Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) exist in three different forms, alpha (α), beta/delta (β/δ), or gamma (γ), all of which are expressed in skeletal muscle and play a critical role in the regulation of oxidative metabolism. The purpose of this investigation was to determine the mRNA expression pattern of the different PPARs and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) in muscles that largely rely on either glycolytic (plantaris) or oxidative (soleus) metabolism. Further, we also examined the alterations in the PPARs mRNA expression after one bout of endurance exercise or after 12 weeks of exercise training in the different muscles. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (5–8 months) were either run on the treadmill once or exercised trained for 12 weeks. The muscles were removed 24 h after the last bout of exercise. The results demonstrated with the exception of PPAR β/δ, the PPAR mRNAs are expressed to a greater extent in the soleus muscle than in the plantaris muscle in sedentary animals. PPARγ was the least abundantly expressed PPAR in either the soleus or the plantaris muscle. With respect to exercise training, only PPARγ mRNA expression increased in the soleus muscle, while PPARβ/δ and γ mRNA levels increased in the plantaris muscle. Minimal changes were detected in any of the PPARs with one bout of exercise training. These results suggest that PPARγ mRNA levels are the lowest in skeletal muscle among all of the PPARs and PPARγ mRNA is the most responsive to changes in physical activity levels.

Keywords: Muscle, Exercise, Training, mRNA

Introduction

The regulation of metabolic function in skeletal muscle has been an intense area of scientific research for numerous years. Skeletal muscle as a tissue is metabolically plastic in that changes in contractile activation of the tissue can affect metabolic mRNA and protein expression. In fact, in 1967 John Holloszy demonstrated that exercise training can have significant effects on mitochondrial enzyme activity in skeletal muscle [1]. Since, numerous studies have found that exercise-induced metabolic adaptations in muscle are highly specific to the type of exercise as well as its frequency, intensity, and duration [2]. Currently, numerous labs are attempting to identify the molecular mechanisms that regulate the metabolic phenotype of the muscle. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) have recently garnered a lot of attention based on their ability to affect gene expression of a number of genes involved in metabolic function.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand-activated transcription factors and members of the nuclear hormone receptor family [3]. The PPARs form homodimers or heterodimers with other PPARs or co-factors allowing them to bind with the consensus sequence AG GTCANAGGTCA. Currently, there are three different isoforms of PPARs, PPARα, PPAR β/δ, and PPARγ and the expression levels of the PPAR isoforms are dependent upon the tissue of interest [3]. PPARγ also has splice isoforms, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, with PPARγ2 being specifically contained in adipocytes [4]. Although, it has been suggested that skeletal muscle contains both γ isoforms this appears to be due to adipocyte contamination in skeletal muscle [4]. In particular, PPARs are thought to be expressed in tissue that are highly oxidative and transcriptionally target genes responsible for lipid metabolism [3].

Another molecular target, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha (PGC-1α), is a transcriptional co-regulator that can affect the metabolic function of skeletal muscle by increasing the expression of genes associated with the mitochondria [5]. Previous research has found that acute bouts of exercise can increase PGC-1α expression [3] and transgenic overexpression of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle results in a muscle that can oxidize lipid more effectively [5]. Thus, the PPARs and their co-factors have a unique ability to affect various phenotypic aspects of skeletal muscle.

The purpose of this investigation is to determine the expression pattern of the corresponding mRNAs for PPARα, PPAR β/δ, and PPARγ1 (referred to as PPARγ from now on) expression in skeletal muscles that are predominantly composed of oxidative (soleus) and glycolytic (plantaris) fibers. In addition, we also examine the effect of acute exercise and endurance exercise training on the mRNA expression of PPARα, PPAR β/δ, and PPARγ in both the soleus and the plantaris muscles. It was hypothesized that based on previous findings in the literature, PPARα, PPAR β/δ, and PPARγ mRNA expression will be associated with the oxidative potential of the muscle and the mRNA expression will be altered by an intervention that induces a more oxidative phenotype.

Methods

Animal model and treadmill training

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (age 2–3 months) were randomly assigned to an exercise training (trained) group (n = 9) or a sedentary group (n = 10). All animals were housed in the same facility with a 12:12-h light–dark cycle, with food and water provided ad libitum. Animals were exercise trained according to previously described protocols [6, 7]. Animals were familiarized by placing them on a motorized treadmill (0% grade) for a total of 5 days and running them at 15 m min−1 per day for 5 min (1st day) to 20 min (5th day) per day. For the acute exercise, rats ran for 1 day at 15, 30, and 15 m min−1 for 10, 40, and 10 min, respectively. For the trained group, the animals ran for 12 weeks at this protocol. Animals in the sedentary group were placed on the non-moving treadmill for the same amount of time as the trained rats to serve as handling controls. The soleus and plantaris muscles were not removed until 24 h after the last exercise bout with the exception for the acute bout, which was removed immediately after the exercise bout. This design allows us to determine effects of exercise training versus the effects of the acute bout of exercise. The animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (35 mg/kg; ip injection). The soleus and plantaris muscles were carefully dissected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The muscles were then stored at −80°C until needed. The study was conducted under the guidelines accepted by the American Physiological Society and received prior approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Citrate synthase activity

Citrate synthase activity was measured according to previously described methods [8] and normalized to the protein content of the sample.

Reverse transcription of total RNA

Total RNA was isolated and reversed transcribed according to previously described methodology [9]. Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was reversed transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA), mixed oligo (dT), random decamers (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) in a 25-μl reaction at 42°C for 50 min. The reaction was inactivated by incubation at 70°C for 15 min. The samples were subsequently stored at 4°C for later use.

Semi-quantitative PCR

All methods have been previously described [9, 10]. The following primer sequences were utilized (5′ → 3′): PPARγ forward = ccctggcaaagcatttgtat, PPARγ reverse = actggcacccttgaaaaatg; PPARβ/δ forward = aacatccccaactt cagcag, PPARβ/δ reverse = tactgcgcaagaactcatgg; PPARα forward = tcacacaatgcaatccgttt, PPARα reverse = ggccttgaccttgttcatgt, PGC-1α forward = atgtgtcgccttcttgctct, PGC-1α reverse = atctactgcctggggacctt, UCP3 forward = gagtcaggggactgtggaaa, UCP3 reverse = gcgttcatgtatcgggtctt, PDK4 forward = tcacacaatgcaatccgttt, and PDK4 reverse = caccagtcatcagcctcaga. All primers were purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA, USA).

Two microliters of each reverse transcription reaction were mixed with 12.5 μl of AccuPrime Super Mix II (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA), 0.5 μM 18S primer/competimer mix, and 0.2 μM target primer mix in final 25-μl volume. PPAR and PGC-1α amplifications were performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler with an initial denaturing step of 94°C for 2 min, followed by an optimized number cycles for each target for the following program 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C. The final cycle ended with 10 min at 72°C. The optimized number of cycles was as follows for each target: PPARγ = 35, PPARα = 30, PPARβ/δ = 29, PGC-1α = 35, UCP3 = 30, and PDK4 = 30. The signal determined for each target was subsequently normalized to the signal for the 18S target as previously described [9, 10]. For the experiments run comparing the two different muscle types (i.e., Fig. 1), all mRNA targets in both muscles were run simultaneously on the same PCR machine to ensure none of the differences detected were due to differences in amplification efficiency. This allowed us to accurately compare the expression levels of the different transcripts against each other and across both types of muscles. For the sedentary and exercise (acute and trained) conditions, each mRNA target was run individually in both types of muscle and in all three conditions, thus the different mRNA targets were analyzed separately.

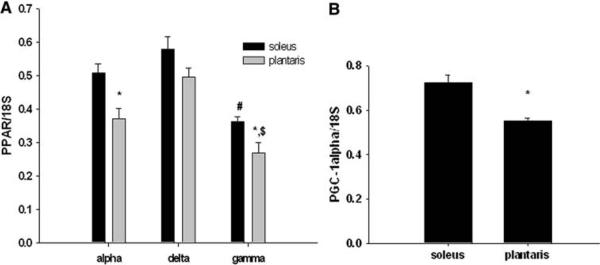

Fig. 1.

a, b PPARγ mRNA expression is relatively lower than PPARα and PPARβ/δ in both the soleus and plantaris muscles of the rat (a). PGC-1α mRNA expression is higher in the soleus muscle compared to the plantaris muscle (b).

* Significantly different than the soleus muscle, # different than soleus muscle in the alpha and delta group, $ different than the plantaris in the alpha and delta group (P < 0.05). n = 5 per group

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons followed by a Tukey's post hoc test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The coefficient of variation (CV) was checked for all targets in each group, with the largest CV being 3.2%.

Results

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor mRNA expression was compared across two phenotypically distinct skeletal muscles, the soleus, and plantaris muscles. The soleus muscle exhibits a high oxidative phenotype, while the plantaris muscle exhibits a more glycolytic phenotype [11]. Here, we found that with exception of PPARβ/δ, the soleus exhibited significantly higher levels of PPARα and PPARγ mRNA compared to the plantaris muscle (Fig. 1a). In addition, out of the three forms of PPAR, we found that PPARγ mRNA expression was the lowest in both the soleus and the plantaris muscle (Fig. 1a). No differences were detected in mRNA levels between PPARβ/δ and PPARα in the soleus or the plantaris muscles. PGC-1α mRNA expression was higher in the soleus muscle compared to the plantaris muscle (Fig. 1b).

Next, we sought to determine the effect of one bout of acute exercise and 12 weeks of exercise training on the expression of the three forms of PPARs and PGC-1α at the mRNA level in the soleus and plantaris muscles. In order to determine the effectiveness of the exercise conditions, we measured citrate synthase activity in the muscles. Citrate synthase activity significantly increased by ~57% after 12 weeks of exercise training in the plantaris muscles compared to the sedentary or one bout group (data not shown). No changes in citrate synthase activity were detected in the soleus muscle after the acute or the exercise training bouts (data not shown). There was a small significant decrease in the body weight after one bout of exercise, but no changes with the exercise training (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weights of all groups

| Sedentary | Acute exercise (one bout) | Trained | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 278 ± 4.39 | 257 ± 9.07* | 273 ± 7.92 |

Statistically different than all groups (P < 0.05)

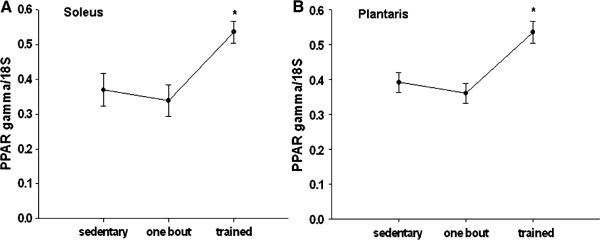

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-γ mRNA expression significantly increased in the exercise trained group compared to the sedentary group in both the soleus and plantaris by 45 and 37%, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). No changes were detected in PPARcγ mRNA expression after one bout of exercise in either the soleus or the plantaris muscles.

Fig. 2.

a, b PPARγ mRNA is increased in the plantaris (b) and soleus muscle (a) after 12 weeks of treadmill training compared to the sedentary animals. * Significantly different than the sedentary group (P < 0.05). n = 5 sedentary, n = 7 one bout, n = 8 trained

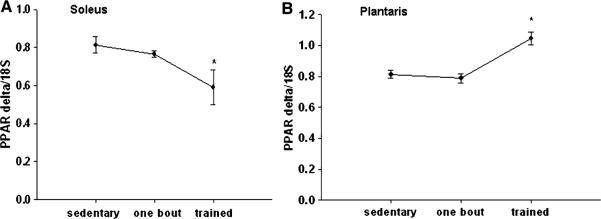

Compared to sedentary group, PPARβ/δ mRNA expression significantly increased in the plantaris muscle after the exercise training by 28%, but in the soleus the expression actually significantly decreased by 27% (Fig. 3a, b). No changes were detected in PPARβ/δ mRNA expression after one bout of exercise in either the soleus or the plantaris muscles.

Fig. 3.

a, b PPARβ/δ mRNA is increased in the plantaris (b), but decreased in the soleus muscle (a) after 12 weeks of treadmill training compared to the sedentary animals.

* Significantly different than the sedentary group (P < 0.05). n = 5 sedentary, n = 7 one bout, n = 8 trained

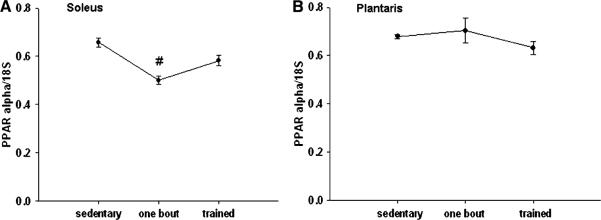

No major changes were detected in PPARα mRNA expression with exercise training in either muscle compared to the sedentary group; however, there was a small significant decrease after one bout of exercise in PPARα in the soleus muscle (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

a, b PPARα mRNA is decreased in the soleus muscle (a) after one bout of exercise, but does not changes in the plantaris muscle (b).

# Significant differently than the sedentary group (P < 0.05). n = 5 sedentary, n = 7 one bout, n = 8 trained

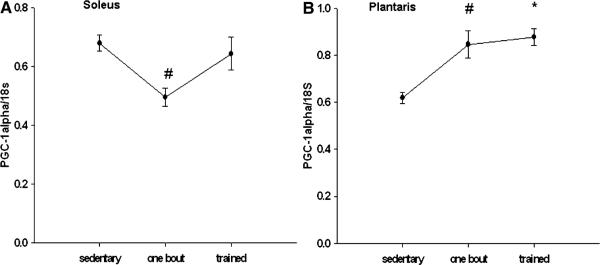

In the plantaris muscle, compared to the sedentary group significant increases of 37 and 42% in PGC-1α mRNA were detected in the plantaris muscle after one bout and with exercise training, respectively (Fig. 5a, b). In the soleus muscle, there was a small, but significant decrease in PGC-1α mRNA expression after one bout of exercise, but no differences in the exercise trained group when compared to the sedentary group.

Fig. 5.

PGC-1α mRNA is increased in the plantaris after one bout and with training, compared to the sedentary animals. *, # Significantly different than the sedentary group (P < 0.05). n = 5 sedentary, n = 7 one bout, n = 8 trained

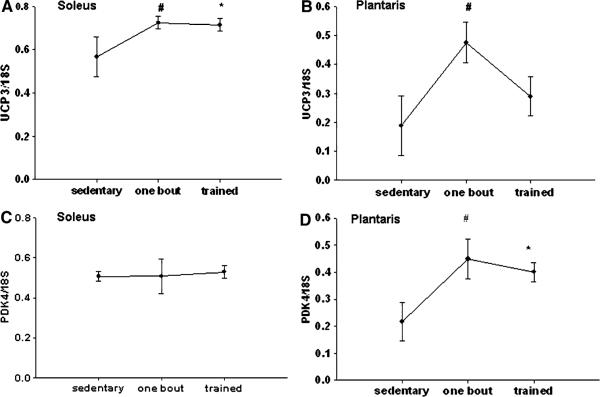

UCP3 and PDK4 have been implicated as downstream targets for the PPAR family of transcription factor, since both contain PPAR consensus elements in their respective promoters. In the plantaris muscle, there was a significant increase in UCP3 and PDK4 mRNA expression after one bout and with exercise training compared to the sedentary group (Fig. 6b, d). However, in the soleus there were no significant changes in PDK4 expression compared to the sedentary group, while there was a significant increase in UCP3 expression after one bout of exercise, but not with training (Fig. 6a, c).

Fig. 6.

a–d UCP3 (a, b) and PDK4 (c, d) mRNA expression is increased in skeletal muscle with exercise training.

*, # Significantly different than the sedentary group (P < 0.05). n = 5 sedentary, n = 7 one bout, n = 8 trained

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate that PPARγ and PPARβ/δ mRNA levels are responsive to endurance exercise training in both the soleus and the plantaris muscles of the rat. In addition, it was also demonstrated that one bout of endurance exercise altered PPARα mRNA expression in the soleus/plantaris muscle and failed to significantly effect any of the other PPARs in skeletal muscle. Finally, the data also suggest that PPAR mRNA expression is typically higher in an oxidative muscle and lower in the glycolytic muscle, with PPARγ being expressed at the lowest level of the PPARs in muscle.

Surprisingly, very little has been done comparing changes in PPAR mRNA expression across different muscle types or in response to differing amounts of exercise training. In fact, we are unaware of any data set, which have compared all three. However, some have looked at changes in one or two of the PPARs. For example, repetitive muscular activation patterns of slow motor units increase PPARβ/δ expression in predominately glycolytic skeletal muscle [12]. We found that the soleus muscle exhibits higher expression levels of PPARβ/δ compared to the plantaris, which falls in line with the muscles oxidative profile. Based on gain-of-function experiments, the increased PPARβ/δ expression appears to contribute to an enhanced oxidative metabolic capacity of the muscle [12, 13]. This has led to increased speculation that PPARβ/δ may play a major role in regulation of oxidative or mitochondrial gene expression in skeletal muscle. Thus, it is enticing to suggest that exercise training-induced increases in PPARβ/δ expression in muscle that is predominately glycolytic contributes to the well-documented training-induced enhancement of oxidative metabolic properties of muscle.

Here, we found PPARγ expression increases in both the soleus and the plantaris muscle with exercise training. Increases in PPARγ expression have also been found in human quadriceps biopsies 3 h after a bout exercise, but not 48 h post-exercise [14]. These data are in line with our data, which were collected 24 h post-exercise after one bout or the last bout in the trained group. In contrast, Tunstall et al. found reductions in PPARγ expression in the quadriceps muscle biopsies with 9 days of exercise training [15]. These differences might be in part due to the differences in species or in the length of training duration between the two studies (i.e. 9 days vs. 12 weeks).

Our findings indicate that minimal changes occur in PPARα mRNA expression with either acute or long term exercise training. This agrees with data in collected in humans, which indicated that PPARα expression does not appear to change with exercise changing in the quadriceps muscle [16]. Interestingly, the loss of PPARα expression in mice resulted in significant reductions in exercise capacity, without significant alterations in metabolic capacity of the muscle, which was predicted to be the result compensatory increase in PPARβ/δ expression [17]. Thus, it would suggest that normal expression patterns of PPARα are critical for maintenance of exercise capacity; however, it may be found that PPARα alone is not critical for skeletal muscle, since the PPARs may have some redundant qualities.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are ligand activated transcription factors. At this time, only a few target genes have been identified as having PPAR consensus elements within their specific promoters, although a number of metabolic genes are known to change with overexpression of PPARβ/δ, at this time, it is unclear if that is due to direct activation by PPARβ/δ or secondary effects of the overexpression. Specifically, two genes that are expressed in muscle, UCP3 and PDK4, are both known have PPAR elements in their promoter, with PDK4 specifically responding to activation of PPAR delta, while UCP3 appears to have the ability to respond to any of the three forms of PPARs [18–20]. Our data indicate that PDK4 expression was higher in the soleus muscle than the plantaris (data not shown), which corresponds with the increased PPARβ/δ expression in the soleus muscle. In addition, PDK4 increased with exercise training in a similar fashion as PPARβ/δ as in the plantaris muscle. Surprisingly, UCP3 mRNA expression was significantly lower in the soleus muscle compared to the plantaris muscle at baseline (data not shown), although these data are confirmed by similar findings in human muscle in which UCP protein expression is much more abundant in IIX fibers compared to Type I fibers [21]. Finally, we found in the soleus muscle there are significant increases in UCP3 mRNA after one bout of exercise, but not with training. Conversely, in the plantaris muscle there are significant increases in UCP3 mRNA expression with training suggesting that PPARs may not contribute to UCP3 regulation at rest, may contribute to alterations in UCP3 expression changes with training in mixed or glycolytic fiber dominated muscles.

Interestingly, our data suggest that muscles that are phenotypically distinct (i.e., soleus vs. plantaris) show markedly different changes in PPAR mRNA expression to acute and repeated bouts of exercise. Since, the soleus muscle is already highly oxidative it is not terribly surprising that no increases in PPAR expression were detected with under any of the conditions. It is well-known that the soleus muscle has a high capacity based on its very high composition of oxidative fibers [11], thus it is possible that the soleus is not capable of increasing its oxidative capacity anymore in response to the exercise training bouts compared to the plantaris muscle. This is further confirmed by the fact that the repeated bouts of exercise training resulted in significant increases in citrate synthase activity in the plantaris muscle; however, we found no significant changes in citrate synthase activity in the soleus muscle. However, others have found changes in citrate synthase activity in the soleus muscle with treadmill training [22]. When you compare the training protocols, Siu et al. ran their rats for the last 3 weeks at 28 m/min for 55 min [22], while our rats ran at a similar speed for a shorter duration. Thus, their exercise protocol was longer in duration which potentially contributed to the detectable increases in citrate synthase activity in the soleus. If the major role of the PPARs is to regulate oxidative metabolism gene expression then it is possible that PPAR mRNA expression is sufficiently elevated in the soleus muscle to the point that it cannot increase anymore, while in a muscle that is maintains a more glycolytic phenotype there is an enhanced response to exercise training in the PPARs. Specifically, the PPARs are likely to have a profound effect on muscle with a low mitochondrial density (glycolytic, plantaris muscle) compared to muscle that retains a high mitochondrial density (oxidative, soleus muscle).

Unlike, the PPARs, quite a few investigations have shown that PGC-1α mRNA expression changes with acute and chronic exercise training (for review see [23]). Our findings confirm these data and extend them by suggesting that muscles that express a more glycolytic phenotype will see a robust response in expression levels to exercise training compared to muscles that are already oxidative to begin with prior to the exercise training. Overexpression of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle in mice results large increases in mitochondrial density, which is associated with in enhanced endurance capacity and a corresponding decreased RER [5]. Interestingly, not all investigations have shown changes in PGC-1α expression with exercise training in those humans no changes in PGC-1α mRNA were detected with acute exercise or short-term exercising training [15]. This may, in part, be due to the fact that biopsies were taken from the quadriceps muscle and thus it is difficult to account for fiber type differences between subjects. If coupled with our findings, it is possible that samples from the quadriceps were predominately oxidative fibers, which combined with our findings suggests that PGC-1α mRNA expression does not change drastically in muscle that maintains a more oxidative phenotype.

Overall our findings suggest that the mRNA of the PPAR family of transcription factors is sensitive to exercise training in skeletal muscle, but is not particularly sensitive acute bouts of endurance exercise. These findings would suggest that changes in the PPAR mRNA expression are most likely mediated by the accumulation of repeated bouts of exercise as opposed to single bouts of activity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Emily Pettycrew, Matt Lucero, and Christian Alvarez for their expert technical assistance. These experiments were supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants HL 40306-15 (RLM) and HL 72790-02 (RLM).

References

- 1.Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2278–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hood DA, Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, et al. Coordination of metabolic plasticity in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2265–2275. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muoio DM, Koves TR. Skeletal muscle adaptation to fatty acid depends on coordinated actions of the PPARs and PGC1 alpha: implications for metabolic disease. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:874–883. doi: 10.1139/H07-083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilde AJ, Van Bilsen M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARS): regulators of gene expression in heart and skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;178:425–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvo JA, Daniels TG, Wang X, et al. Muscle-specific expression of PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha improves exercise performance and increases peak oxygen uptake. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1304–1312. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01231.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DA, Lynch JM, Armstrong CJ, et al. Susceptibility of the heart to ischaemia-reperfusion injury and exercise-induced cardioprotection are sex-dependent in the rat. J Physiol. 2005;564:619–630. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spangenburg EE, Brown DA, Johnson MS, et al. Exercise increases SOCS-3 expression in rat skeletal muscle: potential relationship to IL-6 expression. J Physiol. 2006;572:839–848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srere P. Citrate synthase. Methods Enzymol. 1969;13:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spangenburg EE, Abraha T, Childs TE, et al. Skeletal muscle IGF-binding protein-3 and -5 expressions are age, muscle, and load dependent. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E340–E350. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00253.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spangenburg EE. SOCS-3 induces myoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10749–10758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong RB, Phelps RO. Muscle fiber type composition of the rat hindlimb. Am J Anat. 1984;171:259–272. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001710303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunde IG, Ekmark M, Rana ZA, et al. PPARdelta expression is influenced by muscle activity and induces slow muscle properties in adult rat muscles after somatic gene transfer. J Physiol. 2007;582:1277–1287. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, et al. Regulation of muscle fiber type and running endurance by PPARdelta. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahoney DJ, Parise G, Melov S, et al. Analysis of global mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle during recovery from endurance exercise. FASEB J. 2005;19:1498–1500. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3149fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tunstall RJ, Mehan KA, Wadley GD, et al. Exercise training increases lipid metabolism gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E66–E72. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00475.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helge JW, Bentley D, Schjerling P, et al. Four weeks oneleg training and high fat diet does not alter PPARalpha protein or mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;101:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muoio DM, MacLean PS, Lang DB, et al. Fatty acid homeostasis and induction of lipid regulatory genes in skeletal muscles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha knock-out mice. Evidence for compensatory regulation by PPAR delta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26089–26097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degenhardt T, Saramaki A, Malinen M, et al. Three members of the human pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family are direct targets of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villarroya F, Iglesias R, Giralt M. PPARs in the control of uncoupling proteins gene expression. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:74364. doi: 10.1155/2007/74364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riquet FB, Rodriguez M, Guigal N, et al. In vivo characterisation of the human UCP3 gene minimal promoter in mice tibialis anterior muscles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell AP, Wadley G, Hesselink MK, et al. UCP3 protein expression is lower in type I, IIa and IIx muscle fiber types of endurance-trained compared to untrained subjects. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445:563–569. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siu PM, Donley DA, Bryner RW, et al. Myogenin and oxidative enzyme gene expression levels are elevated in rat soleus muscles after endurance training. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:277–285. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00534.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Z, Li P, Akimoto T. Transcriptional control of the PGC-1alpha gene in skeletal muscle in vivo. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35:97–101. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3180a03169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]