Abstract

The rat basolateral amygdala shows neuroanatomical sex differences, continuing development after puberty and aging-related alterations. Implications for amygdala-dependent memory processes were explored here by testing male and female hooded rats in adolescence, adulthood and old age on the food-conditioned place preference task. While aged rats were unimpaired, adolescents failed to learn the task. This finding may be related to ongoing development of the basolateral amygdala and related memory systems during the adolescent period.

Keywords: Learning, Memory, Development, Aging, Sex differences, Basolateral amygdala

The basolateral amygdala (BLA) is critical to the modulation of learning and memory under high emotional salience and mediates several emotional learning tasks, both positive and aversive [1,24,28]. Amygdalar structural and functional abnormalities accompany a number of psychopathologies such as depression, schizophrenia, autism, and Alzheimer’s disease, all of which are sexually dimorphic in incidence and/or presentation and most of which are age-sensitive in time of onset [4,13,50]. In rats, reports of sex differences in BLA structure and physiology include spine density [38], number of GABAergic neurons [44], and neurotransmitter release [30]. Furthermore, the effects of stress on learning and memory, mediated by the BLA [36], interact strongly with sex and sex hormones [6,37,49,52]. Yet, the limited number of studies which have directly compared performance of male and female rats in the BLA-dependent fear conditioning task [25,35] report inconsistent results.

Both adolescence and aging may also influence BLA function. In human imaging studies, patterns of amygdalar activity change between adolescence and adulthood [31], and there are sexual dimorphisms in both functional [22] and structural [18] patterns of development. In rodents, where effects can be examined at the level of different amygdalar nuclear groups, increases in acetylcholinesterase activity [5], and decreases in the number of neurons and glia of the BLA [39] are among alterations observed to continue after puberty. Aging is likewise accompanied by a number of anatomical and electrophysiological alterations in rodents [2,38,48], but the functional significance of these changes is not clear. Results from studies related to BLA function in aged rodents are mixed [19,32], as are results from similar studies of human amygdalar function in old age [10,15], with evidence both for preserved and compromised function.

The present study explores potential functional implications of sex, adolescence, and aging-related anatomical changes in the BLA by comparing performance of a BLA-dependent memory task in intact rats of both sexes at three different ages. The food-conditioned place preference (CPP) task was chosen as an investigative tool since it does not depend on the use of a major stress component (such as foot shock), which given the interactions of stress with both sex and age [21] would create interpretive confounds. The CPP task has been frequently used as a tool to explore BLA-dependent memory [17,26,27,42] since it was demonstrated that memory for the reinforcer is needed for performance [51] and that task performance depends on nuclei of the BLA [14,20,41].

Subjects were Long-Evans hooded rats of both sexes at one of three ages: peri-adolescence (35–36 days old at testing; 10 males, 9 females), young adulthood (3–5 months; 12 males, 10 females), and old age (18–21 months; 11 males, 9 females). The adolescent and adults groups were born in the animal colony of the Psychology Department at the University of Illinois, from stock originally obtained from Simonsen Laboratory (Gilroy, CA), and were weaned at day 25. The aged animals were acquired as adults from Simonsen and used as breeders until 10–12 months of age. All rats were housed in clear Plexiglas cages, in a temperature-controlled environment in the Psychology Department colony on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle (lights on at 08:00 h). The rats were pair- or triple-housed and food and water were available ad libitum. When food deprivation began the rats were housed singly. All the rats were handled weekly until food deprivation was begun, when they were handled daily until the end of the experiment. Animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adults and aged rats were food-deprived to 90% of initial, free-feeding weight over 7–9 days prior to the beginning of training, and maintained at that weight throughout training. Newly weaned pups were food deprived to 90% of targeted weight as judged from age matched controls, beginning 3–5 days prior to training. During food deprivation, 2–3 Froot Loops™ were introduced along with the daily ration of rat chow.

The CPP apparatus was built to the dimensions described in other studies that have demonstrated nuclei of the BLA were critical to acquisition and/or expression in this task [20,41,42]. The Plexiglas apparatus, situated on an opaque table approximately four feet above the floor, consisted of two large, adjacent compartments (each 45 cm × 45 cm × 30 cm high), and a smaller compartment (36 cm × 18 cm × 20 cm high) connecting them, which was centered along the length of the two main compartments. The apparatus was opaque except for the ceiling and the small connecting compartment, which allowed for observation. Made of transparent, smoked Plexiglas, the small compartment could be opened from the front, so that a rat could be placed inside with access to both large compartments. During training a black Plexiglas divider was inserted to confine the subject to a single large compartment. The floor and ceiling of the apparatus were made of clear Plexiglas; the ceiling contained numerous large, evenly spaced air-holes.

The walls of one of the large compartments were black and the walls of the other were white. The large compartments differed in two other sensory dimensions: the floor of the white compartment was covered with a novel corn cob bedding, and the black compartment was paired with a cinnamon oil scent, applied to a small square (2 cm2) of paperboard taped to the wall. Each of the large compartments contained a round porcelain cup (diameter 7 cm), in which 50 Froot Loops™ were placed during training.

Habituation, training, and testing took place over eight consecutive days in the afternoon, and followed the general procedures in the literature [20,41,42]. Habituation took place on day 1, when the rats were placed in the alleyway and given free access to the entire apparatus for a 10-min period, while time spent in each of the two large compartments was recorded. A rat was considered to be in a compartment when both of its forepaws were in it. Training sessions took place over 6 days (days 2–7), when rats were confined to the black and white compartments on alternate days for 30-min sessions. During training, a randomly determined half of the rats in each group received 50 Froot Loops™ when in the black compartment, and half when in the white compartment. Half the rats began training in the food-paired compartment (days 2, 4, and 6) and half received food on days 3, 5, and 7. The apparatus was cleaned and disinfected with Novalsan solution between subjects. Daily feeding was delayed for at least 1 h post-training to eliminate mnemonic effects of the rat chow [16]. Day 8 consisted of testing, in which each rat was given free access to the whole apparatus for 20 min and time in each compartment was recorded. In addition, first compartment choice and behavior in the first 10 min were recorded at test for all but three (one male, two female) aged subjects.

There were no differences in time spent in the black versus white compartments during habituation in any of the groups, indicating the apparatus was unbiased. A test for correlation between number of Froot Loops™ eaten during training sessions and difference scores (time in previously paired – time in unpaired compartment at test) indicated no relationship between amount eaten and performance, when analyzed across all subjects and within age and sex groups. As a proportion of body weight, the average number of Froot Loops™ eaten in a training session was highest for adult rats (0.106), followed by adolescents (0.064), and aged rats (0.048).

Planned comparisons were used to examine age and sex effects on adolescent versus adult rats, and adult versus aged rats, as we did not view comparisons between adolescents and the aged as meaningful. Two factor (sex and age) ANOVAs with a repeated measure of compartment (paired and unpaired) were run to compare conditioning across these groups.

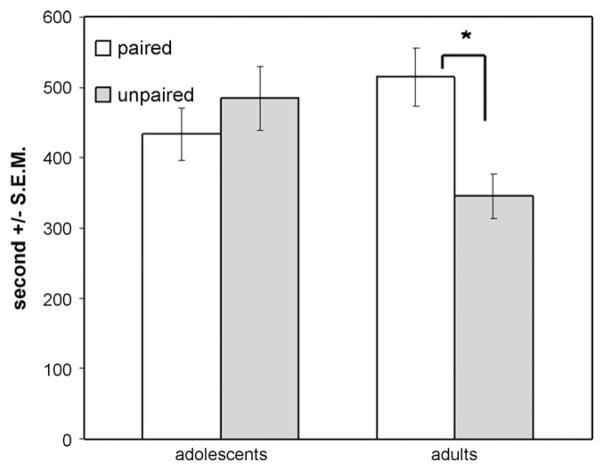

The adolescent/adult comparison indicated an age by compartment interaction [F(1, 37) = 4.268, p = 0.046]. Sex did not interact with compartment and there was no sex by age by compartment interaction. Post hoc two-tailed paired t-tests were used to explore the compartment by age interaction. Adult rats spent significantly more time in the previously paired versus unpaired side [t(21) = 2.454, p = 0.023], while the adolescents failed to show a compartment preference (Fig. 1). Analysis limited to the first 10 min of testing yielded similar results, with the age by compartment interaction reaching significance [F(1, 37) = 9.515, p = 0.004], but no effect of sex. Post hoc two-tailed paired t-tests indicated that adults spent more time in the previously paired compartment in the first 10 min of testing [t(21) = 3.440, p = 0.002] while adolescents did not. Chi-square analysis indicated first compartment entry (paired versus unpaired) did not differ from chance or as a function of sex or age.

Fig. 1.

Time spent in previously food-paired and -unpaired compartments during testing session. Adults spent significantly more time in the previously food-paired compartment, while adolescents did not discriminate. *p < 0.03.

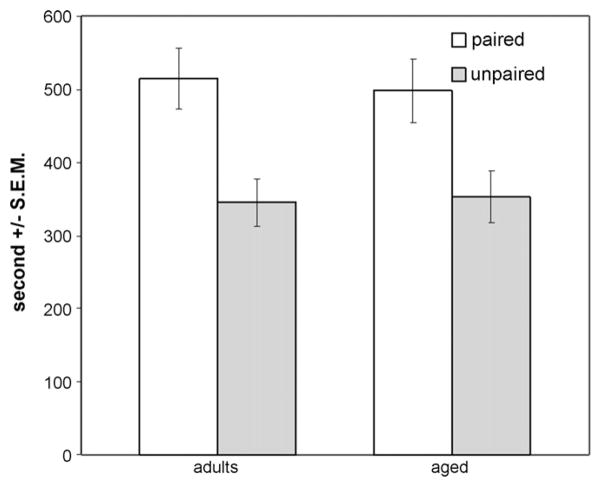

In the ANOVA comparing adults and aged, there were no interactions of any factor with compartment. The within-factor of compartment was significant [F(1, 39) = 9.527, p = 0.004], indicating all subjects learned the task (Fig. 2). Analysis of performance in the first 10 min of testing was used to compare the adult subjects with the 18 aged subjects for which this data was available. As in the entire 20-min testing period, aged and adult subjects overall exhibited significant preference for the paired compartment within the first 10 min [F(1, 36) = 12.993, p = 0.001]. Sex did not interact with compartment or age. Thus, as with the adolescent/adult comparison, behavior in the first 10 min of testing yielded qualitatively identical results yet stronger effects. Chi-square analysis indicated no difference in first compartment entry from chance levels and no difference in this measure by sex or age.

Fig. 2.

Time spent in previously food-paired and -unpaired compartments by adult and aged groups during test session. Both groups spent more time in the previously food-paired compartments (p < 0.005).

Three main findings emerged from this study using food-based CPP: (1) adolescents failed to learn this task after a period of training sufficient for adult learning, (2) performance was unaffected by sex, and (3) performance was preserved with age.

The BLA undergoes continuing development in adolescence [5,9,39]. For example, the basolateral nucleus loses 13% of both neurons and glia between adolescence and adulthood [39], and cholinergic innervation of the BLA does not reach adult levels until day 60 [5]. The latter may have particular implications for CPP performance, as direct intra-BLA infusions of the acetylcholine receptor antagonist scopolamine impair memory of adult rats in the food-CPP task, in an essentially identical task protocol to that used here [42]. However, the failure of adolescents to learn this task might also be related to the ongoing developmental processes in other memory systems which are involved in CPP (for review see Ref. [47]); for example the nucleus accumbens, like the BLA, is particularly implicated in food-based CPP [14], and peri-adolescent refinement of dopamine receptors in this structure [3] may contribute to the performance deficits observed in the adolescent group.

Another possibility is that the apparent failure by the adolescents to learn is more related to different motivational, rather than mnemonic, responses of adolescents [34,43]. Indeed, adolescent rats can learn versions of the CPP task using rewards other than food, including nicotine [46], alcohol [33], and cocaine and morphine [7], and perform as well as adults on the BLA-dependent fear conditioning task [23]. However, several facts suggest that motivational differences do not provide a clear explanation of these data. First, despite the lack of a place preference in the adolescent rats, this group ate more during training as a proportion of their body weight than did the aged rats, which did exhibit place preference. Second, unlike results from several CPP studies which examined the rewarding effects of a variety of drugs with adolescent and/or adult subjects of both sexes [8,29,40], we observed no sex differences in conditioning at any age. Finally, a study finding that adolescents are able to learn CPP with a novel-object reward [11] would seem to rule out an interpretation that food-, as compared to drug-reward, is not sufficiently salient to adolescent rats. That study, which investigated the performance of adolescent and adult rats of both sexes in either social or isolated housing conditions, found interactions among all three factors, with some adolescent groups displaying place preference [11]. Because rats were housed alone during this study and were weaned several days later than those in the novel-object study, comparison is difficult. (Another obstacle to comparison is that adolescents in the novel-object CPP study were trained in a small apparatus, built to parallel the scale of adult rats in their apparatus [11], suggesting the possibility of a difference in task difficulty.) Taken together, these facts indicate that motivational differences cannot wholly explain the present data. It appears that adolescents are capable of performing some forms of CPP but their performance is more easily disrupted than that of mature animals.

The other findings of interest here were the lack of sex differences and the preserved performance of aged rats. While high levels of estradiol impair food-CPP performance in ovariectomized females [17], there is little direct evidence for sex differences in performance of BLA-mediated tasks. The literature on BLA function in aged rodents, on the other hand, is suggestive of preserved function ([12,32,45] but see Ref. [19]). Indeed, we have found that neuron number is preserved in the basolateral nucleus of the aged rat [39] and that aged rats have a larger dendritic tree [38] and a greater number of glial cells [39] than young adults. Thus, the rat BLA undergoes different anatomical changes during adolescence versus between adulthood and old age, with adolescence accompanied by functional changes in some measures and aging relatively robust in resistance to cognitive alterations associated with BLA function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AG022499 and AA017354. MJR was supported by HD07333.

References

- 1.Aggleton JP. The contribution of the amygdala to normal and abnormal emotional states. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:328–33. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almaguer W, Estupinan B, Uwe Frey J, Bergado JA. Aging impairs amygdala–hippocampus interactions involved in hippocampal LTP. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:319–24. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. NeuroReport. 1997;8:1495–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron-Cohen S, Knickmeyer RC, Belmonte MK. Sex differences in the brain: implications for explaining autism. Science. 2005;310:819–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1115455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berdel B, Moryś J, Maciejewska B, Narkiewicz O. Acetylcholinesterase activity as a marker of maturation of the basolateral complex of the amygdaloid body in the rat. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1996;14:543–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman RE, Ferguson D, Luine VN. Effects of chronic restraint stress and estradiol on open field activity, spatial memory, and monoaminergic neurotransmitters in ovariectomized rats. Neuroscience. 2002;113:401–10. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JO, Wood RD, Spear LP. Cocaine and morphine-induced place conditioning in adolescent and adult rats. Physiol Behav. 2000;68:487–93. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Circulli F, Laviola G. Paradoxical effects of D-amphetamine in infant and adolescent mice: role of gender and environmental risk factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM. Amygdalo-cortical sprouting continues into early adulthood: implications for the development of normal and abnormal function during adolescence. J Comp Neurol. 2002;453:116–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denburg NL, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Adolphs R. Evidence for preserved emotional memory in normal older persons. Emotion. 2003;3:239–53. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Novel-object place conditioning in adolescent and adult male and female rats: effect of social isolation. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyere V, Gisquet-Verrier P, de Marsanich B, Ammassari-Teule M. Age-related modifications of contextual information processing in rats: role of emotional reactivity, arousal and testing procedure. Behav Brain Res. 2000;114:153–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drevets WC. Prefrontal cortical-amygdalar metabolism in major depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:614–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everitt BJ, Morris KA, O’Brien A, Robbins TW. The basolateral amygdala-ventral striatal system and conditioned place preference: further evidence of limbic–striatal interactions underlying reward-related processes. Neuroscience. 1991;42:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90145-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer H, Sandblom J, Gavazzeni J, Fransson P, Wright CI, Bäckman L. Age-differential patterns of brain activation during perception of angry faces. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flood JF, Smith GE, Morley JE. Modulation of memory processing by cholecystokinin: dependence on the vagus nerve. Science. 1987;236:832–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3576201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galea LAM, Wide JK, Paine TA, Holmes MM, Ormerod BK, Floresco SB. High levels of estradiol disrupt conditioned place preference learning, stimulus response learning and reference memory but have limited effects on working memory. Behav Brain Res. 2001;126:115–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giedd JN, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Kaysen D, et al. Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: ages 4–18 years. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366:223–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960304)366:2<223::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould TJ, Feiro OR. Age-related deficits in the retention of memories for cued fear conditioning are reversed by galantamine treatment. Behav Brain Res. 2005;165:160–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiroi N, White NM. The lateral nucleus of the amygdala mediates expression of the amphetamine-produced place preference. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2107–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-02107.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juraska JM, Rubinow MJ. Hormones and memory. In: Byrne J, Eichenbaum H, editors. Learning and memory: a comprehensive reference. Vol. 3. London: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 503–20. Memory systems. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killgore WD, Oki M, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Sex-specific developmental changes in amygdala responses to affective faces. Neuroreport. 2001;12:427–33. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Land C, Spear NE. Fear conditioning is impaired in adult rats by ethanol doses that do not affect periadolescents. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeDoux J. The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:727–38. doi: 10.1023/A:1025048802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maren S, De Oca B, Fanselow MS. Sex differences in hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: positive correlation between LTP and contextual learning. Brain Res. 1994;661:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald RJ, White NM. A triple dissociation of memory systems: hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:3–22. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McIntyre CK, Ragozzino ME, Gold PE. Intra-amygdala infusions of scopolamine impair performancd on a conditioned place preference task but not a spatial radial maze task. Behav Brain Res. 1998;95:219–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGaugh JL. The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meehan SM, Schechter MD. LSD produces conditioned place preference in male but not female fawn hooded rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitsushima D, Yamada K, Takase K, Funabashi T, Kimura F. Sex differences in the basolateral amygdala: the extracellular levels of serotonin and dopamine, and their responses to restraint stress in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:3245–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monk CS, McClure EB, Nelson EE, Zarahn E, Bilder RM, Leibenluft E, et al. Adolescent immaturity in attention-related brain engagement to emotional facial expressions. Neuroimage. 2003;20:420–8. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oler JA, Markus EJ. Age-related deficits on the radial maze and in fear conditioning: hippocampal processing and consolidation. Hippocampus. 1998;8:402–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<402::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philpot RM, Badanich KA, Kirstein CL. Place conditioning: age-related changes in the rewarding and aversive effects of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:593–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060530.71596.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Primus RJ, Kellogg CK. Pubertal-related changes influence the development of environment-related social interaction in the male rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1989;22:633–43. doi: 10.1002/dev.420220608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pryce CR, Lehmann J, Feldon J. Effect of sex on fear conditioning is similar for context and discrete CS in Wistar. Lewis and Fischer rat strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:753–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roozendaal B, Griffith QK, Buranday J, De Quervain DJ, McGaugh JL. The hippocampus mediates glucocorticoid-induced impairment of spatial memory retrieval: dependence on the basolateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1328–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337480100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubinow MJ, Arseneau LM, Beverly JL, Juraska JM. Effect of the estrous cycle on water maze acquisition depends on the temperature of the water. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:863–8. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubinow MJ, Drogos LL, Juraska JM. Age-related dendritic hypertrophy and sexual dimorphism in rat basolateral amygdala. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubinow MJ, Juraska JM. Neuron and glia numbers in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala from pre-weaning through old age in male and female rats: a stereological study. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:717–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.21924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russo SJ, Jenab S, Fabian SJ, Festa ED, Kemen LM, Quinones-Jenab V. Sex difference in the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. Brain Res. 2003;970:214–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder JP, Packard MG. Differential effects of intra-amygdala lidocaine infusion on memory consolidation and expression of a food conditioned place preference. Psychobiology. 2000;28:486–91. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeder JP, Packard MG. Posttraining intra-basolateral amygdala scopolamine impairs food- and amphetamine-induced conditioned place preferences. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:922–7. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–63. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stefanova N. γ-Aminobutyric acid-immunoreactive neurons in the amygdala of the rat—sex differences and effect of early postnatal castration. Neurosci Lett. 1998;255:175–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00735-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoehr JD, Wenk GL. Effects of age and lesions of the nucleus basalis on contextual fear conditioning. Psychobiology. 1995;23:173–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vastola BJ, Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in adolescent and adult rats. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:107–14. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Bohlen und Halbach O, Unsicker K. Morphological alterations in the amygdala and hippocampus of mice during ageing. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:2434–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waddell J, Bangasser DA, Shors TJ. The basolateral nucleus of the amygdala is necessary to induce the opposing effects of stressful experience on learning in males and females. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5290–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1129-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wainwright NWJ, Surtees PG. Childhood adversity, gender and depression over the life-course. J Affect Disord. 2002;72:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White NM, Carr GD. The conditioned place preference is affected by two independent reinforcement processes. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood GE, Beylin AV, Shors TJ. The contribution of adrenal and reproductive hormones to the opposing effects of stress on trace conditioning in males versus females. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:175–87. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]