Abstract

Hsmar1 is a member of the mariner family of DNA transposons. Although widespread in nature, their molecular mechanism remains obscure. Many other cut-and-paste elements use a hairpin intermediate to cleave the two strands of DNA at each transposon end. However, this intermediate is absent in mariner, suggesting that these elements use a fundamentally different mechanism for second-strand cleavage. We have taken advantage of the faithful and efficient in vitro reaction provided by Hsmar1 to characterize the products and intermediates of transposition. We report different factors that particularly affect the reaction, which are the reaction pH and the transposase concentration. Kinetic analysis revealed that first-strand nicking and integration are rapid. The rate of the reaction is limited in part by the divalent metal ion-dependent assembly of a complex between transposase and the transposon end(s) prior to the first catalytic step. Second-strand cleavage is the rate-limiting catalytic step of the reaction. We discuss our data in light of a model for the two metal ion catalytic mechanism and propose that mariner excision involves a significant conformational change between first- and second-strand cleavage at each transposon end. Furthermore, this conformational change requires specific contacts between transposase and the flanking TA dinucleotide.

INTRODUCTION

DNA transposons are not as numerous as the retrotransposons, which constitute a major fraction of the genome in mammals. Nevertheless, DNA transposons are almost ubiquitous and have colonized all branches of the tree of life. If judged by the breadth of its phylogenetic distribution, the mariner family is one of the most successful groups of DNA transposons, having been found in almost all animal genomes in which they have been sought (1).

DNA transposons, such as mariner, have an unusual life cycle thought to depend on frequent horizontal transfer into new hosts (2,3). Horizontal transfer is followed by a burst of transposition in the newly invaded genome, followed by a gradual decline in activity, brought about by several different factors. First of all, there is probably an intrinsic limit on the maximum rate of transposition that can be achieved as the number of copies of the element increases: it appears that the increase in transposase concentration, caused by amplification of the transposon, may cause a net decrease in transposition. This phenomenon is called overproduction inhibition (OPI). Furthermore, as different copies of the element acquire inactivating mutations over time, mutant transposases will impair the activity of the wild-type transposase by dominant-negative complementation. Finally, active transposase protein will be titrated by the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of defective copies that retain the transposase binding activity (4). All the three mechanisms are proposed to cause a decrease in transposition, eventually causing the vertical inactivation of the elements. In consequence, DNA transposons have a narrow window of activity following genome invasion, and most organisms therefore contain only inactive copies of DNA transposons.

The Hsmar1 transposon is one of the youngest DNA transposons in the human genome (5–7). It appeared in the primate lineage ∼58 million years ago and was probably active until ∼37 million years ago. During this time, about 200 copies of the full-length element were produced, along with several thousand copies of an 80-bp MITE that we refer to as MiHsmar1 (mini-Hsmar1) (5,6,8). One copy of the Hsmar1 transposase was domesticated when it was fused to a histone H3 methylase gene (5). This gene, called SETMAR, is under purifying selection and appears to be a bona fide component of the human genome (6). The SETMAR protein (sometimes also called METNASE) is expressed in many tissues, and although several activities have been demonstrated, its precise function remains unclear (9,10).

All of the Hsmar1 elements in the human genome have mutations that inactivate the transposase. The first attempt to resurrect the activity of Hsmar1 was to express the transposase domain of the SETMAR protein (8). Transposition events were detected using a very sensitive genetic assay, but the protein was barely active. A further successful attempt was made when the sequence of an ancestral transposase gene was reconstructed using phylogenetic analysis of various Hsmar1 copies (11). When expressed, this sequence provided an active transposase that we will henceforth refer to simply as Hsmar1 transposase.

We are interested in mariner transposition because it appears to use a different biochemical mechanism from most other families of cut-and-paste transposons (12,13). Most DDE (aspartate-aspartate-glutamate) family cut-and-paste transposases use a single-active site to cleave both strands of DNA at the transposon end via a DNA–hairpin intermediate [(14–18) and references therein]. There are exceptions to this paradigm, such as the heteromeric Tn7 transposase. In this case, the transposase subunit cuts the first strand at the transposon end and joins it to the target site, while the second strand is cut by a protomer related to the type II restriction endonucleases (19). The mariner family was expected to conform to the DNA–hairpin paradigm because it encodes a homomeric transposase. However, the hairpin intermediate has been excluded for mariner transposition and the mechanism of cleavage remains unknown (20).

In the hairpin mechanism the first strand is cleaved by hydrolysis. The 3′-OH then takes the place of the water in the active site and the second strand is cleaved by a direct transesterification reaction. In the absence of crystal structures of the intermediates it is unclear exactly how this is achieved. However, the hairpin mechanism does provide a partial explanation of how DNA strands of opposite polarity are cleaved while minimizing the conformational changes required in the active site (21).

In the absence of a hairpin intermediate, mariner transposase must cleave the two strands of the DNA at each transposon end by sequential hydrolysis reactions. Cleavage of the first and second strands at each transposon end may be performed either by the repeated action of a single active site (the one subunit mechanism), or by the sequential action of two active sites belonging to different transposase monomers (the two subunit mechanism). These models describe only the number of active sites required to cleave the two strands of DNA at each transposon end: they are not meant to imply the overall stoichiometry of the active complex, which may contain subunits engaged in a purely structural role. In the single subunit mechanism, the active site would have to nick DNA strands of opposite polarity. To our knowledge, this would be unprecedented except for the unrelated BfiI restriction endonuclease, in which the active site is formed at the dimer interface (22). In the two subunit mechanism, the first subunit would have to move away from the cleavage site to allow access to the second subunit. In either case, a significant conformational change is probably required between first- and second-strand cleavage (12,21).

Before Hsmar1, three mariner family transposons had been studied in vitro: Himar1, Mos1 and Mboumar1 (13,23,24). Although experiments with these elements provided significant insight into the molecular mechanism of the reaction, technical difficulties have precluded detailed biochemical analysis. We have worked with all three elements and found that transposition activity is low at physiological pH (24,25) (Takac,M. and R.C., unpublished data). At higher pH, transposon excision increases, but this is accompanied by a decrease in integration and, in some cases, the appearance of an activity that causes non-specific DNA degradation (Takac,M. and R.C., unpublished data).

We have now completed an exploratory analysis of the Hsmar1 reaction in vitro. We find that up to 100% of the substrate can be converted into product under ideal conditions, and that the DNA degrading activity that affects other related transposases is absent. This provides a mariner transposition system that clearly reproduces the full range of products and intermediates previously observed in other cut-and-paste elements such as Tn10 and Tn5. The clarity of the Hsmar1 in vitro reaction reveals some simple mechanistic insights, and provides important directions for future work.

We find that when the flanking TA dinucleotides, typical of mariner insertions, are mutated to TG the reaction stalls after the first nick. This corresponds to the conformational change postulated to be required between first- and second-strand cleavage. We also show that physiological pH is sub-optimal for transposition, and that the nicked and single-end break (SEB) intermediates accumulate at this pH. The nicked intermediate corresponds to the transition between first- and second-strand cleavage just mentioned above. Since the effects of changing pH are usually mediated by the ionization of amino acid side chains, it may therefore be possible, in the future, to isolate transposase mutations that provide improved activity at physiological pH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents were generally of the best quality available. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma or BDH Laboratory Supplies. Enzymes were from New England Biolabs or Roche Applied Science. DNA manipulations using commercially available enzymes were done according to manufacturer’s recommendations. All cloned PCR products were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Media and bacterial strains

Bacteria were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) media at 37°C. The following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin (Amp), 100 µg/ml; kanamycin (Kan), 50 µg/ml; and chloramphenicol (Cm), 50 µg/ml. The following Escherichia coli strains were used: RC5024 (identical to DH5α) endA1 hsdR17 (rk-mk-) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 d(lacIZYA-argF) U169deoR (phi80dlacd(lacZ)M15); RC5085 = S17.1, RP4-2-Tc::Mu aph::Tn7 recA [SmR] λpir and RC5042 = BL21, E. coli B F- dcm ompT hsdS (rB- mB-) gal.

Plasmids

The gene encoding the reconstructed ancestral version of the Hsmar1 transposase as reported by Miskey and colleagues (11) was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli, chemically synthesized (BioS&T, Canada) and cloned into the pMAL-c2x expression vector between EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites to create pRC880. Standard transposition reactions used the donor plasmid pRC650, a pBluescript-based plasmid in which identical 30 bp Hsmar1 transposon ends (with flanking TA dinucleotides) were cloned as inverted repeats on either side of the kanamycin resistance cassette originally derived from IS903. This provided a 1.7-kb transposon and a 3-kb plasmid backbone. Plasmids pRC824 and pRC704 were reported previously (8). pRC824 is similar to pRC650 except that the 1.4-kb transposon is flanked by symmetrical 5′-TG dinucleotides. The in vitro hop assay used pRC704 as transposon donor and pACYC184 (chloramphenicol and tetracycline resistant) as a target. pRC704 encodes a 2.3-kb kanamycin-resistance Hsmar1 transposon and a 0.8-kb plasmid backbone encoding the R6K conditional origin of replication. The 2D gel analysis was performed with the plasmid pRC1105 which is similar to pRC650 except that filler DNA has been added to increase the size of the transposon and backbone to 2.3 kb and 4.2 kb, respectively. This was done to provide a donor plasmid that was identical in size to that used in the previous 2D gel analysis of Tn10 products. This in turn allowed a straightforward comparison of the products.

Transposase expression and purification

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring pRC880 were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium containing ampicillin. The culture was diluted in the ratio 1:100 in fresh LB medium with selection and grown to mid-log phase (OD600 0.5) and made 1 mM in isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to induce expression of Hsmar1 transposase. After 2 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in HSG buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mM EDTA and 10% glycerol). The cells were lysed in a French press and centrifuged at 25 000g for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto an amylose resin column (New England Biolabs). The column was washed several times with HSG buffer and the protein eluted with HGS buffer plus 10 mM maltose. Fractions containing MBP transposase were pooled and diluted 4-fold in buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM EDTA and 5% glycerol), loaded onto a MonoS HR5/5 column (Amersham Pharmacia), and eluted with a 20-ml gradient of 0.05–1 M NaCl. The fractions containing MBP transposase were pooled and aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Standard in vitro transposition reaction

Unless stated otherwise, a 50 µl transposition reaction contained 1 µg transposon donor plasmid (pRC650), 0.1–0.2 µg of transposase in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT and 2.5 mM MgCl2. The stock solution of transposase was diluted in the reaction buffer as required, and was always the last component added to the reaction mixture. After incubating for 24 h at 37°C reactions were made 20 mM in EDTA, 0.1% SDS and heated at 75°C for 30 min. DNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation, and 40% of each reaction was analyzed by overnight electrophoresis at 2.7 V/cm on a TBE-buffered 1.1% agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide (0.3 µg/ml) and either photographed on a transilluminator or recorded on an FLA 2000 phosphorimager (Fujifilm). ImageGauge 4.21 software (Fujifilm) was used to quantify the bands. Quantification was also performed using the Cyber Green stain, but the linear response range was less with ethidium bromide and quantification with this stain was abandoned. The standard buffer was also used for the pH titration in Figure 2. The pH was adjusted after all of the components except transposase had been added to the mixture. Addition of the transposase did not affect the final pH as the stock solution was diluted 2000-fold in the final reaction.

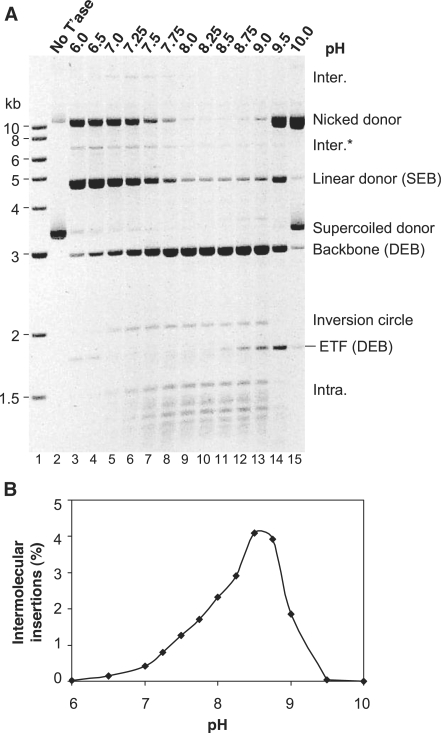

Figure 2.

The effect of pH on Hsmar1 transposition. (A) Hsmar1 transposition reactions were carried out at the indicated pH values. A photograph of an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel is shown. Inter., intermolecular transposition into an unreacted (circular) donor plasmid; Inter.*, the linear product of intermolecular transposition into the linear form of the donor plasmid; the IC is the simplest form of intramolecular integration product as illustrated in Figure 1A; Intra., topologically complex intramolecular insertion products also illustrated in Figure 1A. The plasmid backbone is an end product of the reaction and is used to quantify transposon excision from the donor. The circular ‘Inter.’ intermolecular product was identified after purification from the gel. Individual clones of these molecules were recovered by transformation in E. coli, and the size and structure of a representative selection were analyzed by restriction mapping and nucleotide sequencing. The linear topology of the ‘Inter.*’ product was assigned from the gel in Figure 3. Its position in the present gel is consistent with the size expected for a transposon insertion into a linear donor plasmid. The ‘Intra.’ intramolecular products were identified in Figure 3 (see text for details). (B) The in vitro hop assay for intermolecular transposition was performed at the indicated pH values.

In vitro hop assay

The in vitro hop strategy has been described previously (24). The assay was performed under the standard reaction conditions for Hsmar1 transposition described above. The reaction (20 µl) contained 43 ng pRC704 transposon donor and 112 ng of the pACYC184 dimer as target (final concentration of each plasmid 1 nM). Unless stated otherwise, the transposase was of 10–15 nM. After 24 h at 37°C, reactions were stopped as described above and extracted with phenol–chloroform. DNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation and resuspended in TE buffer. One tenth of the reaction was transformed into DH5α competent cells. After transformation, 1/100 of the mixture was plated on chloramphenicol. The number of colonies provided a measure of the total amount of target DNA recovered. The remainder of the transformation mixture was plated on chloramphenicol plus kanamycin, and the number of colonies was used to quantify the proportion of the target plasmids that had received a transposon insertion.

2D gel electrophoresis

The 2D gel electrophoresis was performed as described previously (26). Briefly, the products of an in vitro transposition reaction containing 0.5 µg of transposon donor (pRC1105) were electrophoresed on a 0.65% agarose gel. After electrophoresis at 1.7 V/cm for 17 h, the lane containing the sample to be analyzed was cut from the gel and turned perpendicular to the direction of electrophoresis. The gel for the second dimension, containing 0.95% agarose and 0.5 µg ethidium bromide per millilitre, was poured at 60°C and allowed to cool. The second dimension was electrophoresed at 3.6 V/cm for 13 h. The gel was stained with CYBR Green I (Invitrogen) and recorded on a FLA 2000 phosphorimager (Fujifilm).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Hsmar1 transposase purification and in vitro assays

A gene encoding the amino acid sequence of the reconstituted ancestral Hsmar1 transposase protein was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli and chemically synthesized. This gene was expressed as a fusion with the maltose binding protein affinity-tag, and purified using amylose affinity-resin and an ion exchange step (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). The purity of the protein was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Supplementary Figure S1A). The protein was also analyzed by size exclusion chromatography on a calibrated Superdex 200 column (Supplementary Figure S1B and C). The MBP-transposase fusion protein (83 kDa) eluted at the volume expected for a protein of 200 kDa. This indicates that the purified protein is probably a dimer. This is consistent with previous experiments carried out with the related Mos1 transposase (20,27).

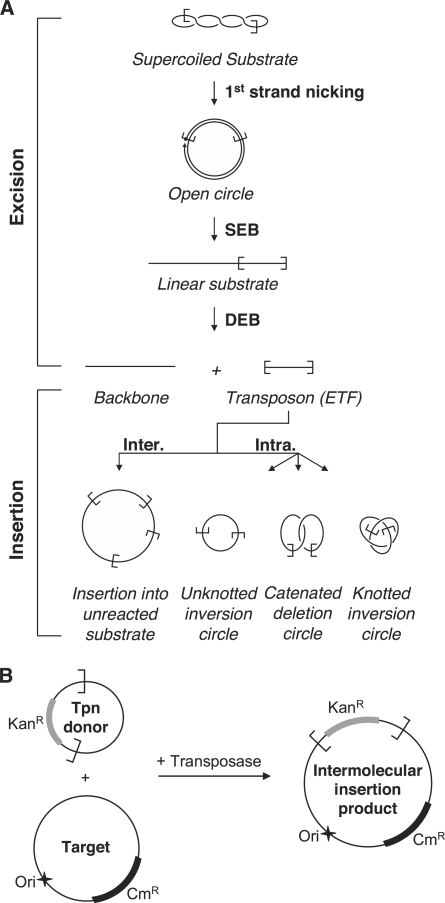

A schematic diagram for an in vitro cut-and-paste transposition reaction using a supercoiled plasmid as the transposon donor is illustrated in Figure 1A. Sequential cleavage of the DNA strands at each transposon end separates the transposon from the donor backbone. Transposition targets may be intermolecular (Inter.) or located within the transposon itself (Intra.). Intermolecular insertions may target any DNA present in the reaction, such as unreacted donor plasmid (as illustrated). Intramolecular targets generate a series of transposon circles, which may be knotted or catenated if supercoils have been trapped between the target site and the transposon end [for details see (26)].

Figure 1.

In vitro Hsmar1 transposition assays. (A) A schematic representation of the different steps of a mariner transposition reaction using a supercoiled plasmid as the transposon donor. First strand nicking at one transposon end generates an open circular product in which the 5′-end of the transposon is separated from the donor sequence. Second strand nicking exposes the 3′-OH at the transposon end and linearizes the donor yielding the SEB product. A similar sequence of nicks at the other transposon end yields the DEB products, which are the plasmid backbone plus the excised transposon fragment (ETF). Excision is followed by insertion of the transposon in one of the various possible targets. Examples of inter- and intramolecular integration events are shown [for further details of these products see Chalmers and Kleckner (26)]. (B) The ‘in vitro hop’ assay for the quantification of intermolecular integration events. The transposon donor encodes a kanamycin resistance marker (KanR) flanked by Hsmar1 transposon ends. In vitro transposition is performed in presence of a target plasmid encoding a chloramphenicol resistance marker (CmR). The intermolecular transposition efficiency was obtained by transformation in E. coli and by dividing the number of colonies obtained after selection on Kan+Cm by the number of colonies obtained on Cm alone. No colonies were recovered if the donor, the target or the transposase were omitted. The donor plasmid has a conditional origin of replication that does not function in the recipient strain. This serves to eliminate any bias introduced by double transformation events in which a cell receives copies of both the donor and the target plasmid.

We applied two different strategies to detect the various intermediates and products of the reaction. In the first assay, transposition reactions were simply deproteinated and the products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The second type of assay used the ‘in vitro hop’ strategy. In this type of assay, a target plasmid is included in the transposition reaction mixture. Transposition events, from donor to target, are subsequently recovered by genetic transformation in E. coli (Figure 1B). The frequency of transposition is then obtained simply by counting the number of colonies obtained after selection of the appropriate antibiotic resistance markers (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). We confirmed that these colonies represented true transposition events by sequencing the junctions between the transposon and the target plasmid. All 51 sequenced insertions were precise and flanked by a duplicated target TA dinucleotide.

The effect of pH on excision and integration

Excision and intermolecular transposition were tested between pH 6 and 10 using the agarose gel electrophoresis and the in vitro hop assays, respectively (Figure 2A and B). The identities of the linear species, namely, the backbone, the excised transposon fragment (ETF) and the linear donor, were deduced from their positions in the gel relative to the molecular weight markers. However, the identities of the circular and topologically complex products were deduced from a 2D gel electrophoresis experiment described below.

Maximum excision, as judged by the amount of plasmid backbone released, was achieved between pH 8 and 9 but was detectable across the entire range tested (Figure 2A). Intermolecular transposition was less robust than excision: it was maximal at pH 8.5 but undetectable below pH 6.5 or above pH 9 (Figure 2B). Note that the high level of intermolecular transposition reported by the hop assay at pH 8.5 is not evident in the electrophoresis assay. This is because the substrate, which is the only target plasmid available in the electrophoresis assay, has been entirely consumed by the excision reaction (Figure 2A). Furthermore, in this assay, the persistence of un-integrated ETF at the extremes of pH indicates that integration is more severely affected by the pH than excision (Figure 2A, lanes 3 and 14, for example). Based on these results, we selected pH 8 as the standard condition used for all other experiments, unless stated otherwise. This pH is close to the physiological value (∼pH 7.2) and provides a high level of excision, while still supporting efficient integration.

The pH titration reveals several mechanistic insights into the cleavage reaction. Intermediates of the cleavage reaction accumulated at pH values outside the optimum range. For example, at pH 7.0 significant amounts of nicked and linear donor are present (Figure 2A, lane 5). The nicked donor represents transposons that have achieved cleavage of the first strand at one or both of the transposon ends, but not yet achieved second-strand cleavage at either end. The accumulation of this intermediate suggests that the transition between first- and second-strand cleavage is rate limiting during excision. It is possible that second-strand cleavage can only take place after a conformational change, and that this may be affected by the ionization of amino acid side chains. These effects will be considered in more detail below.

Identification of inter- and intramolecular integration products

At first sight cut-and-paste transposition reactions appear simple: a transposon is cut from the donor and inserted at a target site. However, detailed analysis of the Tn10 cut-and-paste transposition reaction using 2D gel electrophoresis revealed a large array of products (26). A number of factors contributing to the complexity of the reaction products were identified. These included trapped supercoil nodes in the intramolecular products, and the non-canonical synapsis of transposon ends: for example, pairs of ends located on different donor plasmids.

We performed a similar 2D analysis of the intermediates and products of the Hsmar1 reaction (Figure 3). Electrophoresis in the first dimension was performed at low agarose concentration, separating the products mainly according to their mass and, to a lesser extent, their topological structure. In the second dimension, higher agarose concentration, and the presence of ethidium bromide, decrease the electrophoretic mobility of nicked or gapped species compared with the linear products, separating the two types of molecules into two distinct arcs. The spectrum of Hsmar1 products appeared less complex than the equivalent analysis of Tn10 (26). However, all of the main classes of products expected from the canonical cut-and-paste transposition reaction were present.

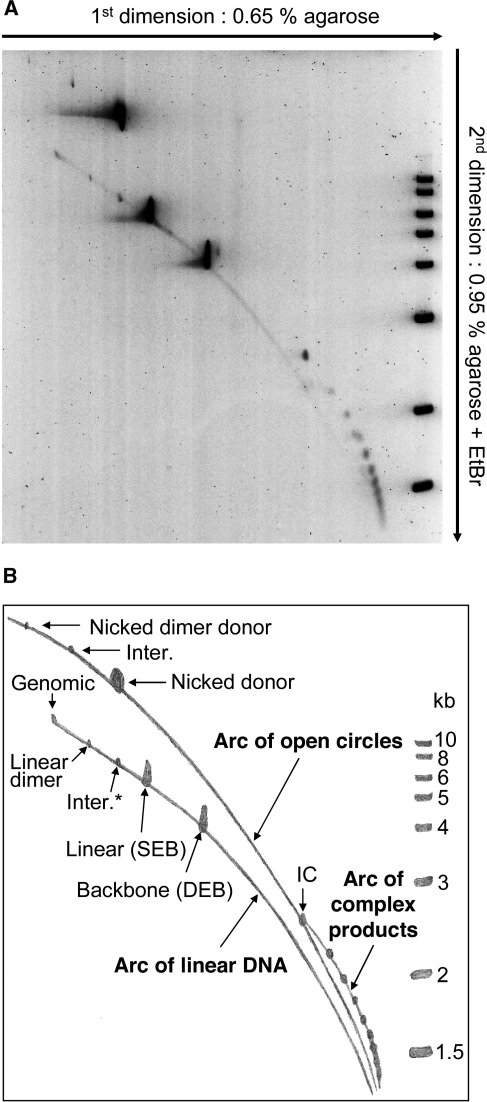

Figure 3.

Identification of transposition intermediates and products. (A) A transposition reaction was analyzed by 2D electrophoresis using the conditions indicated beside the gel. The reaction was performed at pH 7.5 for 12 h. The substrate (pRC1105) encodes a 2.3-kb transposon and a 4.2-kb backbone. The 2.3-kb transposon was constructed specifically to match the size of a Tn10 transposon that was previously used in a similar, but more extensive, 2D-gel analysis of transposition products (26). The previous analysis of Tn10 transposition products aided in the interpretation of the present gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with CYBR green and recorded on a fluorimager. The molecular weight ladder included on the second dimension is the same as that shown in Figure 2A. (B) A drawing of the gel in (A) indicating the identities of the different products detected. Most products were identified based on their size and position in the gel. A small quantity of nicked donor was present before the start of the reaction. The identities of the SEB and DEB products were confirmed by restriction digestion of material recovered from duplicate lanes of the first dimension. The identity of the canonical intermolecular insertion product into unreacted donor plasmids (Inter.) was confirmed by purifying it from the gel, followed by the restriction mapping and nucleotide sequencing of clones recovered following transformation in E. coli. The unknotted IC was identified by its position on the arc of open circles and by restriction digestion of material recovered from the gel (to be presented elsewhere). Despite the use of a recA− strain of E. coli, the substrate was contaminated with a small amount of dimeric plasmid. The positions of the nicked and linearized plasmid dimers are indicated.

The arc of open circles contained three main reaction products: (i) the nicked donor is present at the start of the reaction and is also produced by first-strand cleavage at one or both transposon ends; (ii) the canonical intermolecular product of transposition into unreacted donor plasmid (the identity of this product was confirmed by purifying it from the gel, followed by the analysis of clones recovered by transformation in E. coli, data not shown); (iii) the transposon inversion circle (IC), which is the product of intramolecular transposition events that trap no supercoiling nodes and therefore remain unknotted and uncatenated (Figure 1A).

The two main products on the arc of linear DNA were the SEB, which is identical in size to the linearized donor plasmid, and the donor backbone produced by excision of the transposon. No ETF was detected as it had all achieved integration. A minor product was detected at the size expected for a transposon insertion into a linear donor plasmid (Inter.*). This product is equivalent to the canonical ‘Inter.’ product on the arc of open circles, differing only in the topology of the target.

A third arc was also detected to the right of the arc of open circles. A similar arc in the Tn10 reaction was shown to contain the so-called ‘topologically complex products’. These products constitute a mixture of knotted and catenated transposon species that arise when intramolecular integration events trap supercoiling nodes between the transposon ends and the target site (26).

We estimate that under the standard reaction conditions, >90% of the excised transposon inserts into itself, rather than into another DNA molecule. This suicidal autointegration event is favored by the low DNA concentration in the reaction. Intramolecular target sites are favored because they are covalently linked to the transpososome and therefore have a high effective concentration. Auto-integration has also been reported for Mos1 (28,29).

Some transposons, such as phage Mu, have target immunity that affords protection from self-destructive autointegration events (30). In the case of phage Mu, target choice is dictated by the MuB accessory protein. The homomeric transposases of the cut-and-paste elements lack this sophistication and appear to be unable to distinguish inter- and intramolecular targets. Transposon circles are therefore abundant products in vitro. Intramolecular products are probably less abundant in vivo where the high DNA concentrations (∼10 mg/ml) in the bacterial cytoplasm and the eukaryotic nucleus provide for efficient intermolecular transposition. Nevertheless, transposon circles have been detected for several elements in vivo. Examples include Tn10, the Moloney retrovirus and the Ty1 retrotransposon (31–33). Presumably, mariner elements also produce transposon circles in vivo, although they have not yet been demonstrated to our knowledge.

Transposase concentration titration

Transposase concentration was titrated over a 1000-fold range using the electrophoresis and the in vitro hop assays (Figure 4). In the electrophoresis assay, where the substrate concentration was 6 nM, maximum excision was between 25 and 50 nM transposase (Figure 4A). At this point almost all of the supercoiled donor plasmid achieved excision. At even higher transposase concentration, the excision activity declined rapidly. Note that the intermolecular product disappears at 25–50 nM transposase because the substrate, which is the only target available in this assay, has been entirely consumed by the excision reaction. Of course, the in vitro hop assay is not subject to this limitation because the target plasmid does not encode transposon ends and is therefore not consumed.

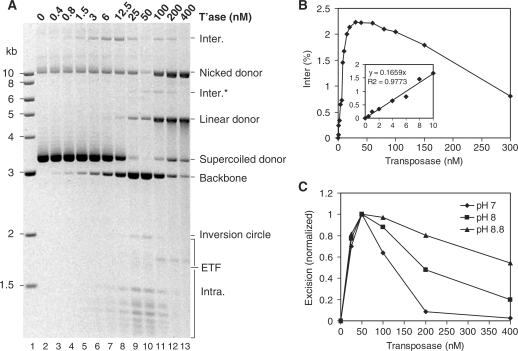

Figure 4.

Transposase titration of the transposition reaction. (A) The standard transposition reaction was titrated with the indicated amounts of transposase. The plasmid backbone is an end product of the reaction and is used to measure excision. The transposon donor plasmid (pRC650) was 6.4 nM. Maximum excision was at 25–50 nM transposase that equates to four to eight transposase molecules per transposition event. (B) The in vitro hop assay for intermolecular transposition was performed with the indicated amounts of transposase. The transposon donor plasmid (pRC704) and the target were each 1 nM. Maximum intermolecular transposition was at 25–50 nM transposase. Insert: early part of the curve with a line fitted to the points by the least square difference method. (C) Transposase titration of the transposition reaction was performed at the indicated pH values. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and recoded using a Kodak DC290 camera fitted with a 590DF100 Bandpass filter (BioRad). The transposon excision product (plasmid backbone) was quantified by analyzing the digital image using the Fuji ImageGauge software. The results for each titration were normalized to maximal activity at the respective pH values.

In the in vitro hop assay, where the substrate concentration was 1 nM, maximum transposition was at 30 nM transposase (Figure 4B). However, the linear region of the plot was between 0.5 and 10 nM transposase (Figure 4B, insert). The equation of the best fit straight line reveals that each additional transposition event requires the presence of a further six molecules of transposase (i.e. y = 0.166X or X = 6Y). However, since the purified transposase is unlikely to be 100% active, this is likely to be an over-estimate of the number of transposase monomers required per transposition event. Previous attempts to define the stoichiometry of the mariner transposition reaction by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) suggested four monomers per synaptic complex (i.e. two per single end), but it was unclear whether or not the observed complexes were the active species (25,34).

If the active multimer is indeed a tetramer, the linear increase in transposition at low protein concentration (Figure 4B) suggests that the transposase binding to the ITR is in dynamic equilibrium, at least up until the point at which an active multimer has been assembled and catalysis is initiated. If the transposase dimer instead bound tightly to the first ITR encountered, the excess of ITR present at low transposase concentrations would be expected to inhibit the reaction because of the high proportion of bound transposon ends that would not find a partner ITR on the same donor plasmid with which to interact.

The relative insensitivity of Hsmar1 transposition to the presence of competitor DNA, such as the target plasmid provided in the in vitro hop assay, reflects the low non-specific DNA binding activity of the transposase. The bacterial cut-and-paste transposases, such as Tn10, have a strong non-specific DNA binding activity and are severely inhibited by competitor DNA. These enzymes seem to have a limited ability to diffuse away from the site of synthesis, which, in bacteria, is physically linked to the encoding element by the coupling of transcription and translation. They, therefore, act in cis to the encoding element and tend to synapse the first two transposon ends that they encounter (26). Of course, transcription and translation are separate in eukaryotes and this probably mandates that their transposases, such as mariner, act freely in trans to the encoding elements.

The free diffusion of mariner family transposases has a number of biological consequences. It explains the amplification of inactive elements and deletion derivatives (MITES). This in large part accounts for the lifestyle of the mariner family elements, where the invasion of a genome by horizontal transfer is followed by vertical inactivation leading to the eventual extinction of activity (2,3).

OPI

Hartl and colleagues (35) proposed that the Mos1 mariner element was regulated by a mechanism termed ‘OPI’. They observed that excision of a non-autonomous element ‘peach’ was reduced in flies overproducing the Mos1 transposase (35). They suggested that this was an adaptive mechanism that protected the host from excessive transposition: OPI was postulated to reduce the rate of transposition as the number of active elements increased during the amplification phase following invasion of the genome. Inhibition of transposition at high transposase concentrations has been documented for other mariner elements and bacterial transposons, and probably reflects a concentration-dependent aggregation of transposases (4,35–37).

OPI also affects the Hsmar1 reaction (Figure 4A and B). Transposition was inhibited by 50% at a transposase concentration only about 4-fold above the optimum. However, OPI also depends on the pH of the reaction and the effect was more pronounced at pH 7 and less pronounced at pH 8.8 (Figure 4C).

In the electrophoretic and in vitro hop assays, inhibition starts at the same transposase concentration (25–50 nM). However, there is more than a 6-fold difference in donor DNA concentration in these assays. OPI is therefore not due to a competition for ITR binding, or saturation with transposases, rather, it depends on the absolute transposase concentration, and may therefore arise from a simple aggregation mechanism. The finding that OPI is reduced at higher pH might therefore reflect a reduction in the strength of protein–protein interactions.

Kinetic analysis of transposition

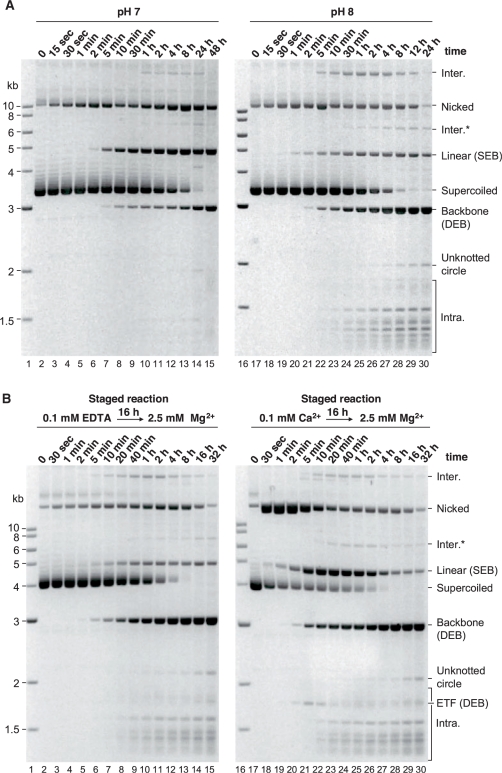

Kinetic analysis of the transposition reaction was performed at pH 7 and 8 (Figure 5A). Although excision products were detected several minutes after the start of the reaction, 12 h was required for completion at pH 8, while at pH 7 the reaction was not complete even after 48 h. In both conditions, the appearance of the backbone was not matched by the appearance of the 1.7-kb ETF at the expected position in the gel. Instead, inter- and intramolecular integration products were detected. This suggests that integration of the ETF into a target site is faster than the excision reaction which is therefore rate limiting for transposition as a whole.

Figure 5.

Kinetic analysis of the transposition reaction. (A) Kinetic analysis of the standard transposition reaction was performed at pH 7 and 8. Aliquots were withdrawn at the indicated time points, the reaction terminated and the products of the reaction were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (see ‘Material and Methods’ section). (B) The transposase and the donor plasmid were preincubated for 16 h in the presence of 0.1 mM EDTA or 0.1 mM Ca2+ as indicated. Mg2+ was added at time 0. Reactions were analyzed as described in (A). Note that the same substrate is used in (A) and (B): compare the positions of the linear plasmids and the backbones relative to the molecular weight markers. The relative position of the supercoiled plasmid is different in (A) and (B), because the migration of circular DNA molecules is extremely sensitive to the electrophoresis conditions: for example, the voltage applied or the depth of the buffer above the gel can change its mobility relative to linear DNA markers.

The intermediate steps of the reaction appear to be slower at pH 7 than at pH 8. The different steps are also affected to different degrees. For example, the supercoiled donor is all reacted after 24 h at either of the pH value, but only ∼30% is converted to backbone at pH 7 (Figure 5A, lane 14). At pH 7, a significant fraction of the donor is trapped at the SEB stage of the reaction represented by the linearized donor plasmid.

The mariner transposases do not require divalent metal ions for specific protein–ITR binding, and single-end complexes (SECs) are readily detected by EMSA (8,25,34). Paired-ends complexes (PECs) have been more difficult to detect by EMSA. The Mos1 PEC can be detected after pre-incubation with 0.1 mM Mg2+ (13). However, this also supports a low level of cleavage, which is inconvenient for many experimental purposes. In some systems, Ca2+ can substitute for Mg2+ during PEC assembly, even though it does not support cleavage of the transposon ends. This was first demonstrated for the phage Mu transpososome, and subsequently for the Hsmar1 domain of the human SETMAR protein (8,38).

To investigate whether assembly of the protein–DNA complexes is rate limiting for excision, staged reactions were performed in which transposase was preincubated with the donor plasmid, either in the presence or in the absence of Ca2+, before addition of the catalytic metal ion at time 0 (Figure 5B).

Preincubation of the transposase with the donor DNA for 16 h in the absence of metal had no effect on the kinetics of the reaction (compare left panel of Figure 5B with right panel of Figure 5A). However, when the assay was preincubated in the presence of Ca2+, the reaction, as measured by the disappearance of the supercoiled substrate, was greatly accelerated (Figure 5B, compare left and right panels). After Ca2+ preincubation, ∼75% of the supercoiled donor was converted to the nicked intermediate in the first 30 s. Without Ca2+ preincubation, a similar level was achieved only after 2 h (Figure 5B, compare lanes 11 and 18). The first chemical step of the reaction is therefore accelerated by more than 100-fold in the staged reaction. The reaction was not accelerated when transposase was preincubated with Ca2+ and non-specific DNA prior to the addition of the substrate (data not shown). This excludes the Ca2+-dependent assembly of a transposase–transposase complex as the factor responsible for accelerating the reaction.

Preincubation with Ca2+ served to synchronize the reaction, and helps to reveal the kinetic relationship between the intermediates (Figure 5B, right panel). The nicked intermediate peaked after only 1 min and then declined as it was converted to the SEB intermediate. Likewise, the amount of SEB intermediate increased rapidly, peaked after 20 min and then declined as it was converted to the double-end break (DEB) products (i.e. backbone plus ETF). Synchronization of the reaction also revealed the ETF intermediate, which is not usually detected under the optimal reaction conditions because it is rapidly converted to integration products. The ETF is most clearly seen at the 5-min time point (Figure 5B, lane 21). However, note that the diffuse band that appears at approximately the same position in the gel at late time points is one of the topologically complex intramolecular integration products identified in Figure 3. Finally, the backbone, which is an end product of the reaction, accumulated throughout the experiment. In summary, the Hsmar1 cleavage reaction appears to progress in the canonical fashion as illustrated in Figure 1A: the supercoiled donor is sequentially converted to the nicked, SEB and DEB intermediates.

Does first-strand nicking require PEC assembly?

Synchronization of the reaction by Ca2+ preincubation allows the rate-limiting steps of the reaction to be discerned. For example, the rapid consumption of supercoiled donor in the staged reaction suggests that first-strand nicking is preceded by a slow step, and that this requires a divalent metal ion. We would like to propose that this slow step corresponds to the assembly of the PEC. However, it has been suggested previously that first-strand nicking and/or the SEB in mariner transposition might be independent of synapsis (13,25,39). This is a controversial suggestion because it challenges the paradigm established for other well-characterized members of the DDE family of transposases, where synapsis is a prerequisite for catalysis [(25) and references therein]. However, the evidence for catalysis in the absence of synapsis is not conclusive. For Mos1, the evidence was based on the inability to detect the PEC except under catalytic conditions, and on the SEB phenotype of a transposase point mutation that was thought to weaken subunit interactions (13,39). The evidence for Himar1 was based on the in-gel cleavage of SECs purified by EMSA (25). The caveat in this case was that the extended incubation time provided an opportunity for de novo PEC assembly in the gel.

The reaction kinetics presented here strongly suggest that the rate of first-strand nicking is limited by the Ca2+-dependent assembly of a complex. In principle, this could be any protein–protein or protein–DNA complex. However, nicking was not accelerated when transposase was preincubated with Ca2+ and non-specific DNA prior to the addition of the substrate. This excludes the Ca2+-dependent assembly of a protein–protein complex as the factor responsible for accelerating the rate. We therefore conclude that the rate of first-strand nicking is limited by the assembly of a complex between transposase and the transposon end(s). Whether or not this corresponds to a PEC awaits definitive proof.

Idenification of other rate-limiting steps

The reaction kinetics (Figure 5) allow additional rate-limiting steps to be identified as follows: preincubation (with or without Ca2+) did not alter the rate at which the backbone appeared. The rate of excision is, therefore, limited mainly by one of the catalytic steps, rather than by protein–ITR binding or synapsis. Since first-strand nicking is rapid, the overall rate of the reaction must be limited by the production of the SEB or the DEB, which corresponds to nicking of the second strand at one or both transposon ends, respectively. This is supported by the accumulation of the SEB intermediate in staged and unstaged reactions. This shows that cleavage of the second strand at the second transposon end is rate limiting for the overall rate of transposition (i.e. integration).

If the assembly of a catalytically active complex was much faster than second-strand cleavage, the nicked intermediate would accumulate in the unstaged reaction. Assembly of the active complex and second-stand cleavage (at one end or the other) are therefore both rate-limiting steps. Moreover, the rates of the slow steps (complex assembly, SEB and DEB) must be similar to each other since the nicked and linear intermediates reach steady-state levels in unstaged reactions, instead of appearing and disappearing during the course of the reaction. Taking the kinetic evidence as a whole, the relative rates of the different steps can be summarized as follows:

assembly* << first nick >> second nick (SEB) ≥ DEB << integration, where assembly* indicates the divalent metal ion-dependent assembly of a complex between transposase and the transposon end(s).

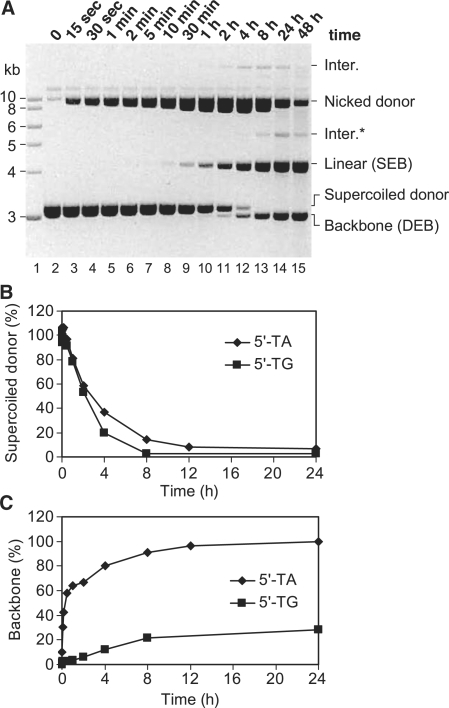

The importance of the flanking TA dinucleotide

All members of the mariner family of transposons have a strong preference for a TA dinucleotide at the target site. The target dinucleotide is duplicated during integration and the transposons are consequently flanked by symmetrical 5′-TA dinucleotides on either side. To investigate the potential role of this motif in the transposition reaction, we constructed a transposon flanked by symmetrical 5′-TG dinucleotides on either side. Kinetic analysis revealed that the first catalytic step (nicking of the first strand at one of the two transposon ends) was normal as judged by the disappearance of the supercoiled donor (Figure 6A and B). However, second-strand cleavage is significantly delayed and the nicked intermediate accumulates. Much of this eventually achieves second-strand cleavage and is converted to the SEB intermediate (Figure 6A). The SEB itself persists much longer than normal before it is converted to backbone (Figure 6A and C). As pointed out above, this delay corresponds to slow cleavage of the second strand at the second transposon end. Finally, the flanking dinucleotide did not affect the integration step of the reaction: no ETF was detected in this experiment as it was rapidly converted to integration products (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of the flanking TA dinucleotide on transposon excision. (A) Kinetic analysis of a transposition reaction was performed as described for Figure 5 using a donor plasmid (pRC824) in which the flanking 5′-TA dinucleotide at each end of the transposon was replaced by 5′-TG. (B and C) The effect of the 5′-dinucleotide on the rate of first-strand cleavage and excision. The gel in (A) of this figure and the gel shown in the right panel of Figure 5A were quantified as described in Figure 4.

The kinetic analysis presented in the previous section demonstrated that second-strand cleavage is the rate-limiting step of the reaction. We postulated that this corresponds to a significant conformational change in the transpososome between first- and second-strand cleavage. The further reduction in the rate of second-strand cleavage caused by mutation of the flanking TA dinucleotides suggests that the transposase makes critical contacts with these bases during this transition.

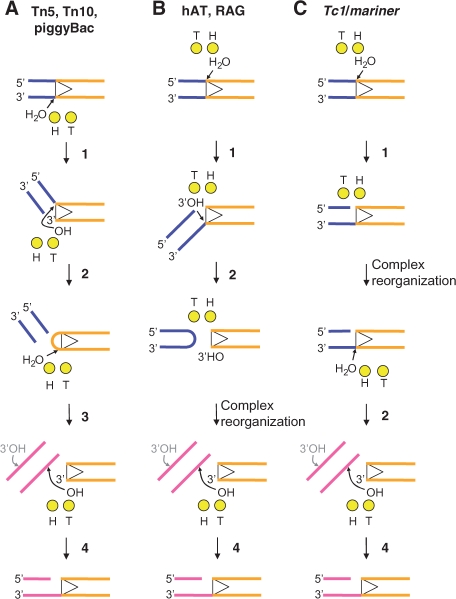

Two metal ion catalysis in mariner transposition

The mechanism of second-strand cleavage in mariner transposons is one of the most significant gaps in our knowledge of the DNA transposons. Nearly all DDE family cut-and-paste transposons studied to date use the DNA-hairpin mechanism (17,18,40,41). This allows one subunit of the homomultimeric transposase to perform double-strand cleavage at one transposon end. Tn7 is a notable exception. It uses different subunits of a heteromeric transposase to cleave the two strands of DNA (42). The mariner family of transposons is therefore unusual because it has a homomeric transposase, but lacks the expected DNA hairpin intermediate (13,20).

Yang and colleagues (21) have proposed a ping-pong mechanism in which the chemical steps of the transposition reaction are achieved by the selective use of ‘hydrolysis’ (H) and ‘transfer’ (T) metal ions coordinated by the DDE(D) triad of active site amino acids (21). According to this model, a transposase that cleaves the transferred strand first would use the metal ions in the order H-T-H-T (Figure 7A). Alternation of the metal ion action would limit the extent of the conformational changes required, because the product of one reaction is used as a substrate in the following reaction. In many eukaryotic systems, which cleave the non-transferred strand first, the order is proposed to be H-T-T. Repetition of the T-reaction presumably involves a significant structural transition as the active site moves from one 3′-OH to the other (Figure 7B). The lack of a hairpin intermediate in mariner transposition suggests that it may represent a ‘third way’ in which the order of the reaction is H-H-T. If this is the case, then we might expect to detect a significant structural transition between first- and second-strand cleavage, as the active site moves from one strand to the other (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

A ‘ping-pong’ model for two metal ion catalysis in the DDE(D) family of transposases. In this model, the catalytic metal ions are designated as the ‘hydrolysis’ (H) and ‘transfer’ (T) metal ions according to their respective functions (see text for details). Figure is based on the model by Nowotny and colleagues (21). The chemical steps of the reaction are numbered as follows: 1, first-strand nicking; 2, second-strand nicking; 3, hairpin resolution; and 4, strand transfer (integration). The elements of the picture are color coded: transposon end, dark yellow; catalytic metal ions, light yellow spheres; flanking DNA, blue; target DNA, magenta. hAT stands for the hobo-Ac-Tam3 family of transposons; RAG is the V(D)J recombinase RAG1/2 which is a distant member of the DDE superfamily. (A) Tn5, Tn10 and piggyback initiate catalysis by hydrolyzing the terminal phosphodiester bond on the transferred strand. The resulting 3′-OH is used as a nucleophile to attack the opposite DNA strand. This generates a double-strand break on the flanking DNA and a hairpin on the transposon end. The hairpin is resolved by a second hydrolysis reaction, regenerating the terminal 3′-OH which then attacks a phosphodiester bond at the target site. The H and T metal ions are used alternately in the order H-T-H-T. (B) The polarity of the hairpin reaction is reversed in the eukaryotic hAT transposons and the RAG1/2 recombinase reaction. The non-transferred strand is cleaved first by a transposase-mediated hydrolysis reaction. The resulting 3′-OH flanking the transposon is then used as a nucleophile to attack the opposite strand, producing a hairpin on the flanking DNA. This transesterification reaction liberates the 3′-OH on the transposon end which is used for the integration step. Here the catalytic ions are used in the order H-T-T. This presumably requires reorganization of the complex as the T metal ion moves between the 3′-OH on the flanking DNA and the 3′-OH on the transposon end. (C) Members of the Tc1/mariner superfamily lack the hairpin intermediate. As for hAT elements, the first nick is on the non-transferred strand. However, second-strand nicking likely involves a second hydrolysis step instead of a hairpin. In consequence, the use of the metal ions would follow the order H-H-T, suggesting the need for a structural reorganization of the transpososome between the first- and second-strand cleavage.

In this study, we have shown that the second-strand cleavage step is rate limiting for mariner transposition (Figure 5B). This correlates with the structural transition proposed to take place between first- and the second-strand cleavage. Moreover, the flanking TA dinucleotides appear to be required for this conformational change (Figure 6).

Our current data do not exclude second-strand cleavage by a different transposase monomer. In this case, the rate limitation reflects the movement of one monomer out of the way to let the other in. This, of course, would be unparsimonious because it would require identical monomers to perform different tasks. It would, however, agree with a reaction stoichiometry requiring four monomers per transposition event.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Wellcome Trust (to R.C.); BBSRC Doctoral Training Program (to C.C.B.). Funding for open access charge: The Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Neil Walker for technical help and other members of the lab for helpful discussions throughout the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robertson HM. The mariner transposable element is widespread in insects. Nature. 1993;362:241–245. doi: 10.1038/362241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson HM, Lampe DJ. Recent horizontal transfer of a mariner transposable element among and between Diptera and Neuroptera. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1995;12:850–862. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohe AR, Moriyama EN, Lidholm DA, Hartl DL. Horizontal transmission, vertical inactivation, and stochastic loss of mariner-like transposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1995;12:62–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartl DL, Lozovskaya ER, Nurminsky DI, Lohe AR. What restricts the activity of mariner-like transposable elements. Trends Genet. 1997;13:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson HM, Zumpano KL. Molecular evolution of an ancient mariner transposon, Hsmar1, in the human genome. Gene. 1997;205:203–217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordaux R, Udit S, Batzer MA, Feschotte C. Birth of a chimeric primate gene by capture of the transposase gene from a mobile element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8101–8106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pace JK, 2nd, Feschotte C. The evolutionary history of human DNA transposons: evidence for intense activity in the primate lineage. Genome Res. 2007;17:422–432. doi: 10.1101/gr.5826307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D, Bischerour J, Siddique A, Buisine N, Bigot Y, Chalmers R. The human SETMAR protein preserves most of the activities of the ancestral Hsmar1 transposase. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:1125–1132. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01899-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson EA, Rasila KK, Corwin LK, Wray J, Beck BD, Severns V, Mobarak C, Lee SH, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. The SET and transposase domain protein Metnase enhances chromosome decatenation: regulation by automethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5822–5831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wray J, Williamson EA, Royce M, Shaheen M, Beck BD, Lee SH, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. Metnase mediates resistance to topoisomerase II inhibitors in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miskey C, Papp B, Mates L, Sinzelle L, Keller H, Izsvak Z, Ivics Z. The ancient mariner sails again: transposition of the human Hsmar1 element by a reconstructed transposase and activities of the SETMAR protein on transposon ends. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:4589–4600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claeys Bouuaert C, Chalmers R. Gene therapy vectors: the prospects and potentials of the cut-and-paste transposons. Genetica. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10709-009-9391-x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson A, Finnegan DJ. Excision of the Drosophila mariner transposon mos1. Comparison with bacterial transposition and v(d)j recombination. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bischerour J, Chalmers R. Base-flipping dynamics in a DNA hairpin processing reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2584–2595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bischerour J, Chalmers R. Base flipping in Tn10 transposition: an active flip and capture mechanism. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bischerour J, Lu C, Roth DB, Chalmers R. Base flipping in V(D)J recombination: insights into the mechanism of hairpin formation and the 12/23 rule. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:5889–5899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00187-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitra R, Fain-Thornton J, Craig NL. piggyBac can bypass DNA synthesis during cut and paste transposition. EMBO J. 2008;27:1097–1109. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou L, Mitra R, Atkinson PW, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Craig NL. Transposition of hAT elements links transposable elements and V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2004;432:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature03157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickman AB, Li Y, Mathew SV, May EW, Craig NL, Dyda F. Unexpected structural diversity in DNA recombination: the restriction endonuclease connection. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson JM, Dawson A, O’Hagan N, Taylor P, Finnegan DJ, Walkinshaw MD. Mechanism of Mos1 transposition: insights from structural analysis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1324–1334. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasnauskas G, Halford SE, Siksnys V. How the BfiI restriction enzyme uses one active site to cut two DNA strands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6410–6415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampe DJ, Churchill ME, Robertson HM. A purified mariner transposase is sufficient to mediate transposition in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:5470–5479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz-Lopez M, Siddique A, Bischerour J, Lorite P, Chalmers R, Palomeque T. Transposition of Mboumar-9: identification of a new naturally active mariner-family transposon. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipkow K, Buisine N, Lampe DJ, Chalmers R. Early intermediates of mariner transposition: catalysis without synapsis of the transposon ends suggests a novel architecture of the synaptic complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:8301–8311. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8301-8311.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalmers RM, Kleckner N. IS10/Tn10 transposition efficiently accommodates diverse transposon end configurations. EMBO J. 1996;15:5112–5122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auge-Gouillou C, Brillet B, Germon S, Hamelin MH, Bigot Y. Mariner Mos1 transposase dimerizes prior to ITR binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brillet B, Bigot Y, Auge-Gouillou C. Assembly of the Tc1 and mariner transposition initiation complexes depends on the origins of their transposase DNA binding domains. Genetica. 2007;130:105–120. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-0025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinzelle L, Jegot G, Brillet B, Rouleux-Bonnin F, Bigot Y, Auge-Gouillou C. Factors acting on Mos1 transposition efficiency. BMC Mol. Biol. 2008;9:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell A, Craigie R, Mizuuchi K. B protein of bacteriophage mu is an ATPase that preferentially stimulates intermolecular DNA strand transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:699–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garfinkel DJ, Stefanisko KM, Nyswaner KM, Moore SP, Oh J, Hughes SH. Retrotransposon suicide: formation of Ty1 circles and autointegration via a central DNA flap. J. Virol. 2006;80:11920–11934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01483-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamin HW, Kleckner N. Intramolecular transposition by Tn10. Cell. 1989;59:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoemaker C, Hoffman J, Goff SP, Baltimore D. Intramolecular integration within Moloney murine leukemia virus DNA. J. Virol. 1981;40:164–172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.40.1.164-172.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auge-Gouillou C, Brillet B, Hamelin MH, Bigot Y. Assembly of the mariner Mos1 synaptic complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:2861–2870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2861-2870.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohe AR, Hartl DL. Autoregulation of mariner transposase activity by overproduction and dominant-negative complementation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:549–555. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chalmers RM, Kleckner N. Tn10/IS10 transposase purification, activation, and in vitro reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:8029–8035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lampe DJ, Grant TE, Robertson HM. Factors affecting transposition of the Himar1 mariner transposon in vitro. Genetics. 1998;149:179–187. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuuchi M, Baker TA, Mizuuchi K. Assembly of the active form of the transposase-Mu DNA complex: a critical control point in Mu transposition. Cell. 1992;70:303–311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90104-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Dawson A, Finnegan DJ. DNA-binding activity and subunit interaction of the mariner transposase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3566–3575. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennedy AK, Guhathakurta A, Kleckner N, Haniford DB. Tn10 transposition via a DNA hairpin intermediate. Cell. 1998;95:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhasin A, Goryshin IY, Reznikoff WS. Hairpin formation in Tn5 transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37021–37029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarnovsky RJ, May EW, Craig NL. The Tn7 transposase is a heteromeric complex in which DNA breakage and joining activities are distributed between different gene products. EMBO J. 1996;15:6348–6361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.