. Santa Fe Institute Working Papers Series Paper 03-11-060. 2003 [Online]. Available http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/geelong/

- 17.Mhaskar HN, Narcowich FJ, Prestin J, Ward JD. Polynomial frames on the sphere. Adv. Comput. Math. 2000;vol. 13:387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papoulis A. Generalized sampling expansion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 1977 Nov;vol. 24(no 11):652–654. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical Recipes in C: The Art of Scientific Computing. 2nd ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurai JJ. Modern Quantum Mechanics. 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroder P, Sweldens W. Spherical wavelets: Efficiently representing functions on the sphere; Proc. SIGGRAPH; 1995. pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroder P, Sweldens W. Spherical wavelets: Texture processing. Rendering Tech. 1995 Aug;:252–263. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simoncelli EP, Freeman WT, Adelson EH, Heeger DJ. Shiftable multi-scale transforms. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 1992 Feb;vol. 38(no 2):587–607. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons F, Dahlen F, Wieczorek M. Spatiospectral concentration on a sphere. SIAM Rev. 2006;vol. 48(no 3):504–536. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starck J-L, Candes EJ, Donoho DL. The curvelet transform for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2002 Jun;vol. 11(no 6):670–684. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2002.1014998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starck J-L, Moudden Y, Abrial P, Nguyen MK. Wavelets, ridgelets and curvelets on the sphere. Astron. Astrophys. 2006;vol. 446:1191–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vetterli M, Kovačevic J. Wavelets and Subband Coding. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wandelt BD, Gorski KM. Fast convolution on the sphere. Phys. Rev. D 63. 2001;vol. 1230002:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiaux Y, Jacques L, Vandergheynst P. Correspondence principle between spherical and Euclidean wavelets. Astrophys. J. 2005;vol. 632:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiaux Y, Jacques L, Vandergheynst P. Fast directional correlation on the sphere with steerable filters. Astrophys. J. 2006;vol. 652:820–832. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeo BTT, Ou W, Golland P. Invertible filter banks on the 2-Sphere. Proc. Int. Conf. Image Processing; 2006. pp. 2161–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu P, Grant PE, Qi Y, Han X, Segonne F, Pienaar R, Busa E, Pacheco J, Makris N, Buckner R, Golland P, Fischl B. Cortical surface shape analysis based on spherical wavelets. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2007 Apr;vol. 26(no 4):582–598. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.892499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu P, Yeo BTT, Grant E, Fischl B, Golland P. Cortical folding development study based on over-complete spherical wavelets. presented at the IEEE Computer Society Workshop on Mathematical Methods in Biomedical Image Analysis; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]