Abstract

For the past 15–20 years, the intracellular delivery and silencing activity of oligodeoxynucleotides have been essentially completely dependent on the use of a delivery technology (e.g. lipofection). We have developed a method (called ‘gymnosis’) that does not require the use of any transfection reagent or any additives to serum whatsoever, but rather takes advantage of the normal growth properties of cells in tissue culture in order to promote productive oligonucleotide uptake. This robust method permits the sequence-specific silencing of multiple targets in a large number of cell types in tissue culture, both at the protein and mRNA level, at concentrations in the low micromolar range. Optimum results were obtained with locked nucleic acid (LNA) phosphorothioate gap-mers. By appropriate manipulation of oligonucleotide dosing, this silencing can be continuously maintained with little or no toxicity for >240 days. High levels of oligonucleotide in the cell nucleus are not a requirement for gene silencing, contrary to long accepted dogma. In addition, gymnotic delivery can efficiently deliver oligonucleotides to suspension cells that are known to be very difficult to transfect. Finally, the pattern of gene silencing of in vitro gymnotically delivered oligonucleotides correlates particularly well with in vivo silencing. The establishment of this link is of particular significance to those in the academic research and drug discovery and development communities.

INTRODUCTION

It has long been believed that oligodeoxynucleotides, in the absence of a transfection method such as lipofection, cannot be efficiently used as silencing molecules for in vitro studies. This notion was accepted because oligonucleotide polarity renders them impermeable to hydrophobic cell membranes (1). Further, the observation by microscopy of bright nuclear staining after cellular microinjection or lipo-transfection with fluorescent oligonucleotides has been considered the sine qua non for RNAse H-mediated gene silencing (2–6). Thus, the screening of libraries of sequence-complementary oligomers produced by ‘mRNA walking’ for optimally active molecules has virtually always relied on carrier-dependent cellular transfection. This contrasts with the in vivo situation, where oligonucleotide silencing has traditionally not depended on carrier-dependent transfection.

We have developed a process (called ‘gymnosis’) that does not require the use of any transfection reagent or any additives to serum whatsoever, but rather takes advantage of the normal growth properties of cells in tissue culture in order to promote productive oligonucleotide uptake. This robust method permits the sequence-specific silencing of multiple targets in a large number of cell types in tissue culture, both at the protein and mRNA level, at concentrations in the low micromolar range. Optimum results were obtained with locked nucleic acid (LNA) phosphorothioate gap-mers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

The 518A2 mycoplasma-free human melanoma cell line was a kind gift of Dr Volker Wachek (University of Vienna, Austria). Cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin G sodium and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Melanoma cells (591.8, 1000 and 1000.36) were isolated from patients with advanced melanomas by Dr J. Kirkwood (University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA), expanded and frozen. These lines were grown in RPMI (Invitrogen) supplemented as above with the inclusion of 1% MEM. HT-1080 fibrosarcoma and Namalwa Burkitt’s lymphoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA), and were grown in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin G sodium and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Huh-7 human hepatoma cells were grown in DMEM (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Both media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM Glutamax, (Invitrogen), 25 µg/ml gentamicin and 1× nonessential amino acids (Sigma). Stock cultures of all cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Materials

The anti-Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Dako (Carpinteria, CA, USA). The anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody was from Sigma. The anti-poly(ADP-ribosyl)polymerase (PARP) monoclonal, anti-pro-caspase-3 monoclonal, anti-Bcl-xL polyclonal, anti-Mcl-1 polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-PKC-α monoclonal antibody was purchased from Neo Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, USA). The antisurvivin polyclonal antibody was purchased from Novus Biological (Littleton, CO, USA). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Invitrogen. A list of the oligomers employed is presented in Table 1.

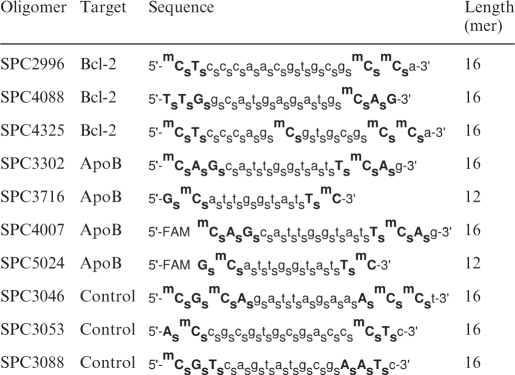

Table 1.

List of the oligomers employed

|

LNA-modified riboses are given in bold capital letters; whereas small letters indicate deoxyriboses. s, Phosphorothioate; m, C5-methylcytosine; FAM, 5′-fluorescein covalent conjugate.

Gymnotic delivery of oligonucleotides

Adherent cells were seeded at low plating density in complete media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) the day before the experiment in 6-well plates, so that they would just attain confluence on the final day of the experiment. The day after plating, oligonucleotides dissolved in PBS were added and mixed. Nonadherent Namalwa cells were seeded at a density of 250 000 cells per well in 4 ml complete media in a 6-well plate. The LNA oligonucleotides were used at a final concentration of 10 µM for these cells. The total incubation time before cell lysis and protein isolation was usually 6 or 10 days at 37°C.

Western blot analysis

Cells treated with oligonucleotides were washed in PBS and then extracted in lysis buffer at 4°C for 1 h. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14 000g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). Aliquots of cell extracts, containing 25–50 µg of protein, were resolved by sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and then transferred to Hybond ECL filter paper (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). After treatment with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies, enhanced chemiluminescence was performed. The typical margin error for a western blotting is at least 20–25%.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured and treated in LabTek chamber slides (Nunc, Naperville, IL, USA), and treated gymnotically with fluoresceinated LNA oligonucleotides for 1, 3 and 6 days. For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. Cells were then incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature to block nonspecific binding of the antibodies, followed for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with the anti-GW182 primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted in the ratio 1:100 in PBS containing 1% BSA. After washing three times for 10 min, rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as secondary antibody (1:100) for detecting anti-GW182. The cells were then washed and mounted using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) prior to microscopic analysis. Images were acquired using an Olympus confocal microscope.

Isolation of RNA and RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 518A2 cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and quantitated by ultraviolet absorption. RNA was reverse-transcribed using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) reactions based on the Super-ScriptTM One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum® Taq (Invitrogen). Bcl-2 was amplified using 1 µg of total RNA. The forward primer was 5′-GGTGCCACCTGTGGTCCACCTG-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-CTTCACTTGTGGCCCAGATAGG-3′. The Bcl-2 amplicon was 459 bp. The primers 5′-GAGCTGCGTGTGGCTCCCGAGG-3′, forward, and 5′-CGCAGGATGGCATGGGGGAGGGCATACCCC-3′, reverse, designed to amplify a 246-bp fragment of β-actin were used to normalize for RNA concentration. The RT–PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNA from Namalwa cells was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse transcription reaction was carried out with random decamers, 0.5 μg total RNA and the M-MLV RT enzyme from (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to protocol. First-strand cDNA was subsequently diluted 10 times in nuclease-free water before addition to the real-time PCR reaction mixture. mRNA quantification of Bcl-2 and GAPDH genes were done using standard TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems). A 2-fold total RNA dilution series from untreated Namalwa cells served as standard to ensure a linear range (Ct versus relative copy number) of the amplification. The Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR instrument was used for amplification.

In vivo studies in mice

These experiments were performed according to the principles stated in the Danish law on animal experiments and were approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Ministry of Justice, Denmark. Female NMRI mice were treated intravenously with 0.9% saline or the LNA oligonucleotides as described at doses of 5 mg/kg/day for three consecutive days, with each group comprising five animals. Animals were sacrificed 24 h after the last dose and liver tissue was dissected and placed in RNA Later stabilization reagent (Qiagen) until further analysis. Total RNA was purified using the Qiagen spin columns according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Subsequently, target mRNA downregulation was quantitated by quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), as previously described.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Gymnotic delivery produces gene silencing

Our initial studies employed 518A2 melanoma cells, a line which is not chemo-sensitized by Bcl-2 silencing (7). We embedded these cells in 3D collagen I gels, and then treated them with 2.5–5 µM SPC2996, a 16-mer phosphorothioate oligonucleotide targeted to the codons 1–6 of the Bcl-2 mRNA. The oligonucleotide also contains two LNA moieties at the 5′ and one base upstream from the 3′ molecular termini (Table 1). These substitutions increase the Tm of the mRNA–DNA duplex by ∼4–6°C/base modification, as well as virtually eliminating 3′, 5′-exonuclease digestion (8–11). After 6 days of continuous culture, the cells were isolated by digestion of the matrix by collagenase type I. After western blotting, substantial (>90%) silencing of Bcl-2 protein expression versus control was observed (data not shown). To the best of our knowledge, it has heretofore not been possible to produce gene silencing in 3D gels when particulates were employed.

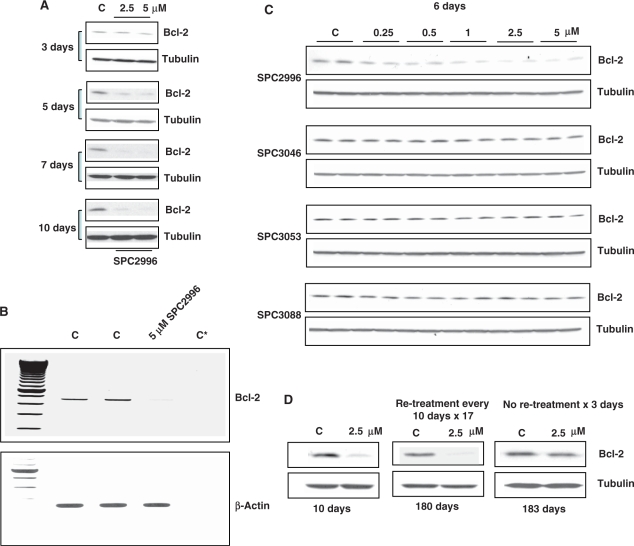

Because the oligomers were delivered ‘naked’ (gymnos in Greek), i.e. without conjugates or transfectants, we have named this process gymnotic delivery. Subsequent experiments were performed in plastic wells in the absence of collagen I, and cells were plated at an initial density such that they would become confluent either by 6 or 10 days. The optimal time for maximum Bcl-2 protein and mRNA silencing by gymnotic delivery in 518A2 cells was found to be 6–10 days (Figure 1A) and 3–5 days (Figure 1B), respectively. Gymnotic delivery of numerous control oligonucleotides to 518A2 melanoma cells did not produce any Bcl-2 protein silencing, demonstrating the sequence specificity of the gymnotic process (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Gymnotic delivery leads to long-term Bcl-2 silencing in 518 A2 melanoma cells. (A) Time course of Bcl-2 protein silencing in 518A2 melanoma cells after gymnotic delivery of SPC2996. Maximum protein silencing was observed after ∼6–7 days for SPC2996. C, untreated control. (B) RT–PCR evaluation of Bcl-2 mRNA levels in 518A2 melanoma cells demonstrating silencing after 6 days in the gymnotic delivery experiment in Figure 1A. C, untreated control; C*, single primer only. (C) Western blots in 518A2 melanoma cells demonstrating silencing of Bcl-2 protein by gymnotic delivery (6 days) of the sequence-specific anti-Bcl-2 phosphorothioate LNA gap-mer SPC2996. Three control oligomers with scrambled sequence, of which one (SPC3053) has identical chemistry to SPC2996, were inactive. (D) Iterative re-addition of SPC2996 (2.5 µM) produces long-term silencing. 518A2 melanoma cells were treated with SPC2996 at a plating density to ensure that the cells were confluent only by Day 10, and then re-plated at that density in the presence of 2.5 µM oligomer. This process was repeated after 10 additional days. Seventeen repetitions were performed. Bcl-2 protein silencing was continuously maintained after 180 consecutive days. However, if the oligomer was removed after 180 days, baseline levels of Bcl-2 protein were restored after 3 days.

Gymnotic silencing is relatively slow compared with lipofection-mediated silencing, where a standard 4 h of treatment with SPC2996 and 3 days incubation are required for maximal mRNA and protein silencing. (Also unlike lipofection, in which particulate matter precipitates on the cells being transfected, a uniform, defined oligonucleotide concentration in the treatment media is present during gymnosis). If, after 10 days of treatment by SPC2996, cells were re-plated in complete media at the original density and re-treated with SPC2996, silencing was maintained for a further 10 days, until the experiment was terminated when cellular confluence was attained. This procedure was repeated every 10 days for 17 consecutive times, and continuous Bcl-2 protein silencing was achieved for SPC2996 for >180 days in the absence of any carrier (Figure 1D). However, when SPC2996 was removed from the media after 10 days of gymnotic delivery to 518A2 cells, Bcl-2 protein expression returned to 50% of the levels of baseline expression in 24 h, and to 100% in ∼72 h. This was also the case after 180 days of continuous Bcl-2 silencing, demonstrating that the silencing did not occur at the level of cellular DNA (Figure 1D). However, phosphodiester SPC2996 (i.e. SPC2996 with no phosphorothioate linkages), with or without two LNA modifications at the 3′ and 5′ molecular termini, did not silence Bcl-2 protein expression in 518A2 cells after 10 days of gymnotic delivery (data not shown). This, possibly, is due at least in part to its degradation by endonuclease activity.

Gene silencing by gymnotic delivery is a general phenomenon

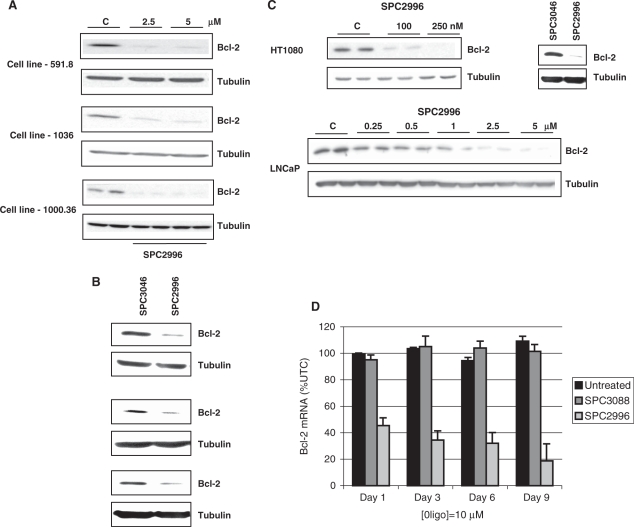

Gymnotic delivery of SPC2996 leading to Bcl-2 protein and mRNA silencing could be demonstrated in multiple cell lines. Because of different growth rates, the plating densities of each cell line were determined so that confluence was achieved only at either 6 or 10 days. Efficient silencing (Figure 2A and B) was observed in 591.8, 1000.36, 1036, 333.1 and 201.2 melanoma cells, PC3 and LAPC-4 prostate cancer cells, Huh-7 hepatoma cells (Figure 5A) and CaCo2 colon cancer cells, with essentially the identical dose dependency as seen in 518A2 cells (Supplementary Figure S1; and data not shown). HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells were very sensitive to gymnotic silencing. The IC50 of Bcl-2 silencing by SPC2996 was ∼100 nM (Figure 2C, top). LNCaP cells, which are notoriously difficult to transfect with lipidic particulates without extensive apoptosis, responded to gymnotic delivery of SPC2996 with IC50 of Bcl-2 silencing also ∼1 µM (Figure 2C, bottom), and minimal if any cytotoxicity. Treatment with multiple control oligomers revealed no change in Bcl-2 expression in any cell line (Figures 1C, 2B and C; and data not shown). In contrast, A375 melanoma cells and SV40-transfected human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) and primary HUVEC cells were completely refractory with respect to Bcl-2 silencing mediated by gymnotic delivery, although not to lipofection (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Gymnotic delivery and silencing is observed in many cell lines. (A) Silencing of Bcl-2 protein expression in the 591.8, 1036 and 1000.36 melanoma cell lines by 2.5 and 5 µM SPC2996. Cells were treated for 10 days by gymnotic delivery before western blotting was performed. C, untreated control. (B) Separate experiments were performed to examine silencing of Bcl-2 protein expression in 591.8, 1036 and 1000.36 melanoma cell lines by 5 µM SPC2996 and the scrambled control oligomer SPC3046. Cells were treated for 6 days by gymnotic delivery before western blotting was performed. (C) Top: gymnotic delivery (10 days) and differential silencing of Bcl-2 protein expression in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells by SPC2996. To the right, separate experiments were performed to examine gymnotic silencing of Bcl-2 (6 days) by SPC2996 and the scrambled control oligomer SPC3046; bottom: gymnotic delivery and silencing (10 days) of Bcl-2 protein expression in LNCaP cells, which can be accomplished with minimum toxicity, as compared with lipofection. (D) In vitro effects of the gymnotic delivery of SPC2996 on the expression of the Bcl-2 mRNA in Namalwa Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. qPCR analysis of Bcl-2 mRNA expression was performed after exposure to SPC2996 or SPC3088, the control oligomer (10 µM, final concentrations) for the indicated times. qPCR values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 5.

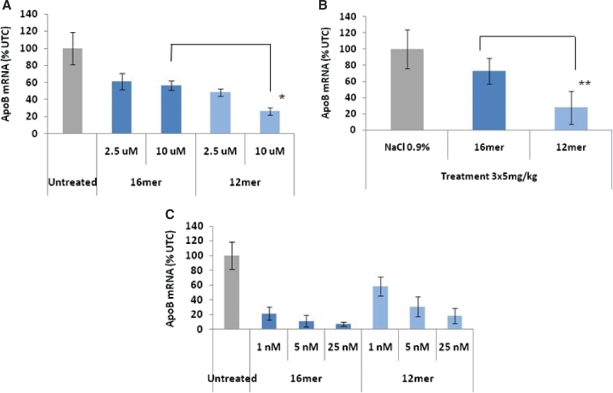

In vitro gymnotic delivery and silencing correlates with in vivo gene silencing. (A) Increased potency of an anti-ApoB 3′,5′-end-capped LNA–phosphorothioate 12-mer gap-mer (SPC3716) versus a 16-mer (SPC3302) after 6 days of in vitro gymnotic delivery to Huh-7 cells. ApoB mRNA silencing data are presented as the average ± SD (n = 3; *P < 0.0001 by Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances). (B) In vivo silencing of intra-hepatic ApoB mRNA expression in female NMRI mice after intravenous delivery (5 mg/kg i.v., Days 0, 1 and 2), demonstrating the increase in potency for the 12-mer versus the 16-mer. Data are presented as the average ± SD (n = 3; **P < 0.02 by Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances). (C) In vitro lipofection (Lipofectamine 2000) of the 12-mer and 16-mer anti-ApoB oligomers into Huh-7 human hepatoma cells, demonstrating the increased potency of the latter compared with its 12-mer counterpart. In contrast to the in vitro gymnotic delivery data, these results are inversely correlated with the in vivo data. Data are presented as the average ± SD (n = 3).

In Namalwa B cells, whose growth is anchorage independent, and which are notoriously resistant to lipofection, gymnotic delivery of the Bcl-2-targeted oligomer SPC2996 led to an 80% decrease in Bcl-2 mRNA expression after 6 days, while no silencing by a control oligomer was seen (Figure 2D). Gene silencing by gymnotic delivery was also efficiently accomplished in multiple cell lines by both anti-survivin and anti-HIF-1α oligomers (518A2 and 1000.36 melanoma cells; data not shown), both of which are LNA phosphorothioate oligonucleotides with equal length and design as SPC2996. No silencing was observed with a scrambled version of the anti-HIF-1α oligomer. Dose dependencies were similar to what was observed for SPC2996.

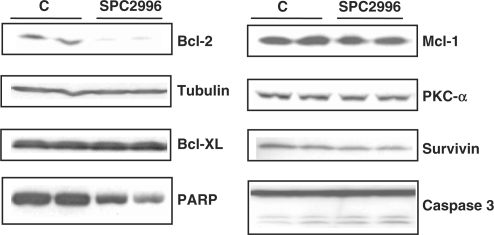

Target-specific effects of gymnotic delivery

It has been previously demonstrated (12,13) that the lipids (e.g. lipofectin and oligofectamine) employed in oligonucleotide transfection can, in some cell lines, induce marked gene changes that may result in early apoptosis. This is particularly true in 518A2 melanoma cells, where lipofection of SPC2996 effectively silences Bcl-2, but also simultaneously causes PARP-1 cleavage and pro-caspase-3 cleavage to caspase-3 (14). We examined the silencing of other Bcl-2 and apoptosis-related targets after 6 days of Bcl-2 silencing by SPC2996 in 518A2 melanoma cells. There were no changes in the levels of expression of Bcl-xL, p21, PKC-α, Mcl-1 or tubulin proteins. PARP-1 and pro-caspase 3 were not cleaved (Figure 3). Levels of survivin protein fluctuated unpredictably from baseline to elevated, depending on the particular experiment, and are thus considered to be epiphenomenal.

Figure 3.

Off-target effects after gymnotic delivery. Off-target effects of the gymnotic silencing of Bcl-2 by 2.5 µM SPC2996 in 518A2 melanoma cells (6 days). As seen in these western blots, no changes in the expression of Bcl-xL, tubulin, Mcl-1, PKC-α or survivin proteins were observed. Furthermore, unlike after lipofection of SC2996, Bcl-2 silencing was not associated with either PARP-1 or pro-caspase-3 cleavage.

The cellular internalization of 5′-FAM-SPC2996 in 518A2 melanoma cells was determined by flow cytometry after 6 days of gymnotic delivery, and compared with lipofection. After 6 days, a single Gaussian-shaped peak in the histogram of fluorescence channel number versus number of cell sorted was observed (Supplementary Figure S2), in sharp contrast with the three peaks seen after lipotransfection, where the peak with the highest channel number corresponded to the bright nuclear staining customarily seen by fluorescence microscopy. In contrast, very little nuclear fluorescence, as opposed to cytoplasmic fluorescence, was observed at any time after gymnotic delivery of 5′-FAM-SPC2996, a molecule that produces >95% Bcl-2 silencing in 518A2 cells (Figure 4). This observation is in sharp distinction to the widely held belief that intense nuclear staining is required for gene silencing (2–6). Further, examination of the nuclear (lipofection) and cytoplasmic (gymnotic delivery) fluorescence of this molecule after fluorescence photobleaching revealed rapid recovery of fluorescence in the nucleus, but almost no recovery in the cytoplasm, indicating a strong interaction of the oligomer with intracytoplasmic components (data not shown).

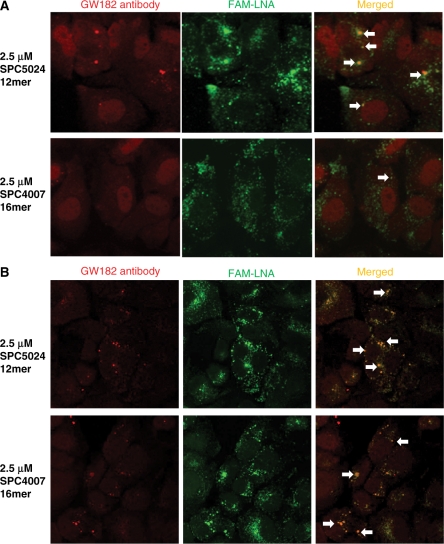

Figure 4.

Co-localization of LNA oligonucleotides with gw182, a GW/P body marker. Confocal microscopic imaging of Huh-7 cells after gymnotic delivery of either a 12-mer (SPC5024) or a 16-mer (SPC4007) anti-ApoB 5′-FAM-3′, 5′-end-capped LNA phosphorothioate gap-mer. After 1 day (A) or 3 days (B) of delivery, cells were fixed and stained with an anti-gw182 primary antibody and visualized with a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. After image merging, the oligomers were observed co-localizing with the GW/P body marker. The 12-mer accumulated more rapidly than the 16-mer after 1 day, but after 3 days of gymnotic delivery, the accumulation in the GW/P bodies are approximately equivalent.

Gymnotically delivered oligonucleotides apparently localize to P-bodies

An anti-Apo-B 16-mer (5′-FAM-SPC4007) (15) or 5′-FAM-SPC5024, a 12-mer truncated variant, was gymnotically delivered to Huh-7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells for 1 and 3 days each (Figure 4A and B, respectively). The cells were then labeled with a GW/P-body-specific antibody targeted to the GW182 protein; it thus detects the cytoplasmic site of the RNA silencing machinery (16,17). The apparent co-localization of the 12-mer oligomer with the GW182 protein was observed after 1 day of gymnotic delivery, but only after 3 days for the 16-mer. In addition, the more rapid kinetics induction of GW/P body formation by the 12-mer versus the 16-mer after gymnotic delivery correlated with increased ApoB mRNA silencing in vitro (Figure 5A).

Gymnotic in vitro silencing correlates with in vivo silencing

Given the former in vitro requirement for delivery adjuvants, it has always been deemed paradoxical that in vivo silencing by oligonucleotides proceeded in the absence of transfection reagents. We treated female NMRI mice intravenously with SPC3302 (16-mer anti-ApoB) or SPC3716 (12-mer anti-ApoB) at doses of 5 mg/kg/day × 3 days; hepatic mRNA was isolated and subjected to qRT-PCR (Figure 5B). The decline in ApoB mRNA expression was 2.5-fold greater for the 12-mer versus the 16-mer, although the rate of plasma clearance of the two oligomers was virtually identical (10). In contrast, when the anti-ApoB 16-mer or the 12-mer was lipofected into Huh-7 cells in vitro, the extent of dose-dependent mRNA silencing favored the 16-mer (Figure 5C). Almost identical in vitro and in vivo results were found with an anti-HIF-1α oligomer with the same gap-mer design; the in vivo potency was predicted by the in vitro gymnotic, but not by the transfection-mediated, silencing data.

In retrospect, what we now call gymnotic silencing has been previously observed with thiophosphoramidate oligomers (18), but to our knowledge it has never been recognized as a general delivery principle. Moreover, LNA gap-mers are not the only chemistry active in gymnosis, 2′-deoxy, 2′-fluoro, β-d-arabinonucleic acid (FANA) phosphorothioate gap-mers (19) are also active. Less expensive, unmodified phosphorothioate oligonucleotides are, in general, not active, with the exception of G3139 [a.k.a genasense, oblimersen (20)], an 18-mer targeted to the same region of the Bcl-2 mRNA as SPC2996, although with relatively decreased potency versus SPC2996. Some 2′-O-methyl modified phosphorothioate oligomers show activity, but rules governing gymnosis for this class of molecule have not yet emerged. Our preliminary results suggest that uncharged oligonucleotides (e.g. peptide and morpholino nucleic acids) are not active.

In toto, our data demonstrate that in vitro silencing by the gymnotic delivery of LNA antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, which we have demonstrated in multiple cell lines, with several targets, and in 3D collagen I gels, can be highly efficient and produce far less toxicity than standard lipofection techniques. Further, the long-accepted dogma that elevated nuclear levels of oligonucleotide is a requirement for silencing has been shown to be incorrect. In addition, as the experiments comparing the 16-mer and 12-mer variants of anti-ApoB oligomers demonstrated, in vitro gymnotic silencing may be linked with and be a better predictor of in vivo silencing efficacy than lipofection. Because of the elimination of toxic lipids and all other transfection reagents, we thus believe that the expansion of this simple, accessible method will prove to be paradigm shifting in the area of antisense oligonucleotide research.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: NCI R01 CA108415 and Santaris to CAS.

Conflict of interest statement. C.A.S. received research funding from and is a scientific advisor to Santaris (Copenhagen, DK). J.L., B.R.H., H.O., T.K., J.W., M.H. and A.H. are employees of Santaris.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhtar S, Basu S, Wickstrom W, Juliano R. Interactions of antisense DNA oligonucleotide analogs with phospholipid membranes (liposomes) Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5551–5559. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walder R, Walder J. Role of RNAse H in hybrid-arrested translation by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5011–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcusson E, Bhat B, Manoharan M, Bennett F, Dean N. Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides dissociate from cationic lipids before entering the nucleus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2016–2023. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher T, Terhorst T, Cao X, Wagner R. Intracellular disposition and metabolism of fluorescently-labeled unmodified and modified oligonucleotides microinjected into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3857–3865. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moulds C, Lewis J, Froehler B, Grant D, Huang T, Milligan J, Matteucci M, Wagner R. Site and mechanism of antisense inhibition of C-5 propyne oligonucleotides. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5044–5053. doi: 10.1021/bi00015a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan W, Wagner R. The development of C-5 propyne oligonucleotides as inhibitors of gene function. In: Stein C, Krieg A, editors. Applied Antisense Oligonucleotide Technology. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benimetskaya L, Lai J, Wu S, Hua E, Khvorova A, Miller P, Stein CA. Relative Bcl-2 independence of drug induced cytotoxicity and resistance in 518A2 melanoma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:8371–8379. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koshkin A, Singh S, Nielsen P, Rajwanshi R, Meldgaard M, Olsen C, Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation, and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3607–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Nielsen P, Koshkin A, Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis and high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chem. Commun. 1998:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Wengel J. Universality of LNA-medicated high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chem. Commun. 1998:1247–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch T, Rosenbohm C, Hansen HF, Hansen B, Straarup EM, Kauppinen S. Locked nucleic acid: properties and therapeutic aspects. In: Kurreck J, editor. Therapeutic Oligonucleotides. Cambridge: RSC Publishing; 2008. pp. 103–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhtar S, Benter I. Toxicogenomics of non-viral drug delivery systems for RNAi: potential impact on siRNA-mediated gene silencing activity and specificity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:164–182. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omidi Y, Hollins A, Benboubetra M, Drayton R, Akhtar S. Toxicogenomics of non-viral vectors for gene therapy: a microarray study of lipofectin- and oligofectamine-induced gene expression changes in human epithelial cells. J. Drug. Target. 2003;11:311–323. doi: 10.1080/10611860310001636908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai JC, Benimetskaya L, Khvorova A, Wu S, Hua E, Miller P, Stein CA. Phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides and G3139 induce apoptosis in 518A2 melanoma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch T, Oerum H. Locked nucleic acid. In: Crooke S, editor. Antisense Drug Technology. 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2008. pp. 519–562. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakymiw A, Lian S, Eystathioy T, Li S, Satoh M, Hamel JC, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. Disruption of GW bodies impairs mammalian RNA interference. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1267–1274. doi: 10.1038/ncb1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen GL, Blau HM. Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:633–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikmen ZG, Wright WE, Shay JW, Gryaznov SM. Telomerase targeted oligonucleotide thio-phosphoramidates in T24-luc bladder cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;104:444–452. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari N, Bergeron D, Tedeschi A, Mangos M, Paquet L, Renzi P, Damha M. Characterization of antisense oligonucleotides comprising 2′-deoxy, 2′-fluoro-beta-D-arabinonucleic acid (FANA); specificity, potency and duration of activity. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2008;1082:91–102. doi: 10.1196/annals.1348.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein C, Wu S, Voskresenskiy A, Zhou J, Shin J, Miller P, Benimetskaya L. G3139, an anti-Bcl-2 antisense oligomer that binds heparin-binding growth factors and collagen I, alters in vitro endothelial cell growth and tubular morphogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:2797–2807. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.