Abstract

Auxin is a phytohormone essential for plant development. Due to the high redundancy in auxin biosynthesis, the role of auxin biosynthesis in embryogenesis and seedling development, vascular and flower development, shade avoidance and ethylene response were revealed only recently. We previously reported that a vitamin B6 biosynthesis mutant pdx1 exhibits a short-root phenotype with reduced meristematic zone and short mature cells. By reciprocal grafting, we now have found that the pdx1 short root is caused by a root locally generated signal. The mutant root tips are defective in callus induction and have reduced DR5::GUS activity, but maintain relatively normal auxin response. Genetic analysis indicates that pdx1 mutant could suppress the root hair and root growth phenotypes of the auxin overproduction mutant yucca on medium supplemented with tryptophan (Trp), suggesting that the conversion from Trp to auxin is impaired in pdx1 roots. Here we present data showing that pdx1 mutant is more tolerant to 5-methyl anthranilate, an analogue of the Trp biosynthetic intermediate anthranilate, demonstrating that pdx1 is also defective in the conversion from anthranilate to auxin precursor tryptophan. Our data suggest that locally synthesized auxin may play an important role in the postembryonic root growth.

Key words: auxin synthesis, root, PLP, PDX1

The plant hormone auxin modulates many aspects of growth and development including cell division and cell expansion, leaf initiation, root development, embryo and fruit development, pattern formation, tropism, apical dominance and vascular tissue differentiation.1–3 Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is the major naturally occurring auxin. IAA can be synthesized in cotyledons, leaves and roots, with young developing leaves having the highest capacity.4,5

Auxin most often acts in tissues or cells remote from its synthetic sites, and thus depends on non-polar phloem transport as well as a highly regulated intercellular polar transport system for its distribution.2

The importance of local auxin biosynthesis in plant growth and development has been masked by observations that impaired long-distance auxin transport can result in severe growth or developmental defects.3,6 Furthermore, a few mutants with reduced free IAA contents display phenotypes similar to those caused by impaired long-distance auxin transport. These phenotypes include defective vascular tissues and flower development, short primary roots and reduced apical dominance, or impaired shade avoidance and ethylene response.7–15 Since these phenotypes most often could not be rescued by exogenous auxin application, it is difficult to attribute such defects to altered local auxin biosynthesis. By complementing double, triple or quadruple mutants of four Arabidopsis shoot-abundant auxin biosynthesis YUCCA genes with specific YUCCA promoters driven bacterial auxin biosynthesis iaaM gene, Cheng et al. provided unambiguous evidence that auxin biosynthesis is indispensable for embryo, flower and vascular tissue development.8,13 Importantly, it is clear that auxin synthesized by YUCCAs is not functionally interchangeable among different organs, supporting the notion that auxin synthesized by YUCCAs mainly functions locally or in a short range.6,8,13

The central role of auxin in root meristem patterning and maintenance is well documented,1,2,16 but the source of such IAA is still unclear. When 14C-labeled IAA was applied to the five-day-old pea apical bud, the radioactivity could be detected in lateral root primordia but not the apical region of primary roots.17 Moreover, removal of the shoot only slightly affected elongation of the primary root, and localized application of auxin polar transport inhibitor naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) at the primary root tip exerted more profound inhibitory effect on root elongation than at any other site.18 These results suggest that auxin generated near the root tip may play a more important role in primary root growth than that transported from the shoot. In line with this notion, Arabidopsis roots have been shown to harbor multiple auxin biosynthesis sites including root tips and the region upward from the tip.4

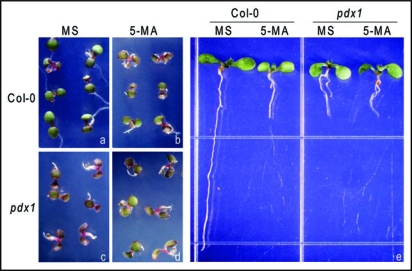

Many steps of tryptophan synthesis and its conversion to auxin involve transamination reactions, which require the vitamin B6 pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor. We previously reported that the Arabidopsis mutant pdx1 that is defective in vitamin B6 biosynthesis displays dramatically reduced primary root growth with smaller meristematic zone and shorter mature cortical cells.19 In the current investigation, we found that the root tips of pdx1 have reduced cell division capability and reduced DR5::GUS activity, although the induction of this reporter gene by exogenous auxin was not changed. Reciprocal grafting indicates that the short-root phenotype of pdx1 is caused by a root local rather than shoot generated factor(s). Importantly, pdx1 suppresses yucca mutant, an auxin overproducer, in root hair proliferation although it fails to suppress the hypocotyl elongation phenotype.20 Our work thus demonstrated that pdx1 has impaired root local auxin biosynthesis from tryptophan. To test whether the synthesis of tryptophan is also affected in pdx1 mutant, we planted pdx1 together with wild-type seeds on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 5-mehtyl-anthranilate (5-MA), an analogue of the Trp biosynthetic intermediate anthranilate.21 Although pdx1 seedlings grew poorly under the control conditions, the growth of wild-type seedlings was more inhibited than that of the pdx1 seedlings on 10 µM 5-MA media (Fig. 1A–D). Compared with the elongated primary root on MS, wild-type seedlings showed very limited root growth on 5-MA (Fig. 1E). The relatively increased tolerance to 5-MA of pdx1 thus indicates that the pdx1 mutant may be defective in Trp biosynthesis, although amino acid analysis of the bulked seedlings did not find clear changes in Trp levels in the mutants (our unpublished data).

Figure 1.

The pdx1 mutant seedlings are relatively less sensitive to toxic 5-methyl anthranilate (5-MA). (A and C) Five-day-old seedlings of the wild type (Col-0) (A) or pdx1 (C) on MS medium. (B and D) Five-day-old seedlings of the wild type (B) or pdx1 (D) on MS medium supplemented with 10 µM 5-MA. (E) Eight-day-old seedlings of the wild type or pdx1 on MS medium without or with 10 µM 5-MA supplement. Sterilized seeds were planted directly on the indicated medium and after two days of cold treatment, the plates were incubated under continuous light at 22–24°C before taking pictures.

We reported that PDX1 is required for tolerance to oxidative stresses in Arabidopsis.19 Interestingly, redox homeostasis appears to play a critical role in Arabidopsis root development. The glutathione-deficient mutant root meristemless1 (rml1) and the vitamin C-deficient mutant vitamin C1 (vtc1) both have similar stunted roots.22,23 Nonetheless, pdx1 is not rescued by either glutathione or vitamin C19 suggesting that the pdx1 short-root phenotype may not be resulted from a general reduction of antioxidative capacity. Interestingly, ascorbate oxidase is found to be highly expressed in the maize root quiescent center.24 This enzyme can oxidatively decarboxylate auxin in vitro, suggesting that the quiescent center may be a site for metabolizing auxin to control its homeostasis.25 It is therefore likely that the reduced auxin level in pdx1 root tips could be partially caused by increased auxin catabolism resulted from reduced vitamin B6 level. We thus conducted experiments to test this possibility. A quiescent center-specific promoter WOX5 driven bacterial auxin biosynthetic gene iaaH26 was introduced into pdx1 mutant. The transgenic seeds were planted on media supplemented with different concentrations of indoleacetamide (IAM), the substrate of iaaH protein. Although promotion of lateral root growth was observed at higher IAM concentrations, which indicates increased tryptophan-independent auxin production from the transgene, no change in root elongation was observed between pdx1 with or without the WOX5::iaaH transgene at any concentration of IAM tested (data not shown), suggesting that the pdx1 short-root phenotype may not be due to increased auxin catabolism.

Taken together, in addition to auxin transport; temporally, spatially or developmentally coordinated local auxin biosynthesis defines the plant growth and its response to environmental changes.8,14,15

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Ben Scheres for kindly providing us with WOX5::iaaH seeds.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/9177

References

- 1.Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: regulation, action and interaction. Ann Bot. 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teale WD, Paponov IA, Palme K. Auxin in action: signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:847–859. doi: 10.1038/nrm2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler JW. Local auxin production: a small contribution to a big field. Bioessays. 2009;31:60–70. doi: 10.1002/bies.080146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ljung K, Hull AK, Celenza J, Yamada M, Estelle M, Normanly J, Sandberg G. Sites and regulation of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1090–1104. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljung K, Hull AK, Kowalczyk M, Marchant A, Celenza J, Cohen JD, Sandberg G. Biosynthesis, conjugation, catabolism and homeostasis of indole-3-acetic acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49:249–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y. The role of local biosynthesis of auxin and cytokinin in plant development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2008;11:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takase T, Nakazawa M, Ishikawa A, Kawashima M, Ichikawa T, Takahashi N, et al. ydk1--D, an auxin-responsive GH3 mutant that is involved in hypocotyl and root elongation. Plant J. 2004;37:471–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobena-Santamaria R, Bliek M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Mol JN, Souer E, Koes R. FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev. 2002;16:753–763. doi: 10.1101/gad.219502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR, Goss KA, Alonso J, Ecker JR, et al. Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3100–3112. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symons GM, Ross JJ, Murfet IC. The bushy pea mutant is IAA-deficient. Physiol Plant. 2002;116:389–397. [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeClere S, Rampey RA, Bartel B. IAR4, a gene required for auxin conjugate sensitivity in Arabidopsis, encodes a pyruvate dehydrogenase E1α homolog. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:989–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2430–2439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepanova AN, Robertson-Hoyt J, Yun J, Benavente LM, Xie D-Y, Dolezal K, et al. TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell. 2008;133:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao Y, Ferrer J-L, Ljung K, Pojer F, Hong F, Long JA, et al. Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell. 2008;133:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang K, Feldman LJ. Regulation of root apical meristem development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:485–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.114753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowntree RA, Morris DA. Accumulation of 14C from exogenous labelled auxin in lateral root primordia of intact pea seedlings (Pisum sativum L.) Planta. 1979;144:463–466. doi: 10.1007/BF00380123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed RC, Brady SR, Muday GK. Inhibition of auxin movement from the shoot into the root inhibits lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1369–1378. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Xiong L. Pyridoxine is required for post-embryonic root development and tolerance to osmotic and oxidative stresses. Plant J. 2005;44:396–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, Xiong L. The short-rooted vitamin B6-deficient mutant pdx1 has impaired local auxin biosynthesis. Planta. 2009;229:1303–1310. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Last RL, Bissinger PH, Mahoney DJ, Radwanski ER, Fink GR. Tryptophan mutants in Arabidopsis: the consequences of duplicated tryptophan synthase β genes. Plant Cell. 1991;3:345–358. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernoux T, Wilson RC, Seeley KA, Reichheld JP, Muroy S, Brown S, et al. The ROOT MERISTEMLESS1/CADMIUM SENSITIVE2 gene defines a glutathione-dependent pathway involved in initiation and maintenance of cell division during postembryonic root development. Plant Cell. 2000;12:97–110. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukowitz W, Nickle TC, Meinke DW, Last RL, Conklin PL, Somerville CR. Arabidopsis cyt1 mutants are deficient in a mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase and point to a requirement of N-linked glycosylation for cellulose biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2262–2267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerk N, Feldman L. A biochemical model for the initiation and maintenance of the quiescent center: implications for organization of root meristems. Development. 1995;121:2825–2833. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerk NM, Jiang K, Feldman LJ. Auxin metabolism in the root apical meristem. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:925–932. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blilou I, Xu J, Wildwater M, Willemsen V, Paponov I, Friml J, et al. The PIN auxin efflux facilitator network controls growth and patterning in Arabidopsis roots. Nature. 2005;433:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature03184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]