Abstract

Polymicrogyria is a malformation of cortical development characterized by loss of the normal gyral pattern, which is replaced by many small and infolded gyri separated by shallow, partly fused sulci, and loss of middle cortical layers. The pathogenesis is unknown, yet emerging data supports the existence of several loci in the human genome. We report on the clinical and brain imaging features, and results of cytogenetic and molecular genetic studies in 29 patients with polymicrogyria associated with structural chromosome rearrangements. Our data map new polymicrogyria loci in chromosomes 1p36.3, 2p16.1-p23, 4q21.21-q22.1, 6q26-q27, and 21q21.3-q22.1, and possible loci in 1q44 and 18p as well. Most and possibly all of these loci demonstrate incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. We anticipate that these data will serve as the basis for ongoing efforts to identify the causal genes located in these regions.

Keywords: chromosome 1p36, chromosome 1q4, chromosome 2p, chromosome 4q2, chromosome 6q2, chromosome 18p, chromosome 21q2, deletion, duplication, polymicrogyria

INTRODUCTION

Polymicrogyria (PMG), recognized since at least 1899 [Bresler 1899], is characterized by an irregular brain surface, loss of the normal gyral pattern which is replaced by numerous small and infolded gyri separated by shallow sulci that are partly fused in their depths, and reduction of the normal 6-layered to a 4-layered or unlayered cortex [Crome 1952; Ferrer 1984; Leventer 2007; Levine et al., 1974]. PMG most often occurs as an isolated cortical malformation, but may be associated with other brain malformations including agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC), microcephaly (MIC) or megalencephaly, periventricular nodular heterotopia (PNH), hydrocephalus (HYD), cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH) or more diffuse cerebellar hypoplasia (CBLH). It is a relatively common malformation with a rate of at least 0.01 per 1,000 livebirths in a population-based monitoring program (program personnel, Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program, Birth Defects and Genetic Diseases Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, personal communication, 2001). The frequency is probably higher as affected individuals were ascertained only if the diagnosis was recorded in hospital records during the first six years of life, likely underestimating the true incidence.

Several subtypes of PMG have been recognized based on differences in topography, such as diffuse or generalized, frontal, perisylvian, mesial parieto-occipital, and multilobar forms [Barkovich et al., 1999; Guerrini et al., 2000; Guerrini et al., 1997; Guerrini et al., 1998; Kuzniecky et al., 1993]. We have recognized several other types including posterior PMG [Ferrie et al., 1995], parasagittal PMG, and diffuse (or perisylvian) PMG with abnormal white matter (both as yet unpublished), as well as frontal or posterior predominate PMG with PNH [Wieck et al., 2005]. The perisylvian form accounts for 60–70% of patients, with all other forms being uncommon [Leventer 2007; Leventer et al., 2001]. Several forms of severe congenital microcephaly have PMG including MIC with PMG and PNH [Wieck et al., 2005], with diffuse PMG only, and with asymmetric PMG (see Figures H-L in [Dobyns and Barkovich 1999]). Similarly, several forms of megalencephaly have been associated with PMG including megalencephaly with mega-corpus callosum and PMG [Gohlich-Ratmann et al., 1998], MPPH [Mirzaa et al., 2004], and the CMTC-macrocephaly syndrome [Giuliano et al., 2004; Moore et al., 1997].

Despite numerous descriptions over many years, the pathogenesis of PMG remains poorly understood and likely heterogeneous. Many older reports support extrinsic in utero causes – most supporting a vascular pathogenesis – such as intrauterine cytomegalovirus infection, placental perfusion failure often related to twinning, and maternal exposure to warfarin in the second trimester, and point to a period of risk between 13 and 24 weeks gestation [Barkovich and Lindan 1994; Barth 1992; Barth and van der Harten 1985; Curry et al., 2005; Hayward et al., 1991; Iannetti et al., 1998; Norman 1980].

A genetic basis for some forms of PMG has been proposed based on reports of familial recurrence consistent with autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance [Bartolomei et al., 1999; Borgatti et al., 1999; Caraballo et al., 2000; Ferrie et al., 1995; Guerreiro et al., 2000; Hilburger et al., 1993], and from association with several chromosome abnormalities, such as deletion 22q11.2 or DiGeorge syndrome [Robin et al., 2006]. While PMG has been reported in patients with deletion or duplication of other chromosome regions, documentation has typically been limited.

Here, we describe the clinical and brain imaging features, and results of molecular genetic analysis in a series of 29 patients with PMG associated with various unbalanced chromosome constitutions ascertained from more than 800 patients with PMG in our large Brain Malformation and Deletion 1p36 databases. We have excluded patients with PMG and deletion 22q11.2 as these were reported previously [Robin et al., 2006]. Our data support the existence of 5 novel PMG loci in chromosomes 1p36.3, 2p16.1-p23, 4q21.21-q22.1, 6q26-q27 and 21q2, as well as possible loci in 1q44 and 18p. Other recent papers or abstracts suggest additional loci in 2p15-p16, 11q12-q13 and 13q14.1-q31.2 as well [Dupuy et al., 1999; Kogan et al., 2005].

METHODS

Subjects

We searched our primary brain malformation subject database (W.B.D.) for all patients with PMG including those with known chromosome deletion or duplication, and our deletion 1p36 database (L.G.S.) for patients with PMG. Some were ascertained following our specific requests for referral of patients with chromosome abnormalities, so that ascertainment in both groups of patients was biased. We reviewed clinical summaries, brain imaging studies, and clinical photographs, and requested blood or other samples following Informed Consent with appropriate institutional approval. Clinical data were entered into a spreadsheet, with additional records requested when needed.

All brain imaging studies were reviewed (W.B.D., R.J.L.) looking for characteristic changes of PMG including irregular or pebbled brain surface, abnormal gyral pattern, microgyri within the cortex, and irregular gray-white border. The severity of the cortical malformation was assessed using a grading system we developed for perisylvian PMG, in which the cortical malformation is most severe in the perisylvian region even when it extends to involve other regions of the cortex [Leventer 2007; Leventer et al., 2001]. Grade 1 PMG involves the entire perisylvian region with extension to include one or both poles. Grade 2 involves the entire perisylvian region with extension to other brain regions but not involving either pole. Grade 3 PMG involves the entire perisylvian region without further extension, and grade 4 involves only the posterior perisylvian region. We assessed whether the cortical malformation was more severe on the right versus left side by visual inspection.

Breakpoint mapping

The 29 patients have been ascertained over many years, so that the methods of analysis have changed. Chromosome analysis was done at the referring institution for all patients, and was reported as abnormal in all but one patient, although for a few patients (i.e. the LP87-010 family) this required several attempts. No further studies were done for eight patients. We performed fine mapping of the breakpoints by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in 11 patients. BAC clones from the regions of interest were identified from the Ensembl (www.ensembl.org) and UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) genome databases. FISH was performed using standard methods [Shaffer et al., 1994].

We performed array comparative genome hybridization (aCGH) in ten patients using four platforms. Five patients with deletion 1p36.3 were studied using either an array containing 97 clones covering the most distal 10.5 Mb of 1p36 [Yu et al., 2003], or the SignatureChip® from Signature Genomic Laboratories, LLC (Spokane, WA; http://www.signaturegenomics.com/). The remaining patients were studied using a ~19,000 whole genome BAC microarray available from the Roswell Park Cancer Institute [Cowell 2004; Cowell et al., 2004], the Human Genome CGH Microarray Kit 44B® from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, CA)[Barrett et al., 2004], or the Genome-Wide Human SNP GeneChip® Array 5.0 from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA)[Ogawa et al., 2007]. In all 10 patients, copy number changes were seen in multiple contiguous BACs or clones. To confirm these results, metaphase FISH was performed with probes selected from the deleted or duplicated segments found on the microarrays. Deletion sizes (Table I) were estimated in accordance with the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site (Human March 2006 assembly; hg18).

Table 1.

Cytogenetic abnormalities in 30 patients with PMG

| Subject #a | Karyotype | Critical Regionb | Method | BP1c | BP2c | Size (Mb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR06-214 | 1p#52 | 46,XY,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP11-340B24 | 1pter | 10.9 |

| LP99-072 | 1p#36 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP5-1113E3 | 1pter | 10.4 |

| LP98-109 | 1p#53 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP4-575L21 | 1pter | 10.1 |

| LR04-027 | 1p#92 | 46,XY,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | aCGH/FISH | RP11-807G9 | 1pter | 10.0 |

| LP99-182 | 1p#54 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP5-963K15 | 1pter | 9.0 |

| LR01-161 | 1p#34 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | aCGH/FISH | RP5-892F13 | 1pter | 7.9 |

| LR01-160 | 1p#14 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP3-467L1 | 1pter | 7.7 |

| LR01-382 | 1p#47 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP11-92O17 | 1pter | 7.5 |

| LR06-133 | 1p#59 | 46,XY,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP3-453P22 | 1pter | 7.3 |

| LR01-380 | 1p#66 | 46,XY,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | aCGH/FISH | RP11-312B8 | 1pter | 6.8 |

| LR02-165 | 1p#91 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | aCGH/FISH | RP1-120G22 | 1pter | 6.2 |

| LR01-159 | 1p#05 | 46,XY,der(1)t(1;1)(p36.3;q44) | 1p36.3 | FISH | RP1-58B11 | RP11-656O22 | 5.5, 1.3 |

| LR01-383 | 1p#23 | 46,XX,del(1)(p36.3) | 1p36.3 | aCGH/FISH | RP5-1096P7 | 1pter | 4.8 |

| LP94-079 | 46,XX,der(1)t(1;11)(q44;p15.3) | 1q44 | FISH | RP11-518L10d | 1qter | 4.5 | |

| LR00-173 | 46,XY,dup(2)(p13-p23) | 2p16.1-p23.1 | Cyto | --- | --- | ~50 | |

| LP99-112 | 46,XX,dup(2)(p16.1-p23.1) | 2p16.1-p23.1 | aCGH/FISH | RP11-162J17 | RP11-373L24 | 30.7 | |

| LR04-022a2 | 46,XY,del(4)(q21.21q22.1) | 4q21.21-q22.1 | aCGH/FISH | RP11-90N19 | RP11-49M7 | 9.3 | |

| LR07-256 | 46,XY,del(4)(q21.2q23) | 4q21.21-q22.1 | aCGH/Cyto | chr4:80,044,702 | 100,378,930 | 20 | |

| LP87-010a1 | 46,XY, −6,+der(6),t(6;21)(q25.3;p11) | 6q26-qter | Cyto | --- | 6qter | --- | |

| LP87-010a2 | 46,XX, −6,+der(6),t(6;21)(q25.3;p11) | 6q26-qter | Cyto | --- | 6qter | --- | |

| LP87-010a3 | 46,XY, −6,+der(6),t(6;21)(q25.3;p11) | 6q26-qter | Cyto | --- | 6qter | --- | |

| LP87-010a4 | 46,XY, −6,+der(6),t(6;21)(q25.3;p11) | 6q26-qter | Cyto | --- | 6qter | --- | |

| LR05-261 | 46,XX,del(6)(q25.3) | 6q26-qter | aCGH/FISH | RP1-249F5 | 6qter | 10.4 | |

| LR00-218 | 46,XY,del(6)(q26) | 6q26-qter | aCGH/FISH | RP11-664L13e | 6qter | 9.49 | |

| LP99-104a1 | Pt. 4 | 46,XX,del(6)(q26) | 6q26-qter | FISH | RP11-57O22 | 6qter | 7.35 |

| LP99-104a2 | Pt. 5 | 46,XX,del(6)(q26) | 6q26-qter | FISH | RP11-57O22 | 6qter | 7.35 |

| LP99-062 | 46,XX,del(18)(p11.1) | 18p | Cyto | --- | 18pter | --- | |

| LR00-219 | 45,XY, −21,der(18),t(18;21)(p11.2,q22.1) | 18p, 21q2 | Cyto | ---, 21cen | 18pter, | --- | |

| LR05-078 | 46,XX,del(21)(q21.3-q22.1) | 21q2 | Cyto | --- | 21qter | --- | |

The first column numbers come from our Brain Malformation Database (Dobyns) and second column from our 1p– Database (Shaffer) or their patient number in the previous report.

The critical regions indicate the shortest region of overlap among multiple patients when this could be determined.

BP1 indicates the last non-deleted clone centromeric to the bp, while BP2 indicates the first non-deleted clone telomeric to the bp for interstitial deletions and duplications, or the last non-deleted clone on the other chromosome for translocations.

This clone was split by FISH.

This deletion was visible and assigned a breakpoint in 6q25.3 but non-deleted clone RP11-664L13 is located in 6q26. Seventeen patients have been previously reported including 10 of 13 patients with deletion 1p36 [Heilstedt, 2003 #3084], LP94-079 [Boland, 2007 #3036], the LP87-010 family [Curry, 2000 #327], and LP99-104a1 and a2 [Eash, 2005 #3076].

RESULTS

We found 29 patients with PMG and cytogenetic deletions or duplications at seven different loci (Table I). The deletions or duplications were large enough to be visible with sizes between 4.5 and 10.9 Mb, except for one 20 Mb deletion and one 30.7 Mb duplication. The largest group of patients consists of 13 children with deletion 1p36.3, and includes 13 of 64 patients from our deletion 1p36 database. The remainder consists of eight patients with deletion 6q26-qter, two with duplication 2p16-p23, two with deletion 4q21.21-q22.1, single patients with deletion 1q44, 18p or 21q2, and one with deletion of both 18p and 21q2.

Details regarding the general, developmental and neurologic phenotypes are summarized in Supplementary Tables I and II. As expected, these generally matched published reports with the addition of more details regarding the neurological problems and brain imaging. However, only limited data are available regarding deletion 4q2 or 21q2, or duplication 2p16.1-p23. The brain imaging findings are summarized in Table 2 with representative images shown in Figures 1–4 and Supplementary Figure 1. All but deletion 6q26 are associated with perisylvian PMG, which is by far the most common subtype [Leventer 2007; Leventer et al., 2001].

Table 2.

Polymicrogyria and other brain anomalies

| Subject # | Locus | PMG | HET | LV | Midline | CBL | WM | Prior reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Grade | Sym. | Location | ||||||||

| LR06-214 | 1p#52 | 1p36.3 | PS | R2 | R>L | none | DIL | N | N | --- | [Heilstedt, 2003 #3084] |

| LP99-072 | 1p#36 | 1p36.3 | PS | L4-R1 | R>L | none | R>L | Thin | N | Abn | “ |

| LP98-109 | 1p#53 | 1p36.3 | PS | L2-R1 | R>L | L FH | DIL | Thin | CVH | --- | “ |

| LR04-027 | 1p#92 | 1p36.3 | PS | 4 | SYM | none | N | N | N | --- | |

| LP99-182 | 1p#54 | 1p36.3 | PS | 4 | R>L | none | DIL | Thin, CSP | N | N | [Heilstedt, 2003 #3084] |

| LR01-161 | 1p#34 | 1p36.3 | PS | 2 | SYM | none | DIL | N | N | Abn | “ |

| LR01-160 | 1p#14 | 1p36.3 | PS | 4 | SYM | none | DIL | Thin, CSP | N | Abn | “ |

| LR01-382 | 1p#47 | 1p36.3 | PS | R4 | R>L | none | N | N | N | Abn | “ |

| LR06-133 | 1p#59 | 1p36.3 | PS | 4 | L>R | none | R>L | N | CBLH | Abn | “ |

| LR01-380 | 1p#66 | 1p36.3 | PS | 1 | SYM | none | DIL | N | N | Abn | |

| LR02-165 | 1p#91 | 1p36.3 | PS | R4 | R>L | none | DIL | N | N | N | |

| LR01-159 | 1p#05 | 1p36.3 | PS | L1-R4 | L>R | none | L>R | N, CSP | N | --- | [Heilstedt, 2003 #3084] |

| LR01-383 | 1p#23 | 1p36.3 | PS | 4 | R>L | R FH, L TRI | DIL | ACC | N | Abn | “ |

| LP94-079 | 1q44 | PS | 2 | SYM | --- | N | N | CBLH | [Boland, 2007 #3036] | ||

| LP99-112 | 2p16.1-p23.1 | PS | 1 | SYM | none | N | N | N | |||

| LR00-173 | 2p16.1-p23.1 | PS | 1 | SYM | none | HYD | N | N | |||

| LR04-022a2 | 4q21.21-q22.1 | PS | 1 | SYM | none | HYD | N | MCM | |||

| LR07-256 | 4q21.21-q22.1 | PS | 1 | SYM | None | DIL | N | CVH | |||

| LP87-010a1 | 6q26 | PS-TL | --- | SYM | --- | HYD | N | N | [Curry, 2000 #327] | ||

| LP87-010a2 | 6q26 | PS-TL | 2 | SYM | L>R TRI | DIL | Thin | CVH | “ | ||

| LP87-010a3 | 6q26 | +++ | --- | --- | --- | HYD | Thin, ASP | CBLH | “ | ||

| LP87-010a4 | 6q26 | +++ | --- | SYM | none | HYD | Thin | CBLH | Thin | “ | |

| LR05-261 | 6q26 | PS-TL | --- | SYM | TH | R TH | ACC | CBLH | |||

| LR00-218 | 6q26 | PS-TL | 2 | SYM | none | HYD | Thin | CBLH | |||

| LP99-104a1 | Pt. 4 | 6q26 | PS-TL | na | SYM | TH | DIL | N | N | [Eash, 2005 #2994] | |

| LP99-104a2 | Pt. 5 | 6q26 | PS-TL | na | SYM | TH | HYD | Thin* | N | “ | |

| LP99-062 | 18p | PS | R1 | R>L | none | DIL | N | N | |||

| LR00-219 | 18p, 21q2 | PS | 1 | SYM | none | DIL | Thin | CVH | |||

| LR05-078 | 21q2 | PS | 3 | SYM | none | N | ACC | N | |||

Abbreviations: Abn, abnormal white matter signal; ACC, partial agenesis of the corpus callosum; CBL, cerebellum; CBLH, diffuse cerebellar hypoplasia; CSP, cavum septi pellucidi et vergae; CVH, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia; DIL, dilated; HYD, hydrocephalus; L, left; L>R, left more severe than R; Midline, corpus callosum and septum pellucidum; N, normal; na, not applicable; PS, perisylvian; R, right; R>L, right more severe than left; SYM, symmetric; TH, temporal horns; TL, temporal lobe; TRI, trigone of lateral ventricles; WM, white matter; ---, too few or suboptimal images to determine. See text for explanation of PMG grades.

unclear if primary partial ACC or secondary destruction due to hydrocephalus.

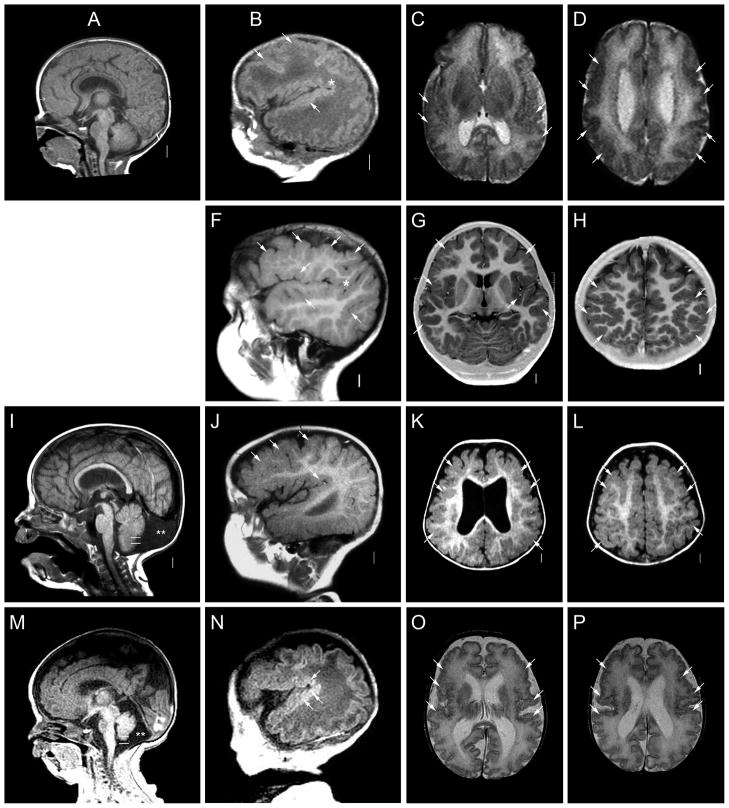

Figure 1.

Brain images from four patients with deletion 1p36 including LP98-109 (A–D), LP99-072 (E–H), LP99-182 (I–L) and LR01-380 (M–P). These images demonstrate extensive areas of polymicrogyria (PMG, white or black arrows in many images) characterized by an irregular gyral pattern with abnormally wide sulci that are often too shallow or deep, as well as variably thick cortex. The PMG appears most severe in the posterior frontal and perisylvian regions and may be asymmetric. Here, the cortical malformation appears symmetric in two patients (C–D, O–P), mildly asymmetric in one (K–L) and strikingly asymmetric in another (G–H). In both asymmetric patients, the PMG is more severe on the right (left side of image as shown). Midline sagittal images show a mildly thin corpus callosum (arrowheads in A, E, I), and parasagittal images demonstrate an extended sylvian fissure (asterisks in B, F, N).

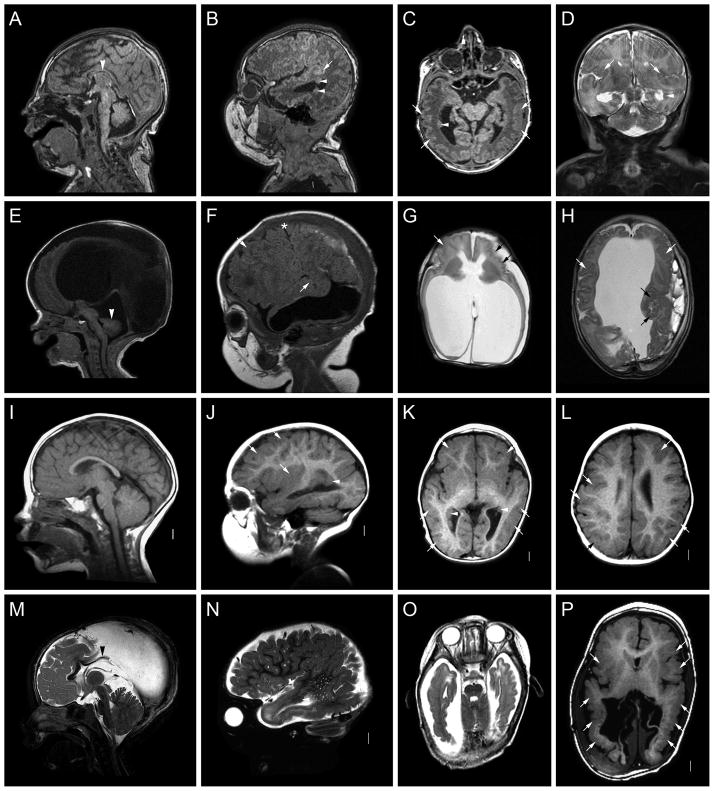

Figure 4.

Brain images from patients with del 18p (A–D, LP99-062), del 18p and 21q2 (E–H, LR00-219), and del 21q2 (I–L, LR05-078). These images show variable areas of PMG (white or black arrows in many images). In the girl with del 18p, the cortical abnormality involves the perisylvian and posterior regions on the right (C, D). In the boy with del 18p plus del 21q2, the PMG involves the entire cortex except for the mesial frontal lobes and appears most severe in the posterior frontal and perisylvian regions (G, H). In the girl with del 21q2, the PMG involves only the perisylvian regions (K, L). Midline sagittal images show dysplastic corpus callosum in one patient consisting of absent rostrum and small genu (arrowhead in I).

Additional Locus Specific Results

Deletion 1p36.3

We found PMG in 13 of 64 patients with brain imaging studies performed from our deletion 1p36 database (L.G.S.) with the smallest deleting the last 4.8 Mb of 1p36 and establishing a critical region between BAC RP5-1096P7 and the telomere (Table I). Because none of our eight subjects with interstitial deletions manifested PMG, and all of the interstitial deletions retained the distal 1 Mb of telomere sequence, we hypothesize that the putative PMG causal gene is localized between 1.0 Mb and 4.8 Mb from the 1p telomere. We identified PMG in 6 of 18 patients with deletions larger than 4.8 Mb, and so estimate the penetrance to be about 33%. Another three patients from our 1p36 database had possible areas of PMG, but the scan resolution was too low for us to be certain. Among the 13 patients with confirmed PMG, the malformation was symmetric in seven and asymmetric in six patients, with five more severe on the right and only one more severe on the left (Table II, Fig 1). The asymmetry is slightly skewed to the right hemisphere but does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.18), primarily due to the small numbers. We found similar asymmetry with the right hemisphere more often and more severely affected among patients with PMG associated with deletion 22q11.2 that did reach statistical significance [Robin et al., 2006]. Most patients with deletion 1p36 had abnormal white matter signal, and a few had other malformations such as PNH, enlarged lateral ventricles or mild CVH, but none had HYD.

Duplication 2p16.1p23

Both of our patients had symmetric perisylvian PMG extending to involve most of the brain, and the boy with the larger deletion also had HYD (Table II, Fig 2). We confirmed the abnormality in LR00-173 by FISH (Supplementary Figure 2), and used aCGH in patient LP99-112 to amend the cytogenetic breakpoints from p13-p15 to p16.1-p23.1, and mapped the putative PMG locus to a large 30 Mb region (Table I).

Figure 2.

Brain images from patients with dup 2p16-p23 (A–D, LP99-112 and E–H, LR00-173), and del 4q21-q22 or q23 (I–L, LR04-022a2 and M–P, LR07-256). These images show extensive areas of PMG (white arrows in many images) that appear most severe in the posterior frontal and perisylvian regions, but are symmetric in all patients shown. Midline sagittal images show mild (I) or moderate (M) cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH), as the bottom of the vermis (top white line in I and M) does not extend down to the level of the obex (bottom white line in I and M). The cisterna magna (double asterisks) is mildly prominent in one (M) and enlarged with an enlarged posterior fossa consistent with so-called mega-cisterna magna (I) in the other.

Deletion 4q21.21-q22.1

Our first patient (LR04-022a2) and an older half-sister with Dandy-Walker malformation were both conceived by in vitro fertilization; his sister does not share the 4q2 deletion. He was born following a pregnancy complicated by polyhydramnios and enlarged ventricles on prenatal ultrasound. His birth weight and head circumference were normal, and he had onset of seizures at 3 months. By 3 years, he had HYD managed with a shunt, and a non-communicating suprasellar cyst compressing the optic chiasm that was treated by fenestration of the cyst. His vision deteriorated following a shunt revision, but gradually improved to near normal. On exam at age 4.5 years, his OFC was 51 cm (50th centile). He had a triangular facial appearance with a relatively large head, prominent forehead, narrow nose, low-set and posteriorly rotated ears, flat philtrum and pointed chin. His balance was poor with probable ataxia, but he had minimal spasticity and normal reflexes. Abdominal ultrasound has not been done. Initial chromosome analysis was reported as normal, but array CGH detected a 9.3 Mb deletion in chromosome 4q21.1-q22.1 that was confirmed on repeat chromosome analysis.

The second child (LR07-256) with this deletion is a boy with severe developmental delay, hypotonia, normal head circumference, poor visual attention, conductive hearing loss, pale optic nerves, facial dysmorphism, atrial septal defect, and renal cysts. He also had a congenital juvenile-type granulosa cell tumor of the testes. Brain MRI in both boys (Fig 2) shows PMG in the mid- and posterior frontal plus perisylvian regions and mildly enlarged lateral ventricles. The MRI was done prior to development of HYD and shunt insertion in the first boy. The second did not have HYD. Both had mild to moderate CVH, and the first also had an enlarged posterior fossa consistent with so-called mega-cisterna magna.

Deletion 6q26-qter

We reviewed brain-imaging studies of six patients (Fig 3), and found extensive PMG that was sometimes difficult to appreciate in all of them. The PMG was most severe in the posterior frontal, perisylvian and temporal regions in three patients, and appeared limited to the temporal lobe in the other three. Other abnormalities included PNH of the trigones or temporal horns in four patients, HYD in three with less marked ventricular enlargement in the others, partial ACC in one and thin corpus callosum in three more, and CBLH in three patients. Autopsy in one boy (LP87-010a4) demonstrated extensive PMG, reduced volume of white matter, enlarged lateral ventricles, and cerebellar hypoplasia or atrophy.

Figure 3.

Brain images from four patients with deletion 6q26 including LR05-261 (A–D), LR00-218 (E–H), LP99-104a1 (I–L) and LP99-104a2 (M–P). These images show extensive areas of PMG (white arrows in many images) that is more difficult to appreciate than in other figures, but appears most severe in the temporal lobes and perisylvian regions. Midline sagittal images show thin and short corpus callosum (arrowheads in A and M) and CVH (arrowhead in E but also mildly small in A). Two patients had hydrocephalus (G and H, P).

Several patients were assigned breakpoints in 6q25.3 by cytogenetic analysis, with one (LR00-218) corrected to 6q26 by aCGH. The deletions ranged from 7.35 to 10.4 Mb in size. The sisters with the smallest deletion had fewer anomalies outside of the brain, but were otherwise similar [Eash et al., 2005]. One of the two sisters had HYD.

DISCUSSION

Our results and reports from the literature provide strong support for six PMG loci associated with pathogenic copy number variants, and weaker support for another five loci, which should be considered tentative from the data available (Table III). Several more loci associated with autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance are known as well.

Table III.

Polymicrogyria loci identified by cytogenetic analysis

| Locus | Mechanism | N | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP | LIT | |||

| Confirmed loci | ||||

| 1p36.3 | Del | 15 | 1 | [Ribeiro Mdo et al., 2007; Shapira et al., 1999] |

| 2p16.1-p23.1 | Dup | 2 | 0 | --- |

| 4q21.21-q22.1 | Del | 2 | 1 | [Nowaczyk et al., 1997] |

| 6q26-q27 | Del | 7 | 1 | [Curry et al., 2000; Eash et al., 2005; Salamanca-Gonez et al., 1975] |

| 21q21.3-q22.1* | Del | 2 | 4 | [Alkan et al., 2002; Chen et al., 1999; Yao et al., 2006] |

| 22q11.2 | Del | 21 | 11 | [Robin et al., 2006] |

| Possible loci | ||||

| 1q44 | Del | 1 | 2 | [Zollino et al., 2003; Zollino et al., 1992] |

| 2p15-p16.1 | Del | 0 | 2 | [Rajcan-Separovic et al., 2007] |

| 11q12-q13 | Dup | 0 | 1 | [Dupuy et al., 1999] |

| 13q14.1-q31.2 | Del | 0 | 1 | [Kogan et al., 2005] |

| 18p* | Del | 1 | 0 | --- |

Abbreviations: Del, deletion; Dup, duplication; LIT, number reported in literature; LP, number identified in our subject database; N, number of subjects.

Patients with combined del 18p and del 21q2 are included with the 21q locus.

Confirmed PMG loci

Deletion 1p36.3

Deletion 1p36.3 is the most commonly observed terminal deletion syndrome in humans [Heilstedt et al., 2003a]. The phenotype consists of developmental delay, mental retardation, hypotonia, speech delay, seizures, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart defects, hearing loss, eye anomalies and gastrointestinal problems. The most frequent dysmorphic features are flat nasal bridge, deep-set eyes, large anterior fontanel, pointed chin, microcephaly, clinodactyly and midface hypoplasia [Heilstedt et al., 2003a; Heilstedt et al., 2003b; Knight-Jones et al., 2000; Reish et al., 1995; Shapira et al., 1997; Slavotinek et al., 1999]. Previous mapping studies defined critical regions for hearing loss, moderate to severe mental retardation (D1S243 to D1S468) and seizures [Shapira et al., 1999; Wu et al., 1999], while brain imaging studies typically show abnormal white matter signal, especially on Flair sequences. Autopsy in one patient included in our series confirmed PMG [Shapira et al., 1999], as did a recent report of another patient [Ribeiro Mdo et al., 2007]. Our genotype-phenotype analysis revealed brain abnormalities on MRI in 60% of patients with deletion 1p36, with patchy signal abnormalities in white matter (leukoencephalopathy) and PMG being the most common (unpublished data). Other abnormalities found in more than one subject include generalized atrophy, prominent ventricles, delayed myelination, and thinning of the corpus callosum.

Duplication 2p16.1p23

The syndrome resulting from duplication of proximal 2p has not previously been delineated, although we found old reports of two patients [Monteleone et al., 1981; Yunis et al., 1979]. Adding these to our two patients (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), we reviewed clinical data on one girl with dup 2p16.1-p23.1, two boys with dup 2p13-p23 or 2p14-p23, and a newborn girl with dup 2p13-pter. From these data, the proximal 2p duplication syndrome is characterized by normal head size, mental retardation, and facial dysmorphism consisting of hypertelorism, broad nasal bridge and low-set malformed ears. The two boys with dup 2p13-p23 also had growth deficiency and genital abnormalities consisting of hypospadius and cryptorchidism. One boy (LR00-173) had corneal clouding. The girl with dup 2p13-pter had intrauterine growth retardation, similar facial changes plus cleft palate, skeletal anomalies and a complex heart malformation. Autopsy showed ovarian hypoplasia and dysplasia, as well as cerebellar hypoplasia with dysplastic foliar pattern and heterotopia that we presume were PNH [Monteleone et al., 1981]. The girl with the smallest deletion (LP99-112) has had seizures, behavior problems and sleep disturbances.

Deletion 4q21.21-q22.1

At least 10 children with deletion 4q21-q22 have been reported, with typical features including developmental delay, mental retardation, hypotonia, absolute or relative macrocephaly, frontal bossing, small nose, flat nasal bridge, malformed ears and small jaw. HYD was noted in 4 of 10 patients [Nowaczyk et al., 1997]. PMG has not been reported, but our review of the published brain MRI of Patient 1 from this report [Nowaczyk et al., 1997] suggests PMG in the perisylvian regions. Rare patients with deletion of this region have had polycystic kidney disease associated with deletion of PKD2 [Velinov et al., 2005], or infantile hepatocellular carcinoma [Terada et al., 2001].

The 9.3 Mb deletion in our patient LR04-022a2 contains 55 RefSeq genes including PKD2, while the deletion in LR07-256 is much larger, encompassing the entire region deleted in the first boy. The 9.3 Mb deletion overlaps with a region predisposing to hepatocellular carcinoma [Nishimura et al., 2006; Yeh et al., 2004], which when considered together with the granulosa cell tumor in LR07-256 supports the existence of one or more oncogenes in this region.

Deletion 6q26-qter

At least 30 patients with deletion 6q25-qter have been reported, most with deletion of the entire region. A review of 26 patients found mental retardation and facial dysmorphism in all, seizures in 88%, and short neck, retinal abnormalities, heart malformations and genital hypoplasia including cryptorchidism in about 50% each [Hopkin et al., 1997]. Three patients had HYD. The most consistent facial features were hypertelorism (30%), prominent nasal bridge (67%), epicanthal folds (66%), ear anomalies (88%,) and small jaw (72%). The retinal changes were variously described as abnormal retinal vessels, retinal pits or macular disorders such as hypopigmentation, hypoplasia or degeneration. Reports of about 17 patients with smaller deletions of distal 6q26-q27 describe less severe mental retardation but similar facial dysmorphism, mild MIC and short stature [Bertini et al., 2006; Eash et al., 2005]. None had short neck, retinal anomalies, heart malformations or genital hypoplasia. One child with a small 400 kb subtelomeric deletion had HYD, but also other atypical anomalies such as tracheo-esophageal fistula suggesting VATER syndrome, so we suspect that this child has a separate etiology for these abnormalities.

The PMG and PNH seen with deletion 6q26 (Fig 3) differs from other forms of PMG, somewhat resembling the posterior PNH and PMG syndrome that we recently described [Wieck et al., 2005]. Other reports provide limited information about the brain, although autopsy in a boy with ring chromosome 6 and presumed breakpoint in 6q26 demonstrated MIC, PMG and HYD [Salamanca-Gonez et al., 1975]. Another child had PNH with no further brain imaging data provided [Bertini et al., 2006]. Our data maps the critical region to a 7.35 Mb region between BAC RP11-57O22 and the 6q telomere (Table I), with penetrance unknown.

Deletion 21q22.1

Only a few individuals with partial deletions of chromosome 21q have been reported, with three distinct phenotypes. First, six individuals from two families with small centromeric deletions of 21q11.1-q21.2 had normal intelligence [Aviv et al., 1997; Korenberg et al., 1991], and another whose deletion extended to 21q21.3 had mild mental retardation [Roland et al., 1990]. Next, at least five patients with deletion 21q22.3 had holoprosencephaly [Aronson et al., 1987; Estabrooks et al., 1990; Muenke et al., 1995], and one individual with a small telomeric deletion of 21q22.3 had normal intelligence [Falik-Borenstein et al., 1992]. Another six patients have had proximal, interstitial or distal deletions involving bands 21q22.1-q22.2, all with multiple congenital anomalies [Ahlbom et al., 1996; Rethore and Dutrillaux 1973; Theodoropoulos et al., 1995; Yao et al., 2006].

A recent report of deletion 21q22.1-q22.2 listed many abnormalities including developmental delay, mental retardation, seizures, MIC and facial dysmorphism, as well as eye, heart, hand and feet, and genital anomalies with no further details provided [Yao et al., 2006]. Brain imaging in three patients was reported to show PMG, “pachygyria”, thin white matter, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and variable hypoplasia of the cerebellum [Yao et al., 2006]. Physical mapping in these three patients demonstrated a critical region of 8.4 Mb in 21q22.2-q22.3 flanked by the KCNJ6 and COL6A2 genes [Yao et al., 2006], a region that excludes the ITSN1 gene that was suggested as a PMG causative gene in abstracts [Chen et al., 1999]. However, the published brain imaging studies were too small to review and confirm the malformations.

Our patient with deletion 21q2 has severe mental retardation, microcephaly (−3 standard deviations at 11 years), prominent eyes, low-set and posteriorly rotated ears, coarse voice, clinodactyly, long slender hands and feet, mild spasticity and multiple contractures leading her to walk with a crouched posture. She began having drop seizures at 10 years. Brain MRI demonstrates symmetric perisylvian PMG involving only the perisylvian cortex as well as partial agenesis of the corpus callosum (Fig 4). Based on our observation of PMG in this girl and two boys with deletion of 18p plus 21q (see below), we hypothesize that deletion 21q2 is associated with PMG and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, but not with lissencephaly or “pachygyria”. Further studies will be needed to determine the critical region for PMG.

Deletion 18p11.2-pter plus deletion 21q22.1

We found one boy with deletion of both 18p and distal 21q, and unexpectedly found a report of another boy with the same karyotype [Alkan et al., 2002]. We obtained only limited data on our patient, while the reported boy had clinical features of both deletion 18p and deletion 21q. Brain imaging demonstrated perisylvian PMG in both patients; our patient also had mild CVH (Fig 4).

The PMG observed in these two children is open to at least two different interpretations. First, PMG could result from deletion 21q2, adding two more patients to the four described above. In this scenario, the PMG we report in a girl with deletion 18p might be coincidental. Alternatively, data from other PMG loci, especially 1p36.3 and 22q11.2, demonstrate incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. In this scenario, deletion of two putative PMG loci would be predicted to increase the penetrance and severity of the cortical malformation.

Deletion 22q11.2

The deletion 22q11.2 (DiGeorge or velocardiofacial) syndrome is a common disorder that is associated with many rare manifestations, including PMG in 12 reported patients [Bingham et al., 1998; Bird and Scambler 2000; Cramer et al., 1996; Ehara et al., 2003; Ghariani et al., 2002; Kawame et al., 2000; Koolen et al., 2004; Sztriha et al., 2004; Worthington et al., 2000]. We recently analyzed clinical data on 21 patients with PMG and deletion 22q11.2 from our subject database and 11 from the literature, finding perisylvian PMG associated with frequent asymmetry, a striking predisposition for the right hemisphere, and often mega-cisterna magna or mild CVH [Robin et al., 2006].

Possible PMG Loci

Deletion 1q44

At least 30 patients with deletion of 1q42q44 have been reported with constant but variable mental retardation, frequent seizures, and numerous congenital anomalies [van Bever et al., 2005]. The latter include facial dysmorphism especially upslanted palpebral fissures, ear anomalies, small jaw and cleft palate, heart malformations, abnormalities of the hands and feet, and genital anomalies such as hypospadius and cryptorchidism. The reported brain malformations include MIC in 25 of 27 and ACC in 22 of 25 affected individuals, both likely related to deletion of AKT3, as well as cerebellar hypoplasia or atrophy in 10 of 21 [Boland et al., 2007; Gentile et al., 2003; Hill et al., 2007; van Bever et al., 2005; van Bon et al., 2008].

The existence of a PMG causative gene in this region was first suggested by the report of PMG in two cousins with deletion 1q44 and duplication 12p13.3 resulting from the unbalanced state of a familial 1q;12p translocation [Zollino et al., 2003; Zollino et al., 1992]. Both boys with the unbalanced derivative 1 chromosome had PMG, and a subsequent paper reported a 14 cM deletion of the 1q telomere by FISH [Rossi et al., 2001], but we could not confirm the location of the YAC probe used. The deletion presumably includes AKT3 (5.5 Mb from the 1q telomere) due to the MIC and ACC. We previously reported probable perisylvian PMG in our patient LP94-079 (Supplementary Figure 1), but this girl also has an unbalanced duplication [Boland et al., 2007]. None of the remaining 20 patients with brain imaging findings reported had PMG [Boland et al., 2007; Hill et al., 2007; van Bon et al., 2008], leaving this putative locus in doubt.

Deletion 2p15-p16.1

Two children with a new deletion syndrome involving chromosome 2p were reported recently [Rajcan-Separovic et al., 2007]. Both of them had moderate to severe mental retardation with autistic features, poor attention, coordination and vision, MIC, dysmorphic appearance, camptodactyly and renal anomalies consisting of hydronephrosis or multicystic kidney. The facial features consist of flat occiput, widened inner canthal distance, small palpebral fissures, ptosis, long straight eyelashes, broad and high nasal root, prominent nasal tip, long smooth philtrum, and everted lower lips. Brain imaging demonstrated bilateral perisylvian cortical dysplasia (Patient 1) or “generally thickened cortex” (Patient 2) that probably represent perisylvian PMG, although no images were shown. BAC microarray analysis showed a critical region of 4.5 Mb between BACs RP11-81L7 and RP11-355B11.

Duplication 11q11-q12

Several patients with facial dysmorphism, atrioventricular canal and PMG associated with small duplications of 11q11-q12 were reported in an abstract several years ago [Dupuy et al., 1999]. No further information is available.

Deletion 13q14.1-q31.2

Interstitial deletions of proximal 13q that do not extend into 13q32 have most often been found with the retinoblastoma-mental retardation syndrome that results from heterozygous deletion of the RB1 gene in 13q14.2 and other unknown brain development genes [Baud et al., 1999; Brown et al., 1993]. About 70% of patients have severe mental retardation that correlates with the size and location of the deletion [Baud et al., 1999]. The typical facial abnormalities consist of a high broad forehead, prominent philtrum, and anteverted ear lobes. Patients with larger deletions, such as 13q14.12-q31.2, have a similar non-specific phenotype with added severe growth and mental retardation [Slavotinek and Lacbawan 2003], although brain imaging has not been reported.

One boy reported with deletion 13q14.1-q31.2 also had PMG [Kogan et al., 2005]. At 4 months, he had mental retardation, hypotonia, severe growth deficiency, facial dysmorphism, submucous cleft palate, hearing loss, bilateral inguinal hernias, and bilateral retinoblastomas. His facial abnormalities consisted of a triangular-shaped face, protuberant eyes, downslanting palpebral fissures, downturned mouth and small jaw. Brain imaging demonstrated severe and symmetric perisylvian PMG. Patients with more distal deletions involving 13q32 have had severe brain malformations including holoprosencephaly and Dandy-Walker malformation, but not polymicrogyria [Alanay et al., 2005; Marcorelles et al., 2002; McCormack et al., 2002].

Deletion 18p

More than 150 patients with deletion 18p have been reported [Wester et al., 2006]. Typical features include mild to moderate mental retardation, short stature and facial dysmorphism, with less frequent malformations of the brain, heart, limbs and genitalia. Facial changes consist of ptosis, broad flat nose, hypertelorism, large protruding ears and small jaw. Other problems include strabismus, hypotonia, slow movements, autoimmune disorders, and pituitary insufficiency. A few have had holoprosencephaly [Overhauser et al., 1995], which may be associated with a single central incisor and pituitary insufficiency. One patient with Dandy-Walker malformation and hydrocephalus was recently reported but no images were provided [Wester et al., 2006]. Overall, brain-imaging studies have only rarely been described.

We identified a single patient with deletion 18p syndrome who has unilateral right perisylvian PMG (Fig 4). This girl has a deletion of almost the entire short arm, so we cannot refine the location of the putative PMG gene. Penetrance is probably low as deletions of 18p are not rare, and we found no reports of this association. The only other supportive data for this locus are the two patients with combined del 18p and dup 21q22.1, which we think are more likely due to the chromosome 21q deletion with deletion 18p as a possible modifier locus.

The genetic basis of polymicrogyria

Polymicrogyria genes

Reports to date have identified three human genes associated with PMG including RAB3GAP in 2q21.3, TBR2 in 3p21, KIAA1279 in 10q22.1 and PAX6 in 11p13. The most interesting so far involve the interacting genes PAX6 and TBR2 (EOMES). High-resolution brain imaging in 2 of 24 patients with aniridia due to heterozygous PAX6 mutations had focal and apparently unilateral temporal lobe PMG, in addition to hypoplasia or absence of the pineal gland and anterior commissure [Mitchell et al., 2003; Sisodiya et al., 2001]. More importantly, an infant who was a compound heterozygote for two different mutations of PAX6 had a severe brain malformation consisting of ACC and extensive PMG [Glaser et al., 1994]. Studies in mouse mutants have shown that Pax6 is involved in dorsoventral patterning of the telencephalon [Stoykova et al., 2000], specification of neuronal identity [Briscoe et al., 1999], radial glia differentiation and intermediate progenitor cell division [Englund et al., 2005; Gotz et al., 1998], neuronal migration [Brunjes et al., 1998; Talamillo et al., 2003], and cortico-thalamic and thalamo-cortical pathfinding [Hevner et al., 2002]. Loss of regulation of some or all of these functions might leads to PMG, and Pax6−/− mutants may be the most appropriate animal models for study currently available. Importantly, a boy with homozygous mutation of TBR2 had MIC, ACC, PMG and persistent unexplained fevers [Baala et al., 2007]. The TBR2 protein functions immediately downstream of PAX6, and regulates intermediate progenitor cell division [Englund et al., 2005]. This suggests that deficiency or altered fate of neurons derived from intermediate progenitor cell division may be one cause of PMG.

Mutations of RAB3GAP were identified in 12 of 18 probands with Warburg Micro syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder manifest by MIC, frontal PMG, eye malformations and genital hypoplasia [Aligianis et al., 2005; Graham et al., 2004]. The protein regulates the Rab3 pathway that functions in exocytic release of hormones, neurotransmitters and possibly trophic factors, but the mechanism by which this leads to PMG is not clear. Mutations of KIAA1279 were found in patients with Goldberg-Shprintzen syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder with MIC, mental retardation and Hirschsprung disease (absence of ganglion cells in the wall of the colon) as the major manifestations [Brooks et al., 2005; Brooks et al., 1999; Goldberg and Shprintzen 1981; Hurst et al., 1988]. A recent report recognized bilateral diffuse PMG as part of the phenotype. The gene encodes a protein with two tetratrico peptide repeats although little is yet known about gene or protein function [Brooks et al., 2005].

Polymicrogyria syndromes

PMG occurs as a major (and probably constant) component of several multiple congenital anomaly – mental retardation syndromes including Aicardi, oculo-cerebro-cutaneous (Delleman) and Warburg Micro syndromes [Billette de Villemeur et al., 1992; Brooks et al., 2005; Ferrer et al., 1986; Graham et al., 2004; Moog et al., 2005; Nassogne et al., 2000; Pascual-Castroviejo et al., 2005], and occasionally in Adams-Oliver syndrome [Amor et al., 2000]. Given the reduced penetrance of PMG found in these deletion syndromes, we expect the list of syndromes occasionally associated with PMG to expand, as demonstrated by a recent report for Aarskog-Scott syndrome [Bottani et al., 2007].

Conclusions

Despite numerous clinical and pathological studies, we still have very limited understanding of the causes of PMG, as both extrinsic (see Introduction) and genetic causes are known. Our data provides the first detailed documentation for PMG loci across the human genome, which we anticipate will serve as the basis for ongoing efforts to identify more PMG causal genes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Brain CT images from a girl with deletion 1q44 (A–D, LP94-079) show an open sylvian fissure, reduced sulcation and mildly thick cortex (white arrows in each image) that suggest a cortical malformation. The lowest image demonstrates severe CVH based on lack of any vermis at the level of the midbrain (A), and the highest image shows a small occipital cephalocele (arrowhead in D). Images A, B and D are re-printed from Boland et al.,, 2007.

Supplementary Figure 2. FISH in patient LR00-173. Hybridization with BAC probe CTB-6J9 from 2p16.1 labeled in orange (white arrows) shows one signal on the normal chromosome 2 homolog, but two signals on the duplicated homolog. This BAC contains marker AFMB304YH1. Control probe RP11-113N17 from 2p12 labeled in aqua is not in the duplicated region and shows only one signal on each homolog.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the families of all of these children for sharing their medical information with us. This work was supported by grants from The University of Chicago Brain Research Foundation to Dr. Dobyns, and from the National Institutes of Health to Drs. Dobyns (1P01-NS039404 and 1R01-NS050375) and Shaffer (P01-HD39420).

References

- Ahlbom BE, Sidenvall R, Anneren G. Deletion of chromosome 21 in a girl with congenital hypothyroidism and mild mental retardation. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:501–505. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960823)64:3<501::AID-AJMG11>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanay Y, Aktas D, Utine E, Talim B, Onderoglu L, Caglar M, Tuncbilek E. Is Dandy-Walker malformation associated with “distal 13q deletion syndrome”? Findings in a fetus supporting previous observations. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2005;136A:265–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aligianis IA, Johnson CA, Gissen P, Chen D, Hampshire D, Hoffmann K, Maina EN, Morgan NV, Tee L, Morton J, et al. Mutations of the catalytic subunit of RAB3GAP cause Warburg Micro syndrome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:221–223. doi: 10.1038/ng1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkan M, Ramelli GP, Hirsiger H, Keser I, Remonda L, Buhler EM, Moser H. Presumptive monosomy 21 with neuronal migration disorder re-diagnosed as de novo unbalanced translocation t(18p;21q) by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Genet Couns. 2002;13(2):151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor DJ, Leventer RJ, Hayllar S, Bankier A. Polymicrogyria associated with scalp and limb defects: variant of Adams-Oliver syndrome [In Process Citation] Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:328–334. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000814)93:4<328::aid-ajmg13>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson DC, Jansweijer MC, Hoovers JM, Barth PG. A male infant with holoprosencephaly, associated with ring chromosome 21. Clin Genet. 1987;31:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb02766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv H, Lieber C, Yenamandra A, Desposito F. Familial transmission of a deletion of chromosome 21 derived from a translocation between chromosome 21 and an inverted chromosome 22. Am J Med Genet. 1997;70:399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baala L, Briault S, Etchevers HC, Laumonnier F, Natiq A, Amiel J, Boddaert N, Picard C, Sbiti A, Asermouh A, et al. Homozygous silencing of T-box transcription factor EOMES leads to microcephaly with polymicrogyria and corpus callosum agenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:454–456. doi: 10.1038/ng1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Hevner R, Guerrini R. Syndromes of bilateral symmetrical polymicrogyria. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1814–1821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Lindan CE. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection of the brain: imaging analysis and embryologic considerations. AJNR. 1994;15:703–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MT, Scheffer A, Ben-Dor A, Sampas N, Lipson D, Kincaid R, Tsang P, Curry B, Baird K, Meltzer PS, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization using oligonucleotide microarrays and total genomic DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17765–17770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407979101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth PG. Migrational disorders of the brain. Curr Opin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;5:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth PG, van der Harten JJ. Parabiotic twin syndrome with topical isocortical disruption and gastroschisis. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;67:345–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00687825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei F, Gavaret M, Dravet C, Guerrini R. Familial epilepsy with unilateral and bilateral malformations of cortical development. Epilepsia. 1999;40:47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud O, Cormier-Daire V, Lyonnet S, Desjardins L, Turleau C, Doz F. Dysmorphic phenotype and neurological impairment in 22 retinoblastoma patients with constitutional cytogenetic 13q deletion. Clin Genet. 1999;55:478–482. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini V, De Vito G, Costa R, Simi P, Valetto A. Isolated 6q terminal deletions: an emerging new syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140A:74–81. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billette de Villemeur T, Chiron C, Robain O. Unlayered polymicrogyria and agenesis of the corpus callosum: a relevant association? Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1992;83:265–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00296788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham PM, Lynch D, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai E. Polymicrogyria in chromosome 22 deletion syndrome. Neurology. 1998;51:1500–1502. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird LM, Scambler P. Cortical dysgenesis in 2 patients with chromosome 22q11 deletion. Clin Genet. 2000;58:64–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.580111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E, Clayton-Smith J, Woo VG, McKee S, Manson FD, Medne L, Zackai E, Swanson EA, Fitzpatrick D, Millen KJ, Sherr EH, Dobyns WB, Black GC. Mapping of deletion and translocation breakpoints in 1q44 implicates the serine/threonine kinase AKT3 in postnatal microcephaly and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:292–303. doi: 10.1086/519999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti R, Triulzi F, Zucca C, Piccinelli P, Balottin U, Carrozzo R, Guerrini R. Bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria in three generations. Neurology. 1999;52:1910–1913. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottani A, Orrico A, Galli L, Karam O, Haenggeli CA, Ferey S, Conrad B. Unilateral focal polymicrogyria in a patient with classical Aarskog-Scott syndrome due to a novel missense mutation in an evolutionary conserved RhoGEF domain of the faciogenital dysplasia gene FGD1. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2007;143A:2334–2338. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresler NC. Arch Psychiat Nervenkr. 1899;31:566–XXX. Title Unavailable. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Sussel L, Serup P, Hartigan-O’Connor D, Jessell TM, Rubenstein JL, Ericson J. Homeobox gene Nkx2.2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature. 1999;398:622–627. doi: 10.1038/19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AS, Bertoli-Avella AM, Burzynski GM, Breedveld GJ, Osinga J, Boven LG, Hurst JA, Mancini GM, Lequin MH, de Coo RF, Matera I, de Graaff E, Meijers C, Willems PJ, Tibboel D, Oostra BA, Hofstra RM. Homozygous nonsense mutations in KIAA1279 are associated with malformations of the central and enteric nervous systems. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:120–126. doi: 10.1086/431244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AS, Breuning MH, Osinga J, vd Smagt JJ, Catsman CE, Buys CH, Meijers C, Hofstra RM. A consanguineous family with Hirschsprung disease, microcephaly, and mental retardation (Goldberg-Shprintzen syndrome) J Med Genet. 1999;36:485–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Gersen S, Anyane-Yeboa K, Warburton D. Preliminary definition of a “critical region” of chromosome 13 in q32: report of 14 cases with 13q deletions and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:52–59. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunjes PC, Fisher M, Grainger R. The small-eye mutation results in abnormalities in the lateral cortical migratory stream. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;110:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo RH, Cersosimo RO, Mazza E, Fejerman N. Focal polymicrogyria in mother and son. Brain Dev. 2000;22:336–339. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X-N, Huynh DP, Huo Y, Shi Z-Y, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Pulst SM, Korenberg JR. Chromosome 21 deletion and cortical dysgenesis: Intersectin (ITSN) is expressed in subsets of post-mitotic neurons in the developing brain. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(4 supp):A76. (abstract #402) [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JK. High throughput determination of gains and losses of genetic material using high resolution BAC arrays and comparative genomic hybridization. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2004;7:587–596. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JK, Wang YD, Head K, Conroy J, McQuaid D, Nowak NJ. Identification and characterisation of constitutional chromosome abnormalities using arrays of bacterial artificial chromosomes. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:860–865. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Schaefer PW, Krishnamoorthy KS. Microgyria in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery in a patient with DiGeorge syndrome. J Child Neurol. 1996;11:494–497. doi: 10.1177/088307389601100619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crome L. Microgyria. Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 1952;64:479–495. doi: 10.1002/path.1700640308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry CJ, Lammer EJ, Nelson V, Shaw GM. Schizencephaly: heterogeneous etiologies in a population of 4 million California births. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2005;137A:181–189. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry CJ, Triesman T, Roeder E, Drumheller T. Hydrocephalus, microcephaly, and neuronal migrational abnormalities: a 15-year mystery explained by a 6q deletion. Proc Greenwood Genet Center. 2000;19:78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dobyns WB, Barkovich AJ. Microcephaly with simplified gyral pattern (oligogyric microcephaly) and microlissencephaly: reply. Neuropediatr. 1999;30:104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy O, Husson I, Wirth J, Wiss J, Nessmann C, Evrard P, Eydoux P. Pachygyria and polymicrogyria, cranio-facial dysmorphism and atrio-ventricular canal resulting from a duplication of the proximal region of chromosome 11q (11q11-11q12) Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(4 supp):A161. (#878) [Google Scholar]

- Eash D, Waggoner D, Chung J, Stevenson D, Martin CL. Calibration of 6q subtelomere deletions to define genotype/phenotype correlations. Clin Genet. 2005;67:396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehara H, Maegaki Y, Takeshita K. Pachygyria and polymicrogyria in 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2003;117A:80–82. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Fink A, Lau C, Pham D, Daza RA, Bulfone A, Kowalczyk T, Hevner RF. Pax6, Tbr2, and Tbr1 are expressed sequentially by radial glia, intermediate progenitor cells, and postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:247–251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks LL, Rao KW, Donahue RP, Aylsworth AS. Holoprosencephaly in an infant with a minute deletion of chromosome 21(q22.3) Am J Med Genet. 1990;36:306–309. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320360312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falik-Borenstein TC, Pribyl TM, Pulst SM, Van Dyke DL, Weiss L, Chu ML, Kraus J, Marshak D, Korenberg JR. Stable ring chromosome 21: molecular and clinical definition of the lesion. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(1):22–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I. A Golgi analysis of unlayered polymicrogyria. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;65(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00689830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Cusi MV, Liarte A, Campistol J. A golgi study of the polymicrogyric cortex in Aicardi syndrome. Brain Dev. 1986;8:518–525. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(86)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie CD, Jackson GD, Giannakodimos S, Panayiotopoulos CP. Posterior agyria-pachygyria with polymicrogyria: evidence for an inherited neuronal migration disorder. Neurology. 1995;45:150–153. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile M, Di Carlo A, Volpe P, Pansini A, Nanna P, Valenzano MC, Buonadonna AL. FISH and cytogenetic characterization of a terminal chromosome 1q deletion: clinical case report and phenotypic implications. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2003;117A:251–254. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghariani S, Dahan K, Saint-Martin C, Kadhim H, Morsomme F, Moniotte S, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Sebire G. Polymicrogyria in chromosome 22q11 deletion syndrome. Europ J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6:73–77. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2001.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F, David A, Edery P, Sigaudy S, Bonneau D, Cormier-Daire V, Philip N. Macrocephaly-cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: seven cases including two with unusual cerebral manifestations. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;126A:99–103. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser T, Jepeal L, Edwards JG, Young SR, Favor J, Maas RL. PAX6 gene dosage effect in a family with congenital cataracts, aniridia, anophthalmia and central nervous system defects. Nat Genet. 1994;7:463–471. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlich-Ratmann G, Baethmann M, Lorenz P, Gartner J, Goebel HH, Engelbrecht V, Christen HJ, Lenard HG, Voit T. Megalencephaly, mega corpus callosum, and complete lack of motor development: a previously undescribed syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:161–167. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980923)79:3<161::aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RB, Shprintzen RJ. Hirschsprung megacolon and cleft palate in two sibs. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1981;1:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz M, Stoykova A, Gruss P. Pax6 controls radial glia differentiation in the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Jr, Hennekam R, Dobyns WB, Roeder E, Busch D. MICRO syndrome: an entity distinct from COFS syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;128A:235–45. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro MM, Andermann E, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB, Kuzniecky R, Silver K, Van Bogaert P, Gillain C, David P, Ambrosetto G, et al. Familial perisylvian polymicrogyria: a new familial syndrome of cortical maldevelopment. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Barkovich AJ, Sztriha L, Dobyns WB. Bilateral frontal polymicrogyria: a newly recognized brain malformation syndrome [In Process Citation] Neurology. 2000;54:909–913. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Dubeau F, Dulac O, Barkovich AJ, Kuzniecky R, Fett C, Jones-Gotman M, Canapicchi R, Cross H, Fish D, et al. Bilateral parasagittal parietooccipital polymicrogyria and epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:65–73. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Genton P, Bureau M, Parmeggiani A, Salas-Puig X, Santucci M, Bonanni P, Ambrosetto G, Dravet C. Multilobar polymicrogyria, intractable drop attack seizures, and sleep- related electrical status epilepticus. Neurology. 1998;51:504–512. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward JC, Titelbaum DS, Clancy RR, Zimmerman RA. Lissencephaly-pachygyria associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Child Neurol. 1991;6:109–114. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilstedt HA, Ballif BC, Howard LA, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG. Population data suggest that deletions of 1p36 are a relatively common chromosome abnormality. Clin Genet. 2003a;64:310–316. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilstedt HA, Ballif BC, Howard LA, Lewis RA, Stal S, Kashork CD, Bacino CA, Shapira SK, Shaffer LG. Physical map of 1p36, placement of breakpoints in monosomy 1p36, and clinical characterization of the syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003b;72:1200–1212. doi: 10.1086/375179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Miyashita-Lin E, Rubenstein JL. Cortical and thalamic axon pathfinding defects in Tbr1, Gbx2, and Pax6 mutant mice: evidence that cortical and thalamic axons interact and guide each other. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:8–17. doi: 10.1002/cne.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilburger AC, Willis JK, Bouldin E, Henderson-Tilton A. Familial schizencephaly. Brain Dev. 1993;15:234–236. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(93)90072-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AD, Chang BS, Hill RS, Garraway LA, Bodell A, Sellers WR, Walsh CA. A 2-Mb critical region implicated in the microcephaly associated with terminal 1q deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2007;143A:1692–1698. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin RJ, Schorry E, Bofinger M, Milatovich A, Stern HJ, Jayne C, Saal HM. New insights into the phenotypes of 6q deletions. Am J Med Genet. 1997;70:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JA, Markiewicz M, Kumar D, Brett EM. Unknown syndrome: Hirschsprung’s disease, microcephaly, and iris coloboma: a new syndrome of defective neuronal migration. J Med Genet. 1988;25:494–497. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.7.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannetti P, Nigro G, Spalice A, Faiella A, Boncinelli E. Cytomegalovirus infection and schizencephaly: case reports. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:123–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawame H, Kurosawa K, Akatsuka A, Ochiai Y, Mizuno K. Polymicrogyria is an uncommon manifestation in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome [letter] Am J Med Genet. 2000;94:77–78. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000904)94:1<77::aid-ajmg16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight-Jones E, Knight S, Heussler H, Regan R, Flint J, Martin K. Neurodevelopmental profile of a new dysmorphic syndrome associated with submicroscopic partial deletion of 1p36.3. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:201–206. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JM, Egelhoff JC, Saal HM. Interstitial deletion of 13q associated with polymicrogyria. American Society of Human Genetics 55th Annual Meeting; Salt Lake City, UT: American Society of Human Genetics; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolen DA, Veltman JA, Renier WO, Droog RP, van Kessel AG, de Vries BB. Chromosome 22q11 deletion and pachygyria characterized by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;131A:322–324. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenberg JR, Kalousek DK, Anneren G, Pulst SM, Hall JG, Epstein CJ, Cox DR. Deletion of chromosome 21 and normal intelligence: molecular definition of the lesion. Hum Genet. 1991;87:112–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00204163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzniecky RI, Andermann F, Guerrini R. The congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome: study of 31 patients. The congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome multicenter collaborative study. Lancet. 1993;341:608–612. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90363-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventer RJ. Polymicrogyria and related disorders of cortical development: a clinical, imaging and genetic study. Melbourne, Australia: The University of Melbourne; 2007. p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- Leventer RJ, Lese CM, Cardoso C, Roseberry J, Weiss A, Stoodley N, Pilz DT, Villard L, Nguyen K, Clark GD, et al. A study of 220 patients with polymicrogyria delineates distinct phenotypes and reveals genetic loci on chromosomes 1p, 2p, 6q, 21q and 22q (abstract) Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(4 supp):177. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DN, Fisher MA, Caviness VS., Jr Porencephaly with microgyria: a pathologic study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1974;29:99–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00684769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcorelles P, Loget P, Fallet-Bianco C, Roume J, Encha-Razavi F, Delezoide AL. Unusual variant of holoprosencephaly in monosomy 13q. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:170–178. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack WM, Jr, Shen JJ, Curry SM, Berend SA, Kashork C, Pinar H, Potocki L, Bejjani BA. Partial deletions of the long arm of chromosome 13 associated with holoprosencephaly and the Dandy-Walker malformation. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:384–389. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaa G, Dodge NN, Glass I, Day C, Gripp K, Nicholson L, Straub V, Voit T, Dobyns WB. Megalencephaly and perisylvian polymicrogyria with postaxial polydactyly and hydrocephalus: a rare brain malformation syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Neuropediatrics. 2004;35:353–359. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TN, Free SL, Williamson KA, Stevens JM, Churchill AJ, Hanson IM, Shorvon SD, Moore AT, van Heyningen V, Sisodiya SM. Polymicrogyria and absence of pineal gland due to PAX6 mutation. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:658–663. doi: 10.1002/ana.10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone PL, Blair JD, Graviss ER, Chen SC, Salvador A, Grzegocki JA, Monteleone JA. De novo partial 2p duplication with postmortem description. Am J Med Genet. 1981;10:55–64. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moog U, Jones MC, Bird LM, Dobyns WB. Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome: the brain malformation defines a core phenotype. J Med Genet. 2005;42:913–921. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CA, Toriello HV, Abuelo DN, Bull MJ, Curyr CJR, Hall BD, Higgins JV, Stevens CA, Twersky S, Weksberg R, et al. Macrocephaly-cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita syndrome: a distinct disorder with developmental delay and connective tissue abnormality. Am J Med Genet. 1997;70:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenke M, Bone LJ, Mitchell HF, Hart I, Walton K, Hall-Johnson K, Ippel EF, Dietz-Band J, Kvaloy K, Fan CM, et al. Physical mapping of the holoprosencephaly critical region in 21q22.3, exclusion of SIM2 as a candidate gene for holoprosencephaly, and mapping of SIM2 to a region of chromosome 21 important for Down syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1074–1079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassogne MC, Henrot B, Saint-Martin C, Kadhim H, Dobyns WB, Sebire G. Polymicrogyria and motor neuropathy in Micro syndrome [In Process Citation] Neuropediatrics. 2000;31:218–221. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Nishida N, Komeda T, Fukuda Y, Ikai I, Yamaoka Y, Nakao K. Genome-wide semiquantitative microsatellite analysis of human hepatocellular carcinoma: discrete mapping of smallest region of overlap of recurrent chromosomal gains and losses. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;167:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MG. Bilateral encephaloclastic lesions in a 26 week gestation fetus: effect on neuroblast migration. Can J Neurol Sci. 1980;7:191–194. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100023180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowaczyk MJ, Teshima IE, Siegel-Bartelt J, Clarke JT. Deletion 4q21/4q22 syndrome: two patients with de novo 4q21.3q23 and 4q13.2q23 deletions. Am J Med Genet. 1997;69:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Nanya Y, Yamamoto G. Genome-wide Copy Number Analysis on GeneChip(R) Platform Using Copy Number Analyzer for Affymetrix GeneChip 2.0 Software. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;396:185–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-515-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overhauser J, Mitchell HF, Zackai EH, Tick DB, Rojas K, Muenke M. Physical mapping of the holoprosencephaly critical region in 18p11.3. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1080–1085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, Lapunzina P. Oculocerebrocutaneous (Delleman) syndrome: report of two cases. Neuropediatrics. 2005;36:50–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajcan-Separovic E, Harvard C, Liu X, McGillivray B, Hall JG, Qiao Y, Hurlburt J, Hildebrand J, Mickelson EC, Holden JJ, et al. Clinical and molecular cytogenetic characterisation of a newly recognised microdeletion syndrome involving 2p15-16.1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:269–276. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reish O, Berry SA, Hirsch B. Partial monosomy of chromosome 1p36.3: characterization of the critical region and delineation of a syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1995;59:467–745. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rethore MO, Dutrillaux B. Translocation 46, XX, t(15; 21) (q13; q22,1) in the mother of 2 children with partial trisomy 15 and monosomy 21. Ann Genet. 1973;16:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Mdo C, Gama de Sousa S, Freitas MM, Carrilho I, Fernandes I. Bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria and chromosome 1 anomaly. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:418–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin NH, Taylor CJ, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Bingham P, Collins KJ, Earl D, Gill D, Granata T, Guerrini R, Katz N, Kimonis V, Lin JP, Lynch DR, Mohammed SN, Massey RF, McDonald M, Rogers RC, Splitt M, Stevens CA, Tischkowitz MD, Stoodley N, Leventer RJ, Pilz DT, Dobyns WB. Polymicrogyria and deletion 22q11.2 syndrome: Window to the etiology of a common cortical malformation. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140A:2416–2425. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland B, Cox DM, Hoar DI, Fowlow SB, Robertson AS. A familial interstitial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 21. Clin Genet. 1990;37:423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi E, Piccini F, Zollino M, Neri G, Caselli D, Tenconi R, Castellan C, Carrozzo R, Danesino C, Zuffardi O, et al. Cryptic telomeric rearrangements in subjects with mental retardation associated with dysmorphism and congenital malformations. J Med Genet. 2001;38:417–420. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca-Gonez F, Nava S, Armendares S. Ring chromosome 6 in a malformed boy. Clin Genet. 1975;8:370–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1975.tb01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer LG, McCaskill C, Han JY, Choo KH, Cutillo DM, Donnenfeld AE, Weiss L, Van Dyke DL. Molecular characterization of de novo secondary trisomy 13. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:968–974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira SK, Heilstedt HA, Starkey DE, Burgess DL, Chedrawi AK, Anderson AE, Tharp B, Carrol CL, Armstrong D, Wu Y-Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characterization of epilepsy in patients with monosomy 1p36 and the search for candidate genes (abstract 564) Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(4 supp):A107. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira SK, McCaskill C, Northrup H, Spikes AS, Elder FF, Sutton VR, Korenberg JR, Greenberg F, Shaffer LG. Chromosome 1p36 deletions: the clinical phenotype and molecular characterization of a common newly delineated syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:642–650. doi: 10.1086/515520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisodiya SM, Free SL, Williamson KA, Mitchell TN, Willis C, Stevens JM, Kendall BE, Shorvon SD, Hanson IM, Moore AT, van Heyningen V Epilepsy Research Group, University Department of Clinical Neurology. PAX6 haploinsufficiency causes cerebral malformation and olfactory dysfunction in humans. Nat Genet. 2001;28:214–216. doi: 10.1038/90042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavotinek A, Shaffer LG, Shapira SK. Monosomy 1p36. J Med Genet. 1999;36:657–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavotinek AM, Lacbawan F. Large interstitial deletion of chromosome 13q and severe short stature: clinical report and review of the literature. Clin Dysmorphol. 2003;12:195–196. doi: 10.1097/01.mcd.0000072160.33788.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoykova A, Treichel D, Hallonet M, Gruss P. Pax6 modulates the dorsoventral patterning of the mammalian telencephalon. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8042–8050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08042.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztriha L, Guerrini R, Harding B, Stewart F, Chelloug N, Johansen JG. Clinical, MRI, and pathological features of polymicrogyria in chromosome 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;127A:313–317. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talamillo A, Quinn JC, Collinson JM, Caric D, Price DJ, West JD, Hill RE. Pax6 regulates regional development and neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex. Dev Biol. 2003;255:151–163. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Imoto I, Nagai H, Suwa K, Momoi M, Tajiri T, Onda M, Inazawa J, Emi M. An 8-cM interstitial deletion on 4q21-q22 in DNA from an infant with hepatoblastoma overlaps with a commonly deleted region in adult liver cancers. Am J Med Genet. 2001;103:176–180. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoropoulos DS, Cowan JM, Elias ER, Cole C. Physical findings in 21q22 deletion suggest critical region for 21q- phenotype in q22. Am J Med Genet. 1995;59:161–163. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bever Y, Rooms L, Laridon A, Reyniers E, van Luijk R, Scheers S, Wauters J, Kooy RF. Clinical report of a pure subtelomeric 1qter deletion in a boy with mental retardation and multiple anomalies adds further evidence for a specific phenotype. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2005;135A:91–95. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bon BW, Koolen DA, Borgatti R, Magee A, Garcia-Minaur S, Rooms L, Reardon W, Zollino M, Bonaglia MC, Degregori M, Novara F, Grasso R, Ciccone R, van Duyvenvoorde HA, Aalbers AM, Guerrini R, Fazzi E, Nillesen WM, McCullough S, Kant SG, Marcelis CL, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, Smeets D, Sistermans EA, Wit JM, Hamel BC, Brunner HG, Kooy F, Zuffardi O, de Vries BB. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics of 1qter Syndrome: Delineating a Critical Region for corpus callosum agenesis/hypogenesis. J Med Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055830. (ePub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velinov M, Kupferman J, Gu H, Macera MJ, Babu A, Jenkins EC, Kupchik G. Polycystic kidneys and del (4)(q21.1q21.3): further delineation of a distinct phenotype. Eur J Med Genet. 2005;48:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester U, Bondeson ML, Edeby C, Anneren G. Clinical and molecular characterization of individuals with 18p deletion: a genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140A:1164–1171. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieck G, Leventer RJ, Squier WM, Jansen A, Andermann E, Dubeau F, Ramazzotti A, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB. Periventricular nodular heterotopia with overlying polymicrogyria. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 12):2811–2821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington S, Turner A, Elber J, Andrews PI. 22q11 deletion and polymicrogyria--cause or coincidence? [In Process Citation] Clin Dysmorphol. 2000;9:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200009030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YQ, Heilstedt HA, Bedell JA, May KM, Starkey DE, McPherson JD, Shapira SK, Shaffer LG. Molecular refinement of the 1p36 deletion syndrome reveals size diversity and a preponderance of maternally derived deletions. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:313–321. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]