Abstract

Renal injury distal to an atherosclerotic renovascular obstruction reflects multiple intrinsic factors producing parenchymal tissue injury. Atherosclerotic disease pathways superimposed on renal arterial obstruction may aggravate damage to the kidney and other target organs, and some of the factors activated by renal artery stenosis may in turn accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis. This cross talk is mediated through amplified activation of renin-angiotensin system, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, pathways notoriously involved in renal disease progression. Oxidation of lipids also accelerates the development of fibrosis in the stenotic kidney by amplifying profibrotic mechanisms and disrupting tissue remodeling. The extent to which actual ischemia modulates injury in the stenotic kidney has been controversial, partly because the decrease in renal oxygen consumption usually parallels a decrease in renal blood flow, and because renal vein oxygen pressure in the affected kidney is not decreased. However, recent data using novel methodologies demonstrate that intra-renal oxygenation is heterogeneously affected in different regions of the kidney. Activation of such local injury within the kidney may lead to renal dysfunction and structural injury, and ultimately unfavorable and irreversible renal outcomes. Identification of specific pathways producing progressive renal injury may enable development of targeted interventions to block these pathways and preserve the stenotic kidney.

Keywords: renal artery stenosis, atherosclerosis, ischemia

BACKGROUND

Renovascular nephropathy is becoming more frequently identified in patients with chronic and end-stage renal disease as the population ages. Significant renal artery stenosis (RAS) (≥60% lumen occlusion), usually caused by atheromatous plaques, is present in almost 7% of adults older than 65 (1) and up to 50% of patients presenting with diffuse atherosclerotic disease (2). In addition to threatening renal function, atherosclerotic renovascular disease with renal failure poses a risk for exacerbation of cardiovascular disease (3, 4) and predicts cardiovascular mortality (5, 6). Hence, the mechanisms responsible for renal and cardiovascular damage in this disease are being vigorously sought, and effective therapeutic strategies to preserve the kidney are under intense investigation.

Several recent lines of evidence highlight the pathophysiological complexity of atherosclerotic renovascular disease. The elusive nature of this disease is underscored by the poorer outcomes compared to fibromuscular dysplasia (7), which comprises the second most common etiology for RAS and involves a localized renal arterial lesion. Restoration of vascular patency for fibromuscular dysplasia regularly produces “cure” and improvement for renovascular hypertension (8). By contrast, results from recent clinical trials for patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease indicate that revascularization with percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA) and stenting improve blood pressure (9) or recover renal function (10, 11) inconsistently. Surgical correction of atherosclerotic renovascular disease also results in blood pressure benefit and retrieval of renal function only in selected patients (12), arguing against technical failures of PTRA as a major cause of the muted response of renal function to revascularization in atherosclerotic RAS. As a result of the uncertainty regarding outcomes, several clinical trials, such as Angioplasty and STent for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) (13) and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) (14) trials, are in the process of examining the benefits of revascularization compared to medical treatment alone to improve renal function in these patients.

Additional evidence advances the notion that RAS itself is not the only mechanism affecting the kidney in atherosclerotic renovascular disease. In contrast to patients with fibromuscular dysplasia, the decrease in renal perfusion (15) and function (16) does not correlate with the angiographic degree of stenosis for patients with atherosclerotic RAS. Important support for this observation is derived from the correlation between renal functional outcome and chronic renal damage score, glomerulosclerosis, and interstitial volume in ‘atherosclerotic nephropathy’, or renal pathology in the presence of disseminated atherosclerosis (17). A corollary of this correlation is that the severity of histopathological damage is an important determinant and predictor of renal functional outcome even in the absence of hemodynamically significant RAS (17).

Because renal functional outcomes are only loosely linked to renal arterial patency in atherosclerotic RAS, additional mechanisms must determine renal injury. However, the major factors responsible for renal tissue injury in RAS are yet unidentified. While pre-existing and co-existing risk factors (e.g. aging, renal disease, essential hypertension) likely amplify damage in the stenotic kidney, the decrease in renal perfusion in patients with atherosclerotic RAS exceeds that incurred in age- and treatment-matched patients with fibromuscular dysplasia with a similar degree of stenosis (15). Therefore, additional pathogenic factors inherent to the disease might contribute to renal damage in atherosclerotic RAS.

Factors that aggravate renal disease in atherosclerotic RAS likely involve synergistic interactions among disease mechanisms activated by diffuse atherosclerosis and those triggered by the super-imposed renal arterial obstruction. Maladaptive activation of the renin-angiotensin system as a result of the decrease in renal perfusion pressure as well as by dyslipidemia, circulating atherogenic factors that impact the renal parenchyma distal to the stenosis, and/or hypoxia secondary to renal arterial obstruction and oxidative stress, might all interact to amplify renal functional and structural damage.

Vascular dysfunction in atherosclerotic renovascular disease

Atherosclerotic renovascular disease involves co-existence of hypoperfusion, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular risk factors, which activate mechanisms that promote renal functional impairment and tissue injury. Conversely, some of the humoral factors activated in RAS accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis (18). Several deleterious pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways that have been implicated in progression of renal damage in hypoperfused kidneys may also be activated in the kidney during the evolution of atherosclerosis (19). In both conditions renal functional impairment is initiated by endothelial injury, reduced bioavailability of the vasodilator nitric oxide, and increased activity of vasoconstrictors, all of which are common to both RAS and atherosclerosis. Renal microvessels are susceptible to noxious insults including ischemia, low shear stress, or oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), which compromise the integrity of the endothelium and prompt endothelial cells for early swelling and dysfunction (20). Consequent dysfunction of endothelial cells impairs vascular reactivity, endothelial barrier function, angiogenic capability, proliferative capacity, and migratory properties, and blunts protection from inflammatory cell infiltration. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction in both these milieus is accompanied by increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress. These changes result in predominance of renal vasoconstrictors, enhanced renal vascular tone, and premature senescence.

ROS activate several pathways that modulate renal microvascular function. Taken together, ROS increase renal vascular tone, sensitivity to vasoconstrictors, endothelial dysfunction, and tubuloglomerular feedback that characterize pathophysiological conditions associated with increased oxidative stress (21). The interaction of ROS with nitric oxide decreases bioavailability of the latter, and at the same time results in formation of the pro-oxidant peroxynitrite. These effects combine to impair intra-renal vascular, glomerular, and tubular function (Figure 1). The result of quenched vascular nitric oxide is to limit its buffering effect, thereby allowing intra-renal vasopressors like angiotensin II and endothelin-1 to predominate with vasoconstriction and a decrease in glomerular filtration rate. This mechanism has the potential to impair both renal hemodynamics and function.

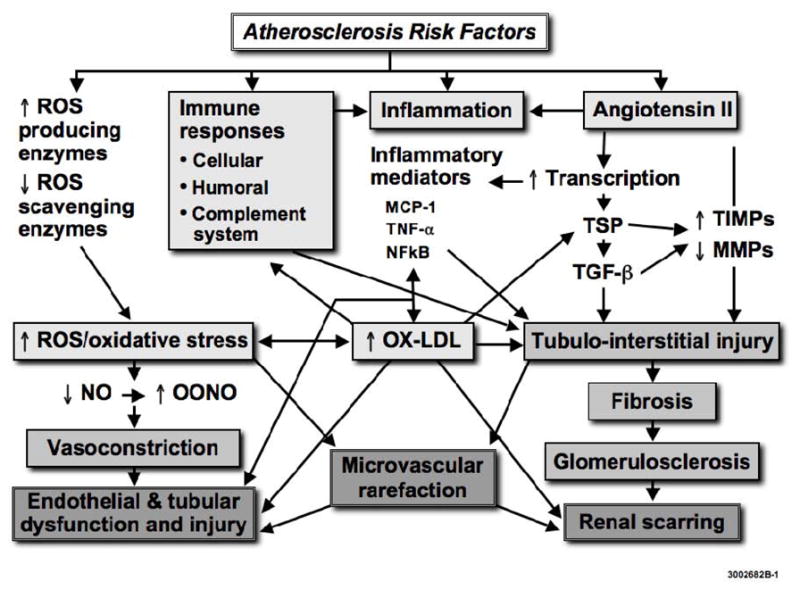

Figure 1.

Interplay of mechanisms by which atherosclerosis might aggravate kidney injury in renal artery stenosis. Angiotensin II and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate the expression of thrombospondin (TSP), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP), leading to a decrease in matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), accumulation of extra-cellular matrix, and fibrosis. Immune responses and inflammatory mediators such as nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, contribute to increase oxidative stress, formation of oxidized LDL (ox-LDL), and fibrosis. ROS also scavenge nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO), thereby inducing endothelial dysfunction and loss of the vasculoprotective effects of NO. Similar mechanisms lead to loss of intra-renal microvessels. Modified with permission from (19).

Since RAS and atherosclerosis are both characterized by increased oxidative stress, their co-existence augments the production of ROS and impairs renal function. Indeed, oxidative stress is increased in stenotic kidneys (22–24), and further exacerbated in the presence of co-existing early atherosclerosis, in association with amplification of renal dysfunction and injury (25, 26). Furthermore, reduced endogenous nitric oxide may interfere with a spectrum of additional activities of the molecule, such as loss of both its anti-thrombotic protection and inhibition of fibrosis-related responses to injury. Similar mechanisms might be involved in increased activity of growth factors and inflammatory mediators observed in RAS, eventuating in renal tissue injury.

Renal structural injury in atherosclerotic renovascular disease

The severity of histopathological damage is an important determinant of renal outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic nephropathy, regardless of the presence of RAS (17). When experimental RAS occurs, renal hypoperfusion leads to a mixture of adaptive responses, tubular and endothelial cell damage and repair events (27). Progressive renal failure can result from glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and/or vascular sclerosis. Glomerulosclerosis is a relatively late event in human RAS and often linked to long duration, pre-existing injury, and exacerbating co-morbid conditions, like dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis (27). Glomerular lesions are initially minimal in experimental models of chronic non-infarcted RAS (27) and observed only with severe stenosis nearing cortical infarction (28, 29). The earliest and most pronounced pathologic features in renal ischemia consist of tubulointerstitial changes (27, 30) that may mediate the progression of renal disease towards irreversible damage. At the early phase of this process cellular activation takes place, as mononuclear cells migrate into the interstitium and myofibroblasts/activated-fibroblasts release soluble products that contribute to inflammation (31). This likely involves activation of inflammatory mediators like the redox-sensitive transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) (32), possibly through ROS release. Apoptosis may also be induced by ROS, and initially serves as a protective mechanism to induce tubular atrophy (33), but can also initiate inflammation and tissue injury (31). However, this phase may still be partly reversible until fibrosis begins (34) and eventuates in permanent parenchymal damage.

Cellular activation in the stenotic kidney elicits release of growth factors and cytokines, with primary roles suggested for angiotensin II, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and endothelin-1 (35), which also use ROS as second messengers. These in turn can stimulate production and activity of growth factors that modulate renal tissue response to ischemia-like collagen deposition, extracellular matrix turnover, fibrosis, and angiogenesis (Figure 1); excessive matrix accumulation finally leads to irreversible scarring. In addition, tubular injury alters the antigenic profile of the epithelial cells, and instigates a cascade of immune responses associated with infiltration of B-lymphocytes, T-lymphocytes, and macrophages. Similar processes accompany initiation of glomerular cell apoptosis, basement membrane thickening, and expansion of the mesangial extracellular matrix, which progress to glomerulosclerosis (36–38). NFκB is a pivotal player in this process, as its target genes include chemokines, adhesion molecules, and anti-apoptotic factors, such as matrix metalloproteinases -2 and -9. Furthermore, NFκB upregulates endothelin-1 expression, and might thus be also involved in vasoconstriction (39). Indeed, proteasome inhibitors, which decrease proliferation and inflammation partly by reducing activation of the NFκB, can improve renal endothelial function (40).

Little is known about molecular mechanisms of renal injury related to atherosclerosis itself in humans, but a series of studies in a pig model with diet-induced hypercholesterolemia, a surrogate for early atherosclerosis, reveal some of the mediators that might be activated at the early stages. Cellular and molecular events involved early in atherogenesis resemble those triggered in other forms of renal disease (19). Similar to RAS, dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis are pro-inflammatory conditions characterized by interstitial inflammatory infiltrates (41), NFkB activation (42), collagen deposition (43), growth factor production, altered matrix turnover (44), tubulointerstitial damage (45), and eventually glomerulosclerosis (46). In fact, it has been long recognized that glomerulosclerosis and atherosclerosis share similar pathophysiological mechanisms (47-50).

Hypercholesterolemia increases the availability of ox-LDL, which is cytotoxic to renal mesangial, epithelial, and endothelial cells, and can promote fibrosis by increasing intra- and extra-cellular matrix protein synthesis, as well as by decreasing its degradation (51). Hence, ox-LDL accelerates the development of fibrosis in the stenotic kidney by amplifying profibrotic mechanisms and disrupting tissue remodeling (Figure 1), alterations that contribute to microvascular remodeling and renal disease progression (26). Notably, angiotensin II stimulates both LDL oxidation and ox-LDL uptake, since it upregulates the expression of its receptor LOX-1 (52). LOX-1 is upregulated in hypercholesterolemia, upregulates the AT1 and its own receptor, and increases ROS production, instigating a cytotoxic cycle (53, 54), since LOX-1 expression is also redox-sensitive. These effects might be exacerbated during co-existence of atherosclerosis and hypoperfusion, and thereby accelerate renal injury. Endothelin-1 (22) and oxidative stress (55) that are abundant in renovascular disease also regulate renal LOX-1 expression. Therefore, concurrent atherosclerosis may contribute to the evolution of renal damage, both directly through deposition of atherogenic and oxidized lipoproteins (56, 57) and indirectly by increasing oxidative stress, since many of these processes, cytokines, and growth factors are redox-sensitive.

An additional important pathway by which atherosclerosis might contribute to renal disease progression includes impeding defense mechanisms that curtail structural damage and interfering with matrix turnover. Renal scarring and tissue remodeling are dynamic processes that involve both synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix, the balance between which appears to be disrupted in several renal diseases. The accumulation of fibroblasts, excess collagen, and other matrix components leads to scar tissue formation. RAS kidneys with or without concurrent HC exhibit upregulated tubular and glomerular expression of pro-fibrotic factors like TGF-β, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1. However, compared to RAS alone, coexistent HC increases the expression of NFkB, attenuates the expression of extra-cellular (matrix-metalloproteinase-2) and intra-cellular (ubiquitin) protein degradation systems (44), and decreases apoptosis (that serves to eliminate damaged cells) in the kidney (26). Early atherosclerosis also induces tubular dysfunction (25) and elicits tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a process shown to participate in several forms of renal disease (58). This suggests a shift in the tissue remodeling process in atherosclerotic RAS favoring tubular injury, matrix accumulation, and interstitial fibrosis (Figure 1).

In addition to tubulointerstitial injury, patients with atherosclerosis exhibit intra-renal microvascular disease leading to vascular rarefaction (27, 34, 59, 60). This process represents an early phase of ischemic renal disease, which may initially produce functional abnormalities and evolves into permanent changes in microvascular structure. This is because prolonged periods of reversible vasoconstriction can cause lasting changes in the microcirculation, the most prominent of which are microvascular remodeling (e.g. an increase in wall/lumen ratio) and rarefaction (reduced number or combined length of peritubular capillaries within vascular beds) (61). Loss (rarefaction) of peritubular capillaries (62) and tubulointerstitial injury are prominent feature in renal ischemia and linked to renal dysfunction (Figure 1). A decrease in oxygen supply upregulates the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, and in turn of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that induces compensatory new vessel formation. However, prolonged or severe increases in oxidative stress may destabilize HIF-1α protein and thereby interfere with tissue repair. Thus, chronic hypoxia itself may restrict compensatory angiogenesis and decrease its efficiency for restoring stenotic kidney perfusion. In addition, atherosclerosis can suppress new vessel formation by upregulating anti-angiogenic factors like thrombospondin, which in turn activates TGF-β, inhibits matrix metalloproteinases, and thereby disrupts matrix turnover (44). Indeed, decreased spatial density of microvessels characterizes stenotic kidneys (24, 63) (Figure 2) and might be caused by decreased expression of HIF-1α and VEGF proteins; both this protein expression and microvascular density can be improved by pro-angiogenic intervention (64). Since microvascular remodeling correlates with renal scarring (65), it may have important implication for renal disease progression in atherosclerotic renovascular disease.

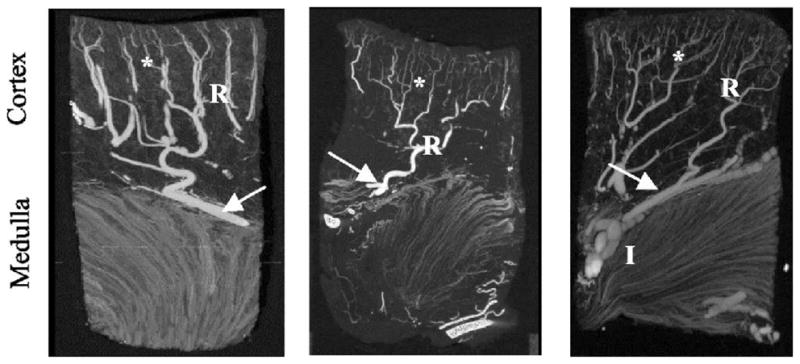

Figure 2.

Tomographic images of the renal microcirculation showing microvascular rarefaction in the stenotic kidney (middle panel) compared to normal pig kidney (left), which was improved in RAS pigs treated with chronic antioxidant supplementation (right). The vessels on the cortex and medulla show interlobar vessels (I), arcuate vessels (arrow), and the branching orders of radial vessels (R) with numerous small vessels (*) in the outer third of the cortex (displayed at 40-μm voxel size). Modified with permission from (24).

What is the role of hypoxia in “ischemic renal disease”?

“Ischemia” refers to impaired blood flow below the level needed to satisfy the metabolic demands of the tissue, presumably leading to tissue hypoxia. While the term “ischemic nephropathy” suggests that impairment of renal function beyond occlusive disease of the main renal arteries results from hypoxia, the contribution of true hypoxia to renal damage in RAS has been controversial (66). Renal oxygen supply is among the highest in the body (Table 1) (67), so that less than 10% of delivered oxygen is needed to maintain renal metabolic needs. Interestingly, in patients with unilateral RAS a decrease in O2 consumption appears to exceed the decrease in renal blood flow, based on the observation that oxygen-saturation in blood from the ischemic kidney is sometimes higher than that from the non-stenotic contralateral kidney (68). This may result from decreased glomerular filtration and tubular sodium reabsorption that reduce oxygen consumption in the stenotic kidney (Figure 3). Hence, one might argue that loss of renal viability is not necessarily related to impaired oxygenation.

Table 1.

The estimated balance of oxygen consumption and delivery in different organs.

| Region or organ | O2 Delivery (mL/min/100g) | Blood flow rate (mL/min/100g) | O2 Consumption (mL/min/100g) | O2 Consumption/O2 delivery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepato-portal | 11.6 | 58 | 2.2 | 18 |

| Kidney | 84.0 | 420 | 6.8 | 8 |

| Outer medulla | 7.6 | 190 | 6.0 | 79 |

| Brain | 10.8 | 54 | 3.7 | 34 |

| Skin | 2.6 | 13 | 0.38 | 15 |

| Skeletal muscle | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.18 | 34 |

| Heart | 16.8 | 84 | 11.0 | 65 |

Modified with permission from (67).

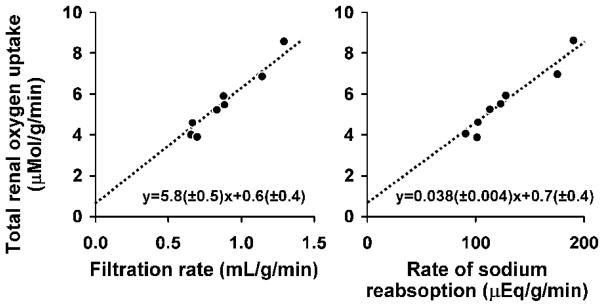

Figure 3.

The relationship between renal oxygen consumption and renal filtration rate (left) and sodium reabsorption rate (right). A decrease in renal metabolic activity is associated with a decrease in total renal oxygen uptake, constituting a mechanism to balance oxygen supply and demand. Modified with permission from (80).

However, recent studies during acute RAS measuring intra-renal tissue oxygenation directly using oxygen electrodes have demonstrated in pigs that while graded decrements in renal blood flow were paralleled by decrements in oxygen delivery and consumption and sustained arterio-venous oxygen balance, regional renal tissue oxygenation declined (medullary more than cortical), supporting the existence of regional tissue hypoxia (69). Similarly, renal cortical PO2 of chronically clipped kidneys is significantly lower than contralateral kidneys in early Goldblatt hypertensive rats (70). Thus, measures of whole kidney oxygen consumption may be insufficient to indicate the presence of localized ischemia and changes in tissue O2 delivery and consumption. These observations are underscored by imaging studies in pigs employing Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that detects tissue deoxyhemoglobin signal, which have shown that BOLD signal of the cortex and the medulla increased during gradual renal arterial occlusion (indirectly implying a decrease in renal oxygenation) (71). Furthermore, BOLD MR studies in kidneys of patients with RAS confirm higher medullary deoxyhemoglobin levels compared to the cortex, although basal BOLD signal varies widely between individuals (72). In patients with high grade RAS but with preserved tissue volume and enhancement, the medullary and cortical BOLD signal are elevated and fall after intravenous furosemide (which inhibits energy-dependent renal transport and oxygen consumption) (72). These observations suggest that viable kidneys may show regional ischemic changes that are associated with tubular transport activity, and are thus attenuated by furosemide.

How, then, is renal vein oxygen saturation preserved or even increased from the stenotic kidney? Important differences in tissue oxygen requirements and delivery exist within regions of the kidney, leaving some areas vulnerable to reduced flow (72). These regional changes in oxygenation may be related to redistribution of sodium reabsorption along the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle’s Loop, shifting of reabsorption from paracellular to transcellular pathways that increase stoichiometric energy requirements, and increased renal arterio-venous oxygen shunting (69).

Renal arterio-venous oxygen shunting has been proposed as a structural antioxidant defense mechanism that prevents PO2 in the renal cortical microcirculation from increasing to hyperoxic levels commensurate with the high delivery of blood to the kidney. Studies in rabbits indicate that fractional extraction of oxygen falls with increasing renal blood flow without concomitant changes in intra-renal PO2, leading the authors to implicate arterio-venous oxygen shunting in regulation of intrarenal oxygenation (73). As much as 50% of inflowing oxygen from blood within preglomerular arterial vessels may undergo diffusional shunting to post-glomerular veins (Figure 4) speculatively preventing production of ROS in what could otherwise become a hyperoxic microenvironment (74). Renal oxygen consumption is also modulated by tubular work, the efficiency of tubular reabsorption (which in turn depends on ROS and nitric oxide), cellular hypertrophy, and possibly vascular wall oxygen consumption as well (75). Interestingly, experimental studies in a remnant kidney model indicate that tubular hypertrophy is associated with tubulointerstitial hypoxia as assessed by pimonidazole and upregulation of hypoxia-responsive genes (76). Conceivably, tubular atrophy in the stenotic kidney might conversely decrease O2 consumption and offset hypoxia. On the other hand, microvascular dysfunction and rarefaction (24, 63, 64), inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis in the stenotic kidney may all decrease the efficiency of tubular reabsorption (69), thereby limiting oxygen supply and diffusion (63). These processes ultimately may result in areas of heterogeneous, yet functionally consequential, intra-renal hypoxia that may not be reflected as a decrease in the whole kidney venous PO2.

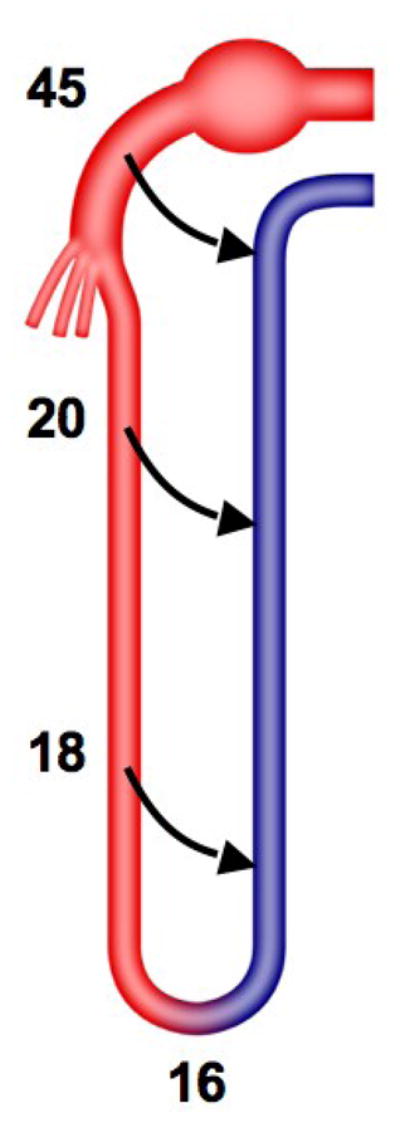

Figure 4.

Arterio-venous oxygen shunting is likely to occur in the kidney, in which a counter-current arrangement allows close proximity of arteries and veins. This might be one of the mechanisms that regulate intra-renal oxygenation. The numbers represent oxygen tension along the nephron (mmHg).

Perspective

Taken together, cumulative evidence suggests that atherosclerosis has the potential to accelerate the detrimental effects of hypoperfusion on renal hemodynamics and function. Concurrent atherosclerosis may promote impairment in renal function and structure in atherosclerotic renovascular disease, and amplify activation of disease mechanisms (e.g. oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis) in the stenotic kidney. Furthermore, it may accelerate irreversible renal injury and scarring, which impede recovery of the atherosclerotic RAS kidney following revascularization. Identification of pathways involved in renal injury progression may assist in development of targeted interventions that preserve the stenotic kidney.

For example, activation of the renin-angiotensin system is a hallmark of renovascular disease and characterizes atherosclerosis as well, but its blockade in RAS is potentially harmful, because of a consequent decrease in glomerular filtration rate. Nonetheless, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are often renoprotective in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, are generally not associated with total loss of filtration, and renal function usually does not further deteriorate during chronic treatment (77). Chronic blockade of oxidative stress pathways by supplementation of antioxidant vitamins E and C improves renal hemodynamics and decreases oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in the experimental ischemic kidney (22, 23, 78). These maneuvers also can restore microvascular architecture (24) (Figure 2). However, the disappointing results of clinical trials argue against indiscriminate use of antioxidants in human disease. More recently, intra-renal administration of progenitor cells has shown promise to improve the function and structure of the kidney subjected to chronic (64) or acute (79) ischemic injury. These observations underscore the urgent need to develop novel anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic strategies to attenuate renal injury.

In summary, elucidation of mechanisms involved in deleterious effects of concurrent atherosclerosis and renal artery stenosis on the kidney can advance our understanding of the pathogenesis of renal injury. Such studies may also be relevant to the effects of atherosclerosis upon other forms of nephropathy associated with ischemia (34).

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by NIH grant numbers HL085307, DK77013, HL77131, and DK73608.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, Cherr GS, Jackson SA, Appel RG, Burke GL, Dean RH. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:443–51. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.127351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, Fujii T, Yamauchi A, Takishita S, Kimura G. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:537–42. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vashist A, Heller EN, Brown EJ, Jr, Alhaddad IA. Renal artery stenosis: a cardiovascular perspective. Am Heart J. 2002;143:559–64. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Ibrahim H, Macleod B, Salem D, Griffith J, Coresh J, Levey A, Sarnak M. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlon PJ, Little MA, Pieper K, Mark DB. Severity of renal vascular disease predicts mortality in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1490–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillay WR, Kan YM, Crinnion JN, Wolfe JH. Prospective multicentre study of the natural history of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Br J Surg. 2002;89:737–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Airoldi F, Palatresi S, Marana I, Bencini C, Benti R, Lovaria A, Alberti C, Nador B, Nicolini A, Longari V, Gerundini P, Morganti A. Angioplasty of atherosclerotic and fibromuscular renal artery stenosis: time course and predicting factors of the effects on renal function. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:1210–7. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safian RD, Madder RD. Refining the approach to renal artery revasularization. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2009;2:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morganti A. Angioplasty of the renal artery: antihypertensive and renal effects. J Nephrol. 2000;13 (Suppl 3):S28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dejani H, Eisen TD, Finkelstein FO. Revascularization of renal artery stenosis in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:752–8. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.17654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Textor SC, Wilcox CS. RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS: A Common, Treatable Cause of Renal Failure? Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:421–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marekovic Z, Mokos I, Krhen I, Goreta NR, Roncevic T. Long-term outcome after surgical kidney revascularization for fibromuscular dysplasia and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. J Urol. 2004;171:1043–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110372.77926.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry S, Ives N, Harding J, Fitzpatrick-Ellis K, Lipkin G, Kalra PA, Moss J, Wheatley K. Angioplasty and STent for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL trial): rationale, methods and results so far. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:511–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Textor SC. Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: overtreated but underrated? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:656–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerman LO, Taler SJ, Textor S, Sheedy PF, Stanson AW, Romero JC. CT-derived intra-renal blood flow in renovascular and essential hypertension. Kidney Int. 1996;49:846–854. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suresh M, Laboi P, Mamtora H, Kalra PA. Relationship of renal dysfunction to proximal arterial disease severity in atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:631–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright JR, Duggal A, Thomas R, Reeve R, Roberts IS, Kalra PA. Clinicopathological correlation in biopsy-proven atherosclerotic nephropathy: implications for renal functional outcome in atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:765–70. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fava C, Minuz P, Patrignani P, Morganti A. Renal artery stenosis and accelerated atherosclerosis: which comes first? J Hypertens. 2006;24:1687–96. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000242388.92225.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chade AR, Lerman A, Lerman LO. The Kidney in Early Atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2005;45:1042–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000167121.14254.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodsky SV, Yamamoto T, Tada T, Kim B, Chen J, Kajiya F, Goligorsky MS. Endothelial dysfunction in ischemic acute renal failure: rescue by transplanted endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F1140–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00329.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnackenberg CG. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of oxygen radicals in the renal microvasculature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R335–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00605.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Herrmann J, Krier JD, Zhu X, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Beneficial Effects of Antioxidant Vitamins on the Stenotic Kidney. Hypertension. 2003;42:605–12. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000089880.32275.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Grande JP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant Intervention Blunts Renal Injury in Experimental Renovascular Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:958–66. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000117774.83396.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu XY, Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Cortical Microvascular Remodeling in the Stenotic Kidney. Role of Increased Oxidative Stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1854–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142443.52606.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Krier JD, Lerman A, Romero JC, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Distinct renal injury in early atherosclerosis and renovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:1165–71. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027105.02327.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Zhu X, Sica V, Napoli C, Sawamura T, Textor SC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Mechanisms of renal structural alterations in combined hypercholesterolemia and renal artery stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1295–301. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000077477.40824.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanley PF. The pathology of chronic renal ischemia. Semin Nephrol. 1996;16:21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran K, Mulhall J, Kelly D, Sheehan S, Dowsett J, Dervan P, Fitzpatrick JM. Morphological changes and alterations in regional intrarenal blood flow induced by graded renal ischemia. J Urol. 1992;148:463–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerman LO, Schwartz RS, Grande JP, Sheedy PF, Romero JC. Noninvasive evaluation of a novel swine model of renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1455–1465. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1071455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greco BA, Breyer JA. Atherosclerotic ischemic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:167–87. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daemen MA, van ‘t Veer C, Denecker G, Heemskerk VH, Wolfs TG, Clauss M, Vandenabeele P, Buurman WA. Inhibition of apoptosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion prevents inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:541–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guijarro C, Egido J. Transcription factor-kappa B (NF-kappa B) and renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;59:415–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gobe GC, Axelsen RA, Searle JW. Cellular events in experimental unilateral ischemic renal atrophy and in regeneration after contralateral nephrectomy. Lab Invest. 1990;63:770–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyrier A, Hill GS, Simon P. Ischemic renal diseases: new insights into old entities. Kidney Int. 1998;54:2–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunley TE, Kon V. Endothelin in ischemic acute renal failure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1997;6:394–400. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino H, Sugiyama H, Kashihara N. Apoptosis and extracellular matrix-cell interactions in kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sodhi CP, Batlle D, Sahai A. Osteopontin mediates hypoxia-induced proliferation of cultured mesangial cells: role of PKC and p38 MAPK. Kidney Int. 2000;58:691–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang DH, Anderson S, Kim YG, Mazzalli M, Suga S, Jefferson JA, Gordon KL, Oyama TT, Hughes J, Hugo C, Kerjaschki D, Schreiner GF, Johnson RJ. Impaired angiogenesis in the aging kidney: vascular endothelial growth factor and thrombospondin-1 in renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:601–11. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uzun O, Demiryurek AT. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors abolish hypoxic vasoconstriction in sheep-isolated pulmonary arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;458:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02761-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chade AR, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Krier JD, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Effects of Proteasome Inhibition on the Kidney in Experimental Hypercholesterolemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1005–1012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stulak JM, Lerman A, Rodriguez Porcel M, Caccitolo JA, Romero JC, Schaff HV, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Renal vascular function in experimental hypercholesterolemia is preserved by chronic antioxidant vitamin supplementation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1882–1891. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman LO, Holmes DR, Richardson D, Napoli C, Lerman A. Chronic antioxidant supplementation attenuates nuclear factor-kappaB activation and preserves endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic pigs. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:1010–8. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eddy AA. Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis in rats with diet-induced hypercholesterolemia. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1139–49. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chade AR, Mushin OP, Xhu X, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Textor SC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Pathways of renal fibrosis and modulation of matrix turnover in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Hypertension. 2005;46:772–779. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000184250.37607.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bentley MD, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Sarafov MH, Romero JC, Pelaez LI, Grande JP, Ritman EL, Lerman LO. Enhanced renal cortical vascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1056–1063. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasiske BL, O’Donnell MP, Schmitz PG, Kim Y, Keane WF. Renal injury of diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in rats. Kidney Int. 1990;37:880–91. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haller H. Calcium antagonists and cellular mechanisms of glomerulosclerosis and atherosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;21:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diamond JR. Analogous pathobiologic mechanisms in glomerulosclerosis and atherosclerosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;31:S29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diamond JR, Karnovsky MJ. Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: analogies to atherosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1988;33:917–24. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keane WF, Kasiske BL, O’Donnell MP. Lipids and progressive glomerulosclerosis. A model analogous to atherosclerosis. Am J Nephrol. 1988;8:261–71. doi: 10.1159/000167599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eddy AA. Interstitial fibrosis in hypercholesterolemic rats: role of oxidation, matrix synthesis, and proteolytic cascades. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1182–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morawietz H, Rueckschloss U, Niemann B, Duerrschmidt N, Galle J, Hakim K, Zerkowski HR, Sawamura T, Holtz J. Angiotensin II induces LOX-1, the human endothelial receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Circulation. 1999;100:899–902. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Napoli C, Lerman LO. Involvement of oxidation-sensitive mechanisms in the cardiovascular effects of hypercholesterolemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:619–631. doi: 10.4065/76.6.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehta JL, Li D. Identification, regulation and function of a novel lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1429–35. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chade AR, Bentley MD, Zhu X, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Niemeyer S, Amores-Arriaga B, Napoli C, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention prevents renal neovascularization in hypercholesterolemic pigs. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1816–25. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130428.85603.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takemura T, Yoshioka K, Aya N, Murakami K, Matumoto A, Itakura H, Kodama T, Suzuki H, Maki S. Apolipoproteins and lipoprotein receptors in glomeruli in human kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 1993;43:918–27. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wheeler DC, Chana RS. Interactions between lipoproteins, glomerular cells and matrix. Mineral Electrol Metab. 1993;19:149–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chade AR, Zhu XY, Grande JP, Krier JD, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin abates development of renal fibrosis in experimental renovascular disease. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1651–1660. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328302833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meyrier A. Renal vascular lesions in the elderly: nephrosclerosis or atheromatous renal disease? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:45–52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/11.supp9.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Textor SC. Ischemic nephropathy: where are we now? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1974–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133699.97353.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levy BI, Schiffrin EL, Mourad JJ, Agostini D, Vicaut E, Safar ME, Struijker-Boudier HA. Impaired tissue perfusion: a pathology common to hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;118:968–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.763730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Basile DP, Donohoe D, Roethe K, Osborn JL. Renal ischemic injury results in permanent damage to peritubular capillaries and influences long-term function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F887–99. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.5.F887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chade AR, Zhu X, Mushin OP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin promotes angiogenesis and prevents microvascular remodeling in chronic renal ischemia. Faseb J. 2006;20:1706–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5680fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chade AR, Zhu X, Lavi R, Krier JD, Pislaru S, Simari RD, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Endothelial progenitor cells restore renal function in chronic experimental renovascular disease. Circulation. 2009;119:547–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang DH, Kanellis J, Hugo C, Truong L, Anderson S, Kerjaschki D, Schreiner GF, Johnson RJ. Role of the microvascular endothelium in progressive renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:806–16. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Textor SC, Wilcox CS. Ischemic nephropathy/azotemic renovascular disease. Semin Nephrol. 2000;20:489–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brezis M, Rosen S, Silva P, Epstein FH. Renal ischemia: a new perspective. Kidney Int. 1984;26:375–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielsen K, Rehling M, Henriksen JH. Renal vein oxygen saturation in renal artery stenosis. Clin Physiol. 1992;12:179–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1992.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Warner L, Gomez SI, Bolterman R, Haas JA, Bentley MD, Lerman LO, Romero JC. Regional decreases in renal oxygenation during graded acute renal arterial stenosis: a case for renal ischemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R67–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90677.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palm F, Connors SG, Mendonca M, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors and nitric oxide sustain oxygenation in the clipped kidney of early Goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:345–51. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Juillard L, Lerman LO, Kruger DG, Haas JA, Rucker BC, Polzin JA, Riederer SJ, Romero JC. Blood oxygen level-dependent measurement of acute intra-renal ischemia. Kidney Int. 2004;65:944–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Textor SC, Glockner JF, Lerman LO, Misra S, McKusick MA, Riederer SJ, Grande JP, Gomez SI, Romero JC. The use of magnetic resonance to evaluate tissue oxygenation in renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:780–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leong CL, Anderson WP, O’Connor PM, Evans RG. Evidence that renal arterial-venous oxygen shunting contributes to dynamic regulation of renal oxygenation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1726–33. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00436.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O’Connor PM, Anderson WP, Kett MM, Evans RG. Renal preglomerular arterial-venous O2 shunting is a structural anti-oxidant defence mechanism of the renal cortex. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:637–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evans RG, Gardiner BS, Smith DW, O’Connor PM. Intrarenal oxygenation: unique challenges and the biophysical basis of homeostasis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1259–70. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90230.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manotham K, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Ohse T, Miyata T, Inagi R, Kurokawa K, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Evidence of tubular hypoxia in the early phase in the remnant kidney model. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000125614.35046.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miyamori I, Yasuhara S, Takeda R. Long-term effects of converting enzyme inhibitors on split renal function in renovascular hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1987;9:629–32. doi: 10.3109/10641968709164235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chade AR, Krier JD, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Breen JF, McKusick MA, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Comparison of Acute and Chronic Antioxidant Interventions in Experimental Renovascular Disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1079–86. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stroo I, Stokman G, Teske GJ, Florquin S, Leemans JC. Haematopoietic stem cell migration to the ischemic damaged kidney is not altered by manipulating the SDF-1/CXCR4-axis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lassen NA, Munck O, Thaysen JH. Oxygen consumption and sodium reabsorption in the kidney. Acta Physiol Scand. 1961;51:371–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1961.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]