Umbilical cord blood as personal health insurance for your child. Long before it arrives, your baby is always in your thoughts. You will do anything to ensure your child’s health and happiness. The birth offers you a unique opportunity. By storing healthy young stem cells from the umbilical cord blood, you guarantee that for the rest of its life your child will have rapid access to his or her own, perfectly matching stem cells, and hence the chance of a new start in health should a serious illness ever arise. That is why, for more and more parents, cord stem cell storage is now a part of modern health care provision. Fortunately, there are experts in the field of cord blood storage who can help you achieve your desire” (1).

This text, or others like it, is designed to persuade parents to put their child’s cord blood into storage at commercial blood banks. This kind of service comes at a one-off cost of around 2000 euros to 2500 euros plus an annual fee. Naturally, many parents and grandparents are now asking themselves whether, instead of a savings account, they should not endow the new arrival with his or her “own stem cells,” and whether this investment in the child’s health is not worth 2000 euros.

Probing the facts behind the advertising promises

Many medical colleagues will have exactly the same thoughts when these parents come to them with questions. The more commendable, then, that Gesine Kögler and Verena Reimann, researchers at the José Carreras Stem Cell Bank in Düsseldorf, together with Ursula Creutzig, chief executive of the German Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Hämatologie und Onkologie), have taken the trouble as qualified experts to examine these promises objectively (2). To do this, they have not just investigated the role of autologous cord blood for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (it does not have one), but have also looked into the possibilities for its use in regnerative medicine.

It is precisely the impression (the authors cite it themselves in the article) that “cord blood is an indispensable panacea that will come into use in regenerative medicine in the near future” that is supposed to provide the rationale for storing autologous cord blood. Stem cells, the “complete all-rounders,” will—so it is believed—repair diabetes, liver and lung damage, and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Like other authors before them (3), Reimann et al. examine the available data and show how shaky are the foundations on which these expectations rest. Most importantly, they offer recommendations to physicians on how to educate and advise those who come to them for guidance. A significant factor, which may perhaps not be understood by all medical colleagues with such clarity, is the difference between autologous and allogenous banking, and the problems relating to the “combined model”, which the authors explain at length.

Reservations expressed

Like Reimann et al., other authors have expressed reservations about the possibilities and opportunities associated with autologous cord blood banking. “NHS maternity units should not encourage commercial banking of umbilical cord blood” runs the headline of an article in the British Medical Journal that is worth reading (4); below the headline the message continues: “Storing cord blood at birth as insurance against future disease may sound like a good idea to parents, but it has worrying implications for NHS services and little chance of benefit.”

A survey of pediatric transplantation physicians in North America has just been carried out (5), the results of which are very relevant here. Asked what their attitude was to the autologous cord blood issue—this professional group would, after all, be the main users of banked cells—“very few” respondents said that they would recommend prophylactic autologous cryobanking to parents-to-be.

We seem, then, still to be left with the conclusion that Reimann et al. share with others: that the likelihood that autologous cord blood will be needed is extremely small, and the hope that it can be used to cure diabetes or other diseases is no more than speculative (4).

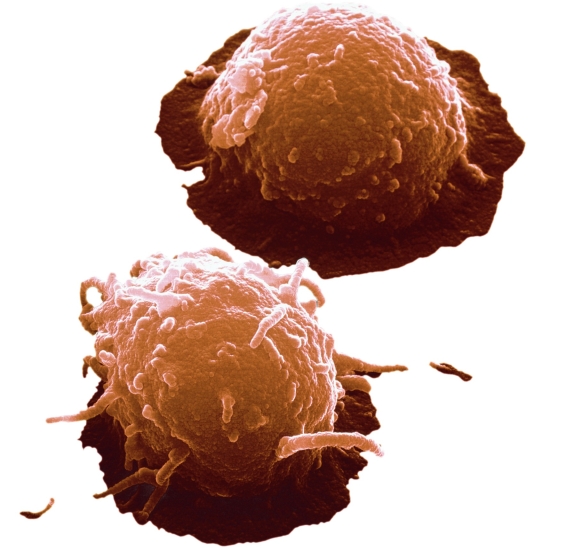

Figure.

Stem Cells from Umbilical Cord.

Jürgen Berger/SPL/Agentur Focus

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author has received support from the German José Carreras Leukemia Foundation for a third-party-funded project.

Editorial to accompany the article “Stem Cells Derived From Cord Blood in Transplantation and Regenerative Medicine” by Reimann et al. in this issue of Deutsches Ärzteblatt International

References

- 1. www.vita34.de. accessed on 9. 11. 2009.

- 2.Reimann V, Creuztig U, Kögler G. Stem cells derived from cord blood in transplantation and regenerative medicine [Stammzellen aus Nabelschnurblut in der Transplantations- und regenerativen Medizin] Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106(50):831–836. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinbrook R. The cord-blood bank controversies. NEJM. 2004;351:2255–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edozien LC. NHS maternity units should not encourage commercial banking of umbilical cord blood. BMJ. 2006;333:801–804. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38950.628519.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornley I, Eapen M, Sund L, Lee SJ, Davies SM, Joffe S. Private cord blood banking: experiences and views of pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation physicians. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1011–1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]