Abstract

The rhizosphere is strongly influenced by plant-derived phytochemicals exuded by roots and plant species exert a major selective force for bacteria colonizing the root-soil interface. We have previously shown that rhizobacterial recruitment is tightly regulated by plant genetics, by showing that natural variants of Arabidopsis thaliana support genotype-specific rhizobacterial communities while also releasing a unique blend of exudates at six weeks post-germination. To further understand how exudate release is controlled by plants, changes in rhizobacterial assemblages of two Arabidopsis accessions, Cvi and Ler where monitored throughout the plants' life cycle. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) fingerprints revealed that bacterial communities respond to plant derived factors immediately upon germination in an accession-specific manner. Rhizobacterial succession progresses differently in the two accessions in a reproducible manner. However, as plants age, rhizobacterial and control bulk soil communities converge, indicative of an attenuated rhizosphere effect, which coincides with the expected slow down in the active release of root exudates as plants reach the end of their life cycle. These data strongly suggest that exudation changes during plant development are highly genotype-specific, possibly reflecting the unique, local co-evolutionary communication processes that developed between Arabidopsis accessions and their indigenous microbiota.

Key words: rhizobacterial succession, rhizobacterial communities, natural variation, root exudates, Arabidopsis accessions

Introduction

Plant roots are an active component of soil, creating the rhizosphere by physically changing soil characteristics as they elongate and branch out, and dramatically altering the chemical milieu through exudation of hundreds of phytochemicals and sloughedoff cells.1,2 Root-derived compounds mediate a plethora of biological processes. The plant-bacterial relationships that occur at the root-soil interface are probably a combination of opportunistic interactions, as ubiquitous organisms exploit the nutrients present, and highly regulated communication events. The latter interactions are mediated by root-exuded signalling molecules that elicit specific responses. The type and amounts of the various exudate compounds synthesized and released by roots are under the plant's genetic control, making plant genetic make-up one of the most significant determinants of rhizobacterial selection. Even opportunistic use of root exudates as metabolic fuel will attract only those bacteria equipped to make use of the nutrients that are extant and at the same time capable of adapting to the rhizosphere environment. The unique exudate cocktails released by different plant species therefore signal to and attract a specific bacterial assemblage in a reproducible manner, explaining the well established role of plant species in rhizobacterial community selection.3,4 Using various Arabidopsis thaliana accessions, we have previously shown that the plant genetic control of rhizobacterial recruitment is so tightly regulated that even genetic variants of the same plant species select for markedly different rhizobacterial assemblages.5 The eight Arabidopsis accessions used were shown to each release a unique combination of exudates when grown simultaneously under uniform conditions, resulting in genotype-specific rhizobacterial communities at six weeks post-germination.5 This study substantiates the genetic control of root exudation and highlights the signalling and communication mechanisms between plants and microbes driven by the plant's genetic code.

Presently, our insight of how plant genomes send signals into the rhizosphere is largely limited to a spatial understanding, and for the most part, lacks a temporal dimension. The rhizosphere however is a highly dynamic habitat characterized by an ever changing environment as a result of plant inputs. Arabidopsis genotypes mutated in their ability to induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR) showed differences in their rhizobacterial communities when compared to wild-type,6 suggesting that root exudation is dependant on plant responses to environmental triggers. Root exudates are also known to differ with plant developmental stage, both in composition and in relative quantities of each compound.2 Microbial succession, which refers to the sequential changes that occur in bacterial community structure, composition and functional diversity in response to environmental fluctuations, is in fact believed to be driven by nutrient availability,7 as physiologically diverse organisms capitalise on the available resources, and has been described for maize rhizospheres.8,9 Plant age has also been found to affect the level of polymorphism in a population of Burkholderia cepacia, a species which commonly associates with maize roots.10 To expand on the temporal aspect of exudate release and rhizobacterial development in response to plant-regulated changes, we took the approach of determining whether bacterial succession progresses differently in distinct Arabidopsis accessions. Such variation would be indicative of a specific response to a particular genotype's changing rhizosphere over time as a consequence of discrepancies in exudate composition. Simultaneously, it would confirm that the genotype-dependent rhizobacterial communities observed in the various Arabidopsis genotypes arise as a result of differential exudation throughout the plant life cycle and not as a consequence of asynchronous growth among accessions.

By using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) we compared the rhizobacterial community profiles of two Arabidopsis accessions, Cvi and Ler, which show divergent genotype-specific rhizobacterial communities at six weeks post-germination.5 Plants were grown as previously described5 and rhizobacterial fingerprints were monitored weekly for 8 weeks, throughout the entire life span of the plant. The bacterial profiles were reproducible for any given week but varied over time, revealing the influence of plant age on the development of bacterial communities associated with Arabidopsis roots. In addition, the two separate Arabidopsis genotypes differentially regulated the progression of rhizobacterial community succession.

The Effect of Age on Rhizobacterial Community Succession

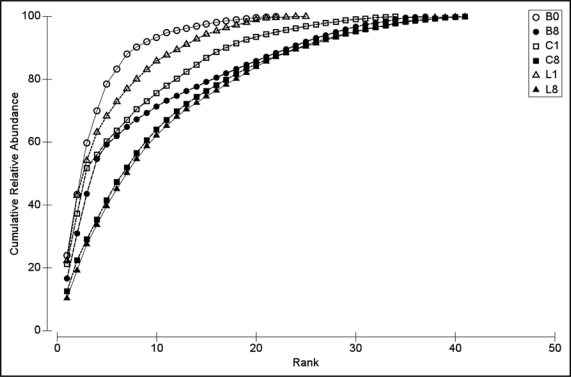

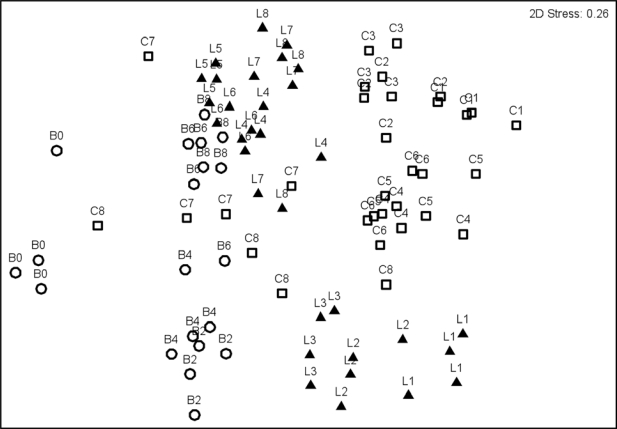

The emergence and disappearance of bands and variation in their intensity over time on DGGE gels revealed temporal changes in bacterial community structure as plants age. The number of DGGE bands (or ribotypes) detected in each sample, which when used comparatively gives a measure of how microbial diversity is changing over time, varied significantly and exhibited an overall increase. A temporal shift in bacterial community structure and composition was observed in all three communities studied—Cvi and Ler rhizospheres, and the bulk soil community. This successional change was indicated by a number of observations including ribotype richness, shifts in community structure denoted by dominance and evenness parameters (Fig. 1), and clustering of communities into discrete groups in relation to early, mid- and late phases of plant age (Fig. 2). The lowest ribotype richness was detected from bulk soil at week 0. Although bulk soil diversity rose progressively in response to soil wetting, the increase in ribotype number was higher in both Cvi and Ler accessions, as expected of a rhizosphere effect (Fig. 1). Cvi displayed a more pronounced and immediate change in microbial diversity than Ler at the onset of germination.

Figure 1.

k-dominance curves of cumulative % dominance against rank in decreasing order for average relative band intensities for control bulk soil at week 0 (B0) and week 8 (B8) (○ open and • closed circles, respectively), Cvi rhizosphere at week 1 (C1) and week 8 (C8) (□ open and ▪ closed squares, respectively) and Ler week 1 (L1) and week 8 (L8) (▵ open and ▴ closed triangles, respectively).

Figure 2.

Non-mertric MDS plot of bacterial communities of control bulk soil (B0-8, ○ open circles), and rhizosphere soils, Cvi (C1-8, □ open squares) and Ler (L1-8, ▴ closed triangles). Numbers denote the week.

To examine how the bacterial community structure changed over time, a series of k-dominance curves were plotted (Fig. 1). These curves plot the cumulative relative abundance of species in a sample against the increasing species rank and reveal evenness (equitability) and richness elements of a community. The bulk soil started off with a high position along the y axis indicating a low evenness and a limited spread across the x axis denoting a low ribotype richness. This curve corresponds to a community of lower diversity that is dominated by a few abundant ribotypes. The diversity of the Cvi rhizosphere community increased significantly with root emergence, as compared to the bulk soil from the previous week, indicating a strong and immediate rhizosphere effect in this accession. By week 8 both bulk and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities exhibited a higher ribotype richness and greater evenness, corresponding to communities with lower dominance, where the abundance is more evenly distributed among the ribotypes present. Both evenness and richness remained lower for the bulk soil however when compared to the rhizosphere communities.

Ordination of the data-set by non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS), performed as previously described,5 clearly separates the initial bulk soil communities from the rest of the samples (Fig. 2). The early rhizosphere communities of Cvi and Ler differed not only from each other but also from later communities from the same plant genotype. As plants from both accessions approached the end of their life cycle, their rhizobacterial communities converged together, as well as to late communities from bulk soil.

The Effect of Genotype on the Progression of Succession

The data demonstrate that the mechanism and rate at which rhizobacterial community succession progresses is highly dependent on plant genotype. Since exudation is known to differ for Cvi and Ler in 3 week old plants grown hydroponically,5 these novel results support our hypothesis that different Arabidopsis genotypes exhibit differential exudation patterns from the onset of germination and that this may affect the way that bacterial communities develop in the rhizosphere. The rhizobacterial assemblages of Cvi and Ler were divergent during early and mid-succession, the period of time during which plants are actively growing and rhizodeposition is expected to be most intense (Fig. 2). Thus, the plant genotype-dependent discrepancies in mature rhizobacterial assemblages previously reported by Micallef et al.5 are a result of natural variation in rhizospheric conditions generated by each accession, and not a consequence of asynchronous growth, an important observation, since Arabidopsis accessions exhibit a high degree of variability in several traits, including plant growth patterns and development.11

Ordination of the data by MDS (Fig. 2) accentuates the prominent impact of Cvi and Ler rhizospheres on bacterial communities. In addition, MDS highlights the pronounced genotypic differences between the two rhizosphere soils during early succession, when exudation is most profuse. As previously inferred, Cvi seemed to exhibit a stronger rhizosphere effect than Ler, implied from the tight clustering of Cvi communities in the MDS plot, up to week six (Fig. 2). On the other hand, MDS ordination places mid-succession communities from bulk soil and the Ler rhizosphere closer together as time progresses and by late succession they converge. This convergence was also eventually observed for Cvi, but to a lesser degree and only for the late successional stage (weeks 7 and 8). As the plants aged therefore, it seemed that the rhizosphere effect was attenuated even in Cvi.

Discrepancies in root exudation patterns and root system architecture (RSA) between Cvi and Ler could explain this variation. Regulation of root growth and RSA differ with genotype in Arabidopsis.12 Furthermore, exudation of carbon compounds is not uniform along the length of a root.13,14 Attempts at characterizing the RSA of the two Arabidopsis accessions used in this study were not made, since this trait is so elastic and highly sensitive to environmental cues.15 However, differences in primary root length and lateral root number between Cvi and Ler plants grown under the same conditions were typically apparent in more mature rhizospheres, three weeks or older (data not shown). These observations suggest that exudation patterns might be linked to RSA. At the onset of germination, therefore, dissimilarities in succession among various rhizobacterial communities could be initially influenced by disparities in exudation and later, as the rhizosphere network develops, also influenced by RSA and its affect on root exudation.

The multitude of Arabidopsis accessions that exist are variants originating from various geographical locations, adapted to their indigenous region.11 Hence, the discrepancies in exudation among Arabidopsis accessions may be indicative of co-evolutionary mechanisms that have occurred over time between plants and their local microbiota. Convincing evidence for specific plant-microbe interactions from various plant ecotypes might shed some light on this intriguing hypothesis in future studies. The significance of temporal variation in root exudation as plants age, on the other hand, remains unclear. We speculate that such changes may provide protection against pathogens, attract beneficial microorganisms and aid in nutrient absorption, all tailored to specific stages of plant growth, but more work needs to be done to provide evidence for specific processes occurring differently during a plant's life cycle. To further advance this field of study, the next step would be to dissect the genetic mechanisms by which Arabidopsis regulates exudation. Recent reports are showing that root exudation in Arabidopsis is an active process involving specific transporter molecules.16,17 Arabidopsis genotypes mutated in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter molecules had missing exudate compounds in their profiles relative to wild type16 and several transport systems were upregulated when roots were elicited with salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate.18 It is likely that qualitative differences in exudate profiles and temporal differences in release of phytochemicals among Arabidopsis accessions are brought about by differential regulation of transporters, in addition to differences in synthesis. Comparing rhizobacterial communities of different Arabidopsis genotypes mutated in specific transporter genes would further elucidate how exudation is regulated by plants and how bacterial communities in turn respond to these changes in plant communication. Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) are possibly involved in the complex regulation of exudate synthesis and release, which in turn dictate the type of bacterial assemblages that develop associated with the root system. Making use of the several recombinant inbred lines that are available for Arabidopsis, and using rhizobacterial responses as a measurable trait, would help locate regions of the Arabidopsis genome that regulate rhizosphere dynamics.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant to ACC from National Science Foundation (NSF) in collaboration with the Inter-Agency Program for Phytoremediation (Award No. IBN-0343856), and a NSF Undergraduate Mentoring in Environmental Biology Fellowship to SC (Award No. DEB-0080288).

Abbreviations

- DGGE

denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis

- MDS

multidimensional scaling

- RSA

root system architecture

- SAR

systemic acquired resistance

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/9229

References

- 1.Rovira A. Plant root exudates. Bot Rev. 1969;35:35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rovira AD. Plant root excretions in relation to the rhizosphere effect. Plant and Soil. 1956;7:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grayston SJ, Wang S, Campbell CD, Edwards AC. Selective influence of plant species on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:369–378. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma S, Aneja MK, Mayer J, Munch JC, Schloter M. Characterization of bacterial community structure in rhizosphere soil of grain legumes. Microb Ecol. 2005;49:407–415. doi: 10.1007/s00248-004-0041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micallef SA, Shiaris MP, Colón-Carmona A. Influence of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions on rhizobacterial communities and natural variation in root exudates. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1729–1742. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hein J, Wolfe G, Blee K. Comparison of rhizosphere bacterial communities in Arabidopsis thaliana mutants for systemic acquired resistance. Microb Ecol. 2008;55:333–343. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews JH, Harris RF. r- and K-selection and microbial ecology. Adv Microbial Ecol. 1986;9:99–147. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baudoin E, Benizri E, Guckert A. Impact of growth stage on the bacterial community structure along maize roots, as determined by metabolic and genetic fingerprinting. Appl Soil Ecol. 2002;19:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiarini L, Bevivino A, Dalmastri C, Nacamulli C, Tabacchioni S. Influence of plant development, cultivar and soil type on microbial colonization of maize roots. Applied Soil Ecology. 1998;8:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Cello F, Bevivino A, Chiarini L, Fani R, Paffetti D, Tabacchioni S, Dalmastri C. Biodiversity of a Burkholderia cepacia population isolated from the maize rhizosphere at different plant growth stages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4485–4493. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4485-4493.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Vreugdenhil D. Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loudet O, Gaudon V, Trubuil A, Daniel-Vedele Fo. Quantitative trait loci controlling root growth and architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana confirmed by heterogeneous inbred family. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;110:742–753. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDougall BM, Rovira AD. Sites of exudation of 14C-labelled compounds from wheat roots. New Phytol. 1970;69:999–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semenov AM, Bruggen AHCv, Zelenev VV. Moving waves of bacterial populations and total organic carbon along roots of wheat. Microb Ecol. 1999;37:116–128. doi: 10.1007/s002489900136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osmont KS, Sibout R, Hardtke CS. Hidden branches: developments in root system architecture. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.104006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badri DV, Loyola-Vargas VM, Broeckling CD, De-la-Pena C, Jasinski M, Santelia D, et al. Altered profile of secondary metabolites in the root exudates of Arabidopsis ATP-binding Cassette Transporter mutants. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:762–771. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loyola-Vargas V, Broeckling C, Badri D, Vivanco J. Effect of transporters on the secretion of phytochemicals by the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;225:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badri DV, Loyola-Vargas VM, Du J, Stermitz FR, Broeckling CD, Iglesias-Andreu L, Vivanco JM. Transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis roots treated with signaling compounds: a focus on signal transduction, metabolic regulation and secretion. New Phytol. 2008;179:209–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]