Abstract

Background

Almost 1 million Americans are infected with HIV, yet it is estimated that as many as 250,000 of them do not know their serostatus. This study examined whether people residing in states with statutes requiring written informed consent prior to HIV testing were less likely to report a recent HIV test.

Methods

The study is based on survey data from the 2004 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between residence in a state with a pre-test written informed-consent requirement and individual self-report of recent HIV testing. The regression analyses controlled for potential state- and individual-level confounders.

Results

Almost 17% of respondents reported that they had been tested for HIV in the prior 12 months. Ten states had statutes requiring written informed consent prior to routine HIV testing; nine of those were analyzed in this study. After adjusting for other state- and individual-level factors, people who resided in these nine states were less likely to report a recent history of HIV testing (OR=0.85; 95% CI=0.80, 0.90). The average marginal effect was −0.02 (p<0.001, 95%CI= −0.03, −0.01); thus, written informed-consent statutes are associated with a 12% reduction in HIV testing from the baseline testing level of 17%. The association between a consent requirement and lack of testing was greatest among respondents who denied HIV risk factors, were non-Hispanic whites, or who had higher levels of education.

Conclusions

This study’s findings suggest that the removal of written informed-consent requirements might promote the non–risk-based routine-testing approach that the CDC advocates in its new testing guidelines.

Background

Almost 1 million Americans are infected with HIV, yet it is estimated that as many as 250,000 of them do not know their serostatus.1 Unless rates of HIV testing increase, many of the undiagnosed will not learn of their infection and will remain infectious until the onset of AIDS. Currently, almost 40% of HIV diagnoses nationwide are made within 1 year of an AIDS diagnosis.2 Such “late-testers” are unaware of their HIV status for as long as 1 decade after infection. Once diagnosed, HIV-infected individuals reduce their risk behaviors by about half.3 Thus, some late-testers are believed to contribute substantially to ongoing community HIV transmission.3,4 The undiagnosed are also deprived of the multiple health benefits of antiretroviral therapy.4

In response to the persistent problem of late HIV diagnosis and increasing numbers of new diagnoses among people who might not consider themselves at risk—such as heterosexual men and women as well as people aged <25 years or >50 years—public health authorities have recently pushed to lower the barriers to HIV diagnosis for all Americans.5,6 The 2006 guidelines for HIV testing from the CDC explicitly seek “to increase diagnosis of HIV infection, destigmatize the testing process” and promote “adoption of routine HIV testing in all healthcare settings” among people aged 13–64 years.7 To move toward this goal, the guidelines state that “a separate written consent for HIV testing should not be required” and that “general consent for medical care should be considered sufficient to encompass consent for HIV testing.” A similar approach has successfully increased prenatal HIV testing, but few studies have considered the potentially negative effect that written informed-consent requirements could have on HIV testing rates in the general population.8,9

Laws that require healthcare providers to obtain written informed consent prior to HIV testing originated in the late 1980s, when HIV was both untreatable and greatly stigmatized.10 At that time, AIDS activists lobbied for legal mandates that would prevent people from being tested without their knowledge. Legislators responded by crafting laws to protect the autonomy and confidentiality of people potentially infected with the disease. These statutes may have initially encouraged testing uptake among people at risk.11

However, the statutes have remained in force even as HIV has become a treatable chronic disease.12 By requiring extra explanatory time and a specific signed consent, these statutes set HIV apart from other chronic diseases for which people commonly undergo routine blood screening (e.g., hepatitis C, prostate cancer, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia). With this potential barrier in place, a time-pressed provider may be inclined to defer testing for patients who do not appear likely to participate in traditionally recognized HIV risk activities such as IV drug use, anal sex without a condom, exchanging money or drugs for sex, or recent treatment for a sexually transmitted disease.13–17 Such an outcome contradicts the intention of the new CDC guidelines on routine HIV testing.

To assess the effect of written informed-consent statutes, this study examined the natural experiment created by the variation of HIV-related statutes among U.S. states. Data from the 2004 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were used to compare the likelihood of self-reporting an HIV test in the prior 12 months among those who lived in states that required written informed consent to the likelihood of self-reporting among those who did not live in states with a requirement for written informed consent.

Methods

Individual-level data from the 2004 BRFSS were linked with data from the individuals’ states of residence, including the presence of state HIV-testing statutes. The study sample included all 2004 BRFSS respondents aged 18–64 years who lived in the U.S. (excluding Hawaii, Washington DC, and U.S. territories). The lower end of the age range was chosen because the BRFSS did not interview people aged <18 years. The upper end was chosen because the CDC is specifically seeking to increase testing among adults aged <65 years. Hawaii was excluded from the analysis because it did not participate in the 2004 BRFSS. Washington DC was excluded because data were not available on federal funding for HIV prevention.

Data Sources

Individual-level CDC BRFSS data were augmented with additional state-level variables from three sources: public records of state statutes, CDC HIV/AIDS surveillance reports, and the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) funding-level reports. The most recent year for which information was available from all three sources of data was 2004.

The CDC’s BRFSS

Each year since 1994, the BRFSS has surveyed by telephone the U.S. population about behavioral risk factors that might influence morbidity and mortality among adults.18 The 2004 survey had a median response rate of 52.7%. Respondents were asked to provide sociodemographic information (e.g., age, gender, income); educational attainment; and healthcare-insurance coverage, including type of plan (e.g., prepaid plans such as HMOs or government plans such as Medicare). For race/ethnicity, respondents were asked if they defined themselves as white, black, or African American; Asian, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander; American Indian; Alaska Native; or other. In a separate question, they were asked if they were Hispanic or Latino.

Respondents were also asked about their HIV risk behaviors (i.e., whether within the last year they had used intravenous drugs, whether they had been treated for a sexually transmitted disease or venereal disease, whether they had given or received money or drugs in exchange for sex, or whether they had had anal sex without a condom) and prior experience with HIV testing. If respondents had ever been tested for HIV, then they were asked the number of times that they had been tested for HIV within the past year.

Statutes requiring written consent in 2004

Compilations of all state HIV-related statutes were published in 1995, 1998, and 2004 by the journal Law & Sexuality.19–21 For this study, two independent reviewers (an attorney and a physician) cross-referenced those compilations with ones stored in the Westlaw database (www.westlaw.com), an online legal-research tool, to identify relevant statutes for review. Search terms included HTLV, HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, in conjunction with the term test! as well as the terms consent, consult!, writ!, and oral.

States were categorized according to whether or not they had a statute requiring specific written informed consent prior to HIV testing during routine, non-emergent medical care. Statutes were categorized as no written consent needed if there were numerous exceptions to the locations in which the requirement was in force; if allowance for a general written consent to medical services was made; or if the statute focused the requirement on special situations such as emergent medical conditions; occupational exposures; insurance requirements; sexual or other criminal offenses; blood, organ, or tissue donation; pregnancy; or de-identified medical research. Discordant categorizations of statutes (n=3/50) between the reviewers were resolved via discussion.

Surveillance reports from the CDC on HIV/AIDS

Publicly available CDC data on AIDS prevalence per capita for 2004 were used as a continuous variable to control for the potential association between AIDS prevalence and self-reported testing rates.22

Data from NASTAD on CDC HIV-prevention funds

NASTAD documents the annual HIV-prevention funding provided by the CDC to state and local departments of health. A previously published methodology to create quintiles of funding levels across 1998–2003 was used under the assumption that previous years of funding would influence future outcomes.23 Quintiles of CDC funding control for the potential association between prevention spending and self-reported testing rates.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in 2006–2008 using Stata, version 10.1, taking into account the complex survey design of the BRFSS. The primary outcome of interest was whether respondents reported that they had been tested for HIV in the prior 12 months. The primary exposure of interest was residence in a state with a statute requiring written informed consent. Potential confounders at the individual and state levels (Table 1) were selected, based on similar studies.11,23 The state-level confounders included NASTAD funding and statewide AIDS prevalence.

Table 1.

Factors associated with the odds of an individual’s reporting an HIV test within the last 12 months

| Independent variables | Complete survey cohort (weighted) |

Unadjusted analyses |

Adjusted analyses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR |

p- value |

CI (min) |

CI (max) |

OR |

p- value |

CI (min) |

CI (max) |

||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 48.4% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Female | 51.6% | 1.07 | 0.005 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 0.021 | 1.01 | 1.12 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 13.1% | ref | ref | ||||||

| 25–34 | 18.3% | 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.910 | 0.93 | 1.09 |

| 35–44 | 20.4% | 0.46 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| 45–54 | 18.8% | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| 55–64 | 12.9% | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 69.6% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Black | 9.8% | 4.07 | <0.001 | 3.83 | 4.32 | 3.40 | <0.001 | 3.18 | 3.63 |

| Hispanic | 14.7% | 1.90 | <0.001 | 1.75 | 2.07 | 1.63 | <0.001 | 1.48 | 1.79 |

| Multiracial | 1.4% | 1.69 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 2.00 | 1.57 | <0.001 | 1.32 | 1.85 |

| Asian/PI/AI | 4.5% | 1.58 | <0.001 | 1.40 | 1.79 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 1.64 |

| Education level | |||||||||

| Did not graduate high school | 11.0% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Graduated high school | 30.6% | 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| Attended college/technical school | 26.5% | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.92 |

| Graduated college/technical school | 31.9% | 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.84 |

| Incomea ($) | |||||||||

| <15,000 | 12.0% | ref | ref | ||||||

| 15,000–<25,000 | 17.8% | 0.95 | 0.358 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 0.810 | 0.92 | 1.12 |

| 25,000–<35,000 | 13.3% | 0.78 | <0.001 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.013 | 0.79 | 0.97 |

| 35,000–<50,000 | 16.4% | 0.60 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.88 |

| ≥50,000 | 40.5% | 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.82 |

| Insurance status | |||||||||

| Insured | 83.7% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Un-insured | 15.9% | 1.25 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.34 | 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||

| Married/committed relationship | 57.5% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Single | 42.5% | 1.92 | <0.001 | 1.83 | 2.02 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 1.37 |

| Language of choiceb | |||||||||

| English | 98.0% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Non-English | 2.0% | 1.13 | 0.074 | 0.99 | 1.29 | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 0.80 |

| Traditional HIV risk factors | |||||||||

| Absent | 96.9% | ref | ref | ||||||

| Present | 3.1% | 2.90 | <0.001 | 2.60 | 3.23 | 1.93 | <0.001 | 1.72 | 2.16 |

| Prevalence of AIDS per capita (state) | n/a | 7.09 | <0.001 | 5.51 | 9.13 | 4.88 | <0.001 | 3.29 | 7.25 |

| Federal prevention funding (state) | n/a | 1.10 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 0.022 | 1.00 | 1.05 |

|

Living in a state that requires written consent prior to HIV testing |

n/a | 0.96 | 0.081 | 0.91 | 1.10 | 0.85 | 0.000 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

>10% of respondents did not report income data. They are not presented here, but were included in adjusted analyses.

The adjusted calculation is not controlled by race/ethnicity.

AI, American Indian; max, maximum; min, minimum; PI, Pacific Islander

Statistical analysis occurred in three steps. First, unadjusted analyses (Table 1) were performed by calculating the odds of self-reported HIV testing, stratified by the potentially confounding variables. Bivariate tests were used to compare potential individual- and state-level confounders between individuals who had and had not undergone testing. Second, adjusted analyses were conducted with multivariate logistic regression. To build the final model, each potential confounder was added sequentially, and changes were evaluated in the estimated effect of living in a state with a statute requiring written consent on the probability of testing. Variables in the final model were retained if there was evidence of significant confounding (change in OR of ≥15%) or if they were identified a priori as important covariates.

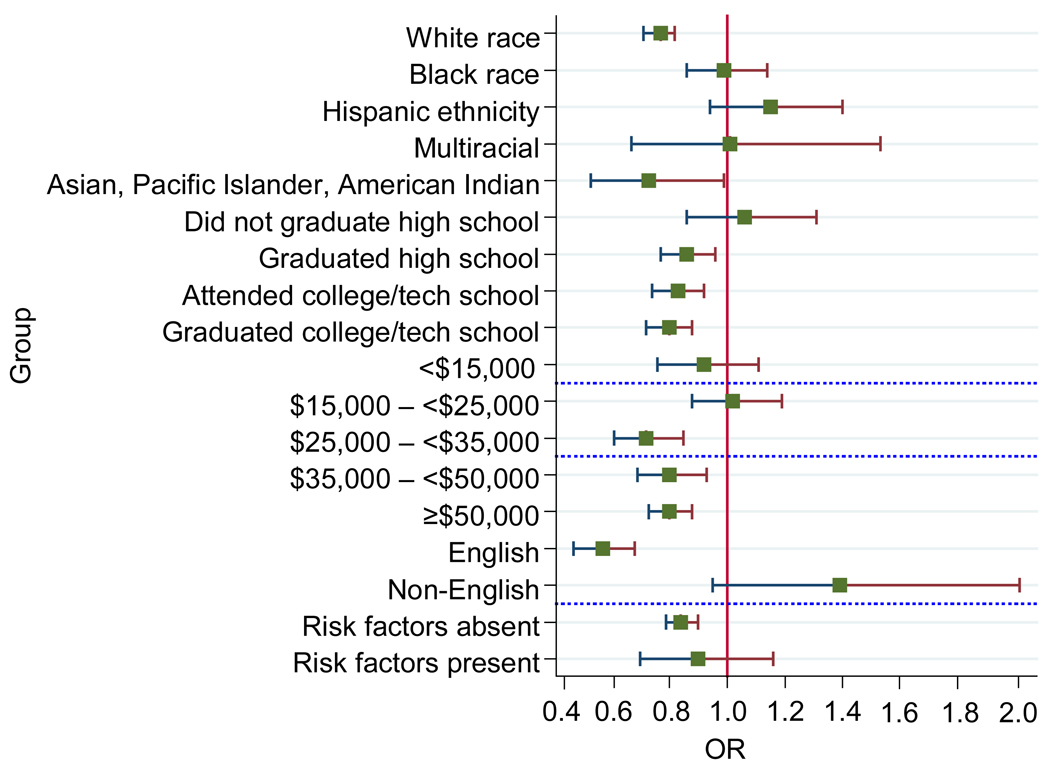

Third, evidence of effect modification was also assessed by race/ethnicity, education, income, health insurance–coverage status, language, and presence of HIV risk behaviors (Figure 1). These calculations are useful to determine if the presence of a written informed-consent statute has more influence on levels of testing among people who have higher levels of education than among those who have lower levels of education. To perform these regressions, race/ethnicity was not included in the calculations on language preference, because the two variables were collinear. As part of a sensitivity analysis, the results of a model that reclassified two states—California and Illinois—as requiring written informed consent were examined. These two states had particularly complex statutes regarding written consent in general medical settings that made them difficult to categorize definitively.

Figure 1.

Residence in a state with a written informed-consent statute and self-reported HIV testing history (by respondent characteristic)

Note: This figure is derived from a series of logistic regressions in which the first subgroup within each category was used as the reference group. The data shown are linear combinations. They are calculated by multiplying the regression coefficient of consent laws X the interaction coefficient of the consent laws X the given subgroup. The combinations can be calculated for both the reference subgroup and the remaining subgroups.

Results

The BRFSS in 2004 had responses from 303,822 people. In total, 227,326 (75%) met the required criteria for age and state of residence. Among these, 209,903 (92%) were willing to respond to questions about HIV testing. Of these respondents, 87,120 (42%) reported having ever been tested for HIV outside of blood donations, and 28,612 (14%) reported having been tested in the 12 months prior to the survey. After taking into account sampling weights, about 17% of respondents reported that they had been tested for HIV in the prior 12 months.

As of 2004, ten states had enacted a statute requiring written informed consent prior to a patient’s undergoing HIV testing: Hawaii (which was excluded from this analysis), Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. According to the 1998 and 2004 compilations of HIV-related state statutes published by Law & Sexuality, none of the statutes relating to written informed consent changed between 1998 and 2004.19,20

In bivariate analysis, women who were aged 18–24 years; described themselves as black, Asian, multiracial, or of Hispanic ethnicity; had a lower education; had a lower income; were without health-insurance coverage; were not in a committed relationship; and had at least one risk factor for HIV were relatively more likely to report being tested for HIV in the 12 months prior to the survey. States were also ranked according to the prevalence of AIDS per capita. The sample was then split into two groups (high and low AIDS prevalence per capita). Respondents living in states with a higher prevalence of AIDS per capita were more likely to report a recent HIV test than respondents living in states with a lower prevalence of AIDS per capita (18.3% vs 12.5%, respectively).

Overall, respondents living in a state with a statute requiring written informed consent were slightly less likely to report a recent HIV test than respondents living in states with no such statute (16.3% vs 16.8%, respectively). While this finding was not significantly different from no association in unadjusted analysis (OR=0.96; p=0.081, 95%CI=0.91, 1.10; Table 1), its significance increases with adjusted analysis. Incorporating all of the individual- and state-level covariates into the model leads to a firmer inverse association between the presence of state-mandated written consent and the likelihood of an individual’s reporting an HIV test in the prior 12 months (OR=0.85; p<0.001, 95% CI=0.80, 0.90).

The average marginal effect—the average of the discrete change for the full sample—was also estimated for residing in a state with a statute requiring written informed consent compared to residing in a state without such a statute. The average partial effect was −0.02 (p<0.001, 95% CI= −0.03, −0.01)—that is, the probability that an individual reports having had a recent HIV test will be 2 percentage points lower in states with a statute requiring written informed consent than in states without such a statute. If the baseline percentage (or probability) of individuals reporting no recent HIV testing is 16.8% in states without a written informed-consent statute, then written informed-consent statutes are associated with an 11.9% reduction in HIV testing, based on the estimated average marginal effects.

The association between written informed-consent requirements and testing differed according to the respondent’s self-reported HIV risk factors, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment (p-values for interaction=<0.001). Those living in a state with a requirement for written informed consent were significantly more likely to report a recent HIV test if they self-reported having an HIV risk factor compared to those who did not report such risk factors. Living in a state with a requirement for written informed consent was also associated with significantly lower rates of testing among respondents who were non-Hispanic white (OR=0.77; 95% CI=0.71, 0.82) or Asian (OR=0.73, 95% CI=0.53, 0.99) but not among respondents who were non-Hispanic black (OR=0.99; 95% CI=0.86, 1.14) or Hispanic (OR=1.14; 95% CI=0.94, 1.40). Similarly, the association between living in a state with a requirement for written informed consent and lack of testing varied according to a respondent’s level of education: The effect of a requirement for written informed consent was greater among respondents with higher levels of educational attainment (OR=0.79; 95% CI=0.72, 0.88 among college/technical school graduates) than respondents with lower levels of educational attainment (OR=1.06; 95% CI=0.86, 1.31 among non–high school graduates).

The results from the sensitivity analysis were similar. When states requiring written informed consent in more restricted medical settings were added to the group of states requiring written informed consent in all settings, the association remained negative between the presence of state-mandated written informed consent and the likelihood of an individual’s reporting an HIV test in the prior 12 months (OR=0.87; p<0.001, 95% CI=0.82, 0.92).

Finally, the analyses were also conducted including data for Washington DC (which was excluded because data were not available on federal funding for HIV prevention). Including these additional 2979 respondents in the analyses did not change the main results.

Discussion

Residents of a state with a statute requiring written informed consent for HIV testing were less likely to report HIV testing in the previous year than residents of a state without such a statute. Subgroups where this relationship was strongest were respondents who denied HIV risk behaviors and those who were non-Hispanic white or had higher levels of education. Because of the increased time associated with explaining and completing the written consent, providers may be offering testing only to those who appear most at risk (e.g., those reporting HIV risk behaviors). Whites and those with higher levels of education may be similarly perceived to be at lower risk for HIV infection. The findings of this study provide some of the first empirical evidence about the relationship between requirements for written informed consent prior to HIV testing and testing rates.

This study is one of only a few analyses of the relationship between state statutes and levels of HIV testing; it is the first such analysis in nearly 20 years. A similar study by Phillips11 examined the 1988 AIDS Knowledge and Attitudes Survey of more than 20,000 people and found that individuals living in states with policies protective of individual rights (i.e., statutes against discrimination and in favor of voluntary and anonymous testing) were 1.5 times more likely to have obtained a test than individuals in comparison states. A more-recent analysis9 found a 33% increase in monthly HIV testing rates following the elimination of a written informed-consent requirement in San Francisco. The results of the current effort are more consistent with this second, more-recent study.

While both this current research and the San Francisco study have methodologic limitations that reduce the strength of their conclusions, taken together they suggest that removing written informed-consent requirements could lead to increased rates of HIV testing, particularly for those without traditional HIV behavior or demographic risk factors. The mechanism whereby written informed consent could result in reduced testing may be that clinicians are less likely to offer testing to those whom they perceive to be not at high risk. However, reliance on assessments of a patient’s risk has been documented to lead to many missed opportunities for identification of HIV-infected individuals.24–26 The CDC aims to eliminate risk-based testing with its new routine-testing recommendations. The results presented here suggest that eliminating written informed-consent statutes might be an important operational approach to implementing those recommendations.

It is important to interpret these results within the larger context of the CDC’s push for routine HIV testing and the inherent contradiction between the recent testing recommendations and state statutes requiring written informed consent. In the setting of a rapidly expanding HIV epidemic and the general privacy protections afforded by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the CDC and others have concluded that the civil rights and ethical dilemmas surrounding consent for HIV testing may be outweighed by public health need and improved access to life-saving therapies.27–31 Their argument is bolstered by studies that have demonstrated the cost effectiveness of routine screening.32–34 However, some patient advocates feel strongly that the information provided prior to testing is critical to good health care. They suggest that the pre-test counseling that may accompany consent is a rare opportunity to educate a high-risk audience about HIV, the meaning of the test results, and methods of preventing future infections.35

Limitations

This study used variation in state statutory written informed-consent requirements to assess the relationship between them and self-reported HIV testing history. Adjustments for many potential individual-level and state-level confounders were included, but it remains possible that unmeasured confounders may influence the observed association.

There are three potential confounders that are particularly relevant. First, states with established laws that mandated written informed consent may also have active AIDS-advocacy groups that encourage testing activities in their states. Second, data were not available on nonfederal funding sources, on Medicaid coverage, and on insurance reimbursement for HIV testing in private settings. Lack of reimbursement for providers could be a significant barrier to HIV testing.

Third, many states require some version of pre-test counseling, post-test counseling, or both, with or without concurrent written pre–HIV test consent. These multiple variations of consent and counseling defied simple categorization among the states included in the study. If any of these or other confounders were present, excluding them could have biased the estimate of the true effect of consent statutes on testing rates. In addition, telephone-based surveys have known limitations regarding representativeness, and the 2004 BRFSS had a median response rate of only 52.7%. The results therefore may not be representative of all residents of the states studied.

The findings of this study are further limited by both recall bias—people who had to sign consent forms may be more likely to recall being tested—and misclassification bias. The misclassification bias could occur because of the variation among states’ policies requiring written consent prior to HIV testing. Some policies may not appear in statutes, and the interpretation and enforcement of the requirements of those that do may vary among states. Also, significantly, no information was available about individual physicians’ or patients’ awareness of the statutes in their states or the extent to which this knowledge influences their actions.36 To limit misclassification, an exclusive definition of written consent was utilized, focusing particularly on statutes that would influence what might actually occur in a physician’s office—where most people prefer to undergo testing.37 Recall and misclassification bias are likely to drive the effect estimate toward the null, however, suggesting that the results reported here are conservative.

There also could be a concern that using state-level statute data to make inferences about individual behavior may lead to biased estimates. The study is not subject to problems of ecologic analysis, because all respondents within each state were exposed to its particular statute. Thus, if a respondent lived in a state where a statute was in place, then the respondent was exposed; otherwise, he or she would not have been exposed.

Conclusion

The CDC first promoted routine HIV testing in medical settings in 1993 for high-prevalence communities.38 However, those guidelines largely were not implemented, perhaps due to two important factors: first, HIV’s exceptionalism as a disease and the resulting stigma that many providers and patients attached to the testing process10; and second, operational barriers to HIV testing, such as burdensome counseling and consent processes.39 In the face of an expanding but now-treatable epidemic, the CDC decided to encourage more testing in 2006 by recommending the removal of separate written informed consent prior to HIV testing. Although there are many barriers to increasing HIV testing that might be as important—or more important—than written informed-consent statutes, the findings of this study suggest that the removal of written informed-consent requirements might promote the non–risk-based routine-testing approach that the CDC advocates in its new guidelines. By early 2008, five of the ten states (Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania) with written informed-consent requirements had begun the process of removing or revising their legislation regarding HIV testing. Maine’s governor had signed a new law into effect in May 2007. The other states have seen amendments introduced. It is hoped that this study will add to the policy debate in those states and lead to the opening of the debate in the remaining states with the requirement.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the biostatistical support of Jeremy Kahn, MD, MS, and the reviewing assistance of Melani Sherman, BA, and Rachael Truchil, BA. Each of these individuals is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. They would also like to acknowledge the advising efforts of Theoklis Zaoutis, MD, MSCE, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The principal investigator, Peter Ehrenkranz, MD, MPH, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors has financial interests, relationships, or affiliations relevant to the subject of the manuscript. The work was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and its support of the Clinical Scholars Program. Dr. Linas acknowledges the financial support of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number K01AI073193).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS—U.S., 1981–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(21):589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neal J, Fleming PL. Frequency and predictors of late HIV diagnosis in the U.S., 1994 to 1999; Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle WA: 2002. Feb 24–28, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the U.S.: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, et al. Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(7):734–740. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.No time to lose: getting more from HIV prevention. Washington DC: IOM, National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses—33 states, 2001–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(45):1149–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR14):1–17. quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers JE, Henning KJ, Frieden TR, Larson K, Begier B, Sepkowitz KA. Written consent for human immunodeficiency virus testing. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(4):433–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zetola NM, Klausner JD, Haller B, Nassos P, Katz MH. Association between rates of HIV testing and elimination of written consents in San Francisco. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1061–1062. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer R. Public health policy and the AIDS epidemic. An end to HIV exceptionalism? N Engl J Med. 1991;324(21):1500–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips KA. The relationship of 1988 state HIV testing policies to previous and planned voluntary use of HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7(4):403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, et al. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the U.S. Med Care. 2006;44(11):990–997. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman RE. Current CDC guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral: critical role of and a call to action for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain CSJ, Jones S, Wyatt C, Wallach F, Mackay R, Jones S. Barriers to HIV testing in a large, urban academic medical center; Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Denver CO: 2006. Feb 5–8, [Google Scholar]

- 15.USDHHS Office of the Inspector General. Reducing obstetrician barriers to offering HIV testing. Washington DC: USDHHS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troccoli K, Pollard H, 3rd, McMahon M, Foust E, Erickson K, Schulkin J. Human immunodeficiency virus counseling and testing practices among North Carolina providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):420–427. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fincher-Mergi M, Cartone KJ, Mischler J, Pasieka P, Lerner EB, Billittier AJ., 4th Assessment of emergency department health care professionals’ behaviors regarding HIV testing and referral for patients with STDs. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16(11):549–553. doi: 10.1089/108729102761041100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Atlanta GA: USDHHS, CDC; Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey data. 2004 www.cdc.gov/BRFSS/.

- 19.Tulane University School of Law. A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender legal issues. Law & Sexuality. 1998;8:3–526. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tulane University School of Law. A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender legal issues. Law & Sexuality. 2004;13:5–603. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barron P, Goldstein SJ, Wishnev KL. State statutes dealing with HIV and AIDS: a comprehensive state-by-state summary. Law & Sexuality. 1995;5:1–512. [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance report: cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the U.S., 2004. Atlanta GA: USDHHS, CDC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linas BP, Zheng H, Losina E, Walensky RP, Freedberg KA. Assessing the impact of federal HIV prevention spending on HIV testing and awareness. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, Samet JH. Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection—South Carolina, 1997–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(47):1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, Cohn DL, Burman WJ. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(5):329–333. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194617.91454.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayer R, Fairchild AL. Changing the paradigm for HIV testing—the end of exceptionalism. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):647–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frieden TR, Das-Douglas M, Kellerman SE, Henning KJ. Applying public health principles to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(22):2397–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gostin LO. HIV screening in health care settings: public health and civil liberties in conflict? JAMA. 2006;296(16):2023–2025. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo DJ, Begier EM, Henn MH, Sepkowitz KA, Kellerman SE. HIV counseling and testing: less targeting, more testing. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):962–964. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.089235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo B, Wolf L, Sengupta S. Ethical issues in early detection of HIV infection to reduce vertical transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(2S):S136–S143. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012152-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paltiel AD, Weinstein MC, Kimmel AD, et al. Expanded screening for HIV in the U.S.—an analysis of cost-effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):586–595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Sundaram V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):570–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paltiel AD, Walensky RP, Schackman BR, et al. Expanded HIV screening in the U.S.: effect on clinical outcomes, HIV transmission, and costs. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(11):797–806. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tytel J. Letter from national organizations responding to AIDS. Washington DC: National Organizations Responding to AIDS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burris S. Driving the epidemic underground? A new look at law and the social risk of HIV testing. AIDS Public Policy J. 1997;12(2):66–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser Family Foundation. Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS. Washington DC: The Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.CDC. Recommendations for HIV testing services for inpatients and outpatients in acute-care hospital settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42(RR2):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burke RC, Sepkowitz KA, Bernstein KT, et al. Why don’t physicians test for HIV? A review of the U.S. literature. AIDS. 2007;21:1617–1624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32823f91ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]