Abstract

We report our progress on the development of new synthetic anti-cancer lead compounds that modulate the splicing of mRNA. We also report the synthesis evaluation of new biologically active ester and carbamate analogs. Further, we describe initial animal studies demonstrating the antitumor efficacy of compound 5 in vivo. Additionally, we report the enantioselective and diastereospecific synthesis of a new 1,3-dioxane series of active analogs. We confirm that compound 5 inhibits the splicing of mRNA in both cell-free nuclear extracts and in a cell-based dual-reporter mRNA splicing assay. In summary, we have developed totally synthetic novel spliceosome modulators as therapeutic lead compounds for a number of highly aggressive cancers. Future efforts will be directed toward the more complete optimization of these compounds as potential human therapeutics.

Introduction

The spliceosome is a critical component of the cellular machinery in higher organisms and has recently emerged as an important target for the discovery of selective anti-tumor agents.1 The complexity of the spliceosome rivals that of the ribosome; it is the part of the eukaryotic cell machinery responsible for the splicing of pre-messenger RNA to mRNA, and consists of U1, U2, U4/U6 and U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles and over one hundred and fifty associated proteins.2 An intricate arrangement of small nuclear RNAs and associated spliceosomal proteins interact with the pre-mRNA during spliceosome assembly, leading ultimately to intron removal, ligation of exons and the release of correctly processed mRNA. Two natural products have been recently reported to target the SF3b subunit of the spliceosome.3, 4 These naturally occurring compounds are pladienolide4 (PD,a actually a set of closely related compounds that have been designated pladienolides A-G, isolated from Streptomyces platensis)5 and 1 (FR901464)6 isolated from Pseudomonas sp. No 2663.6–8

The first of these natural products to be discovered (1) demonstrated significant efficacy in in vivo cancer models, but was chemically unstable and showed a relatively narrow therapeutic window.6 This prompted development of several types of partially stabilized compounds by modification of the hemiketal function of 1.9, 10 PD-based compounds (first reported in 2004) show a very promising combination of dramatic efficacy and very broad therapeutic window.4 Of seven naturally occurring PDs, pladienolide B has the most selective anti-cancer activity in vivo.5 Recently, a pladienolide B derivative 2 (E7107)4 entered clinical trials as an anti-cancer agent (see Figure 1).4 The natural products 1 and PD both show cytotoxicity with IC50s in the low nanomolar range against several tumor cell lines, and have been reported to cause a similar distinctive effect on the cell cycle in mammalian cell lines – cell cycle arrest that can occur at both the G1 and G2/M phases.5, 6 The interaction of these compounds with the spliceosome leads to what has been described as the inhibition of mRNA splicing, the inhibition of the nuclear retention of pre-mRNA, and the translation of unspliced mRNA, which ultimately results in the observed effects on the cell cycle.3, 4 The identification of the spliceosome as the target of 1 analogs was made possible through the application of a biotinylated derivative of 1 that was found to interact with the SAP155, SAP145 and SAP130 subunits of SF3b.3 The binding of these subunits to streptavidin beads loaded with the biotinylated 1 derivative was reversible. This result indicates that no irreversible covalent bond is formed via reaction of the epoxide group with these proteins, under these conditions, despite the natural initial expectation to the contrary.3 In the case of the elucidation of the mechanism of action of PD and related analogs, a slightly different approach was used: a doubly labeled affinity probe that cross-linked specifically to the SAP130 subunit was prepared, and from additional experiments it was concluded that SAP145 was required for the binding of the probe to SAP130.4

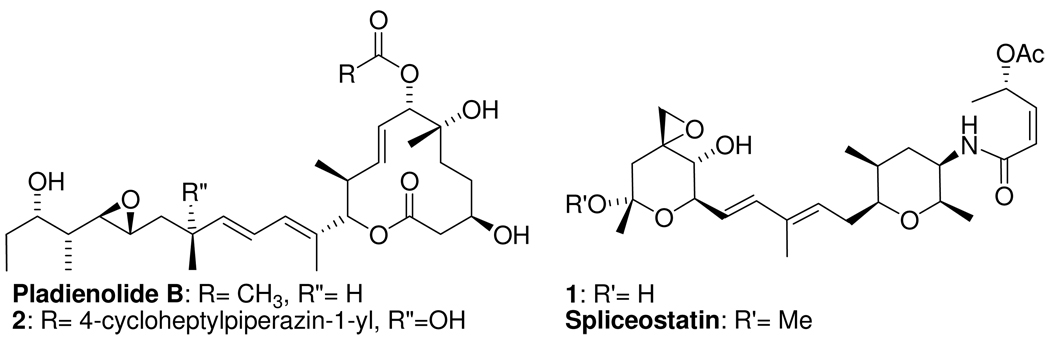

Figure 1.

The published structures of pladienolide B, 1 (FR901464), 2 (E7107) and spliceostatin.

Partially stabilized analogs of 1, such as spliceostatin (Figure 1), have been used to elucidate the effects of inhibition of the SF3b subunit on cell function.3 This work led to the observation that inhibition of SF3b by 1 analogs, or knockdown of SF3b by siRNA, are both associated with the same phenotypic changes in cells, and result in export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and translation of ‘unspliced’ or ‘incompletely spliced’ pre-mRNAs. One of the proteins aberrantly translated as a result of compound treatment (or siRNA knockdown of SF3b) is p27, resulting in accumulation of a truncated p27 in treated cells. The truncated p27 retains its activity as a cell cycle inhibitor but is not targeted for degradation by the proteasome due to deletion of part of its C-terminus that contains a phosphorylation site at threonine-187, which normally targets the protein for degradation once phosphorylated.11 Accumulation of this truncated, functionally intact, but degradation-deficient p27 in tumor cells contributes to their cell cycle arrest and potentially to the anti-cancer effects of SF3b modulation. It should be emphasized that these alterations of p27 represent only one of undoubtedly many (yet-to-be characterized) effects of spliceosome modulation on the expression of oncoproteins, tumor suppressors and other proteins that contribute to oncogenesis.

Previous work identified some of the structural requirements for activity in 1 and PD analogs, either by modification of the natural products,4 or by the total synthesis of some modified compounds (Figure 2).3, 10, 12 Prior studies have shown the orientation of the acetyl group and the presence of the epoxide to be important in conferring activity to 1 analogs,10, 13 and that the glycosidic hydroxyl group can be replaced by an alkoxy,14 or a methyl group,9 to give more stable compounds, or as in the latter case more stable and more active compounds9 (Figure 2). Active analogs of PD also contain similar functionality to that found in 1,4, 5 though less structure-activity information has been reported on these more recently discovered compounds.

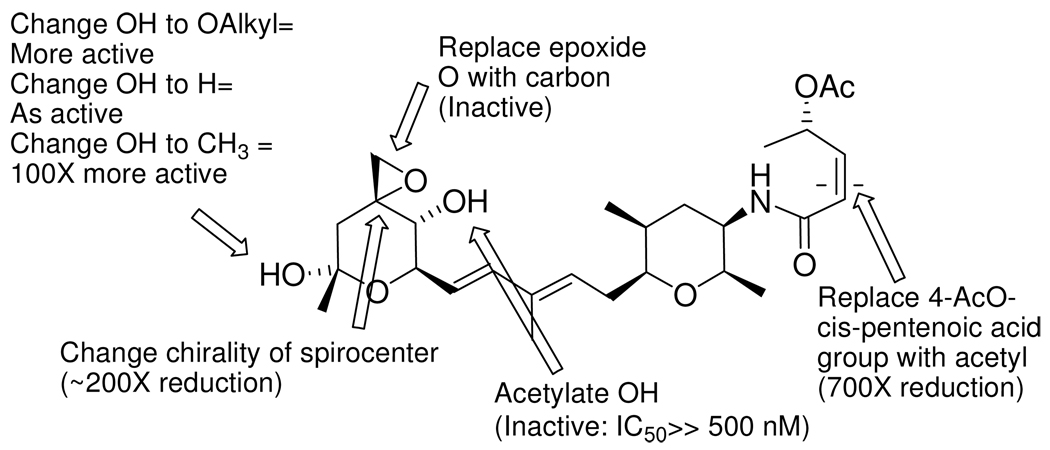

Figure 2.

An overview of some of the representative published data on SAR for 1 analogs.3, 10, 13 Activity is reported relative to 1.

We have recently published the design and enantioselective synthesis of active concise analogs of 1.15 Our analog design was founded on the recognition that 1 and PD have an apparently identical mechanism of action and present a similar pharmacophore.15 Molecular overlays of 1 and PD revealed that despite the gross dissimilarities between the two, both molecules share certain common key features (known to be critical to their activity) that can overlap in low energy conformations in three dimensions (Figure 3).15 Our published 3D pharmacophore model prompted our proposal that compounds of the general structure 3a, 3b and 3c (see Figure 4) should share a common pharmacophore with 1 and PD, and therefore might serve as starting points for development of both tool and lead compounds with potential application in human cancer therapy.15 The proposed compound 3a contains the unchanged methylpenta-2,4-diene and 5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl acetate groups along with the modified deoxy-spiroepoxide group, with the central pyran ring replaced with a cis-1,4-substituted cyclohexyl group, whereas compounds 3b and 3c include additional polar modifications to the methylpenta-2,4-diene group that are very synthetically accessible. These changes (particularly for compound 3a) were expected to impart similar conformational presentation of the linker, the epoxy and the carbonyloxy groups to that found in 1.

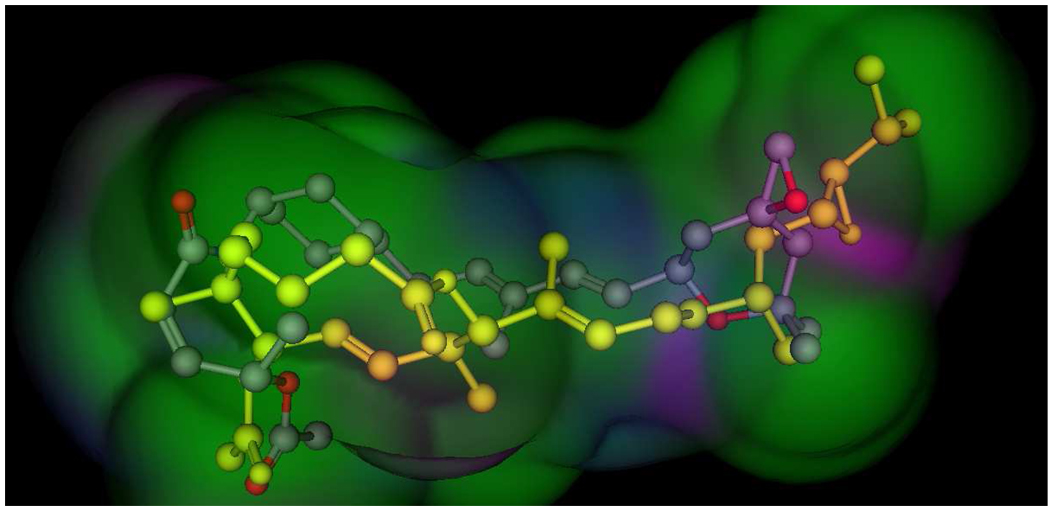

Figure 3.

A 3D representation of an example of an overlay of the presumed key interaction groups in a low energy conformation of pladienolide B (shown in yellow, some atoms have been removed for clarity) and compound 3a, showing that the epoxy group and the carbonyloxy groups are the same distance in both molecules. This figure includes a calculated Van der Waal interaction surface with the following color coding; purple= hydrogen-bonding, green= hydrophobic, blue= mildly polar.16 This alignment represents the best S value (S=167.18) for molecules matching the hypothetical pharmacophore, and the second best overall of 69 alignments from 500 iterations. The alignment was prepared using the Molecular Operating System (MOE 2007.09, Chemical Computing Group, Inc.) using the Flexible Alignment function with both molecules, following a conformational minimization using MOE default settings.17 18

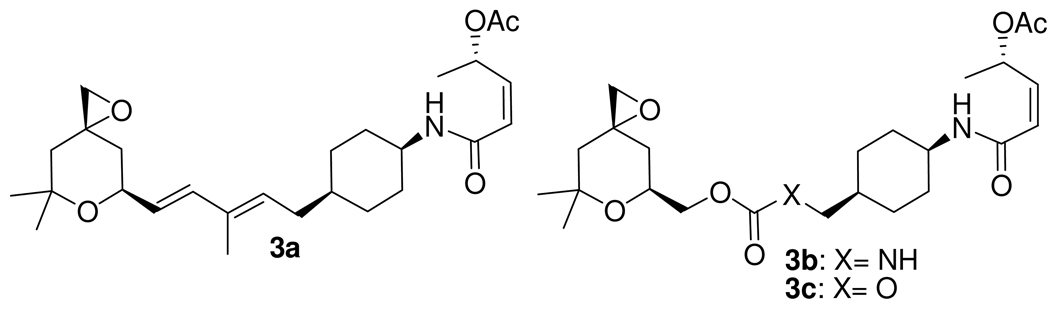

Figure 4.

Synthetic targets that matched a proposed spliceosome modulation pharmacophore.15

There have been numerous synthetic approaches to 1;12, 14, 19–22 however, since these approaches target the much more complex natural product, they were not highly instructive for the synthetic targets 3a, 3b and 3c. Our approach to these concise analogs provided compounds 3a, 3b and 3c enantioselectively and diasterospecifically in a highly step-efficient manner.15 Our recent report included initial data on the anti-tumor activity of compounds 3a, 3b and 3c against a small panel of human cancer cell lines.15 Compound 3a showed cytotoxic activity against all seven cancer lines in which it was initially assayed. In particular, compound 3a exhibited a cytotoxic IC50 of 100 nM against the JeKo-1 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) line, which was ~50-fold selective for this line compared to the A549 lung cancer cell line. By contrast, compounds 3b and 3c demonstrated only modest cytotoxic effects at the highest concentration in all cell lines tested (IC50 >5 µM).15 In summary, although compound 3a is less active than the natural products PD and 1 (that both possess GI50s in the single-digit nanomolar range against several tumor lines)5, 6 against certain cancer cell lines tested in common, compound 3a showed considerable activity (IC50< 5 µM) against all of the tumor lines examined and was especially selective and potent in the killing of the two MCL lines JeKo-1 and JVM-2.15 Additionally, we have reported that compound 3a has an effect on the cell cycle that is similar to that of the spliceosome modulator compounds PD and 1,15 which induce an accumulation of cells in G2/M, with a simultaneous decrease in the fraction of cells in S phase.3, 5, 6 In our current studies herein, we describe the design and synthesis of multiple analogs of compound 3a together with their biological characterization, including an initial demonstration of the in vivo anti-tumor activity of two of the analogs. Our approach is based on the idea that the availability of new analogs related to our synthetic scaffolds will allow for the discovery of drug leads that may circumvent the liabilities that are present in 1 or PD derivatives.

Results and Discussion

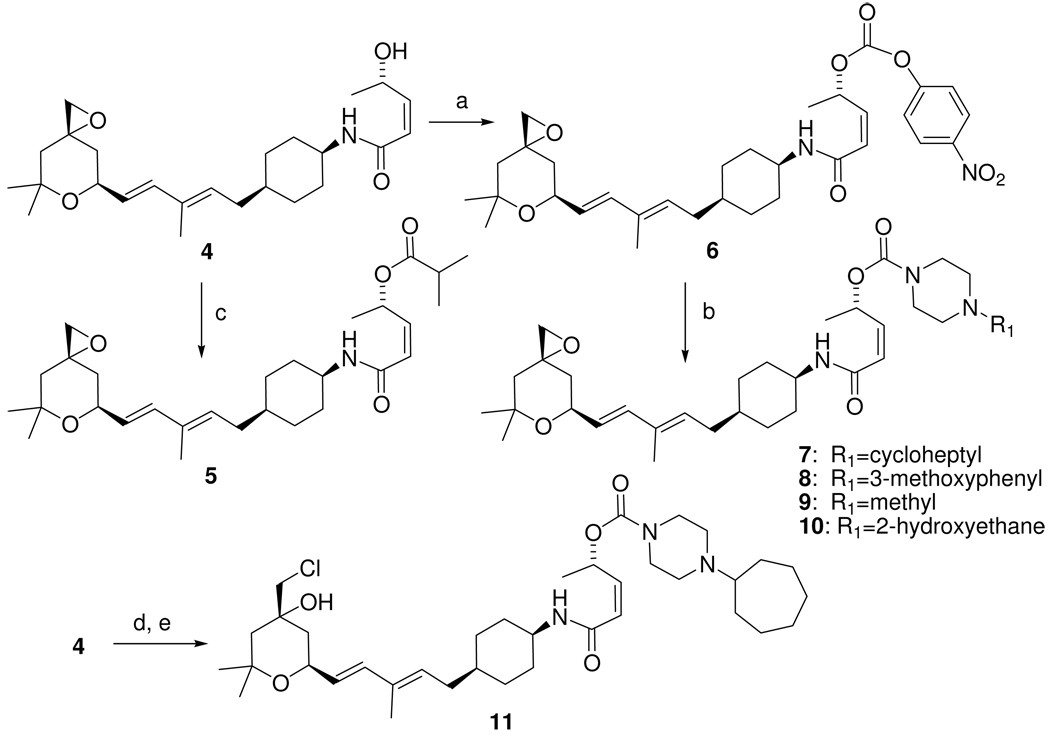

Modification of the ester group of compound 3a yields active novel compounds

In order to advance novel analogs of 1 as potential therapeutics for cancer we have initiated work directed toward establishing a more robust understanding of the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of compounds in this series. We knew that the diene portion of our scaffold was sensitive to some substitution by heteroatoms (see compounds 3b and 3c, Figure 4).15 We initiated experiments designed to test the hypothesis that 1 and PD (and compound 3c) share a common pharmacophore consisting of a carbonyloxy group (2 hydrogen-bond acceptors), a rigid diene linker (hydrophobic) and a potentially reactive secondary epoxide (electrophilic hydrogen-bond acceptor) arranged in a specific 3-dimensional orientation constrained by the possible overlap of 1, 3a and PD (see Figure 3).15 In addition to the acid-sensitive electrophilic epoxide group, both of the natural products 1 and PD contain an acetyl ester group that would be expected to have limited stability in vivo due to the susceptibility of ester groups to hydrolysis by ubiquitous plasma and cellular enzymes that exhibit ester hydrolase activity.23 Indeed, this acetyl has been replaced with a basic carbamate in the clinical compound 2 (Figure 1) that has been reported to have better in vivo activity compared to PD.4 The presence of significant esterase metabolic activity in vivo has been widely studied in the development of prodrug lead compounds,24 and is known to show significant species variability.25 Thus, our first experiments were directed toward experimentally testing the requirements for activity of analogs containing modifications of the O-acetyl and epoxide groups of compound 3a, using chemistry shown in Scheme 1. We first chose to replace the acetyl with the more hindered isobutyryl ester (compound 5) using the alcohol intermediate (compound 4) from our published synthesis of acetyl derivative 3a, since no information regarding such modifications has been published and because such hindered esters could be more stable in vivo.24 We next prepared carbamate derivatives that contain a basic amine group, since it is known that in pladienolide analogs such compounds (e.g. 2, Figure 1) maintain substantial in vivo activity, and indeed have entered clinical trials.4 This type of modification is expected to impart both improved solubility and esterase resistance to target compounds. In addition, good synthetic protocols exist for the preparation of carbamates of this type.26 The key intermediate in the preparation of these carbamates is carbonate 6, which was converted to basic carbamates 7–10 using the published protocol with minor modifications (Scheme 1).26 Additionally, it is known that the ‘epoxide-opened’ chloro-alcohol 1 derivative.6–8 and related derivatives also show activity in tumor growth inhibition like 1. To confirm the importance of the intact epoxide group for our analogs, we explored the synthesis of the ring-opened compound (11, Scheme 1), which is analogous to the known chloro-alcohol analog of 1.6–8

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of carbamate and ester analogs of compound 3a.b

bReagents and conditions: (a) 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate, Et3N, dichloromethane; (b) R1-piperazine, 1,2-dichloroethane; c) isobutyryl chloride, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2; (d) 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate, pyridine, THF/CH3CN; (e) (1-cycloheptyl)piperazine, 1,2-dichloroethane.

We then screened compounds 4, 5, and 7–11 for in vitro cytotoxicity and obtained the results shown in Table 1. Acylation of the alcohol formed ester 5, which retained potency similar to compound 3a. This compound was prepared with the expectation that it might have a longer half-life in mouse and human plasma, since it would be expected to be more resistant to esterases present in many biological fluids (see the subheading Chemical stability of compounds 3a and 5 below).24 It is interesting to note that the alcohol 4 shows a dramatic reduction in activity, when compared to the esters 3a and 5 (Table 1); this is very relevant to the in vivo activity of these compounds, since it is known that unhindered esters have a very limited half-life in mouse plasma in vivo. 24 The more hindered ester 5 demonstrates a similar in vitro cytotoxicity profile to that of compound 3a in every tumor line we have examined. Carbamate derivatives 7–10 showed significant reduction in cytotoxic activity by >5-fold, as in the case of the JVM-2 line (Table 1). The epoxide ring-opened compound (11) shows an additional reduction in activity in this case (see Table 1).6 For comparison, the literature contains only one report of an active carbamate PD analog (2), which is four-fold less active than pladienolide B.4 It should be noted that despite several very high quality total syntheses,9, 13, 14, 20, 22 the complexity of 1 has hindered development of extensive SAR data, and there have been no reports on the activity of corresponding 1 reference compounds to compare to most of the analogs in Scheme 1. For example, there are no reports on the synthesis, or bioactivity, of carbamate analogs of 1 to directly compare to carbamates 7–10. Our recent results are very useful for the design of compounds for evaluation in in vivo efficacy models since we now know it is relatively easy to prepare many more new ester derivatives that may have significantly different pharmacokinetic behavior yet still retain reasonably potent tumor cytotoxicity in vitro (see Scheme 2 below).

Table 1.

In vitro cytotoxicity screening data as determined by XTT for compounds from Scheme 1, following a 72-hour exposure. JeKo-1 and JVM-2, mantle cell lymphoma; PC-3, prostate adenocarcinoma; WiDr, colorectal adenocarcinoma.

| Compound number |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Cell line | IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 | ~ IC50 |

| (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | (µM) | |

| JeKo-1 | 0.10 | 1.6 | 0.12 | ND | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | ND |

| JVM-2 | 0.13 | 1.5 | 0.19 | >1.0 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >10.0 |

| PC-3 | 2.1 | 10 | 2.2 | >5.0 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >5.0 |

| WiDr | 2.0 | 10 | 0.91 | 4–5 | >1.25 | >1.25 | >1.25 | >1.25 |

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of new ester analogs.

Reagents and conditions; a) For compound 12 the corresponding acid, EDC and DMAP were used, in all other cases the conditions were acid chloride/Et3N/DMAP. In vitro cytotoxicity screening data as determined by XTT assays are shown for the compounds following a 72-hour exposure.

Increased chemical stability of compounds 3a and 5 compared to 1 or meayamycin

One of the goals of our initial animal studies is to modify the various pharmacodynamic properties of our analogs so that we may determine how this affects the efficacy and toxicity of spliceosome modulators in anti-tumor efficacy studies. We have noted that the biologically active compounds 3a and 5 are chemically stable in physiologic buffer (phosphate buffered saline, pH=7.4; t1/2= 1200 hours at 22 °C) and DMSO (no detectable decomposition after two weeks at 22°C), but are rapidly degraded in dilute aqueous acid. This is in marked contrast to the published stability of 1 (t1/2= 4.0 hours at 37 °C at pH 7.4)9 and analogs reported in the literature (the most stable of which has a t1/2= 48 hours at 37 °C at pH 7.4).9

Tumor cell line screening results; Compound 5 exhibits selective anti-tumor activity against certain adult and pediatric cancer types

Given our initial SAR data we sought to explore the sensitivity of tumor lines in the NCI 60 tumor cell line screen.27 This screen identified a number of lines that appeared to be particularly sensitive to compound 5 (see Supplemental Figure S1). Using the NCI 60 cell line screen as a starting point, we have begun to validate and determine the IC50 of compound 5 for various adult cancer types in addition to the cancer cell lines used in Table 1 (see Table 2, upper panel).

Table 2.

Compound 5 cytotoxicity determinations against various adult and pediatric tumor cell lines, and cells from normal tissues. The cells were treated with compound 5 for 72 hours and cytotoxicity was determined by XTT assay. Data represent the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) from three independent experiments.

| Cell line | Adult cancer type | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| SK-MEL-2 | Melanoma | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| SK-MEL-5 | Melanoma | 0.64 ± 0.07 |

| SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma | 0.55 ± 0.15 |

| MIA PaCa-2 | Pancreatic Carcinoma | 1.20 ± 0.12 |

| PANC-1 | Pancreatic Carcinoma | 3.87 ± 0.70 |

| Pediatric cancer type | ||

| MOLT-4 | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 0.08 ± 0.004 |

| Ramos | Burkitt's Lymphoma | 0.08 ± 0.008 |

| NB-1643 | Neuroblastoma | 0.23 ± 0.04 |

| MV-4-11 | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| Rh41 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| NB-EBc1 | Neuroblastoma | 0.66 ± 0.05 |

| SUP-B15 | B-cell precursor leukemia | 0.67 ± 0.14 |

| Rh30 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.69 ± 0.12 |

| SK-NEP-1 | Ewing Sarcoma | 0.70 ± 0.07 |

| SJ-GBM2 | Glioblastoma | 0.90 ± 0.09 |

| Karpas-299 | Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma | 0.92 ± 0.14 |

| BT-14 | Medulloblastoma | 1.34 ± 0.23 |

| BT-12 | Rhabdoid Tumor | 2.79 ± 0.12 |

| BT-3 | Medulloblastoma | 4.41 ± 0.26 |

| Normal tissue | ||

| PrEC | Normal Prostate Epithelial Cell | 7.01 ± 1.1 |

| HFF | Human Foreskin Fibroblast | >10 |

| Human Foreskin Fibroblast | ||

| HFF/tert2 | (immortalized) | 9.69 ± 0.09 |

In addition to adult cancers, we were also interested in the response of the pediatric malignancies, which by and large are completely different cancers than those that occur in adult patients, to this class of agents as well. Toward this goal, we selected a representative panel of cell lines derived from the more frequent childhood cancers for examination, with a special focus directed to the inclusion of those tumor types for which the prognosis remains poor, even following current best available clinical management (examples include high-risk neuroblastoma, MLL fusion-positive acute leukemia, and rhabdoid tumor).28–31 As shown in Table 2, middle panel, the pediatric cancer cell lines were, in general, sensitive to compound 5. Importantly, lines representing several poor-prognosis malignancies such as MLL-AF4-positive acute myeloid leukemia (MV-4-11) and high-risk neuroblastoma (NB-1643) were very sensitive to the cytotoxic activity of compound 5, with IC50 values of ~300 and 230 nM, respectively. Certain other pediatric tumor types that are also very aggressive but for which the prognosis is less dismal, if the patients undergo aggressive therapies that are frequently associated with both short- and long-term morbidity as well as occasional mortality, were quite sensitive. For instance, one example of such a tumor, Burkitt’s lymphoma, demonstrated marked sensitivity to compound 5 (cell line Ramos; IC50 ~80 nM). Although obviously quite preliminary, these data are nonetheless promising and suggest a potential role for spliceosome modulator therapy not only in the management of certain adult cancers but for selected pediatric malignancies as well.

To gain preliminary insight into the toxicity of these compounds in normal tissues, we also investigated the cytotoxicity of compound 5 in normal prostate cells and human foreskin fibroblasts (Table 2, lower panel). We found that in the PrEC (normal prostate epithelial cell) line compound 5 had an IC50 of 7.0 ± 1.1µM, and IC50 values of >10 µM and ~10 µM in the normal human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) and HFF/tert2 (HFF immortalized by expression of telomerase), respectively. These results indicate a significant selectivity of compound 5 for many tumor versus normal cell lines, even under cell culture conditions (e.g., compound 5 shows an IC50 of 0.08 µM for MOLT-4 acute T-cell leukemia and Ramos Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines under identical conditions, indicating a selectivity index of 125 or greater compared to the HFF cells).

Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity characterization of additional ester analogs of compound 3a

To follow up on the promising activity of ester analog 5, we next prepared a set of diverse ester analogs by acylation of alcohol 4 (Scheme 2). These ester derivatives were expected to give analogs with improved plasma stability or solubility, or both. As seen in Scheme 2, though highly polar modifications were not well tolerated, weakly basic groups could be abided with only a modest decrease in cytotoxic activity. Most interesting, additional branching of the hydrophobic group gave compound 19, which showed IC50 values of ~40 nM and 800 nM for the test cell lines JeKo-1 and PC-3, respectively (Scheme 2, lower right panel). Although we have yet to test the plasma half-life of compound 19, the additional hindrance imparted by the t-butyl group in this compound is expected to convey additional plasma stability, as was seen with isobutyryl ester 5.

Initial determination of a tolerated dose for compound 5

As a prelude to the in vivo efficacy and toxicity studies that we plan for our spliceosome modulators, we performed preliminary maximal tolerated dose (MTD) studies using compound 5 at doses ranging from 0 to 50 mg/kg (physico-chemical properties that limited the solubility of the compound using the formulation described below precluded the administration of higher doses). For this study, NOD/SCID mice (three per group) were dosed with vehicle, 5, 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg of compound 5 daily for five days by both IV and IP routes. Compound 5 was dissolved in 3.0% DMSO, 6.5% Tween 80 in 5% glucose solution, which is a modification of the formulation used by Mizui et al. for the spliceosome modulator pladienolide B.5 To determine compound-related toxicities, mice were monitored daily for weight loss, morbidity, and mortality. Following administration of the last dose of compound 5 on day 5, complete blood counts (CBCs) were determined along with a full diagnostic chemistry panel measuring albumin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), amylase, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), calcium, creatinine, globulin, glucose, phosphorous, potassium, sodium, total bilirubin, and total protein. No significant differences in blood cell counts were observed in treated versus vehicle-only mice, indicating that compound 5 is not associated with the induction of anemia, leukopenia or thrombocytopenia when administered under these conditions; likewise, no abnormalities of the blood chemistries were observed in the animals. The mice were monitored for one week following compound administration. No significant weight loss was observed in any group during or after compound administration. There was one fatality in the IP 25 mg/kg and one in the IV 50 mg/kg groups. It is unknown whether these deaths were due to compound-related toxicities or technical complications due to injections and/or bleeds for the CBCs and diagnostic panels; however, no fatalities were noted in subsequent efficacy studies employing these same compound 5 doses (see below), suggesting that technical complications were the likely cause. Total necropsies to assess organ histologies of animals from the various treatment and vehicle-only groups in these MTD studies showed no evidence for significant toxicities in the mice.

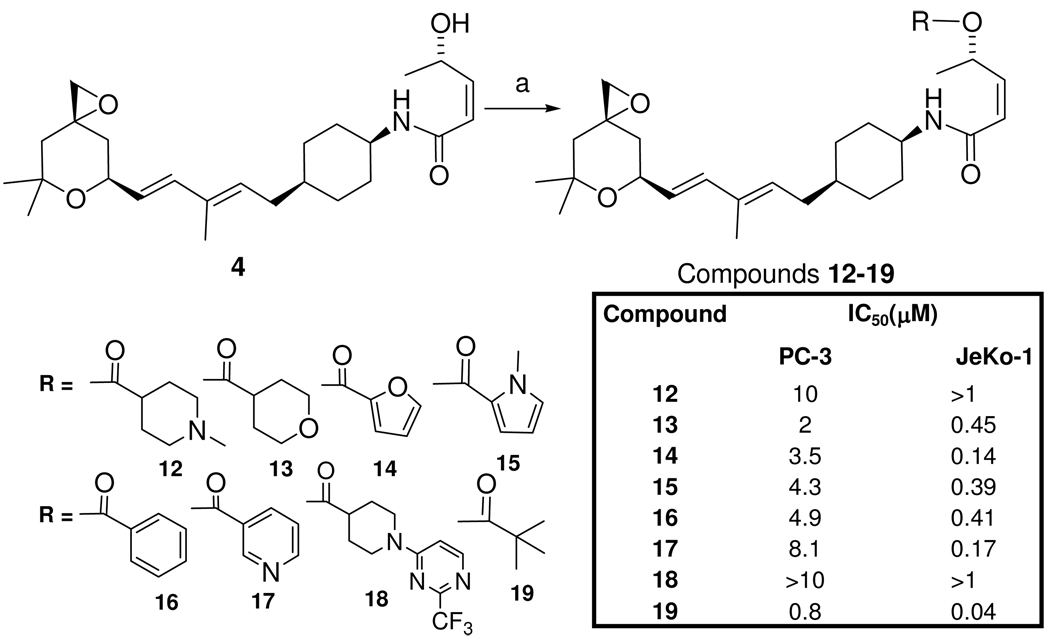

Initial in vivo efficacy studies

Following the MTD studies described above, we sought to determine whether the doses of compound 5 that we could readily administer were capable of inhibiting tumor growth in mice (Figure 5). For these studies, we transplanted JeKo-1 mantle cell lymphoma tumors (which we had found to be sensitive to spliceosome modulator compounds, as shown in Table 1) to NOD/SCID mice on day 1. Beginning on day 4, the mice received IV injections of vehicle, 5, 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg of compound 5 daily for five consecutive days. No fatalities or significant weight loss were observed in any of the groups (data not shown). Administration of 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg of compound 5 each led to statistically significant decreases in tumor volumes compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5). A widely used criterion for determining anti-tumor activity is tumor growth inhibition (T/C).32 This value is calculated by dividing the median tumor volumes of treated mice by the median volumes in control mice. According to NCI standards, a T/C ≤42% is the minimum requirement for activity.32 By performing this calculation, we determined that the 50 mg/kg compound 5 dose achieved a T/C value of 35%. Although preliminary, these data indicate that even a first-generation, minimally optimized compound from this series of spliceosome modulators could be administered at the doses necessary to inhibit tumor growth without observable toxicity. As shown below, we have already designed and prepared additional compounds with the goal of further increasing in vivo potency, solubility and selectivity for the spliceosome, in order to begin to optimize their anti-tumor potential.

Figure 5.

Compound 5 inhibition of tumor growth in JeKo-1 tumor-bearing mice. JeKo-1 mantle cell lymphoma tumors were transplanted to NOD/SCID mice on day 1 and, beginning on day 4, the mice (4 per group) received IV injections of vehicle, 5, 10, 25 or 50 mg/kg of compound 5 daily for five consecutive days. Vehicle alone did not inhibit tumor growth as compared to saline-treated mice (data not shown). Arrows indicate the dosing schedule. The data are represented as mean ± SEM. Tumor volumes were modeled with treatment, linear and quadratic trends over time, and interaction of treatment with linear and quadratic trends over time in a repeated measure framework using autoregressive 1 AR(1) variance-covariance structure and empirical sandwich error estimates for fixed effect. Significance is reported as the comparison of tumor volumes in vehicle-treated mice to compound-treated animals. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), Windows version 9.1. *, p = 0.01; **, p < 0.0001.

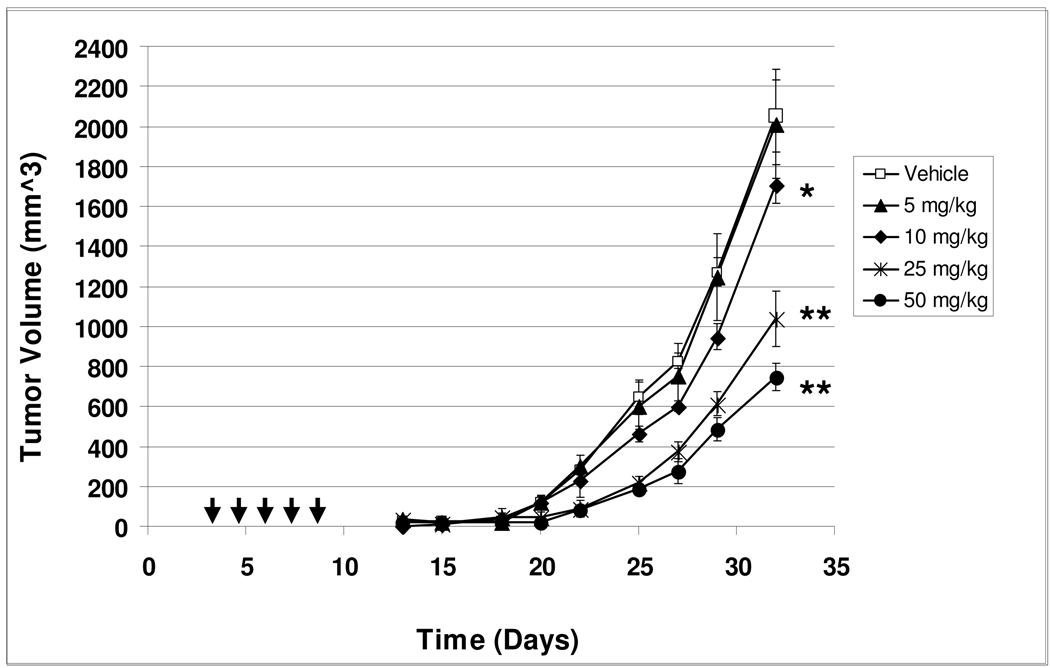

Synthesis of an active heteroatom modified scaffold related to compound 3a, with improved solubility

The activity of compounds 5 and 19 was promising but these compounds showed limited solubility in water or aqueous buffer (e.g., the measured solubility of 5 was less than 1 µM in PBS). Since improved solubility is desirable for both the formulation and in vivo distribution of drugs, we considered alternative approaches to the introduction of more polar groups to our lead structure. Since our attempts to obtain more soluble and potent (IC50<100 nM) analogs through the carbamate (Table 1) or polar ester (Scheme 2) approaches were not completely successful in the identification of compounds with both improved solubility and stability, we turned our attention to the introduction of more polar functionality into the scaffold of our lead compounds, without the addition of asymmetric centers. We envisioned (Scheme 3) that compounds such as the cyclic acetal 26, in which the cyclohexane ring is replaced with a 1,3-dioxane ring, would be substantially more soluble. Though the acetal is acid-sensitive, we surmised that this would not be an issue since intravenous infusion will be the most likely method of dosing in both animal model experiments and the clinical setting.

Scheme 3.

The synthesis of 1,3-dioxane analogs.b

bReagents, conditions and yields; a) 1H-imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide HCl, CuSO4·5H2O, K2CO3, MeOH; b) CF3COOH/H2O/CHCl3; c) ylide (shown), benzene; d) 1) DIBAL-H, CH2Cl2; 64% overall; 2) 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, Ph3P, DIAD, THF, 0 °C; 3) (NH4)6Mo7O24 tetrahydrate/ H2O2; 78% overall e) LiHMDS then aldehyde 24; 37% f) 1) Ph3P, H2O, benzene, 45 °C; 2) (S,Z)-4-(TBSO)pent-2-enoic acid, HBTU, iPr2EtN; 69% overall 3) TBAF, THF; 47% 4) Isobutyric anhydride, Et3N, DMAP; 96%; g) 1) Ph3P, H2O, benzene, 45 °C; 2)Acetic anhydride/pyridine.

The azido sulfone intermediate 23 was prepared from commercially available 1,1,2,2-tetramethoxy propane and 2-amino-1,3-propane diol via a selective transketalization reaction to give a known amino-acetal,33 which is obtained exclusively as the cis-product, as shown in Scheme 3. This amine was converted into the corresponding azide 20,34 which was then converted to the aldehyde 21 by selective hydrolysis of the dimethyl acetal functionality via TFA/H2O (19.5:0.5) in CHCl3. This aldehyde was further elaborated with the Wittig ylide (Scheme 3 step c) to give ester 22, which was reduced by DIBAL-H to provide the alcohol derivative that was converted to the corresponding Julia-Kocienski olefination reagent35 via a sequential Mitsunobu reaction with the 2-mercaptobenzothiazole anion followed by oxidation of the resulting sulfide with ammonium molybdate and hydrogen peroxide to give the sulfone derivative 23 in moderate yields.

The subsequent synthetic steps then utilize and improve upon the chemistry we have published. The azide sulfone 23 intermediate was then treated with an aldehyde 24 (prepared as published15) in the presence of LiHMDS (1.1 eq) to give the key azide diene intermediate 25. The azide group in this diene was then reduced to the corresponding amine using Ph3P and H2O, and this step was followed by amidation with the protected hydroxyl-cis-pentenoic acid to give the corresponding amide derivative. Cleavage of the TBS group in diene was accomplished with tetrabutylammonium fluoride at 0 °C and the resulting alcohol was then treated with isobutyric anhydride to afford the final analog 26. The overall yield of compound 26 using this approach was similar to that obtained for the synthesis of 5 (see Scheme 1). This compound showed in vitro activity similar to that of compound 5 (e.g., JeKo-1 IC50 = 150 nM); furthermore, an in vivo treatment trial using JeKo-1 tumor-bearing mice revealed compound 26 to possess robust anti-cancer activity that was comparable to compound 5 (see Supplemental Figure S2). As we had hoped, the solubility of this 1,3-dioxane derivative was significantly improved (measured solubility = 47 µM in PBS, which is >50-fold more soluble than the cyclohexane derivative 5).

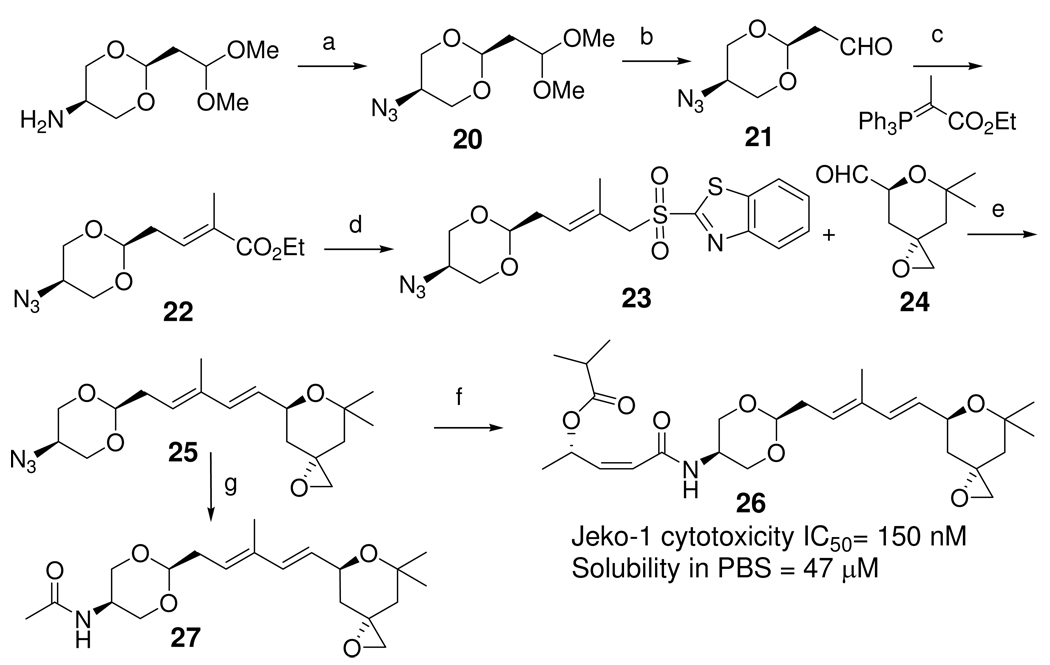

Experimental demonstration of splicing modulation by compounds 5 and 26

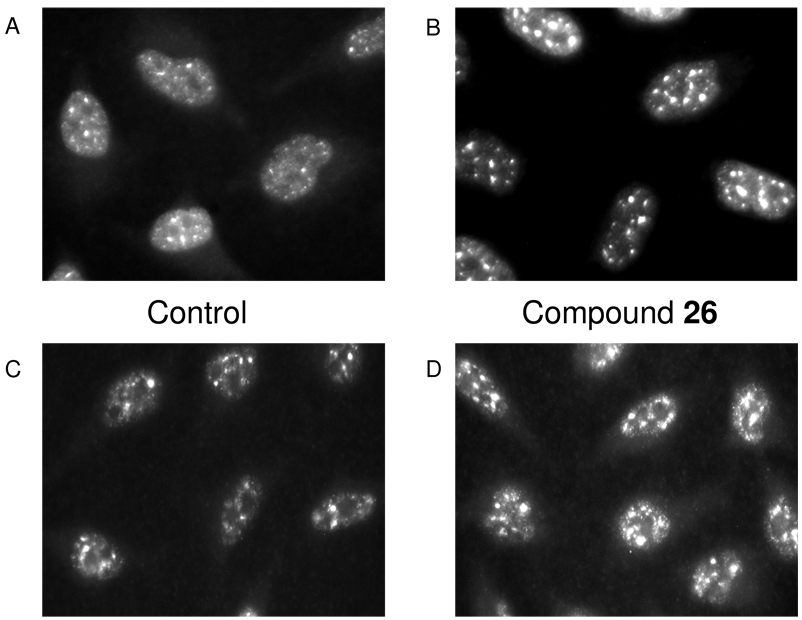

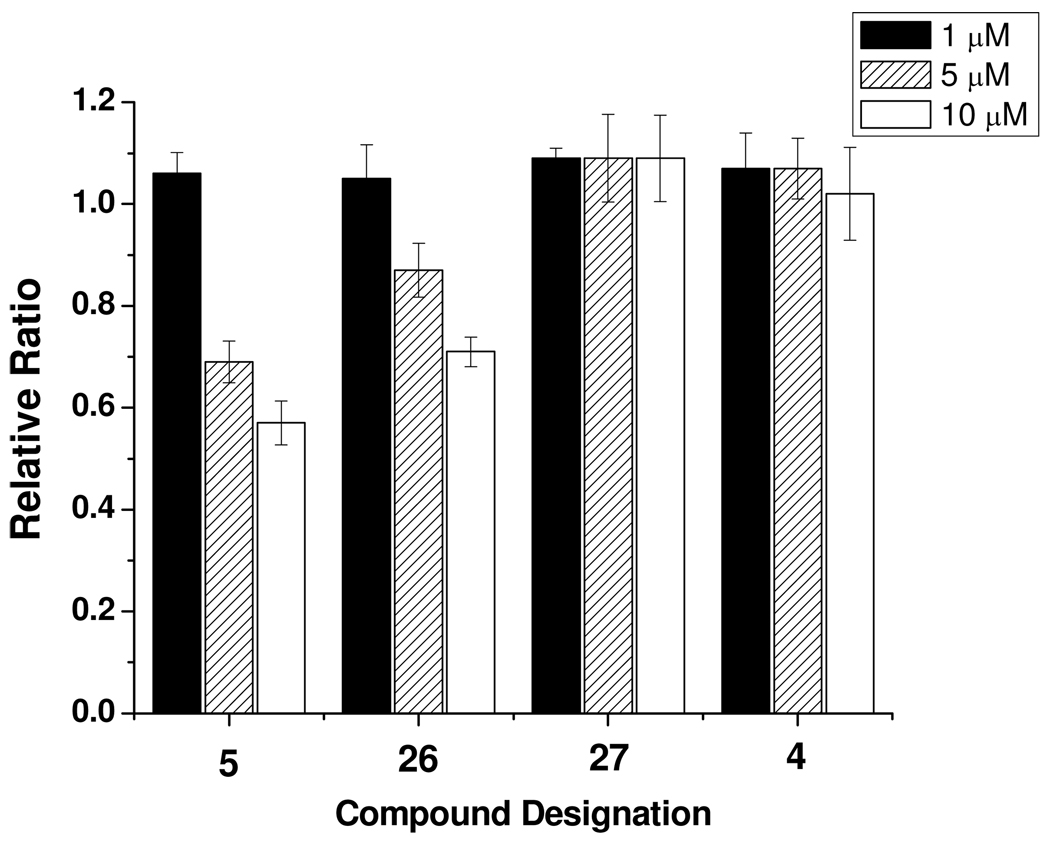

As an initial step in determining whether these new compounds affect splicing, we treated HeLa cervical carcinoma cells with 10 µM compound 26, the most soluble compound, for 4 hours and examined the effects of this drug on the localization of splicing factors in vivo using immunofluorescence analysis and antibodies recognizing the general splicing factor SC35 and SF3b3 (SAP155). These studies revealed that compound 26 caused the splicing factors to form large aggregates, which were similar to those reported in the literature to be observed in cells treated with either PD or 1 (Figure 6).3,4 To confirm that our new compounds were functioning as spliceosome modulators in a manner similar to PD and 1, we tested them in a dual-reporter assay that directly measures the effects on splicing in cells (Figure 7).36, 37 Lastly, as an additional means to conclusively demonstrate that our compounds alter splicing, we also performed an in vitro cell-free splicing assay that demonstrated compound 5 to inhibit the mRNA splicing activity of a HeLa nuclear extract (see Supporting Information Supplemental Figure S3).38, 39

Figure 6.

Compound 26 causes aggregation of the splicing factor SC35 and the SF3b protein SAP155. HeLa cells were incubated for 4 hours in culture media containing 10 µM compound 26 in DMSO (B and D) or an equal volume of DMSO (A and C) and stained with antibodies recognizing SC35 (panel A and B) or SAP155 (C and D). The cells were then stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies and examined with a fluorescence microscope using an objective with 60X magnification.

Figure 7.

Compounds 5 and 26 selectively inhibit splicing. 293T cells were transiently transfected with a dual-reporter splicing construct (see Experimental Section for details) for 48 hours and subsequently treated with or without compound for 5 hours. The degree of cell death was negligible at this time at the above tested concentrations. The cells were lysed, and equalized amounts of total cellular proteins were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity using the Dual-Light System. The data are expressed as the relative ratio of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity compared to a control vehicle (DMSO)-treated sample, and are presented as the mean ± SEM from multiple independent experiments. Note that compound 27 (which lacks cytotoxic activity; data not shown) had no effect in this assay, and that compound 4 (which exhibits only minimal cytotoxic effects at these concentrations; see Table 1) altered splicing only very slightly at the highest concentration tested; thus, the cytotoxic effects of our compounds correlate closely with their effects on splicing.

Conclusions

We have reported our progress on the development of new synthetic anti-cancer lead compounds that are concise analogs of the natural product 1. These novel compounds contain only three chiral centers, which is six less than the natural product, and were designed based on our recognition of a common spliceosome modulatory pharmacophore in both 1 and PD. Our design process integrates pharmacophore information with the simultaneous execution of synthetic step-efficiency and the application of enantioselective and diastereospecific synthetic approaches. This type of design approach allows for the ‘molecular concision’ of complex natural products into more approachable synthetic targets. This in turn makes possible a more robust synthetic examination of numerous features of the spliceosome pharmacophore, which have not previously been investigated.15 We present data that demonstrate these natural product analogs to be substantially more chemically stable than either 1 or the previously reported stabilized active analog meayamycin.9 We have developed active ester and carbamate analogs of our initial compound 3a, including the equipotent hindered ester 5, that have new diverse steric and physical properties with a range of cytotoxic activity. We have explored the scope of selective anti-tumor cytotoxic activity of 3a and 5 and discovered a number of sensitive adult and pediatric tumor lines, which include leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma and pancreatic carcinoma lines, among others. These findings led to some initial anti-tumor efficacy studies with compound 5 that clearly demonstrate significant in vivo inhibition of JeKo-1 tumor growth in immunocompromised mice following only five single daily IV doses. Additionally, we have reported the enantioselective and diastereospecific synthesis of a new template for active analogs (represented by 26) with significant improvements in measured solubility, which dramatically facilitates the formulation of these compounds for intravenous dosing. In vivo efficacy in a JeKo-1 tumor regression study has also been observed with compound 26 following a minimal five-day dosing schedule. We also report for the first time that compound 5 inhibits the splicing of mRNA in cell-free nuclear extracts. Data are also presented showing that these compounds selectively inhibit mRNA splicing in a dual-reporter cell-based splicing assay, and there appears to be a close correlation between cytotoxicity and the inhibition of splicing by the compounds tested. In summary, we have developed a totally synthetic novel spliceosome modulator as a lead compound as one step in the development of new treatments for a number of highly aggressive cancers. Future efforts will be directed towards the more complete optimization of these compounds as potential human therapeutics.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

General Aspects

All materials and reagents were used as is unless otherwise indicated. Air- or moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere. THF, toluene, acetonitrile, N,N-dimethyl formamide and CH2Cl2 were distilled before use. Flash column chromatography was performed according to Still’s procedure using 100–700 times excess 32–64 mm grade silica gel. TLC analysis was performed using glass TLC plates (0.25 mm, 60 F-254 silica gel). Visualization of the developed plates was accomplished by staining with ethanolic phosphomolybdic acid, ceric ammonium molybdate, or ethanolic ninhydrin followed by heating on a hot plate (120 °C). All tested compounds possessed a purity of >95% as determined by ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography on a Waters Acquity UPLC/PDA/ELSD/MS system carried out with a BEH C18 2.1 × 50 mm column using gradient elution with stationary phase: BEH C18, 1.7 mm, solvents: A: 0.1% formic acid in water, B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker Avance II 400 MHz. The values dH 7.26 and dC 77.0 ppm were used as references for NMR spectroscopy in CDCl3. The coupling constants deduced in 1H NMR data cases were obtained by first-order coupling analysis. Analytical and preparative SFC (Supercritical Fluid Chromatography) systems (AD-H and OD-H columns) were used for analysis and purification. IR spectra were collected using a Nicolet IR 100 (FT IR). FT IR analyses were prepared as neat and neat films on KBr plates, and the data are reported in wave-numbers (cm-1) unless specified otherwise. The University of Illinois Mass Spectroscopy Laboratories collected the high resolution mass spectral data.

Abbreviations: EDC, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide); DIAD, diisopropyl azodicarboxylate; DIBAL H, diisobutylaluminium hydride; TBAF, tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

(S,Z)-5-((1R,4R)-4-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)cyclohexylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl isobutyrate (5)

A solution of the alcohol derivative 4 (215 mg, 0.52 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was allowed to stir at 0 °C as Et3N (0.36 mL, 2.63 mmol) and DMAP (12 mg, 0.10 mmol) were sequentially added. After 5 min, isobutyryl chloride (0.16 mL, 1.58 mmol) was added drop-wise. The resulting solution was allowed to stir for 30 min at this temp. The reaction mixture was then diluted with water (10 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was again extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL), brine (20 mL), and then dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated and the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography (30% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 215 mg (84%) of 5 as a white viscous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.25 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H),6.27 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (d, 11.8 Hz, 1H), 5.78-5.72 (m, 1H), 5.63 (dd, J = 11.8, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.50-4.42 (m, 1H), 4.16-4.09 (m, 1H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.58-2.49 (m, 1H), 2.12-2.04 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 2H), 2.03 – 1.86 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 1.72-1.66 (m, 1H), 1.64 – 1.54 (m, 6H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.36 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.25-1.19 (m, 3H) 1.17 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H), 1.14 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.36, 164.87, 137.59, 136.22, 133.77, 132.06, 126.97, 125.62, 73.04, 69.59, 68.97, 55.69, 51.05, 45.31, 42.46, 38.64, 36.60, 34.44, 34.00, 31.55, 29.58, 29.47, 27.84, 27.54, 23.77, 20.30, 18.98, 18.86, 12.49; IR (Neat Film) 3314, 2973, 2931, 2856, 1733, 1688, 1628, 1533, 1450, 1368, 1241, 1195, 1047 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C29H46NO5 (M+1)+ 488.3376, found 488.3364

(S,Z)-5-((1R,4R)-4-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)cyclohexylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl 4-nitrophenyl carbonate (6)

A stirred solution of alcohol 4 (45 mg, 0.108 mmol) in anhyd CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was treated with Et3N (30 µL, 0.21 mmol) and 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (32.6 mg, 0.16 mmol) at room temperature. The resulting light yellow suspension was allowed to stir for 4h at room temperature. This mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and washed with aqueous 1N HCl (8 mL), saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (8 mL) and brine (8 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Concentration and purification of the residue by flash chromatography (30–40% ethyl acetate in hexane) gave 36 mg (57%) of 6 as a liquid; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.38 – 8.19 (m, 2H), 7.49 – 7.33 (m, 2H), 6.32 – 6.22 (m, 2H), 6.11 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (dd, J = 11.6, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (dd, J = 11.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.54 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.45 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (ddd, J = 11.0, 6.7, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (s, 1H), 2.58 (s, 2H), 2.04 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.98 – 1.88 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.63 – 1.57 (m, 6H), 1.53 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.25 – 1.13 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.12, 155.51, 151.90, 145.36, 140.14, 136.10, 133.94, 131.63, 127.19, 125.27, 124.76, 121.75, 74.38, 73.08, 69.59, 55.69, 51.06, 45.58, 42.46, 38.63, 36.38, 34.14, 31.54, 29.39, 29.32, 27.87, 27.71, 23.79, 20.05, 12.50; IR (Neat Film) 3316, 2974, 2930, 2856, 1766, 1668, 1631, 1526, 1347, 1256, 1215, 1048 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C32H43N2O8(M+1)+ 583.3019, found 583.3028.

(S,Z)-5-((1R,4R)-4-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)cyclohexylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl 4-cycloheptylpiperazine-1-carboxylate (7)

A solution of the activated carbonate (6) (4.2 mg, 7.21 µmol) in 1,2 dichloroethane (0.2 mL) was allowed to stir at room temperature as 1-cycloheptyl piperazine (0.21 mL, 0.02 mmol, 0.1M stock solution) was added. The resulting solution was stirred for 75 min and the solvent was then removed under vacuum. The crude was purified by flash chromatography (2–3% MeOH in CH2Cl2) to give 1.2 mg (27%) of 7 as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 – 8.08 (m, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 5.64 – 5.47 (m, 4H), 4.55 – 4.40 (m, 1H), 4.20 – 4.07 (m, 1H), 3.46 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 2H), 2.10 -2.03 (m, 2H), 2.02 – 1.87 (m, 2H), 1.83 – 1.76 (m, 2H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.65 – 1.50 (m, 14H), 1.47 – 1.43 (m, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.34 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.25 – 1.14 (m, 5H); IR (Neat Film) 3300, 2926, 2855, 1668, 1535, 1434, 1372, 1244, 1121, 1049 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C37H60N3O5 (M+1)+ 626.4533, found 626.4546.

(S,Z)-5-((1R,4R)-4-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)cyclohexylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl 1-methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate (12)

A solution of alcohol derivative 415 (10 mg, 0.024 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.22 mL) was treated with 1-methylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid (9.3 mg, 0.065 mmol), diisopropylethylamine (13 µL, 0.072 mmol), and DMAP (7.3 mg, 0.06 mmol). The resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C and treated with solid EDC (11.4 mg, 0.06 mmol). The resulting suspension was allowed to stir at room temperature for overnight. Saturated aqueous NH4Cl (1 mL) was added and the product was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×5 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (3 mL) and brine (3 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. This was concentrated and the residue was purified by flash column (5% MeOH in CHCl3 w/ 0.2%Et3N) to give 5 mg (39%) of 12 as a viscous liquid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.04 (bd, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 5.90 – 5.74 (m, 2H), 5.71 – 5.42 (m, 3H), 4.46 (ddd, J = 11.1, 6.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (m, 1H), 2.82 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 2H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.28 (s, 4H), 2.12 – 1.90 (m, 9H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.70 – 1.66 (m, 2H); 1.64-1.54 (m, 6H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.34 (d, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H), 1.26-1.12 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.07, 164.78, 138.02, 136.22, 133.80, 132.02, 127.00, 125.50, 73.05, 69.61, 69.17, 55.70, 54.81, 51.06, 46.28, 45.86, 45.37, 42.47, 38.65, 36.60, 34.42, 31.55, 29.55, 29.44, 28.07, 27.87, 27.60, 23.78, 20.27, 12.52; IR (Neat Film) 3284, 2927, 2853, 1729, 1666, 1628, 1533, 1449, 1374, 1218, 1182, 1047 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C32H51N2O5 (M+1)+ 543.3798, found 543.3784.

General Procedure for the preparation of ester derivatives from alcohol 415 using a variety of acid chlorides

A stirred solution of the alcohol derivative 415 (10 mg, 0.52 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL) at 0 °C was sequentially treated with Et3N (16.6 µL, 0.12 mmol) and DMAP (4.8 µL, 0.10 mmol, 0.5M in CH2Cl2). After 5 min at 0 °C, the appropriate acid chloride (0.07 mmol) was added drop-wise. The resulting solution was then allowed to stir for 1 h at the same temp. The reaction mixture was then diluted with water (3 mL) and CH2Cl2 (6 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×5 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (3 mL) and brine (3 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated and the crude residues were purified by flash chromatography (ethyl acetate in hexane) to give corresponding ester derivatives.

(S,Z)-5-((1R,4R)-4-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)cyclohexylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-carboxylate (13)

Yield: 8 mg (63%) of 13 as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.00 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 5.93 – 5.83 (m, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 5.65 (dd, J = 11.7, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.52 – 4.40 (m, 1H), 4.11 (s, 1H), 3.96 (dt, J = 11.6, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 3.43 (td, J = 11.3, 2.9 Hz, 2H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.56 – 2.47 (m, 1H), 2.10-2.04 (m, 2H), 2.02 – 1.87 (m, 2H), 1.86 – 1.74 (m, 4H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.71-1.65 (m, 1H), 1.64-1.55 (m, 6H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.37 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.26-1.12 (m, 4H), 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.60, 164.71, 138.11, 136.19, 133.81, 131.97, 127.05, 125.45, 73.05, 69.60, 69.30, 67.04, 67.02, 55.69, 51.05, 45.38, 42.46, 40.14, 38.64, 36.56, 34.42, 31.55, 29.72, 29.54, 28.64, 28.59, 27.88, 27.60, 23.78, 20.25, 12.52; IR (Neat Film) 3319, 2927, 2853, 1731, 1668, 1629, 1533, 1447, 1378, 1184, 1093, 1046 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C31H48NO6 (M+1)+ 530.3482, found 530.3481

(2s,5s)-5-azido-2-(2,2-dimethoxyethyl)-1,3-dioxane (20)

To a solution of (2s,5s)-2-(2,2-dimethoxyethyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-amine33 (59.8 g, 313 mmol) in MeOH (1.5 L) at 0 °C was added K2CO3 (86 g, 625 mmol), CuSO4·5H2O (780 mg, 3.13 mmol) and 1H-imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide-HCl (65.3 g, 375 mmol). The reaction was warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated and diluted with water. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 350 mL). The combined organic fractions were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude product was chromatographed using 30 % EtOAc/Hex with 0.5 % TEA to obtain the azide acetal (20) as a colorless oil, 33.65 g (50%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.72 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (dd, J = 1.4, 12.5 Hz, 2H), 4.05 – 3.98 (m, 2H), 3.33 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 6H), 3.01 (s, 1H), 1.99 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 100.90, 99.96, 69.59, 53.38, 53.13, 38.19; IR (neat film) 2950, 2107, 1409, 1123; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C8H15N3O4 (M + Na) 240.0960, found 240.0953.

(E)-ethyl 4-((2s,5s)-5-azido-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-2-methylbut-2-enoate (22)

Dioxane 20 (33.65g, 155 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (1 L) with water (6.25 mL, 347 mmol) and cooled to 0 °C. TFA (250 mL, 3.37 mol) was added to the reaction mixture to give 20% TFA/CHCl3 which was stirred at 0 °C for 40 min. The reaction was quenched with solid NaHCO3 (400 g, 4.76 mol) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered and concentrated. The resulting aldehyde 21 was used in the next step without further purification, and contained 20 % of the starting material 20 based on 1H NMR. Data for 21: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.79 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (dd, J = 12.6, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 4.06 (dd, J = 12.6, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 3.05 (s, 1H), 2.76 (dd, J = 4.7, 2.0 Hz, 2H).

(Carbethoxyethyldiene)triphenylphosphorane (51.15 g, 141 mmol) was added to a solution of this crude aldehyde 21 (26.59 g, 155 mmol) dissolved in benzene (333 mL) in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 2 hrs. A TLC was taken in 20 % EtOAc/Hex. The reaction mixture was concentrated and the crude product was chromatographed using 20 % EtOAc/Hex with 0.5 % TEA to give 22 with 20 as an oil, 28.61 g. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.78 (td, J = 7.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dd, J = 12.5, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 4.18 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.07 – 3.99 (m, 2H), 2.99 (s, 1H), 2.56 (ddd, J = 7.1, 5.2, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 1.84 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.80, 134.53, 130.54, 101.12, 69.76, 60.58, 53.12, 34.44, 14.28, 12.71; IR (neat film) 2981, 2860, 2105, 1707, 1654, 1451, 1254, 885; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C11H17N3O4 (M + Na) 278.1117, found 278.1106.

(E)-4-((2s,5s)-5-azido-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-2-methylbut-2-en-1-ol

A solution of DIBAL-H (280 mL, 1M in hexanes, 280 mmol) was added drop-wise to a well stirred solution of ester 22 (28.61 g, 112 mmol) dissolved in DCM (500 mL) that had been pre-cooled to −78 °C in an acetone/dry ice bath for 1 h. After this time the reaction was quenched successively with MeOH (200 mL) at −78 °C and saturated aqueous potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate (200 mL). The reaction mixture was then filtered and extracted with DCM. The combined organic fractions were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. The crude product was chromatographed using 30 % EtOAc/Hex to give 17.32 g (52 %, in three steps) of pure alcohol along with 4g, (12%) of 20. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.50 (s, 1H), 4.67 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 2H), 4.05 – 3.99 (m, 4H), 2.96 (s, 1H), 2.49 – 2.41 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.46 (bs, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.97, 118.29, 102.03, 69.82, 68.56, 53.20, 33.36, 13.94; IR (neat film) 3397, 2917, 2861, 2107, 1393, 1289, 1243, 1142, 1043, 1007; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C9H15N3O3 (M + Na) 236.1011, found 236.1004.

2-((E)-4-((2s,5s)-5-azido-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-2-methylbut-2-enylthio)benzo[d]thia zole

A solution of 2-mecaptobenzothiazole (16.1 g, 97 mmol) and Ph3P (24.3 g, 93 mmol) in anhyd THF (350 mL) was stirred at 0 °C as DIAD (20.2 mL, 97 mmol) in toluene (40 mL) was added slowly over 30 min. The resulting yellow suspension was allowed to stir for 15 min as the alcohol from above (17.2 g, 81 mmol) in anhyd THF (80 mL) was added drop-wise over 20 min. The resulting yellow suspension was allowed to stir for 30 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was then diluted with hexane (200 mL) and ethyl acetate (200 mL), the resulting solids were filtered and washed with ethyl acetate (100 mL). This mixture was concentrated then diluted with ethyl acetate (400 mL) and washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (100 mL) and water (100 mL), then dried over Na2SO4. This solution was concentrated and purified by flash chromatography (30% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 25 g (84%) of the sulfide as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 8.0, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 – 7.37 (m, 1H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 1H), 5.62 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (s, 2H), 3.93 (dd, J = 12.4 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 1H), 2.48 – 2.37 (m, 2H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.84, 153.22, 135.42, 132.62, 126.00, 124.22, 123.40, 121.62, 120.92, 101.87, 69.64, 53.25, 42.96, 33.97, 15.60; IR (Neat Film) 2975, 2917, 2856, 2104, 1457, 1426, 1291, 1239, 1140, 1044, 1004 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C16H19N4O2S2 (M+1)+ 363.0949, found 363.0942.

2-((E)-4-((2s,5s)-5-azido-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-2-methylbut-2-enylsulfonyl)benzo[d ]thiazole (23)

A solution of sulfide derivative from above (0.3 g, 0.82 mmol) in EtOH (6 mL) was treated with a mixture of ammonium molybdate·4H2O (0.2 g, 0.16 mmol) and 30% H2O2 (1 mL, 8.28 mmol) and the pH was adjusted to 4–5 with 7.0 buffer. This solution was allowed to stir for 4h at room temperature then diluted with water (15 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (2×20 mL), the combined organic phase was washed with brine (25 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (40–65% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 23 (254 mg, 78%) as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.29 – 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.05 – 7.98 (m, 1H), 7.68 – 7.55 (m, 2H), 5.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 4.03 – 3.95 (m, 2H), 3.77 – 3.68 (m, 2H), 2.84 (s, 1H), 2.36 – 2.28 (m, 2H), 1.86 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.57, 152.78, 137.02, 130.65, 127.90, 127.57, 125.60, 125.03, 122.29, 101.14, 69.48, 64.41, 53.01, 34.05, 17.12; IR (Neat Film) 2974, 2922, 2857, 2105, 1471, 1422, 1327, 1291, 1239, 1136, 1021 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C16H19N4O4S2 (M+1)+ 395.0848, found 395.0848.

(3R,7S)-7-((1E,3E)-5-((2s,5R)-5-azido-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-3-methylpenta-1,3-die nyl)-5,5-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octane (25)

A solution of the sulfone derivative 23 (215 mg, 0.55mmol) in anhyd THF (8 mL) was allowed to stir at −78 °C while a solution of lithium bis(trimethylsilyl) amide (0.62 mL, 0.64 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was added dropwise. After stirring for 30 min at −78 °C, aldehyde 2415 (93 mg, 0.54 mmol) in anhyd THF (5 mL) was added by drop-wise via syringe. The resulting suspension was stirred at −78 °C for 1.5 h and allowed to warm to room temperature and stir for 12 h. The reaction was then poured into a saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (10 mL) and the product was extracted with ethyl acetate (3× 25 mL). The combined extracts were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent and purification by flash chromatography (20% ethyl acetate in hexane) gave 70 mg (37%) of diene 25 (88:12 E : Z) as a viscous liquid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.27 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 5.60 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.62 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (ddd, J = 11.1, 6.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.27 – 4.19 (m, 2H), 4.00 (dd, J = 12.4, 2.1 Hz, 2H), 2.98 (s, 1H), 2.59 – 2.55 (m, 2H), 2.54 – 2.49 (m, 2H), 2.04 – 1.85 (m, 2H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.25 – 1.11 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 135.75, 135.68, 127.95, 125.51, 102.09, 73.03, 69.72, 69.49, 55.68, 53.30, 51.06, 42.46, 38.57, 34.08, 31.54, 23.77, 12.61; IR (Neat Film) 2974, 2915, 2861, 2105, 1447, 1328, 1289, 1141, 1045 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C18H28N33O4 (M+1)+ 350.2080, found 350.2067.

(S,Z)-4-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-N-((2R,5R)-2-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-di methyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octan-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)pent -2-enamide

A solution of the azide derivative 25 (2 g, 5.72 mmol) in benzene (40 mL) at room temperature under N2 was allowed to stir as Ph3P (4.50 g, 17.17 mmol) was added. The resulting solution was then heated at 45 °C for 2.5 h, by which time LC/MS showed that the starting material has been consumed. Water (1 mL) was added and the reaction was heated at 45 °C for an additional 2h, by which time LC/MS indicated that the formation of free amine was complete. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with CH2Cl2 (100 mL) and ether (20 mL), and then dried over Na2SO4. This mixture was then filtered and concentrated. The residue was dissolved in anhyd acetonitrile (6 mL) and used in the next step without further purification.

A stirred solution of (S,Z)-4-(TBSO)pent-2-enoic acid40 (2.6 g, 11.44 mmol) in anhyd CH3CN (30 mL) at 0 °C was treated with HBTU (4.1 g, 10.87) and diisopropyl ethylamine (6.12 mL, 34.3 mmol) sequentially. The above reaction solution was added to a solution containing the amine from above in CH3CN (30 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting solution was the stirred for another 2 h at room temperature at which time LC/MC showed the formation of product and disappearance of all of the starting material. Saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (70 mL) and ethyl acetate (400 mL) were added. The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2×100 mL) and washed with brine (100 mL). Evaporation and purification of the crude by flash chromatography (25% ethyl acetate in hexane) gave 2.1 g (69%) of the title compound as a liquid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.41 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.28 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 12H), 6.06 (dd, J = 11.6, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.64-5.52 (m, 2H), 5.48 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.51 – 4.42 (m, 1H), 3.98-3.92 (m, 5H), 2.59-2.55 (m, 2H), 2.50-2.46 (m, 2H), 2.04 – 1.86 (m, 2H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.29 – 1.24 (m, 6H), 1.23 – 1.14 (m, 2H), 0.88 (s, 9H), 0.05 (s, 3H), 0.04 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.98, 151.41, 135.75, 135.55, 128.11, 125.41, 119.06, 102.29, 73.07, 70.44, 70.32, 69.46, 65.43, 55.66, 51.06, 43.52, 42.46, 38.59, 34.17, 31.54, 25.90, 23.78, 18.20, 12.65, −4.68, −4.74; IR (Neat Film) 3332, 2955, 2930, 2857, 1758, 1715, 1665, 1526, 1471, 1373, 1254, 1117, 1077, 1003 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C29H50NO6Si (M+1)+ 536.3407, found 536.3397.

(S,Z)-N-((2R,5R)-2-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)-4-hydroxypent-2-enamide

A solution of TBS protected amide from above (2.1 g, 3.92 mmol) in 20 mL of THF at −10 °C as TBAF (5.4 mL, 5.49 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was added. The light yellow solution was allowed to stir for 1.5 h at 0 °C and allowed to stir at room temperature for 2h by which time TLC and LC/MS showed the starting material has been consumed. THF was evaporated and diluted with CHCl3 (100 mL) and water (20 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (30 mL). The CHCl3 layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 75 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. Concentrated and the residue was purified by Prep-SFC (OD-H column, 10% MeOH) to give 780 mg (47%) of the title alcohol as a liquid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.67 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.28 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (dd, J = 11.9, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (dd, J = 12.0, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (s, 1H), 4.80 (s, 1H), 4.60 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (ddd, J = 10.9, 6.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.02 – 3.90 (m, 5H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.53 – 2.44 (m, 2H), 2.02 – 1.85 (m, 2H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.35 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H), 1.23 – 1.13 (m, 2H), 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.89, 150.80, 135.82, 135.52, 128.17, 125.28, 122.49, 102.34, 73.08, 70.13, 69.46, 64.48, 55.66, 51.06, 43.87, 42.44, 38.58, 34.11, 31.53, 23.77, 22.67, 12.66; IR (Neat Film) 3322, 2973, 2912, 2856, 1656, 1627, 1526, 1451, 1377, 1254, 1117, 1077, 1003 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C23H36NO6 (M+1)+ 422.2543, found 422.2534.

(S,Z)-5-((2R,5R)-2-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octa n-5-yl)-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-ylamino)-5-oxopent-3-en-2-yl isobutyrate (26)

A solution of alcohol from above (690 mg, 1.63 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (14 mL) at 0 °C as Et3N (8.18 mmol, 1.1 mL) and DMAP (30 mg, 0.246 mmol) were sequentially added. After 5 min, isobutyric anhydride (0.9 mL, 5.40 mmol) was added. The solution was allowed to stir for 1h at the same temp by which time TLC indicated that starting material has completely been consumed. The reaction mixture was diluted with water (10 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×50 mL). The organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine, and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by flash column (40–50% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 770 mg (96%) of 26 as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.16 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 6.10 – 5.99 (m, 1H), 5.81-5.72 (m, 2H), 5.53 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.45 – 4.33 (m, 1H), 3.97 – 3.80 (m, 5H), 2.50 (s, 2H), 2.49 – 2.39 (m, 3H), 1.97 – 1.74 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.31 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.17 – 1.07 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.71, 164.82, 142.32, 135.64, 135.62, 127.99, 125.65, 123.25, 102.19, 73.05, 70.23, 70.20, 69.47, 68.55, 55.66, 51.06, 43.73, 42.46, 38.59, 34.16, 34.02, 31.54, 23.77, 20.04, 18.98, 18.90, 12.63; IR (Neat Film) 3332, 2974, 2936, 2871, 1730, 1669, 1638, 1525, 1415, 1373, 1266, 1195, 1130 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z Calcd for C27H42NO7 (M+1)+ 492.2961, found 492.2949.

N-((2s,5R)-2-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octan-5-yl) -3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)acetamide (27)

(2s,5R)-2-((2E,4E)-5-((3R,5S)-7,7-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[2.5]octan-5-yl )-3-methylpenta-2,4-dienyl)-1,3-dioxan-5-amine (9 mg, 0.029 mmol) which had been dried azeotrpically in CH3CN was dissolved in DCM (1.8 mL). DIPEA (51 µL, 0.294 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture followed by Ac2O (14 µL, 0.147 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temp for 28 hrs. The reaction mixture was concentrated and chromatographed using 5 % MeOH/CHCl3 to give 1.2 mg (12 %) of acetamide 27 as a viscous liquid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.39 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.28 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (dd, J = 15.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.51 – 4.42 (m, 1H), 3.99 – 3.87 (m, 5H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.52 – 2.45 (m, 2H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.99 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (dd, J = 13.7, 11.7 Hz, 1H), 1.75 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.24 – 1.18 (m, 1H), 1.16 (dd, J = 13.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.25, 136.41, 136.20, 128.77, 126.03, 102.93, 73.72, 71.05, 70.12, 56.31, 51.71, 44.40, 43.10, 39.24, 34.82, 32.18, 24.42, 24.12, 13.31; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H32NO5 (M + 1)+ 366.2280, found 366.2284.

Biology Experimental Section

Cell Culture

The cancer cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) or the DSMZ (Brunswick, Germany) and were maintained in growth media as recommended by the vendor. The PrEC normal prostate epithelial cells were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and maintained in prostate epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza). Human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were grown under standard culture conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified environment.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

Cell viabilities were determined by measuring the cleavage of the tetrazolium salt XTT to a water-soluble orange formazan by mitochondrial dehydrogenase, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, cell lines were seeded at various densities depending on the cell type. The adherent cell lines were allowed to adhere overnight before spliceosome modulator compound addition, whereas suspension cell lines were seeded the day of compound addition. Stock concentrations of the compounds were made in DMSO, diluted in culture media, and subsequently added to the plates at various final concentrations, then incubated for 72 hours. After the incubation period, the XTT labeling reagent, containing the electron-coupling reagent, was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours. The absorbance of each well was then determined at 490 nm with a reference wavelength of 690 nm using a VersaMax™ microplate reader (Sunnyvale, CA). The data are expressed as the percentage of growth compared to vehicle-treated cells, as calculated from absorbance and corrected for background absorbance. The IC50 is defined as the drug concentration that inhibits growth to 50% of the vehicle-treated control; IC50 values were calculated from sigmoidal analysis of the dose response curves using Origin v7.5 software (Northampton, MA).

In Vivo Tumor Growth Inhibition

JeKo-1 tumors were transplanted to female NOD/SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) on day 1 and, beginning on day 4, the mice (4 per group) received IV injections of vehicle (3.0% DMSO and 6.5% Tween 80 in 5% glucose solution), 5, 10, 25 or 50 mg/kg of compound 5 daily for five consecutive days. Tumor volume and mouse weights were measured three times a week. Tumor volumes were determined based on the following equation: (length × width2)/2.

Dual-Reporter Cell-based Splicing Assay

293T cells were transiently transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science), as described by the manufacturer, with the pTN24 dual-reporter splicing construct (gracious gift from Dr. Talat Nasim, Guy's Hospital, London, UK) for 48 hours and subsequently treated with or without spliceosome modulator compounds for 5 hours.37, 38 The degree of cell death was negligible at this time (data not shown). The cells were lysed and equal amounts of protein for each compound concentration were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity using the Dual-Light® Assay System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each entire assay was conducted in a single 96-well plate. The pTN24 dual-reporter construct contains β-galactosidase and luciferase coding sequences separated by an intronic linker containing a stop codon.37, 38 In the presence of splicing, the intronic sequence containing the stop codon is removed and both β-galactosidase and luciferase are expressed; if splicing is inhibited, the intron remains and only β-galactosidase is expressed. Assay data are expressed as the relative ratio of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity compared to control vehicle-treated samples.

In Vitro Splicing Assay

In vitro splicing reactions were performed as previously described.38 Briefly, standard reactions contained HeLa nuclear extract (Promega, Madison, WI), 13% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol, 33P-labeled β-globin pre-mRNA substrate, 80 mM MgCl2, 12.5 mM ATP/0.5 M creatine phosphate, and Dignam’s buffer D.39 Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 1 hour with or without spliceosome modulator compound, then terminated and the RNA products analyzed by autoradiography following electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide TBE-urea gel.

Immunofluorescence analysis

HeLa cells were grown on glass coverslips for 24 hours, fixed with cold methanol at −20°C for 10 min, and rinsed with PBS prior to incubation with SC35 (Sigma) or SF3B1 (SAP155, MBL International) primary antibodies (1/100 dilution with PBS) for 1 h at 37 °C in PBS. After washing with PBS the coverslips were incubated with an anti-mouse fluorescent secondary antibody (1/200 dilution) labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) as described above, washed, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and viewed on an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Cool Snap digital camera using a 60X magnification objective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Developmental Therapeutics Program of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, for providing the 60 cell line in vitro anti-tumor screening data for compound 5. This work was supported by NCI Cancer Center Core grant CA21765 and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PD, pladienolide; EDC, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide); DIAD, diisopropyl azodicarboxylate; DIBAL H, diisobutylaluminium hydride; TBAF, tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

Supporting Information Available: The supporting information includes the procedures for the synthesis of compounds 8–11 and compounds 14–19, and Supplemental Figures S1–S3. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rymond B. Targeting the spliceosome. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3:533–535. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0907-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer A. The structure and function of proteins involved in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:367–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaida D, Motoyoshi H, Tashiro E, Nojima T, Hagiwara M, Ishigami K, Watanabe H, Kitahara T, Yoshida T, Nakajima H, Tani T, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:576–583. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotake Y, Sagane K, Owa T, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shimizu H, Uesugi M, Ishihama Y, Iwata M, Mizui Y. Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizui Y, Sakai T, Iwata M, Uenaka T, Okamoto K, Shimizu H, Yamori T, Yoshimatsu K, Asada M. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. III. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activities. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2004;57:188–196. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima H, Hori Y, Terano H, Okuhara M, Manda T, Matsumoto S, Shimomura K. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. II. Activities against experimental tumors in mice and mechanism of action. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1996;49:1204–1211. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakajima H, Sato B, Fujita T, Takase S, Terano H, Okuhara M. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1996;49:1196–1203. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakajima H, Takase S, Terano H, Tanaka H. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. III. Structures of FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1997;50:96–99. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert BJ, Sivaramakrishnan A, Naka T, Czaicki NL, Koide K. Total syntheses, fragmentation studies, and antitumor/antiproliferative activities of FR901464 and its low picomolar analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2648–2659. doi: 10.1021/ja067870m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motoyoshi H, Horigome M, Ishigami K, Yoshida T, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M, Watanabe H, Kitahara T. Structure-activity relationship for FR901464: a versatile method for the conversion and preparation of biologically active biotinylated probes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;68:2178–2182. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borriello A, Cucciolla V, Oliva A, Zappia V, Della Ragione F. p27Kip1 metabolism: a fascinating labyrinth. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1053–1061. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert BJ, Sivaramakrishnan A, Naka T, Koide K. Total synthesis of FR901464, an antitumor agent that regulates the transcription of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2792–2793. doi: 10.1021/ja058216u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson CF, Jamison TF, Jacobsen EN. FR901464: total synthesis, proof of structure, and evaluation of synthetic analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9974–9983. doi: 10.1021/ja016615t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motoyoshi H, Horigome M, Watanabe H, Kitahara T. Total synthesis of FR901464: second generation. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1378–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagisetti C, Pourpak A, Jiang Q, Cui X, Goronga T, Morris SW, Webb TR. Antitumor compounds based on a natural product consensus pharmacophore. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:6220–6224. doi: 10.1021/jm8006195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rantanen VV, Denessiouk KA, Gyllenberg M, Koski T, Johnson MS. A fragment library based on Gaussian mixtures predicting favorable molecular interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:197–214. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohm M, Stűrzebecher J, Klebe G. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship analyses using comparative molecular field analysis and comparative molecular similarity indices analysis to elucidate selectivity differences of inhibitors binding to trypsin, thrombin, and factor Xa. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:458–477. doi: 10.1021/jm981062r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matter H, Schwab W, Barbier D, Billen G, Haase B, Neises B, Schudok M, Thorwart W, Schreuder H, Brachvogel V, Lonze P, Weithmann KU. Quantitative structure-activity relationship of human neutrophil collagenase (MMP-8) inhibitors using comparative molecular field analysis and X-ray structure analysis. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:1908–1920. doi: 10.1021/jm980631s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson CF, Jamison TF, Jacobsen EN. Total Synthesis of FR901464. Convergent Assembly of Chiral Components Prepared by Asymmetric Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10482–10483. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horigome M, Motoyoshi H, Watanabe H, Kitahara T. A synthesis of FR901464. Tet. Lett. 2001;42:8207–8210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert BJ, Koide K. Synthesis of a C4-epi-C1-C6 fragment of FR901464 using a novel bromolactolization. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3655–3658. doi: 10.1021/ol049160w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koide K, Albert BJ. Total syntheses of FR901464. Yuki Gosei Kagaku Kyokaishi. 2007;65:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchwald P, Bodor N. Physicochemical aspects of the enzymatic hydrolysis of carboxylic esters. Pharmazie. 2002;57:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaumont K, Webster R, Gardner I, Dack K. Design of ester prodrugs to enhance oral absorption of poorly permeable compounds: challenges to the discovery scientist. Curr. Drug Metab. 2003;4:461–485. doi: 10.2174/1389200033489253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morikawa M, Inoue M, Tsuboi M. Substrate specificity of carboxylesterase (E.C.3.1.1.1) from several animals. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1976;24:1661–1664. doi: 10.1248/cpb.24.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaccaro HA, Zhao Z, Clader JW, Song L, Terracina G, Zhang L, Pissarnitski DA. Solution-Phase Parallel Synthesis of Carbamates as gamma-Secretase Inhibitors. J. Comb. Chem. 2008;10:56–62. doi: 10.1021/cc700100r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For more information on the NCI-60 cell-line panel see: http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/br anches/btb/ivclsp.html.

- 28.Park JR, Eggert A, Caron H. Neuroblastoma: biology, prognosis, and treatment. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2008;55:97–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strother D. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors of childhood: diagnosis, treatment and challenges. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:907–915. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourdeaut F, Freneaux P, Thuille B, Bergeron C, Laurence V, Brugieres L, Verite C, Michon J, Delattre O, Orbach D. Extra-renal non-cerebral rhabdoid tumours. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2008;51:363–368. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bissery MC, Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Lavelle F. Experimental antitumor activity of taxotere (RP 56976, NSC 628503), a taxol analogue. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4845–4852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu K, Bi L, Zhao M, Wang C, Dolan C, Kao MC, Tok JB, Peng S. Stereoselective synthesis and anti-inflammatory activities of 6- and 7-membered dioxacycloalkanes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goddard-Borger ED, Stick RV. An efficient, inexpensive, and shelf-stable diazotransfer reagent: imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide hydrochloride. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3797–3800. doi: 10.1021/ol701581g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]