Abstract

We have studied the in vivo signaling mechanisms involved in nociceptin/orphanin FQ (Noci)-induced pain responses by using a flexor-reflex paradigm. Noci was 10,000 times more potent than substance P (SP) in eliciting flexor responses after intraplantar injection into the hind limb of mice, but the action of Noci seems to be mediated by SP. Mice pretreated with an NK1 tachykinin receptor antagonist or capsaicin, or mice with a targeted disruption of the tachykinin 1 gene no longer respond to Noci. The action of Noci appears to be mediated by the Noci receptor, a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein–coupled receptor that stimulates inositol trisphosphate receptor and Ca2+ influx. These findings suggest that Noci indirectly stimulates nerve endings of nociceptive primary afferent neurons through a local SP release.

The heptadecapeptide nociceptin/orphanin FQ (Noci) has recently been identified as an endogenous ligand of the opioid receptor-like ORL1 or Noci receptor (Noci-R) (1, 2). Although both Noci and Noci-R are structurally similar to dynorphin A and opioid receptors, respectively (see review ref. 3), low doses of Noci given intrathecally (i.t.) produce hyperalgesia or allodynia (4), whereas moderate doses (i.t.) cause analgesia (5–7). However, the molecular and neuronal pathways involved in Noci-signaling in pain-modulation are not well characterized. Recently we developed a simple and sensitive method to evaluate nociceptive responses to locally applied pain-producing substances (8–10). Using this technique, we have studied the Noci-induced nociceptive responses and their signaling mechanisms in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male ddY mice weighing 20–22 g were used in most of experiments. In some experiments 129SV/J-derived tachykinin 1 gene knockout (tac1−/−) and wild-type (tac1+/+) mice (11) were used. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by The Declaration of Helsinki.

Drugs.

The following drugs were used: Noci (Sawady Technology, Tokyo), substance P (SP; Peptide Institute, Osaka), pertussis toxin (PTX, Funakoshi, Tokyo), MEN-10376 (Research Biochemicals), capsaicin (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto), EGTA (Dojindo Kumamoto, Japan), U-73122 and U-73343 (Funakoshi, Tokyo). CP-96345, CP-96344, CP-99994 and CP-100263 were generously provided by Pfizer. Botulinum toxin A (BoTX) and araguspongine E (xestospongin C) were purified, as reported (12–14). Noci, SP, PTX, EGTA, CP-96345, CP-96344, CP-99994, and CP-100263 were dissolved in physiological saline, MEN-10376 in 3% dimethyl sulfoxide, capsaicin in 1% ethanol and 1% Tween 80 in saline, U-73122, and U-73343 in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide, BoTX in 0.05 M of acetate buffer, and araguspongine E in 0.01% ethanol. Drugs were given by intraplantar (i.pl.) injection in a volume of 2 μl. To apply different doses, one cannula was filled with increasing concentrations of Noci or SP separated by small air spaces. The antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (5′-GGGCTGTGCAGAAGCGCAGA-3′) and its mismatch nucleotide (5′-GGGTCGGTCAGAGACGCAGA-3′) for mouse Noci-R were synthesized (6), freshly dissolved in physiological saline and used for i.t. injection in a volume of 2 μl on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6 the flexor responses were tested.

Evaluation of Nociceptive Flexor Response.

Experiments were performed, as described earlier (8–10). Briefly, mice were lightly anesthetized with ether and held in a cloth sling with their four limbs hanging free through holes. The sling was suspended on a metal bar. All limbs were tied with strings, and three limbs were fixed to the floor, and the fourth one was connected to an isotonic transducer and recorder. Mice were anesthetized with ether and a small incision was made in the surface of right hind-limb planta. Two polyethylene cannulae (0.61 mm in outer diameter) filled with drug solution were connected to a microsyringe. As we used light and soft polyethylene cannulae, they did not fall off the paw during the experiments. As the intensity of flexor responses differs from mice to mice, we used the biggest response among spontaneous and nonspecific flexor responses occurring immediately after cannulation as the maximal reflex. Nociceptive responses were measured after complete recovery (20–30 min) from the light ether anesthesia. Noci or SP injections were given i.pl. every 5 min unless otherwise stated. In some experiments Noci (SP)-induced nociceptive activity was expressed as the ratio of maximal reflex in each mouse, and in other experiments the effects of test drugs were expressed as the ratio of the response observed over the average of two repeated control Noci (or SP)-induced responses in the beginning of experiments. Test drugs affecting Noci (or SP)-responses were given through a second cannula immediately after the second control (Noci- or SP)-response was measured.

Statistical Analysis.

The data were analyzed using Student’s t test after multiple comparisons of the ANOVA. The criterion of significance was set at P < 0.05. All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Peripheral Nociceptive Flexor Responses Produced by Nociceptin and Substance P.

The local application of Noci at 1 fmol into the i.pl. region of the hind limb produced a very short-acting nociceptive flexor response. Stable flexor responses were obtained after repeated Noci challenges at 5–min intervals (Fig. 1A). The mean ± SEM of Noci (1 fmol)-induced responses correspond to a force of 6.75 ± 0.16 g (n = 50), and the response to Noci (0.01 to 10 fmol) was dose-dependent with median effective dose (± SEM) of 0.38 ± 0.08 fmol (n = 6). Similar nociceptive responses were also observed when higher doses of SP (see Fig. 1B) or bradykinin (see ref. 9) was given. The median effective dose for SP in the present experiments was 1.35 ± 0.34 pmol. The wide dynamic range of Noci-induced flexor responses suggest that this animal model should be readily amendable to pharmacological interventions and provide a very useful tool for the in vivo analysis of Noci signaling.

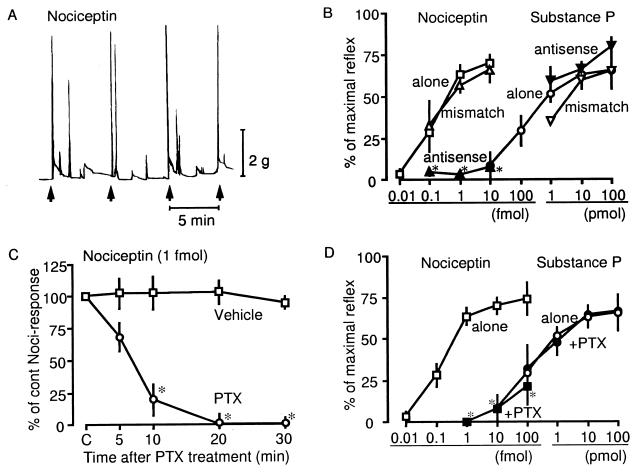

Figure 1.

Receptor- and Gi/o-involvement in Noci-induced flexor responses. (A) A representative trace of Noci-induced flexor responses. Noci (1 fmol) was given i.pl. consecutively every 5 min, as indicated by the arrow. (B) Effects of Noci-R antisense and mismatch oligodeoxynucleotides on Noci- or SP-induced responses at various doses. Results were expressed as % of maximal reflex. (C) Effects of PTX on Noci-induced responses. PTX (10 ng) was given 5 min after the second challenge of Noci as a control. (D) Dose-response curves for Noci or SP in the presence or absence of PTX (10 ng)-treatments. (A–C) Treatments as indicated in the figure were compared with agonist treatment alone. *P < 0.05. Other details were as described under Materials and Methods. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from separate five experiments.

Noci-Induced Flexor Responses Are Mediated by the Noci-Receptor and PTX-Sensitive G Proteins on Peripheral Nerve Endings.

To determine the role of the Noci-specific Noci-R in Noci-induced flexor responses, we injected mice i.t. with Noci-R antisense oligonucleotides, or mismatch controls (each 10 μg), three times over a period of six days. As shown in Fig. 1B, flexor responses were abolished in antisense-treated animals, whereas the i.t. injection of mismatch nucleotide had no effect. The Noci-R mismatch had also no effect on SP-induced nociceptive responses, whereas the antisense treatment did not increase the SP response (Fig. 1B).

Administration of 10 ng of PTX rapidly attenuated and completely abolished Noci-induced flexor responses 20 min after the PTX treatment (Fig. 1C). Application of 1 ng of PTX reduced flexor responses to 35.5 ± 12.7% of control values 20 min after PTX treatment (n = 4). Treatments with 10 ng of PTX markedly attenuated Noci-induced responses at all doses used. In contrast, SP-induced flexor responses were not affected by PTX treatment (Fig. 1D).

Involvement of Local SP Release in Noci-Induced Nociceptive Responses.

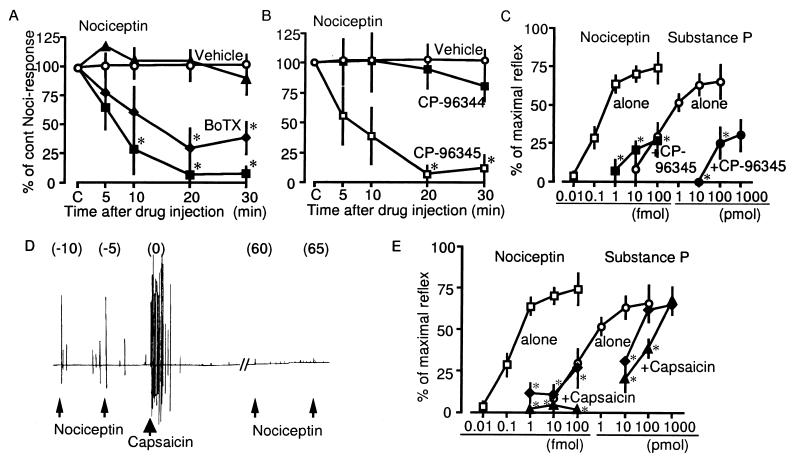

The Noci-induced responses were rapidly attenuated by an i.pl. injection of botulinum toxin A (BoTX), which is known to block neurotransmitter release (15), in a dose-dependent manner in ranges of 1 to 100 fg (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, Noci-induced responses were also abolished by 10 pmol of CP-96345, an NK1 antagonist, but not by 10 pmol of CP-96344, an inactive derivative (16), as shown in Fig. 2B. In the presence of 10 pmol of CP-96345, the dose-response curves of Noci and SP were shifted to the right (Fig. 2C). To further clarify the subtype-specificity of tachykinin receptors, other tachykinin antagonists were tested. As shown in Table 1, Noci-induced responses were abolished by CP-99994, a very specific NK1 antagonist, but not by CP-100263, an inactive derivative of CP-99994 (17), or by MEN-10376, a specific NK2 antagonist (18). These findings suggest that SP but not substance K is involved in Noci-induced responses.

Figure 2.

Effects of various treatments related to SP release in Noci-induced responses. (A) Noci-induced responses in the presence of BoTX at 0 ng (vehicle, ○), 1 fg (▴), 10 fg (⧫), and 100 fg (■). Details of BoTX-treatments were as in the case with PTX (see legend of Fig. 1C). (B) Noci-responses in the presence of vehicle (○), CP-96344 at 10 pmol (■) and CP-96345 at 10 pmol (□). (C) Dose-response curves of Noci- and SP-induced responses in the absence and presence of 10 pmol of CP-96345. (D) A representative trace of the loss of Noci-induced responses after the capsaicin-challenge. Noci and capsaicin were given at doses of 1 fmol and 2 μg, respectively. (E) Dose-response curves of Noci- and SP-induced responses after the treatments with and without capsaicin (⧫, 0.2 μg; ▴, 2 μg). Other details are given the legend of Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Effects of tachykinin receptor antagonists on nociceptin-induced responses

| Compound | % of cont Noci-responses | (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 102.73 ± 12.43 | 6 |

| CP-96345 (10 pmol) | 7.05 ± 7.05* | 5 |

| CP-96344 (10 pmol) | 94.24 ± 15.70 | 5 |

| CP-99994 (1 pmol) | 0* | 4 |

| CP-100263 (1 pmol) | 87.14 ± 3.77 | 4 |

| MEN-10376 (100 pmol) | 97.80 ± 6.09 | 4 |

P < 0.05, vs. Vehicle.

Application of capsaicin, which is known to induce the release and eventually the depletion of SP from small-diameter nociceptive primary afferent neurons (19, 20) first resulted in sustained nociceptive flexor responses for several minutes, and subsequently lead to the loss of Noci-induced responses (Fig. 2D). The attenuation of Noci-induced responses by 2 μg of capsaicin was complete for a wide range of Noci-doses (1 to 100 fmol). On the other hand, SP-responses were only partially inhibited by capsaicin treatment (Fig. 2E). Together, these findings suggest that Noci-induced responses were mediated through SP-release. SP-responses, however, appeared to involve the direct stimulation of primary afferent neurons, as previously reported (10).

Possible Involvement of Inositol Trisphosphate and Ca2+ Influx Into Nerve Endings in Noci-Induced Responses.

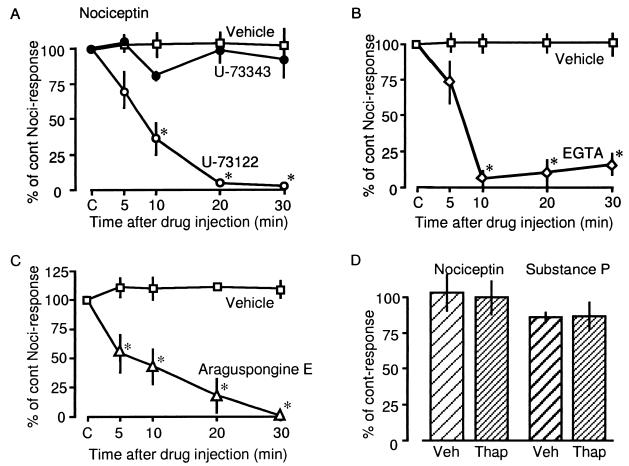

Noci-induced responses were markedly inhibited by i.pl. injection of 10 pmol of U-73122, a phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor, but not U-73343, an inactive derivative (21), as shown in Fig. 3A. Maximal inhibition was observed 20 min after the injection, indicating that PTX, BoTX and NK1 antagonists have similar kinetics. The Ca2+ chelating agent EGTA (2 nmol) also markedly inhibited flexor responses with a maximum effect 10 min after injection (Fig. 3B). As SP-induced flexor responses were also inhibited by PTX, BoTX, and EGTA treatment, the cellular mechanisms involved in Noci-induced flexor responses, e.g., Noci-induced SP-release or activation of nerve endings by SP, seem to involve the activation of PLC and Ca2+ influx (10).

Figure 3.

Effects of various compounds related to Ca2+ signaling on Noci-induced responses. In all experiments 1 fmol of Noci was given as indicated in the figure. Drugs used here were 10 pmol of U-73122 or U-73343 (A), 2 nmol of EGTA (B) and 10 pmol of araguspongine E (C). (D) Noci (1 fmol) or SP (10 pmol)-responses 20 min after the thapsigargin (100 pmol)-treatment. Other details are in the legend of Fig. 1.

To investigate whether inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptors in the plasma membrane are involved in Ca2+ influx, we used araguspongine E (xestospongin C), which has recently been shown to be a good membrane-permeable InsP3 receptor antagonist (22). As shown in Fig. 3C, Noci-induced responses were markedly inhibited by 10 pmol of araguspongine E. On the other hand, SP- and Noci-induced responses were not affected by thapsigargin at 100 pmol (i.pl.) that is known to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores and was found to block the histamine release by compound 48/80 (Inoue et al. unpublished data).

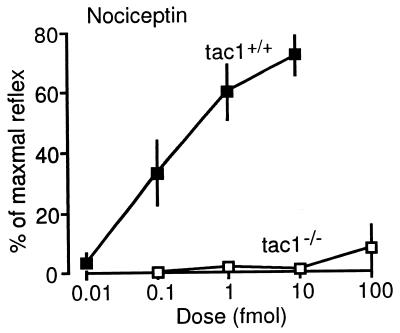

Loss of Noci-Induced Nociceptive Responses in Mice with a Targeted Mutation of Tachykinin 1 Gene.

The responses to Noci were similar in the wild-type (tac1+/+) and the ddY mice used in the other experiments (Figs. 4 and 1B). These responses were completely lost in tac1−/− mice, which cannot produce SP and substance K (11), at all Noci doses tested (0.1 to 100 fmol, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Dose-response curves for Noci in mice with a targeted mutation of tachykinin 1 gene. Details are in the legend of Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

The peripheral analgesia test used in these studies has several advantages over many other assays of analgesia (8–10). Firstly, this method is sensitive enough to assess very weak and short-acting nociceptive responses induced by a local application of extremely small amounts of pain-producing substances, such as bradykinin and SP. It is evident that these treatments cause only a very transient response, in contrast to other widely used pain tests such as the formalin test (23) or the acetic acid-writhing test (24). Secondly, the nociceptive responses in this test appeared to involve relatively simple molecular and neuronal mechanisms, in contrast to other nociceptive tests, which use strong and sustained chemical stimuli release several endogenous pain-producing substances, such as bradykinin, SP, somatostatin, histamine, and glutamate (25–27), and rely on complex behavioral responses. Thirdly, as the peripheral nerve endings are far distant from the cell body in the dorsal root ganglion, the site of actions of various pharmacological reagents affecting such behavioral responses could be confined to nerve endings. In addition, taking into account that primary afferent neurons are bipolar cells, the in vivo signaling at the peripheral side of such neurons also could be expected on the other, central side.

Here we demonstrate that Noci induced nociceptive flexor responses in a dose-dependent manner over a wide range of doses. We propose that the flexor responses are mediated by the Noci-R on nerve endings of primary afferent neurons, because they were abolished by local application of PTX or by i.t. injection of Noci-R-antisense oligonucleotides (Fig. 1 B–D). It is unlikely that the injected antisense oligonucleotides reached to the peripheral planta of the hind limbs and affected peripheral cells, such as mast cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, or vascular cells. It is more likely that the antisense treatment inhibited the Noci-R synthesis in primary afferent neurons, because Noci-R gene expression has been detected in the dorsal root ganglion (28). The involvement of Noci-R in Noci-induced responses has been also confirmed in mice lacking Noci-R gene (Inoue et al. in preparation).

Under physiological conditions, Noci may be released from peripheral nerve endings of sensory afferents. Prepronociceptin gene expression has been found in dorsal root ganglia (29) and is increased in Adjuvant-arthritic rats (30). On the other hand, Noci may be released from non-neuronal peripheral cells, such as mast cells, macrophages or lymphocytes, because prepronociceptin gene expression in non-neuronal tissue including ovary (31), spleen, leukocytes and fetal kidney (32) has been reported.

The striking inhibition of Noci-induced flexor responses by local application of tachykinin receptor antagonists, BoTX and capsaicin, suggests that these responses are dependent on a release of SP from peripheral nerve endings. This hypothesis was strongly supported by the finding that Noci-induced responses were completely abolished in tac1−/− mice that cannot produce SP. The potency of Noci-induced responses was extremely high. Noci was 10,000-fold more potent than SP (Fig. 1B) and 1,000-fold more potent than bradykinin (9). Although the molecular and neuronal mechanisms underlying the nociceptive flexor-responses remain to be elucidated, the efficiency of the different post receptor mechanisms could explain the differences in potency of Noci, SP, and bradykinin. The Noci-R is functionally coupled to PTX-sensitive G proteins (33), whereas both NK1 and bradykinin (B2) receptors are coupled to PTX-insensitive G proteins, such as Gq/11 (34, 35). It has been shown that the stoichiometry of receptor-Gq/11 coupling is quite poor, compared with receptor-Gi/o coupling (36). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that unknown other Noci-induced mechanisms potentiate the effects of endogenously released SP.

We have previously reported on our analysis of the molecular events involved in SP-induced flexor responses (10). Because SP-induced nociceptive responses were blocked by a local application of EGTA or tetrodotoxin, we have proposed that SP-induced Ca2+ influx into peripheral nerve endings of nociceptive primary afferent neurons can produce action potentials. As the SP-responses were also blocked by a PLC inhibitor, we postulated that the Ca2+ influx may be regulated through the PLC products, InsP3 or diacylglycerol. In the present study, Noci-induced responses were also abolished by PLC inhibitor and EGTA. These findings are consistent with the notion that Noci may release SP from peripheral nerve endings. Most importantly, we have demonstrated that Noci-induced responses were also abolished by araguspongine E (xestospongin C), a marine alkaloid that is an allosteric InsP3 receptor antagonist (22). Furthermore we have shown that both SP and Noci-induced flexor responses were not affected by thapsigargin that is known to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores (37) and to abolish the compound 48/80-induced histamine release from mast cells (Inoue et al. unpublished data). These findings suggest that PLC activation triggers Ca2+ influx through InsP3 receptors in the plasma membranes of nerve endings, rather than Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores. This hypothesis is consistent with a recent report that InsP3 gates Ca2+ influx into nerve endings in experiments with resealed vesicles of presynaptic plasma membrane preparations (38). In these studies Gi1-coupled (kyotorphin) receptor was found to gate Ca2+ influx through an InsP3 formation, and there was no significant InsP3-mediated Ca2+ mobilizing effect in permeabilized synaptosomes. Therefore it is possible that InsP3-gated Ca2+ influx may be involved in both, Noci-induced SP release and SP-mediated activation of nerve endings. It remains to be determined whether diacylglycerol-activated protein kinase C mechanisms are also involved in downstream Noci signaling.

In summary, we have shown that in vivo signaling of Noci-induced pain is dependent upon release of SP in peripheral nerve endings of primary nociceptive afferent neurons. This finding should greatly facilitate the analysis of the role of nociceptin in acute and chronic pain and may open novel possibilities for pharmacological interventions.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this study were supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Japan and a grant from The Naito Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Noci

nociceptin/orphanin FQ

- Noci-R

Noci receptor

- SP

substance P

- BoTX

botulinum toxin A

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- PLC

phospholipase C

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- i.pl.

intraplantar

- i.t.

intrathecal(ly)

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

A commentary on this article begins on page 10354.

References

- 1.Meunier J-C, Mollereau C, Toll L, Suaudeau C, Moisand C, Alvinerie P, Butour J-L, Guillemot J-C, Ferrara P, Monsarrat B, Mazarguil H, Vassart G, Parmentier M, Costentin J. Nature (London) 1995;377:532–535. doi: 10.1038/377532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinscheid R K, Nothacker H-P, Bourson A, Ardati A, Henningsen R A, Bunzow J R, Grandy D K, Langen H, Monsma F J, Jr, Civelli O. Science. 1995;270:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meunier J-C. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuda-Ashitaka E, Tachibana S, Houtani T, Minami T, Masu Y, Takeshima H, Sugimoto T, Ito S. Mol Brain Res. 1996;43:96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu X-J, Hao J-X, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. NeuroReport. 1996;7:2092–2094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King M A, Rossi G C, Chang A H, Williams L, Pasternak G W. Neurosci Lett. 1997;223:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian J-H, Xu W, Mogil J S, Grisel J E, Grandy D K, Han J-S. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:676–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokuyama S, Inoue M, Fuchigami T, Ueda H. Life Sci. 1998;62:1677–1681. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue M, Nakayamada H, Tokuyama S, Ueda H. Neurosci Lett. 1997;236:60–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00760-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue, M., Tokuyama, S., Nakayamada, H. & Ueda, H. (1998) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Zimmer A, Zimmer A M, Baffi J, Usdin T, Reynolds K, Konig M, Palkovits M, Mezey E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2630–2635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugii S, Sakaguchi G. Infect Immun. 1975;12:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.6.1262-1270.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi M, Kawazoe K, Kitagawa I. Chem Pharm Bull. 1989;37:1676–1678. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi M, Miyamoto Y, Aoki S, Murakami N, Kitagawa I, In Y, Ishida T. Heterocycles. 1998;47:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray P. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1993;29A:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snider R M, Constantine J W, Lowe J A, III, Longo K P, Lebel W S, Woody H A, Drozda S E, Desai M C, Vinick F J, Spencer R W, et al. Science. 1991;251:435–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1703323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet J, Kucharczyk N, Robineau P, Lonchampt M, Dacquet C, Regoli D, Fauchere J L, Canet E. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;310:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maggi C A, Giuliani S, Ballati L, Lecci A, Manzini S, Patacchini R, Renzetti A R, Rovero P, Quartara L, Giachetti A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;257:1172–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canavan D, Graff-Radford S B, Gratt B M. J Orofac Pain. 1994;8:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiura A, Sakamoto Y. Neurosci Lett. 1987;76:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleasdale J E, Thakur N R, Gremban R S, Bundy G L, Fitzpatrick F A, Smith R J, Bunting S. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:756–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gafni J, Munsch J A, Lam T H, Catlin M C, Costa L G, Molinski T F, Pessah I N. Neuron. 1997;19:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubuisson D, Dennis S G. Pain. 1977;4:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh P P, Junnarkar A Y, Rao C S, Varma R K, Schridhar D R. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1983;5:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarson K E, Krause J E. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1189–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray C W, Cowan A, Larson A A. Pain. 1991;44:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90135-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohkubo T, Shibata M, Takahashi H, Inoki R. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:1261–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wick M J, Minnerath S R, Lin X, Elde R, Law P Y, Loh H H. Mol Brain Res. 1994;27:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito Y, Maruyama K, Kawano H, Hagino-Yamagishi K, Kawamura K, Saido T C, Kawashima S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15615–15622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andoh T, Itoh M, Kuraishi Y. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:1809. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mollereau C, Simons M-J, Soularue P, Liners F, Vassart G, Meunier J-C, Parmentier M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8666–8670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nothacker H P, Reinscheid R, Mansour A, Henningsen R A, Ardati A, Monsma F J, Jr, Watson S J, Civelli O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8677–8682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Z J, Fan G H, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Wu Y L, Jiang L Z, Zhu Y, Pei G, Ma L. NeuroReport. 1997;8:1913–1918. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald S G, Dumas J J, Boyd N D. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2909–2916. doi: 10.1021/bi952351+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etscheid B G, Villereal M L. J Cell Physiol. 1989;140:264–271. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pang I H, Sternweis P C. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18707–18712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takemura H, Hughes A R, Thastrup O, Putney J W., Jr J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12266–12271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueda H, Tamura S, Fukushima N, Katada T, Ui M, Satoh M. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2891–2900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-02891.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]