Abstract

Syringolins are a class of cyclic tripeptide natural products that are potent and irreversible inhibitors of the eukaryotic proteasome. In addition to being hybrid NRPS/PKS molecules, they also feature an unusual ureido-linkage (red) between two amino acid monomers. Here we report the first in vitro characterization of enzymatic ureido-linkage formation which is catalyzed by an NRPS, SylC. Using 13C- and 18O-labeling studies, we show that biosynthesis occurs via N-carboxylation to form an initial N-carboxy-aminoacyl-S-Ppant enzyme intermediate which undergoes intramolecular cyclization followed by condensation with a second amino acid to form the ureido-containing dipeptide product.

Nonribosomal peptide (NRPS) and polyketide synthetases (PKS) utilize numerous chemical reactions with precise control of regio- and stereochemistry on activated, tethered intermediates to construct diversely functionalized natural products with broad biological activity.1 Typically these events occur through a controlled chain-elongation process where peptide and/or carbon-carbon bonds are constructed in an iterative manner. In NRPS the peptide scaffold is formed through successive assembly of amide bonds in a manner where chain polarity remains unidirectional. However, N-to-N terminal condensation via an ureido-linkage leads to a reversal of chain polarity and introduces a new point of diversification to modulate biological activity.

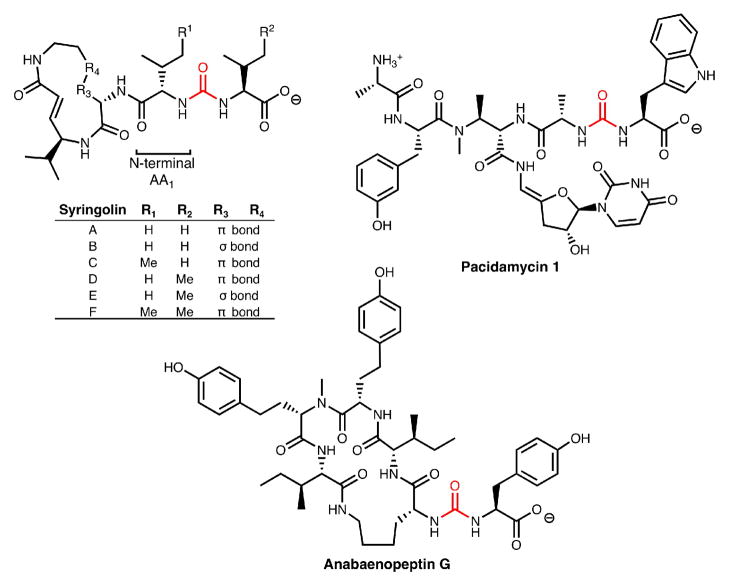

The syringolin family of proteasome inhibitors are NRPS-PKS hybrid molecules with notable structural features including a 12-membered ring and N-terminal acylation via a ureido-linkage.2a In syringolin A, Val1 is N-acylated by an additional valine in a head to head condensation creating a ureido-linkage and affording a negative terminus rather than the usual positive terminus. Other natural products containing a chain reversal by way of a ureido-linkage include the anabaenopeptins,2b brunsvicamides,2c pacidomycins,2d mureidomycins,2e and napsamycins2f (Figure 1). Although the specific biological ramifications of chain reversal remain unknown at this time, N-acylation is known to dramatically influence the efficacy of syringolin A as a proteasome inhibitor.3

Figure 1.

Ureido-containing natural products.

Syringolin A was first isolated from P. syringae and characterized in 1998 by Dudler and coworkers as an elicitor of stress response in rice, aiding in resistance toward the phytotoxic fungi, P. oryzae.2a Recent studies have shown that the active site Thr1 of the 20S eukaryotic proteosome interacts covalently and irreversibly with the α,β-unsaturated amide of the syringolin macrocylic core via a Michael addition mechanism.4 The resulting inhibition is consistent with studies that show syringolin-induced cell death of neuroblastoma, ovarian,5a and leukaemic5b cancer cells. The combined biomedical relevance and unusual ureido-functionality led us to examine the formation of this linkage in syringolin biosynthesis.

Recent in vivo investigations by Dudler and coworkers into the biosynthetic origin of the ureido-linkage of syringolin A revealed integration of either bicarbonate or carbon dioxide.6 Feeding studies with [13C]-bicarbonate followed by product characterization validated that incorporation was restricted to the carbonyl moiety. In this study we have focused on in vitro characterization of SylC, the NRPS enzyme presumed responsible for syringolin chain initiation, to evaluate its role, in generation of the ureido-linkage subsequent to amino acid monomer activation.

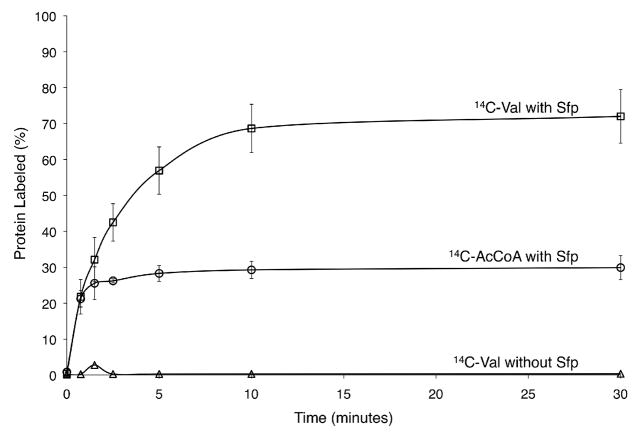

The full-length sylC gene was amplified from P. syringae B728a and cloned into E. coli expression vectors to generate a 147-kDa His6-tag fusion. Overexpression and Ni-NTA purification provided soluble SylC, with the thiolation (T) domain in the apo-form as confirmed by subsequent phosphopantetheinylation with acetyl-coenzyme A (AcCoA) and the promiscuous phosphopantetheinyl transferase, Sfp.7 The SylC adenylation (A) domain was first assayed using ATP-PPi exchange, and both L-Val and L-Ile were preferentially reversibly adenylated.8 Additionally, L-Thr and L-allo-Ile were also activated but at approximately 40% the level of the natural substrates (Figure S2). The covalent loading of amino acid monomers onto the SylC thiolation (T) domain was next investigated. Calibration experiments utilizing Sfp and radiolabeled [1-14C]-AcCoA demonstrated that ~30% of SylC could be labeled during conversion from the apo-form to the holo-form by installation of the phosphopantetheinyl (Ppant) group on the T-domain (Figure 2, circles).9 Intriguingly, when the HS-Ppant holo-form of SylC enzyme was formed by prior incubation with Sfp and unlabeled CoA and then subjected to amino acid loading via ATP and [1-14C]-L-valine, approximately twice the level of radiolabeled protein was detected (Figure 2, squares). These results indicated that two equivalents of valine were incorporated into a single SylC enzyme and thus provided the first indication that SylC was in fact generating the ureido-Val-CO-Val-S-SylC as a covalently tethered thioester intermediate. [1-14C]-L-Ile was also successfully loaded onto SylC at lower fractional stoichiometry, while the formation of [1-14C]-Thr-S- SylC was not observed (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Comparison of extent of conversion from apo-SylC to holo-SylC by Sfp (circles) to extent of [14C]-L-Val loading onto the holo-SylC T-domain (squares). SylC is isolated entirely in the apo-form as indicated by no [14C]-L-Val loading if Sfp is omitted from the assay (triangles).

To verify formation of the thioester bound Val-CO-Val moiety on the T-domain of SylC we turned to high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). HRMS was utilized due to the accumulation of only picomolar quantities of the ureido-peptidyl-S-T intermediates as a result of the single turnover process. Quenching the assays with hydroxide, which hydrolyzed the T-domain thioester, allowed for the identification of the released ureido-dipeptides by their corresponding masses.

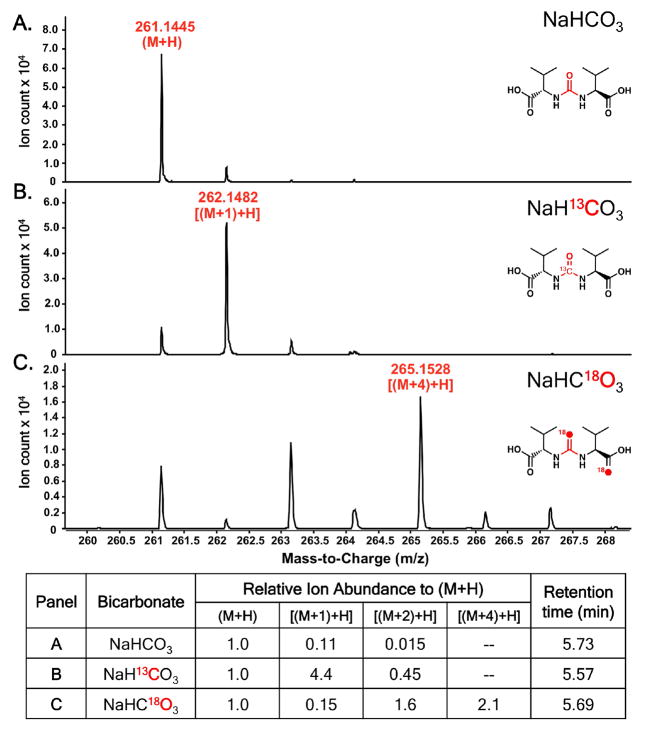

In vitro assays with ATP, bicarbonate, L-Val and/or L-Ile, and SylC, followed by hydrolytic release of the peptidyl-S-T domain intermediates, gave all three of the ureido-dipeptides (Val-CO-Val, Figure 3A; Val-CO-Ile, Ile-CO-Ile, Figure S5). Additionally, the enzyme accepted and processed L-allo-Ile, presumably an unnatural substrate, producing the symmetric ureido-product (Figure S6). Next, [13C]-bicarbonate was utilized as a chemical probe in SylC incubations to validate the carbon source of the carbonyl moiety of the ureido-linkage. The appearance of a [M+1] mass peak by HRMS corroborates the feeding studies of Dudler and coworkers and confirms that SylC alone forms the ureido-linkage from a bicarbonate source (Figure 3B).6

Figure 3.

HRMS of the A) unlabeled valine ureido-dipeptide, B) [13C]-labeled valine ureido-dipeptide, and C) [18O]-labeled valine ureido-dipeptide with normalization of ion abundance shown below.

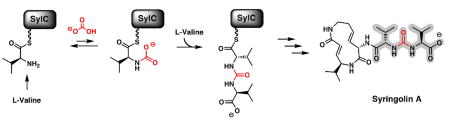

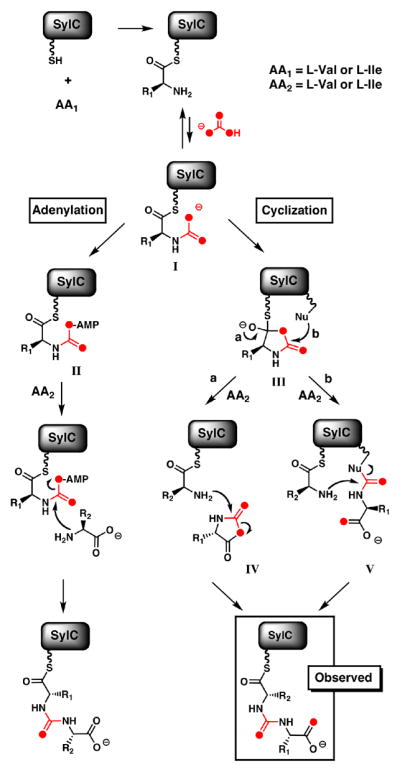

These studies establish that SylC, a free-standing NRPS module with a single C, A and T-domain, can activate L-Val or L-Ile twice and effect the chain reversal step to build the ureido-linkage on the HS-Ppant arm of its T-domain. This constitutes novel chemistry for an NRPS module, and the lack of precedent led us to question the mechanistic details of ureido-linkage formation. We hypothesized that the SylC A-domain conventionally activates one equivalent of amino acid as the aminoacyl-AMP, which is then captured by the thiol of the Ppant arm and loaded as the thioester onto the T-domain (Val-S-T SylC, Figure 4). It is likely that carboxylation of the amine of the tethered aminoacyl moiety by either bicarbonate or, more likely, carbon dioxide next forms a transient N-carboxy adduct, I. Examples of stabilized N-carboxy amines are known to participate in the catalytic mechanisms of RuBisCO10a and class D β-lactamases.10b

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanisms of SylC-catalyzed formation of the ureido-dipeptide showing two distinct pathways (adenylation and cyclization) which are distinguished by label incorporation when the reaction is carried out with [18O]-bicarbonate.

Formation of I would be followed by one of several possible transformations (Figure 4). The “adenylation” pathway involves N-carboxy-amino acid adenylation to form an activated mixed anhydride II, which would then react with a free amino acid forming the resulting ureido-dipeptide. Alternatively, in the “cyclization” pathway, the N-carboxy intermediate would cyclize intramolecularly, to generate a highly reactive covalently tethered thiohemiacetal intermediate, III. This transient thiohemiacetal would partition in one of at least two ways. In one scenario, formation of a “Leuch’s anhydride” of type IV11 would persist as a non-covalently bound species in the SylC active site during activation and loading of the second Val (Figure 4, pathway a). The nucleophilic amine of the second Val-S-T intermediate would capture IV regiospecifically and unravel it to the ureido-peptidyl-S- SylC.12 Alternatively, the transient thiohemiacetal III would be intercepted first by a nucleophilic SylC residue (Nu) to form a covalent adduct V (Figure 4, pathway b).13 This in turn would be captured by the nucleophilic amine of the second tethered Val yielding the ureido-dipeptide. Presumably, the ureido-peptidyl-S-SylC serves as the upstream intermediate that is transferred to the next NRPS module during chain elongation in syringolin biosynthesis.

To distinguish between adenylation or cyclization mechanisms we chose [18O]-bicarbonate as a probe, since the adenylation pathway of Figure 4 would result in an [M+2] product while both arms of the cyclization pathway would furnish an ureido-dipeptide with an enrichment of [M+4].14 SylC incubations were performed in [18O]-bicarbonate/[18O]- water (80% total 18O enrichment) after which the protein was precipitated with MeOH and the pellet washed three times to remove [18O]-water and [18O]-bicarbonate. The thioester-bound intermediates were released by chemical hydrolysis in unlabeled water and analyzed by HRMS. Inspection of this data shows clear enrichment of the [M+4] mass peak (Figure 3C). Notably, one of the two [18O] atoms is incorporated into the amino acid carboxylate (Val), while the other is presumably localized in the ureido-group (Figure S9); the separation of the two oxygen atoms is fully consistent with intramolecular cyclization of the N-carboxyaminoacyl-S-T species (I). Capture of a Leuch’s anhydride IV or the covalent adduct V could equally account for the incorporation and placement of two [18O] atoms in ureido-products.

In summary, we have completed the first in vitro characterization of enzymatic ureido-linkage formation. SylC, with a single C, A and T-domain, iteratively activates two amino acid monomers and constructs the ureido-linkage by incorporation of bicarbonate/CO2 by cyclization of an initial N-carboxy-aminoacyl-S-Ppant enzyme intermediate.

Future studies will be directed at deducing evidence in favor of these or alternate mechanisms for formation of the ureido-group and evaluating parallel systems for the peptide chain reversal in pacidamycins and anabaenopeptins. The mode of action of syringolin A is similar to that of the anti-cancer drug Velcade15 and presents an opportunity to expand the proteasome inhibitor class of cancer therapeutics. We anticipate that exploration of the promiscuity inherent to SylC, as evidenced by formation of the unnatural L-allo-Ile-containing ureido-dipeptide, should allow for the production of new syringolin analogues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM49338 (C.T.W.). The authors would like to thank Prof. S. Lindow at UC-Berkeley for supplying the B728a strain of P. syringae and Prof. R. Dudler at the University of Zurich for discussion of results prior to publication.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supplemental figures, experimental procedures, and HRMS characterization. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Cane DE, Walsh CT, Khosla C. Science. 1998;282:63. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Waspi U, Blanc D, Winkler T, Ruedi P, Dudler R. Mol Plant- Microbe Interact. 1998;11:727. [Google Scholar]; Amrein H, Makart S, Granado J, Shakya R, Schneider-Pokorny J, Dudler R. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004;17:90. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Harada KI, Mayumi T, Shimada T, Suzuki M, Kondo F, Watanabe MF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:6091. [Google Scholar]; (c) Walther T, Renner S, Waldmann H, Arndt HD. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:1153. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chem RH, Buko AM, Whittern DN, McAlpine JB. J Antibiot. 1989;42:512. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Isono F, Sakaida Y, Takahashi S, Kinoshita T, Nakamura T, Inukai M. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1203. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chatterjee S, Nadkarni SR, Vijayakumar EK, Patel MV, Ganguli BN, Fehlhaber HW, Vertesy L. J Antibiot. 1994;47:595. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clerc J, Groll M, Illich DJ, Bachmann AS, Huber R, Schellenberg B, Dudler R, Kaiser M. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901982106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groll M, Schellenberg B, Bachmann AS, Archer CR, Huber R, Powell TK, Lindow S, Kaiser M, Dudler R. Nature. 2008;452:755. doi: 10.1038/nature06782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Coleman CS, Rocetes JP, Park DJ, Wallick CJ, Warn-Cramer BJ, Michel K, Dudler R, Bachmann AS. Cell Prolif. 2006;39:599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Clerc J, Florea BI, Kraus M, Groll M, Huber R, Bachmann AS, Dudler R, Driessen C, Overkleeft HS, Kaiser M. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2638. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramel C, Tobler M, Meyer M, Bigler L, Ebert M-O, Schellenberg B, Dudler R. BMC Biochemistry. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-26. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambalot RH, Gehring AM, Flugel RS, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel MA, Reid R, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Reuter K, Mofid MR, Marahiel MA, Ficner R. Embo J. 1999;18:6823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen JB, Hsu M-J, Byrne KM, Kaplan L. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5789. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linne U, Marahiel MA. Methods in Enzymology. 2004;388:293. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Lorimer GH, Miziorko HM. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5321. doi: 10.1021/bi00564a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li J, Cross JB, Vreven T, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S, Schlegel HB. Proteins. 2005;61:246. doi: 10.1002/prot.20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirschmann R, Strachan RG, Schwam H, Schoenewaldt EF, Joshua H, Barkemeyer B, Veber DF, Paleveda WJ, Jacob TA, Beesley TE, Denkewalter RG. J Org Chem. 1967;32:3415. doi: 10.1021/jo01286a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leuch anhydrides have been utilized as peptide coupling reagents, however no dipeptide or resulting diketopiperazines were observed as side products from SylC incubations by HRMS.

- 13.Wong BJ, Gerlt JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12076. doi: 10.1021/ja037652i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.18O-enrichment represented by the filled oxygens.

- 15.Groll M, Berkers CR, Ploegh HL, Ovaa H. Structure. 2006;14:451. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.