Abstract

We tested the effects of inflammation on renal dopamine D1 receptor signaling cascade, a key pathway that maintains sodium homeostasis and blood pressure during increased salt intake. Inflammation was produced by administering lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 4 mg/kg ip) to rats provided without (normal salt) and with 1% NaCl in drinking water for 2 wk (high salt). Control rats had saline injection and received tap water. We found that LPS increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α in the rats given either normal- or high-salt intake. Also, these rats had higher levels of oxidative stress markers, malondialdehyde and nitrotyrosine, and lower levels of antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase in the renal proximal tubules (RPTs). The nuclear levels of transcription factors NF-κB increased and Nrf2 decreased in the RPTs in response to LPS in rats given normal and high salt. Furthermore, D1 receptor numbers, D1 receptor proteins, and D1 receptor agonist (SKF38393)-mediated 35S-GTPγS binding decreased in the RPTs in these rats. The basal activities of Na-K-ATPase in the RPTs were similar in control and LPS-treated rats given normal and high salt. SKF38393 caused inhibition of Na-K-ATPase activity in the primary cultures of RPTs treated with vehicle but not in the cultures treated with LPS. Furthermore, LPS caused an increase in blood pressure in the rats given high salt but not in the rats given normal salt. These results suggest that LPS differentially regulates NF-κB and Nrf2, produces inflammation, decreases antioxidant enzyme, increases oxidative stress, and causes D1 receptor dysfunction in the RPTs. The LPS-induced dysfunction of renal D1 receptors alters salt handling and causes hypertension in rats during salt overload.

Keywords: oxidative stress, sodium transporter, GPCR, renal proximal tubules

inflammation is linked to a wide variety of pathophysiological processes. Several studies recognize it as a central mechanism contributing to progression of cardiovascular disease (9, 32), hypertension (37, 39), diabetes (15), and myocardial ischemia and infarction (32). These inflammatory states are caused by organ tissue malfunction and homeostasis imbalance of one or several physiological systems. It is assumed that the classic instigators of inflammation “infection and injury” do not play a role in the etiologies of these situations (33).

The transcription factor NF-κB is a ubiquitous protein which plays a critical role in the transcription of cytokine genes, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and in the inflammatory processes (22, 27). Much of our understanding of NF-κB is derived from studying immunologically relevant signaling pathways. Studies implicate NF-κB in gene expression events that impact cell survival, differentiation, and proliferation (22), whereas its dysregulation is linked to various pathological situations.

Nuclear erythroid-related factor 1 and 2 (Nrf1 and Nrf2) belong to bZIP transcription factor family and are ubiquitously expressed. Nrf1 and in particular Nrf2 by trans activating anti-oxidant response element present in the promoter of genes encode enzymes involved in phase II detoxification and anti-oxidant defense (31). These anti-oxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD) protect cellular damage and help maintain cellular homeostasis during oxidative stress.

Renal dopamine is an important regulator of blood pressure, sodium balance, and kidney function (3, 28). Dopamine exerts its effects via activation of D1-like and D2-like receptors, which belong to G protein-coupled receptor family (3, 28, 35). Out of these two receptor subtypes, D1-like receptor signaling cascade is linked to the inhibition of sodium transporters, Na-K-ATPase and Na/H exchanger in renal proximal tubules (RPTs) (3, 23, 25, 28, 35). It is the inhibition of these transporters in RPTs which promotes sodium excretion and contributes to the maintenance of sodium balance and blood pressure particularly during increases in sodium intake (23, 38).

Abnormalities in response to dopamine and in D1 receptor function have been implicated in the increase in blood pressure in hypertensive patients (40), in the elderly (52), and in rodent models of genetic and salt-sensitive hypertension (10, 11, 19, 24, 30, 38, 41). Both D1 receptor dysfunction and the development of hypertension have been linked to the increase in oxidative stress in these situations (2, 8, 47). However, these situations are also associated with inflammation (17, 34, 37, 39, 42). It is not known whether inflammation per se alters renal D1 receptor function. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the role of inflammation on D1 receptor function in RPTs of young Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats. Inflammation in SD rats was produced by administering lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and was confirmed by measuring inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). NF-κB and Nrf2 involved in transcription of genes of inflammation and anti-oxidant enzyme, respectively, were also measured in the RPTs. Given the importance of renal D1 receptors in maintaining sodium homeostasis and blood pressure during increased salt intake, we measured blood pressure and markers of D1 receptor function in response to LPS in rats on normal- and high-salt intake. Furthermore, markers of oxidative stress, malondialdehyde (MDA) and protein nitrotyrosine, were also measured in the RPTs.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animals.

Male SD rats (225–250 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and allowed to acclimate for at least 5 days before any studies were conducted. They were fed commercial rat chow and water ad libitum (unless specified) and housed in a temperature-, humidity-, and light-controlled (12:12-h light-dark cycle) environment in the University of Houston Animal Care Facility. The animals were used in the study with the approval of the Institution's Animal Care and Use Committee and according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Animal treatment.

The rats were randomly grouped as control, LPS, and high salt-LPS (HS-LPS) groups. The control and LPS rat groups were given tap water to drink, whereas HS-LPS rat group had 1% sodium chloride in drinking water for 2 wk. One day before death, the LPS and HS-LPS rat groups were administered with LPS (4 mg LPS in saline/kg body wt ip). The control rat group received only saline injection.

Blood pressure measurement.

As described previously (8), rats were anesthetized with Inactin (100 mg/kg ip). Tracheotomy was performed to facilitate breathing. To measure blood pressure and to collect blood samples, the left carotid artery was catheterized with PE-50 tubing. This tubing was connected to a pressure transducer, which was connected to an amplifier (GRASS, LP122). Blood pressure was continuously recorded for 30 min using GRASS PolyView Data Acquisition and Analysis Software systems (Astro-Med, GRASS Instrument Division, West Warwick, RI). After blood pressure measurement, aliquots of blood samples were withdrawn and plasma was isolated by centrifugation and kept frozen until further use.

RPT preparations.

As previously described (4), an in situ enzyme digestion procedure was used to prepare RPTs. Briefly, a midline abdominal incision was made, aorta was catheterized with PE-50 tubing, and kidneys were perfused with collagenase and hyaluronidase. The kidneys were removed and kept in ice-cold oxygenated Krebs buffer containing (in mM) 1.5 CaCl2, 110 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, and 2 HEPES (pH 7.6). Coronal sections of the kidneys were obtained, and superficial cortical tissue slices (rich in proximal tubules) were dissected out with a razor blade. The cortical slices were kept in fresh Krebs buffer. Enrichment of proximal tubules was carried out using 20% Ficoll in Krebs buffer. The band at Ficoll interface was collected and washed in Krebs buffer by centrifugation at 250 g for 5 min. Tubular cells' viability was performed using the Trypan blue exclusion test.

Primary cultures from RPTs.

The tubules isolated from the kidneys of control SD rats, as mentioned above, were washed with DMEM/F12 (1:1) culture media by centrifugation. The tubular pellet was used to culture epithelial cells as we described earlier (5) to study direct effect of LPS on Na-K-ATPase activity.

Preparation of proximal tubular membranes.

RPTs were homogenized in sucrose buffer (in mM: 250 sucrose, 10 Tris, 1 PMSF, pH 7.4), and membranes were prepared using differential centrifugation method (4, 5).

D1 receptor numbers and D1 receptor proteins.

To determine the number of D1 receptors on the membranes, binding of a D1 receptor antagonist 3H-SCH-23390 to membranes was performed as described previously (4, 5). Briefly, for saturation binding, 50 μg of membrane proteins were incubated with 20 nM 3H-SCH23390 in a final volume of 250 μl binding buffer at 25°C for 90 min. Unlabeled SCH23390 (10 μM) was used for determining nonspecific bindings. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between the total and nonspecific bindings. D1 receptor protein was determined by Western blotting as described earlier (4, 5).

35S-GTPγS binding assay.

As previously described (4, 5), membrane proteins (5 μg) in the presence of 35S-GTPγS (0.6 nM corresponding to ∼100,000 cpm) and GDP (10 μM) were incubated with various concentrations of SKF38393 (10−10-10−7 mol/l) in a final volume of 100 μl for 1 h at 30°C. Nonspecific binding was determined by adding 100 μM unlabeled GTP to the assay media. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and nonspecific bindings.

ELISA.

TNF-α and IL-6 in the plasma and RPT homogenates were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Na-K-ATPase assay.

Na-K-ATPase activity in the RPTs was measured by determining phosphate released from ATP in the absence and presence of Na-K-ATPase inhibitor ouabain using a colorimetric method (33). 86Rubidium (86Rb) uptake, an index of Na-K-ATPase activity, in primary cultures of RPTs was carried out according to our published method (5). Briefly, cells were incubated without or with SKF38393 (10−6 M) followed by addition of 86Rb+ (3 μCi/ml). The cells were lysed with 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and radioactivity was measured directly in cell lysate using a gamma counter. Na-K-ATPase activity was determined as the difference between 86Rb+ uptake in the absence and presence of ouabain (1 mM).

Nuclear protein extraction.

Nuclear proteins from RPTs were extracted using an extraction kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as described earlier (31). Transcription factors NF-κB and Nrf2 were determined in the nuclear proteins by Western blotting using specific primary rabbit NF-κB-p65 (34) and Nrf2 (4) antibodies. Nuclear histone-4 protein was probed using histone-4 antibody (Millipore, Temecula, CA) as a control for protein loading.

Measurement of MDA and nitrotyrosine.

The levels of MDA and nitrotyrosine in the RPT homogenates were determined by colorimetric (4) and Western blotting (7) methods, respectively. Both MDA and nitrotyrosine are markers of oxidative stress. The levels of nitrotyrosine are measured by Western blotting, which help detect oxidative damage in different proteins in the same sample.

Measurement of SOD.

SOD in the RPT homogenates was measured by Western blotting following our published method (4).

Protein measurement.

Proteins were measured using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) and BSA as standards.

Statistics.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by ANOVA or t-test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test wherever applicable. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

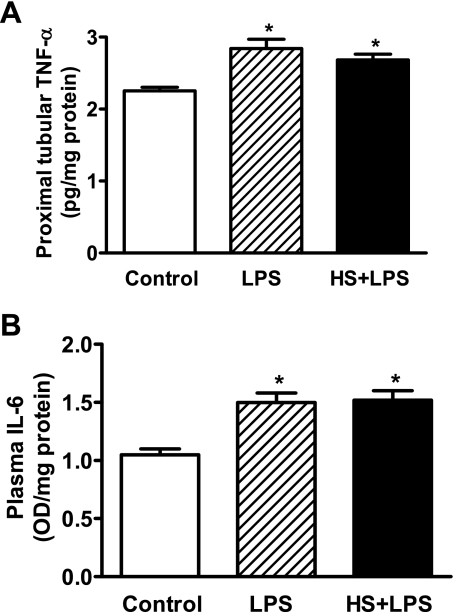

As shown in Fig. 1, the levels of markers of inflammation TNF-α and IL-6 increased in LPS-treated compared with control rats. These markers also increased in response to LPS in rats with high-salt intake.

Fig. 1.

LPS increases inflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-6 in rats given normal (LPS) and high salt (HS+LPS). TNF-α (A) in the renal proximal tubules (RPTs) and IL-6 (B) in the plasma were measured by ELISA. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from control rats.

The levels of markers of oxidative stress, MDA (Fig. 2A), and protein nitrotyrosine (Fig. 2B) in the RPTs increased in LPS-treated compared with control rats. LPS also increased the levels of these markers in the RPTs of rats given high salt. The levels of antioxidant enzyme SOD decreased in the RPTs in response to LPS in rats given normal and high salt (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

LPS increases oxidative and nitrative stress markers and decreases anti-oxidant superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme in RPTs of rats. A: malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in rats given normal (LPS) and high salt (HS+LPS). B, left: representative immunoblot of protein nitrotyrosine; right: quantification of protein nitrotyrosine bands A, B, and C in control (lane 1) and LPS-treated rats given normal (lane 2) and high salt (lane 3). C, top: representative immunoblot of SOD and GAPDH; bottom: bars are ratios between the densities of SOD and GAPDH. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from control. #Significantly different from LPS in A and control band B in B. $Significantly different from control band C in C.

The nuclear levels of transcription factor NF-κB involved in inflammatory processes increased (Fig. 3A), whereas transcription factor Nrf2 responsible for antioxidant defenses decreased (Fig. 3B) in the RPTs of LPS-treated rats given either normal or high salt.

Fig. 3.

Nuclear levels of NF-κB increase and of Nrf2 decrease in RPTs in response to LPS. A, top: representative immunoblot of NF-κB and protein loading control histone-4 in control (lane 1) and LPS-treated rats given normal (lane 2) and high salt (lane 3). Bottom: bars represent the ratios of the densities of NF-κB and histone-4. B, top: representative immunoblot of Nrf2 and protein loading control histone-4 in control (lane 1) and LPS-treated rats given normal (lane 2) and high salt (lane 3). Bottom: bars represent the ratios between the densities of Nrf2 and histone-4. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from control. #Significantly different from LPS.

The D1 receptor numbers (Fig. 4A) and D1 receptor proteins (Fig. 4B) decreased in the RPT membranes of LPS-treated rats irrespective of salt intake compared with control rats. The levels of D1 receptor proteins were not changed in the RPT homogenates among the three groups (Fig. 4C). The D1 receptor agonist SKF38393 (10−10-10−6 M) increased the binding of 35S-GTPγS in the RPT membranes of control rats; however, it failed to increase the 35S-GTPγS binding in the membranes of LPS-treated rats given normal or high salt (Fig. 5A). The basal activity of Na-K-ATPase in the RPTs was similar in control and LPS-treated rats irrespective of salt intake (control vs. LPS vs. HS-LPS: 105 ± 10 vs. 108 ± 13 vs. 97 ± 17 nmol·mg protein−1·min−1). Moreover, SKF38393 (10−6 M) decreased 86Rb uptake in vehicle-treated epithelial cells, which was attenuated in cells pretreated with LPS (1 μg/ml, overnight; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

LPS decreases D1 receptor numbers and the levels of D1 receptor proteins in the membranes of RPTs. A: radio D1 receptor antagonist 3H-SCH23390 binding in the membranes of RPTs. B, top: representative immunoblot of D1 receptor proteins in the membranes of RPTs from control (lane 1) and LPS-treated rats given normal (lane 2) and high salt (lane 3). Bottom: bars represent the densities of D1 receptor protein. C, top: representative immunoblot blot of D1 receptors and protein loading control GAPDH in the homogenates of RPTs from control (lane 1) and LPS-treated rats given normal (lane 2) and high salt (lane 3). Bottom: bars represent the ratios of the densities of D1 receptors and GAPDH. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from control. #Significantly different from LPS.

Fig. 5.

LPS decreases D1 receptor agonist-mediated receptor G protein coupling and attenuates inhibitory response of the agonist on Na-K-ATPase. A: 35S-GTPγS binding in response to D1 receptor agonist SKF38393 (10−6 M), an index of D1 receptor G protein coupling, in RPT membranes of control (open bars) and LPS-treated rats given normal (hatched bars) and high salt (filled bars). B: 86Rubidium uptake, an index of Na-K-ATPase activity, in primary cultures of RPTs treated with (hatched bars) and without (open bars) LPS (1 μg/ml, overnight). The ability of D1 receptor agonist (1 μM, 10 min) to inhibit Na-K-ATPase activity in cultures treated with vehicle (open bars) attenuates in cultures prior treated with LPS (hatched bars). Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from vehicle in controls in A and B.

As shown in Fig. 6, the systolic but not the diastolic blood pressure increased in response to LPS in rats with high-salt intake.

Fig. 6.

LPS increases systolic but not diastolic blood pressure (BP) in LPS-treated rats on high-salt diet. Rats given high salt are identified by filled bars. Rats given normal salt are identified by open and hatched bars. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 experiments (n = 4–5 animals). *Significantly different from control (open bars). #Significantly different from LPS-treated rats given normal salt (hatched bars).

DISCUSSION

The present study clearly demonstrates that LPS produced inflammation (IL-6 and TNF-α) in SD rats and decreased the levels of Nrf2, a transcription factor involved in anti-oxidant enzyme gene expression, in the nucleus of RPTs. The abundance of an anti-oxidant enzyme SOD decreased while oxidative stress markers, MDA and nitrotyrosine, increased in the RPTs in response to LPS. The D1 receptor function reduced in the RPTs and in renal epithelial cells when LPS was administered in the animal or provided exogenously in the culture media, respectively. In response to LPS, systolic but not diastolic blood pressure increased in the rats with only high-salt intake. These results suggest that inflammation causes dysfunction of renal D1 receptors and is associated with high blood pressure in rats during salt overload.

Inflammation is generally characterized as an increase in the levels of systemic and organ tissue chemokines, cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), and adhesive molecules (e.g., ICAM) (48). It increases in obesity, insulin resistance, essential hypertension, and aging (13, 37, 49). The dysfunction of renal D1 receptors in these situations contributes to increase in blood pressure (30, 38, 40, 51, 52). Therefore, there seems to be a strong association between inflammation and renal D1 receptor dysfunction. To study the effect of inflammation on D1 receptor function, we administered LPS, a bacterial membrane component, to SD rats. This is a commonly used model of inflammation, which has been helpful in understanding the mechanism of progression of renal diseases (40, 41). Higher doses (10 mg/kg) of LPS are reported to produce hypotension (46). In the present study, however, 4 mg/kg LPS administered by intraperitoneal injection did not alter blood pressure in the rats. Nevertheless, the LPS dose used in this study when given intravenously is reported to cause hypotension (14). The discrepancy in the blood pressure between our and the above study may be due to the route LPS is administered (ip vs. iv).

LPS produces inflammation via NF-κB-mediated transcriptional regulation of chemokine and cytokine genes (27). We also found increased nuclear levels of NF-κB, an index of its activation, in the RPTs in response to LPS to a greater extent in rats given high salt than in rats given normal salt. While the reason for higher NF-κB activation in rats given high salt is not known, LPS increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in both groups of rats given normal and high salt. It should be mentioned that TNF-α detected in the RPTs in the present study is not from immune cells but from renal epithelial cells. This notion is based on the fact that 1) while isolating RPTs, immune cells are removed by perfusing the kidney and 2) renal epithelial cells are reported to produce cytokines in cultures (21).

There are studies suggesting interrelationship between inflammation and oxidative stress (45). LPS has been shown to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory marker IL-1β and to decrease Cu/Zn SOD, and to cause renal dysfunction (50). We have also seen an increase in the levels of markers of oxidative stress in RPTs in response to LPS. In addition, in the present study, reduction in antioxidant enzyme Cu/Zn SOD levels and inhibition of the enzyme's transcription factor Nrf2 were also found in RPTs. Nrf2 transcribes a battery of anti-oxidant enzyme genes including Cu/Zn SOD (12). While the study by Yang et al. (50) fails to provide a reason for the reduced Cu/Zn SOD levels, our study suggests that inactivation of Nrf2 during inflammation may have resulted in reduced Cu/Zn SOD levels in RPTs. This may have caused an imbalance in anti-oxidant capacity of RPTs leading to an increase in oxidative stress. Perhaps this is true since an exaggerated production of ROS in response to LPS was reported in peritoneal leukocytes isolated from Nrf2-deficient mice (43). Therefore, it seems that inflammation-induced downregulation of Nrf2 causes disturbances in the cellular anti-oxidant capacity, which may be a universal mechanism for inflammation-induced oxidative stress.

There are compelling pieces of evidence linking renal D1 receptor dysfunction and increase in blood pressure in obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension (30, 38, 44). The direct evidence for D1 receptor in blood pressure regulation comes from the study where mice lacking D1 receptor gene had higher blood pressure (1). It is reported that the inability of dopamine to inhibit sodium transporter Na-K-ATPase is due to uncoupling of D1 receptors from G proteins, which may result in sodium retention and subsequently in an increase in blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive and obese Zucker rats (26, 30). At the same time, these rat models are also associated with inflammation (39), which may be contributing to dysfunction of renal D1 receptors. The present study was an attempt to study the role of inflammation on D1 receptor function during normal and salt overload in SD rats. The purpose to include a salt overload rat group was to find changes in the blood pressure phenotype in them, if any, due to LPS-induced dysfunction of D1 receptors. In the present study, we did not include a rat group given only high salt. This was decided based on our previous findings that normal rats when given only high salt resemble vehicle-treated rats in terms of D1 receptor function and exhibit normal blood pressure (8).

It is interesting to note that LPS causes greater degree of oxidative stress, determined as MDA and nitrotyrosine, in RPTs of rats given high salt. This may be due to a cumulative effect of LPS and salt overload on oxidative stress as salt overload also is reported to increase oxidative stress (16). Probably, this is the reason for a profound decline in D1 receptor G protein coupling and in D1 receptor numbers in response to LPS in rats given high salt. However, a parallel change between D1 receptor numbers and D1 receptor proteins in the membranes in response to LPS in rats given high salt was not seen. This may be due to limitation in the sensitivity of the antibody-based (Western blotting) compared with the radioactive based (radioligand binding) methods. Radioligand binding assays are more sensitive than Western blotting.

Salt overload in normal SD rats is reported to decrease the basal activity of Na-K-ATPase in RPTs (8). However, in the present studies, high salt-induced reduction in Na-K-ATPase activity was not seen in LPS-treated rats. Moreover, D1 receptor agonist SKF38393 failed to inhibit Na-K-ATPase activity in renal epithelial cells in cultures prior treated with LPS. Taken together, these studies suggest an inability of D1 receptors to inhibit Na-K-ATPase and cause sodium excretion during inflammation and may have contributed to an increase in blood pressure in rats with high-salt intake. It should be noted that the effect of inflammation on blood pressure was studied after 24 h of LPS administration. We expect an even higher increase in blood pressure in high salt-fed rats with long-term LPS administration via osmotic pump, which needs to be determined.

We conclude that LPS induces inflammation, increases oxidative stress, and causes D1 receptor G protein uncoupling in RPTs. The LPS-induced dysfunction of renal D1 receptor may be associated with high blood pressure phenotype during salt overload. Furthermore, the increase in oxidative stress during inflammation may be due to downregulation of anti-oxidant capacity in RPTs.

GRANTS

We are thankful to the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (Grants AG-25056 to M. F. Lokhandwala and AG-029904 to M. Asghar) for financial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht FE, Drago J, Felder RA, Printz MP, Eisner GM, Robillard JE, Sibley DR, Westphal HJ, Jose PA. Role of the D1A dopamine receptor in the pathogenesis of genetic hypertension. J Clin Invest 97: 2283–2288, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7915–7922, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aperia AC. Intrarenal dopamine: a key signal in the interactive regulation of sodium metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol 62: 621–647, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asghar M, George L, Lokhandwala MF. Exercise decreases oxidative stress and inflammation and restores renal dopamine D1 receptor function in old rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F914–F919, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asghar M, Chillar A, Lokhandwala MF. Renal proximal tubules from old F344 rats grow into epithelial cells in primary cultures and exhibit increased oxidative stress and reduced D1 receptor function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1326–C1331, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asghar M, Kansra V, Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Hyperphosphorylation of Na pump contributes to defective renal dopamine response in old rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 226–232, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asghar M, Monjok E, Kouamou G, Ohia S, Bagchi D, Lokhandwala M. Super CitriMax (HCA-SX) attenuates increases in oxidative stress, inflammation, insulin resistance and body weight in developing obese Zucker rats. Mol Cell Biol 304: 93–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banday AA, Lau YS, Lokhandwala MF. Oxidative stress causes renal dopamine D1 receptor dysfunction and salt-sensitive hypertension in Sprague-Dawley rats. Hypertension 51: 367–375, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blake GJ, Ridker PM. Novel clinical markers of vascular wall inflammation. Circ Res 89: 763–771, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CJ, Vyas SJ, Eichberg J, Lokhandwala MF. Diminished phospholipase C activation by dopamine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 19: 102–108, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C, Beach RE, Lokhandwala MF. Dopamine fails to inhibit renal tubular sodium pump in hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 364–372, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen XL, Kunsch C. Induction of cytoprotective genes through Nrf2/antioxidant response element pathway: a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr Pharm Des 10: 879–891, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung HY, Kim HJ, Kim KW, Choi JS, Yu BP. Molecular inflammation hypothesis of aging based on the anti-aging mechanism of calorie restriction. Microsc Res Tech 59: 264–272, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, Esposito E, Macarthur H, Matuschak GM, Salvemini D. A role for nitric oxide-mediated peroxynitrite formation in a model of endotoxin-induced shock. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319: 73–81, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dandona P. The link between insulin resistance syndrome and inflammatory markers. Endocr Pract 9, Suppl 2: 53–57, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrian AD, Schriver SD, Lynch T, Prewitt RL. Effect of salt on hypertension and oxidative stress in a rat model of diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F619–F628, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorffel Y, Latsch C, Stuhlmuller B, Schreiber S, Scholze S, Burmester GR, Scholze J. Preactivated peripheral blood monocytes in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 34: 113–117, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fardoun RZ, Asghar M, Lokhandwala M. Role of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB) in oxidative stress-induced defective dopamine D1 receptor signaling in the renal proximal tubules of Sprague-Dawley rats. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 756–764, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gesek FA, Schoolwerth AC. Hormone responses of proximal Na+-H+ exchanger in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F526–F536, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, Rhodes GJ, Berg DT, Gerlitz B, Molitoris BA, Grinnell BW. Activated protein C ameliorates LPS-induced acute kidney injury and downregulates renal iNOS and angiotensin 2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F245–F254, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haij S, Woltman AM, Bakker AC, Daha MR, Kooten C. Production of inflammatory mediators by renal epithelial cells is insensitive to glucocorticoids. Br J Pharmacol 137: 197–204, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NFκB signaling. Cell 132: 344–362, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegde SS, Jadhav AL, Lokhandwala MF. Role of kidney dopamine in the natriuretic response to volume expansion in rats. Hypertension 13: 828–834, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiuchi A, Albrecht FE, Eisner GM, Jose PA, Felder RA. Renal dopamine receptors and pre- and post-cAMP-mediated Na+ transport defect in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F1105–F1111, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Renal dopamine receptor function in hypertension. Hypertension 32: 187–197, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain T, Beheray SA, Lokhandwala MF. Defective dopamine receptor function in proximal tubules of obese Zucker rats. Hypertension 34: 1091–1096, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin W, Zhu L, Guan Q, Chen G, Wang QF, Yin HX, Hang CH, Shi JX, Wang HD. Infuence of Nrf2 genotype on pulmonary NFκB activity and inflammatory response after traumatic brain injury. Ann Clin Lab Sci 38: 221–227, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jose PA, Eisner GM, Felder RA. Renal dopamine receptors in health and hypertension. Pharmacol Ther 80: 149–182, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature 441: 431–436, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinoshita S, Sidhu A, Felder RA. Defective dopamine-1 receptor adenylate cyclase coupling in the proximal convoluted tubule from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Clin Invest 84: 1849–1856, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW. Chemoprevention through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway by phase 2 enzyme inducers. Mutat Res 555: 133–148, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libby P. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 104: 365–372, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454: 428–435, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills PJ, Farag NH, Hong S, Kennedy BP, Berry CC, Ziegler MG. Immune cell CD62L and CD11a expression in response to a psychological stressor in human hypertension. Brain Behav Immun 17: 260–267, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev 78: 189–225, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura A, Niimi R, Yanagawa Y. Renal β2-adrenoceptor modulates the lipopolysaccharide transport system in sepsis-induced acute renal failure. Inflammation 32: 12–19, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F447–F454, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishi A, Eklof AC, Bertorello AM, Aperia A. Dopamine regulation of renal Na+,K+-ATPase activity is lacking in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 21: 767–771, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Ferrebuz A, Parra G, Vaziri ND. Evolution of renal interstitial inflammation and NF-kappaB activation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Nephrol 24: 587–594, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanada H, Jose PA, Hazen-Martin D, Yu PY, Xu J, Bruns DE, Phipps J, Carey RM, Felder RA. Dopamine-1 receptor coupling defect in renal proximal tubule cells in hypertension. Hypertension 33: 1036–1042, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sidhu A, Vachvanichsanong P, Jose PA, Felder RA. Persistent defective coupling of dopamine-1 receptors to G proteins after solubilization from kidney proximal tubules of hypertensive rats. J Clin Invest 89: 789–793, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suematsu M, Suzuki H, Delano FA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. The inflammatory aspect of the microcirculation in hypertension: oxidative stress, leukocytes/endothelial interaction, apoptosis. Microcirculation 9: 259–276, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thimmulappa RK, Scollick C, Traore K, Yates M, Trush MA, Liby KT, Sporn MB, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Biswal S. Nrf2-dependent protection from LPS induced inflammatory response and mortality by CDDO-Imidazolide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 351: 883–889, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trivedi M, Marwaha A, Lokhandwala M. Rosiglitazone restores G protein coupling, recruitment, and function of renal dopamine D1A receptor in obese Zucker rats. Hypertension 43: 376–382, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaziri ND, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mechanism of disease: oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nature Clin Prac 2: 582–593, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Novotný M, Quaiserová-Mocko V, Swain GM, Wang DH. TRPV1-mediated protection against endotoxin-induced hypotension and mortality in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1517–R1523, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White BH, Sidhu A. Increased oxidative stress in renal proximal tubules of the spontaneously hypertensive rat: a mechanism for defective dopamine D1A receptor/G protein coupling. J Hypertens 16: 1659–1665, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White M. Mediators of inflammation and the inflammatory process. J Allergy Clin Immunol 103: S378–S381, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112: 1821–1830, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang CC, Ma MC, Chien CT, Sun WK, Chen CF. Hypoxic preconditioning attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress in rat kidneys. J Physiol 582: 407–419, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu P, Asico LD, Eisner GM, Hopfer U, Felder RA, Jose PA. Renal protein phosphatase 2A activity and spontaneous hypertension in rats. Hypertension 36: 1053–1058, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zemel MB, Sowers JR. Salt sensitivity and systemic hypertension in the elderly. Am J Cardiol 61: 7H–12H, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]