Abstract

Purpose. The objective was to compare the salivary protein profiles of saliva specimens from individuals diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast (IDC) with and without lymph node involvement. Methods. Three pooled saliva specimens from women were analyzed. One pooled specimen was from healthy women; another was from women diagnosed with Stage IIa IDC and a specimen from women diagnosed with Stage IIb. The pooled samples were trypsinized and the peptide digests labeled with the appropriate iTRAQ reagent. Labeled peptides from each of the digests were combined and analyzed by reverse phase capillary chromatography on an LC-MS/MS mass spectrometer. Results. The results yielded approximately 174 differentially expressed proteins in the saliva specimens. There were 55 proteins that were common to both cancer stages in comparison to each other and healthy controls while there were 20 proteins unique to Stage IIa and 28 proteins that were unique to Stage IIb.

1. Introduction

Clinicopathologic factors such as histologic type, tumor size, tumor grade, HER-2/neu over-expression, hormone receptor status, and lymph node involvement are recognized as having prognostic use in breast cancer management [1–4]. Collectively assessed, axillary lymph node metastasis is the most important prognostic factor predicting breast cancer patient survival [5–7]. Currently, the best predictor of axillary lymph node metastasis is the presence or absence of metastasis in the sentinel lymph node.

Current methodologies for this assessment are limited to axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel lymph node biopsy; however, these procedures are not without risks. For example, level I and level II axillary lymph node dissection can be associated with upper extremity lymph edema, wound complications, or nerve injury in a significant proportion of patients. Although sentinel lymph node biopsy is far less morbid than axillary lymph node dissection, it is not without risks or morbidity [8, 9]. Sentinel lymph node biopsy, despite its low but measurable false negative rate, provides no information about the presence of additional nonsentinel lymph node metastasis, which may occur in 40% to 70% of cases [10–12]. As a consequence, newer, more accurate, and less invasive means of predicting axillary lymph node metastasis would greatly improve breast cancer patient management and quality of life.

Morphological mimicry among human malignancies is a well-known histopathological phenomenon [11]. This is especially true in the case of the neoplastic ductal tissues of the breast and the salivary glands where immunostaining revealed the presence of Her2/neu (c-erbB-2), progesterone receptor, androgen receptor, and GCDFP-15 among these diseased tissues [11–14]. These studies suggest that similar molecular pathway dysfunctions may also be common within both tissues types [15].

Consequently, research has been performed concerning the presence of cancer related proteins and protein alterations in the secretory by products of these tissues, that is, saliva and nipple aspirate fluid (NAF) [16, 17]. Single analyte ELISA-based analyses yielded the presence of soluble Her2/neu protein in both saliva and NAF; Her2/neu concentrations were found to be elevated in both fluids secondary to the presence of carcinoma of the breast [16, 17]. Remarkably, Her2/neu protein concentrations were also elevated in the contralateral healthy breast within the same subject. Collectively, this line of research suggests that cancer-related cellular signaling may affect healthy exocrine tissues and result in alterations of their secretory by products. Likewise, EGFR and TNF-α were also found to be present in both fluids and altered in the presence of malignant breast disease [18]. Adding further support to this concept, both saliva and NAF were analyzed using mass spectrometry [19–21]. These fluid analyses yielded striking similarities with respect to their protein profile in health and were altered in the presence of neoplastic disease [19, 21].

Capitalizing on the potential of this possible relationship, significant salivary protein profile comparisons and alterations were reported in early stage breast cancer [21]. As a consequence, the purpose of this paper is to report saliva alterations secondary to late stage IDC with a focus concerning lymph node and nonlymph node involvement among the IDC cohorts.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The investigators protein profiled three pooled, stimulated whole saliva specimens. One specimen consisted of pooled saliva from 10 healthy subjects, another specimen was a pooled saliva specimen from 10 Stage IIa (T2N0M0) invasive ductal carcinoma patients (IDC), and the third pooled specimen was from 10 subjects diagnosed with Stage IIb (T2N1M0) invasive ductal carcinoma [22]. The cancer cohorts were estrogen, progesterone, and Her2/neu receptor status negative as determined by the pathology report. Histological grade was not available for this study. The subjects were matched for age and race and were nontobacco users.

The participating subjects were given an explanation about their participation rights and signed an IRB consent form. The saliva specimens and related patient data are nonlinked and bar coded in order to protect patient confidentiality. This study was performed under the UTHSC IRB approved protocol number HSC-DB-05-0394. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UTHSC IRB and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983.

2.2. Saliva Collection and Sample Preparation

Stimulated whole salivary gland secretion is based on the reflex response occurring during the mastication of a bolus of food. Usually, a standardized bolus (1 gram) of paraffin or a gum base (generously provided by the Wrigley Co., Peoria, IL) is given to the subject to chew at a regular rate. The individual, upon sufficient accumulation of saliva in the oral cavity, expectorates periodically into a preweighed disposable plastic cup. This procedure is continued for a period of five minutes. The volume and flow rate is then recorded along with a brief description of the specimen's physical appearance [23]. The cup with the saliva specimen is reweighed and the flow rate determined gravimetrically. The authors recommend this salivary collection method with the following modifications for consistent protein analyses [24]. A protease inhibitor from Sigma Co (St. Louis, MI, USA) is added along with enough orthovanadate from a 100 mM stock solution to bring its concentration to 1 mM. The treated samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at top speed in a table top centrifuge. The supernatant was divided into 1 mL aliquots and frozen at −80°C.

2.3. LC-MS/MS Mass Spectroscopy with Isotopic Labeling

Recent advances in mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography, analytical software, and bioinformatics have enabled the researchers to analyze complex peptide mixtures with the ability to detect proteins differing in abundance by over 8 orders of magnitude [25]. One current method is isotopic labeling coupled with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (IL-LC-MS/MS) to characterize the salivary proteome [26]. The main approach for discovery is a mass spectroscopy-based method that uses isotope coding of complex protein mixtures such as tissue extracts, blood, urine, or saliva to identify differentially expressed proteins [27]. The approach readily identifies changes in the level of expression, thus permitting the analysis of putative regulatory pathways providing information regarding the pathological disturbances in addition to potential biomarkers of disease. The analysis was performed on a tandem QqTOF QStar XL mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with an LC Packings (Sunny vale, CA, USA) HPLC for capillary chromatography. The HPLC is coupled to the mass spectrometer by a nanospray ESI head (Protana, Odense, Denmark) for maximal sensitivity [16]. The advantage of tandem mass spectrometry combined with LC is enhanced sensitivity and the peptide separations afforded by chromatography. Thus even in complex protein mixtures MS/MS data can be used to sequence and identify peptides by sequence analysis with a high degree of confidence [21, 25, 26, 28].

Isotopic labeling of protein mixtures has proven to be a useful technique for the analysis of relative expression levels of proteins in complex protein mixtures such as plasma, saliva urine, or cell extracts. There are numerous methods that are based on isotopically labeled protein modifying reagents to label or tag proteins to determine relative or absolute concentrations in complex mixtures. The higher resolution offered by the tandem Qq-TOF mass spectrometer is ideally suited to isotopically labeled applications [21, 26, 29, 30].

Applied Biosystems recently introduced iTRAQ reagents [26, 29, 30], which are amino reactive compounds that are used to label peptides in a total protein digest of a fluid such as saliva. The real advantage is that the tag remains intact through TOF-MS analysis; however, it is revealed during collision-induced dissociation by MSMS analysis. Thus in the MSMS spectrum for each peptide there is a fingerprint indicating the amount of that peptide from each of the different protein pools. Since virtually all of the peptides in a mixture are labeled by the reaction, numerous proteins in complex mixtures are identified and can be compared for their relative concentrations in each mixture. Thus even in complex mixtures there is a high degree of confidence in the identification.

2.4. Salivary Protein Analyses with iTRAQ

Briefly, the saliva samples were thawed and immediately centrifuged to remove insoluble materials. The supernatant was assayed for protein using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA, USA) and an aliquot containing 100 μg of each specimen was precipitated with 6 volumes of −20°C acetone. The precipitate was resuspended and treated according to the manufacturers instructions. Protein digestion and reaction with iTRAQ labels was carried out as previously described and according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Briefly, the acetone precipitable protein was centrifuged in a table—top centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes. The acetone supernatant was removed and the pellet resuspended in 20 uL dissolution buffer. The soluble fraction was denatured and disulfides reduced by incubation in the presence of 0.1% SDS and 5 mM TCEP (tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine)) at 60°C for one hour. Cysteine residues were blocked by incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes with MMTS (methyl methane-thiosulfonate). Trypsin was added to the mixture to a protein : trypsin ratio of 10 : 1. The mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C. The protein digests were labeled by mixing with the appropriate iTRAQ reagent and incubating at room temperature for one hour. On completion of the labeling reaction, the four separate iTRAQ reaction mixtures were combined. Since there are a number of components that can interfere with the LCMSMS analysis, the labeled peptides are partially purified by a combination of strong cation exchange followed by reverse phase chromatography on preparative columns. The combined peptide mixture is diluted 10-fold with loading buffer (10 mM KH2PO4 in 25% acetonitrile at pH 3.0) and applied by syringe to an ICAT Cartridge-Cation Exchange column (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) column that has been equilibrated with the same buffer. The column is washed with 1 mL loading buffer to remove contaminants. To improve the resolution of peptides during LCMSMS analysis, the peptide mixture is partially purified by elution from the cation exchange column in 3 fractions. Stepwise elution from the column is achieved with sequential 0.5 mL aliquots of 10 mM KH2PO4 at pH 3.0 in 25% acetonitrile containing 116 mM, 233 mM, and 350 mM KCl, respectively. The fractions are evaporated by Speed Vac to about 30% of their volume to remove the acetonitrile and then slowly applied to an Opti-Lynx Trap C18 100 uL reverse phase column (Alltech, Deerfield, IL) with a syringe. The column was washed with 1 mL of 2% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid and eluted in one fraction with 0.3 mL of 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. The fractions were dried by lyophilization and resuspended in 10 uL 0.1% formic acid in 20% acetonitrile. Each of the three fractions was analyzed by reverse phase LCMSMS.

2.5. Reverse Phase LCMSMS

The desalted and concentrated peptide mixtures were quantified and identified by nano-LCMS/MS on an API QSTAR XL mass spectrometer (ABS Sciex Instruments) operating in positive ion mode. The chromatographic system consists of an UltiMate nano-HPLC and FAMOS autosampler (Dionex LC Packings). Peptides were loaded on a 75 cm x 10 cm, 3 mm fused silica C18 capillary column, followed by mobile phase elution: buffer (A) 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile/98% Milli-Q water and buffer (B): 0.1% formic acid in 98% acetonitrile/2% Milli-Q water. The peptides were eluted from 2% buffer B to 30% buffer B over 180 minutes at a flow rate 220 nL/min. The LC eluent was directed to a NanoES source for ESI/MS/MS analysis. Using information-dependent acquisition, peptides were selected for collision induced dissociation (CID) by alternating between an MS (1 second) survey scan and MS/MS (3 seconds) scans. The mass spectrometer automatically chooses the top two ions for fragmentation with a 60-second dynamic exclusion time. The IDA collision energy parameters were optimized based upon the charge state and mass value of the precursor ions. In each saliva sample set there are three separate LCMSMS analyses.

2.6. Bioinformatics

The accumulated MSMS spectra are analyzed by ProQuant and ProGroup software packages (Applied Biosystems) using the SwissProt database for protein identification. The ProQuant analysis was carried out with a 75% confidence cutoff with a mass deviation of 0.15 Da for the precursor and 0.1 Da for the fragment ions. The ProGroup reports were generated with a 95% confidence level for protein identification. Protein Pilot software package was used to assess the data produced from the mass spectrometry analyses. The Venn diagrams were constructed using the NIH software program (http://ncrr.pnl.gov). Graphic comparisons with log conversions and error bars for protein expression were produced using the ProQuant software. Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS statistical software.

3. Results

Tables 1–5 summarize the results of the mass spectrometry analysis of the pooled salivary specimens and illustrate protein comparisons between Stage IIa versus healthy and Stage IIb versus healthy. The results identified and compared approximately 174 differentially expressed proteins in the saliva specimens. Of the 174 proteins, 158 (91%) were significant at an alpha level of P < .05 with a 95% confidence level. The mean percent peptide coverage for the complete panel proteins was 63.5% (±19.6) with a range of 35% to 96.5% coverage. The median value was 67.7% coverage.

Table 1.

| Summary of protein expression profiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Up Regulated | Down Regulated | Total Markers |

| Stage IIa versus | 34 | 41 | 75 |

| healthy | |||

| Stage IIb versus | 38 | 45 | 83 |

| healthy | |||

| Totals | 72 | 86 | 158 |

|

| |||

| Stage IIa compared to stage IIb | |||

|

| |||

| Common proteins | 24 | 31 | 55 |

| Differing proteins | 24 | 24 | 48 |

| Totals | 48 | 55 | 83 |

Table 5.

Downregulated salivary proteins for stage IIb (n = 45).

| Accession | Gene ID | Protein Name | Ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P31947 | 1433S | 14-3-3 protein sigma (Stratifin) (Epithelial cell marker protein 1) | 0.5486 | .0000 |

| P63104 | 1433Z | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta (Protein kinase C inhibitor protein 1) | 0.5718 | .0378 |

| P04075 | ALDOA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A (Lung cancer antigen NY-LU-1) | 0.7080 | .0001 |

| P19961 | AMYC | Alpha-amylase 2B precursor | 0.6840 | .0020 |

| P04745 | AMYS | Salivary alpha-amylase precursor | 0.9302 | .0042 |

| P04083 | ANXA1 | Annexin A1 (p35) | 0.8105 | .0080 |

| P23280 | CAH6 | Carbonic anhydrase 6 precursor | 0.4900 | .0000 |

| P10909 | CLUS | Clusterin precursor (Complement-associated protein SP-40,40) | 0.7704 | .0252 |

| P04080 | CYTB | Cystatin-B (Stefin-B) (Liver thiol proteinase inhibitor) | 0.8705 | .0007 |

| P01034 | CYTC | Cystatin-C precursor (Cystatin-3) | 0.5621 | .0000 |

| P28325 | CYTD | Cystatin-D precursor (Cystatin-5) | 0.4856 | .0000 |

| P01037 | CYTN | Cystatin-SN precursor (Cystatin-1) | 0.2323 | .0000 |

| P01036 | CYTS | Cystatin-S precursor (Cystatin-4) | 0.2437 | .0000 |

| P09228 | CYTT | Cystatin-SA precursor (Cystatin-S5) | 0.3033 | .0000 |

| Q02487 | DSC2 | Desmocollin-2 precursor (Desmosomal glycoprotein II and III) | 0.7029 | .0063 |

| P06744 | G6PI | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (SA-36)—(Human) | 0.5118 | .0013 |

| P09211 | GSTP1 | Glutathione S-transferase P | 0.7563 | .0001 |

| Q8IUE6 | H2A2B | Histone H2A type 2-B | 0.5699 | .0058 |

| Q99880 | H2B1L | Histone H2B type 1-L (H2B.c) | 0.6841 | .0373 |

| P62805 | H4 | Histone H4 | 0.3745 | .0000 |

| P15515 | HIS1 | Histatin-1 precursor (Histidine-rich protein 1) | 0.2237 | .0032 |

| P30740 | ILEU | Leukocyte elastase inhibitor (Serpin B1) | 0.9203 | .0418 |

| P13646 | K1C13 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 13 (Cytokeratin-13) | 0.4247 | .0000 |

| P08779 | K1C16 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 16 (Cytokeratin-16) | 0.4900 | .0000 |

| P02538 | K2C6A | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A (Cytokeratin-6A) | 0.6744 | .0019 |

| P61626 | LYSC | Lysozyme C precursor | 0.6646 | .0000 |

| P01871 | MUC | Ig mu chain C region | 0.7992 | .0000 |

| Q9HC84 | MUC5B | Mucin-5B precursor (Mucin-5 subtype B, tracheobronchial) | 0.9357 | .0260 |

| P80303 | NUCB2 | Nucleobindin-2 precursor (Gastric cancer antigen Zg4) | 0.4934 | .0000 |

| P07237 | PDIA1 | Protein disulfide-isomerase precursor (p55) | 0.8132 | .0205 |

| P22079 | PERL | Lactoperoxidase precursor | 0.6879 | .0000 |

| P05164 | PERM | Myeloperoxidase precursor | 0.7856 | .0049 |

| P12273 | PIP | Prolactin-inducible protein precursor (gp17) | 0.4659 | .0000 |

| P62937 | PPIA | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | 0.8031 | .0091 |

| P23284 | PPIB | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B precursor | 0.7089 | .0006 |

| P02812 | PRB2 | Basic salivary proline-rich protein 2 (Salivary proline-rich protein) | 0.4204 | .0000 |

| Q06830 | PRDX1 | Peroxiredoxin-1 | 0.6877 | .0006 |

| P02810 | PRPC | Salivary acidic proline-rich phosphoprotein 1/2 precursor (PRP-1/PRP-2) | 0.6861 | .0000 |

| P05109 | S10A8 | Protein S100-A8 (S100 calcium-binding protein A8) (Calgranulin-A) | 0.8042 | .0000 |

| Q96DR5 | SPLC2 | Lung and nasal epith. carcinoma-assoc. protein 2 precursor | 0.2322 | .0000 |

| P10599 | THIO | Thioredoxin (Trx) (ATL-derived factor) | 0.8003 | .0003 |

| P06753 | TPM3 | Tropomyosin alpha-3 chain (Tropomyosin-3) | 0.8990 | .0215 |

| P02788 | TRFL | Lactotransferrin precursor | 0.7072 | .0000 |

| P08670 | VIME | Vimentin | 0.7717 | .0277 |

| P25311 | ZA2G | Zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein precursor (Zn-alpha-2-glycoprotein) | 0.8543 | .0000 |

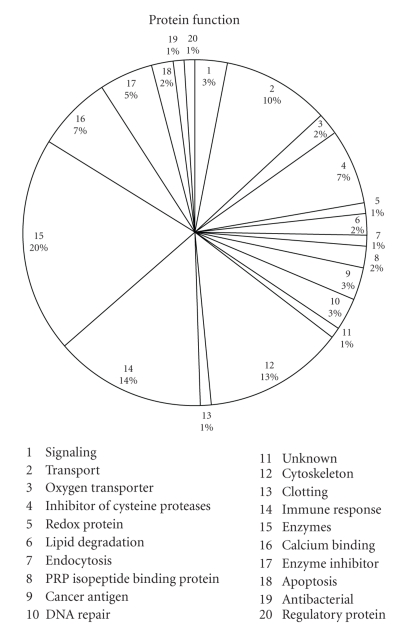

The pie chart in Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of proteins according to protein function. There were 55 proteins that were common to both cancer stages in comparison to each other while there were 20 proteins unique to Stage IIa and 28 proteins that were unique to Stage IIb (Table 1).

Figure 1.

It represents protein function.

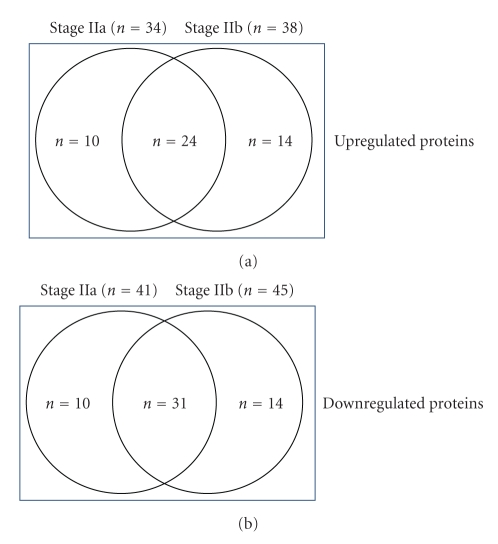

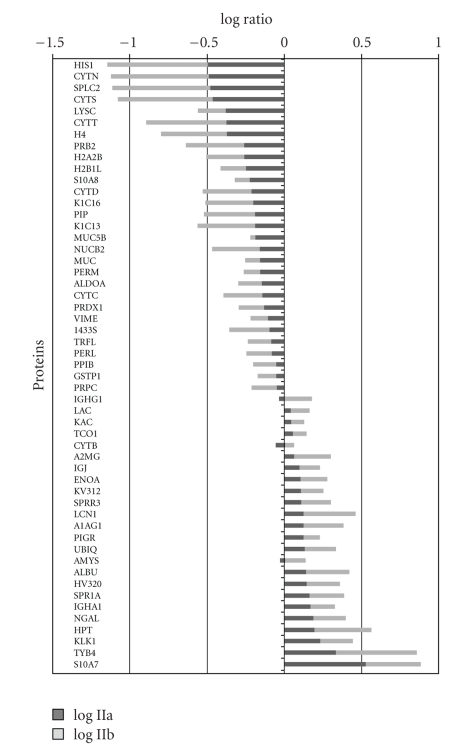

Figure 2 represents a Venn diagram of the overlapping proteins between the three groups of women. Figure 3 illustrates the comparison of the log ratio of the relative intensity (cancer/control) of the proteins which were common to both Stage IIa and Stage IIb while Figure 4 shows the proteins that were different between the two groups. It is worth noting that in Figure 3 the stage IIb protein ratios (; ±0.471) are greater than the stage IIa ratios (; ±0.469) for the same proteins. Consequently, a paired t-test was performed comparing the two groups of values. The difference in the mean values between the two groups is greater than would be expected by chance; there is a statistically significant difference (t = −2.882; P < .008).

Figure 2.

It represents a Venn diagram of the overlapping proteins within stage IIa and stage IIb.

Figure 3.

Differential expressions of salivary proteins common to both stage IIa and stage IIb.

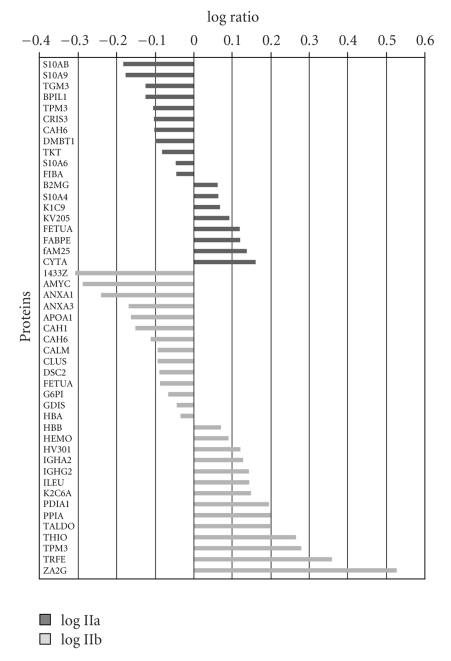

Figure 4.

Differential expressions of salivary proteins that were not common to both stage IIa and stage IIb.

Tables 2 and 3 represent the up- (n = 34) and down- (n = 41) regulated proteins for the pooled saliva sample composed of individuals diagnosed with a Stage IIa IDC. The fold-increase of protein and P-values are also presented. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, 40 of the 75 proteins (53%) were significant at the P < .001 to P < .0001 levels.

Table 2.

Upregulated salivary proteins for stage IIa (n = 34).

| Accession | Gene ID | Name | Ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P02763 | A1AG1 | Alpha-1 acid glycoprotein 1 precursor (AGP 1) | 1.3229 | .0127 |

| P01023 | A2MG | Alpha-2 macroglobulin precursor | 1.1446 | .0324 |

| P07108 | ACBP | AcylCoA binding protein | 1.2264 | .0254 |

| P02768 | ALBU | Serum albumin precursor | 1.3677 | .0000 |

| P04745 | AMYS | Salivary alpha amylase precursor | 1.3564 | .0000 |

| P61769 | B2MG | Beta-2 microglobulin precursor | 1.1463 | .0465 |

| P04040 | CATA | Catalase | 1.0918 | .0183 |

| P01024 | CO3 | Complement C3 precursor | 1.1698 | .0194 |

| P01040 | CYTA | CystatinA (StefinA) (CystatinAS) | 1.4403 | .0005 |

| P04080 | CYTB | CystatinB (StefinB) | 1.1440 | .0108 |

| P06733 | ENOA | Alphaenolase | 1.2626 | .0000 |

| Q01469 | FABPE | Fatty acidbinding protein, epidermal (EFABP) | 1.3126 | .0022 |

| Q5VTM1 | fAM25 | Protein FAM25 | 1.3647 | .0165 |

| P02765 | FETUA | Alpha-2HS glycoprotein precursor | 1.3101 | .0129 |

| P00738 | HPT | Haptoglobin precursor | 1.5562 | .0000 |

| P01781 | HV320 | Ig heavy chain VIII region GAL | 1.3879 | .0336 |

| P01876 | IGHA1 | Ig alpha1 chain C region | 1.4641 | .0000 |

| P01591 | IGJ | Immunoglobulin J chain | 1.2429 | .0002 |

| P35527 | K1C9 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | 1.1629 | .0279 |

| P01834 | KAC | Ig kappa chain C region | 1.0953 | .0016 |

| P06870 | KLK1 | Kallikrein1 precursor | 1.6991 | .0000 |

| P06309 | KV205 | Ig kappa chain VII region GM607 precursor | 1.2300 | .0131 |

| P18135 | KV312 | Ig kappa chain VIII region HAH precursor | 1.2637 | .0077 |

| P01842 | LAC | Ig lambda chain C regions | 1.0933 | .0004 |

| P31025 | LCN1 | Lipocalin1 precursor | 1.3213 | .0000 |

| P80188 | NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin precursor (Oncogene 24p3) | 1.5325 | .0000 |

| P01833 | PIGR | Hepatocellular carcinomaassociated protein TB6 | 1.3233 | .0000 |

| P26447 | S10A4 | Protein S100A4 (S100 calciumbinding protein A4) | 1.1539 | .0027 |

| P31151 | S10A7 | Protein S100A7 (Psoriasin) | 3.3466 | .0000 |

| P35321 | SPR1A | Cornifin-A (19 kDa pancornulin) | 1.4452 | .0093 |

| Q9UBC9 | SPRR3 | Cornifin beta (22 kDa pancornulin) | 1.2787 | .0000 |

| P20061 | TCO1 | Transcobalamin1 precursor | 1.1222 | .0383 |

| P62328 | TYB4 | Thymosin beta 4 | 2.1483 | .0007 |

| P62988 | UBIQ | Ubiquitin | 1.3427 | .0424 |

Table 3.

Downregulated salivary proteins for stage IIa (n = 41).

| Accession | Gene ID | Name | Ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P31947 | 1433S | 14-3-3 protein sigma (Epithelial cell marker protein 1) | 0.7921 | .0043 |

| P04075 | ALDOA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 0.7036 | .0000 |

| Q8N4F0 | BPIL1 | Lung and nasal epith, carcinoma-assoc. protein 2 | 0.7465 | .0002 |

| P23280 | CAH6 | Carbonic anhydrase 6 precursoranhydrase | 0.7871 | .0000 |

| P54108 | CRIS3 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 precursor (CRISP-3) | 0.7846 | .0003 |

| P01034 | CYTC | Cystatin-C precursor (Cystatin-3) | 0.7108 | .0000 |

| P28325 | CYTD | Cystatin-D precursor (Cystatin-5) | 0.6047 | .0000 |

| P01037 | CYTN | Cystatin-SN precursor | 0.3200 | .0000 |

| P01036 | CYTS | Cystatin-S precursor (Cystatin-4) | 0.3385 | .0000 |

| P09228 | CYTT | Cystatin-SA precursor (Cystatin-S5) | 0.4153 | .0000 |

| Q9UGM3 | DMBT1 | Deleted in malignant brain tumors 1 protein precursor (Glycoprotein 340) | 0.7910 | .0050 |

| P02671 | FIBA | Fibrinogen alpha chain precursor [Contains: Fibrinopeptide A] | 0.8964 | .0104 |

| P09211 | GSTP1 | Glutathione S-transferase P | 0.8782 | .0261 |

| Q8IUE6 | H2A2B | Histone H2A | 0.5435 | .0211 |

| Q99880 | H2B1L | Histone H2B type 1-L | 0.5576 | .0008 |

| P62805 | H4 | Histone H4 | 0.4195 | .0000 |

| P15515 | HIS1 | Histatin-1 precursor | 0.3152 | .0340 |

| P01857 | IGHG1 | Ig gamma-1 chain C region | 0.9173 | .0306 |

| P13646 | K1C13 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 13 (Cytokeratin-13) | 0.6395 | .0011 |

| P08779 | K1C16 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 16 (Cytokeratin-16) | 0.6220 | .0001 |

| P61626 | LYSC | Lysozyme C precursor | 0.4121 | .0000 |

| P01871 | MUC | Ig mu chain C region | 0.6877 | .0000 |

| Q9HC84 | MUC5B | Mucin-5B precursor | 0.6404 | .0000 |

| P80303 | NUCB2 | Nucleobindin-2 precursor (Gastric cancer antigen Zg4) | 0.6836 | .0000 |

| P22079 | PERL | Lactoperoxidase precursor | 0.8196 | .0000 |

| P05164 | PERM | Myeloperoxidase precursor | 0.6894 | .0000 |

| P12273 | PIP | Prolactin-inducible protein precursor | 0.6382 | .0000 |

| P23284 | PPIB | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B precursor | 0.8769 | .0326 |

| P02812 | PRB2 | Basic salivary proline-rich protein 2 | 0.5422 | .0000 |

| Q06830 | PRDX1 | Peroxiredoxin-1 | 0.7296 | .0020 |

| P02810 | PRPC | Salivary acidic proline-rich phosphoprotein 1/2 precursor | 0.8848 | .0000 |

| P06703 | S10A6 | Protein S100-A6 (Growth factor-inducible protein 2A9) | 0.8926 | .0051 |

| P05109 | S10A8 | Protein S100-A8 (S100 calcium-binding protein A8) | 0.5888 | .0000 |

| P06702 | S10A9 | Protein S100-A9 (S100 calcium-binding protein A9) | 0.6622 | .0000 |

| P31949 | S10AB | Protein S100-A11 (S100 calcium-binding protein A11) | 0.6526 | .0017 |

| Q96DR5 | SPLC2 | Lung and nasal epith. carcinoma-assoc. protein 2 precursor | 0.3270 | .0000 |

| Q08188 | TGM3 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase E precursor | 0.7454 | .0168 |

| P29401 | TKT | Transketolase | 0.8236 | .0351 |

| P06753 | TPM3 | Tropomyosin alpha-3 chain | 0.7809 | .0016 |

| P02788 | TRFL | Lactotransferrin precursor | 0.8118 | .0000 |

| P08670 | VIME | Vimentin | 0.7728 | .0190 |

Tables 4 and 5 are a list of the up- (n = 38) and down- (n = 45) regulated proteins observed in the Stage IIb cancer as compared to healthy controls. Of these 83 differentially expressed proteins, 54 (65%) were significant at the P < .001 to P < .0001 levels. There were 6 proteins that exhibited a 2.0 or greater fold increase in protein level in the Stage IIb cancer cohort as compared to the control subjects.

Table 4.

Upregulated salivary proteins for stage IIb (n = 38).

| Accession | Gene ID | Name | Ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P02763 | A1AG1 | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 precursor (AGP 1) | 1.8128 | .0003 |

| P01023 | A2MG | Alpha-2-macroglobulin precursor (Alpha-2-M) | 1.7279 | .0000 |

| P02768 | ALBU | Serum albumin precursor | 1.9149 | .0000 |

| P12429 | ANXA3 | Annexin A3 (Annexin III) | 1.3144 | .0058 |

| P02647 | APOA1 | Apolipoprotein A-I precursor (Apo-AI) | 1.2233 | .0012 |

| P00915 | CAH1 | Carbonic anhydrase 1 | 3.3424 | .0356 |

| P62158 | CALM | Calmodulin (CaM) | 1.5783 | .0391 |

| P04040 | CATA | Catalase | 1.4806 | .0007 |

| P01024 | CO3 | Complement C3 precursor | 1.3391 | .0000 |

| P06733 | ENOA | Alpha-enolase | 1.4856 | .0000 |

| P02765 | FETUA | Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein precursor (Fetuin-A) | 1.4004 | .0007 |

| P52566 | GDIS | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 (Rho GDI 2) | 1.3866 | .0046 |

| P69905 | HBA | Hemoglobin subunit alpha (Hemoglobin alpha chain) | 1.8916 | .0000 |

| P68871 | HBB | Hemoglobin subunit beta (Hemoglobin beta chain) | 1.8326 | .0000 |

| P02790 | HEMO | Hemopexin precursor (Beta-1B-glycoprotein) | 2.2691 | .0001 |

| P00738 | HPT | Haptoglobin precursor | 2.3331 | .0000 |

| P01762 | HV301 | Ig heavy chain V-III region TRO | 1.3350 | .0262 |

| P01781 | HV320 | Ig heavy chain V-III region GAL | 1.6357 | .0259 |

| P01876 | IGHA1 | Ig alpha-1 chain C region | 1.4384 | .0000 |

| P01877 | IGHA2 | Ig alpha-2 chain C region | 1.1678 | .0288 |

| P01857 | IGHG1 | Ig gamma-1 chain C region | 1.4955 | .0000 |

| P01859 | IGHG2 | Ig gamma-2 chain C region | 1.5578 | .0000 |

| P01591 | IGJ | Immunoglobulin J chain | 1.3564 | .0000 |

| P01834 | KAC | Ig kappa chain C region | 1.2156 | .0000 |

| P06870 | KLK1 | Kallikrein-1 precursor | 1.6222 | .0000 |

| P18135 | KV312 | Ig kappa chain V-III region HAH precursor | 1.4020 | .0009 |

| P01842 | LAC | Ig lambda chain C regions | 1.3162 | .0000 |

| P31025 | LCN1 | Lipocalin-1 precursor | 2.1725 | .0000 |

| P80188 | NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase-assoc. lipocalin precursor (Oncogene 24p3) | 1.6181 | .0000 |

| P01833 | PIGR | Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated protein TB6 | 1.2753 | .0000 |

| P31151 | S10A7 | Protein S100-A7 (S100 calcium-binding protein A7) | 2.2683 | .0000 |

| P35321 | SPR1A | Cornifin-A(SPR-IA) | 1.6742 | .0084 |

| Q9UBC9 | SPRR3 | Cornifin beta (22 kDa pancornulin) | 1.5506 | .0000 |

| P37837 | TALDO | Transaldolase | 1.3811 | .0053 |

| P20061 | TCO1 | Transcobalamin-1 precursor (Transcobalamin I) | 1.2262 | .0001 |

| P02787 | TRFE | Serotransferrin precursor (Transferrin) | 1.5744 | .0000 |

| P62328 | TYB4 | Thymosin beta-4 (T beta 4) | 3.3412 | .0003 |

| P62988 | UBIQ | Ubiquitin | 1.5925 | .0055 |

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first attempt to determine salivary protein profile alterations related to lymphovascular invasion. As a consequence we have only a few references by which to compare our data.

The proteins listed in Tables 2–4 are common to saliva and are listed in references concerning salivary proteomics of whole saliva and those constituents contributed by individual gland secretions [21, 31–34]. Likewise, many of the proteins are common to those identified in proteomic studies of cancer cell lines and serum or plasma from individuals diagnosed with IDC [21, 27, 35–39]. Additionally, there is a proteomic study by Pei et al. [40] that compared proteomic tissue protein profiles from paired normal tissue to malignant tissues with and without lymphovascular invasion [40]. Their results yielded 25 differentially expressed proteins among node positive and node negative, adenocarcinoma, colorectal cancer patients. From the list of 25 proteins that were differentially expressed when compared to a normal control by Pei et al., we matched 8 (32%) of them. These proteins were Apo-A1 protein, vimentin, cytokeratin-8, glutathione s-transferase, keratin 1, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, alpha enolase, and transferring precursor [40]. Pei also reports Annexin II and IV while we found members Annexin I and III of the same family of proteins. Pei et al. identified four proteins which were differentially expressed. These were heat shock protein 27 (HSP-27), glutathione S-transferase (GST), Annexin II, and liver-fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP). The authors of this manuscript found 48 differentially expressed proteins (Figure 4) which included GST and a family member of the fatty acid binding proteins, epidermal-fatty acid binding protein.

A second by Li et al. [41] used metastatic (lymph nodes) breast cancer cell lines that they developed in order to produce protein profile comparisons [41]. Comparative proteomic analysis using 2-DE and LC-IT-MS revealed that 102 protein gel spots were altered more than three-fold between the variant and its parental counterpart. Using SEQUEST with uninterpreted tandem mass raw data, they found eleven differentially expressed protein spots that were identified with high confidence. The proteins were identified as Cathepsin D precursor, peroxiredoxin 6 (PDX6), heat shock protein 27 (HSP27), HSP60, tropomyosin 1 (sent in the highly metastatic variant, whereas alpha B-crystalline (CRAB) was only detected in its parTPM1), TPM2, TPM3, TPM4, 14-3-3 protein epsilon, and tumor protein D54. The proteins were preental counterpart [41]. As shown in Tables 2–5, we identified a number of the same proteins. For example, the 14-3-3, tropomyosin and the peroxiredoxin family of proteins were found to be altered in the saliva of our late stage cancer profiles as well. Of particular interest is the fact that these proteins were not altered in the profiles of early stage cancer, that is, Stage 0 and Stage I performed by the authors of this manuscript [21, 42].

5. Conclusions

The authors have examined the salivary proteome that is altered in the presence of carcinoma of the breast with and without lymph node metastasis. We do not want to over emphasize the findings at this point, but we are encouraged to find that these protein profiles are found to be altered in the supernants from cancer tissues which provide additional support to our findings.

The authors urge the exploration of saliva proteomics for in vivo systems modeling of carcinoma of tissues of ectodermal origin. Saliva can also be described as a media which provides “real-time” results [43]. The fluid is continually produced and excreted in an open-ended circuit, unlike blood which exists in a “closed-loop.” Blood, a circulating media, may contain proteins that are a day, a week, or a month old as well as proteins which have passed numerous times through many organ systems or have been excreted [43]. Saliva, with its continuous flow, is not subject to the aforementioned effects. Consequently, saliva and nipple aspirates may be a more useful than blood as the protein profiles of these fluids easier to assay than blood and are both altered in the presence of malignant diseases [16, 43].

Further study is required to determine their diagnostic utility. The authors plan to validate the protein biomarkers by western blot using commercially available antibodies. ELISA will also be used to assay a larger sample size and determine the sensitivity and specificity of the biomarkers. It is the hope of the investigators that this preliminary research will establish the foundation for a “point-of-care” test for clinical decision making in the treatment of carcinoma of the breast.

6. Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by a Grant from the Gillson-Longenbaugh Foundation.

References

- 1.Silverstein MJ, Skinner KA, Lomis TJ. Predicting axillary nodal positivity in 2282 patients with breast carcinoma. World Journal of Surgery. 2001;25(6):767–772. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivotto IA, Jackson JSH, Mates D, et al. Prediction of axillary lymph node involvement of women with invasive breast carcinoma: a multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1998;83(5):948–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gann PH, Colilla SA, Gapstur SM, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Factors associated with axillary lymph node metastasis from breast carcinoma. Descriptive and predictive analyses. Cancer. 1999;86(8):1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1511::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliano AE, Barth AM, Spivack B, Beitsch PD, Evans SW. Incidence and predictors of axillary metastasis in T1 carcinoma of the breast. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1996;183(3):185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher B, Bauer M, Wickerham DL, et al. Relation of number of positive axillary nodes to the prognosis of patients with primary breast cancer. An NSABP update. Cancer. 1983;52(9):1551–1557. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831101)52:9<1551::aid-cncr2820520902>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989;63(1):181–187. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<181::aid-cncr2820630129>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher ER, Anderson S, Tan-Chiu E, Fisher B, Eaton L, Wolmark N. Fifteen-year prognostic discriminants for invasive breast carcinoma: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol-06. Cancer. 2001;91(8):1679–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilke LG, McCall LM, Posther KE, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node biopsy: results from a prospective international cooperative group trial. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2006;13(4):491–500. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuliano AE, Jones RC, Brennan M, Statman R. Sentinel lymphadenectomy in breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(6):2345–2350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa T, Huang SK, Martinez SR, et al. Proteomic profiling of primary breast cancer predicts axillary lymph node metastasis. Cancer Research. 2006;66(24):11825–11830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wick MR, Ockner DM, Mills SE, Ritter JH, Swanson PE. Homologous carcinomas of the breasts, skin, and salivary glands: a histologic and immunohistochemical comparison of ductal mammary carcinoma, ductal sweat gland carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1998;109(1):75–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimura T, Sumida T, Liu S, et al. Growth inhibition of human salivary gland tumor cells by introduction of progesterone (Pg) receptor and Pg treatment. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2007;14(4):1107–1116. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapadia SB, Barnes L. Expression of androgen receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and CD44 in salivary duct carcinoma. Modern Pathology. 1998;11(11):1033–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh F, Umemura S, Osamura RY. Immunohistochemical analysis of GCDFP-15 and GCDFP-24 in mammary and non-mammary tissue. Breast Cancer. 2000;7(1):49–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02967188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurachi H, Okamoto S, Oka T. Evidence for the involvement of the submandibular gland epidermal growth factor in mouse mammary tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(17):5940–5943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuerer HM, Thompson PA, Krishnamurthy S, et al. High and differential expression of HER-2/neu extracellular domain in bilateral ductal fluids from women with unilateral invasive breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(2):601–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streckfus CF, Bigler L, Dellinger T, Dai X, Kingman A, Thigpen JT. The presence of soluble c-erbB-2 in saliva and serum among women with breast carcinoma: a preliminary study. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(6):2363–2370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose DP. Hormones and growth factors in nipple aspirates from normal women and benign breast disease patients. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 1992;16(1):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varnum SM, Covington CC, Woodbury RL, et al. Proteomic characterization of nipple aspirate fluid: identification of potential biomarkers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2003;80(1):87–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1024479106887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawlik TM, Hawke DH, Liu Y, et al. Proteomic analysis of nipple aspirate fluid from women with early-stage breast cancer using isotope-coded affinity tags and tandem mass spectrometry reveals differential expression of vitamin D binding protein. BMC Cancer. 2006;6, article 68 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streckfus CF, Mayorga-Wark O, Arreola D, Edwards C, Bigler L, Dubinsky WP. Breast cancer related proteins are present in saliva and are modulated secondary to ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer Investigation. 2008;26(2):159–167. doi: 10.1080/07357900701783883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6th edition. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2002. Part VII breast; pp. 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birkhed D, Heintze U. Salivary secretion rate, buffer capacity, and pH. In: Tenovuo JO, editor. Human Saliva: Clinical Chemistry and Microbiology, Volume 1. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streckfus CF, Bigler L, Dellinger T, et al. Reliability assessment of soluble c-erbB-2 concentrations in the saliva of healthy women and men. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology & Endodontics. 2001;91(2):174–179. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.111758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilmarth PA, Riviere MA, Rustvold DL, Lauten JD, Madden TE, David LL. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography study of the human whole saliva proteome. Journal of Proteome Research. 2004;3(5):1017–1023. doi: 10.1021/pr049911o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu S, Liu Z, Pan S, et al. Global investigation of p53-induced apoptosis through quantitative proteomic profiling using comparative amino acid-coded tagging. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2004;3(10):998–1008. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400033-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polanski M, Anderson NL. A list of candidate cancer biomarkers for targeted proteomics. Biomarker Insights. 2006;2:1–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shevchenko A, Chernushevich I, Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Mann M. “De novo” sequencing of peptides recovered from in-gel digested proteins by nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Molecular Biotechnology. 2002;20(1):107–118. doi: 10.1385/mb:20:1:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koomen JM, Zhao H, Li D, Abbruzzese J, Baggerly K, Kobayashi R. Diagnostic protein discovery using proteolytic peptide targeting and identification. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2004;18(21):2537–2548. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward LD, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ. Strategies for internal amino acid sequence analysis of proteins separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Journal of Chromatography. 1990;519(1):199–216. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(90)85148-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu S, Xie Y, Ramachandran P, et al. Large-scale identification of proteins in human salivary proteome by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis-mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2005;5(6):1714–1728. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang C-M. Comparative proteomic analysis of human whole saliva. Archives of Oral Biology. 2004;49(12):951–962. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitorino R, Lobo MJC, Ferrer-Correira AJ, et al. Identification of human whole saliva protein components using proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4(4):1109–1115. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghafouri B, Tagesson C, Lindahl M. Mapping of proteins in human saliva using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and peptide mass fingerprinting. Proteomics. 2003;3(6):1003–1015. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minafra IP, Cancemi P, Fontana S, et al. Expanding the protein catalogue in the proteome reference map of human breast cancer cells. Proteomics. 2006;6(8):2609–2625. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wulfkuhle JD, Sgroi DC, Krutzsch H, et al. Proteomics of human breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Research. 2002;62(22):6740–6749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somiari RI, Sullivan A, Russell S, et al. High-throughput proteomic analysis of human infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. Proteomics. 2003;3(10):1863–1873. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudelist G, Singer CF, Pischinger KID, et al. Proteomic analysis in human breast cancer: identification of a characteristic protein expression profile of malignant breast epithelium. Proteomics. 2006;6(6):1989–2002. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chambery A, Farina A, Di Maro A, et al. Proteomic analysis of MCF-7 cell lines expressing the zinc-finger or the proline-rich domain of retinoblastoma-interacting-zinc-finger protein. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5(5):1176–1185. doi: 10.1021/pr0504743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pei H, Zhu H, Zeng S, et al. Proteome analysis and tissue microarray for profiling protein markers associated with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Journal of Proteome Research. 2007;6(7):2495–2501. doi: 10.1021/pr060644r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li D-Q, Wang L, Fei F, et al. Identification of breast cancer metastasis-associated proteins in an isogenic tumor metastasis model using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and liquid chromatography-ion trap-mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2006;6(11):3352–3368. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Streckfus CF, Bigler LR, Dubinsky WP, Bull J. Salivary biomarkers for the detection of cancer. In: Swenson LI, editor. Progress in Tumor Marker Research. New York, NY, USA: Nova Scientific; 2007. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bigler LR, Streckfus CF, Dubinsky WP. Salivary biomarkers for the detection of malignant tumors that are remote from the oral cavity. In: Petricoin EF, editor. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, Proteomics in Laboratory Medicine. Vol. 29. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]