Abstract

The global market for monoclonal antibody therapeutics reached a total of $11.2 billion in 2004, with an impressive 42% growth rate over the previous five years and is expected to reach ~$34 billion by 2010. Coupled with this growth are stream-lined product development, production scale-up and regulatory approval processes for the highly conserved antibody structure. While only one of the 21 current FDA-approved antibodies, and one of the 38 products in advanced clinical trials target infectious diseases, there is increasing academic, government and commercial interest in this area. Synagis, an antibody neutralizing respiratory syncitial virus (RSV), garnered impressive sales of $1.1 billion in 2006 in spite of its high cost and undocumented effects on viral titres in human patients. The success of anti-RSV passive immunization has motivated the continued development of anti-infectives to treat a number of other infectious diseases, including those mediated by viruses, toxins and bacterial/fungal cells. Concurrently, advances in antibody technology suggest that cocktails of several monoclonal antibodies with unique epitope specificity or single monoclonal antibodies with broad serotype specificity may be the most successful format. Recent patents and patent applications in these areas will be discussed as predictors of future anti-infective therapeutics.

Keywords: antibody engineering, passive immunization, neutralizing antibody, immune sera, RSV, anti-toxin, botulism, clostridia, anthrax, polyclonal, oligoclonal, toxins, targeted delivery, anti-viral

Introduction

Antibodies have been used to bind and inactivate pathogenic material for over 100 years, originally being isolated as polyclonal antibody mixtures from immunized horse serum. This “passive immunotherapy” was used successfully to treat many viral and bacterial infections but due to numerous problems, including product heterogeneity and low specific titre, coupled with risks of immunogenicity and viral contamination, lost favor after the introduction of antibiotics [1]. More recently, the emergence of antibiotic resistant microorganisms, emerging viruses and the threat of engineered micro-organisms coupled with advances in understanding pathogenic mechanisms and antibody technology leaves this class of therapeutics poised for a comeback [1, 2].

Antibodies are attractive anti-infective therapeutics for their ability to recognize a ligand molecule associated with exquisite specificity and to recruit additional immune system components such as complement and natural killer cells, facilitating pathogen inactivation and removal. When properly designed, an antibody can effectively block pathogen recognition of cellular targets, thereby interrupting the infectious cycle. Here we review representative patents and patent applications with the potential for treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases.

Anti-viral antibodies

Anti-virals remain a healthy market, with numerous small molecules and antibody based therapeutics in development and the primary emphasis on HIV and hepatitis B and C [3]. This is partly because of the need for treatments in these areas and the continuing effectivity of the 17 polyclonal human immunoglobulin preparations available in the US [4]. Major challenges when designing antibody therapies against viruses include identification of potently neutralizing epitopes which are conserved across serotypes and the potential for rapidly evolving viruses to generate escape variants which are no longer inhibited by the antibody. Combination therapies, either an antibody co-administered with a small molecule (i.e., ribavirin) or a combination of neutralizing antibodies binding distinct epitopes can address these issues.

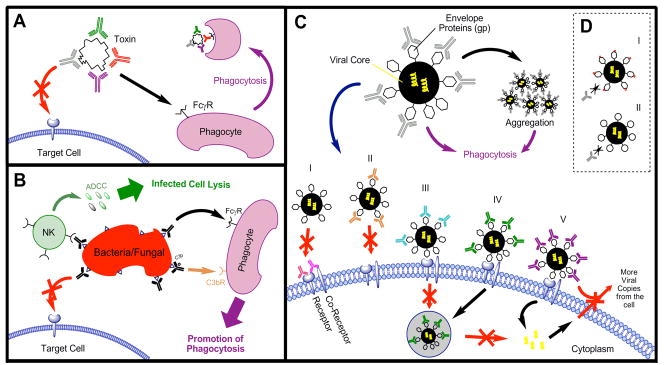

The mechanism(s) by which immunoglobulins neutralize viral particles in vivo has not been elucidated in many cases, even those for which immune sera is used routinely. Possible mechanisms include: (1) steric hindrance of the interaction between viral glycoprotein and host cell receptor [5], (2) reduction of infectious “units” by rafting, that is – antibody-mediated cross-linking multiple infectious units into a single infectious unit, (3) opsonization of infectious virus particles, and (4) antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC, destruction of infected cells), (5) complement (see Figure 1). Of particular interest is the role of the Fc in protection, as the latter two mechanisms are dependent upon this domain. For instance, it has been reported that rat IgG2a but not IgG1 or F(ab′)2 antibodies specific for the same LCMV GP1 epitope are protective in vivo [6].

Figure 1.

A, Anti-Infective Mechanism of Antibodies for Inhibition of Toxin B by blocking access to Target Cell and facilitate toxin removal; B, Inhibition of Bacterial/Fungal Bodies by blocking cellular binding and removal through natural killer cells or phagocytes; C, Inhibition of Virals (adapted from Marasco, 2007) - i. mAb bound to co-receptor or combination prevents target cell interaction; ii. mAb bound to EnV prevents blocks target cell interaction; iii. mAb bound to Env binds but prevents endosome formation; iv. mAb bound to EnV prevents release from endosome; v. mAb bound to EnV prevents release of replicated viral RNA from the target cell; D, Viral Escape from antibodies via i) EnV mutation; ii) EnV conformational change.

Very broad range anti-viral antibodies

The “holy grail” anti-viral antibody would be one which targets a generic aspect of viral pathogenesis, an antibody that could be used to treat a wide range of viral infections without the need to diagnose the specific virus responsible for infection or concern over development of escape variants. One antibody with this potential has been reported in US patent 7,455,833, an anti-phospholipid antibody marketed as Bavituximab by Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Normally, eukaryotic cell lipid bi-layers contain phosphatidylserine only on the inner leaflet, where it is inaccessible to circulating antibodies. However, virus-induced activation and virally-induced apoptosis events result in a loss of lipid asymmetry, with phosphatidylserine appearing on the outer, exposed leaflet. Antibodies binding exposed PS appear to limit viral infection by removing enveloped viruses from the bloodstream and inducing antibody-dependant cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) to eliminate virally-infected cells. Phase I clinical trials have been completed for patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and are currently underway for those co-infected with HIV and HCV. A recent study [7] demonstrated the effectivity of anti-PS antibodies for animals infected with CMV (100% treated mice survived versus 25% untreated mice) as well as those infected with the Pichinde arenavirus (50% treated animals survived, none of the untreated survived). A second, potentially generic approach is outlined in US patent 2008/0248042, describing a bi-specific antibody which binds an infectious agent (including HCV, CMV and others) with one arm and the IgG Fc region between amino acids 345-355 with the other arm. This antibody-mediated cross-linking of virion and B cell results in a strengthened B cell response against the pathogen.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

By the time most humans have reached adulthood, they have been exposed to CMV, with approximately 70% becoming asymptomatic carriers. However, individuals with compromised immune systems due to HIV infection or organ transplantation can suffer invasive CMV infection, leading to transplant rejection, opportunistic infections and organ failure [8]. CytoGam®, a human immune globulin preparation enriched in anti-CMV antibodies originally developed by MedImmune (now owned by CSL Behring), has been marketed for over ten years showing significant reductions in CMV-related illness but not asymptomatic carriage. In spite of Cytogam’s success, the potential role for monoclonal antibody therapy is not clear (see Table 1 for a comparison). MSL-109 (Sevriumab/Protovir; covered by US Patent 5750106) is a human monoclonal antibody binding CMV glycoprotein H that has been involved in six clinical trials for CMV treatment. This molecule has been explored as treatment for congenital CMV infection in newborns and HIV-immunocompromised patients, primarily to treat CMV retinitis. Although the molecule is potently neutralizing in vitro, there is no correlation between the patient plasma concentration of MSL-109 and virologic or clinical measures in large trials [9]. The explanations for this include: (1) the premature termination of two studies due to an increased mortality rate in the highest dose treatment group, (2) insufficient antibody concentrations in the ocular compartment for retinitis studies, and (3) therapies targeting only the humoural arm of the immune system may be insufficient. Patent WO 2008/120203 addresses this last issue by reporting a TCR-like antibody that binds an MHC molecule displaying CMV peptides pp65 or pp64. As opposed to directly targeting the viral particle, for instance by blocking the initial association between virus and cell, this molecule binds virally-infected cells and by virtue of the antibody Fc region, recruits immune cells to remove infected cells. This approach is intriguing in light of the failures of MSL-109 and that cell-mediated immunity dominates CMV infection control in vivo.

Table 1.

Selected anti-infective antibodies

| Target | Antibody form | Company | Patent # | Stage | Drug name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. anthracis | |||||

| Protective antigen | Medarex, PharmAthene | 7,456,264 | Phase I | MDX-1303 (Valortim™) | |

| Protective antigen | Human mAb | Human genome sciences | 2008/0081042? | Phase I complete | ABthrax |

| Protective antigen | Humanized mAb | Elusys | 6,916,474 | Phase I/II | Anthim, ETI-204 |

| B. pertussis | |||||

| Pertussis toxin | Human pertussis immune globulin | - | Phase III | P-IGIV | |

| Candida | |||||

| Anti-hsp90 with amphotericin B | Human ScFv | NeuTec Pharma | - | Phase III | Mycograb |

| Candida-HP | Elusys, MedImmune | - | Pre-clinical | ETI | |

| C. difficile | |||||

| toxins A, B | Medarex | 2005/0287150 | Phase II | MDX-066 (CDA-1) + MDX-1388 (CDA-2) | |

| CMV | |||||

| CMV | Human immune sera | CSL Behring | approved | Cytogam | |

| Glycoprotein H | Human monoclonal antibody; with gagcyclovir | PDL Pharma/Novartis | US 5750106 | Phase I/II/III | Sevirumab/Protovir, MSL 109 |

| CMV peptide p64 or p65 displayed by MHC | TCR-like antibody | -- | |||

| Anti-phosphatidylserine (broad range anti-viral) | chimeric antibody | Peregrine | 7,455,833 | Phase I complete | Bavituximab |

| E. coli | |||||

| Shiga toxins 1 and 2 | Combination of two mAbs | Thallion | 2007/0160607 2007/0292426 |

Phase I | ShigamAb |

| Hepatitis virus | |||||

| Hepatitis B | Human poly-immunoglobulin | NABI-HB, now Biotest (2007) | - | FDA approved | |

| HIV | |||||

| gp120 | CD4-Ig Fusion Protein | Progenics | Phase II | PRO542 | |

| CD4 | Humanized antibody | Tanox | Phase II | TNX-355 | |

| CCR5 | Humanized antibody | Progenics | Phase II | PRO 140 | |

| CCR5 | Human antibody | Human Genome Sciences | Phase I | CCR5mAb004 | |

| RSV | |||||

| RSV | Polyclonal immunoglobulin | MedImmune | - | Approved, Phase IV | Respigam |

| F-protein | Humanized IgG1 | MedImmune | approved | Synagis, Palavizumab | |

| F-protein | Humanized IgG1 | MedImmune | Phase III | Motavizumab | |

| F- and G-proteins | Human recombinant polyclonal | Symphogen | Sym00 | ||

| S. aureus (MRSA) | |||||

| Staph cell adhesion molecules | Polyclonal human immune sera | Inhibitex | 6692739 | On hold after Phase III | Veronate |

| S. aureus Capsular polysacc types 5 and 8 | Vaccine-induced human hyper-immune sera | NABI Pharmaceuticals | 2006/0153857 A1 | On hold after Phase II | Altastaph |

| ABC transporter (drug efflux pump) | Antibody fragment; synergy with vancomycin | NeuTec | 2007/0202116 | Phase III | Aurograb |

| Clumping factor A (ClfA) | Humanized monoclonal IgG1κ | Inhibitex | 6979446 | Phase IIA | Tefibazumab (Aurexis) |

| Lipoteichoic acid | Human chimeric monoclonal | Biosynexus | 2008/0019976 | Phase II | Pagibaximab (BSYX-A110) |

| Protein A | HP antibody | Elusys, Pfizer | - | Pre-clinical | ETI-211 |

| S. aureus (non-MRSA) HP | Elusys, Medimmune | - | Pre-clinical | ||

Influenza, including H5N1 avian influenza virus (AIV)

Influenza invades cells via the hemagglutinin (HA) protein association with cell surface sialic acid residues, which vary in structure based on the host species and anatomical location. Since the 1918 pandemic influenza outbreak which killed 20–40 million people world-wide, there has been concern that a new strain with similar virulence will emerge. H5N1 avian influenza appears to exhibit pandemic potential (human mortality rates are estimated at 60%), motivating development of specific vaccines and therapeutics.

Patents WO 2007/089753 and WO 2008/140415 describe monoclonal antibodies specific for the H5 variant of the hemagglutinin protein, able to block up to 50% of HA cell-binding, indicating potential utility as an H5N1-specific therapeutic. In contrast, patent WO 2008/028946 covers human antibody CR6261 that exhibits broad serotype specificity, neutralizing six antigenically diverse hemagglutinin subtypes including H5. The antibody, developed by Crucell, was identified from an IgM antibody phage display library generated from B cells of donors recently vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine. The unusual aspects of this patent are that they (1) identified a broadly conserved neutralizing epitope, located in the HA stem domain, and (2) used an IgM repertoire and recovered an antibody with 4 nM affinity [10]. CR6261 was able to protect all mice prophylactically from a 10 LD50 lethal dose and 50% of mice from a 25 LD50 dose when administered four days post-infection (all mock-treated animals succumbed), demonstrating its potential application for broad-range treatment for H5N1 and H1N1 strains.

Hepatitis Virus

While antibodies for Hepatitis A and B have been pursued, most effort has shifted to the Hepatitis C virus. This is due in part to the availability of a protective Hepatitis B vaccine along with the surge in Hepatits C infections occurring concurrently with HIV.

Hepatatis B Virus (HBV)

Chronic hepatitis B infection leads to liver failure and heptacellular carcinoma, accounting for approximately one million deaths each year. This disease is controlled through wide-spread administration of an effective vaccine, with hyper-immune anti-sera (HBIG) prescribed in clinical cases. Clinical trials are currently in process for a combination of the nucleoside analogue lamivudine and HBIG. The results of Nabi-HBR (Nabi Biopharmaceuticals) indicate the combination of lamivudine with lower doses HBIG prevented post liver transplant HBV recurrence for less than 10% the cost of high-dosage HBIG treatments [11]. This treatment can also be used to treat acutely exposed patients. Nabi-HB has been clinically proven at both the phase I and phase IIa trial showing the safety of immune complexes of yeast-derived HBsAg and antibodies [12]. Monoclonal antibodies in earlier stages of development also bind the viral surface antigens. Patent WO 2006/076640 covers a chimpanzee cDNA antibody library used to isolate a neutralizing antibody to HBV. This antibody binds the principle neutralizing epitope of HbsAg and was subsequently humanized.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

HCV also infects the liver, resulting in chronic liver disease, including liver cancer and has become the leading cause for liver transplantation in the US. The World Health Organization estimates approximately 170 million people (3% of world population) are infected with HCV, with 3 – 4 million new cases each year, many co-infected with HIV-1. To date, there are no vaccines available and the best long-term treatment is interferon-alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin. This treatment is rather costly and has shown signs of significant toxicity, spurring development of new therapeutic approaches to combat this virus.

Envelope glycoprotein domains E1 and E2 mediate HCV cellular invasion, with E2 binding the co-receptor CD81 and the scavenger receptor SR-B1 [13]. Efforts in development of HCV neutralizing antibodies currently focus on those that block the binding of domain E2 or the hypervariable region of E2 to CD81 [14]. The antibody covered by patent WO 2008/108918A1 binds a non-conformational epitope of E2. Patent WO 2007/143701 covers humanized murine antibody PA-29. This molecule binds the envelope glycoprotein of HCV genotypes 1 and 2, with IC50 values of 1 μg/ml or less. This claim was expanded in WO 2008/079890A1 to antibodies specifically targeting E1 and E2, or a complex of the two. WO 2007/143701 is similar, covering humanized and chimeric antibodies derived from hybridoma CL binding the same targets. Less common antibody targets include the E1 domain (patent WO 2007/111965) and the NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) activity, which inhibits viral replication [15]. Lastly, Bavituximab, the anti-phosphatidyl serine antibody with broad-range antiviral potential discussed above, is expected to enter clinical trials to prevent recurrence of HCV after liver transplantation.

Human Immunodeficieny Virus (HIV)

HIV is grouped in the retrovirus family and can result in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. According to United Nations AID/World Health Organization 2008 Epidemic update, 33 million people are currently infected with more than 6,800 people newly infected each day (http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/default.asp). HIV infection targets T lymphocytes expressing a CD4 cell surface glycoprotein by slowly depleting or impairing them functionally. The mechanism of HIV entry involves formation of a complex between the HIV envelope glycoproteins (ENVgp) gp120-gp41, a cell-surface receptor (CD4), and a cell-surface co-receptor (chemokine receptor CCR5 or CXCR4) [16]. To date the most widespread HIV treatment is a cocktail of reverse transcriptase and protease inhibitors. These have shown dramatic effects in clinical trials as well as significant toxicity and development of escape variants.

Blocking the gp120-receptor interaction

Most antibody therapeutics target the association between virus and cellular receptors, but few broadly neutralizing antibodies have been characterized. The primary vaccine target, gp120, is heavily covered with mannose residues, masking potentially neutralizing epitopes and allowing the virion to masquerade as a self-mannosylated molecule. A rare, potently neutralizing antibody, 2G12, has been identified which protects against viral challenge in vivo in animal models by binding terminal Man α1-2Man residues on gp120 [17]. More recently, human single-domain antibodies with long CDR3 loops have been identified which are able to reach recessed, conserved epitopes on the viral envelope glycoprotein. A VH domain, m36, targets a highly conserved region of gp120 [18]. The VH domain exhibits broad cross-reactivity with HIV-1 isolates, neutralizing with an activity that higher than the T-20 peptide fusion inhibitor. The m44 domain antibody targets gp-41, neutralizing most of the 22 HIV-1 primary isolates tested, including those from different clades [19]. TNX-355, in development by Tanox (patent WO 920930) is composed of antibodies directly binding the CD4 receptor. Phase II trials indicated an increase in T-cell count after antibody administration but TNX-355 will likely be used in combination with other anti-HIV drugs.

Blocking the gp120-co-receptor interaction

The mechanism for inhibition of the co-receptor is still not clearly understood, although the FDA approved the small molecule CCR5-blocking drug Selzentry (Pfizer) in 2007. Progenics has developed anti-CCR5 antibody Pro 140, a humanized version of the murine antibody PA14, which the FDA assigned fast track status. Synergy has been observed between PRO140 and inhibitors currently in clinical trials (e.g., Rantes, Pfizer). [20]. Patent WO 2007/014114 A2 describes an antibody cocktail (Pro140 and a second anti-CCR5 antibody), demonstrating their combined ability to reduce HIV-1 viral load in phase II clinical trials by suppression of viral replication. Anti-CCR5 antibody HGS004 is a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for CCR5, generated using Abgenix XenoMouse® technology, acquired by Human Genome Sciences. This antibody has been reported to inhibit CCR5-dependent entry of HIV-1 viruses into human cells, and showed antiviral activity in Phase I clinical trials, as well as tolerance in patients. Current work has shown that when incorporated with ENF (enfuvirtide, a fusion peptide) as one molecule, both contribute to anti-viral activity [21, 22]. These trials have demonstrated the potential for combined anti-CCR5-inhibitor treatments as therapeutic regimens, establishing the need for additional clinical exploration.

Additional antibodies being explored for anti-HIV use include antibodies binding the CXCR4 co-receptor, covered by patent WO 2008/060367. A slightly different neutralization mechanism is pursued by antibodies binding the α4 integrin, covered by WO 2008/140602 A2. Interactions between gp120 and integrin α4β7 aid in efficient cell-to-cell spreading of HIV-1 [23]; the humanized antibody described is used as an α4 integrin antagonist, thereby reducing HIV infectivity. Current studies are assessing the potential for the integrin-binding antibody Natalizumab (Tysabri™), currently marketed for multiple sclerosis, for inhibiting HIV spread.

Respiratory syncitial virus (RSV)

Approximately 3% of US infants are hospitalized with RSV, making it the most common cause of infant hospitalization. The success of high-titre anti-RSV immunglobulin (Respigam), approved in 1996, led to development of the first monoclonal antibody approved for infectious diseases, Synagis, in 1998. This humanized molecule is extremely successful commercially, reducing the percent of high-risk infants hospitalized (10.6% to 4.8%) and length of hospital stays by 50–60% [24]. The effect on high-risk infants not hospitalized has not been well-studied, nor has the viral titre been used as a clinical endpoint. Extensive engineering efforts have improved the antibody binding characteristics, with the goal of further improving clinical performance. A second generation antibody variant developed via phage display with 13 amino acid changes exhibits a 70-fold improved affinity (Kd = 34 pM) for the RSV viral F (fusion) protein and is currently in Phase III clinical trials [25, 26]. Interestingly, selection for antibody variants with an improved on-rate led to undesirable non-specific tissue binding and poor lung bioavailability, thus a 44-fold improved in vitro performance translated into only a 2-fold in vivo reduction in viral titres. Removal of some of the amino acid residues conferring higher affinity was able to resolve the non-specific binding problem, but underscores the idea that higher affinity binding is not always better. Antibody binding to the F protein is thought to block viral cell penetration and spreading via syncytial formation. Despite widespread use of the antibody in the US, emergence of antibody escape variants was not observed in a multi-center clinical trial [27]. Given the size of the anti-RSV market, it is not surprising that additional patents covering anti-RSV therapeutic antibodies have been filed, in particular, US patent 2007/0082002 A1 covering additional molecules binding the F protein and US 2007/0224204 A1 covering a combination therapy comprised of a specific antibody and an anti-inflammatory antibody (e.g., anti-IL-6). In addition, Symphogen is developing a recombinant polyclonal antibody preparation, Sym003, to target non-overlapping epitopes on both the RSV F and G proteins.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (CoV)

Three human coronaviruses are estimated to cause 15 – 30% of common colds and may also contribute to lower respiratory tract infections [28]. The SARS-CoV, a relatively new type of highly communicable human coronavirus, was identified as the cause of the 2002 outbreak which caused 8100 documented cases with a 9.5% fatality rate [29] and spread to 30 countries.

Recombinant parainfluenza virus expressing SARS-CoV structural proteins has demonstrated that the surface exposed spike protein is necessary and sufficient for the bulk of the neutralizing antibody response, yielding a titre in hamsters half that of the native SARS virus. Other structural proteins, either alone or in combination with the spike protein, provided minimal additional neutralizing response [30]. The spike protein includes a receptor binding domain which interacts with the cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. As a key neutralizing epitope has been mapped to amino acid residues 318-510 in the receptor-binding domain, the mechanism of neutralization is thought to be steric hindrance of the initial virus-receptor interaction. Supporting this, structural evidence has shown that neutralizing antibody 80R binds an epitope on the spike protein which overlaps with the receptor epitope [31]. Antibody-mediated treatments for SARS appear promising [32], as both the 80R ([33]; covered in patent WO 2007/044695 A2) and 201 antibodies ([34]; covered in US patent 2005/0069869 A1) reduce viral titres up to four orders of magnitude when administered prophylactically in a hamster model (for a detailed review, see [35]). Among circulating SARS strains, antibodies that neutralize spike proteins from human SARS isolates unexpectedly enhanced the infectivity of palm civet strains, indicating that development of antibody escape variants may be a concern [36, 37].

Not surprisingly, there is commercial and academic interest in developing therapeutic anti-SARS antibody preparations, most of which target the spike protein receptor binding domain. Patent: WO2007/044695 covers the production and therapeutic use of antibodies 11A and 256, which block viral-cellular adhesion by binding an S1 region between amino acids 472 and 480, and can be administered independently or as a cocktail with an 80R-like antibody. Similar antibodies are a reported in WO 2006/051091 A1, US 2006/0240551 and US 2008/0248043. The former describes a combination of two neutralizing human antibodies which block the spike protein-receptor interaction, under development by Crucell [38]. The first antibody, CR3014, neutralizes a standard SARS-CoV strain. Antibody escape variants containing a single amino acid change (P462L) were identified by growing virus strain HKU-39849 in the presence of neutralizing doses of CR3014. A human convalescent antibody phage library was then used to identify a novel antibody, CR3022, able to neutralize the P462L escape variant. The antibodies bind different epitopes on the receptor binding domain and display synergy in in vitro neutralization experiments. The latter patent, US 2008/0248043, demonstrated human antibodies and antigen-binding fragments which neutralize 200 times the tissue culture infections dose with an antibody concentration of 12.5 ug/mL.

Smallpox (variola)

Smallpox, caused by the variola virus, was declared eradicated in 1980 but is now considered a potential biological weapons threat. A large fraction of the world’s population has not been immunized against the virus, thus release of native or engineered variola could result in a major pandemic. Consequently, the United States and many European countries are in the process of stockpiling vaccine – sufficient to supply one dose per person. Moreover, a new vaccine based on cell-culture produced vaccinia virus (a close relative to variola) was approved in 2007 (ACAM2000; Acambis Inc) and is currently in production. Passive immunotherapy could be a critical component of an emergency smallpox response as vaccinia immunoglobulin remains the only recommended treatment.

The similarities between vaccinia and variola viruses have allowed for a broad range of studies identifying neutralizing epitopes. The H3L envelope protein has been identified as the immunodominant antigen in the live viral vaccine (US patent 7,393,533 B1) [39], while antibodies recognizing the exposed envelope protein B5 protein are thought to be responsible for most of the neutralizing activity present in immune sera [40]. Chimeric chimpanzee/human antibodies, covered by patents WO 2008/085551 and WO 2008/0112959, recognizing a conformational B5 epitope with sub-nanomolar affinities, are able to protect mice when administered prophylactically or two days after viral challenge. A similar set of antibodies recognizing the A33 protein, covered by patent WO 2007075915, were able to protect mice from the same challenge, but were not synergistic with the anti-B5 antibodies [41].

Commercially, Macrogenics is creating a cocktail of two neutralizing antibodies for post-exposure prophylaxis that are still in pre-clinical trials. Symphogen is also in development with Sym002, a smixture of 26 human recombinant anti-vaccinia virus antibodies (covered by patents WO 2006/007853 A2, US 2008/0069822). The results show that Sym002 has a higher neutralizing titre than the current immunoglobulin preparations, and that the mixture could potentially replace existing anti-vaccinia hyperimmune immunoglobulin treatments.

South American arenaviruses

In spite of a case fatality rate of 15–30%, no treatments beyond supportive care exist for four of the five viral hemorrhagic fevers caused by the family of South American arenaviruses: Guanarito, Machupo, Junín, Sabía and the newly identified Chapare [42]. Disease incidence is increasing as development in rural endemic areas results in more frequent contact between humans and rodent carriers. Moreover, due to their severe morbidity and mortality, and potential human-to-human transmission of Machupo virus, misuse of these NIAID Category A viruses poses a potential concern [43].

Preliminary evidence has demonstrated the success of convalescent immune sera in treating fever caused by Junín virus, but neurological effects occur in ~10% of patients and there are difficulties in maintaining a supply. Five murine hybridoma cell lines developed by immunization with Junin strain P3406 [44] were shown to bind the glycoprotein by whole virus Western blot and radioimmunoprecipitation assay, while immuno-fluorescence assay demonstrated the specificity of these antibodies for Junín versus heterologous arenaviruses. Four of the five antibodies were additionally capable of virus neutralization in vitro [44], suggesting the Junin glycoprotein1 (GP1) contains at least two immunogenic epitopes, one neutralizing and one non-neutralizing.

Greater detail regarding GP1 epitopes has been obtained for the Old World arenaviruses and may be predictive of those on South American arenaviruses. It is well-accepted that not only do immune sera protect against Old World Lassa viral infection [45], but that sera from the same geographical location as the patient (and thus presumably, strains with high amino acid sequence homology), are most effective [46, 47]. Both Lassa and LCMV GP1 have four major epitopes, A, B, C and D, two of which (A and D) are both conformational and neutralizing [48, 49]. Interestingly, antibodies recognizing the LCMV site GP1-A are broadly cross-reactive with four commonly used lab strains, while GP-1D neutralizing antibodies showed strain specificity correlating with amino acid residue T173, suggesting GP-1D is highly mutable. Polyclonal IgG raised in guinea pigs reacted predominantly with two of the four antigenic sites on LCMV GP1, primarily against the major neutralizing determinant, GP-1A [48]. Together, this evidence suggests that highly neutralizing GP1 epitopes may be conserved across some arenaviral serotypes; epitopes for which high affinity monoclonal antibodies may also be useful in treating South American viral hemorrhagic fevers [50].

West nile virus (WNV)

West Nile Virus originated in Uganda but has spread throughout the world, with 4,000 cases reported in the United States in 2006. Two potential treatments have been explored for WNV with encouraging results are antivirals combined with interferon-alpha2b and human anti-WNV immunglobulin (Omr-IgG-am™) [51]. Supporting the second approach, a key neutralizing epitope has been identified: analysis of antibody repertoires from three patients infected with WNV showed that 121 of 125 screened antibodies bound the viral envelope (E) protein. Competitive ELISA indicated that 47% of antibodies bound to domain II (primarily non-neutralizing), while 8% targeted domain III of the E protein. [52]. Two of these are potently neutralizing, able to protect mice fro lethal virus challenge at doses as low as 12.9 ug/kg body weight (covered by US patent 7,244,430 B2). Another antibody, identified by yeast display (E16), neutralized ten different strains in vitro and showed therapeutic efficacy in vivo, even when administered five days after infection [53]. Structural analysis revealed this strongly neutralizing epitope corresponds to the lateral ridge of E protein domain III [54]. Antibodies recognizing this epitope block a late step in cellular invasion, reducing the stoicheometric requirements for antibody neutralization [55]. Humanized versions of E16 (MGAWN1) have been developed, recently completing Phase I clinical trials with Macrogenics Inc. [53]. In earlier stages of development, US patent 2007/0042359 A1 covers a selection of neutralizing human antibodies identified by phage display with specificity for WNV EII and EIII domains, while patent US 2006/063463 covers optimization of West Nile Virus antibodies by light chain shuffling.

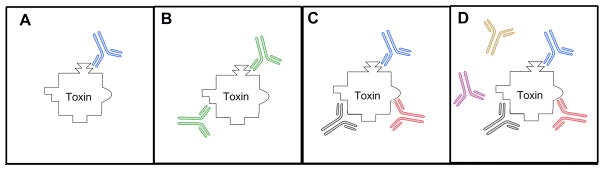

Anti-toxin immunotherapy

Bacterial toxins are perhaps the simplest targets for antibody therapeutics since, in general, no effector or accessory functions are required: merely an antibody with the ability to neutralize toxin activity. This can occur by competition with the cellular receptor for toxin binding (as is the case for anthrax toxin protective antigen) or, for catalytically active toxins, antibody binding can block substrate access to or function of the catalytic site (see Figure 2). For many toxins, the Fc domain does not appear to be required. For instance, Fab preparations lacking effector functions have been found to be equally effective as the complete IgG against staphyloccocal alpha-toxin [56], tetanus toxin [57], and diptheria toxin [58], with the advantage of eliminating side effects associated with the Fc (e.g. the activation of complement and allergic reactions).

Figure 2.

Toxin neutralizing antibodies: A. monoclonal antibody consisting of a single antibody binding a single unique epitope on the toxin, B. bi-specific antibody in which each arm is able to bind a different epitope on the toxin, C. oligoclonal antibodies consiting of a mixture of two or more monoclonal antibodies that each bind a single unique epitope on the toxin, D. polyclonal antibodies consisting of a mixture of several monoclonal antibodies that either bind or don’t bind to the toxin.

Bacillus anthracis

The bacterium B. anthracis is a spore forming, heat-resistant soil bacteria commonly infecting grazing animals with mortality rates of up to 80%. While vaccination and antibiotics are effective in early exposure, its use as a biological weapon in 2001 highlighted the need for late stage treatment options [43]. The rapid growth and proliferation of the bacteria is mainly due to the secretion of a tripartite toxin, consisting of the protective antigen (PA), the lethal factor (LF), and the edema factor (EF). Since both the catalytically active LF and EF are active only in the cellular cytosol, PA, which binds to the host cell and facilitates their translocation, has been the main focus of most anti-anthrax antibody research.

US Patent 6916474 covers the antibody fragments (scFv and scAb), the humanized CDR grafted antibody, the human antibody, and the mouse antibody 14B7 which successfully neutralizes the anthrax toxin prior to its interaction with the target cell by binding PA (see Figure 2) [59]. Affinity was improved through the use of affinity maturation [60] resulting in equilibrium binding constants between 140 – 21 pM, blocking toxin activity in vivo. The resulting heteropolymer drug Anthim™, administered via a single intramuscular or intravenous injection, is being developed by Elusys based upon this technology. Animal studies on both primates and rabbits, showed the drug to offer significant protection when administered 24 hrs post exposure to lethal infection. In 2006, a Phase I human safety study (NCT00138411) demonstrated it to be safe and well-tolerated with or without antibiotics. It is currently in Phase II clinical trials.

ABthrax™ (Raxibacumab) is another human monoclonal antibody also binding PA to prevent its adhesion to cell surfaces discovered in collaboration with Cambridge Antibody Technology. This is based upon the unique “recall” method outlined in US patent 2008/0081042 previously reviewed as US patent 2006/0246079 [61]. Human Genome Sciences is developing the drug under contract with the US Government since 2006. Animal studies with monkeys and rabbits exposed by inhalation to lethal infection with a single intravenous dose of ABthrax showed significant protection even after showing clinical signs of the disease. In Phase I clinical trials, two human safety studies likewise demonstrated it to be safe and well-tolerated in adults with or without antibiotics with either an intramuscular or an intravenous dose [62].

Clostridium botulinum

Like B. anthracis, the bacteria C. botulinum is also an anaerobic spore forming soil bacteria. It produces seven similar neurotoxins, BoNT/A-G, which penetrate motor neurons at the neuro-muscular junction and block acetylcholine release, thereby inducing muscle paralysis. Although approved for medical and cosmetic uses, it is ranked in the highest category of biological threats, Category A [63].

US patent application 2006/0177881 uses mice immunized with the non-toxic BoNT/A to generate BoNT/A and BoNT/A-HC (heavy chain binding fragment) neutralizing antibodies, identified via hybridoma and phage library screening. The unique neutralizing epitope bound by these antibodies, which do not cross-protection with BoNT/B-G, was then determined using overlapping peptides of BoNT/A-Hc. Three distinct, neutralizing epitopes were identified, two linear and one conformational [64].

Building on the idea that multiple independent neutralizing epitopes are present on BoNT/A, US patent application 2008/0124328 (a re-application of US patent application 2004/0175385) covers a cocktail of three unique BoNT/A neutralizing antibodies. These were isolated from an antibody phage-library and recognize non-overlapping epitopes [65, 66]. The combination of all three antibodies neutralized toxin with a potentcy 90 times greater than the high titre human immuneglobulin which is standard clinical treatment. The patent reapplication describes cross-reactive or bi-specific antibodies binding at least two different BoNT subtypes in an oligoclonal therapeutic cocktail. Through the utilization of yeast display and co-selection, an antibody with high affinity for sub-type A1 (136 pM) and low affinity for sub-type A2 (109 nM) was engineered to interact with both subunits with similar affinity, ~100 pM [67]. Structural co-crystallization data demonstrated that engineering introduced new structural interactions between the antibody heavy chain CDR1 and toxin subtype A2 which did not compromise the interactions with subtype A1. A single antibody with broad sub-type specificity would be particularly useful in the clinic, where it could be administered without the need to first identify the infecting subtype.

Clostridium difficile

A related bacteria, C. difficile, readily colonizes the colon in the absence of natural flora, usually as a result of antibiotic use. The bacteria secretes two exotoxins, A and B, which have multiple functional domains and cause extreme cases of diarrhea [68]. Relapse rates have increased in recent years due to increased bacterial virulence and antibiotic resistance [69].

US patent application 2006/0029608 covers both active and passive immunization to the exotoxins of C. difficile through either exotoxin injection or neutralizing polyclonal human immunoglobulins. These immunoglobulins are produced through the active immunization with toxin and subsequent isolation of high titre immune globulin. The use of this material for passive immunization in lieu of, or in addition to, antibiotics successfully inactivated the exotoxins while allowing normal colon flora growth. The normal flora out competes C. difficile, thereby preventing relapse while reduced antibiotic use hinders development of resistant strains.

US patent application 2005/0287150 utilizes transgenic mice carrying human immunoglobulin genes to produce neutralizing human monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies both toxins. Antibodies for either toxin effectively protect from the disease including the side-effect of diarrhea and also future relapse. Of the three anti-toxin A and four anti-toxin B antibodies characterized, a combination treatment of CDA1 (anti-A) and MDX-1388 (anti-B) protected hamsters synergistically in a lethal challenge model. Two days after challenge, 5% of untreated animals were alive versus 8% MDX-1388 treated, 55% CDA1-treated and 94% animals treated with the antibody cocktail [70]. Medarex is developing this combination therapy and are currently in Phase II clinical trials.

Bordetella pertussis

In spite of vaccine availability for the past five decades, whooping cough remains a childhood scourge with no available therapy for established disease. Caused by the Bordetella pertussis bacterium, whooping cough is mediated by over twenty virulence factors, none of which provides a clear serological correlate of protection. Anti-pertussis toxin (PT) antibodies may be effective in ameliorating disease, a belief supported by three lines of evidence: (i) reduced virulence of bacteria lacking PT genes; (ii) demonstrated efficacy of the acellular pertussis vaccines (comprised of pertussis toxin and 0–4 additional virulence factors); and (iii) passive immunotherapy studies which have demonstrated protection and even reversal of disease post-infection.

A specific concentration of serum anti-PT antibodies conferring protection has not been determined, but many reports suggest this may track with recovery. In a prospective trial of 94 women who developed culture-confirmed pertussis, 38 patients showed long-term maintenance of high PT anti-toxin levels [71]. Furthermore, hyperimmune human anti-sera isolated from vaccinated volunteers has shown promise as a treatment. One human clinical trial observed a reduction in the number of whoops in human infants from 20.6 days in children receiving the placebo to 8.7 for those receiving high-titre immunoglobulin [72]. A more recent preparation, P-IGIV by Mass. State Dept Health also showed benefits but is no longer available due to production issues. In the murine aerosol model, P-IGIV treatment prior to infection conferred a dose-dependent decrease in mortality, lymphocytosis and weight loss. Mice with established infection showed a 90% survival rate when given P-IGIV versus 0% for mock-treated animals [73]. Phase I clinical trials of 26 children with confirmed pertussis saw an improvement in lymphocytosis and coughing within 72 hours of P-IGIV infusion [74]. Phase III clinical trials were prematurely terminated due to the expiration of the P-IGIV and unavailability of additional anti-sera. The study recruited 25 infants, a number insufficient to observe a significant difference in the symptoms of treated versus untreated patients [75].

Human or humanized antibodies that block the action of PT represent a potential therapeutic for the specific treatment of whooping cough in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. Numerous murine monoclonal antibodies have been produced and characterized at least preliminarily [76–83], but certain key epitopes appear to be weakly immunogenic. In one study [84] of ten anti-S1 monoclonal antibodies, only one displayed potent neutralizing activity in vivo in the aerosol and intra-cerebral challenge models although all showed high anti-catalytic activity in vitro. This antibody, 1B7, has been extensively characterized in the mouse model, alone and in combination with other neutralizing antibodies, in particular 11E6, which blocks association of PT with the cellular receptors. Each antibody is effective at blocking toxin function independently, but the combination of the two shows higher specific activity than a polyclonal anti-PT preparation when administered up to seven days after infection onset in a mouse model. Similar antibody cocktails may form the basis of a specific therapeutic for whooping cough.

Shiga toxin producing E. coli

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) infect humans through the ingestion of food or water contaminated by human or animal effluents. The disease is characterized by abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea and can lead to hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) [85]. Two exotoxins, Shiga toxin 1 and 2 (Stx1 and Stx2), are the etiological causes of infection with Stx2 being the primary virulence factor for HUS [86]. Similar to cholera and pertussis toxins, they are AB5 toxins comprised of an enzymatically active A subunit, responsible for inactivating 60S ribosomes and blocking protein synthesis and a pentameric B subunit responsible for cellular binding and internalization.

US patent application 2007/0160607 covers neutralizing humanized and chimeric antibodies 13C4 and 11E10 for Stx1 and Stx2, respectively. Passive immunization with murine 11E10 during the progression of HUS not only prevents the lethal effects of Stx2 but also allows for full recovery to normal renal function in mice [87]. A phase I dose escalation of the chimeric mouse-human IgG1 antibody in adult volunteers proved to be well-tolerated although saturable elimination was observed [88]. US patent application 2007/0292426 covers the 13C4 antibody including monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, in addition to antibody fragments and polypeptides, recognizing the same conformational epitope on Stx1. This antibody neutralizes Stx1 activity by competing with the cellular receptor for binding to the same or overlapping epitope on the B subunit. While 13C4 does not bind to the Stx2 B subunit, it may be possible to modify an existing antibody for multispecificity, as has been achieved for BoNT/A, described above [89]. Similarly, US patent application 2008/0107651 focuses on human or chimeric antibodies, mAb cocktails, or monospecific polyclonal antibodies that bind Stx1 and Stx2. These antibodies are produced using either transgenic mice to develop fully human antibodies [90] or the immortalization of mammalian spleen cells to develop chimeric antibodies. The fully human antibodies for Stx1 and Stx2 have been shown to be effective both in vitro and in vivo in a mouse and piglet model of HUS, respectively, while being safe, longing lasting, and better effectors. Of 40 infected piglets receiving antibody treatment, 85% survived, versus only 2.5% of placebo-treated animals [91–93]. Medarek (GenPharm International) is developing this technology, currently in clinical trials.

Anti-bacterial and anti-fungal immunotherapy

Several approaches to treating infection involve antibodies that directly bind surface-exposed molecules on whole bacterial or fungal cells. These antibodies can act by (1) recruiting immune system components to eliminate the pathogen (e.g., complement, ADCC); (2) blocking cell-associated pathogenic mechanisms, i.e., type III secretion of virulence factors; and (3) directly killing pathogens by targeted delivery of radionuclides or other toxic drugs (a direct extension of established anti-cancer therapies; see Figure 1, [94]). These approaches are less developed than those for anti-viral or anti-toxin therapy in that none have been approved for use and several promising candidates, Aurograb and Altastaph (Veronate?), reached Phase III trials, only to miss their efficacy targets.

Staphyloccocus aureus

S. aureus is one of the most troubling modern diseases, for three reasons: (1) antibiotic resistance is rampant, with over 50% termed “methicillin resistant Staph aureus” or MRSA; (2) not only is it one of the most common hospital-acquired infections, different strains have emerged from community settings; (3) efforts to develop vaccines and immune sera have been very disappointing [95, 96]. Infants with very low birth weights (<1500 g; <32 weeks gestation) are at a particular risk for nosocomial bacterial infection, as they have not benefited from trans-placental transfer of maternal antibodies; 75% of these infections are caused by S. aureus, thus VLBW infants are the primary target of anti-S. aureus and anti-MRSA therapies. Altastaph® is a vaccine-induced hyperimmune polyclonal antibody with specificity for S. aureus serotype 5 and 8, developed by NABI, covered under US patent 2006/0153857 A1. In spite of reaching target serum antibody levels, no decrease in S. aureus infection rates was observed in treatment groups in two clinical trials [97, 98]. A second anti-S. aureus human immune sera was prepared by first screening donors for high titres against MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesion matrix molecules), named Veronate® (INH-A21) and marketed by Inhibitex (US patent 6692739). Phase II trials appeared promising at the highest antibody dose, but a Phase III trials did not observe any effect of antibody treatment in reducing the frequency of S, aureus or Candida infections [99]. One explanation for these disappointing results is that control of S. aureus requires humoural and cellular and phagocytic responses; the immune system of a VLBW pre-mature infant may not adequately provide these components. Aurograb, developed by NeuTec, is an antibody binding the immunodominant ABC transporter in MRSA [100], blocks the multi-drug efflux pump allowing antibiotics to retain effectivity. Additional molecules now under development include a humanized monoclonal antibody, Aurexis® (Inhibitex, US patent 6979446), recognizing clumping factor A [101] and Pagibaximab® (BYSX-A110, US patent 2008/0019976 A1), a chimeric antibody binding lipoteichoic acid present in the membrane of gram-positive bacteria.

Candida albicans

Systemic fungal infections are an increasing health concern, especially for immunocompromised patients who exhibit mortality rates of 10–70% for these infections caused primarily by four Candida strains. Anti-fungal treatments, such as amphotericin B, are toxic to the patient and no longer effective against all fungal strains [102], spurring efforts to develop antibody therapeutics. This has been pursued along three distinct lines. Debate over relative importance of antibody-mediated versus innate or cell-mediated immunity in defense against Candidiasis is reflected in the fact that none of the approaches outlined below rely heavily on effecter functions.

Heteropolymers. US patent 2006/0263792 A1 reports the use of heteropolymer technology to develop a potent anti-fungal agent. This technology, developed by Elusys (Gaithersberg, MB), covalently couples a Candida-specific monoclonal antibody to an antibody specific for the CR1 protein on red blood cells. The first antibody binds a fungal cell surface antigen; the second immobilizes the complex on a red blood cell in a complement-independent manner. Moreover, when the red blood cell traverses the liver, the immune complex is recognized by macrophages and the antibody-pathogen complex phagocytosed [103]. Doses as low as 4 ug of Candida-specific heteropolymer completely protected infected mice over a 28-day study, while mock-treated animals succumbed in less than three days.

Radio-immunotherapy. A second approach is the use of specific, non-neutralizing antibodies to deliver toxic radionuclides to the pathogen [94]. A direct extension of treatments developed for cancer, strategies for coupling radionuclides are well-developed and the mechanism of cell killing well-understood. Described in US patent 2004/0115203, mAb 18B7, an antibody specific for Cryptoccocus neoformans with no anti-fungal activity, was coupled to 213Bi and shown to reduce fungal cell viability by at least two logs in vitro and resulted in 60% survival rate 80 days after lethal infection while all mock-treated mice succumbed by day 35 [104]. Cell killing was subsequently shown to be primarily a result of “direct hit” – only fungal cells directly bound by radio-labeled antibody were efficiently killed, neighboring cells were less affected. The use of armed antibodies relieves the pressure to identify key neutralizing epitopes – while antibody isotype was also found to play a role, the main requirement is that the antibody bind specifically and tightly to the pathogen of interest.

ScFv antibody. US patent 2008/0095778 and WO 01/76627 describes a bacterially produced scFv antibody recovered the cDNA of from patients surviving systemic Candidiasis, recognizing the essential molecular chaperone hsp90. Marketed since 2005 as Mycograb® (NeuTec), this antibody is effective solely by neutralizing hsp90, conferring response rates of 84% for treated and 48% for placebo controls by day ten when administered in conjunction with amphotericin B [105].

Novel antibody targets

Due to the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance after introduction of a new antibiotic, a current theme in anti-infective development is blockade of virulence factors not directly related to bacterial survival. The logic is that such a strategy will spare commensal bacteria, apply minimal pressure for evolution of resistance and yet still limit disease. Novel approaches that could be developed for a wide range of bacterial pathogens include:

Antibodies specific for quorum sensing molecules. Individual bacteria secrete small molecules termed “auto-inducers” (AI), including N-acyl homo-serine lactones (gram-negative bacteria) and oligo-peptides (gram-positive bacteria), at a constant, low level as a means of detecting the local concentration of bacteria. Upon reaching a threshold AI concentration – implying the presence of sufficient numbers of bacteria to mount a successful infection – expression of virulence factors is initiated including elastases and toxins. In S. aureus, these genes are under the control of a single global regulator, the agr locus. Previous work has focused on development of small molecules able to compete with the AI peptide for receptor binding and inhibit virulence gene expression; US patent 2006/0165704 describes a radically different approach, the development and use of high affinity antibodies binding AI to prevent transition of bacteria to a pathogenic form. In particular, monoclonal antibody AP4-24H11 was shown to sequester auto-inducing peptide-4 produced by S. aureus strain RN4850 and completely protect mice from lethal bacterial challenge when administered prohpylactically [106, 107].

Antibodies binding type III secretion components. Many gram-negative pathogens express a complex protein structure resembling a molecular syringe, capable of binding a host cell membrane and injecting toxins directly into host the cytosol. Antibodies binding to the terminal V protein, thus preventing association with the host cell membrane, have been shown to be effective in limiting disease in animal models for Yersinia species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [108, 109] and Aeromonas salmonicida (US patent 7232569). US patent 2006/0093609 discloses successful post-exposure treatment of the plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, using a combination of two anti-type III secretion antibodies, synergistically recognizing the V and F1 antigens. Interestingly, the mechanism appears to be simple steric hindrance of LcrV/PcrV binding to a cellular receptor, as Fab [110] and F(ab′)2 [111] fragments showed similar effectivity in preventing shock and death in animal models as the full-length IgG.

Multi-drug efflux pumps. One mechanism of bacterial antibiotic resistance is expression of multi-drug efflux pumps – before an antibiotic is able to exert its effect inside a cell, it is physically transported outside of the cell. A number of species-specific efflux pumps have been identified, along with antibodies blocking their function, as reported in US patent 2007/0202116 for Aurograb, which binds an immunodominant ABC transporter in MRSA [100]. The idea here is a dual therapy: an antibody to inactivate the pump is administered simultaneously with an antibiotic that is now able to reach its intracellular target. This idea has been used previously with limited success for small molecule pump inhibitors, but the large binding surface area of an antibody may limit generation of escape variants. A potentially general approach, similar antibodies specific for Clostridium difficile and Enterococcus drug efflux pumps were reported in US patent 2008/0038266.

Emerging technologies

In particular, we anticipate the following areas to play key roles in anti-infective patents in the coming years, Other ideas, not discussed in great deal here include:

Antibodies with broad serotype specificity The use of a single therapeutic to treat disease caused by multiple sertoypes, akin to broad spectrum antibiotics, As discussed above, this can be achieved through recognition of a conserved epitope, as has been observed for SARS and influenza viruses [10, 37, 112] or engineering, as for BoNT/A1 and 2 subtypes [113].

Antibody standardization. Continued standardization of antibody amino acid sequence to further stream-line production, regulatory approval and prediction of immunogenicity and For instance, many antibodies produced by Genetech utilize the same human light and heavy chain framework sequences The family of antibodies under development by an individual company already standardization [114] reported in US patent US 2007/0237764 A1.

Non-antibody scaffolds with unique binding characteristics. These include single-domain antibodies, with very long CDR loops, able to reach hidden conserved epitopes not accessible to traditional antibody binding sites [18] (as well as non-antibody binding motifs which exhibit remarkable stability and high level bacterial expression, such as designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) [115]

Revolutionary approaches For instance, the use of soluble, high affinity, engineered T cell receptors (TCR) or antibody-like TCRs [116] to specifically eradicate virally infected cells by virtue of the viral peptides displayed on surface-exposed major histocompatibility complex or for superantigen neutralization [117, 118].

Neutralizing antibody cocktails

Cocktails of high-affinity, human or humanized versions of antibodies binding multiple neutralizing epitopes can be even more effective than hyperimmune sera due to higher specific activity. It has been shown that anti-toxin protection correlates with dose and affinity in animal models [59]. Furthermore, as discussed above, work with monoclonal antibodies has shown that the potency of the polyclonal humoral immune response can be deconvoluted to a few monoclonal antibodies binding non-overlapping neutralizing epitopes, the ”protective immunome” [65]. For instance, two anti-tetanus toxin antibodies provided similar protection as a polyclonal preparation at >100-fold lower dose (0.7 mg versus 100 mgs) [119]. Similar studies with botulinum toxin showed that while no single mAb significantly neutralized toxin, a combination of three antibodies neutralized 450,000 50% lethal doses of BoNT/A, a potency 90 times greater than human hyperimmune globulin [65]. Antibody cocktails are under development for a number of indications including rabies (Crucell) and HIV.

A particularly elegant approach is the development of bi-specific antibodies: one stable cell line can produce an antibody able to simultaneously bind two unique targets. US patent 2007/0054362, assigned to Crucell Holland, addresses some of the issues related to cell line generation. They produce a stable cell line expressing a single antibody light chain (LC) and two distinct antibody heavy chains (HC1, HC2). Three unique antibody proteins are produced: a mono-specific antibody comprised of two LC and two HC1 polypeptides (~25% of the total protein purified); a second mono-specific antibody comprised of two LCs and two HC2 polypeptides (~25%); and a single bi-specific antibody comprised of two LCs, a single HC1 and a single HC2 polypeptide (~50%). In this way, antibodies recognizing, for instance, two related antigenic proteins (e.g., two serotype of botulinum toxin or viral strains), can be produced and administered simultaneously, without the need to diagnose which serotype is responsible for infection. Potential problems include the ratio of HC1 to HC2 expression, a variable which can change as the cells grow and influences the ratio of unique antibodies produced.

Taking this idea a step further, several groups are pursuing the idea of recombinant polyclonal antibodies (rpAb). This approach aims to combine the attributes of antibodies, which are highly purified preparations with well-defined binding and biophysical characteristics, with polyclonal immune sera, which contains antibodies binding a diverse set of pathogen-specific epitopes. The FDA-approval route is not clear for oligoclonal treatments – typically, combination therapies require safety testing of the individual components, as well as the combination -- and is even less clear for these extremely diverse antibody preparations. A key question is how to produce consistent lots when the cell bank is a mixture of individual cell lines, expressing different individual antibodies and growing at different rates; proposed methods are covered by US patents 2008/0206236 and 2008/0131882 [120] [121]. Regardless, the first recombinant polyclonal antibody (rpAb), SYM 001 under development by Symphogen, entered clinical trials in March 2007 for treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic pupura and hemolytic disease in newborns [121]. Additional rpAb are under development by Symphogen for smallpox, RSV and two undisclosed infectious disease targets [122].

Engineering of the constant region

The antibody constant region (Fc) is largely responsible for its long circulating half-life in vivo as well as mediating interactions with the immune system [123]. PH-dependent binding to the neonatal Fc receptor FcRn results in recirculation as opposed to degradation of internalized antibodies; point mutations in the heavy chain constant region can be used to modulate the affinity for FcRn and thus in vivo antibody concentrations and dosing regimens, as described in US patents 2007/0122403 A1, 2007/0135620 and 7,365,168 [124].

The mechanisms by which an antibody neutralizes pathogenic material can be diverse, including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), opsonization, and steric hindrance of ligand activity, almost all of which require the antibody Fc region to interact with cellular receptors [4, 125, 126]. For instance, ADCC depends upon the Fc interaction with the activating FcγRIIIa receptor, present on natural killer cells and other leukocytes. Increasing the affinity and selectivity of this interaction through three Fc amino acid substitutions increased ADCC by two orders of magnitude in vitro [127]. This and related ideas are covered by a series of patents applied for by Xencor, including US patent 2008/0242845. Alternatively, ADCC can be modified by tuning the Fc glycosylation patterns. Typically, two oligosaccharide chains are interposed between two CH2 chains in the Fc, covalently attached to Asn 297. Increasing the amount of bisecting N-acetyl glucosamine while reducing fucosylation increases ADCC, as covered by US patent 2008/0280322.

Computational methods for epitope mapping

The difficulties inherent in performing experiments, such as mutagenesis and co-crystallization, to identify neutralizing epitopes with molecular precision have led to an explosion in computational methods to predict antibody binding sites. The best of these combine bioinformatic and biophysical methods to predict a family of potential binding sites and are thus used to guide experimental efforts. However, the area has made tremendous advances in the past ten years, in the future, experiments may be necessary only to confirm a prediction [128].

US patent application 2007/0005262 covers a hybrid experimental-computational approach for identification of linear and conformational epitopes. First, a peptide phage display library is screened to isolate peptides with affinity for the antibody. Second, the Mapitope algorithm uses the peptide sequence in conjunction with the antigen crystal structure to determine one-to-three possible epitopes, which are then tested experimentally. The program has successfully predicted two linear epitopes in addition to the discontinuous epitope of the Her-2 receptor, all of which had previously determined co-crystal structures [129]. Another hybrid approach, covered by US patent 2007/0117126, is “shotgun scanning mutagenesis.” Here, a library of individual alanine mutations are introduced into a phage displayed antibody, which is then selected for members retaining the ability to bind antigen [130]. Extensive DNA sequencing and statistical analysis are used to identify amino acid residues playing functional roles in the epitope. The advantages of this approach are that it bypasses protein purification and biophysical analysis while rapidly analyzing multiple side chains simultaneously.

RosettaDock is a fully computational program used for determining binding epitopes on both the antibody and the antigen. Structures for each individual binding partner are submitted into the program which then uses a Monte-Carlo rigid-body search and energy minimization scheme to predict the ten most energetically favored docking models [131, 132]. The program has a success rate of 60% for docking unbound components within 10 Å of an experimentally determined complex, as it is limited by its assumption of a rigid protein backbone and a maximum protein size submission of only 88 kD [133]. Computational alanine scanning mutagenesis determines which residues are most likely to be energetically important in a binding interface. Each amino acid at the interface is computationally changed to alanine and the resultant ΔΔG calculated, resulting in a list of significantly destabilizing residues [134]. These residues can be confirmed experimentally via point mutagenesis. However, mutations of key binding residues sometimes has no effect on affinity [135] and while that of a non-binding residues can have large effects on affinity [136], indicating that this tool is best used for suspected epitope regions.

Current and future developments

Antibodies have a long history as anti-infectives; in particular, polyclonal immune sera has demonstrated clear benefits in terms of reducing disease morbidity and mortality against a number of viral and bacterial diseases, remaining the standard of care in some cases. Increasing antibiotic resistance, along with the emergence and re-emergence of a number of diseases underscores the need for rapid development of specific therapeutics. Unfortunately, efforts to develop recombinant monoclonal antibodies that recapitulate polyclonal anti-sera has not been straightforward, largely due to challenges in identifying appropriate target epitopes and interactions with the rest of the immune system (clearly illustrated in the cases of HIV and S. aureus bacteria). In the cases of RSV and anthrax, key neutralizing epitopes have been identified, resulting in a remarkably successful drug in the first case and several promising candidates in the second. As our understanding of the detailed pathogenesis and role played by humoural immunity in individual diseases improves, scientists will be positioned to identify key neutralizing epitopes and effector functions critical to successful immunotherapy design.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from NIH grant AI066239, Packard Foundation 2005-29098 and start-up funding from the University of Texas at Austin.

References

- 1.Casadevall A, Dadachova E, Pirofski LA. Passive antibody therapy for infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(9):695–703. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeitlin L, Cone RA, Moench TR, Whaley KJ. Preventing infectious disease with passive immunization. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(6):701–8. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy B. Antivirals - an increasingly healthy investment. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25(12):1390–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt1207-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marasco WA, Sui J. The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1421–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castilla V, Contigiani M, Mersich SE. Inhibition of cell fusion in junin virus-infected cells by sera from argentine hemorrhagic fever patients. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(4):286–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldridge JR, Buchmeier MJ. Mechanisms of antibody-mediated protection against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection: Mother-to-baby transfer of humoral protection. J Virol. 1992;66(7):4252–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4252-4257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares MM, King SW, Thorpe PE. Targeting inside-out phosphatidylserine as a therapeutic strategy for viral diseases. Nat Med. 2008;14(12):1357–62. doi: 10.1038/nm.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sia IG, Patel R. New strategies for prevention and therapy of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(1):83–121. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.83-121.2000. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borucki MJ, Spritzler J, Asmuth DM, et al. A phase ii, double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled evaluation of a human monoclonal anti-cytomegalovirus antibody (msl-109) in combination with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone in the treatment of aids patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Antiviral Res. 2004;64(2):103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against h5n1 and h1n1 recovered from human igm+ memory b cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(12):e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickson RC, Terrault NA, Ishitani M, et al. Protective antibody levels and dose requirements for iv 5% nabi hepatitis b immune globulin combined with lamivudine in liver transplantation for hepatitis b-induced end stage liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(1):124–33. doi: 10.1002/lt.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu XN, Screaton GR. Mhc/peptide tetramer-based studies of t cell function. J Immunol Methods. 2002;268(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormier EG, Tsamis F, Kajumo F, Durso RJ, Gardner JP, Dragic T. Cd81 is an entry coreceptor for hepatitis c virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(19):7270–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402253101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callens N, Ciczora Y, Bartosch B, et al. Basic residues in hypervariable region 1 of hepatitis c virus envelope glycoprotein e2 contribute to virus entry. J Virol. 2005;79(24):15331–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15331-15341.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikonov A, Juronen E, Ustav M. Functional characterization of fingers subdomain-specific monoclonal antibodies inhibiting the hepatitis c virus rna-dependent rna polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(35):24089–102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803422200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray N, Doms RW. Hiv-1 coreceptors and their inhibitors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;303:97–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-33397-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, et al. Hiv vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(3):233–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W, Zhu Z, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS. Human domain antibodies to conserved sterically restricted regions on gp120 as exceptionally potent cross-reactive hiv-1 neutralizers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(44):17121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805297105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang MY, Vu BK, Choudhary A, et al. Cross-reactive human immunodeficiency virus type 1-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that recognizes a novel conformational epitope on gp41 and lacks reactivity against self-antigens. J Virol. 2008;82(14):6869–79. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00033-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murga JD, Franti M, Pevear DC, Maddon PJ, Olson WC. Potent antiviral synergy between monoclonal antibody and small-molecule ccr5 inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(10):3289–96. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00699-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji C, Zhang J, Dioszegi M, et al. Ccr5 small-molecule antagonists and monoclonal antibodies exert potent synergistic antiviral effects by cobinding to the receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(1):18–28. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopetzki E, Jekle A, Ji C, et al. Closing two doors of viral entry: Intramolecular combination of a coreceptor- and fusion inhibitor of hiv-1. Virol J. 2008;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arthos J, Cicala C, Martinelli E, et al. Hiv-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral t cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(3):301–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeVincenzo J. Passive antibody prophylaxis for rsv. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(1):69–70. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318160921e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu H, Pfarr DS, Tang Y, et al. Ultra-potent antibodies against respiratory syncytial virus: Effects of binding kinetics and binding valence on viral neutralization. J Mol Biol. 2005;350(1):126–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu H, Pfarr DS, Johnson S, et al. Development of motavizumab, an ultra-potent antibody for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in the upper and lower respiratory tract. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(3):652–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeVincenzo JP, Hall CB, Kimberlin DW, et al. Surveillance of clinical isolates of respiratory syncytial virus for palivizumab (synagis)-resistant mutants. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(5):975–8. doi: 10.1086/423213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau SK, Che XY, Woo PC, et al. Sars coronavirus detection methods. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(7):1108–11. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Booth TF, Kournikakis B, Bastien N, et al. Detection of airborne severe acute respiratory syndrome (sars) coronavirus and environmental contamination in sars outbreak units. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1472–7. doi: 10.1086/429634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchholz UJ, Bukreyev A, Yang L, et al. Contributions of the structural proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus to protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(26):9804–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang WC, Lin Y, Santelli E, et al. Structural basis of neutralization by a human anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome spike protein antibody, 80r. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(45):34610–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603275200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ter Meulen J, Bakker AB, van den Brink EN, et al. Human monoclonal antibody as prophylaxis for sars coronavirus infection in ferrets. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2139–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sui J, Li W, Roberts A, et al. Evaluation of human monoclonal antibody 80r for immunoprophylaxis of severe acute respiratory syndrome by an animal study, epitope mapping, and analysis of spike variants. J Virol. 2005;79(10):5900–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.5900-5906.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts A, Thomas WD, Guarner J, et al. Therapy with a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody reduces disease severity and viral burden in golden syrian hamsters. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):685–92. doi: 10.1086/500143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Ohnishi K, Takemori T. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (sars) coronavirus: Application of monoclonal antibodies and development of an effective vaccine. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16(2):117–31. doi: 10.1002/rmv.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang ZY, Werner HC, Kong WP, et al. Evasion of antibody neutralization in emerging severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sui J, Aird DR, Tamin A, et al. Broadening of neutralization activity to directly block a dominant antibody-driven sars-coronavirus evolution pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(11):e1000197. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ter Meulen J, van den Brink EN, Poon LL, et al. Human monoclonal antibody combination against sars coronavirus: Synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]