Abstract

Ethanol has been suggested to elevate HCV titer in patients and to increase HCV RNA in replicon cells, suggesting that HCV replication is increased in the presence and absence of the complete viral replication cycle, but the mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we use Huh7 human hepatoma cells that naturally express comparable levels of CYP2E1 as human liver to demonstrate that ethanol, at subtoxic and physiologically relevant concentrations, enhances complete HCV replication. The viral RNA genome replication is affected for both genotypes 2a and 1b. Acetaldehyde, a major product of ethanol metabolism, likewise enhances HCV replication at physiological concentrations. The potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol is suppressed by inhibiting CYP2E1 or aldehyde dehydrogenase and requires an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio. In addition, acetate, isopropyl alcohol, and concentrations of acetone that occur in diabetics enhance HCV replication with corresponding increases in the NADH/NAD+. Furthermore, inhibiting the host mevalonate pathway with lovastatin or fluvastatin and fatty acid synthesis with 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid or cerulenin significantly attenuates the enhancement of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetone, as well as acetate, whereas inhibiting β-oxidation with β-mercaptopropionic acid increases HCV replication. Ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetone, and acetate increase the total intracellular cholesterol content, which is attenuated with lovastatin. In contrast, both endogenous and exogenous ROS suppress the replication of HCV genotype 2a, as previously shown with genotype 1b. Conclusion: Therefore, lipid metabolism and alteration of cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio are likely to play a critical role in the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol rather than oxidative stress.

Keywords: Metabolism/Alcohol, Metabolism/Cholesterol, Metabolism/Lipogenesis, Oxygen/Reactive, Viruses/Hepatitis, Viruses/Replication, CYP2E1

Introduction

Ethanol consumption is a well-known risk factor for chronic liver diseases. Ethanol is also a key cofactor in the pathogenesis induced by hepatitis C virus (HCV),2 and it decreases the efficacy of anti-HCV treatments (1, 2). Likewise, HCV infection exacerbates liver damage caused by prolonged alcohol abuse (2). It has also been reported that patients with a history of alcohol abuse are more likely to be infected with HCV than the rest of the population (1).

In addition, ethanol has been suggested to exacerbate HCV-induced liver diseases in part by affecting the viral titer (2–5). Hepatitis C patients who drink alcohol typically show a pattern of hepatic injury that is more characteristic of chronic viral hepatitis than alcohol-induced injury, suggesting that alcohol enhances the pathogenic effects of HCV rather than exerting its independent effects on liver (6). Several clinical studies have correlated increased serum and intrahepatic HCV titer with the amount of alcohol consumed (2, 4, 5). Abstinence or moderation of alcohol consumption could reduce the HCV titer in some patients (2, 5). Furthermore, in vitro studies suggest that ethanol increases HCV RNA levels in Huh7 human hepatoma replicon cell lines that continuously support the HCV RNA replication without virus production (3, 7, 8). These studies suggest that ethanol enhances HCV replication both in the presence and absence of the complete viral replication cycle. HCV replicon systems and more recent virus-producing cell culture models have increased our understanding of HCV and provide us with tools for studying potential interactions between HCV and pathological cofactors, such as ethanol (9).

Nevertheless, whether ethanol directly enhances HCV production in the context of the complete viral replication cycle has not been demonstrated. Furthermore, the mechanism by which ethanol modulates HCV RNA replication remains controversial as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation products, which can be generated during ethanol metabolism, can suppress, rather than increase, HCV RNA replication in cells, suggesting the involvement of other metabolites of ethanol (10–14). Oxidative hepatic ethanol metabolism is a multistep process (4). Alcohol dehydrogenase, the predominant ethanol-metabolizing enzyme, is found in the cytosol and produces acetaldehyde and NADH. Ethanol-inducible cytochrome P450 (CYP2E1), which is induced during extended ethanol exposure, is another major ethanol-metabolizing enzyme located in the endoplasmic reticulum and generates NADP+ and ROS in addition to acetaldehyde. Catalase, which is found in peroxisomes, is thought to not contribute significantly to ethanol metabolism under normal conditions. Once ethanol is metabolized into acetaldehyde, it is rapidly converted into acetate and NADH by aldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde and other products of ethanol metabolism have been implicated in many pathogenic effects of ethanol. Whether these metabolites also participate in the modulation of HCV replication by ethanol, however, has not yet been tested.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to determine the effects of ethanol exposure on HCV replication in the context of the complete HCV replication cycle and the mechanisms, comparing the effects of other metabolites of ethanol with those of ROS. Our data show that ethanol and acetaldehyde, at subtoxic and physiologically relevant concentrations, elevate complete HCV replication, as opposed to the suppression caused by endogenous and exogenous ROS. Our data further suggest that elevation of the ratio of NADH/NAD+ and modulation of lipid metabolism are likely to play critical roles in the modulation of HCV replication by ethanol. Possible implications on in vivo HCV replication, patient education, and disease management are also discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

HCV Constructs

The genotype 2a HCV constructs, pJFH1 (produces infectious virus particles), replicative-null pJFH1-GND, and subgenomic pSgJFH1-Luc (contains a luciferase reporter gene), are described elsewhere (15, 16). Huh7 cell clones (SgPC2 and Clone B) supporting continuous replication of a subgenomic HCV replicon of genotype 1b (Con1 sequence) were also used (11, 17). The subgenomic replicons support HCV RNA replication but no virus is formed.

HCV RNA Transfection, Infection, and Cell Culture

The in vitro transcription, transfection of HCV RNA, and Huh7 human hepatoma cell culture were performed as described (10, 11). For the in vitro infectivity assays, 2 ml of the extracellular medium from JFH1 RNA-transfected cells were used to inoculate naïve Huh7 or Huh7.5 cells with 3 ml of fresh medium, as described (16, 18). Treatments were initiated 24 h after infection, and the cells were harvested after another 24 or 48 h.

Northern Blot Analysis

Intracellular RNA extraction and Northern blots were carried out, as described (10, 11). DNA probes were prepared from nucleotides (nt) 4128–8273 or 358–2816 of JFH1, generated with ScaI and ApaL I, respectively, or 3669 to 6016 of the Con1 subgenomic replicons. Images were quantified by densitometry, using Optiquant Cyclone 4.00 (Perkin Elmer), and data were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA content.

Quantitative Real-time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

The total intracellular RNA was obtained from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen). To obtain extracellular HCV RNA, cell culture medium samples were first treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature, then RNA was extracted using TRIzol LS, and glycogen as a carrier. HCV RNA was quantified by qRT-PCR as described (11, 16). The primer sequences for JFH1 were 5′-TCTGCGGAACCGGTGAGTA-3′ (nt 146–164; forward), and 5′-TCAGGCAGTACCACAAGGC-3′ (nt 277–295; reverse), and the sequence of the fluorogenic probe, labeled with 6-FAM and TAMRA (Biosearch Technologies, Inc.), was 5′-CCAGTCTTCCCGGCAATTCCG-3′ (nt 168–188). Standard curves were generated using in vitro transcribed HCV RNA. Intracellular HCV RNA levels were normalized by 18 S rRNA or GAPDH mRNA.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were sonicated in Laemmli buffer, and proteins were analyzed for NS5A and β-actin by Western blot, as described (10). Loading was normalized by protein assay of acetone-precipitated proteins determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce). Quantification of Western blots was performed by densitometry using the Kodak IS2000R software.

Luciferase Assays

After various treatments, SgJFH1Luc RNA-transfected cells were lysed with 1× Reporter Lysis Buffer, and the luciferase activity was determined using Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega) (15). Luciferase activities were normalized by total protein content, determined with bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce).

In Vitro HCV Replication Assay

In vitro replication assay was carried out, as previously described (10, 11). Briefly, cytoplasmic lysates were prepared, and the replication was allowed to proceed for 1 h at 30 °C in the presence of [α-32P]CTP and actinomycin D. Then, RNA products were analyzed on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel, which was subsequently analyzed, using Optiquant Cyclone 4.00 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

CYP2E1 Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)

Huh7 and SgPC2 cells were transfected with 50 nm CYP2E1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or non-targeting control (Dharmacon) siRNAs, using RNAiMax (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's recommendations.

CYP2E1 Activity Assay

Cells were treated with and without 0.2% ethanol for 48 h and lysed. CYP2E1 activity was determined by measuring hydroxylation of p-nitrophenol as described, except NADPH, instead of the NADPH-generating system, was used (19). The specificity was demonstrated by inhibiting the reaction with 100 μm CYP2E1 antibodies, and portion of the activity that is inhibited by CYP2E1 antibodies was then calculated and reported.

NADH/NAD+, Cholesterol, and ATP Assays

NADH and NAD+ levels were determined by enzymatic NADH recycling assay, using the NAD+/NADH Quantification kit from Biovision, per the manufacturer's recommendations. After various treatments, cells were collected in 400 μl of NADH/NAD+ extraction buffer. Samples were immediately subjected to two freeze/thaw cycles and filtered using Microcon YM-10 (Millipore). Then, the samples were split into two sets, one of which was used to carry out the thermal decomposition of NAD+ followed by the cycling assay for the determination of NADH content of the cell. The other set was used to measure the total NADH plus NAD+ content by performing the cycling assay without the thermal decomposition. Then, the NADH/NAD+ ratio was calculated. Total intracellular cholesterol was measured using the Cholesterol/Cholesteryl Ester Quantitation kit (Biovision) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were homogenized in chloroform/isopropyl alcohol/Triton X-100 (7:11:0.1). The lipids were extracted, and all traces of organic solvents were evaporated prior to resuspending the lipids in the reaction buffer and performing the assay. Total ATP content was measured using Somatic Cell ATP Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The data were normalized by total protein content, determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance, using SigmaStat 3.1 (Jandel Scientific). A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All experiments were repeated three to six times, and either the means ± S.E. of several independent experiments or the representative Northern or Western blot images are shown.

RESULTS

Ethanol Increases the Complete Replication of HCV at Physiological Concentrations

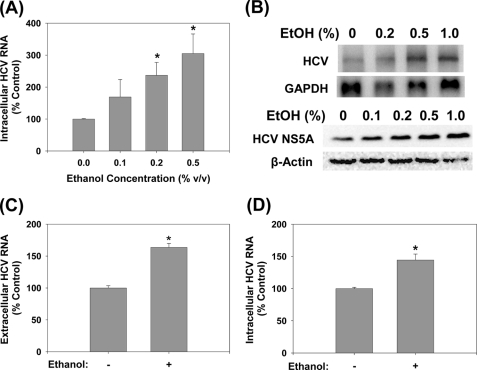

To examine whether ethanol increased the complete replication of HCV, positive-sense genomic JFH1 RNA was produced by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase and transfected into Huh7 human hepatoma cells. Then, the transfected cells were exposed to 0–1.0% (v/v, 0–172 mm) ethanol once daily for 48 h. Then, the cells and the cell culture medium were harvested and analyzed for intracellular and RNase A-resistant extracellular HCV RNAs by a combination of Northern blots and qRT-PCR. Ethanol significantly increased the intracellular JFH1 HCV RNA levels to 237 ± 40 and 305 ± 61% of untreated controls at 0.2 and 0.5% concentrations, respectively (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1, A and B, top panel). HCV NS5A protein level similarly increased with ethanol treatments (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). Extracellular HCV RNA was also significantly elevated with the 0.2% ethanol treatment, indicating increased virus secretion (Fig. 1C). Next, we examined whether virus-infected cells responded similarly to ethanol treatment with elevated HCV RNA. We found that 0.2% ethanol also increased HCV RNA in Huh7 cells infected with cell culture-generated JFH1 virions (Fig. 1D). JFH1 GND mutant, which harbors a critical mutation (GDD:GND) in NS5B, the viral polymerase, did not replicate or generate infectious virus particles, as expected (data not shown). These concentrations of ethanol did not induce any cytotoxicity, as assessed by cell morphology and measuring the ATP content (data not shown). The 0.2% ethanol, equivalent to blood alcohol concentration of 34.4 mm, that significantly enhanced HCV replication, is approximately twice the legal limit for driving under the influence in many countries, including the United States. The 0.5% ethanol lies in the toxic range but can also be achieved physiologically, particularly in chronic alcohol users. In addition, ethanol is volatile, and the amount that remains would be significantly less than what was added to cell culture medium (20). These data, therefore, suggest that ethanol can enhance complete HCV replication, at physiologically attainable concentrations.

FIGURE 1.

Ethanol increases JFH1 replication. Huh7 cells transfected with JFH1 RNA were analyzed for intracellular HCV RNA by (A) qRT-PCR (n = 6) or (B) Northern blots (n = 4) and for HCV NS5A protein content by Western blot (n = 3) (B, bottom panel) after 48 h of ethanol treatments. C, extracellular HCV RNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for 0.2% ethanol treatments (n = 4). D, naïve Huh7 cells were inoculated with virus-containing medium and analyzed for HCV RNA after 48 h of 0.2% ethanol treatment (n = 4). *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

Ethanol Enhances HCV RNA Replication of Genotypes 2a and 1b

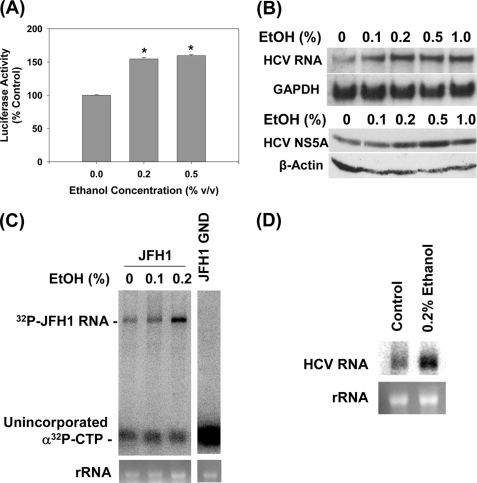

Previously, ethanol was shown to elevate HCV RNA content in Huh7 cells that supported subgenomic HCV RNA replication without virus production (3, 7, 8). To test whether the JFH1 RNA replication was also affected by ethanol, we transfected Huh7 cells with SgJFH1-Luc RNA and exposed the cells to ethanol for 48 h. Then, HCV replication was monitored by measuring the firefly luciferase activity (15). Ethanol increased the luciferase activity in these cells, suggesting that the JFH1 RNA genome replication was affected (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Ethanol increases the replication of subgenomic JFH1 and Con1 replicon RNAs. A, Huh7 cells transfected with SgJFH1-Luc RNA were analyzed for luciferase activity after 48-h ethanol treatments (n = 3). B, stable Huh7 clones expressing SgCon1-Neo (SgPC2) were incubated with ethanol for 24 h and analyzed for HCV RNA, GAPDH mRNA, and NS5A and β-actin proteins (n = 3) by Northern and Western blots, respectively (n = 3). C and D, cytosolic lysates were prepared from (C) JFH1 and JFH1-GND RNA-transfected cells and (D) SgPC2 cells, after 5 h of ethanol treatment, these lysates were used to carry out in vitro replication assays (n = 3). Bottom panels show ethidium bromide staining of rRNA as the loading control. *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

Genotype 2a HCV infection is found globally, with the prevalence ranging from less than 2 to about 30% depending on the geographical region (21, 22). However, as the most prevalent HCV genotype is genotype 1, we also repeated these experiments, using Con1 subgenomic replicon (SgPC2) cells (11, 17). Again, significant increases in the genotype 1b HCV RNA could be demonstrated with 0.1–1% ethanol (Fig. 2B, top panel). Similar increases in the HCV NS5A protein content was demonstrated by Western blots (Fig. 2B, bottom panel).

To confirm that the rate of the HCV RNA genome replication is accelerated by ethanol, we measured the activity of the HCV RNA replication complex. JFH1-transfected cells were exposed to ethanol for 5 h and then, the cytoplasmic lysates, containing the HCV replication complex, were isolated. Then, the in vitro RNA replication assay was performed in the presence of α-32P-labeled CTP and actinomycin D, as previously described (11). JFH1 cell extracts produced a single band that corresponded to the expected size of the HCV RNA, indicating active viral RNA replication, whereas the JFH1 GND extracts did not (Fig. 2C). Ethanol significantly increased the rate of HCV RNA replication (Fig. 2C). Ethanol also accelerated the in vitro replication rate of Con1 strain (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, ethanol did not increase the HCV internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) activity, as assessed by the HCV IRES activity assay, using pRL-HL (data not shown) (23). The data suggest that ethanol increases the rate of HCV RNA replication without directly enhancing its translation rate, at least when these processes are evaluated separately. Therefore, increases in the NS5A protein content with ethanol (Fig. 2B) are likely to have resulted from increased levels of the viral RNA template available for translation.

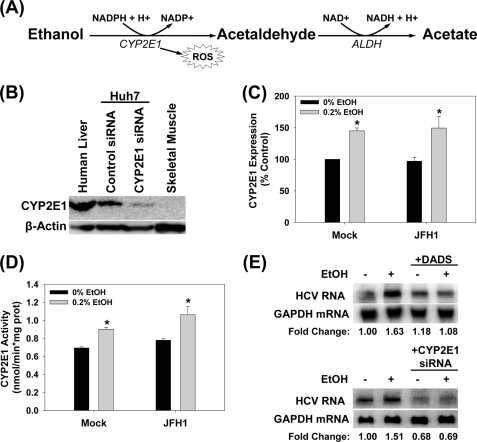

CYP2E1 Is Present in Huh7 Cells at Significant Levels as in Human Liver

Next, we started examining the mechanism by which ethanol increased HCV replication, first, by identifying key steps of ethanol metabolism that mediated this effect (Fig. 3A). Alcohol dehydrogenase I was not detected in significant levels in our Huh7 cells (data not shown). To confirm that ethanol metabolism is occurring in our cells, we then analyzed our Huh7 cells for the expression of CYP2E1. Our Huh7 cells expressed significant levels of CYP2E1 protein, which was about 2.2 ± 0.5-fold less than human liver (Fig. 3B). CYP2E1 expression could also be enhanced by 1.5 ± 0.2-fold with daily treatment with 0.2% (v/v) ethanol for 48 h (Fig. 3C). This enhanced expression of CYP2E1 could be maintained for at least 2 weeks. The CYP2E1 activities (Fig. 3D) were within the expected range for human liver, which is 0.25–3.3 nmol/min/mg protein, and paralleled the CYP2E1 expression levels (Fig. 3C) (19). CYP2E1 activity of human liver shown in Fig. 3B was 1.83 ± 0.01 nmol/min/mg. Con1 SgPC2 cells had similar expression and activity levels of CYP2E1 as Huh7 cells (0.81 ± 0.02 nmol/min/mg without ethanol; 1.01 ± 0.06 nmol/min/mg with 0.2% ethanol).

FIGURE 3.

CYP2E1 expression in Huh7 cells. A, CYP2E1-dependent ethanol metabolism. B, human liver tissue, Huh7 cells transfected with 50 μm non-targeting control or CYP2E1 siRNA, and skeletal muscle tissue were analyzed for CYP2E1 protein content by Western blot (n = 3). C and D, mock- or JFH1-transfected Huh7 cells were incubated with or without 0.2% (v/v) ethanol for 48 h and analyzed for (C) CYP2E1 expression by Western blot (n = 3) and (D) CYP2E1-dependent p-nitrophenol hydroxylation activity (n = 3). E, SgPC2 cells were exposed to 0.2% ethanol ± 25 μm DADS for 24 h or transfected with 50 nm control or CYP2E1 siRNA for 24 h and then incubated with ethanol for 24 h and analyzed for HCV RNA by Northern blot (n = 3). *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

The ethanol-induced potentiation of HCV replication could be abrogated with 25 μm diallyl disulfide (DADS), an inhibitor of CYP2E1 (Fig. 3E). In addition, CYP2E1 siRNA, which decreased CYP2E1 protein level to 35 ± 9% (p < 0.05) of the controls transfected with non-targeting control siRNA, also significantly blunted the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that ethanol is being metabolized by these cells, and that CYP2E1 activity is critical for the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol in our system.

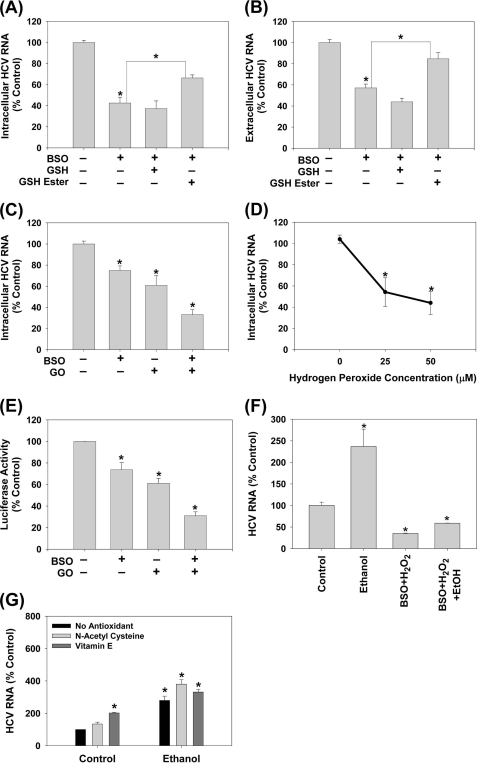

ROS Suppresses JFH1 Replication

Hepatic ethanol, particularly CYP2E1-mediated, metabolism generates ROS in addition to acetaldehyde (24) (Fig. 3A) and previously, we showed that ROS could suppress subgenomic Con1 and H77c/Con1 hybrid HCV RNA replication in these cells (10, 11). To resolve these seemingly conflicting observations, we continued to examine how ROS affected JFH1. To examine the effects of endogenously generated ROS, we first used l-buthionine S,R-sulfoximine (BSO). BSO depletes glutathione (GSH), a major endogenous antioxidant, by inhibiting its de novo synthesis. Therefore, BSO would amplify the effects of endogenous ROS, generated during normal cellular metabolism and in response to HCV (4). BSO decreased intracellular GSH content by ∼80 ± 12% in Huh7 cells (p < 0.05). In addition, BSO decreased both intracellular and extracellular JFH1 RNA levels (Fig. 4, A and B). To confirm that BSO was acting specifically by decreasing GSH, cells were treated with BSO and GSH ethyl ester, which enters cells and is cleaved by cellular esterases to restore GSH inside cells, bypassing the inhibition of GSH biosynthesis by BSO. GSH ethyl ester partially restored both intracellular and extracellular HCV RNA (Fig. 4, A and B). Adding extracellular GSH, which is broken down into its constituents, then taken up for intracellular de novo GSH synthesis, and does not bypass the BSO-inhibited step, could not restore the HCV RNA level in these cells, as expected. The data suggest that BSO decreases HCV replication specifically by decreasing GSH.

FIGURE 4.

Endogenous and exogenous ROS suppress HCV replication. JFH1-transfected Huh7 cells were treated with BSO with and without 2 mm GSH or GSH ester (A and B) (n = 3), GO + glucose with and without 16 h of pretreatment with 20 μm BSO (C) (n = 4), or bolus H2O2 (D) (n = 4) for 24 h. Then, JFH1 intracellular (A, C, D) and extracellular (B) HCV RNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. E, Huh7 cells transfected with SgJFH1-Luc RNA were assayed for luciferase activity after 24 h treatment with 0.25 milliunits/ml glucose oxidase + glucose with and without the BSO pretreatment (n = 3). F, SgPC2 cells were treated with 0.2% ethanol ± H2O2 plus BSO for 24 h, and analyzed for HCV RNA and GAPDH mRNA by Northern blot. G, SgPC2 cells were treated for 24 h with ethanol ± 5 mm NAC or 0.5 μm Trolox (water-soluble vitamin E). Then, HCV RNA and GAPDH mRNA levels were monitored by Northern blot and quantified by densitometry (n = 3). *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

To examine the effects of the exogenous ROS, JFH1 RNA-transfected cells were incubated with 0.25 milliunits/ml of glucose oxidase (GO), which produces H2O2 extracellularly through an enzymatic reaction in the presence of glucose, mimicking ROS generation during inflammation. GO decreased the intracellular JFH1 RNA by 30 ± 8% (p < 0.05) and exacerbated the suppression of HCV RNA by BSO (Fig. 4C). In addition, JFH1 RNA levels decreased with 25, 50, and 100 μm H2O2 (Fig. 4D). Treating cells with BSO plus GO or either agent alone likewise suppressed the subgenomic JFH1 RNA replication (Fig. 4E). BSO and H2O2 also countered the enhancement of HCV replication by ethanol (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and Trolox, a water soluble vitamin E, either increased or had no significant effect on the ethanol-induced enhancement of HCV replication (Fig. 4G). These cell treatments did not induce cytotoxicity, as determined by the ATP assay (data not shown). Thus, ROS were not likely to be responsible for the potentiation of HCV RNA replication by ethanol. These data are consistent with the suppression of HCV RNA replication previously observed with HCV genotype 1 (10, 11).

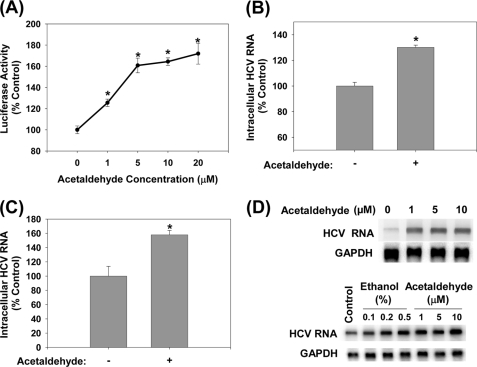

Acetaldehyde Increases the Replication of HCV

We next evaluated whether another major product of ethanol metabolism, acetaldehyde, had similar effects on HCV as ethanol. Acetaldehyde, at physiologically relevant concentrations (25), significantly increased the HCV RNA content in both non-virus producing and virus-producing JFH1 cells (Fig. 5, A and B). Infecting naïve cells with virus-containing medium and then treating with 5 μm acetaldehyde also led to significant increases in HCV replication (Fig. 5C). To examine whether acetaldehyde had similar effects on genotype 1b HCV, SgPC2 cells were also incubated with acetaldehyde and analyzed for changes in HCV replication. Acetaldehyde likewise elevated the HCV RNA level in these cells (Fig. 5D). Another Con1 HCV subgenomic replicon cell clone, Clone B, derived in another laboratory (17), responded similarly to ethanol and acetaldehyde, indicating that the response is not specific to our cell clone (Fig. 5D). Thus, acetaldehyde is sufficient to potentiate HCV replication of both genotypes 1b and 2a.

FIGURE 5.

Acetaldehyde increases intracellular HCV RNA. SgJFH1-Luc (A) and JFH1 RNA-transfected cells (B), Huh7.5 cells inoculated with JFH1 virions (C), SgPC2 and Clone B cells (D) were incubated with acetaldehyde for 24 h and analyzed for HCV RNA by Northern blot or qRT-PCR (n = 3). *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample size (p < 0.05).

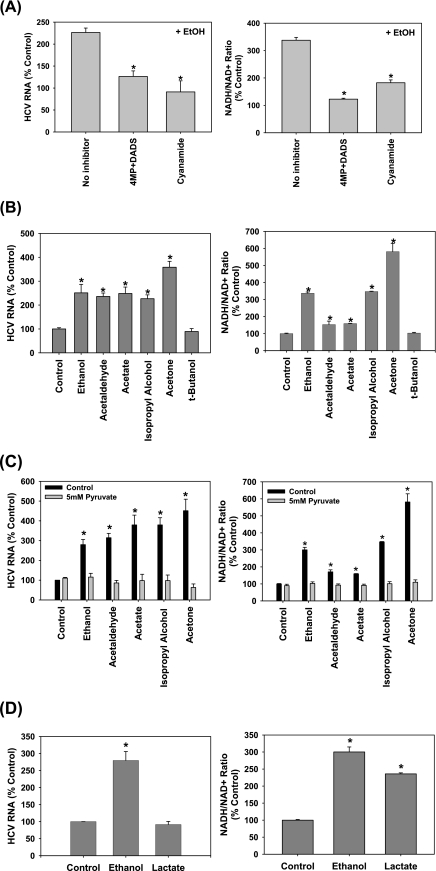

Isopropyl Alcohol and Acetone Also Potentiate HCV Replication, the Role of NADH/NAD+

We continued to investigate whether acetaldehyde itself or products of acetaldehyde metabolism are critical for the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol by inhibiting aldehyde dehydrogenase with cyanamide (see Fig. 3A). Cyanamide suppressed the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol just as inhibiting the first step of ethanol metabolism with 4-methylpyrazole (4MP) and DADS did, suggesting that it is not acetaldehyde itself but a downstream product of acetaldehyde metabolism that increases HCV replication (Fig. 6A, left panel).

FIGURE 6.

Role of NADH/NAD+ in the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetate, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone. SgPC2 cells, supporting Con1 subgenomic HCV RNA replication, were treated with (A) 0.2% ethanol ± 0.1 mm 4MP plus 25 μm DADS or 0.1 mm cyanamide (n = 3); (B) 0.2% ethanol, 5 μm acetaldehyde, 5 μm acetate, 0.2% isopropyl alcohol, 2 mm acetone, or 25 mm tert-butanol (n = 4); (C) 0.2% ethanol, 5 μm acetaldehyde, 5 μm acetate, 0.2% isopropyl alcohol, and 2 mm acetone, with and without 5 mm pyruvate (n = 3); or (D) 0.2% ethanol or 5 mm lactate for 3 h for NADH/NAD+ ratio measurement or 24 h for HCV RNA levels. HCV RNA levels were monitored by Northern blot (A–D, left panels). NADH/NAD+ ratios were measured by an enzymatic NADH recycling assay, as described under “Experimental Procedures” (A–D, right panels). Northern blots were quantified by densitometry. *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

Acetaldehyde metabolism by aldehyde dehydrogenase generates NADH and acetate (Fig. 3A). To determine the potential role of NADH, we first evaluated the effects of isopropyl alcohol. Isopropyl alcohol (0.2%, v/v) increases the levels of NADH like ethanol but generates acetone instead of acetaldehyde. To our surprise, isopropyl alcohol also increased the HCV RNA level (Fig. 6B, left panel) (26). Both isopropyl alcohol and ethanol increased NADH/NAD+ ratio in these cells, as expected (Fig. 6B, right panel). In contrast, tert-butanol did not elevate HCV replication or the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 6B).

Moreover, we found that acetate itself increased the level of HCV RNA as treating cells with acetone also did. In addition, ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetate, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone all showed corresponding increases in NADH/NAD+ ratios (Fig. 6B, right panel) (4, 27). The NADH/NAD+ ratios were positively correlated with HCV RNA content in all of these treatments (r = 0.95, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). The suppression of HCV replication by cyanamide, 4MP, and DADS in Fig. 6A (left panel) was also associated with corresponding decreases in the NADH/NAD+ ratios (Fig. 6A, right panel). Therefore, changes in HCV replication paralleled the changes in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, produced by these treatments.

Then, we examined whether increased NADH/NAD+ ratio was required for the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol and these other agents. Pyruvate, which re-oxidizes cytosolic NADH to NAD+, completely abrogated the increases in HCV replication and NADH levels during ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetate, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone treatments (Fig. 6C). Methylene blue, which also oxidizes NADH, had similar effects on HCV as pyruvate (data not shown). In contrast, lactate, which produces NADH in the cytosol independent of ethanol, increased NADH levels to 235.9 ± 11.9% (p < 0.05) of the control level but had little to no effect on HCV replication (Fig. 6D). Together, these data indicate that whereas an alteration of cellular NADH/NAD+ levels seems necessary for the ethanol-induced increases in HCV replication, elevated NADH/NAD+ may not be sufficient to increase HCV replication.

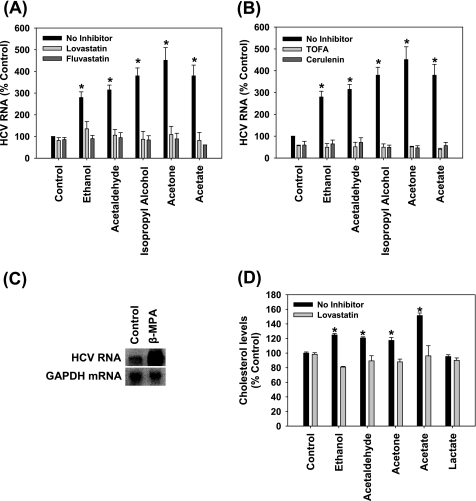

The Potentiation of HCV Replication by Ethanol Requires Lipogenesis

NADH has diverse functions in the cell, and one of these functions includes modulation of lipid metabolism. For example, NADH can inhibit mitochondrial β-oxidation and increase fatty acid synthesis (28). It is well-established that ethanol modulates fatty acid metabolism in part through NADH, and that this plays an important role in the development of steatosis in the alcoholic liver (28). Acetate and acetone would generate acetyl-CoA, which also drives lipogenesis (27, 28). Furthermore, cholesterol metabolism and fatty acid biosynthesis are important in HCV RNA replication (29). Lovastatin and fluvastatin, which are competitive inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase, and 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid (TOFA) and cerulenin, which inhibits fatty acid biosynthesis, have been shown to suppress the basal level of HCV replication (29, 30). Therefore, we next examined whether the potentiation of HCV RNA replication by above agents might be inhibited by modulators of lipid metabolism.

Lovastatin, fluvastatin, TOFA, and cerulenin almost completely inhibited the potentiation of HCV RNA replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate (Fig. 7, A and B). In addition, inhibiting β-oxidation of fatty acids with β-mercaptopropionic acid caused a 15.2 ± 1.7-fold (p < 0.01) increase in HCV replication in these cells (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetone, and acetate treatments increased the total intracellular cholesterol content, which was attenuated by lovastatin (Fig. 7D). Lactate, which increased NADH/NAD+ without increasing HCV replication, had no significant effect on cholesterol levels (Fig. 7D). The data suggest that the elevation of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetone, and acetate is mediated by increases in intracellular cholesterol and can be abrogated by the inhibition of cholesterol or fatty acid biosynthetic pathways.

FIGURE 7.

Role of lipogenesis in the enhancement of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate. SgPC2 cells were treated for 24 h with (A and B) 0.2% ethanol, 5 μm acetaldehyde, 0.2% isopropyl alcohol, 2 mm acetone, 5 μm acetate ± 30 min pretreatment with (A) 5 μm lovastatin, 5 μm fluvastatin, (B) 5 μg/ml TOFA, 5 μg/ml cerulenin, or with (C) 2 mm β-mercaptopropionic acid (β-MPA). Then, HCV RNA levels were monitored by Northern blot and quantified by densitometry (n = 3). D, SgPC2 cells, treated for 24 h with ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetone, and acetate ± lovastatin, were monitored for cholesterol levels (n = 3). Lovastatin was activated, as described, before use (29). *, indicates statistically significant difference for indicated sample sizes (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

High HCV titer is associated with the development and progression of liver diseases (31). In addition, ethanol consumption, high BMI, and high viral titer are strongly associated with poor response to anti-HCV therapy (32). Therefore, the increased HCV replication we saw with physiological levels of ethanol and acetaldehyde is likely to contribute to the pathogenesis and at least partly explain the negative effects that ethanol has on interferon-α therapy. Ethanol has been shown to suppress the antiviral function of interferon-α by interfering with the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (33); however, this is not likely to explain the potentiation of HCV replication we saw with ethanol because HCV effectively suppresses the type I interferon response in Huh7 cells. Additionally, ethanol and acetaldehyde could increase HCV replication in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5 cells (Fig. 5C, also, data not shown) (18, 34). Importantly, some ethanol treatments in this study were performed while wrapping cell culture dishes with parafilm to decrease loss of ethanol due to evaporation. However, we observed similar potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol, with and without the parafilm. The use of the parafilm also did not induce hypoxia as no significant change in the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α could be found (data not shown).

Previously, it has been suggested that some of the key ethanol metabolizing enzymes might not be expressed in Huh7 cells (33). Indeed, we also found that alcohol dehydrogenase I is decreased in our Huh7 cells compared with human liver. However, CYP2E1 activity of our cells were within the normal range for human liver, and CYP2E1 expression could be enhanced by ethanol (Fig. 3). In addition, ethanol and acetaldehyde elevated the NADH/NAD+ ratio, indicating that ethanol is being metabolized by our cells. Also, note that even though our cells do not have all of the normal ethanol metabolizing enzymes, our discovery that acetaldehyde and acetate can enhance HCV replication is significant as they bypass these reactions.

A previous study by Zhang et al. (3) using various chemical inhibitors of ethanol metabolism, suggested that some downstream metabolites of ethanol were involved in the potentiation of subgenomic HCV RNA replication by ethanol. Our data are in agreement with this study and suggest that ethanol and acetaldehyde also directly enhance HCV replication in the context of the complete viral replication cycle. In terms of the mechanism, we found that isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate also increase HCV replication, and increased NADH/NAD+ ratio was required for the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, as well as isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate. In contrast, t-butanol, a tertiary alcohol that is poorly metabolized by humans and does not increase the NADH/NAD+ ratio, did not elevate HCV replication, as predicted by our model (Fig. 6B). The NADH/NAD+ ratio in ethanol-treated cells was decreased by cyanamide (Fig. 6A), suggesting that NADH is generated downstream of acetaldehyde (Fig. 3A). Acetate, the downstream metabolite of acetaldehyde, was previously considered inert but there is evidence that it can be converted to acetyl-CoA and other metabolic intermediates by mammalian cells (24, 28). Isopropyl alcohol is known to be metabolized into acetone and possibly other ketone bodies that can also be converted to acetyl-CoA (27). The mechanism by which isopropyl alcohol increases the NADH/NAD+ ratio in our system is unclear and may involve residual ADH or hitherto uncharacterized enzyme activity that is induced by HCV.

In terms of how NADH increases HCV replication, NADH plays key roles in cellular bioenergetics and can modulate fatty acid synthesis as well as suppress β-oxidation (24, 28). We were interested in the potential involvement of lipids because HCV replicates in cholesterol-rich compartments in the cell, and cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism have been shown to be important for HCV replication (29). Specifically, cholesterol metabolism increases basal HCV replication by the geranylgeranylation of FBL2 (29). We found that inhibiting the host mevalonate pathway with statins and fatty acid synthesis with TOFA or cerulenin blunted the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate, whereas inhibiting β-oxidation dramatically increased HCV replication (Fig. 7). In addition, the potentiation of HCV replication by these agents was accompanied by an increase in the intracellular cholesterol content, which was attenuated by lovastatin (Fig. 7D). Regarding potential effects of NADH on the ATP, overall ATP levels were not significantly perturbed in these cells by ethanol or other treatments (data not shown), suggesting that ATP is not likely to explain the effects that ethanol had on HCV. In fact, ethanol also increased the rate of HCV replication in the in vitro replication assay (Fig. 2C and 2D) which was performed in the presence of excess ATP. Taken together, these data indicate that the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetate, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone ultimately requires host lipid metabolism and is sensitive to lipid modulators, which points to potential targets for therapy. The concentrations of lovastatin and fluvastatin used here are higher than the doses used clinically to treat hypercholesterolemia. However, it is possible that statins, if used in combination with antivirals or other lipid modulators, will help control HCV replication, particularly in chronic alcoholics who show resistance to standard anti-HCV therapy (35). It is also interesting to note that the concentrations of acetone that enhanced HCV replication in this study are physiological levels that can be attained during metabolic dysfunction such as diabetes and during starvation (27), and HCV infection can lead to insulin resistance (36). In addition, acetate, which increased HCV replication at μm to mm concentrations in this study (Fig. 6B and data not shown), is used in hemodialysis.

Interestingly, increasing the NADH/NAD+ ratio with lactate was not sufficient to increase HCV replication, suggesting that other factors may also play a role (Fig. 7D). Lactate also did not increase the intracellular cholesterol level. These results are consistent with an important role of cholesterol in the regulation of HCV replication. The data also indicate that even though ethanol and lactate both increase the NADH/NAD+ ratio, ethanol is more lipogenic than lactate in these cells. The reason for these differences is unclear but it might be explained at least in part by the fact that ethanol can inhibit citric acid cycle as well as gluconeogenesis, which may cause acetate/acetyl-CoA produced by ethanol metabolism to be shunted more toward the lipogenic pathways, whereas these processes are likely to be stimulated by lactate (37). Ethanol can also decrease the total oxidation of fatty acids to CO2, and increase the breakdown of glycogen, which may further drive lipogenesis in these cells (37–39). Further investigation into these effects will be beneficial to understanding how different metabolic conditions would affect HCV replication in hepatocytes.

Recently, McCartney et al. (7) reported an elevation of HCV RNA by ethanol in Huh7 replicon cells, transfected with CYP2E1; the effect could be suppressed by NAC, leading to the conclusion that the increase was due to ROS generation by CYP2E1. In contrast, we have consistently found that ROS suppresses HCV replication whereas antioxidants tend to counter this suppression (10–14) (Fig. 4). In particular, our BSO studies clearly demonstrate that endogenous ROS are sufficient to suppress HCV replication in cell culture (10, 11). Also, NAC and vitamin E either enhanced or had no significant effect on the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol (Fig. 4G) as well as acetaldehyde, isopropyl alcohol, acetone, and acetate (data not shown). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. However, CYP2E1 generates acetaldehyde as well as ROS, both of which can react with thiols, such as cysteine and GSH, which are generated from NAC, and the study by McCartney et al. did not differentiate whether the potentiation of HCV replication by ethanol was due to ROS, acetaldehyde, or other variables (7, 28). NAC can also have other effects on cells, including alteration of the pH and acting as a pro-oxidant, and careful monitoring of the pH and comparison with other antioxidants and pro-oxidants, therefore, are necessary. Indeed, our findings have been recently corroborated by other studies that show that HCV RNA replication is enhanced by antioxidants (e.g. vitamins E and C) and suppressed by lipid peroxidation products and ROS (12–14, 40). The mechanism by which ROS suppresses HCV replication is still not completely clear but it is likely to involve calcium and the dissociation of HCV replication complex from the membranes (10, 11). Detailed understanding of the mechanism by which ROS suppresses HCV replication and how acetaldehyde, NADH, acetyl-CoA, and ROS affect HCV in vivo will require additional in vitro and animal studies.

Therefore, we show that physiological levels of ethanol, acetaldehyde, and acetone promote HCV replication in the context of the complete HCV replication, and that the response is likely mediated by the modulation of host lipid metabolism requiring elevated NADH/NAD+. Further study into the precise mechanisms of this regulation may lead to the development of novel treatments that target both the virus and its pathogenic interactions with ethanol in chronic hepatitis C patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Nandipati and Albert Sun for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Jerome Lasker for CYP2E1 antibodies, Dr. Stanley Lemon for pRL-HL construct, and Dr. Charles Rice/Apath, LLC for Clone B and Huh7.5 cells. We also thank Drs. Arthur Cederbaum and T. S. Benedict Yen for discussion.

This work was supported by start-up funds from the University of California, Merced (to J. C.).

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- nt

- nucleotides

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- IRES

- internal ribosomal entry site

- DADS

- diallyl disulfide

- BSO

- l-buthionine S,R-sulfoximine

- GSH

- glutathione

- GO

- glucose oxidase

- NAC

- N-acetylcysteine

- 4MP

- 4-methylpyrazole

- TOFA

- 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jamal M. M., Morgan T. R. (2003) Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17, 649–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sata M., Fukuizumi K., Uchimura Y., Nakano H., Ishii K., Kumashiro R., Mizokami M., Lau J. Y., Tanikawa K. (1996) J. Viral. Hepat. 3, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang T., Li Y., Lai J. P., Douglas S. D., Metzger D. S., O'Brien C. P., Ho W. Z. (2003) Hepatology 38, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seronello S., Sheikh M. Y., Choi J. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 869–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cromie S. L., Jenkins P. J., Bowden D. S., Dudley F. J. (1996) J. Hepatol. 25, 821–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamai T., Seki T., Shiro T., Nakagawa T., Wakabayashi M., Imamura M., Nishimura A., Yamashiki N., Takasu M., Inoue K., Okamura A. (2000) Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 24, Suppl. 4, 106S–111S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCartney E. M., Semendric L., Helbig K. J., Hinze S., Jones B., Weinman S. A., Beard M. R. (2008) J. Infect. Dis. 198, 1766–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trujillo-Murillo K., Alvarez-Martinez O., Garza-Rodríguez L., Martínez-Rodríguez H., Bosques-Padilla F., Ramos-Jiménez J., Barrera-Saldaña H., Rincón-Sánchez A. R., Rivas-Estilla A. M. (2007) J. Viral Hepat. 14, 608–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moradpour D., Penin F., Rice C. M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi J., Forman H. J., Ou J. H., Lai M. M., Seronello S., Nandipati A. (2006) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41, 1488–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi J., Lee K. J., Zheng Y., Yamaga A. K., Lai M. M., Ou J. H. (2004) Hepatology 39, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang H., Chen Y., Ye J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18666–18670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano M., Ikeda M., Abe K., Dansako H., Ohkoshi S., Aoyagi Y., Kato N. (2007) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 2016–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroki M., Ariumi Y., Ikeda M., Dansako H., Wakita T., Kato N. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 2338–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato T., Date T., Miyamoto M., Sugiyama M., Tanaka Y., Orito E., Ohno T., Sugihara K., Hasegawa I., Fujiwara K., Ito K., Ozasa A., Mizokami M., Wakita T. (2005) J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 5679–5684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakita T., Pietschmann T., Kato T., Date T., Miyamoto M., Zhao Z., Murthy K., Habermann A., Kräusslich H. G., Mizokami M., Bartenschlager R., Liang T. J. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blight K. J., Kolykhalov A. A., Rice C. M. (2000) Science 290, 1972–1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blight K. J., McKeating J. A., Rice C. M. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 13001–13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang T. K., Crespi C. L., Waxman D. J. (1998) Methods Mol. Biol. 107, 147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eysseric H., Gonthier B., Soubeyran A., Bessard G., Saxod R., Barret L. (1997) Alcohol 14, 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin H. R. (2006) Intervirology 49, 18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall D. J., Heisler L. M., Lyamichev V., Murvine C., Olive D. M., Ehrlich G. D., Neri B. P., de Arruda M. (1997) J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 3156–3162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honda M., Kaneko S., Matsushita E., Kobayashi K., Abell G. A., Lemon S. M. (2000) Gastroenterology 118, 152–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cederbaum A. I. (1991) Alcohol Alcohol Suppl 1, 291–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adachi J., Mizoi Y., Fukunaga T., Ogawa Y., Imamichi H. (1989) Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 13, 601–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clemens D. L., Forman A., Jerrells T. R., Sorrell M. F., Tuma D. J. (2002) Hepatology 35, 1196–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalapos M. P. (1999) Med. Hypotheses 53, 236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieber C. S. (2004) Alcohol 34, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye J. (2007) PLoS Pathog 3, e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sagan S. M., Rouleau Y., Leggiadro C., Supekova L., Schultz P. G., Su A. I., Pezacki J. P. (2006) Biochem. Cell Biol. 84, 67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gretch D., Corey L., Wilson J., dela Rosa C., Willson R., Carithers R., Jr., Busch M., Hart J., Sayers M., Han J. (1994) J. Infect. Dis. 169, 1219–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosogaya S., Ozaki Y., Enomoto N., Akahane Y. (2006) Transl. Res. 148, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plumlee C. R., Lazaro C. A., Fausto N., Polyak S. J. (2005) Virol. J. 2, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gale M., Jr., Foy E. M. (2005) Nature 436, 939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bader T., Fazili J., Madhoun M., Aston C., Hughes D., Rizvi S., Seres K., Hasan M. (2008) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 1383–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheikh M. Y., Choi J., Qadri I., Friedman J. E., Sanyal A. J. (2008) Hepatology 47, 2127–2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badawy A. A. (1977) Alcohol Alcohol 12, 120–136 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adiels M., Boren J., Caslake M. J., Stewart P., Soro A., Westerbacka J., Wennberg B., Olofsson S. O., Packard C., Taskinen M. R. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1697–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Towle H. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23235–23238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yano M., Ikeda M., Abe K. I., Kawai Y., Kuroki M., Mori K., Dansako H., Ariumi Y., Ohkoshi S., Aoyagi Y., Kato N. (2009) Hepatology 50, 678–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]