Abstract

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) plays key roles in the metabolism of glutathione. Previous studies have shown that GGT expression was increased by oxidants, but the mechanism remains unclear. In the present study, the effects of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), an electrophilic end product of lipid peroxidation, on GGT expression were investigated in rat lung epithelial type II (L2) cells. We demonstrated that HNE increased GGT activity and mRNA content in both time- and dose-dependent manners. Actinomycin D, an RNA transcription inhibitor, blocked HNE-stimulated increase in GGT mRNA, suggesting transcriptional regulation of GGT mRNA by HNE. Of the seven GGT mRNA transcripts known to be produced from the single rat GGT gene, we found that types I, II, and V-2 were constitutively expressed in L2 cells, but only types I and V-2 were increased by HNE. PD98059 and SB203580, relatively specific inhibitors of the ERK and the p38MAPK kinase pathway, respectively, significantly attenuated HNE induction of both GGT activity and mRNA content. In contrast, studies with JNK inhibitor I, a cell-permeable peptide, indicated that JNK was not involved in the GGT induction by HNE. We also found that GGT induction by HNE could be completely blocked by a cocktail of PD98059 and SB203580, suggesting a combined effect of ERK and p38MAPK pathways in HNE-mediated GGT induction. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that HNE increased GGT expression in rat alveolar type II cells and that the induction of GGT by HNE was mediated through activation of the ERK and p38MAPK pathways.

Keywords: Glutathione, GGT, HNE, MAPK, Oxidative stress, Free radicals

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-glutamyl transferase; GGT), a glycosylated enzyme located on the outer surface of the plasma membrane, catalyzes the transfer of the γ-glutamyl moiety from peptide donors such as glutathione (GSH) to a variety of acceptors, including amino acids, dipeptides, and H2O [1]. The breakdown of extracellular GSH provides cysteine, the rate-limiting amino acid for glutathione synthesis. As such, GGT plays a key role in GSH and cysteine homeostasis [2–5]. GGT also catalyzes the metabolism of natural biomolecules such as leukotriene C4, xenobiotics, and carcinogens and chemotherapeutic drugs after their conjugation with GSH [6]. GSH conjugates are cleaved by GGT as the initial step of their conversion to mercapturic acids, a process that is usually considered a detoxification pathway [7,8].

GGT is mainly expressed in epithelial cells with absorptive or secretive functions, e.g., renal proximal tubule cells and bile duct epithelial cells [9]. In the lung, GGT is mainly expressed in Clara cells and type II epithelial cells, whereas other alveolar space cells, including alveolar macrophages, have undetectable GGT mRNA and protein although the macrophage can adsorb the enzyme from the extracellular fluid [10,11]. The ELF GSH content has been reported to be as high as 400 μM in humans [12] and 2 mM in rats [13], which is about 100-fold higher concentration than in the plasma. This alveolar GSH pool provides not only an extracellular antioxidant defense, but also cysteine for alveolar space cells after the cleavage of GSH by GGT followed by cysteinylglycine cleavage by dipeptidases found on cell surfaces. GGT deficiency alters the GSH/GSSG ratio and decreases the content of cysteine and GSH in alveolar space cells, which show signs of oxidative stress even under normal oxygen concentration [5,14]. GGT-deficient mice are more susceptible to pulmonary oxygen toxicity than wild-type mice, demonstrating the important roles of GGT in maintaining antioxidant function in the lung [4,5,14–16].

Many physiological and pathological factors regulate GGT expression. GGT expression is increased in whole lung after birth [10], but is decreased in adult liver compared to fetal liver [17]. GGT activity is increased in certain liver diseases, after stroke, in tumor tissues, and in other pathologies [18–23]. Many substances, especially those that generate reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) and/or perturb the redox balance, such as aflatoxin B1, NO2, redox cycling quinones, and alcohol, can increase GGT expression in various cells and tissues [24–30]. As an essential component of the cellular antioxidant defense system, upregulation of GGT upon oxidative stress facilitates de novo GSH synthesis and the metabolism of GSH S-conjugates, which renders cells more resistant to further oxidative challenge. Despite these important findings, the mechanism of GGT regulation in response to oxidative stress remains unclear.

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), an end product of lipid peroxidation, is both a toxic electrophile that forms adducts with various molecules at high concentrations and a powerful signaling molecule at subtoxic concentrations [31–33]. HNE activates various signaling pathways including MAP kinase pathways [34–40] and is involved in cellular functions such as proliferation [41–44], differentiation [45–48], and apoptosis [49–52]. A variety of genes can be regulated by HNE, especially genes involved in stress adaptation and detoxification, such as glutamate cysteine ligase [53–56] and aldose reductase [57]. In the present study, we investigated the regulatory effect of HNE on GGT expression and the possible signaling pathways involved in rat lung epithelial type II cells (L2 cell). GGT gene structure is complex. In the rat, GGT is a single copy gene whose expression is controlled by five tandem-arranged promoters from which seven transcripts are generated through alternative splicing [58]. These transcripts share a common coding sequence but have different 5′ untranslated regions. The mechanism regulating the expression of different types of GGT mRNA is not clear. In this study, we also examined the response of these different types of GGT mRNA to HNE.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). HNE was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Glycylglycine was from ICN Biochemical (Aurora, OH, USA). L-γ-Glutamyl 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (γ-Glu AMC) was purchased from Bachem Bioscience (King of Prussia, PA, USA). PD 98059, SB 203580, and JNK inhibitor I were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Antibodies for Western blotting were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). TRIzol reagent was from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). DNA-free was from Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). TaqMan reverse transcription reagent and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). All chemicals used were at least analytical grade.

Cell culture and treatments

L2 cells (from the American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in F-12K medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

HNE was dissolved in ethanol. PD98059 and SB203580 were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and JNK inhibitor I (JNKi) was dissolved in PBS. The final concentration of ethanol and DMSO in the medium was 0.05 and 0.1%, respectively. L2 cells were treated at about 90% confluence with different compounds as indicated under Results. Cells were rinsed with cold PBS before being harvested using rubber policemen.

GGT activity assay

GGT activity was measured according to the method described by Forman et al. [59], with slight modifications for use on a fluorescence microplate reader. Specificity of GGT activity was confirmed by acivicin, a specific GGT inhibitor. One unit of GGT activity was expressed as 1 pmol AMC produced per milligram protein per minute.

GGT mRNA assay

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and treated with DNA-free reagent according to the manufacturers’ protocols. DNA-free RNA samples were reverse transcribed using the TaqMan reverse transcription system (Applied Biosystems) and real-time PCRs were run with a Cepheid 1.2 real-time PCR machine. Briefly, 5 μl of reverse transcription reaction product was added to reaction tubes containing 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and primer pair specific for total or types of GGT mRNA; the total PCR sample was 25 μl. GAPDH was used as internal control (25 μl PCR: 2.5 μl RT reaction, 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, primers, and water). Table 1 shows the specific primer pairs for GAPDH and total and type-specific GGT mRNA. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

Primer pairs for GGT mRNA real-time PCR assay

| GGT mRNA type | Primers |

|---|---|

| All GGTs | Forward 5′-ACCACTCACCCAACCGCCTAC-3′ Reverse 5′-ATCCGAACCTTGCCGTCCTT-3′ |

| I | Forward 5′-GCTCATCACATCAGGCACCC-3′ Reverse 5′-AAACCCACAGCCAATCTTCC-3′ |

| II | Forward 5′-CCACCAGTGTTGACCATCCTC-3′ Reverse 5′-AAACCCACAGCCAATCTTCC-3′ |

| III | Forward 5′-ATCCCAAGCCCTCCTCACC-3′ Reverse 5′-AAACCCACAGCCAATCTTCC-3′ |

| IV | Forward 5′-GCTTGTTGACCTTGGGCATCTG-3′ Reverse 5′-AAACCCACAGCCAATCTTCC-3′ |

| V | Forward 5′-GCTTGTTGACCTTGGGCATCTG-3′ Reverse 5′-AAACCCACAGCCAATCTTCC-3′ |

| GAPDH | Forward 5′-ACCCCCAATGTATCCGTTGT-3′ Reverse 5′-TACTCCTTGGAGGCCATGT-3′ |

Primer pairs for types IV and V each generate two products, due to alternative splicing. Only mRNA types I, II, and V-2 were detectable in L2 cells. PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing after gel purification.

Western blotting assay

Briefly, protein was extracted with M-PER extraction buffer (Pierce) and 35 μg of total protein was heated for 15 min at 95°C in a 2× loading buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (Tris base, pH 6.5, glycerol, DTT, and pyronin Y), electrophoresed under denaturing conditions on a 10% Tris–glycine acrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with appropriate primary antibody in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). After being washed with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TTBS), the membrane was incubated with appropriate secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. After TTBS washing, the membrane was treated with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) reagent mixture for 5 min. Film exposure was done with Hyperfilm ECL film (Amersham).

Statistical analysis

We used the comparative ΔΔCT method for the relative mRNA quantitation. The relative quantification of target, normalized to an internal control (GAPDH), and an untreated sample is given by relative quantitation = 2−ΔΔCT, ΔΔCT being defined as the difference of mean ΔCT(HNE treated sample) and mean ΔCT(untreated sample) and ΔCT as the difference in mean CT(GGT) and CT(GAPDH) as the internal control. Threshold cycles (CT) were selected in the line in which all samples were in logarithmic phase.

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error. Sigma Stat software was used for statistical analysis and statistical significance was accepted when p < 0.05. The Student t test was used to analyze GGT activity data, and the Tukey test was used for comparison of mRNA level.

Results

HNE exposure increased both GGT activity and total GGT mRNA content in L2 cells

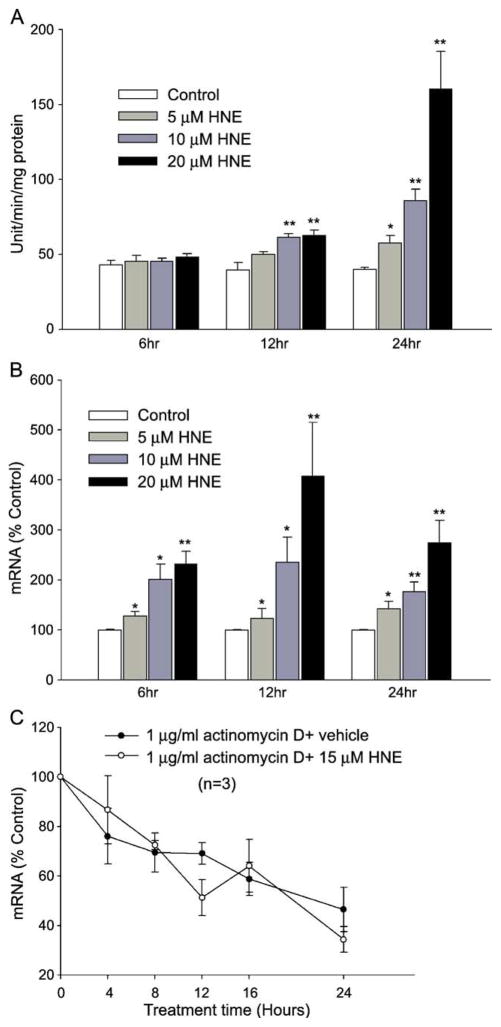

HNE is present in the free form at 0.3–0.7 μM in human plasma in controls and can increase 10 times or more during oxidative stress in vivo [60–63]. The HNE concentrations used in this study (5–20 μM) did not inhibit cell growth or cause any morphological changes. Exposure of L2 cells to 5–20 μM HNE increased GGT activity significantly (Fig. 1A). No significant increase in GGT activity was observed at 6 h after HNE treatment. However, 10 and 20 μM HNE significantly increased GGT activity by 12 h and all three concentrations used increased GGT activity by 24 h.

Fig. 1.

GGT activity and mRNA in HNE-treated L2 cells. (A) HNE increased GGT activity in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Data are means ± SEM; n = 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (B) GGT mRNA content was increased by HNE in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Cells were treated and GGT mRNA was determined using the real-time PCR assay. The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by DNA sequencing. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, n = 5. (C) GGT mRNA decay curve. Cells were pretreated with 1 μg/ml actinomycin D for 4 h before being treated with/without HNE, and the total GGT mRNA was determined at different time points. n = 3.

The change in GGT mRNA content was measured using real-time PCR. GGT mRNA was increased significantly after a 6-h treatment at all HNE concentrations used. Maximal induction of GGT mRNA was reached 12 h after HNE treatment. By 24 h, the mRNA content decreased compared to that at 12 h but was still significantly higher than control (Fig. 1B). Thus, exposure to HNE increased both GGT activity and total mRNA content in time- and dose- dependent manners in L2 cells.

HNE increased GGT mRNA at the transcription level

To elucidate whether HNE increased GGT mRNA at the transcriptional or the mRNA stability level, L2 cells were preincubated with actinomycin D, an RNA transcription inhibitor, for 1 h and then treated with HNE. In the presence of actinomycin D, HNE caused neither an increase in GGT mRNA nor a change in the rate of GGT mRNA degradation, suggesting transcriptional regulation of GGT mRNA by HNE (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that HNE increases GGT mRNA by stimulating gene transcription rather than by increasing mRNA stability.

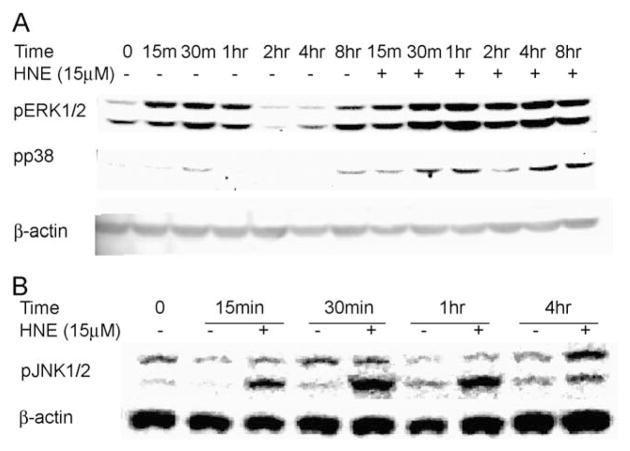

HNE activated ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK kinase pathways in L2 cells

HNE has been shown to initiate signaling cascades within the cell, resulting in gene expression, and this has often been identified as being dependent on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Using immunoblotting to the phosphorylated forms of these kinases, we demonstrated that HNE activated all three major MAP kinases in L2 cells (Fig. 2). Phosphorylated ERK was significantly increased after 2 h of HNE treatment and remained activated for at least 8 h (Fig. 2A). Phosphorylation of p38MAPK became significant 30 min after HNE treatment. Activation of JNK was observed as early as 15 min and remained active for several hours after HNE exposure. These data indicate that HNE provokes a complex of signaling pathways, each with unique kinetics.

Fig. 2.

HNE activated the major three MAP kinase pathways in L2 cells. (A) Phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and phospho-p38 kinase (pp38) and (B) phospho-JNK1/2 (pJNK1/2). Actin was used as a loading control.

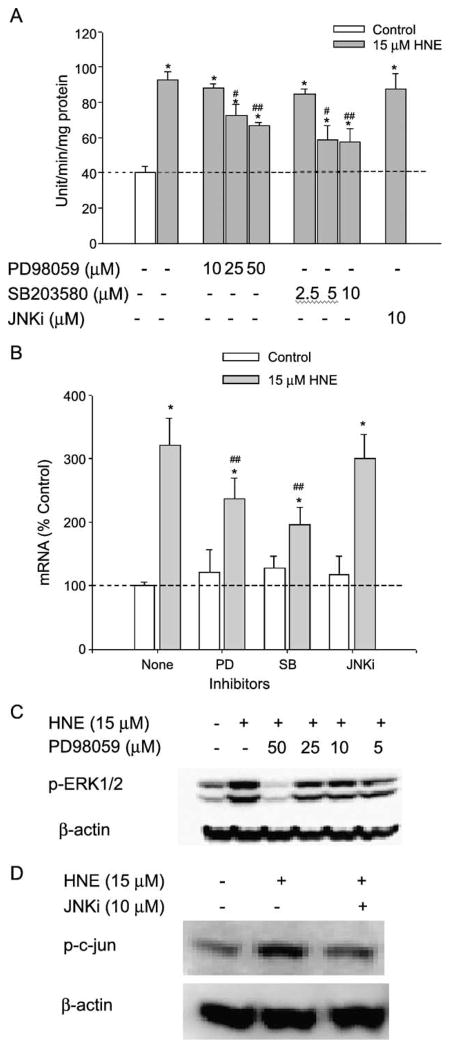

Both PD98059 and SB203580 attenuated the HNE-mediated increase in GGT activity and GGT mRNA

To investigate whether any the three major MAPK pathways were involved in the HNE-mediated induction of GGT in L2 cells, chemical inhibitors with relatively high specificity for each of the three major MAPK pathways were used over a range of concentrations. As shown in Fig. 3A, pretreatment of L2 cells for 1 h with increasing concentrations of PD98059, the ERK pathway inhibitor, significantly attenuated HNE-mediated induction in GGT activity. Over the same concentration range, PD98059 also produced increasing inhibition of the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 3C). Nonetheless, complete inhibition of the ERK pathway resulted in only partial inhibition of HNE induction of GGT (maximum inhibition was 49.1 ± 4.9%). At concentrations as low as 5 μM, the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 also significantly reduced the increase in GGT activity by HNE. As doubling the concentration of SB203580 produced no greater effect on HNE induction of GGT, it seems that p38MAPK also is only partially responsible for GGT induction by HNE (maximum inhibition was 66.8 ± 6.0%). In contrast, JNKi had no effect on GGT activity induction by HNE at a concentration that completely inhibited the phosphorylation of c-Jun by JNK1/2 (Fig. 3D). The effects of the major three MAPK inhibitors on GGT mRNA induction by HNE are consistent with their effects on GGT activity induction (Fig. 3B). Therefore, our results suggest that at least one of the two p38MAPK isoforms, α and β, that SB203580 inhibits, and at least one of the ERK isoforms, ERK1 and ERK2, that PD 98059 inhibits, were partially responsible for HNE-mediated GGT induction. On the other hand, the data indicate that although JNK1/2 was activated by HNE, it is not involved in GGT induction by HNE in L2 cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of MAP kinase inhibitors on HNE-mediated induction of GGT expression. L2 cells were pretreated with MAPK inhibitors as shown for 1 h before HNE treatment: 24 h for activity assay, 12 h for mRNA assay, and 1 h for Western blots. (A) Effects of MAP kinase inhibitors on GGT activity. (B) Effects of MAP kinase inhibitors on total GGT mRNA. Final concentration of MAP kinase inhibitors in the medium: PD98059, 50 μM; SB203580, 5 μM; and JNKi, 10 μM. (C) Effects of different concentrations of PD98059 on phosphorylation of ERK1/2. (D) JNKi-blocked phosphorylation of c-Jun increased by HNE. *p < 0.01 in comparison with vehicle control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 in comparison with HNE treatment, n = 3.

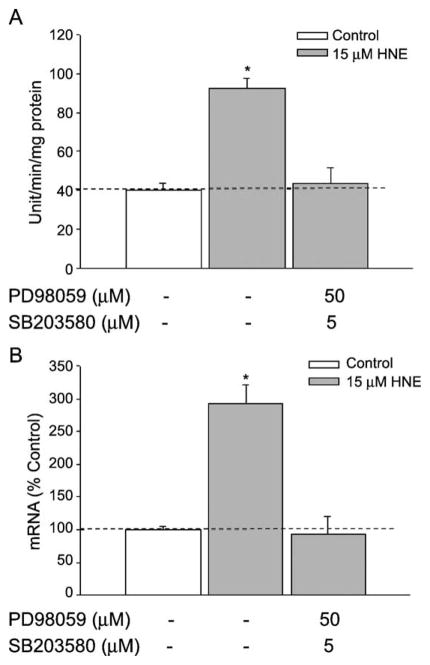

As the maximum percentage inhibition of the elevation in GGT expression by either PD98059 or SB203580 alone was incomplete, we determined whether inhibiting ERK and p38MAPK simultaneously would produce complete inhibition. L2 cells were pretreated with PD98059 (50 μM) and SB203580 (5 μM) together before cells were exposed to HNE. We found that the presence of both inhibitors blocked the HNE-induced GGT expression (both activity and mRNA, Fig. 4) completely, indicating that the two inhibitors act on separate pathways rather than on different steps along one pathway.

Fig. 4.

Combined effects of PD98059 and SB203580 on GGT induction. L2 cells were pretreated with the cocktail of PD98059 (50 μM) and SB203580 (5 μM) for 1 h before HNE treatment. 24 or 12 h after HNE exposure, cells were collected for activity or mRNA assay, respectively. (A) Effects on GGT activity. (B) Effects on GGT mRNA. *p < 0.01, comparison with vehicle control, n = 3.

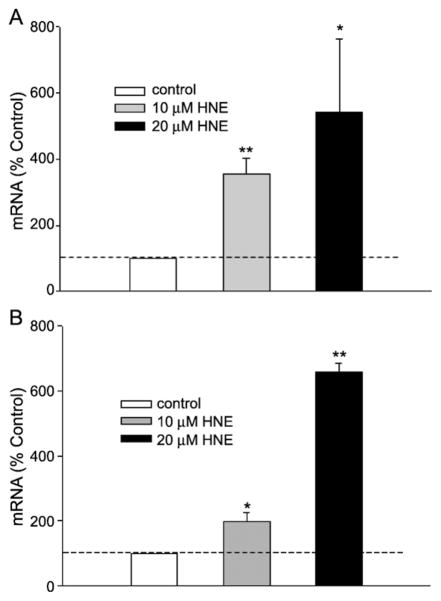

HNE exposure increased GGT mRNA types I and V-2 expression in L2 cells

Rat GGT is a single-copy gene from which seven transcripts are produced that share the same coding sequence but differ in their 5′ untranslated regions. To investigate which type of GGT mRNAs are induced by HNE we used specific primers for each rat GGT transcript and real-time PCR to measure the expression pattern of specific GGT mRNA types after HNE exposure. We found that L2 cells, which are derived from Lewis rat alveolar epithelial type II cells, constitutively express mRNA types I, II, and V-2. HNE exposure increased types I and V-2, but not type II (Fig. 5). The data suggest that the expression of different types of GGT mRNA is regulated by different mechanisms. Thus, HNE induces specific GGT mRNA types in L2 cells, demonstrating differential regulation through the various promoters.

Fig. 5.

HNE increased types (A) I and (B) V-2 GGT mRNA. Specific primer pairs against the 5′ untranslated region of each type of GGT mRNA were used in the real-time PCR assay, and the PCR products were confirmed with DNA sequencing. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 5.

Discussion

We and others have shown the increase in GGT expression in response to oxidants. Here our results showed that HNE, an end product of lipid peroxidation, increased GGT expression at the enzymatic activity and mRNA levels. GGT is a glycosylated protein and Western blots therefore show smears. GGT is not made as a proenzyme and therefore activity should correlate with protein. Indeed, using an antibody to a GGT peptide domain, we have previously demonstrated that GGT protein correlated with activity in both GGT induction in L2 cells by menadione [64] and transfection of human GGT into rat L2 cells [65].

Although the JNK, ERK, and p38MAPK pathways were all activated, only the ERK and p38MAPK pathways were involved in GGT induction by HNE. In addition, although L2 cells express types I, II, and V-2 GGT transcripts, only type I and type V-2 GGT mRNA were induced. This indicates the presence of HNE-responsive elements in the promoter regions for specific transcripts that will be pursued in the future.

It is well established that despite the toxicity of HNE, this strong electrophile is able to signal for the synthesis of enzymes such as aldose reductase [57], glutamate cysteine ligase (the rate-limiting enzyme for de novo GSH synthesis) [56,66], and glutathione S-transferase [67–69], which are involved in its detoxification as well as that of other endogenous and xenobiotic electrophiles. To this list of HNE-inducible enzymes, we now add GGT, which is involved in supplying cysteine for GSH synthesis. The increase in GSH synthesis in response to HNE exposure can maintain GSH level and allow cells to adapt to oxidative stress and toxicity of electrophiles.

Many extracellular stimuli elicit specific biological responses through the activation of MAPK cascades. Previously, Sinha et al. found that rat liver epithelial cells became GGT positive after transformation with Ras [70,71], which could activate ERK via the Ras–Raf–ERK pathway. All three MAPKs were activated by HNE in L2 cells. Nonetheless, very little is known about the possible involvement of the MAPK signaling pathways in increased expression of GGT, particularly by oxidative stress. Therefore to begin an investigation of the mechanism underlying increased expression of GGT by HNE in L2 cells, we investigated the involvement of the three major MAPK pathways (ERK, p38MAPK, and JNK) by using MAPK inhibitors. Considering that chemical inhibitors for a signaling pathway may have nonspecific effects on molecules other than their targets at higher concentration, we used inhibitors at concentrations that are specific [72–74]. PD98059 and SB203580, specific inhibitors for the ERK and p38MAPK signaling pathways, respectively, attenuated the HNE-mediated increase in GGT activity and mRNA content, but the maximal inhibitory effect of either alone was not complete. In combination, however, PD98059 and SB203580 blocked HNE-induced GGT expression completely, suggesting that the ERK1/2 and p38MAPK signaling pathways were separate in their effects upon the HNE-mediated increase in GGT expression. Interestingly the maximal inhibition by the inhibitors added to nearly 100%. For the increase in GGT activity by HNE, maximal PD98059 inhibition was 49.1 ± 4.9%, whereas SB203580 maximally inhibited 66.8 ± 6.0%. For the increase in GGT mRNA by HNE, PD98059 inhibited 38.7 ± 3.2%, whereas SB203580 inhibited 57.2 ± 4.0%. These results suggest that the ERK and p38MAPK pathways acted independently to produce part of the increase in HNE-induced expression of GGT but together accounted for the whole induction.

Our experience with several lung epithelial cell lines has shown that transient transfection rates are too low (<10%) for successful dominant negative protein expression using a variety of commercial liposomal delivery systems. Therefore, for PD98059, which had its maximal effect at the relatively high concentration of 50 μM, and JNKi, which did not inhibit, it was important to show that they actually inhibited their targets at the concentrations used. This was demonstrated here for PD98059 by the proportional increase in the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation and GGT expression. Indeed, such concentration dependence of the small-molecular-weight inhibitors has an advantage over the use of dominant negative proteins that must be expressed at high enough concentrations to outcompete their endogenous counterpart, running the risk of nonspecific protein–protein interactions.

JNK, also called stress-activated protein kinase, can be activated by various stimuli, such as irradiation, heat shock, hyperosmotic shock, inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress [75]. JNK activation can positively regulate the expression of genes involved in cellular response to stresses. As GGT is a necessary component of cellular adaptation to oxidative stress and HNE activated JNK in L2 cells, we hypothesized that JNK could play a positive role in HNE-induced expression of GGT. However, the JNK inhibitor has no effect on HNE-mediated induction of GGT activity although it inhibited c-Jun phosphorylation at the concentration used. These data suggest that the JNK1/2 pathway is not involved in GGT induction by HNE.

In the rat, GGT is a single-copy gene whose expression is regulated by five tandemly arranged promoters; alternative splicing from two of these generates seven transcripts. The expression of these seven GGT mRNAs varies with tissue and development phase [58]. It was found that in Sprague–Dawley rats, fetal rat lung mainly expressed types I and II GGT mRNAs, which were replaced by type III after birth [76]. Our results showed, however, that types I, II, and V-2 of GGT mRNA were the major types of GGT mRNA expressed in L2 cells, a cell line derived from lung epithelial type II cells of the Lewis rat. We did not find expression of type III GGT mRNA in L2 cells. Whether this indicates a difference in cell type distribution or rat strains is unclear but as the lung is composed of 40 cell types, a difference between whole tissue and one derived cell line is not surprising.

Increased GGT expression in response to oxidative stress was first shown in rat L2 cells in this laboratory [29]. Subsequently, others have shown that GGT expression in the lung can be increased during oxidative stress caused by various agents, including the quinones (menadione, DMNQ, and TBHQ), NO2, and hyperoxia [25,26,30,77]. Takahashi et al. [25] then showed that oxidative stress specifically induced type I GGT mRNA in Sprague–Dawley rat lungs. Here, we report that the expression of both types I and V-2 but not type II GGT mRNA was increased after HNE exposure. Previously, type V mRNA (both V-1 and V-2) was found to be expressed in undifferentiated rat H5 hepatoma cells [78], and types II, III, and IV were shown to be inducible by aflatoxin B1, hyperoxia, and xanthine/xanthine oxidase in a tissue-specific manner [24,76,79]. Thus, GGT expression is redox-regulated, although each promoter is regulated by both tissue-specific factors and redox-sensitive factors. Although the physiological significance of having multiple transcripts coding for the same protein remains unclear, perhaps the multiple promoters provide a fail-safe redundancy mechanism allowing cells an increased probability of increasing GGT in response to a variety of stimuli. Yet, little is known about the regulation of any of these mRNA types beyond the observation that oxidants and electrophiles can cause an increase in the various transcripts.

The lung is frequently exposed to ROS/RNS from air pollutants (NO2, ozone, particulates, or smoke) or released by neutrophils recruited in lung inflammation (i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis). In response to oxidative stress, cells increase the expression of genes involved in antioxidant and detoxification systems as an adaptive response. GGT, which breaks down circulating glutathione and provides cells with cysteine for de novo GSH synthesis, plays an essential role in defense against oxidants and electrophiles, including xenobiotics in the lung, as demonstrated in GGT knockout mice [4,5,16]. In the present study, we provided evidence that 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, an end product of lipid peroxidation during oxidative stress, increased both GGT activity and mRNA content in L2 cells. We also showed that HNE increased GGT expression via activation of ERK and p38MAPK signaling pathways.

References

- 1.Tate SS, Meister A. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase: catalytic, structural and functional aspects. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;39:357–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00232585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meister A. On the enzymology of amino acid transport. Science. 1973;180:33–39. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4081.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanigan MH, Ricketts WA. Extracellular glutathione is a source of cysteine for cells that express gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6302–6306. doi: 10.1021/bi00075a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman MW, Wiseman AL, Shi ZZ, Carter BZ, Barrios R, Ou CN, Chevez-Barrios P, Wang Y, Habib GM, Goodman JC, Huang SL, Lebovitz RM, Matzuk MM. Growth retardation and cysteine deficiency in gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7923–7926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jean JC, Liu Y, Brown LA, Marc RE, Klings E, Joyce-Brady M. Gamma-glutamyl transferase deficiency results in lung oxidant stress in normoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L766–776. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00250.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolicchi A, Sotiropuolou M, Perego P, Daubeuf S, Visvikis A, Lorenzini E, Franzini M, Romiti N, Chieli E, Leone R, Apostoli P, Colangelo D, Zunino F, Pompella A. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase catalyses the extracellular detoxification of cisplatin in a human cell line derived from the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakoby WB. Enzymatic Basis of Detoxification. New York: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soleo L, Strzelczyk R. [Xenobiotics and glutathione] G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 1999;21:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tate SS, Meister A. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase from kidney. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:400–419. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakes SM, Takahashi Y, Williams MC, Joyce-Brady M. Ontogeny of gamma-glutamyltransferase in the rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L739–744. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.4.L739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce-Brady M, Takahashi Y, Oakes SM, Rishi AK, Levine RA, Kinlough CL, Hughey RP. Synthesis and release of amphipathic gamma-glutamyl transferase by the pulmonary alveolar type 2 cell: its redistribution throughout the gas exchange portion of the lung indicates a new role for surfactant. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14219–14226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantin AM, North SL, Hubbard RC, Crystal RG. Normal alveolar epithelial lining fluid contains high levels of glutathione. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:152–157. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland MW, Glass M, Nelson J, Lyen Y, Forman HJ. Oxygen toxicity: loss of lung macrophage function without metabolite depletion. Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rojas E, Valverde M, Kala SV, Kala G, Lieberman MW. Accumulation of DNA damage in the organs of mice deficient in gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase. Mutat Res. 2000;447:305–316. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jean JC, Harding CO, Oakes SM, Yu Q, Held PK, Joyce-Brady M. γ-Glutamyl transferase (GGT) deficiency in the GGTenu1 mouse results from a single point mutation that leads to a stop codon in the first coding exon of GGT mRNA. Mutagenesis. 1999;14:31–36. doi: 10.1093/mutage/14.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrios R, Shi ZZ, Kala SV, Wiseman AL, Welty SE, Kala G, Bahler AA, Ou CN, Lieberman MW. Oxygen-induced pulmonary injury in gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-deficient mice. Lung. 2001;179:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s004080000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodanszky H, Greengard O, Den T. Pulmonary and hepatic activities of membrane-bound enzymes in man and rat. Enzyme. 1980;25:97–101. doi: 10.1159/000459226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanigan MH. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase, a glutathionase: its expression and function in carcinogenesis. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;111–112:333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitfield JB. Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38:263–355. doi: 10.1080/20014091084227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bots ML, Salonen JT, Elwood PC, Nikitin Y, Freire de Concalves A, Inzitari D, Sivenius J, Trichopoulou A, Tuomilehto J, Koudstaal PJ, Grobbee DE. Gamma-glutamyltransferase and risk of stroke: the EUROSTROKE project. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(Suppl 1):i25–29. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.suppl_1.i25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emdin M, Passino C, Donato L, Paolicchi A, Pompella A. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase as a risk factor of ischemic stroke might be independent of alcohol consumption. Stroke. 2002;33:1163–1164. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000012344.35312.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitfield JB, Zhu G, Nestler JE, Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic covariation between serum gamma-glutamyl-transferase activity and cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1426–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wannamethee G, Ebrahim S, Shaper AG. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase: determinants and association with mortality from ischemic heart disease and all causes. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:699–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths SA, Good VM, Gordon LA, Hudson EA, Barrett MC, Munks RJ, Manson MM. Characterization of a promoter for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activated in rat liver in response to aflatoxin B1 and ethoxyquin. Mol Carcinog. 1995;14:251–262. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi Y, Oakes SM, Williams MC, Takahashi S, Miura T, Joyce-Brady M. Nitrogen dioxide exposure activates gamma-glutamyl transferase gene expression in rat lung. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;143:388–396. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu RM, Hu H, Robison TW, Forman HJ. Increased gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activities enhance resistance of rat lung epithelial L2 cells to quinone toxicity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:192–197. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.2.8630270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu RM, Hu H, Robison TW, Forman HJ. Differential enhancement of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase by tert-butylhydroquinone in rat lung epithelial L2 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:186–191. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.2.8630269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu RM, Shi MM, Giulivi C, Forman HJ. Quinones increase gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase expression by multiple mechanisms in rat lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L330–336. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.3.L330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kugelman A, Choy HA, Liu R, Shi MM, Gozal E, Forman HJ. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase is increased by oxidative stress in rat alveolar L2 epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:586–592. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.5.7946387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Klaveren RJ, Hoet PH, Pype JL, Demedts M, Nemery B. Increase in gamma-glutamyltransferase by glutathione depletion in rat type II pneumocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:525–534. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forman HJ, Dickinson DA, Iles KE. HNE—signaling pathways leading to its elimination. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakashima I, Liu W, Akhand AA, Takeda K, Kawamoto Y, Kato M, Suzuki H. 4-Hydroxynonenal triggers multistep signal transduction cascades for suppression of cellular functions. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poli G, Schaur RJ. 4-Hydroxynonenal in the pathomechanisms of oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:315–321. doi: 10.1080/713803726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakishita H, Hattori Y. Vascular smooth muscle cell activation and growth by 4-hydroxynonenal. Life Sci. 2001;69:689–697. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soh Y, Jeong KS, Lee IJ, Bae MA, Kim YC, Song BJ. Selective activation of the c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase pathway during 4-hydroxynonenal-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:535–541. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camandola S, Poli G, Mattson MP. The lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2,3-nonenal increases AP-1-binding activity through caspase activation in neurons. J Neurochem. 2000;74:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamagno E, Robino G, Obbili A, Bardini P, Aragno M, Parola M, Danni O. H2O2 and 4-hydroxynonenal mediate amyloid beta-induced neuronal apoptosis by activating JNKs and p38MAPK. Exp Neurol. 2003;180:144–155. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruckner SR, Estus S. JNK3 contributes to c-jun induction and apoptosis in 4-hydroxynonenal-treated sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:665–670. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song BJ, Soh Y, Bae M, Pie J, Wan J, Jeong K. Apoptosis of PC12 cells by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is mediated through selective activation of the c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;130–132:943–954. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumagai T, Nakamura Y, Osawa T, Uchida K. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:240–245. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dianzani MU, Barrera G, Parola M. 4-Hydroxy-2,3-nonenal as a signal for cell function and differentiation. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46:61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semlitsch T, Tillian HM, Zarkovic N, Borovic S, Purtscher M, Hohenwarter O, Schaur RJ. Differential influence of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal on the growth of human lymphatic leukaemia cells and human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1689–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe T, Pakala R, Katagiri T, Benedict CR. Lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal acts synergistically with serotonin in inducing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Atherosclerosis. 2001;155:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00526-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cambiaggi C, Dominici S, Comporti M, Pompella A. Modulation of human T lymphocyte proliferation by 4-hydroxynonenal, the bioactive product of neutrophil-dependent lipid peroxidation. Life Sci. 1997;61:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarkovic N, Zarkovic K, Schaur RJ, Stolc S, Schlag G, Redl H, Waeg G, Borovic S, Loncaric I, Juric G, Hlavka V. 4-Hydroxynonenal as a second messenger of free radicals and growth modifying factor. Life Sci. 1999;65:1901–1904. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Sharma R, Sharma A, Awasthi S, Awasthi YC. Lipid peroxidation and cell cycle signaling: 4-hydroxynonenal, a key molecule in stress mediated signaling. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:319–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rinaldi M, Barrera G, Spinsanti P, Pizzimenti S, Ciafre SA, Parella P, Farace MG, Signori E, Dianzani MU, Fazio VM. Growth inhibition and differentiation induction in murine erythroleukemia cells by 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:629–637. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrera G, Di Mauro C, Muraca R, Ferrero D, Cavalli G, Fazio VM, Paradisi L, Dianzani MU. Induction of differentiation in human HL-60 cells by 4-hydroxynonenal, a product of lipid peroxidation. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197:148–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90416-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji C, Amarnath V, Pietenpol JA, Marnett LJ. 4-Hydroxynonenal induces apoptosis via caspase-3 activation and cytochrome c release. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:1090–1096. doi: 10.1021/tx000186f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herbst U, Toborek M, Kaiser S, Mattson MP, Hennig B. 4-Hydroxynonenal induces dysfunction and apoptosis of cultured endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:295–303. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199911)181:2<295::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruman I, Bruce-Keller AJ, Bredesen D, Waeg G, Mattson MP. Evidence that 4-hydroxynonenal mediates oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5089–5100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Awasthi YC, Sharma R, Cheng JZ, Yang Y, Sharma A, Singhal SS, Awasthi S. Role of 4-hydroxynonenal in stress-mediated apoptosis signaling. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu RM, Borok Z, Forman HJ. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal increases gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase gene expression in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:499–505. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.4.4307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu RM, Gao L, Choi J, Forman HJ. Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase: mRNA stabilization and independent subunit transcription by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L861–869. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.5.L861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dickinson DA, Forman HJ. Glutathione in defense and signaling: lessons from a small thiol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;973:488–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickinson DA, Iles K, Watanabe N, Iwamoto T, Zhang H, Krzywanski DM, Forman HJ. 4-Hydroxynonenal induces glutamate cysteine ligase through JNK in HBE1 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:974. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spycher S, Tabataba-Vakili S, O’Donnell VB, Palomba L, Azzi A. 4-Hydroxy-2,3-trans-nonenal induces transcription and expression of aldose reductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:512–516. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chikhi N, Holic N, Guellaen G, Laperche Y. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase gene organization and expression: a comparative analysis in rat, mouse, pig and human species. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;122:367–380. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(99)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Forman HJ, Shi MM, Iwamoto T, Liu RM, Robison TW. Measurement of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase activities in cells. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:66–71. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Esterbauer H, Zollner H, Schaur RJ. Aldehydes formed by lipid peroxidation: mechanisms of formation, occurrence and determination. Vol. 1. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1990. pp. 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selley ML, Bartlett MR, McGuiness JA, Hapel AJ, Ardlie NG. Determination of the lipid peroxidation product trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal in biological samples by high-performance liquid chromatography and combined capillary column gas chromatography–negative-ion chemical ionisation mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 1989;488:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grune T, Siems WG, Kowalewski J, Esterbauer H. Postischemic accumulation of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in rat small intestine. Life Sci. 1994;55:694–698. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strohmaier H, Hinghofer-Szalkay H, Schaur RJ. Detection of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) as a physiological component in human plasma. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signaling. 1995;11:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(94)00027-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kugelman A, Choy HA, Liu R, Shi MM, Gozal E, Forman HJ. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase is increased by oxidative stress in rat alveolar L2 epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:586–592. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.5.7946387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi M, Gozal E, Choy HA, Forman HJ. Extracellular glutathione and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase prevent H2O2-induced injury by 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;15:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90125-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dickinson DA, Forman HJ. Cellular glutathione and thiols metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fukuda A, Nakamura Y, Ohigashi H, Osawa T, Uchida K. Cellular response to the redox active lipid peroxidation products: induction of glutathione S-transferase P by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:505–509. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singhal SS, Godley BF, Chandra A, Pandya U, Jin GF, Saini MK, Awasthi S, Awasthi YC. Induction of glutathione S-transferase hGST 5.8 is an early response to oxidative stress in RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1999;40:2652–2659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raza H, Robin MA, Fang JK, Avadhani NG. Multiple isoforms of mitochondrial glutathione S-transferases and their differential induction under oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2002;366:45–55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sinha S, Marshall CJ, Neal GE. γ-Glutamyltranspeptidase and the ras-induced transformation of a rat liver cell line. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1440–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sinha S, Hockin LJ, Neal GE. Transformation of a rat liver cell line: neoplastic phenotype and regulation of gamma glutamyl transpeptidase in tumour tissue. Cancer Lett. 1987;35:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(87)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, Meier R, Cohen P, Gallagher TF, Young PR, Lee JC. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paul A, Wilson S, Belham CM, Robinson CJ, Scott PH, Gould GW, Plevin R. Stress-activated protein kinases: activation, regulation and function. Cell Signalling. 1997;9:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joyce-Brady M, Oakes SM, Wuthrich D, Laperche Y. Three alternative promoters of the rat gamma-glutamyl transferase gene are active in developing lung and are differentially regulated by oxygen after birth. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1774–1779. doi: 10.1172/JCI118605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knickelbein RG, Ingbar DH, Seres T, Snow K, Johnston RB, Jr, Fayemi O, Gumkowski F, Jamieson JD, Warshaw JB. Hyperoxia enhances expression of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and increases protein S-glutathiolation in rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L115–122. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.1.L115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nomura S, Lahuna O, Suzuki T, Brouillet A, Chobert MN, Laperche Y. A specific distal promoter controls gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase gene expression in undifferentiated rat transformed liver cells. Biochem J. 1997;326:311–320. doi: 10.1042/bj3260311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Markey CM, Rudolph DB, Labus JC, Hinton BT. Oxidative stress differentially regulates the expression of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase mRNAs in the initial segment of the rat epididymis. J Androl. 1998;19:92–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]