Abstract

Gene amplification plays important roles in the progression of cancer and contributes to acquired drug resistance during treatment. Amplification can initiate via dicentric palindromic chromosome production and subsequent breakage–fusion–bridge cycles. Here we show that, in fission yeast, acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes form by homologous recombination protein-dependent fusion of nearby inverted repeats, and that these fusions occur frequently when replication forks arrest within the inverted repeats. Genetic and molecular analyses suggest that these acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes arise not by previously described mechanisms, but by a replication template exchange mechanism that does not involve a DNA double-strand break. We thus propose an alternative mechanism for the generation of palindromic chromosomes dependent on replication fork arrest at closely spaced inverted repeats.

Keywords: RTS7, template switch, recombination, gene amplification, breakage–fusion–bridge

Oncogene amplification is often an early event in cancer development, providing a proliferative advantage for clonal expansion (Slamon et al. 1987; Futreal et al. 2004), while the amplification of genes involved in drug metabolism is a common mechanism by which tumor cells acquire chemotherapy resistance (Gorre et al. 2001). Models for the mechanism of gene amplification implicate the initial formation of a dicentric chromosome that subsequently undergoes repeated breakage–fusion–bridge (BFB) cycles. Following multiple BFB events, dicentric chromosomes can ultimately be stabilized by telomere addition at break sites to form monocentric chromosomes containing megabase-sized palindromic regions. These regions are proposed to form a platform for subsequent gene amplification (segmental amplification) by aberrant recombination or replication (McClintock 1941; Lobachev et al. 2002; Debatisse and Malfor 2005; Rattray et al. 2005; Tanaka et al. 2005; Watanabe and Horiuchi 2005). Acentric palindromic chromosomes have been proposed to be precursors for extrachromosomal elements, including “double minutes,” and, at least in yeast models, can accumulate in response to selection for gene amplification (Albrecht et al. 2000; Narayanan et al. 2006).

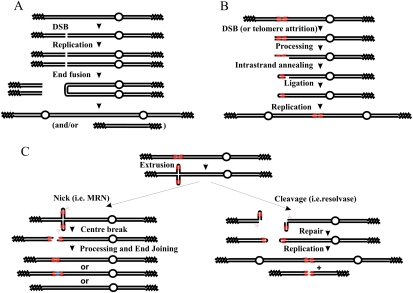

The initial formation of dicentric chromosomes that precede BFB cycles has proved hard to directly visualize, and thus the mechanisms that have been proposed for their formation are based on the analysis of the structures of their stabilized products (Chen and Kolodner 1999; Pennaneach and Kolodner 2004; Haber and Debatisse 2006; Lewis and Cote 2006; Lobachev et al. 2007). Current models for palindromic chromosome formation fall into three categories. In the first (Fig. 1A), palindromic chromosomes are produced following either a double-strand break (DSB) or telomere attrition in G1 phase of the cell cycle. Following DNA replication, two identical broken sisters are produced in G2 phase. Direct ligation of the two intersister uncapped DNA ends—for example, by nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) (Pennaneach and Kolodner 2004)—produces a palindromic dicentric or acentric chromosome. This mechanism should require Ku70 and Lig4, proteins essential for NHEJ. In the second category, a single DSB occurs close to a small inverted repeat (Fig. 1B). Following processing to generate a short region of ssDNA, repeat-mediated intrastrand annealing and subsequent ligation form a chromosomal fragment with one hairpin-capped end. DNA replication will resolve this structure into a giant palindromic chromosome, unless the hairpin is first cleaved by an endonuclease such as those associated with the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) complex. This mechanism should involve specific nucleases and proteins involved in single-strand annealing and be independent of homologous recombination (HR). In the third model, relevant only to palindromic sequences, the hairpin extrudes and is then broken at one of two sites (Fig. 1C): If a nuclease (i.e., MRN) nicks both of the extruded hairpin ends simultaneously (Fig. 1C, left), this causes a DSB that, following processing and end-joining, can result in reformation of the chromosome (often associated with loss or gain of sequences at the palindrome center). Alternatively, the extruded palindrome, which resembles a Holliday Junction (HJ), can be cleaved centrally by structure-specific nucleases. The consequence of this is the formation of a hairpin-capped chromosome end (Fig. 1C, right). As for model B, DNA replication can resolve this into a palindromic chromosome. This mechanism should involve Holliday structure nucleases, depend on the ability of the palindrome to extrude, and be independent of HR.

Figure 1.

Generation of palindromic chromosomes. (A) An uncapped end is generated by a DSB (or by telomere attrition, not shown). The resulting molecule is then replicated, producing two identical uncapped sister chromatids. The two free ends are directly ligated (for example, by NHEJ), and this results in a palindromic dicentric or acentric palindrome. Open circles indicate centromeres, zig-zag lines represents telomeres, and single lines indicate ssDNA. (B) An uncapped end near a short inverted repeat (in red) can, after processing to reveal ssDNA, result in a “snap-back” strand annealing between the inverted repeats, generating a hairpin at the chromosome end. Following fill-in and ligation, this will generate a capped end that resolves into a giant palindrome after DNA replication. (C) If the palindrome extrudes, it will generate a cruciform structure. This resembles an HJ, has hairpin ends, and can be processed by a structure-specific nuclease such as Mus81 (right) or by the MRN complex (left). (Left) If both hairpins are cleaved at the apex by MRN, this results in a break at the center of the palindrome. This can subsequently be repaired by end-joining. This process can result in gain or loss of sequences at the center of the palindrome (blue), and ultimately result in its stabilization or complete loss. If the extrusion is cleaved by HJ resolvase, it is able to form hairpin-capped chromosomes by ligation. Following DNA replication, these can result in acentric and dicentric giant palindromes. This process is suppressed by MRN activity, which can open the hairpin at the chromosome end, thus generating an uncapped end, a substrate for schematic A.

The early stages of carcinogenesis are proposed to be associated with oncogene-mediated replication-dependent genomic instability (Bartkova et al. 2005; Gorgoulis et al. 2005), and proliferating tumor cells exhibit genetic instability associated with deregulated replication (Vogelstein and Kinzler 2004; Aguilera and Gomez-Gonzalez 2008). Thus, we set out to test how replication fork arrest influences the formation of dicentric and acentric palindromic chromosomes. Using a series of inverted repeat and palindromic loci in fission yeast, we find that nearby inverted repeats can fuse to form acentric and dicentric chromosomes, that they do so at high frequency when DNA replication is arrested within the repeats, that the majority of events are HR protein-dependent, and that these chromosomal rearrangements occur independently of a DSB intermediate. Our analysis leads us to propose a new replication template exchange (RTE) model for palindromic chromosome formation.

Results

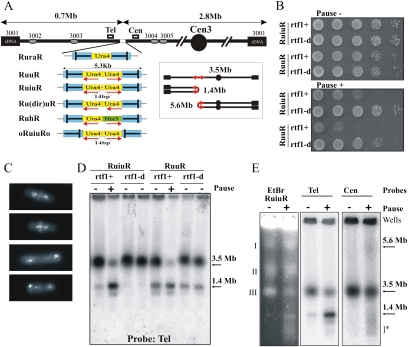

We demonstrated previously that replication fork arrest leads to increased recombination and gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs). The experimental system used (RuraR) (see Fig. 2A) consisted of two 859-base-pair (bp) replication termination sequences (RTS1) introduced at the ura4+ locus as inverted repeats flanking 1.7 kb of nonrepetitive DNA (Lambert et al. 2005). In RuraR, the RTS1 sequences serve two functions: They are inverted repeats that can recombine to fuse with each other, and they provide the means to conditionally and efficiently stall replication forks. To probe the effect of fork arrest within a small perfect or imperfect palindrome, we modified the locus to create a related series of constructs (Fig. 2A). These include (1) a perfect 5.3-kb palindrome that contains the inverted replication arrest sites as its terminal sequences, with two ura4 sequences in inverted orientation (RuuR); (2) a similar construct in which the palindrome center is interrupted by a 14-bp “spacer” (RuiuR); (3) a series of constructs to examine repeat orientation and size [Ru(dir)uR] plus transcriptional orientation and size (RuhR); and (4) a construct to examine the orientation of the replication fork barriers (oRuiuRo).

Figure 2.

Replication fork arrest within a palindrome causes the formation of acentric and dicentric chromosomes. (A) Schematic of the constructs integrated at the ura4 locus on ChrIII. (Blue) RTS1; polar RTS1. The bar in RTS1 indicates the direction that, when a fork approaches, it will be arrested. Red arrows below the ura4 (yellow) and his3 (green) sequences indicate the direction of transcription. Boxes Cen and Tel indicate position of probes used. Ovals show the ars sequences. (Inset) Schematic of acentric and dicentric chromosomes. The 14-bp insertion interrupts the symmetry of the palindrome center in RuiuR and oRuiuRo. (B) Viability analysis of perfect (RuuR) and interrupted (RuiuR) palindrome strains in the presence (pause on; +, rtf1+) and absence (pause off; −, rtf1+ or rtf1-d) of fork arrest. Note that loss of viability is dependent on fork arrest by rtf1+ induction. (C) Representative images of RuiuR mitotic catastrophe 24 h after thiamine removal (approximately three generations of growth under conditions in which forks arrest at RTS1). DNA stained with DAPI, and septum stained with Calcofluor. (D) PFGE and Southern blot analysis of strains either unable to arrest forks at RTS1 (rtf1Δ) or where rtf1 is regulated by thiamine ([−] low transcript and minimal arrest; [+] high transcript and efficient fork arrest). Note that formation of 1.4-Mb DNA is correlated with loss of viability in B. (E) PFGE and Southern blot analysis of cells without fork arrest (off; −) and 24 h after (on; +) arrest is induced. (Left panel) Ethidium bromide staining. (Middle panel) Telomere-proximal probe. (Right panel) Centromere-proximal probe. I, II and III indicate fission yeast chromosomes. Arrows: 3.5 Mb, ChrIII; 1.4 Mb, acentric; 5.6 Mb, dicentric. (*) Smear corresponding to breakage.

Fork arrest at RTS1 has been extensively characterized; it is direction-dependent and requires the Rtf1 protein (Codlin and Dalgaard 2003; Eydmann et al. 2008). In the absence of the rtf1+ gene, we and others have demonstrated that replication forks no longer arrest at RTS1 and that this sequence is replicated normally (Lambert et al. 2005). To regulate fork arrest, we thus used an attenuated thiamine-repressible promoter (nmt41) to regulate rtf1+ transcription at its own locus (nmt:rtf1+). Because repression is somewhat leaky, we also used an rtf1-null (rtf1-d) mutant background to entirely eliminate programmed fork arrest at RTS1. In the presence of induced Rtf1 protein, >95% of the forks arrest at the RTS1 (Supplemental Fig. S1; data not shown), and HR protein-dependent mechanisms are required to process them to restart replication (Lambert et al. 2005).

Fork arrest within a palindrome causes a high frequency of chromosomal rearrangement

RuuR cells (harboring the perfect small palindrome) and RuiuR cells (interrupted small palindrome), respectively, exhibit either modest or no viability loss in the absence of Rtf1 (compared with a control strain not harboring the construct) (Fig. 2B; data not shown). When rtf1+ is induced (nmt:rtf1 without thiamine) to switch on fork arrest, both RuuR and RuiuR cells showed significant viability loss (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S2). This inviability correlated with the appearance of a mitotic catastrophe phenotype in ∼20%–25% of cells (Fig. 2C), and the production of a 1.4-Mb acentric giant palindromic chromosome (pulse field gel [PFG] analysis) (Fig. 2D). Restriction fragment analysis by Southern blot demonstrated that DNA fragments consistent with both acentric and dicentric chromosomes are rapidly produced at approximately equal frequency (Supplemental Fig. S3). When transcription is repressed (nmt:rtf1+ with thiamine), low levels of rearrangement are observed in both RuuR and RuiuR cells (Fig. 2D). However, when the rft1+ gene is deleted (rtf1-d), this low level of rearrangement is not seen for the interrupted palindrome construct (RuiuR), but remains detectable for the perfect palindrome (RuuR) (Fig. 2D). Thus, the GCRs visible in RuiuR cells are rtf1+-dependent and are induced by replication fork arrest. The RuuR construct is somewhat unstable even in the absence of rtf1+ and replication fork arrest. We infer that the perfect palindrome forms rearrangements due to spontaneous cruciform extrusion, and that this is prevented by stabilizing the palindrome center with a 14-bp insertion. We thus concentrated further analysis on the interrupted palindrome (RuiuR) system, where rearrangement is dependent on replication fork arrest.

We next evaluated the percentage of chromosomal rearrangements. We can visualize four molecular species that help answer this question: First, probing a PFG with a centromere-proximal probe visualizes a faint 5.6-Mb band (Fig. 2E), corresponding to the size of the dicentric chromosome (Fig. 2A, inset) and predicted from restriction enzyme analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3). Second, a smear of smaller fragments suggests random breakage of the dicentric chromosome during mitosis. This is consistent with the visualization of DAPI-staining material stretched between two nuclei following mitosis (Fig. 2C). Third, we can visualize the acentric chromosome formed, and fourth, we can visualize the original chromosome III (ChrIII).

When arrest is induced, there is an increase in all three species indicative of the acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosome formation (1.4- and 5.6-Mb chromosomes and a smear of small fragments). The majority of the 3.5-Mb ChrIII band is also absent from PFGs (see Figs. 2, 3; Supplemental Fig. S4). It is likely that ChrIII does not enter the gel efficiently when replication is stalled and restarted by HR protein-dependent mechanisms, because joint molecules that are produced as intermediates during restart by HR proteins accumulate (Supplemental Fig. S1). Unfortunately, under the PFG electrophoresis (PFGE) conditions used to resolve fission yeast chromosomes, it is not possible to quantify the DNA remaining in the wells. We interpret the dramatic loss of ChrIII as a combination of two events: First, a percentage of the chromosomes undergo GCRs to form acentric and dicentric products. Second, the remaining chromosomes, while ultimately completing replication following fork restart, are, for a significant time, in possession of replication and joint molecule intermediates that preclude PFG entry. This is consistent with our demonstration that RTS1 sites integrated at this locus arrest the majority of replication forks (Supplemental Fig. S1; Lambert et al. 2005), which are subsequently restarted by HR protein-dependent mechanisms.

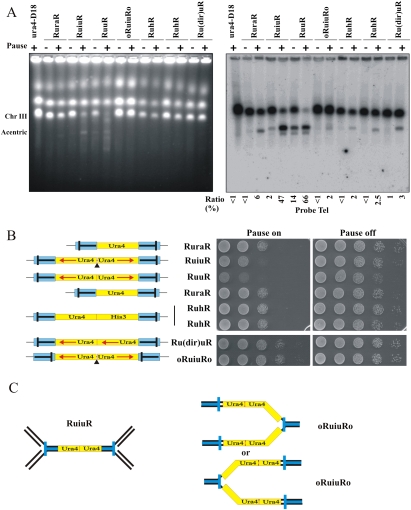

Figure 3.

Fork arrest at inverted repeats also results in large palindromic chromosomes. (A) PFGE of DNA from the indicated strains either without (off; −) or 48 h after (on; +) the induction of rtf1-dependent fork arrest. (Left) Ethidium stained. (Right) Southern blotted with a telomere-proximal probe. The percentage of signal corresponding to the acentric chromosome (1.4 Mb) was calculated (numerals) as a percentage of total signal (2 × 3.5 Mb + 1.4 Mb). (B, left) Schematic. (Blue) RTS1. (Bar in RTS1) The direction that, when a fork approaches, it will be arrested. Red arrows below ura4 (yellow) and his3 (green) indicate direction of transcription. (Solid triangle) 14-bp “interruption”. (Right) Viability analysis in the absence (Pause on) or presence (Pause off) of thiamine to regulate rtf1 for the strains indicated. (C) Schematic of the expected pattern of replication arrest for RuiuR and oRuiuRo. The blue bar indicates the direction that, when a fork approaches, it will be arrested.

Acentric palindromic chromosomes are also generated from nearby inverted repeats

Near-perfect palindromes are uncommon in the human genome (Bailey et al. 2002). More common are repeated sequences such as Alu elements that are usually separated by other sequences. Interestingly, very closely spaced inverted Alu repeats and Alu palindromes are significantly underrepresented (Lobachev et al. 2000; Stenger et al. 2001), suggesting specific evolutionary pressure against such arrangements. To establish if our model system has relevance to spontaneous genomic rearrangements at endogenous inverted repeat structures, we examined if acentric chromosomal palindromes could occur as a consequence of replication fork stalling within nearby inverted repeats.

First, we studied rearrangements in the original RuraR construct (859-bp repeats separated by 1.7 kb), as well as additional constructs that contain nonpalindromic sequences between the RTS1 inverted repeats (see Fig. 2A). We found that all constructs containing RTS1 inverted repeats flanking unique sequences generated acentric (Fig. 3A) and dicentric chromosomes (data not shown) when replication forks are arrested in the repeats. Thus, these constructs undergo inverted repeat fusion, but at a >10-fold lower frequency than seen for RuiuR. Consistent with this, they do not significantly lose viability upon induction of fork arrest (Fig. 3B, right). We also included a construct (oRuiuRo) in which the orientation of the RTS1 polar replication fork barrier was inverted compared with RuiuR. The significance of this construct is that forks must pass through the palindrome before being arrested (Fig. 3C), making arrest possible at only one site in any one S phase. The oRuiuRo construct forms detectable levels of the acentric chromosome upon fork arrest. Thus, a single arrested fork within an interrupted small palindrome (oRuiuRo) can precipitate the production of palindromic chromosomes.

Genetic test for the mechanism of acentric palindrome chromosome formation

We next tested various models for palindromic chromosome formation. To review, each of the three mechanisms presented in Figure 1 makes concrete genetic predictions (Butler et al. 2002; Cote and Lewis 2008). For model A, where chromosomes break, replicate, and then fuse, NHEJ would be required. For model B (intramolecular annealing), structure-specific nucleases Rad32Mre11 (MRN) and Rad16Rad1–Swi10Rad10 are implicated, and there is no expected dependence on the strand invasion HR protein Rhp51Rad51. Model C (cruciform cleavage) implicates HJ nucleases Slx1/4 and Mus81 and also predicts independence from strand invasion protein Rhp51Rad51. Lastly, a chromosome break within the repeat followed by break-induced replication (BIR) would implicate the full range of HR proteins (Llorente et al. 2008).

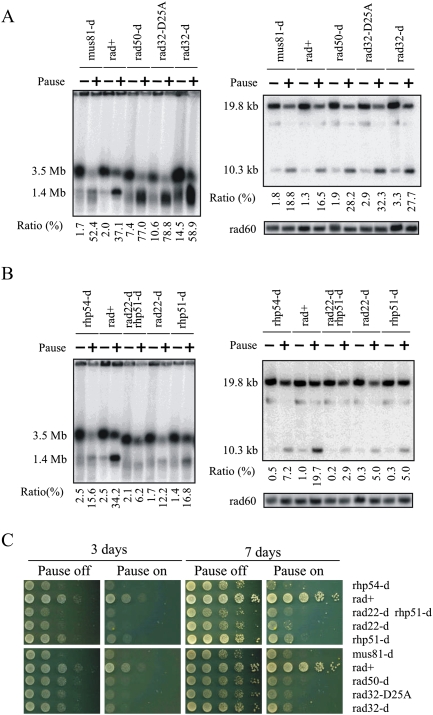

We thus analyzed cell viability and the production of the acentric chromosome in a variety of genetic backgrounds. Loss of the Pku70, Lig4, Slx1, Rad32Mre11, or Swi10Rad1/Rad16Rad10 nucleases did not reduce acentric formation (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. S5A,C,E,F). Loss of Mus81 slightly increased rearrangement (Fig. 4A). From this we conclude that the main mechanism producing the acentric and dicentric chromosomes is not chromosome fusion (NHEJ-dependent), intramolecular strand annealing, or cleavage of cruciform extrusion (MRN, Swi10Rad1/Rad16Rad10, or Slx1/4, Mus81-dependent).

Figure 4.

HR proteins are required for viability and GCR. (A,B) DNA prepared from RuiuR strains indicated, grown either without (off; −) or three generations after (on; +) the induction of rtf1-dependent fork arrest, was analyzed by either PFGE (left) or SalI digestion (right) (see Supplemental Fig. S3C for SalI fragments) and Southern blotting with a telomere-proximal probe. The panel labeled “rad60” represents the same gel probed with a ChrII-specific probe. (Bottom) The ratio of signal corresponding to the acentric chromosome (1.4 Mb or 10.3 kb, respectively, expressed as a percentage) was calculated compared with total signal (2 × 3.5 Mb + 1.4 Mb or 2 × 19.8 kb + 10.3 kb). The rad22Δ rhp51Δ strain was used because rad22rad52 mutants can accumulate suppressors that are Rhp51Rad51-dependent. rad32 = mre11. (C) Viability analysis in the presence (Pause off) or absence (Pause on) of thiamine to regulate rtf1.

We next analyzed the role of HR proteins (Fig. 4B). Upon expression of rft1+ (no thiamine), loss of core HR proteins Rhp51Rad51, Rhp54Rad54, or Rad22Rad52 decreased acentric formation ∼90% when compared with rad+ cells. This supports the elimination of models for intramolecular strand annealing and cleavage of cruciform extrusion (which should be independent of strand invasion). Cell death in HR mutant backgrounds, when compared with rad+ cells, was greatly increased (Fig. 4C). Our previous data supported the notion that, following replication fork arrest at RTS1, HR proteins are required for replication restart. Thus, we propose three fates for a stalled fork: The first is replication resumption via an HR protein-dependent mechanism that leads to an unaltered ChrIII. Cells undergoing this event are viable (Lambert et al. 2005). A second fate is to restart replication at the expense of recombination protein-dependent fusion between repeats to form acentric and dicentric chromosomes. These cells are inviable. The third fate is failure to resume replication. Such cells do not undergo subsequent repeat fusion, but are inviable due to incomplete replication. rad+ cells usually resume or resume and fuse their repeats (fates one and two), while HR mutants generally fail to resume and thus also fail to form repeat fusions.

In the MRN mutant backgrounds, we observe an increase in the level of rearrangements upon quantification of both PFGE and restriction fragment analysis (Fig. 4A). This is combined with viability loss (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S2). This indicates that recombination protein-dependent processing of the stalled fork does occur in these cells, but that it may be inappropriately channeled into lethal events, some of which result in giant palindromic chromosome formation. Alternatively, the accumulation of palindromic chromosomes in MRN mutants could reflect a combination of two effects: a loss of the predominant HR protein-dependent mechanism of fork restart (and thus of palindrome formation), combined with the loss of a usually cryptic role for Rad32Mre11 nuclease activity in suppressing alternative pathways (i.e., Fig. 1C, right) that lead to an equivalent rearrangement via mechanisms that rely on the generation of hairpin ends (Lobachev et al. 2002). Mre11 is proposed to efficiently cleave such structures.

Evidence for a lack of DSBs associated with the rearrangement

Current models for replication fork restart, derived largely from Escherichia coli, invoke a one-ended DSB that recruits HR to invade the partially replicated sister chromosome to reinitiate replication (Haber and Heyer 2001). Such a BIR model would explain both the requirement for HR proteins for cell viability (correct fork restart) and our genetic data for palindromic chromosome formation (incorrect invasion of the twin repeat resulting in BIR replicating to the chromosome end). To test for DSBs associated with replication fork restart, we took two approaches: First, we used both the RuiuR and the RuraR constructs to look for evidence of DSBs by PFGE and restriction fragment analysis. Second, we used synchronized RuraR cells to look for DSBs within a single cell cycle. We reasoned that, if replication fork restart initiates via BIR, the majority of chromosomes in our cultures must be transiently broken and exhibit a polar DSB (the majority of forks arrest at the RTS1 sequences) (Supplemental Fig. S1; Lambert et al. 2005), and recombination proteins will be required for their restart (Fig. 4; Lambert et al. 2005). A chromosomal fragment with a polar DSB will first be processed by MRN-dependent nuclease, bound by Rad51 filament, and subsequently initiate invasion of the partially replicated sister chromosome. Thus, to eliminate the possibility that we could fail to detect DSBs due to rapid processing and/or the initiation of recombination, we also analyzed strains in which MRN was defective (delayed processing) and/or strand invasion was prevented (Rad22Rad52 or Rhp51Rad51 absent).

In our first approach, we examined both RuiuR and RuraR in repair-competent (rad+) and HR processing and repair-deficient backgrounds by PFGE and restriction fragment analysis (Fig. 5). A polar DSB caused by replication arrest in either RuiuR or RuraR would be detected as a centromere-proximal fragment of 2.8 Mb on PFGs probed with sequences corresponding to the right arm of ChrIII. If first cleaved by the rare cutter AscI, this would reduce the fragment size to ∼650 kb when combined with a polar break at RuiuR (Fig. 5A). However, analysis of native and AscI cleaved samples did not reveal a band diagnostic of a DSB at RuiuR (Fig. 5B). Similarly, we could find no evidence for a significant fraction of DSBs associated with forks arrested at RTS1 in RuraR backgrounds (Fig. 5D). Consistent with these PFG analyses, we did not detect DSBs upon fork arrest by restriction fragment analysis in either the RuraR (Fig. 5C) or RuiuR (data not shown) backgrounds.

Figure 5.

Fork arrest at RuiuR or RuraR results in chromosomal rearrangement without DSB formation in rad+ cells and in processing (rad50) and recombination (rad22rad52) of defective mutants. (A) Schematic of the RuiuR or RuraR constructs integrated at the ura4 locus of ChrIII. The bar in RTS1 indicates the direction that, when a fork approaches, it will be arrested. Boxes ade6 and rng3, the bar cen, and the circle cent3 indicate the positions of probes. Note that ARS3004 and ARS3005 are efficient ARSs. The single AscI site is indicated. (B, left) Southern hybridization of a PFG using a centromere-proximal probe either without the induction of rtf1-dependent replication fork arrest (pause −) or 48 h after the induction (pause +) in the indicated RuiuR strains. If a DSB occurred at RuiuR, a 2.8-Mb band would represent a fragment derived from the DSB to the right telomere. This was not seen; the expected position is indicated by a red bar. (Right) AscI-digested DNA was analyzed by PFGE and Southern blotting with a centromere-proximal probe. The AscI site is a unique site on S. pombe ChrIII and would generate a 650-kb fragment if combined with a DSB at RuiuR. No such signal is seen; compare tracks 3 and 4. The expected position is indicated by a red bar. (C) Southern blot analysis of AvaI restriction fragment derived from indicated RuraR strains without (−) and 24 h after (+) arrest is induced. Asterisk (*) represents a nonspecific band. Below is a schematic of the RuraR construct digested by the restriction enzyme AvaI. A polar DSB would result in the generation of a 2.2-kb fragment revealed with the Cen probe. This was not seen; the expected position is indicated by a red bar. (D, left) A PFG of chromosomes from the indicated RuraR strains stained with ethidium bromide or probed with indicated probes. (−) Pause off; (+) pause on for 24 h. Positions of H. wingei chromosomes are indicated as size markers. The bold arrow indicates the position of the acentric chromosome at 1.4 Mb. The predicted fragment in the case of a DSB at RuraR is 0.7 Mb for the Rng3 probe. The ade6 and cent3 probes would show a 2.8-Mb fragment in the case of a DSB. These were not detected; the expected positions are indicated on the right by a red bar. In the absence of both Rad50 and Rad22Rad52 (DSB resection and HR), a smear above 2.8 Mb is evident. However, this appeared whatever ChrIII probe was used, which thus does not reflect a specific polar DSB, but likely reflects fragmentation of the chromosome.

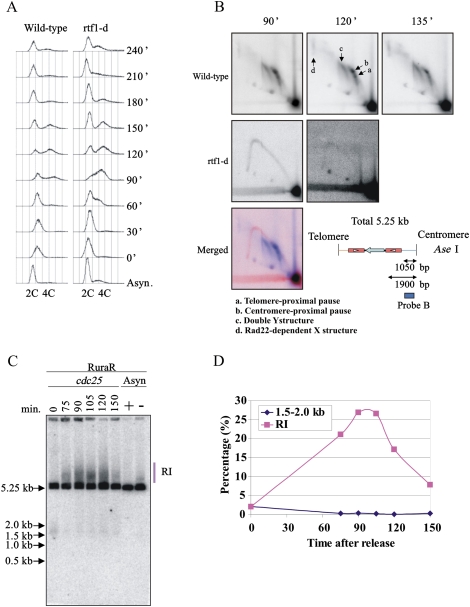

In the second approach, we sought to detect DSBs when a culture harboring RuraR was synchronized in G2 and released into a synchronous S phase following induction of nmt:rtf1 to switch on fork arrest (Fig. 6). We induced rtf1+, synchronized cells in G2 phase with a cdc25-22 temperature-sensitive mutant at 36°C, and released cells into the next cell cycle by temperature shiftdown. FACS analysis showed that bulk replication occurs at ∼90 min and is complete by ∼150 min after release from the cdc25 block (Fig. 6A). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis demonstrated the efficiency of replication arrest and its dependence on Rtf1 (Fig. 6B). As in our previous work (Lambert et al. 2005), in the presence of fork arrest we could not detect Y molecules that would correspond to normal replication fork progression through the locus because most forks are arrested at the RTS1. Southern analysis of AseI-digested DNA (Fig. 6C) showed that >25% of the DNA is present in a high-molecular-weight smear that peaked during S phase (Fig. 6D). This likely represents the replication and/or recombination protein-dependent intermediates visualized in Figure 6B. We could not detect evidence for an S-phase-specific DSB at the RTS1 site. Taken together, these experiments provide strong evidence that replication restart by recombination protein-dependent mechanisms in this system is not associated with DSBs at the site of fork arrest, and is thus independent of BIR.

Figure 6.

Absence of a detectable DSB induction in synchronized cells. RuraR rtf1+ and RuraR rtf1-d cells were grown without thiamine (14 h) and were synchronized by cdc25.22 block and release. The time course starts after cell cycle release. Asynchronous cultures were grown for 24 h with (−; pause off) and without (+; pause on) thiamine as a control where appropriate. (A) FACS analysis. The culture before the cell cycle arrest was used as asynchronous control culture “Async.” S phase occurs between 60 and 150 min. (B) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis at specified time points with (rtf1+) and without (rtf1-d) fork arrest (a–d as indicated) (see Supplemental Fig. S1). (Bottom) Map of AseI digest for RuraR. The position of the Cen probe is indicated by the bar. In the merged picture, the signal corresponding to 90 min for rtf1-d is red and that for rtf1+ is blue. (C) Southern hybridization of one-dimensional gel to visualize replication intermediates (RI) from the indicated times. DNA was digested with AseI. (D) Quantification of one-dimensional gel showing the percentage total signal present in replication intermediates (red squares) and at the position of a predicted break (blue diamonds). Forks broken within the Cen-proximal RTS1 would generate a band of ∼1500 bp. A faint signal between 1.5 and 2.0 kb is seen in the G2-arrested sample (0 min), but this is lost when cells enter S phase (75 min).

Discussion

Palindromes are thought to be underrepresented in the genome because they are intrinsically unstable and can be eliminated by a variety of processes in both meiosis (Nasar et al. 2000; Farah et al. 2005) and mitosis (Lewis and Cote 2006; Lobachev et al. 2007). Closely spaced inverted repeats with <20 bp of separation are also underrepresented, likely due to evolutionary counterselection. Even when repeat homology is as low as 86%, such closely spaced inverted repeats can underlie the generation of palindromic chromosomes (Lobachev et al. 2000). Here we report a model system that helps to explain why these two classes of repeat geometries are underrepresented: They can form acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes when replication forks stall within them. We show that recombination proteins are required for the majority of these GCRs, and that the inverted repeats can fuse by a mechanism that does not appear to involve a DNA DSB and is thus independent of BIR.

Replication restart and chromosome rearrangements can occur independently of DSBs

Fork arrest occurs at ∼95% of RTS1 sequences when fork stalling is induced in our systems in either rad+ or HR mutant backgrounds (see Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S1; data not shown). Resumption of replication requires HR proteins, and this is reflected in a dramatic loss of viability for RuiuR cells in an HR mutant background when fork arrest is induced (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S2). In rad+ HR-proficient cells, fork restart at RuiuR occurs at the expense of a high level of chromosome rearrangement into acentric and dicentric chromosomes, which itself causes significant viability loss due to an inability to segregate chromosomes. Analysis of the accumulation of these acentric and dicentric chromosomes demonstrates that an HR protein-dependent mechanism underlies their production. Despite the highly efficient fork arrest and the fact that recombination proteins are required for fork restart, we were unable to detect DSBs associated with fork arrest in synchronized cell populations or in genetic backgrounds deficient in either DNA processing (MRN complex mutants) or strand invasion (HR mutants). Even in the rad50-d rad22-drad52 double mutant background (absence of both processing and strand invasion) (Fig. 5), no DSBs were observed. These data provide a compelling indication that the major mechanism(s) of fork restart and subsequent chromosomal rearrangement in this model system do not proceed via a DSB intermediate and are thus distinct from BIR.

RTS1 is a protein-dependent programmed fork barrier. GCRs, however, are generally associated with stochastic fork stalling. In the absence of programmed fork stalling (rtf1 deletion), we find that the RuiuR locus can generate rearrangements equivalent to Rtf1-dependent GCRs in response to MMS treatment (Supplemental Fig. S6). Thus, while we do not propose that the RTS1/Rtf1 fork arrest-dependent palindromic chromosome formation we visualize here exclusively represents how such deleterious structures arise in response to replication problems, we propose that it provides a relevant model for the generation of rearrangements that are not initiated by DSBs when forks are stochastically stalled within short palindromes.

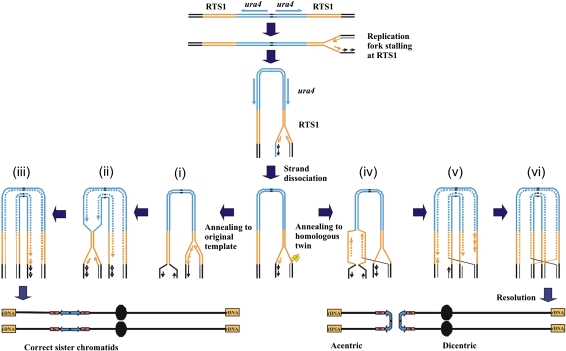

An RTE model for fork restart-associated chromosome rearrangements

In E. coli, fork restart by HR commonly proceeds through a polar DSB intermediate (Haber and Heyer 2001). In eukaryotes, it has not been established if DSBs are either a common or essential intermediate during restart (Fabre et al. 2002; Aguilera and Gomez-Gonzalez 2008), but this has often been assumed to be the case. Our analysis demonstrates that fork restart and the subsequent recombination protein-dependent fusion of two inverted repeats that results in palindromic chromosome formation occur independently of a DSB when forks are arrested at RTS1. We also demonstrate that neither the post-replication repair pathway (Supplemental Fig. S5E–G) nor structure-specific nucleases such as Mus81, Mre11, Slx1/4, Rad16Rad1/Swi10Rad10, or Rad2Fen1 (Supplemental Fig. S5C,E–G) are required for fork restart (as judged by viability) or for the subsequent generation of palindromic chromosomes. Thus, we propose that HR protein-dependent replication is initiated from a single-stranded gap at a stalled fork, and that this can result in a template exchange event that results in inappropriate fusion of inverted repeats by a recombination protein-dependent mechanism (Fig. 7). The precise method of such a DSB-independent fork restart process and how it results in the deleterious template exchange remain subjects for future investigation.

Figure 7.

An RTE model for giant palindrome formation. After fork arrest, a recombinogenic 3′ end is formed by association with HR proteins (yellow). (Left) Recombination protein-dependent fork restart results in reinvasion at the correct locus (i) and completion of replication (ii,iii). (Right, iv) Alternatively, erroneous invasion occurs in the opposite repeat. The dashed line indicates an area synthesised by restart of coupled leading and lagging strand synthesis. Replication subsequently continues around the palindrome (v) and creates an HJ following ligation to the lagging strand of the oncoming fork (vi). HJ resolution in the horizontal plane results in acentric and dicentric chromosome formation. Resolution in the vertical plane results in fully replicated chromosomes in the original conformation (not shown).

There is evidence from several systems (i.e., Zhang and Freudenreich 2007; for review, see Aguilera and Gomez-Gonzalez 2008) that DSBs can be associated with fork arrest-induced GCR in eukaryotes, and we do not argue that DSBs cannot be a consequence of fork arrest or an intermediate in fork restart. Distinct replication fork barriers are likely to result in the production of different DNA and/or DNA–protein structures, and these will, in turn, elicit distinct modes of DNA processing and subsequent repair (Lambert and Carr 2005; Lambert et al. 2007; Aguilera and Gomez-Gonzalez 2008). However, in support of the potential relevance of fork restart independent of a DSB at RTS1, it is of interest to note DSB-independent HR has been proposed previously to occur in budding yeast (Payen et al. 2008) and following blocks to mammalian DNA replication by thymidine, in contrast to hydroxyurea treatment, where HR was seen to be associated with DSBs (Lundin et al. 2002). Furthermore, a fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS) mechanism that is potentially independent of DSBs and occurs at sites of microhomology has been proposed to explain noncontiguous DNA sequences associated with non-recurrent complex chromosome rearrangements typical of a number of inherited genomic disorders (Lee et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2009). Taken together, the available literature and our own analysis strengthen the suggestion that the nature of the replication fork barrier influences the mechanisms by which replication is restarted.

Summary

Giant palindromes are precursors to BFB cycles and gene amplifications that underlie both cancer etiology and the amplification of target genes during acquired resistance to chemotherapy. Our DSB-independent HR protein-dependent RTE model for their generation following replication fork arrest within inverted repeats or small palindromic sequences therefore has significant potential consequences for the understanding of the mechanisms of genomic instability associated with palindromic chromosomes, and may also help explain how chromosome regions with complex architectures and fragile sites capable of forming extensive secondary structures (Durkin and Glover 2007; Zhang and Freudenreich 2007) become susceptible to increased plasticity during replication and in response to replication perturbation.

Materials and methods

Strains were constructed using standard genetic techniques (Moreno et al. 1991; Bahler et al. 1998). The Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1. For fluorescence microscopy, cells were stained with DAPI (0.5 μg/mL) and Calcofluor (5 μg/mL) after methanol fixation. The modified nmt1 promoter (nmt41) (Basi et al. 1993) was integrated upstream of the rtf1 ORF (Lambert et al. 2005). Induction following thiamine removal takes 14–16 h. At 24 h, cultures are in a “steady state” after three to four generations of division in the presence of fork arrest. Where appropriate, 100 U of AscI were used to digest DNA in an agarose plug equilibrated with the enzyme buffer recommended by the manufacturer. PFGE was performed as described previously (Lambert et al. 2005). Conditions for Hansenula wingei chromosomes were as recommended by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad). Southern blot hybridization was performed using standard procedures. The signals were visualized with a PhosphorImager, and band intensities were quantified with an ImageQuant TL program. The ratio of the acentric palindromic chromosome to total ChrIII signal is indicated as a percentage and was calculated as 100 × 1.4 Mb/(2 × 3.5 Mb + 1.4 Mb) or 100 × 10.3 kb/(2 × 19.8 kb + 10.3 kb). Note the duplication of the probe sequence in the acentric.

Serial dilution assay of cell growth

Cells were grown at 30°C in yeast extract media with supplements and washed with sterile water twice. Cells (1.6 × 106) were inoculated in 10 mL of EMM2 containing supplements with (pause off) or without (pause on) 30 μM thiamine and grown for 24 h at 30°C. Ten microliters of serial (1:10) dilutions (103–107 cells per milliliter) of the cultures were spotted on yeast nitrogen base agar (YNBA) plates containing supplements either with (pause off) or without (pause on) thiamine. Plates were incubated for 3 d at 30°C. For cell cycle synchronization, strain YKM104 harboring the cdc25.22 allele was used. Cells were grown in EMM2 medium without thiamine for 16 h at 25°C, incubated for 3.5 h at 36°C to block the cell cycle, and then cooled down to 25°C to release them synchronously into the cell cycle.

Probes

Southern blot hybridization was performed using standard procedures with the following probes: Tel probe: a 296-bp PCR-amplified fragment with DU4-for (5′-GGATTCTAACTATGTCTTTTAGAC-3′) and DU4-rev (5′-CTTAAGAAAAAAACGTCAAAAGAAATC-3′); Cen probe: a 410-bp PCR-amplified fragment with L1-1-for (5′-TTTAAATCAAATCTTCCATGCG3′) and L1-1-rev (5′-GATGCCAGACCGTAATGACAAAA-3′); Rad60 probe: a 743-bp PCR-amplified fragment with Rad60cd0 (5′- GACAACCTAGATGAAGA-3′) and Rad60cd60r (5′-TTAGCTGTTTGGAATTCTCTGT-3′); Ura4 and Rng3 probes: as described previously (Lambert et al. 2005).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MRC grant G0600233 (to A.M.C.), CRUK grant C9601/A4849 (to J.M.M.), l'Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant ANR-06-BLAN-0271 (to S.L.), and la Ligue contre le cancer (comité Essonne) (to S.L.).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1863009.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Aguilera A, Gomez-Gonzalez B. Genome instability: A mechanistic view of its causes and consequences. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:204–217. doi: 10.1038/nrg2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht EB, Hunyady AB, Stark GR, Patterson TE. Mechanisms of sod2 gene amplification in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:873–886. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Eichler EE. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basi G, Schmid E, Maundrell K. TATA box mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe nmt1 promoter affect transcription efficiency but not the transcription start point or thiamine repressibility. Gene. 1993;123:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90552-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler DK, Gillespie D, Steele B. Formation of large palindromic DNA by homologous recombination of short inverted repeat sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;161:1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Kolodner RD. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat Genet. 1999;23:81–85. doi: 10.1038/12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codlin S, Dalgaard JZ. Complex mechanism of site-specific DNA replication termination in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2003;22:3431–3440. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote AG, Lewis SM. Mus81-dependent double-strand DNA breaks at in vivo-generated cruciform structures in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2008;31:800–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debatisse M, Malfor B. Gene amplification mechanisms. In: Nigg EA, editor. Genome instability in cancer development. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin SG, Glover TW. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.165900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eydmann T, Sommariva E, Inagawa T, Mian S, Klar AJ, Dalgaard JZ. Rtf1-mediated eukaryotic site-specific replication termination. Genetics. 2008;180:27–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre F, Chan A, Heyer WD, Gangloff S. Alternate pathways involving Sgs1/Top3, Mus81/Mms4, and Srs2 prevent formation of toxic recombination intermediates from single-stranded gaps created by DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:16887–16892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252652399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah JA, Cromie G, Steiner WW, Smith GR. A novel recombination pathway initiated by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex eliminates palindromes during meiosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2005;169:1261–1274. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, Venere M, Ditullio RA, Jr, Kastrinakis NG, Levy B, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, Hsu N, Paquette R, Rao PN, Sawyers CL. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293:876–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE, Debatisse M. Gene amplification: Yeast takes a turn. Cell. 2006;125:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE, Heyer WD. The fuss about Mus81. Cell. 2001;107:551–554. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00593-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S, Carr AM. Checkpoint responses to replication fork barriers. Biochimie. 2005;87:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S, Watson A, Sheedy DM, Martin B, Carr AM. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell. 2005;121:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S, Froget B, Carr AM. Arrested replication fork processing: Interplay between checkpoints and recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1042–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SM, Cote AG. Palindromes and genomic stress fractures: Bracing and repairing the damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1146–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente B, Smith CE, Symington LS. Break-induced replication: What is it and what is it for? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:859–864. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobachev KS, Stenger JE, Kozyreva OG, Jurka J, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Inverted Alu repeats unstable in yeast are excluded from the human genome. EMBO J. 2000;19:3822–3830. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobachev KS, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The Mre11 complex is required for repair of hairpin-capped double-strand breaks and prevention of chromosome rearrangements. Cell. 2002;108:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobachev KS, Rattray A, Narayanan V. Hairpin- and cruciform-mediated chromosome breakage: Causes and consequences in eukaryotic cells. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4208–4220. doi: 10.2741/2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin C, Erixon K, Arnaudeau C, Schultz N, Jenssen D, Meuth M, Helleday T. Different roles for nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination following replication arrest in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5869–5878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5869-5878.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The stability of broken ends of chromosomes in Zea mays. Genetics. 1941;26:234–282. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan V, Mieczkowski PA, Kim HM, Petes TD, Lobachev KS. The pattern of gene amplification is determined by the chromosomal location of hairpin-capped breaks. Cell. 2006;125:1283–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasar F, Jankowski C, Nag DK. Long palindromic sequences induce double-strand breaks during meiosis in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3449–3458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3449-3458.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payen C, Koszul R, Dujon B, Fischer G. Segmental duplications arise from Pol32-dependent repair of broken forks through two alternative replication-based mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennaneach V, Kolodner RD. Recombination and the Tel1 and Mec1 checkpoints differentially effect genome rearrangements driven by telomere dysfunction in yeast. Nat Genet. 2004;36:612–617. doi: 10.1038/ng1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattray AJ, Shafer BK, Neelam B, Strathern JN. A mechanism of palindromic gene amplification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:1390–1399. doi: 10.1101/gad.1315805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger JE, Lobachev KS, Gordenin D, Darden TA, Jurka J, Resnick MA. Biased distribution of inverted and direct Alus in the human genome: Implications for insertion, exclusion, and genome stability. Genome Res. 2001;11:12–27. doi: 10.1101/gr.158801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Bergstrom DA, Yao MC, Tapscott SJ. Widespread and nonrandom distribution of DNA palindromes in cancer cells provides a structural platform for subsequent gene amplification. Nat Genet. 2005;37:320–327. doi: 10.1038/ng1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Horiuchi T. A novel gene amplification system in yeast based on double rolling-circle replication. EMBO J. 2005;24:190–198. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Freudenreich CH. An AT-rich sequence in human common fragile site FRA16D causes fork stalling and chromosome breakage in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2007;27:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Khajavi M, Connolly AM, Towne CF, Batish SD, Lupski JR. The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nat Genet. 2009;41:849–853. doi: 10.1038/ng.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]