Abstract

Purpose

Drusen, which can be defined clinically as yellowish white spots in the outer retina, are cardinal features of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice have been reported to develop drusen and phenotypic features similar to AMD including an increased susceptibility to choroidal neovascularisation (CNV). Here we investigate the nature of the drusen-like lesions in vivo and further evaluate the Ccl2-/- mouse as a model for AMD.

Methods

We examined eyes of 2-25 month old Ccl2-/- and C57Bl/6 mice in vivo by autofluorescence scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AF-SLO), electroretinography, and measured the extent of laser- induced CNV by fluorescein fundus angiography. We also assessed retinal morphology using immunohistochemistry and quantitative histological and ultrastructural morphometry.

Results

The drusen-like lesions of Ccl2-/- mice comprise accelerated accumulation of swollen CD68+, F4/80+ macrophages in the subretinal space that are apparent as autofluorescent foci on AF-SLO. These macrophages contain pigment granules and phagosomes with outer segment and lipofuscin inclusions that might account for their autofluorescence. We only observed age-related RPE damage, photoreceptor loss and sub-RPE deposits but, despite the accelerated accumulation of macrophages, we identified no spontaneous CNV development in senescent mice and found a reduced susceptibility to laser-induced CNV in Ccl2-/- mice.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the lack of Ccl2 leads to a monocyte/macrophage trafficking defect during aging and to an impaired recruitment of these cells to sites of laser injury. Other, previously described features of Ccl2-/- mice that are similar to AMD may be the result of aging alone.

Keywords: Aging, MCP-1/Ccl2 knockout mouse, subretinal macrophages, Laser-induced CNV, autofluorescent SLO imaging, age-related macular degeneration, AMD, HRA2

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the commonest cause of vision loss in the elderly population in industrialized countries.1 A clinical hallmark of AMD is the appearance of drusen, which are opaque, yellowish white spots visible in the fundus.2 Histologically, drusen are extracellular deposits between the basal lamina of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and inner collagenous layer of Bruch’s membrane (BM). Drusen have a complex protein/lipid composition, that includes immunoglobulins, activated complement components and complement regulators 3, 4 as well as lipids, intracellular proteins and cytosolic stress response proteins.5

Targeted disruption of the gene encoding monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), also known as CC-cytokine ligand 2 (Ccl2), or its receptor CC-cytokine receptor 2 (Ccr2) in mice leads to defects in monocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation.6-8 Recently it has been reported that both Ccl2 and Ccr2 knockout mice develop drusen and other features of AMD, such as the accumulation of lipofuscin in RPE cells, progressive outer retinal degeneration and geographic/RPE atrophy. A higher incidence of spontaneous development of choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) was also reported in a proportion of senescent mice (4 out of 15 mice aged > 18 months).9

It has therefore been suggested, that chemokines and their receptors, including CCL2 and CCR2, might be involved in the etiology of AMD. While genetic data indicates that polymorphisms in the cytokine receptor CX3CR1 are associated with an increased risk of developing AMD,10, 11 an increased risk for AMD has not been associated with CCL2 or CCR2.12 Recently, it has also been shown that CX3CR1-positive microglia can be found ectopically in the outer retina and in the subretinal space of AMD patients in close proximity to drusen and to CNV. The CX3CR1 T280M-polymorphism leads to an impaired chemotactic response of monocytes to CCL2 in the presence of bound CX3CL1 in vitro.11 Furthermore with age, Cx3cr1 deficient mice show a progressive accumulation of microglia cells in the subretinal space. This leads to a drusen-like appearance in Cx3Cr1 knockout mice and is accompanied by retinal degeneration suggesting that CX3CR1 signalling in microglia might play a role in AMD development.11, 13

The absence to date of a genetic association between CCL2 or CCR2 and AMD therefore prompted us to characterise the drusen development in Ccl2 knockout mice in more detail and to re-evaluate them as a model for AMD.

Material and Methods

Animals

We used Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice on a C57Bl/6 background kept as a homozygous line (a kind gift from Dr. Kath Else at the University of Manchester from the original stock maintained by Barrett Rollins).14 Age-matched controls (C57Bl/6 6JOla Hsd, Harlan UK Limited, Blackthorn, UK) were kept in the same animal room and 12 hour light dark cycles. For in vivo procedures, mice were anesthetized by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a mixture of Domitor (medetomidine hydrochloride; 1 mg/ kg body weight), and ketamine (60 mg/kg body weight) in water. Whenever required the pupils were dilated using 1 drop of 1% tropicamide. The animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Autofluorescence scanning laser ophthalmosocopy (AF-SLO)

Autofluorescence imaging was performed using the HRA2 Scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Heidelberg engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) as previously described.15-17 Using a 55° angle lens, projection images of 30 frames per fundus were taken after positioning the optic disc in the center of the image and focussing on the outer retina. The number of autofluorescent spots per fundus image was determined for each eye and the mean number of autofluorescent spots per fundus image ± S.D. of the left and the right eye for each animal was calculated.

Histopathology

Paraffin embedded histology was performed as described before.18 Briefly, eyes were enucleated and fixed for at least 18 hours in Serras fixative and were embedded in paraffin after dehydration in 70% and 100 % isopropanol. Sections were cut at 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were obtained from the central and the peripheral region of sections containing the optic nerve. Rows of photoreceptors were counted in three columns per image from at least two images per animal and the mean number of photoreceptor rows ±S.D. per section was calculated for the central and the peripheral retina of each animal.

For ultrastructural analysis, eyes were enucleated and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.08M sodium cacodylate-HCl (pH 7.4) for at least 30 h at 4°C. The cornea and lens were removed and the eye cups orientated and post-fixed in 1% aqueous osmium tetroxide for 2 hours, dehydrated by passage through ascending ethanol series (50-100%) and propylene oxide and infiltrated overnight with 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide. After a further 8 hours in full resin, eyes were embedded in fresh resin and incubated overnight at 60°C. Semithin (0.7 μm) and ultrathin (70 nm) sections were cut in the inferior-superior axis passing through the optic nerve head using a Leica ultracut S microtome. Semithin sections were stained with a 1% mixture of toluidine blue-borax in 50% ethanol, and ultrathin sections sequentially contrasted with saturated ethanolic uranyl acetate and lead citrate for imaging in a JEOL 1010 TEM operating at 80kV. Images were captured using a Gatan Orius CCD camera calibrated against a 2160lines/mm grating (Agar Scientific, Stansted, UK) in Digital Micrograph format and exported as TIFFS into Image J for quantification. Bruch’s membrane (BM) thickness, defined from the basal lamina of the RPE cell to the basal lamina of the choroidal vessel, was measured in a uniform randomized way to prevent a potential bias by the observer’s choice. The average BM thickness in each eye was obtained from single images taken at a standard magnification of 5,000 positioned approximately 1 mm on each side of the optic nerve. After calibration of Image J, BM was rotated to the horizontal or vertical and a grid was superimposed on the image. Ten measurements were taken at points where grid lines passed across BM to yield an average value. Finally the average measurements for superior and inferior were added and a mean value ± standard deviation was obtained for BM thickness for each animal.

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were enucleated and the cornea and lens were removed during fixation in PBS/4% paraformaldehyde for one hour. Cryoprotection with PBS/20% sucrose over night at 4°C was performed before the eyes were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue Tek, Sakura Finetek, Thatcham, UK). 12 μm retinal sagittal sections were air dried for at least 1 h before rehydration of sections with PBS. For the CD68 immunohistochemistry, unspecific binding sites on the sections were blocked for one hour with PBS/1%BSA (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany)/5% non-specific goat serum (AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) including 0.3% Trition X-100 for permeabilisation before being incubated with a 1:200 dilution (0.5 μg/ml) of rat anti mouse CD68: Biotin antibody (#MCA1957B, clone FA-11, AbD serotec, Kidlington, UK) in blocking solution over night at 4°C. After 4-5 washes (5-10 min) in PBS at room temperature (RT) they were incubated with 1:500 Alexafluor 546 nm conjugated streptavdidin (#S11225, Invitrogen-Molecular probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 2 hours at RT, washed again 4-5 times in PBS and mounted with DAKO Fluorescent mounting medium containing Hoechst 33342 (DAKO, Cambridgeshire, UK). Since F4/80 staining was generally very weak, we used blocking and amplification reagents from the catalyzed signal amplification (CSA) system (#K1500, DAKO, Cambridgeshire, UK) according to manufacturers instruction together with the primary rat anti mouse F4/80:Biotin antibody (1:500 (0.2 μg/ml), #MCA497B, clone CI:A3-1, AbD serotec, Kidlington, UK) and the Alexafluor 546 nm conjugated streptavdidin (1:500, #S11225, Invitrogen-Molecular probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) as the final detecting antibody. Eyes for RPE/Choroidal flatmounts were fixed for 1 hour in PBS/4% paraformaldehyde, dissected and directly mounted on glas slides before images were taken using a Laser Scanning Microscope (LSM 510, Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Jena, Germany).

Electroretinography (ERG) and choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) analysis

Standard scotopic Ganzfield ERG’s were recorded from dark adapted mice (16h) from both eyes simultaneously (Espion E2, Diagnosys LLC, Cambridge, UK). All procedures for recording were performed under dim red light. Single flash recordings were obtained at increasing light intensities from 0.001 to 10 cds/m2. Ten responses per intensity level were averaged with an interstimulus interval of 30 sec (0.001-1cds/m2) and 60 sec (3, 5 and 10 cds/m2). A- and b- wave amplitudes were analysed using the Espion software (Diagnosys LLC, Cambridge, UK).

Laser induced CNV and quantification using fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was performed as described before.19 Three laser lesions per eye were delivered at 2- 3 disc diameters away from the papillae with an slit-lamp-mounted diode laser system (wavelength 680 nm; Keeler, UK; laser settings: 210 mW power, 100 ms duration, 100 μm spot diameter). After 2 weeks, in vivo FFA was performed and images from the early (90 s after fluorescein injection) and late (7 min) phase were obtained using a Kowa Genesis small animal fundus camera with appropriate filters. The pixel area of CNV-associated hyperfluorescence was quantified for each lesion using image analysis software (Image Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA) and the proportionate increase between early and late phase was calculated providing us with a measure for the degree of vascular permeability.

Results

Accelerated accumulation of autofluorescent foci in AF-SLO fundus images

Senescent Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice were evaluated by normal fundoscopy, which confirmed the drusen-like phenotype previously described.9 To characterize further the ocular phenotype during aging and learn more about potential pathological changes and the nature of the drusen like structures in vivo, we examined Ccl2-/- mice (n=11) and aged-matched C57Bl/6 wildtype mice (n=9) using autofluorescent scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AF-SLO) at different ages (2-3 month, 5-7 month, 16-18 month and 20-25 month). This confocal imaging technique enables us to detect changes in the normal distribution of fluorophores (e.g. lipofuscin) inside the retina and the RPE, which are often associated with pathological processes and provides some localization information, because it does not detect sub-RPE changes in pigmented animals, since the 488 nm laser light gets absorbed by the pigment.15

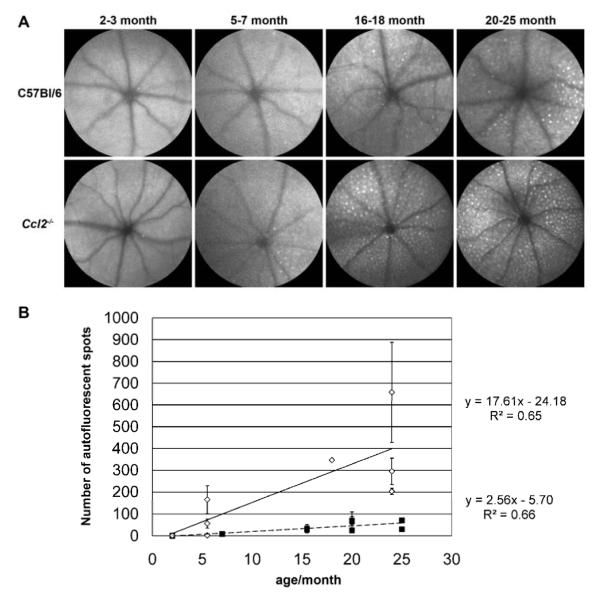

In wildtype C57Bl/6 mice we observed a consistent age-related increase in number of autofluorescent spots inside the retina up to 2 years (figure 1A, upper row). In Ccl2-/- mice the number of such autofluorescent spots also increased steadily with age but was consistently higher than in age-matched control (figure 1A, lower row). Quantitative analysis for each genotype confirmed a significant positive correlation of age and number of autofluorescent spots per fundus image for both genotypes (Pearson correlation C57Bl/6: r=0.813, p = 0.002, n= 11; Ccl2-/-: r = 0.806, p= 0.009, n= 9) and revealed a significantly higher number of autofluorescent spots in 16-25 month old Ccl2-/- mice compared with young Ccl2-/- (2-7 month), young C57Bl/6 (2-7 month) and old C57Bl/6 (16-25 month) mice (p<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test). This indicated that the accumulation of autofluorescent spots inside the retina is a normal age-related process that is accelerated in Ccl2-/- mice.

Figure 1. Accelerated accumulation of autofluorescent spots in Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice with age.

Autofluorescence scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AF-SLO) projection images of 30 frames taken with a 55°angle lens. (A) Representative fundus images obtained by AF-SLO imaging from both genotypes at 2-3 month, 5-7 month, 16-18 month and 20-25 month. While in both C57Bl/6 and Ccl2-/- mice the number of autofluorescent spots were increased with age, this process was accelerated and more pronounced in Ccl2-/- mice.

(B) Quantification of autofluorescent spots in C57Bl/6 (black squares, dashed line) and Ccl2-/- mice (open diamonds, continuous line) per AF-SLO images. The number of autofluorescent spots per AF-SLO image is shown as the mean number of spots ± S.D. of the right and the left eye for each animal. For both genotypes, the mean number of spots were significantly correlated with the age indicating an age-related increase of autofluorescent spots as a normal process (Pearson correlation C57Bl/6: r=0.813, p = 0.002, n= 11; Ccl2-/-: r = 0.806, p= 0.009, n= 9). One way ANOVA with bonferroni posthoc test revealed a significantly higher number of autofluorescent spots in 16-25 month old Ccl2-/- mice compared to aged-matched wildtype C57Bl/6 mice and compared to the young (2-7 month) groups of both genotypes (p<0.01).

Similar age-related loss of photoreceptors in wildtype C57Bl/6 and Ccl2 knockout mice

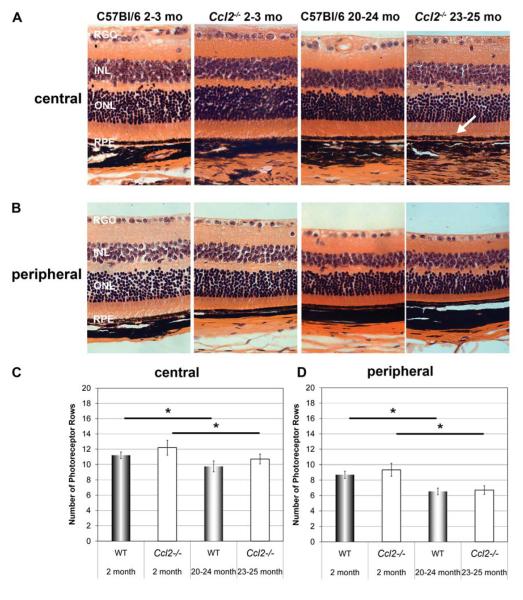

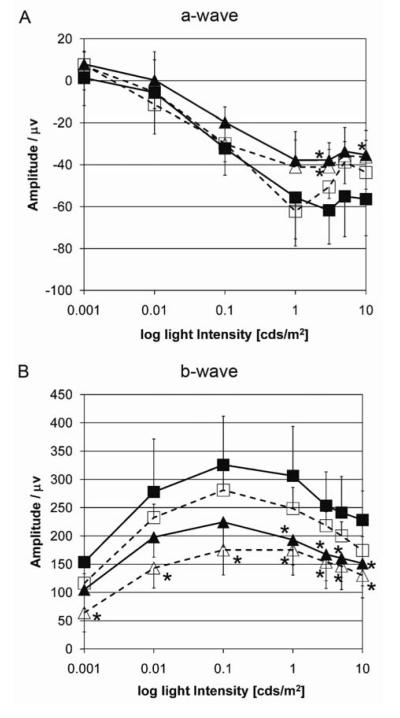

Histologically the retinas of Ccl2-/- mice and aged-matched wildtype controls appeared similar in both central and peripheral regions (figure 2), except for occasional large macrophage-like cells in the Ccl2-/- mice (see below). We observed a similar age-related loss of outer nuclear layer (ONL) cells in the central and peripheral retina of both genotypes (figure 2A, 2B), which was significantly different between young and old animals of both genotypes, but not between aged-matched wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice (figure 2C, 2D). Similarly we observed higher amplitude ERG recordings in young compared to 10-12 month old mice in both strains (figure 3A,3B, oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test, p<0.05), but no difference between aged-matched wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice (figure 3) indicating that the lack of Ccl2-/- does not enhance the normal age-related loss of retinal function.

Figure 2. Similar age-related photoreceptor loss in wildtype and Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice.

Comparison of central (A) and peripheral (B) retinal histology using hematoxylin eosin stained sagittal sections (5μm) of wildtype (C57Bl/6) and Ccl2-/- mice at respective ages. No obvious histological differences between age-matched wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice were found except the observation of some subretinal macrophage like cells in old Ccl2-/- mice (arrow). When comparing young versus old wildtype and young versus old Ccl2-/- mice, thinning of the ONL with age was obvious in both genotypes. RGC: retinal ganglion cell layer, INL: inner nuclear layer, ONL: outer nuclear layer, RPE: retinal pigment epithelium. Original magnification 400×. (C, D) Morphometric analysis of mean number of photoreceptor rows per section in the central (C) and the peripheral (D) retina for all animal groups (young Wt (n=5), young Ccl2-/- (n=5), old Wt (n=5), and old Ccl2-/- (n=6) mice). A significant reduction in rows of photoreceptors with age was found in the central and the peripheral retina in both genotypes, but no significant difference was found between aged-matched C57Bl/6 control and Ccl2-/- animals. (Kruskal Wallis Test (p=0.004) with subsequent pairwise comparison of all groups using the Man Whitney U test. Stars (*) indicate statistical significance based on the Man Whitney U test (p<0.05).

Figure 3. Similar age-related reduction of ERG amplitude in both genotypes.

Mean A-wave (A) and B- wave (B) amplitudes ± S.D. per group of animals (C57Bl/6, 2-3 month, n = 5 (filled squares); Ccl2-/-, 2-3 month, n= 6 (open squares); C57Bl/6, 10-12 month, n = 6 (filled triangles), Ccl2-/-, 10-12 month, n= 6 (open triangles)). Amplitudes were obtained from dark adapted mice using standard scotopic Ganzfeld ERG at different light intensities (0.001-10 cds/m2). Note the half logarithmic scale for light intensities. C57Bl/6: continuous lines, Ccl2-/-: intermitted lines. Stars indicate a significant difference in amplitude compared to young C57Bl/6 mice (p <0.05, oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test). Note, that there are no significant differences between age-matched groups.

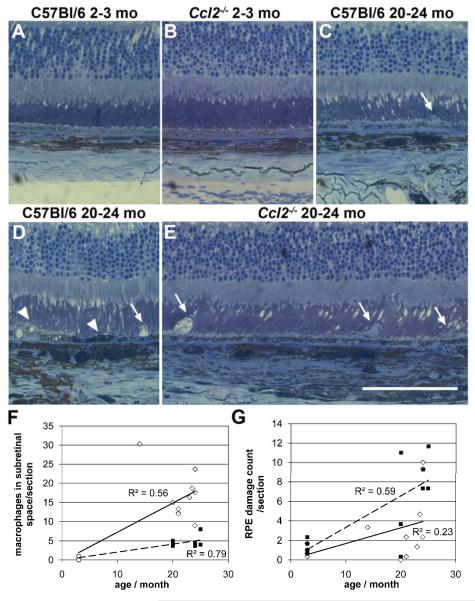

Increased number of subretinal macrophage-like cells

In order to determine the number of macrophage-like cells in the subretinal space and to evaluate RPE damage in a quantitative manner we examined toluidine blue-borax stained semithin histological sections from young (2-3 month) and old (20-24 month) Ccl2-/- and C57Bl/6 wildtype mice (figure 4A-E). This confirmed that significantly more macrophages were present in the subretinal space of 20-24 month old Ccl2-/- mice (n=10) compared with aged-matched controls (n=7) (figure 4C and 4D vs. 4E). In young (2-3 month) mice of both genotypes (MCP-1: n= 5, C57Bl/6: n= 5; figure 4A, 4B) these cells were not observed (oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test, p< 0.01). Furthermore for both genotypes a significant and positive correlation between age and the number of macrophage-like cells in the subretinal space was found (figure 4F;Ccl2-/- Pearson correlation r=0.748, p< 0.01, n=15 and C57Bl/6 mice Pearson correlation r=0.890, p< 0.01, n=12). Interestingly, the macrophages in aged MCP-1 mice were bigger and more swollen than those in old C57Bl/6 mice (white arrows, figure 4C vs. 4G). Between 30 – 50% of these subretinal macrophages in both genotypes showed a prominent accumulation of pigment granules suggesting an uptake of RPE material and thus potentially a diseased RPE. To evaluate this quantitatively, we counted cellular events such as cell lysis, pyknosis, swelling, thinning and thickening of RPE cells from the superior to the inferior end of the retina in each section and calculated the mean sum of RPE alterations per section from 3 sections per animal, which represents a measure for RPE damage following a scheme by Hollyfield et al.20 We compared all four groups (2-3 month old C57Bl/6 (n=5), 2-3 month old Ccl2-/- (n=5), 20-24 month old C57Bl/6 (n=7), and 20-24 month old Ccl2-/- mice (n=10)) and found a significant increase of RPE damage per section with age but no significant difference between Ccl2-/- mice and aged-matched controls (oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test: p< 0.01). Furthermore, we analysed the correlation between age and RPE damage/section combining both genotypes and found a significant, positive correlation between age and RPE changes (Pearson correlation r=0.585, p=0.001, n=27).

Figure 4. Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice do not develop abnormal retinal pigment epithelial changes with age, but do show an accumulation of bloated macrophages in the subretinal space.

Toluidine blue-borax stained semithin histological sections of the outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid from young (2-3 month) and old (20-24 month) Ccl2-/- and C57Bl/6 wildtype mice (A-E). No obvious histological differences between young C57Bl/6 wildtype (A) and Ccl2-/- (B) mice were observed. In old C57Bl/6 (C, D), and in old Ccl2-/- mice (E) photoreceptor morphology was also normal, but macrophage-like cells were observed in the subretinal space. These cells were bigger and swollen in Ccl2-/- mice (C, D vs. E, white arrows). Swelling/lysis of RPE cells and pyknosis (indicated by the darker staining) of RPE cells were observed in senescent animals of both genotypes, but are only shown as examples in C57Bl/6 wildtype mice (D, white arrowheads). Note the higher pigmentation of the choroid in old C57Bl/6 and Ccl2-/- mice compared to young mice (C, D and E vs. A, B). Scale bar A-E: 100 μm.

Quantitative analysis of number of macrophage-like cells in the subretinal space (F). The mean number of macrophages per individual animal is depicted (C57Bl/6, black squares; Ccl2-/- mice open diamonds) and shows a significant positive correlation between age and number of macrophages in the subretinal space per section, which was much more pronounced in Ccl2-/- mice. G: Quantitative analysis of alterations in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The RPE damage count (sum of RPE areas showing cell lysis, pyknosis, swelling, thinning, or thickening of RPE cells per retinal section) for individual animals is shown (Ccl2-/-: continuous line, C57Bl/6: dashed line), revealing a similar accumulation of RPE alterations with age in both genotypes and an overall positive correlation of this accumulation with age (Pearson correlation r=0.585, p=0.001, N=27)

Thus, whilst the accumulation of macrophages in the subretinal space is accelerated and more pronounced in Ccl2-/- mice, age-related RPE changes occur to a similar extent in both Ccl2-/- and wildtype C57Bl/6 mice.

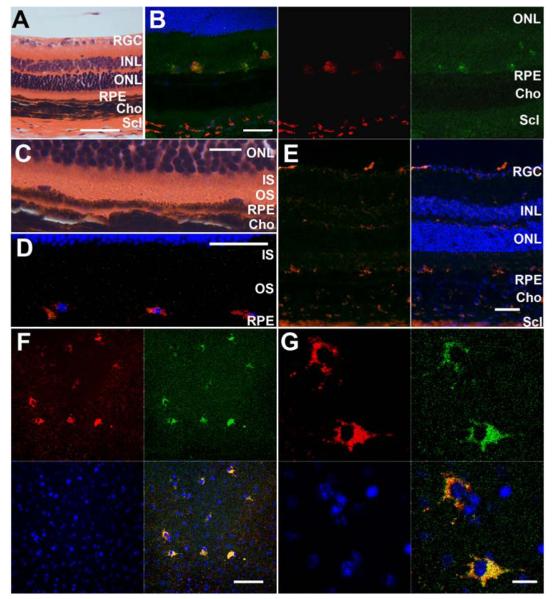

To confirm that the cells in the subretinal space are of the monocyte/macrophage lineage, we used CD68, a marker for activated and phagocytically active marcophages, and the pan-macrophage marker F4/80 and found that the subretinal cells were positive for both of these markers (figure 5A-E).21 We also analysed the autofluorescence in these cells at 488 nm in sections (Figure 5B, red (CD68 stained) versus green (488nm autofluorescence)) and on RPE flatmounts (546 nm (red) and 488 nm (488 nm), figure 5F, 5G) and found that these cells contained autofluorescent material. We measured a mean diameter of macrophages on the apical side of the RPE of 19.83 μm ± 6.73 μm and (using the optic disc as a reference) 17.99 μm ± 4.90 μm for autofluorescent spots from AF-SLO images (table 1). Thus the regular pattern, size and location of the cells indicates that the autofluorescent spots seen in AF-SLO fundus images in senescent Ccl2-/- mice are subretinal macrophages containing autofluorescent material.

Figure 5. CD68/ED1 and F4/80 immunohistochemistry staining showed that cells in the subretinal space are macrophages, which are phagocytically active and do contain autofluorescent material.

A-E: Comparison of H&E histology (A, C) and CD68/ED1 (B, D: CD68: Alexa Fluor- 546 nm (red)) and F4/80 immunohistochemistry (E: F4/80: Alexa Fluor- 546 nm (red)) of sagittal retinal sections from 20-22 month old Ccl2-/- mice. (A) H&E sections of 20-22 month old Ccl2-/- mice showed oval cells in the subretinal space on the apical side of the RPE, which are relatively regularly spaced. Scale bar: 50 μm (B) CD68 immunohistochemsitry confirmed that these cells are activated (phagocytically active) macrophages, which already was suggested by their cell shape. The macrophages contained autofluorescent material (compare the green autofluorescent channel (right image, 488 nm) with the CD68-positive signal (center image, red channel, 546 nm) and the yellow staining in the overlay (left image). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Higher magnification of (A). Scale bar: 10 μm (D) View on the subretinal space from a second old MCP-1 mouse. CD68-positive macrophages are regularly spaced on top of the RPE. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Immunohistochemsitry for the pan-macrophage marker F4/80 further confirms that the observed subretinal cells are macrophages/monocyte lineage. Note the same location of F4/80 postive and CD68 positive cells in the subretinal space. Scale bar: 50 μm. Counter staining in B, D and E with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (F, G) Retinal pigment epithelial flat mount from an old (22 month) Ccl2-/- mouse counter stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Autofluorescence was detected in both the red (546nm) and the green (488nm) channel. (F) Localization of macrophages on the apical site of the RPE flat mount indicated a regular pattern and spacing of these cells in the subretinal space. Scale bar: 50 μm (G) Higher magnification images of macrophages from (F) showed that the autofluorescence derives from inside the cells. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Table 1. Size comparison of macrophages in RPE flat mounts and autofluorescent spots in autofluorescence scaninng laser ophthalmoscopy (AF-SLO) fundus images of old Ccl2-/- mice.

We used the size of the optic disc in confocal and AF-SLO images to calibrate the AF-SLO fundus images and thus determined the mean size ± S.D. of the autofluorescent spots to be 17.99 μm ± 4.90 μm. This shows that these autofluorescent spots have a similar size as macrophages on the apical site of RPE of senescent Ccl2-/- mice, which have a mean diameter of 19.83 μm ± 6.73 μm based on confocal imaging.

| Confocal imaging of RPE flatmounts Macrophage diameter / μm |

Calculated AF-SLO spot size /μm |

|---|---|

| 30.60 | 17.99 |

| 27.79 | 23.99 |

| 21.33 | 17.99 |

| 18.19 | 23.99 |

| 11.73 | 11.99 |

| 12.10 | 11.99 |

| 17.07 | |

| 19.83 ±6.73 | 17.99 ± 4.90 |

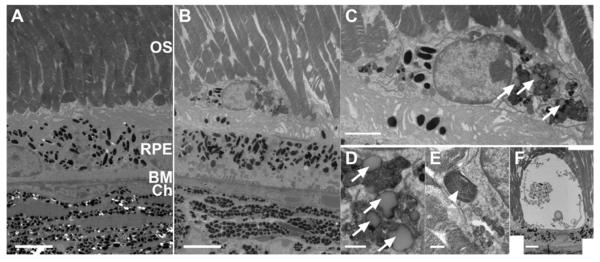

To evaluate the subretinal macrophages and the nature of the autofluorescent material in more detail, we performed ultrastructural analysis using transmission electron microscopy (figure 6). Bloated subretinal macrophages could be seen only in the senescent Ccl2-/- mice (figure 6B) and were located between the apical surface of the RPE and the photoreceptor outer segments. They contained numerous pigment granules (6C), phagosomes and lipofuscin inclusions (figure 6C and 6D, arrows), but only rarely showed phagocytosis of outer segment material (figure 6E, arrow head). While usually the appearance of these cells was suggestive for macrophages (figure 6C), some of these cells seemed to have accumulated a lot of cellular debris and showed a high degree of vacuolization (figure 6F, showing an extreme example, see also figure 4E).

Figure 6. Subretinal Macrophages (SrMC) in old Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice contain pigment granules, phagosomes, lipofuscin, and outer segment (OS) material.

Transmission electron microscopy images obtained from young (2-3 month old mice) and old (20-24 months) C57Bl/6 and Ccl2-/- mice. (A) Representative image for young mice of both genotypes. (B) TEM image from an old Ccl2-/- mouse showing a typical bloated macrophage in the subretinal space and irregular infoldings on the basal side of the RPE. Scale bar for A, B: 5 μm. (C) Higher magnification of a bloated subretinal macrophage containing pigment granules and phagosomes with lipofuscin (arrows). Scale bar: 1 μm. (D, E) Content of bloated subretinal macrophages (SrM), scale bar: 0.5 μm. (D) Phagosomes with lipofuscin inclusions (arrows) were very common. (E) Occasionally outer segment material was observed inside SrMs (arrowhead). (F) Extreme example of a vacuolized cell in the subretinal space, presumably a SrM. Note the healthy underlying RPE, scale bar 5 μm. OS: Outer segments, RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, BM: Bruch’s membrane, Ch: Choroidal vasculature.

Normal age-related chages of Bruch’s membrane (BM)

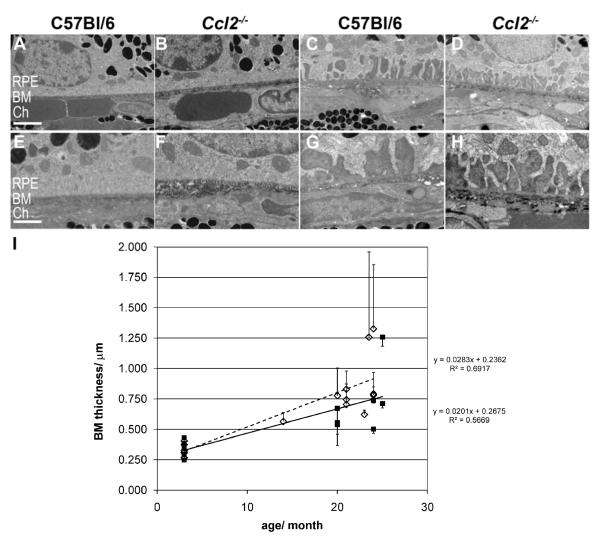

We also evaluated the integrity of the RPE in young (2-3 month) and old (20-24 month) wildtype C57Bl/6 and Ccl2-/- mice at an ultrastructural level and focused in particular on age-related changes at the basal side of the cells and the underlying Bruch’s membrane (figure 7). We observed normal outer segment phagocytosis by the RPE in senescent mice of both genotypes indicating that their RPE is functional and to a certain extent healthy. Nevertheless, with age we found dramatic changes on the basal side of the RPE cells, which were very similar between genotypes (Figure 7A-H). In young animals normal basal infoldings in RPE cells (figure 7A, 7B, higher magnification 7E, 7F), and a normal Bruch’s membrane (BM) with a thickness of about 0.34 μm was observed (table 2). In contrast, aged animals of both genotypes showed wide areas of large basal invaginations filled with amorphous sub-RPE deposits (figure 7C, 7D and 7G, 7H). There were no obvious differences in these deposits between wildtype and MCP-1 mice and no drusen-like structures were identified in either of the two genotypes on the basal side of the RPE. Mean BM thickness for senescent C57Bl/6 mice was 0.71 ± 0.26 μm and for senescent Ccl2-/- mice it was 0.87 ± 0.25 μm (table 2). These values are both approximately twice the values from young animals indicating that the major cause of BM thickening in both genotypes is due to aging. This was further supported by the fact that we did not identify significant differences between aged-matched wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice (table2, oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test p < 0.01). Furthermore, we identified a significant correlation between age and BM thickness in each genotype independently (figure 7I; C57Bl/6: Pearson correlation r=0.753, p < 0.01, n= 12; Ccl2-/-: Pearson correlation r=0.832, p < 0.01, n= 15) further supporting the conclusion that normal aging and not the Ccl2 genotype is the major cause of the increase in sub-RPE deposits and BM thickness.

Figure 7. Age-related ultrastructural changes of the RPE and Bruch’s Membrane (BM) in Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) and wildtype mice.

(A-H) Transmission electron microscopy images of RPE, Bruch’s membrane (BM), and choroidal interface at two different magnifications, scale bars A-D: 2 μm; E-H: 1 μm. Young mice (A, B, E, F): Normal basal infoldings of RPE cells and normal appearance of BM in both genotypes. Senescent mice (C, D, G, H): In both genotypes areas of irregular, and big basal invaginations in RPE cells with amorphous sub-RPE deposits were observed. I: Quantitative assessment of BM thickness with age for C57Bl/6 (black squares, black line) and Ccl2-/- mice (open diamond, intermitted line). BM thickness is shown for individual animals as a mean ± S.D. of measures taken in the superior and inferior hemisphere. R2 values and the respective equations for the linear regression between age and BM thickness are shown for each genotype. There was a significant correlation between age and BM thickness in both genotypes. C57Bl/6 (Pearson correlation r=0.753, p < 0.01, n= 12), Ccl2-/- (Pearson correlation r=0.832, p < 0.01, n=15) but no significant difference between aged-matched Ccl2-/- vs. C57Bl/6 mice (oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test, for details see table 2). RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, BM: Bruch’s membrane, Ch: Choroidal vasculature.

Table 2. Quantitative ultrastructural analysis of Bruch’s membrane (BM) thickness.

Mean BM thickness ± S.D. per group of animals according to genotype and age. Data for the 14 month old Ccl2-/- animal as seen in figure 7 is here excluded.

| 2-3 month C57Bl/6 (1) | 2-3 month Ccl2-/- (2) | 20-24 month C57Bl/6 (3) | 20-24 month Ccl2-/- (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM thickness ± S.D. / μm |

0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.71 ± 0.26 | 0.87 ± 0.25 |

| N (animal) | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| Oneway ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test (overall p<0.001) |

1 vs. 2: p=1.0 1 vs. 3: p=0.032 1 vs. 4: p=0.001 |

2 vs. 1 : p= 1.0 2 vs. 3: p=0.029 2 vs. 4: p=0.001 |

3 vs. 1: p=0.032 3 vs. 2:p=0.029 3 vs. 4:p=0.819 |

4 vs. 1: p=0.003 4 vs. 2: p=0.031 4 vs. 3: p=0.819 |

Reduced laser induced CNV lesion size in Ccl2 knockout mice

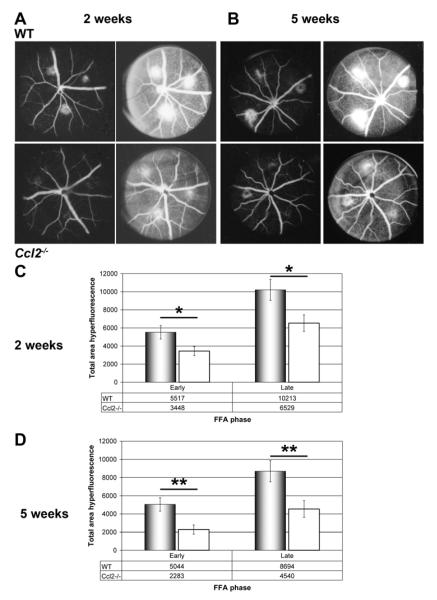

In a previous study a higher susceptibility to spontaneous CNV development has been described in Ccl2-/- mice.9 Four out of 15 Ccl2-/- mice aged older than 18 month have been reported to develop CNV with clear evidence of vascular leakage and subsequent morphological alterations at the ultrastructural level. In this study, however, we did not observe indications for a spontaneous CNV development in 11 senescent Ccl2-/- mice between 16 and 25 month of age. We used fundus fluorescein angiography (n=5, 16 months) and lectin stained RPE and retinal flat mounts (n=6, 23-25 months) to specifically study CNV development and did not observe any signs of CNV (data not shown). Furthermore our morphological analyses at the histological and ultrastructural levels also did not reveal any CNV-associated morphological alterations in a further 15 senescent Ccl2-/- mice age 20-25 months (figures 2, 4, 6 and 7). In order to evaluate the susceptibility of Ccl2-/- mice to CNV we therefore analysed the neovascular response after laser photocoagulation using fundus fluorescein angiography. By this, we observed a 45 – 64% reduction in the area of hyperfluorescence in Ccl2-/- mice in both the early and the late phase of the angiography at 2 and 5 weeks after laser (figure 8A-D), which indicated that the lack of the CC-cytokine ligand 2/MCP-1 leads to a reduced choroidal neovascular response after laser-injury.

Figure 8. In vivo fundus fluorescein angiography two and five weeks after photocoagulation/laser induced chroidal neovascularisation (CNV) revealed areduced vessel leakiness in CNV- lesions of Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice.

Representative images of early (90 sec) and late (7min) phase fundus fluorescein angiography (A, B). The images show CNV lesions from C57Bl/6 wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice at two (A) or five (B) weeks after lasering. In Ccl2-/- mice, the area of hyperfluorescence was smaller compared to that in wildtype animals. Thus a reduced neovascular response in Ccl2-/- mice was indicated. (C) Quantitative analysis of CNV lesion size in vivo at two weeks (C) and five weeks (D) after lasering confirmed the qualitative result obtained from the angiograms (A, B). Stars indicate significant reduction in CNV lesion size in Ccl2-/- mice compared to C57Bl/6 mice (Two-tailed T-test *p<0.05; ** p<0.01). Hyperfluorescent area is given in arbitrary units.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that the drusen-like phenotype in Ccl2 knockout (Ccl2-/-) mice is not caused by sub-RPE deposits, but is due to the accelerated age-related accumulation of bloated macrophages in the subretinal space. These cells contain autofluorescent material, in particular lipofuscin, and they almost certainly account for the autofluorescent spots in AF-SLO images. We also observed a similar, but not as pronounced accumulation of macrophages during aging in normal mice and thereby confirmed recent findings by Xu et al., who showed an age-dependent accumulation of subretinal microglia.22 Together with our findings this indicates that the accumulation of macrophages/microglia in the subretinal space is a normal age-related process which is accelerated in Ccl2-/- mice. Therefore, MCP-1/CCL2–CCR2 signaling is not only important for the recruitment of monocytes to sites of inflammation,6 but also plays a role for of the trafficking of microglia/macrophages during aging. In the absence of MCP-1, macrophages seem to be less capable of leaving the subretinal space after uptake of cellular debris, and continue to degrade it to autofluorescent material including lipofuscin and finally vacuolize. A similar process has been reported for the development of foam cells in artherosclerotic plaques.23

Further support for the role of cytokines in maintaining macrophage migration and mobility during aging comes from recent findings in another cytokine receptor mouse model, the Cx3cr1 knockout, which shows a very similar accelerated accumulation of subretinal microglia/macrophages.11 Lipid-bloated microglia are the origin of the drusen-like appearance in CX3CR1 deficient mice.13 It has been suggested that these cells can leave the subretinal space via two different routes, the choroidal or the inner retinal circulation. CD68-positive microglia/macrophages double labeled with rhodopsin antibodies have been observed in the inner retina and in the choroid, suggesting that microglia may invade the subretinal space, clear up cellular debris such as outer segment material and then leave the subretinal space either via the inner retinal vasculature or the choroid.24 Thus, CCL2 or CX3CR1 deficiencies both seem to lead to a similar accumulation of cells from the monocyte/microglia/macrophage lineage in the subretinal space with age causing a macroscopically similar drusen-like phenotype. However, there seem to be distinct differences between these cytokine pathways. While in bloated subretinal microglia of the Cx3cr1 knockout model, multiple lipid droplets were observed,13 this distinct ultrastructural feature was not prominent in bloated subretinal cells of Ccl2-/- mice. We observed lipofuscin accumulation and in 30-50% of the cells, pigment granules as the most prominent intracellular components. This raises the possibility that different subtypes of F4/80 and CD68-positive phagocytically active cells are accumulating in the two knockout models. Further support for the different roles of the MCP-1/CCR2 signaling and the CX3CR1 mediated signaling in the eye comes from the different responses to laser-induced choroidal neovascularisation in the respective knockout models. In this study we observed a reduction of CNV lesions size and thus a reduced angiogenic response in Ccl2-/- knockout mice at two and five weeks after photocoagulation. Furthermore, we did not observe any spontaneous development of CNV in senescent Ccl2-/- mice. These observations were in contrast to the higher susceptibility of aged Ccl2-/- mice to spontaneous CNV,9 but were consistent with previous observations in the Ccr2 knockout mouse line, which also showed a reduced response to laser-induced CNV suggesting that CCL2 acts via CCR2 during laser-induced CNV promoting neovascular responses.25 In contrast to these findings, Cx3cr1 knockout mice showed an exacerbated response to laser-induced CNV two weeks after photocoagulation highlighting the different roles of the two monocyte recruiting signaling pathways during the CNV response.11 CCL2 actively recruits a subset of pro-inflammatory blood monocytes (CX3CR1low, CCR2 postive, Gr1 positive) to sites of inflammation and appears to be important for the angiogenic response during laser-induced CNV. CX3CR1 dependent signaling on the other hand, seems to have an antagonistic role by recruiting a second subset of anti-angiogenic monocytes (CX3CR1 high, CCR2 negative, Gr1 negative) to non-inflamed tissue.24 These CX3CR1 positive monocytes are also thought to have homeostatic roles and to be involved in establishing the resident microglia populations in the eye with a turnover rate of about 6 months, which may, after activation, also be recruited to sites of laser injury.11, 26

In contrast to a previous report on Ccl2-/- mice, 9 our study did not reveal an outer retinal degeneration in Ccl2-/- compared with wildtype mice. Instead we observed a normal age-related decline in number of photoreceptor nuclei and ERG function, confirming that Ccl2-/- mice do not show a higher level of photoreceptor degeneration than wildtype mice. A similar observation was made during our quantitative histological analysis of the RPE, which revealed an indistinguishable age-related increase in RPE damage in both genotypes and therefore no increased RPE atrophy in Ccl2-/- mice. We applied a RPE pathology grading system developed for the CEP-aduct immunized mouse model, in which oxidation-induced inflammation leads to an RPE pathology similar to AMD.20 In our study we found that the level of age-related damage observed in both, C57Bl/6 wildtype and Ccl2-/- mice would only be graded as minor pathology, further supporting the conclusion that there is no major RPE atrophy in Ccl2-/- mice, but rather normal and similar age-related changes in both genotypes.

In ultrastructural histological analyses of Bruch’s membrane we did observe an age-related accumulation of an amorphous, electron dense material in interdigitations on the basal site of the RPE which appeared to be similar to basal laminar deposits found in aged human eyes with early age-related macular degeneration.27 However, the findings did not differ significantly between Ccl2-/- and wild-type mice, confirming that the accumulation of electron dense material is a normal age-related process. Sub-RPE deposits similar to those seen in 20-25 month old mice in this study have also been described in Collagen XVIII/endostatin knockout mice at the age of 16 months. Thus one might speculate that ColXVII/ endostatin or its altered production may play a role in this age-related matrix deposition.28

Overall these findings indicate that most of the previously described hallmark features of age-related macular degeneration in Ccl2 and Ccr2 knockout mice,9 may be explained by normal aging and thus argue against the usefulness of these mouse models as animal models to evaluate treatments for AMD. Nevertheless our data emphasize the importance of the MCP-1-CCR2 signaling not only for the extent of choroidal neovascularisation, a major complication in AMD29 , but also for the maintenance of normal monocyte/macrophage trafficking during aging.

Acknowledgments

Grant information: Moorfields Eye Hospital/ Institute of Ophthalmology NIHR BMRC; The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, The Health Foundation, Royal Blind and the Scottish National Institution for the War Blinded

References

- 1.Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL. Causes of visual impairment in people aged 75 years and older in Britain: an add-on study to the MRC Trial of Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:365–370. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.019927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Strategies. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2003;48:257–293. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Chong NH Victor, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An Integrated Hypothesis That Considers Drusen as Biomarkers of Immune-Mediated Processes at the RPE-Bruch’s Membrane Interface in Aging and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2001;20:705–732. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullins RF, Russell SR, Anderson DH, Hageman GS. Drusen associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease. FASEB J. 2000;14:835–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, et al. From the Cover: Drusen proteome analysis: An approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. PNAS. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, et al. Abnormalities in Monocyte Recruitment and Cytokine Expression in Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1-deficient Mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuziel WA, Morgan SJ, Dawson TC, et al. Severe reduction in leukocyte adhesion and monocyte extravasation in mice deficient in CC chemokine receptorá2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94:12053–12058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boring L, Gosling J, Chensue SW, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, et al. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuo J, Smith BC, Bojanowski CM, et al. The involvement of sequence variation and expression of CX3CR1 in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J. 2004:04–1862fje. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1862fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combadiere C, Feumi C, Raoul W, et al. CX3CR1-dependent subretinal microglia cell accumulation is associated with cardinal features of age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2920–2928. doi: 10.1172/JCI31692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despriet DDG, Bergen AAB, Merriam JE, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of the Candidate Genes CCL2, CCR2, and TLR4 in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:364–371. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raoul W, Feumi C, Keller N, et al. Lipid-bloated subretinal microglial cells are at the origin of drusen appearance in CX3CR1-deficient mice. Ophthalmic Res. 2008;40:115–119. doi: 10.1159/000119860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, et al. Abnormalities in Monocyte Recruitment and Cytokine Expression in Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1-deficient Mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeliger MW, Beck SC, Pereyra-Munoz N, et al. In vivo confocal imaging of the retina in animal models using scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Vision Research. 45:3512–3519. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.08.014. 5 A.D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffey PJ, Gias C, McDermott CJ, et al. Complement factor H deficiency in aged mice causes retinal abnormalities and visual dysfunction. PNAS. 2007;104:16651–16656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705079104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Ruckmann A, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. Distribution of fundus autofluorescence with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:407–412. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.5.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luhmann UFO, Lin J, Acar N, et al. Role of the Norrie Disease Pseudoglioma Gene in Sprouting Angiogenesis during Development of the Retinal Vasculature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3372–3382. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balaggan KS, Binley K, Esapa M, et al. EIAV vector-mediated delivery of endostatin or angiostatin inhibits angiogenesis and vascular hyperpermeability in experimental CNV. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1153–1165. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollyfield JG, Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, et al. Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2008;14:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramprasad M, Terpstra V, Kondratenko N, Quehenberger O, Steinberg D. Cell surface expression of mouse macrosialin and human CD68 and their role as macrophage receptors for oxidized low densityálipoprotein. PNAS. 1996;93:14833–14838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H, Chen M, Manivannan A, Lois N, Forrester JV. Age-dependent accumulation of lipofuscin in perivascular and subretinal microglia in experimental mice. Aging Cell. 2007;7:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bobryshev YV. Monocyte recruitment and foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. Micron. 2006;37:208–222. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raoul W, Keller N, Rodero M, Behar-Cohen F, Sennlaub F, Combadiere C. Role of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 in the mobilization of phagocytic retinal microglial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;198:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsutsumi C, Sonoda KH, Egashira K, et al. The critical role of ocular-infiltrating macrophages in the development of choroidal neovascularization. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:25–32. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu H, Chen M, Mayer EJ, Forrester JV, Dick AD. Turnover of resident retinal microglia in the normal adult mouse. Glia. 2007;55:1189–1198. doi: 10.1002/glia.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Schaft TL, Mooy CM, de Bruijn WC, Bosman FT, de Jong PT. Immunohistochemical light and electron microscopy of basal laminar deposit. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994;232:40–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00176436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marneros AG, Keene DR, Hansen U, et al. Collagen XVIII/endostatin is essential for vision and retinal pigment epithelial function. EMBO J. 2004;23:89–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]