Abstract

We describe a case of secondary hypertension caused by renal arteriovenous fistula. An 8-year old girl was hospitalized with a severe headache, vomiting, and seizure. Renal angiography demonstrated multiple renal arteriovenous fistula and increased blood renin concentration in the left renal vein. Thus, left renal arteriovenous fistula and renin induced secondary hypertension were diagnosed. Her blood pressure was well controlled by medication with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.

Keywords: Hypertension, Renin, Arteriovenous fistula

Introduction

Hypertension in pediatric patients is either primary or secondary. Approximately 85-90% are more likely to have a secondary cause, whereas 90% of adult patients with hypertension are essential. Renovascular disease is an uncommon but important cause of hypertension in children and usually diagnosed after a long delay because blood pressure is infrequently measured in children.1) Congenital arteriovenous malformation and acquired arteriovenous fistula (AVF) are rare causes of secondary hypertension. Acquired AVF results from trauma, biopsy, surgery, malignancy, or inflammation.2) The prevalence of congenital renal AVF is less than 0.04% and consists of multiple irregular vessels without an associated elastic component.3) Congenital renal AVFs of the kidney are classified as either cirsoid or aneurysmal. The cirsoid type has a knotted, tortuous appearance with numerous feeding vessels and multiple interconnecting fistulas. The aneurysmal type has a single cavernous channel and well-defined arterial and venous elements, which can cause venous erosion.2),3) We present a case of hypertension secondary to congenital AVF managed by medication, and a brief review of the literature.

Case

An 8-year old girl visited a local clinic with a chief complaint of headache, vomiting, and seizure. She was found to be hypertensive upon admission for treatment of persistent nausea, vomiting, visual disturbance, and seizure, even with medication. She was referred to our department for further evaluation of hypertension. A family history of hypertension or renal disease were absent. History of drug abuse, surgery, trauma, malignancy, or renal biopsy was otherwise unremarkable.

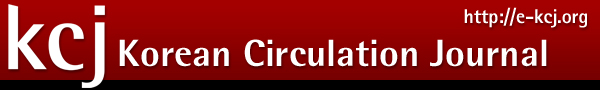

On physical examination, she was 127 cm tall (50 percentile) with a weight of 21 kg (5 percentile) and body mass index (BMI) of 13.02. Blood pressure in both upper and lower extremities were 160/100 mmHg (right) and 170/100 mmHg (left), respectively. She had no hematuria or abdominal and frank bruits. Chest radiography, echocardiogram, and abdominal ultrasound were unrevealing. Results from brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) raised suspicion of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI shows ill-defined high signal intensities (arrow) in T2 weighted image at both parieto-occipital cortical area.

Laboratory investigations showed normal biochemistry parameters, urinalysis, thyroid function tests, 24 hour urinary excretion of protein, and catecholamine. adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was normal. Serum renin was 22.6 ng/mL/hr (normal, 0.24-4.7 ng/mL/hr) and serum aldosterone was 68.33 ng/dL (normal 0.75-15.0 ng/dL). Serum epinephrine and norepinephrine were normal.

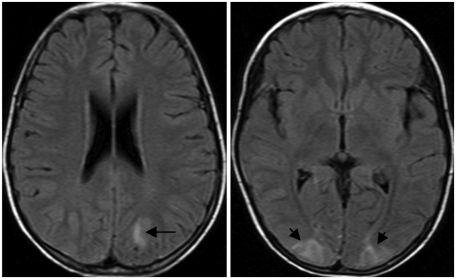

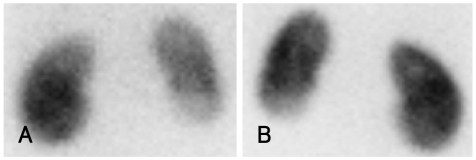

Kidney color Doppler sonography (US) showed neither stenosis nor obstruction in the renal artery. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) angiography (Fig. 2) and renal dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) single photon emission computed toraphy (SPECT) (Fig. 3) demonstrate decreased nephrogram and radioactivity of the lower pole of the left kidney.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal CT shows focal decreased nephrogram in left kidney lower pole anterior aspect, which indicated early renal infarcion or renal ischemia.

Fig. 3.

DMSA scan show decreased cortical uptake in the lower pole of left kidney (A: anterror, B: posterior). DMSA: dimercaptosuccinic acid.

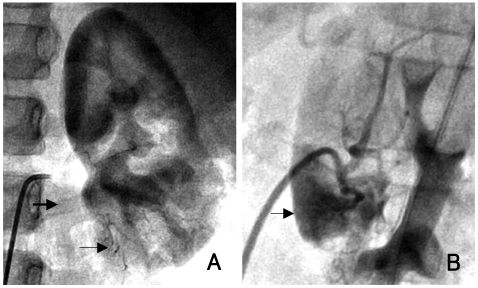

Diagnostic catheterization was performed, and there was no stenosis in either renal artery. Left renal angiogram showed multiple arteriovenous fistula and early filling of the left renal vein compared with the right, indicating the presence of an arteriovenous shunt (Fig. 4). Renal vein renin levels were obtained from both sides, as well as from the inferior vena cava. Serum renin level increased to 18.02 ng/mL/hr at the left inferior segmental vein, compared with 4.58 ng/mL/hr and 4.02 ng/mL/hr at the left anterosuperior segmental vein and right renal vein.

Fig. 4.

Anterior-posterior and lateral view of renal angiography shows multiple arteriovenous fistula (small arrow) and early visualization of renal vein (large arrow) compared to the right renal vein (A: anterior, B: lateral).

Diethylenetriamene pentaacetate (DTPA) nuclear renal scan and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) SPECT were normal.

We did not perform arterial embolization because lesions were multiple and there were some reports of spontaneous regression. The patient's blood pressure was well controlled by atenolol and enalapril and systolic blood pressure was maintained at 100-110 mmHg, and the patient is symptom free.

Discussion

Renal AVM is a rare occurrence, with only a little more than 250 reported in the literature; 70-80% of arteriovenous shunts are secondary results from surgery, trauma, malignancy of inflammation, and congenital AVF is reported in only about 50 cases. These lesions are almost always unilateral, predominant in the right kidney, and usually asymptomatic until adulthood. If symptomatic, hypertension, flank, and/or abdominal bruit or thrill, gross hematuria, and abdominal lumbar pain are the major symptoms. Congenital AVF is different from an acquired fistula in that it has a tortuous appearance of numerous vessels and multiple interconnecting fistulae, while acquired fistula usually presents as a single artery feeding directly, or via an aneurysmal dilatation of veins. These congenital vascular anomalies present with hematuria due to their location in the calyceal or pelvic submucosa, especially with the angiomatous variety.4),5) Hypertension is present in approximately 50% of patients with acquired fistulae, and 5% present as high output heart failure. Development of hypertension is believed to be the result of increased renin production secondary to renal parenchymal ischemia distal to the AVF due to shunting of blood. In our case, the presenting symptom is hypertension, and there is no hematuria.

Radiologic workup of a patient with suspected secondary hypertension may include color Doppler US, abdomen CT, radionuclear renography, and renal angiogram. Color Doppler US is the first time imaging procedure for renal AVM because of its low cost, less invasive nature, and wide availability. However, it may be difficult to distinguish arteriovenous fistula from aneurysm at color Doppler US, and flow in normal vessels grouped in the renal hilum obscures lighter-colored flow in a small central renal AVF. Although other diagnostic imaging tools might be helpful, angiography remains the standard of reference for confirming or excluding the existence of renal AVF, and selective segmental renal vein renin sampling is invaluable for locating the renin producing lesion.6-8)

Treatment should be considered when the patient is symptomatic, and embolization is the primary option, because it preserves maximal, unaffected, normal renal parenchyme while eliminating the risk of recurrent hemorrhage. The goal of AVF embolization is eradication of the nidus, where the artery and vein communicate. Recent reports describe the ablation of feeding vessels with various embolic agents, including absorbable gelatin sponge, absolute alcohol, polyvinyl alcohol, metallic coils, and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate.9-11)

There were some reports of spontaneous regression.12-14) However, the possible mechanism remains unknown. There were several hypotheses. Hemorrhage and hematoma may promote thrombosis and associated vasospasm and edema cause reduction of blood flow to the AVF. Increased blood flow disturbance may cause subacute or chronic thrombosis, leading to regression of AVF. Selective catheterization and angiography can damage arteriovenous malformation and result in the formation of thrombosis.

In our case, hypertension was successfully controlled by medication, and close follow up can avoid invasive treatment, such as embolization or partial nephrectomy, for the time being.

References

- 1.Tullus K, Brennan E, Hamilton G, et al. Renovascular hypertension in children. Lancet. 2008;371:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarif N, Mitwallil AH, Al Samayer SA, et al. Congenital renal arteriovenous malformation presenting as severe hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:291–294. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muraoka N, Sakai T, Kimura H, et al. Rare causes of hematuria associated with various vascular diseases involving the upper urinary tract. Radiographics. 2008;28:855–867. doi: 10.1148/rg.283075106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopalakrishnan G, Al-Awadi K, Bhatia V, Mahmoud AH. Renal arteriovenous malformation presenting as haematuria in pregnancy. Br J Urol. 1995;75:110–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen KJ, Chen CH, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Shu KH. Renal arteriovenous malformation in a young woman presenting with haematuria and hypertension. Nephrology. 2006;11:482–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goonasekera CD, Shah V, Wade AM, Dillon MJ. The usefulness of renal vein studies in hypertensive children: a 25-year experience. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:943–949. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0954-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tash JA, Stock JA, Hanna MK. The role of partial nephrectomy in the treatment of pediatric renal hypertension. J Urol. 2003;169:625–628. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000040339.75322.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh GY, Lee GH, Jeon DS, et al. A case of renal hypertension with unilateral renal artery stenosis and contralateral hypoplastic kidney. Korean Circ J. 1998;28:448–452. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crotty KL, Orihuela E, Warren MM. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of renal arteriovenous malformations and fistulas. J Urol. 1993;150:1355–1359. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takebayashi S, Hosaka M, Kubota Y, Ishizuka E, Iwasaki A, Matsubara S. Transarterial embolization and ablation of renal arteriovenous malformations: efficacy and damages in 30 patients with long-term followup. J Urol. 1998;159:696–701. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiesinger B, Schöber W, Tepe G, Erley C, Duda SH. Complication after embolization of a complex renal vascular malformation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1729–1733. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue T, Hashimura T. Spontaneous regression of a renal arteriovenous malformation. J Urol. 2000;163:232–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota H, Sakagami H, Kubota Y, Sasaki S, Umemoto Y, Kohri K. Spontaneous disappearance of a renal arteriovenous malformation. Int J Urol. 2003;10:547–549. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogazzi GB, Moriggi M, Fontanella U. Spontaneous renal arteriovenous fistula as a cause of haematuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:350–356. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]